Abstract

This study assesses the moderating role of personal attitude in the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intentions among management science students in Pakistan. Convenience sampling techniques were implied, and self-administrative closed-ended questionnaires were used to collect primary data from the sample of 331 enrolled students in the department of management science at different universities of Pakistan. The data were analyzed using the multiple regression model to test the study hypothesis. Findings of the study revealed that entrepreneurial knowledge positively and significantly influences entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, this study also reported that personal attitude has a significant moderating role and strengthening the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention. Theoretically, this paper confirms the importance of entrepreneurial intention. Practically, it suggested that universities should pay attention to designing their curriculum based on entrepreneurial knowledge, fostering a positive attitude that can shape the entrepreneurial intentions of students. It can ultimately help to force innovations in the marketplace and create job opportunities in the economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is vital to the nation’s economic, social, and technological development. The global policymakers and academicians have a common opinion that entrepreneurship is considered to be the engine of economic growth, prosperity, and wellbeing of society (Bosma et al., 2012) in both developed and developing countries. Entrepreneurship brings structural changes in the economy (Schumpeter, 1942) and changes the social, technological, and organizational environment (Gaddam, 2008). Many researchers agreed that entrepreneurship positively contributes to economic development and growth through innovation (Huggins & Thompson, 2015) and job creation (Baron & Shane, 2008; Fayolle, 2007; Frederick et al., 2006; Ibrahim & Lucky, 2014). Government institutions and international organizations around the world have made efforts to encourage their peoples to engage in entrepreneurial activities. These activities, directly and indirectly, contribute to the overall economy at the national and individual levels. The individuals are actively engaged in business matters for being their own or others; they meet their expenditure and to support their families (Bosma et al., 2012). Entrepreneurship plays the role of social and economic equalizer (Acs et al., 2004) and a potential platform to ensure the stability in the economy by creating job opportunities and innovations (Brush et al., 2009).

The field is yet to be studied more because entrepreneurship is considered to be a vast discipline with blurred boundaries due to a lack of clear conceptual frameworks (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). While going through previous studies, the term entrepreneurial intentions seems to be more worthy because it is considered to be the ultimate representative of entrepreneurship practice (Mueller et al., 2008). Tshikovhi and Shambare (2015) studied entrepreneurial knowledge and intention with a moderating role of personal attitude. Entrepreneurship education/knowledge is an instrument used to enhance entrepreneurial activity (Bischoff et al., 2018). A number of universities offer several degree courses, and they provide skill-specific knowledge to university graduates. It is necessary for the effective creation and successful continuation of the entrepreneurial venture. Several studies stated that entrepreneurship education is relatively new, and research findings are contradictory on effectiveness and value (Martin et al., 2013; Nabi et al., 2017, 2018, Rauch & Hulsink, 2015). However, much debate exists on entrepreneurship to understand nature and importance in social, economic, and technological development (Wach & Wojciechowski, 2016).

Realizing the importance of entrepreneurship in national economic development, the Government of Pakistan and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have also initiated various programs. It supports the national and provincial levels to promote entrepreneurial activities in the country. Among these, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Enterprise Forum (MITCEF) Association of Pakistan is the registered association which is actively engaged in the promotion of entrepreneurial activities in the state by developing entrepreneurship promotion programs, introduces the business acceleration programs (BAP), and conducts conferences with particular focus on innovation and entrepreneurship. The higher education of Pakistan has developed the National Business Education Accreditation Council (NBEAC). NBEAC aims to promote business education, focusing on simulating entrepreneurship education and culture in public and private universities in Pakistan. However, these initiatives are not enough because Pakistan is the largest country with a growing population of youth and sixth-largest country in term of the population that share a total of 2.23% of the total population of the world (DHS, 2019). The large population of Pakistan is under the age of 30, which is comprised of 60% of the total population (Asma, 2018). According to an economic survey in Pakistan by Go (2019), 23.3% of the population live below the poverty line and earn less than $1.25 per day. According to Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (2018) most of the peoples are poor and unemployed. The situation is exacerbated every year because the number of labor force increases rapidly (Zreen et al., 2019). Similarly, this situation is also faced by professional degree holders and fresh graduates in securing jobs (Farrukh et al., 2019). In this condition, entrepreneurship not only attracts a mechanism for economic growth and development but also is treated as a solution for creating jobs and opportunities for the young generation in Pakistan.

Therefore, it is imperative to empirically investigate the role of entrepreneurial knowledge in shaping the entrepreneurial intention of university students in Pakistan. To our knowledge, there are few studies exist on entrepreneurship in Pakistan. Still, they did not systematically analyze the entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention with a moderating role of personal attitude. These studies found the positive attitude of youth towards entrepreneurial activities and indicate a strong future acceptance of entrepreneurship as a profession (Kemal & Mahmood, 1998; Mathias & Williams, 2014; Ali et al., 2011; Khurrum et al., 2008; Williams & Shahid, 2014). This study is designed to fill this gap and empirically investigate the role of entrepreneurial knowledge in shaping entrepreneurial intention among university students in Pakistan. This research contributes to entrepreneurship literature in the following ways. First, this research is conducted to develop a comprehensive view of entrepreneurial intention in Pakistan based on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Second, this research is conducted to study the moderating role of personal attitude towards entrepreneurial intention.

Apart from the introduction, this study has the following sections. The section “Theoretical background and empirical literature” presents theoretical and empirical literature, and the section “Research methodology” covers the research methodology. The section “Results” contains the results from statistical analysis and discussion. Finally, the “Discussion” and “Conclusion and implications” sections discuss the conclusion, recommendations, and limitations of the study.

Theoretical background and empirical literature

Entrepreneurship is considered to be the driving force of innovation and global competitiveness among newly established innovative firms and existing ones (Casson, 2003; Chaudhry & Munir, 2010; Shane, 2003). It promises benefits for economic growth and stability and guarantees individual, organizational, regional, and national success through introducing innovations in the marketplace. The entrepreneurship activities help to reduce unemployment by creating new jobs and sustain the employment levels in society (Roxas, 2014; Roxas et al., 2007; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Gibb (1997) urges that entrepreneurship is a practice of learning, experience, mistakes, and failures. Studies indicate a linear and positive relationship between innovation and entrepreneurship (Harris, 2011; Huggins & Thompson, 2015). Thus, entrepreneurship is a long-term goal, and it helps to overcome the prevailing unemployment rates by opening opportunities for job seekers (Atef & Al-Balushi, 2015). The theoretical roots of entrepreneurship are strong, and it is connected with sociology and psychology (Fayolle & Liñán, 2014). Empirically, research work on entrepreneurship starts with the significant contribution of Shapiro about three decades ago (Shapero, 1985Shapero & Sokol, 1982). The model of implementing entrepreneurial ideas presented by Bird (1988) specifically focuses on the potential value of entrepreneurial intentions and planned behavior theory proposed by Ajzen (1991). These two cognitive-based theories are the main theories generally adopted to study entrepreneurship intention. This study uses the theory of planned behavior; it is sufficient to explain how a person’s interest reflects the behavior of a person doing something. In other words, the theory of planned behavior explains how people act in a particular way. In the entrepreneurial context, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) contributes to our understanding of the emergence of entrepreneurial behavior before observing the action.

Entrepreneurial intention and theory of planned behavior (TPB)

The theory of planned behavior is an intention-based model that explains individual intentions to perform a particular behavior and explain new venture formation. The theory of planned behavior proposed by Ajzen (1991) and in offering the sound and most applicable theoretical framework in understanding entrepreneurship while including social, environmental, and organizational factors (Liñán, 2004; Liñán, 2008; Tkachev & Kolvereid, 1999). The central postulate of this theory is three incidents determine that intention for any human behavior, attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, which cumulatively produced behavioral intention. TPB allows researchers to understand intention from social as well as personal perceptions (Ajzen, 1991). It is suggested that attitude does not directly work on behavior, but it is indirectly through intention. Hence, the attitude is influenced by many exogenous variables, which indirectly act through intention. Several studies argued that TPB had emerged as one of the powerful and most influential constructs in explaining the intention of potential entrepreneurs to start a venture (Harris and Gibson, 2008; Liñán & Chen, 2009). The more positive a person’s attitude towards action, the more likely it is that he will develop the intention to engage in that action.

However, such studies in the area of entrepreneurship have found empirical supports to the theory of Planned Behavior (Gibb, 1997; Athayde, 2009; Lee et al., 2006; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Kolvereid & Moen, 1997; Casson, 2003; Roxas et al., 2007; Roxas, 2014; Shane, 2003, Anjum et al., 2018; Farrukh et al., 2019). Based on the finding of these studies, it can be argued that an individual takes decisions to create new firms based on only three motivational factors as postulated in TBP (attitude towards behavior, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms).

Entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention

Entrepreneurial knowledge is considered to be the main ingredient of entrepreneurial activities and establishing new businesses because of its high impact on entrepreneurial intentions leading to individual, organizational, and national success through economic sustainability (Øystein Widding, 2005). It refers to the content knowledge of an individual regarding business operations, resource availability, opportunity identification, exploitation, and other entrepreneurial activities (Roxas, 2014). It represents the potential entrepreneur’s capability to recognize opportunities and pursue them and enable an entrepreneur to comprehend, extrapolate and interpret information, and resources and uniquely utilize them, producing new products or services with specific attributes (Roxas, 2014).

Entrepreneurial knowledge comes from the interaction of the individual with a society where he/she belongs, education, training (Liñán, 2004; Martin et al., 2013), and on-hand practice, so they are considered more important in the development of human resources (Turker & Sonmez Selçuk, 2009). When entrepreneurial education is combined with prior entrepreneurial knowledge, people are pushed (Hisrich, 1990) towards entrepreneurship as a career direction (Henderson & Robertson, 2000). Whereas Pittaway et al. (2015)) found that the participants of the study were more inclined towards entrepreneurial activities to enhance personal skills, for enjoyment, to be knowledgeable, to do something for the society, and to bring the ideas forth for practice in the society they belong, Lindquist et al. (2015) suggest that the entrepreneurial career choice by an individual also depends on the genetic inheritance and transmission of taste for entrepreneurship and the parental transfer of capital and other resources that lead towards a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship.

The entrepreneurial knowledge has been studied by different researchers in different ways, in different settings, and at different times. Aspects of entrepreneurial knowledge studies include product, market, organizational, and financial level (Øystein Widding, 2005); exploitation of resources, opportunity identification, planning for new venture creation, financial planning, product designing, market development, strategic policies, and innovation practice (Shane & Venkatraman, 2000); organizational behavior, strategic management, finance, and human resource management (Hindle, 2007); and growth management, idea generation and innovation, risk and rationality, creativity and public relations, social links, and obligations (Fiet, 2001).

Entrepreneurial activities are carried out by an entrepreneur for numerous factors; few of them are intrinsic and extrinsic personal outcomes that are most valued (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994). The primary exogenous factor considered to have a more significant impact on entrepreneurship is the cognitive capability of entrepreneur and external pressure from the social, cultural, and institutional environment (Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard, & Rueda-Cantuche, 2011a) and entrepreneurial education syllabus and course customarily carried out by educational institutions (Krueger & Carsrud, 1993) which potentially shape the development of perceptions in terms of starting a business through evoking a positive attitude towards it. So, the entrepreneurial knowledge and skills are critical in setting up businesses and harness the perceptions and beliefs that may be favorable or unfavorable inclination and behavior towards entrepreneurial activities (Roxas, 2014). The resources and entrepreneurial activities are based on entrepreneurial knowledge, when appropriately utilized for opportunity-seeking and resource allocation entrepreneurial activities become successful (Fritsch & Wyrwich, 2014; Huggins & Williams, 2011; Mueller et al., 2008). Here, the regions play the role of incubators for the growth and development of entrepreneurial activities, where ideas are converted into innovation yielding valuable new knowledge in the field (Huggins & Williams, 2011).

The role of entrepreneurial knowledge in developing a positive influence on entrepreneurial intentions is highly encouraged (Roxas, 2014). At the same time, these intentions shaped by entrepreneurial knowledge and factors from the environment plays a significant role in showing a positive behavior of individual towards establishing a business venture (Fayolle et al., 2006; Liñán, Urbano, & Guerrero, 2011b). The study conducted by Roxas (2014) found a positive relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and intentions to start a business.

An entrepreneurial intention represents the degree of commitment towards self-employment and new venture formation (Ajzen, 1991). It is the degree of commitment of an individual towards some future target behavior, which is termed as planned social behavior by Krueger (1993), and these planed attitudes and intentions lead to shape individual behavior (Ajzen, 1991). It represents the level of interest of individuals in business creation and the business creation process. It is the state of mind of entrepreneurs that dictates him/her to develop new business ideas and the ways to implement them (Boyd & Vozikis 1994). Thompson (2009) refers to entrepreneurial intentions as self-knowledge convictions of that individual to start a business venture someday in the future.

Entrepreneurial knowledge and intention: moderating role of personal attitude

Attitude is a mental status referring to the readiness level based on the prior experience dictating an individual’s response and behavior to the objects and situation which he/she encounters in everyday life (Allport, 1935). In simple, attitude can also be termed as a person’s likes and dislikes. Krech and Crutchfield (1948) defined attitude as the amalgamation of an individual’s emotional, perceptual, motivational, and cognitive processes concerning the place and society he/she belongs. It refers to the probability of specific behavior an individual show in a specific situation (Campbell, 1950). According to Eagly and Chaiken (1993), attitude is a psychological tendency of an individual to show a degree of favor or disfavor in evaluating a particular entity, while in contrast to the traditional perceptions of attitude, Wilson et al. (2000) state that individuals have many attitudes regarding an object to different points of time. Athayde (2009) found a positive attitude of participants, and (Duval-Couetil et al., 2014) obtained results of 91% in favor of entrepreneurship as a career.

An attitude is intangible hypothetical construct introduced by scholars to account for a body of a phenomenon and only be observed in terms of an individual’s behavior and self-reports on any subject context-dependent matter (Schwarz & Sudman, 1992). These are the reflection of memory that a person holds and expressed through the cognitive and communicative process. It can be observed in terms of the intentionality of an individual towards starting a new venture, and a positive attitude surely has a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention. The antecedents of attitude and intentions shape the behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Krueger et al., 2000). Krueger et al. (2000) found that cognitive infrastructure is needed to identify and sense new opportunities when they arise, whereas the environmental factors greatly influence the individual towards entrepreneurial activities (Begley et al., 2005).

Personal attitude forms the basis for entrepreneurial intentions, which acts as one’s judgment to run and own a business (Krueger et al., 2000; Fatoki, 2010). The environment plays a vital role in the formation of attitude and behavior towards entrepreneurship by providing information that makes an individual knowledgeable. As humans are social organisms, they interact with the environment all the time and face different elements that comprise that environment, including cultural, social, economic, political, technical, and demographic. They share and receive the information and use it for means of personal use. So the environment plays a vital role in shaping attitudes and intentions (Fatoki, 2010Jack & Anderson, 2002) through the generation of knowledge. Hence, the approval of the environment proves to be the pass for individuals to engage freely in entrepreneurial activities (Liñán, 2008). Individuals show a positive attitude and greater intention directly or indirectly attached to an entrepreneurship background (Wyrwich, 2015).

Fayolle et al. (2006) found that intentions act as a catalyst in the process of an individual’s action-planning and action-taking and it is believed that intentions are the strong predictors of individual behavior and attitude towards entrepreneurial activity (Van Gelderen et al., 2008). While in deciding to be an entrepreneur, people go through a process of planned and carefully constructed mental/thinking processes, which itself relies heavily upon intentions and personal attitude (Bird, 1988; Krueger, 1993; Tkachev & Kolvereid, 1999).

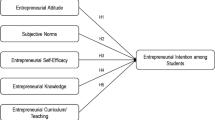

Altogether the existing literature, including theories and empirical models, examines the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intentions. The most common models are the model of an entrepreneurial event (Shapero & Sokol, 1982), the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), and the model of implementing entrepreneurial ideas (Bird, 1988). These models are as the base for recent studies done in the field of entrepreneurship (Krueger et al., 2000; Fayolle et al., 2006; Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard, & Rueda-Cantuche, 2011a; Liñán, 2004; Lee et al., 2006; Tshikovhi & Shambare, 2015; Ali et al., 2011; Liñán & Chen, 2009) focused on different factors and dimensions yielding in a complex body of knowledge. In an attempt to determine the role of entrepreneurial knowledge in shaping entrepreneurial intentions with the moderating role of personal attitude, we construct the following analytical framework based on the theory of planned behavior (in Figure 1; Study Model).

-

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant positive relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention.

-

Hypothesis 2: Personal attitude moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention.

-

Hypothesis 3: There is a significant positive relationship between personal attitude and entrepreneurial intention.

Research methodology

Sample and procedure

The study is explanatory and determining the entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Pakistan using a deductive approach. The sample selection is based on Krueger et al. (1993), who mentioned that to predict entrepreneurial intentions, sample selection should be made from the population which is on the edge of choosing a career population. Therefore, we collect data from the five public universities in three different cities Islamabad, Rawalpindi, and Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Specifically, these are Karakoram International University Gilgit-Baltistan, Fatima Jinnah Women University Rawalpindi, Pir Mehar Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi, Federal Urdu University of Science and Technology Islamabad, Capital University Islamabad. We used a convenience sampling method to collect primary data through a self-administrative closed-ended questionnaire. Our sample consisted of 500 university students full and part-time enrolled in the department of management sciences. The number of students enrolled in these cities of Pakistan taken in the sample frame is deemed to significantly representing the entire population of business graduates enrolled in different universities all over Pakistan. The respondents vary in terms of personality and views, so more accurate and generalized results can be obtained. The questionnaire was distributed among students in five selected universities, considering the ratio of participation from each city equally. A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed and 379 were returned, making a 75.8% response rate, while 48 were subsequently discarded due to incomplete data and missing information. The final sample consists of 331 participants; among these, 173 were male (52.3%) and 158 were female (47.7%) students approximately. The key features of the sample are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 reports that 52.3% (173) of the respondents were male, while 47.7% (158) were female respondents. It implies that more males than females were participating in the study. The majority of participants (30.8%) were 20–22 years old, while 29% of the respondents were 17–19 years old. Similarly, 24.8% of participants were 24–25 years old, and only 15.4% of participants were 26–28 years old. The total respondents who participate in a survey from the MBA class were 52.2% (173) and 47.7% (158) from the BBA class. The majority of students had some working experience in different sectors, and they have their own family business or working part-time; among that, 20.8% (69) of students had 1 year, 26.9% (89) 1 year, 7.3% (24) 3 years, and 2.1% (7) 4 years of experience. In comparison, 42% (142) out of 331 respondents had zero experience.

Study instruments and measurements

The questionnaire was used as an instrument for data collection. The survey questionnaire consisted of four parts, and it was developed based on Chen et al. (1998) and Liñán and Chen, 2009. The first part of the questionnaire consisted of questions on the demographic profile of respondents. The second part had six items measuring entrepreneurial knowledge. The six statements were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items were adopted from studies based on the theory of planned behavior (Chen et al., 1998; Fayolle & Degeorge, 2006; Krueger et al., 2000; Roxas, 2014). The third part consisted of five items measuring personal attitude adopted from (Liñán & Chen, 2009). The respondents were asked to state their agreement/ disagreement on the statement on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Part 4 had six items, measuring entrepreneurial intention adopted from Liñán and Chen (2009). They were assessed using 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Reliability and validity of instruments

Cronbach’s alpha test was employed to assess the reliability and validity of the instruments, as suggested by Nunnaly (1978), for retaining scale items Hair et al., (2003). We employed the reliability and validity test towards the indicators that are used to measure the variables entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitude, and entrepreneurial intention, as shown in Table 2.

The ordinary least square (OLS) method was employed to estimate the model. To test the mediating effect of personal attitude, we used the regression analysis procedure specified by Baron and Kenny (1986). First, “symptom patterns, the dependent variable, was regressed on an independent variable, which determined the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Second, symptom patterns were regressed moderator variables, which determined the effect of the moderator variable on the dependent variable. Third, symptom patterns were regressed on the product of perceived stress (Verheul et al., 2015) and perceived social support, which determined the interaction effect of the independent and moderator variables on the dependent variable.”

Results

The data obtained from the participants were coded for the statistical analysis using SPSS-21 to test the hypothesis of the study and carried out empirical results, including a profile of respondents, descriptive statistics and correlation, and regression analysis. Furthermore, Baron and Kenny’s (1986) moderation regression method were used to test the moderating effect of personal attitude. The reliability test-Cronbach alpha for entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitude, and entrepreneurial intention was .87, .75, and .88, respectively. The higher value indicates satisfactory results, and items are considered reliable. The overall Cronbach alpha test indicates reliable results and satisfactory matching with Nunnaly (1978).

The mean, standard deviation of all variables, and Pearson correlation coefficients between variables are reported in Table 2. Usually, the Pearson correlation test is used to determine the degree and nature (inverse and direct), and it is used to measure the bivariate relationship between numerical variables on a Likert scale (Pallant, 2013).

Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables. These correlation analysis results reveal that the entrepreneurial knowledge recorded strong and significantly associated with entrepreneurial intention (r = .533, sign ≤ .1). Similarly, a positive and significant correlation between entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude (r = .379, sign ≤ .1). Besides, the results also showed that the correlation coefficient (r) between personal attitude and entrepreneurial intention (r = .537 sign ≤ .1) was highly significant among the relationship between study variables. The correlation between entrepreneurial knowledge and level of education was also significant and positive (r = .173, sign ≤ .05). The positive and significant relationship between age and education (r = .369, sign ≤ .05) indicates that the education level is increased with the age of respondents. Similarly, age and work experience are also positive and have a significant relation (r = .496a, sign ≤ .05), indicating work experience increases with the age of the respondent. There is a significant positive relationship between gender and entrepreneurial knowledge (r = .193a, sign ≤ .05) indicating that the probability of males is more attracted to entrepreneurial knowledge.

Furthermore, in cross-sectional data, explanatory variables are strongly correlated with each other. It can create a multicollinearity problem. Under this condition, the analysis of regression is meaningless and confusing because it is difficult to identify which independent variable influences the dependent variable. To check the multicollinearity among the explanatory variables, we used two diagnostic tests, (a) Eigenvalues and (b) variance inflation factor. The test statistics allow us to conclude that there is no multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. The eigenvalues are neither closed to zero nor more significant than five variance inflation factor values.

The regression results and hypothesis of study testing are presented in Table 3. The proposed hypothesis was tested using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) moderation regression method. Baron and Kenny proposed the following four-step procedure to test the moderation effect. In the first step, we estimate the relationship between control variables and the dependent variable (controlling entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude). In the second step, we estimate the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable (controlling personal attitude and other control variables, e.g., age, gender, education, and experience). After that, we estimate the relationship between moderator and dependent variable (controlling independent variable, e.g., entrepreneurial knowledge and age, gender, education, and experience). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3 indicates the influence of control and moderating variables. The four-step procedure was applied to test the hypothesis of the study; in the first step, the control variables (age, gender, education, and experience) are entered in the regression model and run on the entrepreneurial intention. The first step results indicate that age, education, and experience are significant and positively related to entrepreneurial intentions. With an increase in age, education, and experience, there is a probability of an increase in entrepreneurial intentions of management science students. The second step was regressed entrepreneurial knowledge on entrepreneurial intention, and a positive and significant relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and intention (β = .515, p < .000) was found. The third step was regressed personal attitude on entrepreneurial intention. It seems that personal attitude was significantly and positively associated with entrepreneurial intention (β = .517, p < .000), while in the fourth step, regressed factor term (entrepreneurial knowledge × personal attitude) on entrepreneurial intention, results revealed that factor term is significant and has positive influence on entrepreneurial intention (β = .604, p < .000). More specifically, a positive and significant relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and intention indicates that practical knowledge can stimulate and increase entrepreneurial intentions of the student towards career consideration in entrepreneurship. Thus, this is the fact that entrepreneurial intentions equip learners to effectively take challenges and complexities in decision making associated with the career in entrepreneurship.

Furthermore, individuals with strong personal attitudes are intensively motivated to take advantage of their current knowledge effortfully. The overall results fully support our hypothesis (H1, H2, and H3) and indicate that entrepreneurial knowledge contributes positively towards the entrepreneurial intention of management science students in different universities of Pakistan. Furthermore, personal attitude significantly moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention. The model diagnostic tests, high R2, adjusted R2, and F-statistics, show the model is excellent and fit. Furthermore, the assumption of the classical linear regression model such as collinearity.

Discussion

The social and economic benefits of entrepreneurial activities intensively studied by scholars and policymakers are interested in sort out the various factors that shape entrepreneurial intention. The entrepreneurial intention strengthens the degree of effort of individuals and students to carry out future entrepreneurial behavior. For this, it is necessary to understand the factor that shapes entrepreneurial intention (Tolentino et al., 2014). This study, based on the theoretical framework of the theory of planned behavior (AJzen, 1991) attempted to understand the role of entrepreneurial knowledge in shaping entrepreneurial intention. This study was focused on finding the strength and level of entrepreneurial intentions with the moderating role of personal attitude among university students in Pakistan. The overall results support a significant and robust relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention (β = .515, p < =.01). The moderation effect of personal attitude, which refers to the entrepreneurial attitude, was found positive and significant, which strengthen the relationship between independent and dependent variables (β = .604, p < =.01). The finding of this study suggests that personal attitude has a strong and highly significant effect on the entrepreneurial intention of business management students in Pakistan. Our findings are related to the study of Tshikovhi and Shambare (2015). They investigate the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention with the mediating role of personal attitude. They focused on the impact of action-based entrepreneurship training on entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude in developing entrepreneurial intentions. They found a significant influence of entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude on entrepreneurial intentions. The strength between study variables was noted as (β = .510, p < .000) between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention. The most interesting findings of this study were the impact of personal attitude on entrepreneurial intentions (β = .624, p < .000) while in comparison with the result of our study with moderating role of personal attitude was noted (β = .604, p < .000). On the other side, the personal impact of personal attitude was noted (β = .517, p < .000) stronger as compared to the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intentions.

Similarly, Ali et al. (2011) studied the entrepreneurial intentions of 480 masters of business administration (MBA) students in different universities of Pakistan. They found a positive and significant relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intentions. Liñán (2004) also studied entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intentions with mediating the role of attitude, feasibility, and social norms. The results showed a weak and positive relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial knowledge (β = .164, p < .010). The results are somewhat different. These relationships were observed much more robust in our study, and this may be due to the different aspects of the study or due to the change in the geographical location of the study and time. Roxas (2014) also studied the effect of entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intentions with the mediation of perception of desirability and self-efficacy. Their finding also supports the positive relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and intention. Many other studies (Liñán, 2004; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Harris, 2011; Huggins & Thompson, 2015; l; Huggins & Williams, 2011; Wyrwich, 2015; Tan & Yoo, 2015) support a positive relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitude, and entrepreneurial intentions. The findings from our study corroborate evidence from past studies that emphasized the role of entrepreneurial knowledge in predicting entrepreneurial intention and this relation stronger by the personal attitude.

Conclusion and implications

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of entrepreneurial knowledge in shaping entrepreneurial intention with the moderating role of personal attitude among management science students enrolled in different universities of Pakistan. The study hypothesized that there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and intention. Besides, the moderator of the model, e.g., personal attitude (entrepreneurial attitude), strengthens the relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge and intention. The empirical results support the hypotheses of the study. The study concludes that entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude play a pivotal role in shaping individual entrepreneurial intention, which is the ultimate predictor of the venture creation process. In light of the findings of this study, several policy implications can be gleaned. Prominent among these are that universities play an important role in shaping entrepreneurial knowledge and the need to enhance the entrepreneurial knowledge among the university students in Pakistan by designing a well-crafted curriculum for entrepreneurship development. Second, successful entrepreneurs in different universities in Pakistan are invited to narrate their success store, assigning them as a mentor for entrepreneurially oriented students. Third, seminars, conferences, and internship programs that may enhance the ability of students to participate in entrepreneurship activities are conducted. Thus, collective effort is required to boost entrepreneurship in Pakistan. It can help to improve the economy of Pakistan by creating employment opportunities and innovations in the marketplace.

Limitations and future research

Our study encountered some limitations; first, the variables discussed in the study are deemed limited to individual personality shaping the entrepreneurial intentions. There are many other factors like entrepreneurial education, culture, family, the role of institutions, and demographic variables. Future research may focus on these variables and add them to their study to find more accurate findings. Second, our study examined the only department of management science students and generalized them to all department students in Pakistan. Future research can be conducted comprehensively by including the different tiers of professions. Third, the sample selected for the study was only 331 from three cities Islamabad, Rawalpindi, and Gilgit of Pakistan. Future studies may increase the sample size and include participants from different cities to obtain more detailed results.

Data Availability

I declare that this article is in its original form. Data used for testing of hypothesis is accumulated first hand from participants, and the literature added is appropriately cited. The data obtained is available with the corresponding author in SPSS format, if required and requested.

Abbreviations

- TPB:

-

theory of planned behavior

- SPSS 21:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 21)

- MITCEF:

-

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Enterprise Forum

- BAP:

-

business acceleration programs

- NBEAC:

-

the National Business Education Accreditation Council

References

Acs, Z. J., Arenius, P., Hay, M., & Minniti, M. (2004). Global entrepreneurship monitor.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ali, A., Topping, K. J., Tariq, R. H., & Wakefield, P. (2011). Entrepreneurial attitudes among potential entrepreneurs. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 5(1), 12–46.

Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In A handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Worcester: Clark University Press.

Anjum, T., Nazar, N., Sharifi, S., & Farrukh, M. (2018). Determinants of entrepreneurial intention in perspective of theory of planned behavior. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 40(4), 429–441.

Asma, K. (2018). Pakistan currently has the largest percentage of young people in its history: Report. Dawn, https://www.dawn.com/news/1405197

Atef, T. M., & Al-Balushi, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship as a means for restructuring employment patterns. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(2), 73–90.

Athayde, R. (2009). Measuring enterprise potential in young people. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 481–500.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Baron, R. A., & Shane, S. A. (2008). Entrepreneurship: A process perspective (2nd ed.). Mason: Thomson South-Western.

Begley, T. M., Tan, W. L., & Schoch, H. (2005). Politico-economic factors associated with interest in starting a business: A multi-country study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 35–55.

Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453.

Bischoff, K., Volkmann, C. K., & Audretsch, D. B. (2018). Stakeholder collaboration in entrepreneurship education: An analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystems of European higher educational institutions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(1), 20–46.

Bosma, N., Wennekers, S., & Amorós, J. E. (2012). Global entrepreneurship monitor, 2011 extended report: Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial employees across the globe. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA).

Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4), 63–77.

Brush, C. G., De Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurs. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24.

Campbell, D. T. (1950). The indirect assessment of social attitudes. Psychological Bulletin, 47(1), 15–38.

Casson, M. (2003). The entrepreneur: an economic theory. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Chaudhry, I. S., & Munir, F. (2010). Determinants of low tax revenue in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 30(2), 439–452.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

DHS. (2019). Pakistan demographic and health survey (pp. 2017–2018). National Institute of Population Studies Islamabad.

Duval-Couetil, N., Gotch, C. M., & Yi, S. (2014). The characteristics and motivations of contemporary entrepreneurship students. Journal of Education for Business, 89(8), 441–449.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt.

Farrukh, M., Lee, J.W.C., and Shahzad, I.A. (2019). Intrapreneurial behavior in higher education institutes of Pakistan: The role of leadership styles and psychological empowerment. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education.

Fatoki, O. O. (2010). Graduate entrepreneurial intention in South Africa: Motivations and obstacles. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(9), 87.

Fayolle, A. (2007). Entrepreneurship and new value creation: The dynamic of the entrepreneurial process. Cambridge University Press.

Fayolle, A., & Degeorge, J. M. (2006). Attitudes, intentions, and behavior: New approaches to evaluating entrepreneurship education. International entrepreneurship education. Issues and newness, 74-89.

Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666.

Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programs: A new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(9), 701–720.

Fiet, J. O. (2001). The pedagogical side of entrepreneurship theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(2), 101–117.

Frederick, H. H., Kuratko, D. F., & Hodgetts, R. M. (2006). Entrepreneurship: Theory, process, and practice. Cengage Learning.

Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2014). The long persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925–2005. Regional Studies, 48(6), 955–973.

Gaddam, S. (2008). Identifying the relationship between behavioral motives and entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical study based on the perceptions of business management students. The Icfaian Journal of Management Research, VII(5), 35–55.

Gibb, A. A. (1997). Small firms’ training and competitiveness. Building upon the small business as a learning organization. International Small Business Journal, 15(3), 13–29.

Hair, J. F., Babin, B., Money, A. H., & Samouel, P. (2003). Essentials of business research methods. John Willey & Sons.

Harris, R. (2011). Models of regional growth: Past, present, and future. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(5), 913–951.

Harris, M., & Gibson, S. (2008). An examination of the entrepreneurial attitudes of US versus Chinese students. American Journal of Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 1.

Henderson, R., & Robertson, M. (2000). Who wants to be an entrepreneur? Young adult attitudes to entrepreneurship as a career. Career Development International, 5(6), 279–287.

Hindle, K. (2007). Teaching entrepreneurship at university: From the wrong building to the right philosophy. Handbook of research in entrepreneurship education, 1, 104–126.

Hisrich, R. D. (1990). Entrepreneurship/entrepreneurship. American Psychologist, 45(2), 209–222.

Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2015). Entrepreneurship, innovation, and regional growth: A network theory. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 103–128.

Huggins, R., & Williams, N. (2011). Entrepreneurship and regional competitiveness: The role and progression of policy. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23(9–10), 907–932.

Ibrahim, N. A., & Lucky, E. O. I. (2014). Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial skills, environmental factor, and entrepreneurial intention among Nigerian students in UUM. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management Journal, 2(4), 203–213.

Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487.

Kemal, A. R., and Mahmood, Z. (1998). The urban informal sector of Pakistan: Some stylized facts. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. PIDE Research Report No. 161.

Khurrum, S., Bhutta, M., Rana, A. I., & Asad, U. (2008). Owner characteristics and health of SMEs in Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(1), 130–149.

Kolvereid, L., & Moen, Ø. (1997). Entrepreneurship among business graduates: Does a major in entrepreneurship make a difference? Journal of European Industrial Training, 21(4), 154–160.

Krech, D., & Crutchfield, R. S. (1948). Theory and problems of social psychology. MacGraw-Hill.

Krueger, N. F. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 18(1), 5–21.

Krueger, N., & Brazeal, D. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91–104.

Krueger, N. F., & Carsrud, A. L. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 5(4), 315–330.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of business venturing, 15(5), 411–432.

Lee, S. M., Lim, S. B., Pathak, R. D., Chang, D., & Li, W. (2006). Influences on student’s attitudes toward entrepreneurship: A multi-country study. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2(3), 351–366.

Liñán, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccola Impresa/Small Business, 3, 11–35.

Liñán, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257–272.

Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617.

Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C., & Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2011a). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 195–218.

Liñán, F., Urbano, D., & Guerrero, M. (2011b). Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: Start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23(3–4), 187–215.

Lindquist, M. J., Sol, J., & Van Praag, M. (2015). Why do entrepreneurial parents have entrepreneurial children? Journal of Labor Economics, 33(2), 269–296.

Martin, B. C., McNally, J. J., & Kay, M. J. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 211–224.

Mathias, B. D., & Williams, D. W. (2014). The impact of role identities on entrepreneurs’ evaluation and selection of opportunities. Journal of Management, 43(3), 892–918 0149206314544747.

Mueller, P., Van Stel, A., & Storey, D. J. (2008). The effects of new firm formation on regional development over time: The case of Great Britain. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 59–71.

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299.

Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Liñán, F., Akhtar, I., & Neame, C. (2018). Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 452–467.

Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

Øystein Widding, L. (2005). Building entrepreneurial knowledge reservoirs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(4), 595–612.

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Pakistan employment trends. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

Pallant, J. (2013). SPSS survival manual. McGraw-Hill Education.

Pittaway, L. A., Gazzard, J., Shore, A., & Williamson, T. (2015). Student clubs: Experiences in entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal. 1–27.

Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204.

Roxas, B. (2014). Effects of entrepreneurial knowledge on entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal study of selected South-east Asian business students. Journal of Education and Work, 27(4), 432–453.

Roxas, H. B., Lindsay, V., Ashill, N., & Victorio, A. (2007). An institutional view of local entrepreneurial climate. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and sustainability, 3(1), 1–28.

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Creative destruction. Capitalism, socialism, and democracy.

Schwarz, N., & Sudman, S. (Eds.). (1992). Context effects in social and psychological research. Springer Verlag.

Shane, S. A. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Shapero, A. (1985). The entrepreneurial even. College of Administrative Science, Ohio State University.

Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship.

Tan, W. L., & Yoo, S. J. (2015). Social entrepreneurship intentions of nonprofit organizations. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 103–125.

Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694.

Tkachev, A., & Kolvereid, L. (1999). Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11(3), 269–280.

Tolentino, L., Sedoglavich, V., Lu, V., Garcia, P., & Restubog, S. (2014). The role of career adaptability in predicting entrepreneurial intentions: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85, 403–412.

Tshikovhi, N., & Shambare, R. (2015). Entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitudes, and entrepreneurship intentions among South African Enactus students. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 13(1), 152–158.

Turker, D., & Sonmez Selçuk, S. (2009). Which factors affect the entrepreneurial intention of university students? Journal of European Industrial Training, 33(2), 142–159.

Van Gelderen, M., Brand, M., van Praag, M., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E., & Van Gils, A. (2008). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions using the theory of planned behavior. Career Development International, 13(6), 538–559.

Verheul, I., Block, J., Burmeister-Lamp, K., Thurik, R., Tiemeier, H., & Turturea, R. (2015). ADHD-like behavior and entrepreneurial intentions. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 85–101.

Wach, K., & Wojciechowski, L. (2016). Entrepreneurial intentions of students in Poland in the view of Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 4(1), 83–94.

Williams, C. C., & Shahid, M. S. (2014). Informal entrepreneurship and institutional theory: Explaining the varying degrees of (in) formalization of entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal, 8(1), 1–25.

Wilson, T. D., Lindsey, S., & Schooler, T. Y. (2000). A model of dual attitudes. Psychological Review, 107(1), 101–126.

Wyrwich, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship and the intergenerational transmission of values. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 191–213.

Zreen, A., Farrukh, M., Nazar, N., & Khalid, R. (2019). The role of internship and business incubation programs in forming entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis from Pakistan. Journal of Management and Business Administration. Central Europe, 27(2), 97–113.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Muhammad Sadil Ali and Imtiaz Hussain for their friendly support while conducting this research study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This research project was carried out and finalized by TH, the corresponding author, under the supervision of MZ, while SA contributed to the data analysis and reporting with the use of SPSS-21.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hussain, T., Zia-Ur-Rehman, M. & Abbas, S. Role of entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude in developing entrepreneurial intentions in business graduates: a case of Pakistan. J Glob Entrepr Res 11, 439–449 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-021-00283-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-021-00283-0