Abstract

Purpose of review

Antipsychotics are frequently prescribed to women of childbearing age and are increasingly prescribed during pregnancy. A small, but growing, body of research on implications for pregnancy and infant outcomes is available to inform the risks and benefits of in utero exposure to antipsychotics. This review examines the existing published research on the use of common typical and atypical antipsychotics in pregnancy and the implications for pregnancy and infant outcomes.

Recent findings

The majority of studies do not show associations with major malformations and antipsychotic use in pregnancy, with the possible exception of risperidone. There is concern that atypical antipsychotics may be associated with gestational diabetes. Metabolic changes during pregnancy may necessitate dose adjustments.

Summary

In general, it is recommended that women who need to take an antipsychotic during pregnancy continue the antipsychotic that has been most effective for symptom remission. Further study on risperidone is needed to better understand its association with malformations, and it is not considered a first-line agent for use during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Antipsychotics are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis, and depression and are commonly used off-label for sleep and anxiety [1]. Compared with men, women are more likely to receive antipsychotic medications throughout the lifespan, with the highest prevalence of use during their childbearing years [2, 3]. Typical antipsychotics have commonly been prescribed during pregnancy for the treatment of psychiatric illnesses and off-label as antiemetics for hyperemesis. Typical antipsychotic use for any indication has significantly declined since the introduction of atypicals. During the past two decades, atypical antipsychotic use among pregnant women has more than doubled and 1.3% of pregnancies are exposed to atypical antipsychotics compared with 0.1% of pregnancies exposed to typicals [4, 5].

Discontinuation of antipsychotics during pregnancy increases the risk of bipolar and schizophrenia episode recurrence. Patients with schizophrenia who stop their antipsychotic medication have a 53% increased risk of symptom worsening over a 10-month period compared with a 16% relapse rate among patients who continue treatment [6]. The rate of bipolar episode recurrence in pregnancy is twice as high in patients who discontinue treatment compared with those who remain on medications [7]. Recurrence of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression episodes during pregnancy has been associated with adverse outcomes including an increased risk of placental abnormalities, small for gestational age fetuses, fetal distress, neonatal hypoglycemia, and the potential for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes [8]. Additionally, infants born to mothers with symptomatic schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are more likely to have preterm delivery [9,10,11], low birthweight [12], disordered attachment [13], and delayed development [14]. Women suffering from untreated mental illness are more likely to engage in behaviors that result in poor perinatal outcomes including impulsivity that leads to reckless behavior such as increased indiscriminate sex and exposure to sexually transmitted infections, smoking, increased alcohol and drug use, less prenatal care, and poor nutrition [15]. Furthermore, women with recurrence of mental illness in the perinatal period have increased risk for suicide, a leading cause of maternal death [16].

Antipsychotic treatment during pregnancy requires a risk-benefit analysis, and most often, the benefits of treatment are the justification for the risks of medication exposure. The investigation of whether newer atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of congenital malformations and poor pregnancy outcomes is ongoing. However, most data on atypical antipsychotics suggest these agents have low reproductive risk and the rate of congenital malformation is not higher than the baseline rate of 3-5% in the general population [17,18,19]. Consistent with the goals of the new FDA and Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule [20], clinicians must consider the risks of untreated illness as well as pharmacotherapy-related maternal adverse reactions, infant outcomes, and birth complications when counseling patients about medications in pregnancy and postpartum. Discussion of dosing requirements during gestation and any adverse effects related to breastfeeding must also be addressed. This article will review the available literature on perinatal outcomes and treatment considerations for atypical antipsychotics and commonly used typical antipsychotics including the following:

-

1.

Congenital malformations.

-

2.

Neonatal adaptation and infant neurodevelopment.

-

3.

Gestational diabetes.

-

4.

Metabolism and dosing during pregnancy.

-

5.

The risks for use during breastfeeding.

Risks of congenital malformations and pregnancy-related complications

Typical antipsychotics

Concerns of extrapyramidal symptoms associated with typical antipsychotics led to the development and introduction of atypical antipsychotics. As a class, typical antipsychotics have not been associated with congenital malformations. Huybrechts and colleagues completed a cohort study including 1.34 million pregnancies, 733 of which filled at least one prescription for a typical antipsychotic during the first trimester [21•]. The absolute risk for congenital malformations was higher among women treated with typical antipsychotics (38.2/1000 live births compared to 32.7/1000 in pregnancies not exposed to antipsychotics). Upon adjustment for confounding factors such as maternal age, diagnoses, and other medication exposures, congenital and cardiac malformations were not significantly associated with typical antipsychotic exposure. Investigators of two additional studies of infants exposed to typical antipsychotics in utero noted decreased gestational age and lower birth weights, but were confounded by concurrent smoking and illicit substance use [22, 23]. Because of their effectiveness and common use in women of childbearing age we review published data on the reproductive risks of typical agents, haloperidol and perphenazine.

Haloperidol

Haloperidol exposure in pregnancy has been studied in women who have taken it as an antipsychotic as well as an off-label antiemetic. Although there have been several case reports of limb defects after first-trimester exposure, larger studies have not demonstrated an increased risk for this birth defect [24,25,26]. Waes and Velde reviewed 92 cases of low-dose (1.2 mg/day) haloperidol exposure for hyperemesis gravidarum during the first trimester and found no cases of malformations [27]. Two recent reviews also did not find associations with haloperidol exposure and malformations. The Swedish Birth Register reported on 78 cases of haloperidol exposure of which 2 (2.6%) had malformations [28]. A study by Diav-Citrin and colleagues from the European Network of Teratogen Information Services followed 136 pregnancies exposed to haloperidol during first trimester and also found no increased risk of congenital malformation [29].

Haloperidol has been associated with an increased risk of adverse infant outcomes. Diav-Citrin et al. evaluated 188 pregnancies with oral or parenteral haloperidol exposure and determined that haloperidol exposure was associated with shorter gestational age and lower birth weight [29]. The gestational age at delivery was the biggest contributor to birth weight, but exposure to haloperidol and smoking status were also contributing factors. Lin et al. reviewed 242 pregnancies of mothers with schizophrenia, and of the 190 who received typical antipsychotic medications, most mothers received monotherapy with haloperidol (n = 33), flupentixol (n = 55), or sulpiride (n = 77). Women with schizophrenia who took antipsychotics during pregnancy had a higher odds of preterm birth (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 2.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.50–4.11) compared with women with schizophrenia and without exposure (n = 454). This finding, as noted by the authors, is preliminary and may be influenced by variables that were not controlled for including maternal smoking and substance use [30].

Haloperidol has not been associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or stillbirth [29].

Perphenazine

Perphenazine, used both as an antiemetic and as an antipsychotic, also has not been associated with congenital malformations. The Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP) studied 166 women taking perphenazine during pregnancy, 63 of whom took it during first trimester; no statistically significant difference in congenital malformations compared to women who were not exposed was found [31, 32]. In a retrospective review of the Swedish Medical Birth Register, Reis and Källén report on 90 pregnancies with early exposure to perphenazine, two (2.2%) of which had congenital malformations [28].

The CPP study also noted that mortality and birth weight did not differ significantly in the perphenazine exposed infants, and there was no significant difference in IQ of the offspring at 4 years of age [31].

Atypical antipsychotics

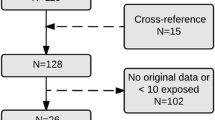

Atypical antipsychotics are commonly prescribed to perinatal women for both on- and off-label uses. We review the published data on malformations, infant outcomes, and pregnancy outcomes (Tables 1 and 2) of individual antipsychotics in the order of prevalence of use [5, 21•]. There are insufficient data to comment on the use of asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, or illoperidone during pregnancy or lactation.

Quetiapine

Quetiapine is the most prescribed atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy [5, 21•]. Huybrechts et al. determined that among 9258 women who took an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy, nearly half (n = 4221) took quetiapine [21•]. After controlling for confounding variables, there was no significant association between quetiapine use in early pregnancy and cardiac or other congenital malformations.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at Massachusetts General Hospital reported that among 155 infants with first-trimester exposure to quetiapine, two cases (1.29%) had malformations [33•]. The pooled risk ratio for major malformations in infants exposed to quetiapine [21•, 33•, 34, 35] is estimated at 1.03 (95% CI = 0.89–1.19), which suggests that there is no increased risk of malformations with early exposure to quetiapine compared with the general population.

A Danish study reported that 42 of 174 (24.1%) quetiapine-exposed pregnancies ended in miscarriage [36]. The miscarriage rate in women taking antipsychotic medications during pregnancy was similar to women who were unexposed which suggests that any increased risk in miscarriage was likely related to maternal disease rather than the medication exposure.

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole is the second most commonly used antipsychotic in pregnancy [5] and has generally not been associated with congenital malformations [21•]. In a 2016 review of 1756 pregnancies with aripiprazole exposure, congenital and cardiac malformations were not significantly increased after adjusting for confounding variables [21•]. Bellet and colleagues prospectively followed 86 pregnancies exposed to aripiprazole during first trimester and also did not find an increase in congenital malformations [37•]. However, Montastruc et al. conducted a review in VigiBase, the World Health Organization Global Individual Case Safety Report database, and reported a disproportionate amount of gastrointestinal malformations (palate, esophageal, and anorectal disorders) with aripiprazole exposure [38]. This work relied on spontaneous reporting of defects and has not been replicated.

Several studies have examined infant outcomes with aripiprazole exposure. Galbally et al. completed an investigation of 26 pregnancies with known aripiprazole exposure, 12 of which continued the medication throughout the pregnancy [39•]. The average dose during the first trimester was 17.98 mg/day, and the average dose during the third trimester was 19.77 mg/day. Infants exposed to aripiprazole had an average gestational age at delivery of 37.3 weeks, and their birth weight was significantly lower than the Australian national average birth weight. Additionally, more neonates exposed to aripiprazole required admission to a special care nursery (SCN)/neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) compared with the Australian national average (38.5% vs 16%, p = 0.003). When women who continued aripiprazole throughout pregnancy were compared to those who stopped it earlier in pregnancy, investigators noted a trend towards poorer outcomes in the pregnancies in which aripiprazole was discontinued, but this finding did not reach significance. Bellet and colleagues also reported an increased risk for preterm births (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.06–6.27) and fetal growth retardation (OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.23–7.16) in aripiprazole-exposed pregnancies [37•].

Galbally et al. reported an increase in hypertension in pregnant women taking aripiprazole (15.4% vs 3.7% Australian national average, p = 0.015) [39•]; however, an increase in preeclampsia has not been reported [37•].

Risperidone

There are mixed findings on the association of risperidone and the risk of congenital malformations. In a prospective study of 68 cases of in utero exposure to risperidone from the Benefit Risk Management World Wide Safety database, congenital malformations occurred in 3.8% of pregnancies [40]. Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 432 pregnancies with first-trimester exposure to risperidone, the malformation rate was 5.1% (relative risk [RR] = 1.5, 95% CI = 0.9–2.2). [41]. In contrast to these findings, Huybrecths et al. reported an increase in absolute risk for congenital malformations (RR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.02–1.56) and cardiac malformations (RR = 1.26; 95% CI = 0.88–1.81) in a Medicaid database review of 1566 pregnancies with risperidone exposure after accounting for confounding variables [21•]. These authors were not able to identify a biological mechanism for malformations and described this as a “potential safety signal.” Risperidone exposure in pregnancy has also been associated with a disproportionate amount of gastrointestinal malformations (palate, esophageal, and anorectal disorders), but these data relied on spontaneous reporting of defects and have not been replicated [38].

Paliperidone

Paliperidone is the primary active metabolite of risperidone. Given its less frequent use and that it is a relatively newer medication, available data on use in pregnancy, birth outcomes, and neurodevelopment is limited but may be extrapolated from risperidone data. Two case reports of long-acting injectable paliperidone use during pregnancy [42, 43] and one cohort study (n = 17, of which 10 used long acting injectable formulation) did not show an association with paliperidone use and major congenital malformations [44].

Olanzapine

Olanzapine has not been associated with congenital malformations. Brunner et al. conducted a large review of the Eli Lilly safety database which contained data on 610 prospectively identified pregnancies with olanzapine exposure [45]. Seventy-five percent of the women had first-trimester exposure, and approximately half (44%) continued olanzapine throughout pregnancy. The rate of congenital anomalies (4.4%) was not higher than the 3–5% in the general population. Consistent with Brunner et al.’s findings, Ennis and colleagues determined that the risk for congenital malformation was 3.5% among infants in a meta-analysis of 1090 pregnancies exposed to olanzapine [41]. Huybrechts et al. also did not find an increased risk for congenital malformations or cardiac malformations in a retrospective review of 1394 olanzapine-exposed pregnancies [21•].

A smaller study (n = 24) noted an association with olanzapine use and higher birth weights [46]. However, Boden and colleagues’ larger study (n = 159) did not find this association with birth weight, but did note an association with larger head circumference [47]. The rate of postterm birth, spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and still births associated with olanzapine exposure are consistent with that of the general population [45].

Ziprasidone

Ziprasidone has not been linked to congenital malformations. Huybrechts and colleagues studied 697 pregnancies with ziprasidone exposure [21•]. After accounting for confounding variables, they did not find evidence of an increased risk for congenital malformations overall or for cardiac malformations with ziprasidone exposure. An analysis of 37 prospectively followed ziprasidone-exposed pregnancies also did not find a higher risk of malformations [34].

Clozapine

There is minimal information on clozapine’s use during pregnancy. The Motherisk Program’s review on atypical antipsychotics in pregnancy included six clozapine-exposed pregnancies and reported no malformations [48]. The Motherisk Program also notes a communication with the manufacturer of clozapine reporting that the manufacturer’s database included 523 cases of pregnancy and 22 of those (4.2%) resulted in a malformation.

There are a number of case reports on the use of clozapine during pregnancy including one of a woman pregnant with triplets [49]. Several reports have cited concerns such as decreased variability of fetal heart rate in infants exposed to clozapine in utero [50] and the potential risk for neonatal seizures, floppy infant syndrome, and macrocephaly [47, 51,52,53]. However, there are also a number of case reports indicating no or minimal complications with the use of clozapine in pregnancy [30, 54,55,56,57,58].

Lurasidone

Lurasidone has been considered a favorable choice for antipsychotic use during pregnancy, primarily based on the prior pregnancy drug classification system in which lurasidone was categorized as “B” indicating that animal studies did not show evidence of teratogenicity [59]. Investigation of the reproductive safety of lurasidone is underway by the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics [33].

Infant outcomes: neonatal adaptation and neurodevelopment

Infants exposed to both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been reported to have signs of difficulty adapting after birth. These signs may include fussiness, respiratory issues, neuromuscular changes (floppiness or stiffness), or gastrointestinal problems [60]. As a result, infants may require monitoring in a SCN/NICU. It is not clear how often these symptoms occur or whether they represent infant withdrawal, toxicity, an unknown downstream developmental effect, or exposure to maternal disease. The Australian National Register of Antipsychotic Medication in Pregnancy followed 147 pregnancies with antipsychotic exposure [61]. The investigators found that 37% of the infants had some degree of respiratory distress at birth which was higher than the nationally reported rate of 28%; infants concurrently exposed to mood stabilizers with antipsychotics were six times more likely to have respiratory issues. Almost half (43%) of the infants were admitted to a SCN/NICU, more commonly with exposure to higher doses of antipsychotics or a concurrent mood stabilizer. Another study compared exposure to typical antipsychotics and atypical antipsychotics and found that the infants exposed to typical antipsychotics were more likely to experience postnatal symptoms (21.6% vs 15.6%) including respiratory, digestive, cardiac, and nervous system concerns [34]. Frayne and colleagues found a similar rate of admission to SCN after antipsychotic exposure, 42.5% (n = 87) [62].

Whether neurodevelopment in infants exposed to any antipsychotics is delayed or impaired long term is debated in the literature. Investigators in three studies have reported developmental delays at earlier ages (2, 6, and 9 months) which resolve by 12 to 24 months of age [63,64,65]. Specifically, exposed infants initially had lower scores on standard testing of neuromotor performance [63, 65] and lower scores on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development in areas of cognitive, motor, social-emotional, and adaptive behavior [64]. In a study comparing 33 clozapine exposed infants to 30 infants exposed to risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine, Shao et al. noted that the clozapine-exposed infants had more developmental delays on adaptive behaviors at 2 and 6 months of age but no differences in cognitive, language, motor, or social and emotional development at any age. [66]

Although the majority of studies have documented that developmental delays are temporary, a Danish study suggests that the effects may be long-reaching, based on their assessments of the children through high school [67]. Children who were exposed to antipsychotics (N = 3887) (also included in the category were anxiolytics, hypnotics, and sedatives) were compared to unexposed individuals and those exposed to other psychotropic drugs. Those with antipsychotic exposure (or one of the other drugs included in this category) had higher odds of neurological and mental disorders later in life, scored lower on school exams, and were more apt to require special needs help at school. As noted by the investigators, a major limitation of the study is that the effects of maternal mental and physical health as well as exposure to polypharmacy were not accounted for and may have better explained the outcomes.

Gestational diabetes

Adverse metabolic effects such as obesity and insulin resistance are prevalent among patients who take atypicals. As a result, pregnant women exposed to atypical antipsychotics are at increased risk for gestational diabetes (Table 2) [47, 61, 68•]. Investigators have specifically linked quetiapine and olanzapine with higher rates of gestational diabetes. Park and colleagues conducted a studying using the Medicaid database and compared women who took atypical antipsychotics and continued the medication during pregnancy to those who discontinued the medication upon becoming pregnant [69•]. They reviewed 4533 cases of perinatal quetiapine use and found, after adjusting for confounders, the relative risk for gestational diabetes among women who continued quetiapine during the first half of their pregnancy (n = 1542) compared to those who chose to discontinue (n = 2951) to be 1.28 (95% CI = 1.01–1.62). This did not seem to be a dose-dependent effect. Women who continued olanzapine during pregnancy also had an increased risk of gestational diabetes compared to those who discontinued olanzapine prior to pregnancy.

Aripiprazole has not been linked to gestational diabetes which is attributed to its favorable metabolic profile [5, 37•]. Similarly, lurasidone is characterized as weight-neutral and would not be expected to increase the risk of gestational diabetes, but more investigation is needed. Reports on risperidone and ziprasidone use in pregnancy suggest that both do not increase the risk of gestational diabetes.

Gestational diabetes increases the risk of poor infant outcomes (i.e., preterm birth, macrosmia). Monitoring weight gain and body mass index as well as reinforcing healthy diet and exercise throughout pregnancy is critical to help mitigate risk [70].

Metabolism during pregnancy and drug concentration

Physiologic changes during pregnancy result in an increased metabolism and a resultant decline of antipsychotic serum concentration [71]. The activity of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP2C9 as well as uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) isoenzymes is increased during pregnancy and leads to declines in drug concentration [72]. Additionally, weight gain, plasma volume expansion, and increases in renal clearance are factors that further affect drug concentrations.

In the largest study to date, Westin and colleagues examined plasma concentrations (n = 512) of antipsychotics in 103 women during pregnancy and postpartum [71]. They concluded that serum concentrations during the third trimester were significantly lowered for quetiapine (76% decrease), aripiprazole (52% decrease), and possibly for perphenazine and haloperidol compared with prepregnancy concentrations. They did not find a decrease in plasma concentration of olanzapine and had insufficient data to comment on the physiological effects of pregnancy on ziprasidone, risperidone, or clozapine concentrations. Consistent with other investigations, decreases in quetiapine concentration are attributed to the increased activity of CYP3A4 [73]. The decline in aripiprazole is due to increased CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity. Olanzapine and clozapine are both largely metabolized via CYP1A2, which can decrease in activity during pregnancy, and also undergo glucuronidation via UGT which is significantly increased during gestation. The opposite effects of CYP1A4 and UGT1A4 may prevent significant changes in serum concentration of olanzapine and clozapine during the physiologic changes of pregnancy. Although monitoring of antipsychotic concentrations is not the standard of care and therefore not currently used to guide dosing, the relative decline in drug concentration during pregnancy supports the need for close symptom monitoring. Worsening of symptoms require a dose increase which should be considered prior to adding a psychotropic medication for symptom control. To prevent toxicity, doses increased during pregnancy should be decreased in the first week postpartum because the mother’s metabolism rapidly returns to baseline.

Breastfeeding

When choosing a medication for use during pregnancy, it is also important to consider the postpartum period and breastfeeding. Antipsychotics are transferred through the breastmilk to the infant, but the relative exposure is much lower than in utero exposure. There is insufficient evidence to suggest that breastfeeding is contraindicated with any antipsychotic. Risperidone has a relatively higher transfer to the breastmilk than olanzapine or quetiapine [74], but adverse events have not been reported [75, 76]. Multiple sources have advised against breastfeeding while taking clozapine [77,78,79]. There was one case report of agranulocytosis as well as sedation, but this was not well described [53]. There was also a case of speech delay, but it was not clear that the clozapine was causative [80]. The risks and benefits of breastmilk exposure to clozapine must be carefully considered, and if a mother chooses to breastfeed while on clozapine, we recommend monitoring the infant for sedation and obtaining monthly labs to monitor white blood cell and neutrophil count.

Discussion

The overall risk of congenital malformations with early pregnancy exposure to typical or atypical antipsychotics is minimal. There is a concern that risperidone, and by extension paliperidone, may slightly increase the risk of malformations. For this reason, risperidone and paliperidone are not recommended as first-line agents during pregnancy. However, continuation of the most effective regimen is necessary for women with chronic illness and is often preferable to switching to alternative antipsychotics which may be less effective. In cases where a patient is at increased risk for gestational diabetes, it is reasonable to consider an antipsychotic less likely to cause metabolic issues including a typical antipsychotic.

Because of the physiologic changes during pregnancy, metabolism of antipsychotics increases. As a result, reduction in medication dose to decrease potential exposure to the fetus increases the risk of sub-therapeutic treatment. The lowest effective antipsychotic dose for the patient is recommended, and antipsychotic doses may need to be increased during pregnancy.

Infants exposed to antipsychotics in utero may experience time-limited adaptation difficulties immediately after birth. There is also a potential delay in motor development that seems to resolve by the time the child is 2 years of age. Antipsychotics are not contraindicated in breastfeeding, although clozapine requires careful consideration and monitoring.

Studies of maternal mental health and perinatal and infant outcomes are confounded by difficulty controlling for the impact of exposure to maternal disease state compared to medication exposure. Larger scale studies that attempt to address this issue would be beneficial for clinicians who counsel patients on the relative risks of treatment options.

Conclusion

In general, it is recommended that women who need to take an antipsychotic during pregnancy continue the antipsychotic that has been most effective in symptom remission. It is possible that higher doses will be required as the pregnancy progresses. Further study on risperidone is needed to better understand its relationship with malformations, and at this time, we would not consider it a first-line choice for use during pregnancy.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(2):177–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.2082.

Camsari U, Viguera AC, Ralston L, Baldessarini RJ, Cohen LS. Prevalence of atypical antipsychotic use in psychiatric outpatients: comparison of women of childbearing age with men. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(6):583–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0465-0.

Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Antipsychotic treatment of adults in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(10):1346–53. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m09863.

Toh S, Li Q, Cheetham TC, Cooper WO, Davis RL, Dublin S, et al. Prevalence and trends in the use of antipsychotic medications during pregnancy in the U.S., 2001-2007: a population-based study of 585,615 deliveries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(2):149–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0330-6.

Park Y, Huybrechts KF, Cohen JM, Bateman BT, Desai RJ, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic medication use among publicly insured pregnant women in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(11):1112–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600408.

Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, Jeste DV. Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients: a review of the literature. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(3):173–88.

Viguera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ, Newport DJ, Stowe Z, Reminick A, et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatr. 2007;164:1817–24.

Jablensky AV, Morgan V, Zubrick SR, Bower C, Yellachich L-A. Pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal complications in a population cohort of women with schizophrenia and major affective disorders. Am J Psychiatr. 2005;162(1):79–91.

Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, Gonzalez-Quintero VH. Prenatal depression restricts fetal growth. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(1):65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.07.002.

Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and newborn: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2006;29(3):445–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.003.

Steer RA, Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Fischer RL. Self-reported depression and negative pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1093–9.

Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hosli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(3):189–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050701209560.

Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: a meta-analytic investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(6):737–46.

Vameghi R, Amir Ali Akbari S, Sajjadi H, Sajedi F, Alavimajd H. Correlation between mothers’ depression and developmental delay in infants aged 6-18 months. Global J Health Sci. 2015;8(5):11–8. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n5p11.

Leight KL, Fitelson EM, Weston CA, Wisner KL. Childbirth and mental disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(5):453–71. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.514600.

Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, Garrod D et al. Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2011;118 Suppl 1:1–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x.

Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Update on overall prevalence of major birth defects—Atlanta, Georgia, 1978–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(1):1–5.

Bajaj L, Hambidge S, Nyquist A, Kerby G. Berman’s pediatric decision making. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. World Birth Defects Day. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/features/birth-defects-day/. Accessed 10/18/18 2018.

FDA. Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Final Rule. 2014. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed 5/29/15 2015.

• Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Patorno E, Desai RJ, Mogun H, Dejene SZ, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA psychiatry. 2016;73(9):938–46. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520 Largest study to date examining the risk of congenital malformations after antipsychotic expsoure.

Newham JJ, Thomas SH, MacRitchie K, McElhatton PR, McAllister-Williams RH. Birth weight of infants after maternal exposure to typical and atypical antipsychotics: prospective comparison study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):333–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041541.

Petersen I, Sammon CJ, McCrea RL, Osborn DPJ, Evans SJ, Cowen PJ, et al. Risks associated with antipsychotic treatment in pregnancy: comparative cohort studies based on electronic health records. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):349–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.023.

McCullar FW, Heggeness L. Limb malformations following maternal use of haloperidol. JAMA. 1975;231(1):62–4.

Dieulangard P. Sur un cas d’ectro-phocomelie peutetre d'origine medicamenteuse. Gynecol Obstet. 1966;18:85–7.

Briggs G, Freeman R, Jaffe S. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation 9th edition. 9th ed.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Waes A, Velde E. Safety evaluation of haloperidol in the treatment of hyperemesis Gravidarum. J Clin Pharmacol and J New Drugs. 1969;9(4):224–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/009127006900900403.

Reis M, Kallen B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):279–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e318172b8d5.

Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, Arnon J, Schaefer C, Garbis H, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):317–22.

Lin HC, Chen IJ, Chen YH, Lee HC, Wu FJ. Maternal schizophrenia and pregnancy outcome: does the use of antipsychotics make a difference? Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.011.

Slone D, Siskind V, Heinonen OP, Monson RR, Kaufman DW, Shapiro S. Antenatal exposure to the phenothiazines in relation to congenital malformations, perinatal mortality rate, birth weight, and intelligence quotient score. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128(5):486–8.

Heinonen O, Sloan D, Shapiro S. Birth defects and drugs in pregnancy. Littleton, Massachusetts: Publishing Sciences Group Inc; 1977.

• Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, Freeman MP, Sosinsky AZ, Moustafa D, Marfurt SP et al. Reproductive Safety of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Current Data From the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(3):263–70. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506. Comprehensive evaluation of quetiapine expsoure in pregnancy.

Habermann F, Fritzsche J, Fuhlbruck F, Wacker E, Allignol A, Weber-Schoendorfer C, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and pregnancy outcome: a prospective, cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(4):453–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e318295fe12.

Sadowski A, Todorow M, Yazdani Brojeni P, Koren G, Nulman I. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics given with other psychotropic drugs: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013, 3(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003062.

Sorensen MJ, Kjaersgaard MI, Pedersen HS, Vestergaard M, Christensen J, Olsen J, et al. Risk of fetal death after treatment with antipsychotic medications during pregnancy. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132280. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132280.

• Bellet F, Beyens MN, Bernard N, Beghin D, Elefant E, Vial T. Exposure to aripiprazole during embryogenesis: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(4):368–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3749 Study of the use of aripiprazole in pregnancy and pregnancy and birth related outcomes.

Montastruc F, Salvo F, Arnaud M, Begaud B, Pariente A. Signal of gastrointestinal congenital malformations with antipsychotics after minimising competition bias: a disproportionality analysis using data from Vigibase((R)). Drug Saf. 2016;39(7):689–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0413-1.

• Galbally M, Frayne J, Watson SJ, Snellen M. Aripiprazole and pregnancy: a retrospective, multicentre study. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:593–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.004 Study of the use of aripiprazole in pregnancy and pregnancy and birth related outcomes.

Coppola D, Russo LJ, Kwarta RF Jr, Varughese R, Schmider J. Evaluating the postmarketing experience of risperidone use during pregnancy: pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Drug Saf. 2007;30(3):247–64.

Ennis ZN, Damkier P. Pregnancy exposure to olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, aripiprazole and risk of congenital malformations. A systematic review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116(4):315–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.12372.

Ozdemir AK, Pak SC, Canan F, Gecici O, Kuloglu M, Gucer MK. Paliperidone palmitate use in pregnancy in a woman with schizophrenia. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(5):739–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0496-6.

Zamora Rodriguez FJ, Benitez Vega C, Sanchez-Waisen Hernandez MR, Guisado Macias JA, Vaz Leal FJ. Use of paliperidone palmitate throughout a schizoaffective disorder patient’s gestation period. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):38–40. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-110492.

Onken M, Mick I, Schaefer C. Paliperidone and pregnancy—an evaluation of the German Embryotox database. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21:657–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0828-z.

Brunner E, Falk DM, Jones M, Dey DK, Shatapathy CC. Olanzapine in pregnancy and breastfeeding: a review of data from global safety surveillance. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-6511-14-38.

Babu GN, Desai G, Tippeswamy H, Chandra PS. Birth weight and use of olanzapine in pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):331–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181db8734.

Boden R, Lundgren M, Brandt L, Reutfors J, Kieler H. Antipsychotics during pregnancy: relation to fetal and maternal metabolic effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):715–21. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1870.

McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M, Wilton L, Shakir S, Diav-Citrin O, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):1,478–49.

Sreeraj VS, Venkatasubramanian G. Safety of clozapine in a woman with triplet pregnancy: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;22:67–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2016.04.009.

Yogev Y, Ben-Haroush A, Kaplan B. Maternal clozapine treatment and decreased fetal heart rate variability. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;79(3):259–60.

Stoner SC, Sommi RW Jr, Marken PA, Anya I, Vaughn J. Clozapine use in two full-term pregnancies. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(8):364–5.

Di Michele V, Ramenghi L, Sabatino G. Clozapine and lorazepam administration in pregnancy. Eur Psychiatry. 1996;11(4):214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-9338(96)88396-9.

Dev V, Krupp P. Adverse event profile and safety of clozapine. Rev Contem Pharmacoth. 1995;6:197–208.

Duran A, Ugur MM, Turan S, Emul M. Clozapine use in two women with schizophrenia during pregnancy. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(1):111–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881107079171.

Gupta N, Grover S. Safety of clozapine in 2 successive pregnancies. Can J Psychiatr. 2004;49(12):863.

Waldman MD, Safferman AZ. Pregnancy and clozapine. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(1):168–9.

Sethi S. Clozapine in pregnancy. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48(3):196–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.31586.

Barnas C, Bergant A, Hummer M, Saria A, Fleischhacker WW. Clozapine concentrations in maternal and fetal plasma, amniotic fluid, and breast milk. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(6):945. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.6.945.

Cruz MP. Lurasidone HCl (Latuda), an Oral, once-daily atypical antipsychotic agent for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. P T. 2011;36(8):489–92.

Auerbach JG, Hans SL, Marcus J, Maeir S. Maternal psychotropic medication and neonatal behavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992;14(6):399–406.

Kulkarni J, Worsley R, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Van Rheenen TE, Wang W, et al. A prospective cohort study of antipsychotic medications in pregnancy: the first 147 pregnancies and 100 one year old babies. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e94788.

Frayne J, Nguyen T, Bennett K, Allen S, Hauck Y, Liira H. The effects of gestational use of antidepressants and antipsychotics on neonatal outcomes for women with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(5):526–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12621.

Johnson KC, LaPrairie JL, Brennan PA, Stowe ZN, Newport DJ. Prenatal antipsychotic exposure and neuromotor performance during infancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):787–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.160.

Peng M, Gao K, Ding Y, Ou J, Calabrese JR, Wu R, et al. Effects of prenatal exposure to atypical antipsychotics on postnatal development and growth of infants: a case-controlled, prospective study. Psychopharmacology. 2013;228(4):577–84.

Hurault-Delarue C, Damase-Michel C, Finotto L, Guitard C, Vayssiere C, Montastruc JL, et al. Psychomotor developmental effects of prenatal exposure to psychotropic drugs: a study in EFEMERIS database. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2016;30(5):476–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcp.12209.

Shao P, Ou J, Peng M, Zhao J, Chen J, Wu R. Effects of clozapine and other atypical antipsychotics on infants development who were exposed to as fetus: a post-hoc analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123373.

Wibroe MA, Mathiasen R, Pagsberg AK, Uldall P. Risk of impaired cognition after prenatal exposure to psychotropic drugs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(2):177–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12754.

• Hatters Friedman S, Moller-Olsen C, Prakash C, North A. Atypical antipsychotic use and outcomes in an urban maternal mental health service. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2016;51(6):521–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217417696739 Evaluation of atypical antipsychotic use and pregnancy and birth outcomes.

• Park Y, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Cohen JM, Desai RJ, Patorno E, et al. Continuation of atypical antipsychotic medication during early pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(6):564–74. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17040393 Evaluation of atypical antipsychotic use and gestational diabetes.

Clark CT, Wisner KL. Treatment of Peripartum bipolar disorder. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2018;45(3):403–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2018.05.002.

Westin AA, Brekke M, Molden E, Skogvoll E, Castberg I, Spigset O. Treatment with antipsychotics in pregnancy: changes in drug disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(3):477–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.770.

Anderson GD. Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics: a mechanistic-based approach. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(10):989–1008. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200544100-00001.

Paulzen M, Goecke TW, Kuzin M, Augustin M, Grunder G, Schoretsanitis G. Pregnancy exposure to quetiapine—therapeutic drug monitoring in maternal blood, amniotic fluid and cord blood and obstetrical outcomes. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:252–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.09.043.

Uguz F. Second-generation antipsychotics during the lactation period: a comparative systematic review on infant safety. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):244–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000491.

Risperidone. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Bethesda (MD)2006.

Lurasidone. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Bethesda (MD)2006.

McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R, Easter A, Gilvarry E, Glover V, et al. British association for psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31(5):519–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117699361.

Pacchiarotti I, Leon-Caballero J, Murru A, Verdolini N, Furio MA, Pancheri C, et al. Mood stabilizers and antipsychotics during breastfeeding: focus on bipolar disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(10):1562–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.08.008.

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia. Part 3: Update 2015 Management of special circumstances: Depression, Suicidality, substance use disorders and pregnancy and lactation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16(3):142–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2015.1009163.

Mendhekar DN. Possible delayed speech acquisition with clozapine therapy during pregnancy and lactation. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2007;19(2):196–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.2007.19.2.196.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Clark reports grants from NICHD-K23 grant, during the conduct of the study, and Miller Medical Communications as a speaker for CME activities on postpartum depression.

Hannah K. Betcher and Catalina Montiel declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Betcher, H.K., Montiel, C. & Clark, C.T. Use of Antipsychotic Drugs During Pregnancy. Curr Treat Options Psych 6, 17–31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-019-0165-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-019-0165-5