Abstract

Purpose of Review

The goal of this paper is to review the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) research that informed World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for PMTCT and describe the impact of worldwide scale-up of PMTCT programs and antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage. The impact of these interventions on new pediatric infections and infected children’s morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa are reviewed.

Recent Findings

The IMPAACT PROMISE study demonstrated that triple therapy consisting of tenofovir (TDF), lamivudine (3TC), and lopinavir/ritonavir (LPVr) or zidovudine (AZT), 3TC, and LPVr initiated in the first trimester reduced vertical transmission at 2 weeks of age to 0.6% and 0.5%, respectively, supporting the current WHO Option B+ recommendation for PMTCT. However, increased adverse pregnancy outcomes in the AZT- and TDF-based triple therapy arms were reported when compared with the AZT prophylaxis arm (low birth weight [20.4% and 16.9% vs. 8.9%; p = 0.004] and premature deliveries [19.7% and 18.5% vs. 13.5%; p = 0.09], respectively). Implementation of Option B+ for PMTCT has led to significant reductions in vertical transmission rates, including elimination of new pediatric infections in some countries. The WHO declared elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission (MTCT) in Cuba in 2015 and in Armenia, Belarus, and Thailand in 2016.

Summary

Globally, new pediatric HIV infections have declined significantly since the introduction of effective antiretroviral regimens for PMTCT. Perinatal HIV prevention clinical trials conducted in sub-Saharan Africa informed WHO PMTCT guidelines which led to implementation of PMTCT programs worldwide, leading to a 47% reduction in new pediatric infections since 2009. Support from The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and UN agencies has enabled scale-up of national PMTCT programs, and increased antiretroviral coverage (47% globally) for infected children has led to a decline in HIV/AIDS-related mortality in children. Implementation strategies that improve retention in care and adherence to ART in pregnant and breastfeeding HIV-infected women is critical to ensure that more countries achieve the elimination of MTCT (eMTCT) targets. Assessing the effectiveness of new antiretroviral drugs, including fixed-dose combinations and long-acting formulations, is key to improving ART adherence and reducing the emergence of viral resistance mutations. In addition, interventions to prevent HIV transmission in adolescents and young adults is critical for reducing new HIV infections worldwide. Innovative interventions to improve adherence to ART are required to further improve the survival of HIV-infected children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, 2.1 million children are living with HIV, 90% of whom reside in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The high prevalence of HIV infection in women of reproductive age continues to drive the pediatric HIV epidemic in Africa as the majority of new pediatric infections are acquired through mother-to-child HIV transmission (MTCT). With increasing access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) and pediatric HIV treatment, there has been a significant decline in new pediatric infections and reduced mortality of infected children, respectively [2]. Multiple perinatal HIV prevention clinical trials conducted in resource-limited settings have demonstrated that various antiretroviral regimens administered during pregnancy and breastfeeding can significantly reduce MTCT [3,4,5,6,7,8].These clinical trial results informed the World Health Organization (WHO) ART guidelines, which provide guidance for implementation of PMTCT programs in resource-limited settings, and have demonstrated that MTCT rates can be reduced to less than 5% in breastfeeding populations. With support from The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and The Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, in partnership with the Ministries of Health, scale-up of national PMTCT programs has led to a significant decline in new pediatric infections worldwide. However, the 2015 United Nations (UN) target of less than 40,000 babies being born infected with HIV worldwide was not achieved due to inadequate PMTCT coverage in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa [2]. The current UN target for elimination of MTCT (eMTCT) is less than 20,000 new infections by 2020 [9]. To achieve this target, additional commitment from national governments, civil society, and people living with HIV is required to achieve the well-document interventions needed for eMTCT. This article reviews the coverage of PMTCT services, HIV prevention clinical trials that have informed WHO policy on PMTCT, and ART coverage in children, all of which impact pediatric HIV incidence and overall child morbidity and mortality.

Epidemiology

An estimated 160,000 children < 15 years of age contributed to the new-incident cases of HIV infections reported worldwide in 2015 [1]. Most young children living with HIV are infected from their mothers either during pregnancy, labor, and delivery or post-natally during breastfeeding in settings where breastfeeding is essential to overall infant survival. In resource-limited countries, up to one-third of infections occur during breastfeeding [10]. The global plan to eliminate new HIV infections in children by 2015, with the introduction of lifelong universal ART treatment for all pregnant and breastfeeding women, has made a significant contribution to the reduction of HIV infections in children. Overall, the proportion of pregnant women living with HIV receiving ART in priority countries has increased from 36% in 2009 to approximately 80% in 2015 [11]. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates that a total of 1.3 million pediatric infections were averted by PMTCT between 2010 and 2015 [2].

In contrast, new infections among adolescents and young adults have continued to fuel the HIV pandemic. These new infections in young persons are occurring despite proven effective preventative interventions such as condom use and pre-exposure prophylaxis. Among the 2.1 million newly infected adults in 2015, 34% were young persons between the ages of 15 and 24 years, and yet this age group represents only 22% of the adult population [12]. In 2016, the WHO launched new treatment guidelines that emphasize early treatment of adults, adolescents, and children which should further decrease the risk of HIV transmission to sexual partners and MTCT of HIV [13].

In 2015, 1.1 million AIDS-related deaths occurred, with approximately 1.0 million among adults and 190,000 among children less than 15 years of age. HIV is the leading cause of death among adolescents in Africa and second leading cause worldwide [14]. Approximately 150 adolescents die from AIDS-related causes every day [15]. With scale-up of ART, children are surviving into adolescence; however, more support is needed to ensure their ongoing care and improve adherence to ART in order to reduce both mortality and new infections among adolescents.

Prevention of Mother-to-Child (PMTCT) HIV Transmission Research

MTCT remains the main mode of HIV transmission in infants and young children, accounting for more than 90% of total pediatric HIV infections [1]. Large-scale efforts to reduce MTCT began in 1994 in developed countries following the results of the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) protocol 076, which demonstrated that administration of zidovudine (AZT) from 14 weeks of gestation and continuing during pregnancy, labor, and to the newborn reduced MTCT by 66% in non-breastfeeding populations [16]. However, this was an expensive and complex regimen and not easily scaled up in developing countries, which accounted for more than 90% of MTCT and were predominantly breastfeeding communities. Attempts to reduce the cost and duration of the regimen were examined in the Thai CDC short course trial and the PHPT (Perinatal HIV Prevention Trial) Thailand trial with similar results. Unfortunately, when the same regimen was evaluated in a breastfeeding population in West Africa, its effectiveness was significantly lower [4, 6,7,8]. Results from the PETRA (Perinatal HIV prevention Trial) study in East and South Africa demonstrated that the combination of AZT and lamivudine (3TC) initiated by the mother during the last trimester of pregnancy and given to the infant for 6 weeks post-natally significantly reduced MTCT rates in a breastfeeding population, albeit with a relatively high administration cost [3]. Results from the HIVNET 012 landmark study released in 1999 showed that administration of single-dose nevirapine (NVP) at onset of labor and a single dose given to the newborn reduced MTCT by 47% at 6 weeks of age [5]. This single-dose NVP regimen was cheap, simple, and easy to administer. However, while these cost-effective perinatal antiretroviral regimens for PMTCT were implemented in developing countries, multiple challenges were encountered, such as long-term health behavior monitoring, adherence to prescribed treatments, reporting bias, and more [17,18,19,20].

Despite implementation of the perinatal antiretroviral regimens for PMTCT in sub-Saharan Africa, continued breastfeeding reduced the effectiveness of these interventions. Other clinical trials conducted included the implementation of infant NVP prophylaxis for 6 weeks and/or 6 months post-delivery to reduce breastfeeding transmission [21, 22] and the Kesho Bora study in Kenya which demonstrated that triple therapy in a breastfeeding population can significantly reduce MTCT to less than 5% at 6 weeks of age [23]. All of these clinical trials informed WHO ART guidelines for implementation of PMTCT in resource-limited settings.

In 2016, the IMPAACT (International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials) perinatal HIV prevention clinical trial, PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere), demonstrated that triple ART consisting of tenofovir (TDF), 3TC, and lopinavir/ritonavir (LPVr) during pregnancy was superior (1% vs. 0.6%) to prophylaxis with AZT and 3TC in reducing vertical transmission [21]. These findings support the current WHO ART guidelines for eMTCT which recommend that all HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women should initiate triple ART and continue treatment for life (Option B+) [24]. The recommendations by UNAIDS/WHO have been established to fast-track the end of AIDS for children, adolescents, young women, and expectant mothers. These recommendations involve triple action, as follows: (i) start free by eliminating new HIV infection in children (aged 0–14 years); (ii) stay free by reducing the number of new HIV infections among adolescents and young women (aged 10–24 years); and (iii) AIDS free by providing millions of children and adolescents with ART by 2018, and also by providing millions of children and adolescents with HIV treatment by 2020 [2].

Implementation of PMTCT Services in Resource-Limited Settings

In October 2000, a team of technical experts convened in Geneva, Switzerland and recommended use of ART for PMTCT [25]. In June 2001, 189 countries endorsed a Declaration of Commitment at the UN General Assembly and set the goal to reduce MTCT of HIV by 20% in 2005 and by 50% by 2010 [15]. Low attendance at antenatal care services and knowledge of HIV sero status among pregnant women were a hindrance to successful roll-out and scale-up of early PMTCT programs [11]. Therefore, to achieve meaningful reduction in MTCT, national programs had to adopt the WHO recommended four-pronged approach: primary prevention of HIV among women (prong 1); prevention of unintended pregnancies among HIV-infected women (prong 2); support for PMTCT through practical measures to reduce MTCT including antiretroviral prophylaxis, infant-feeding counselling and support, and maternal care including safe delivery practices, post-natal care and early childhood care (prong 3); and provision of care and support to HIV-infected women, their infants, and their families (prong 4) [2]. Several initiatives by private and public entities were launched, including the MTCT-Plus initiative, with the aim of providing lifelong care and support for HIV-infected women and their families [26].

The burden of MTCT remained high in 2003, with an estimated 700,000 children newly infected with HIV—more than 90% of these infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa [27]. In 2004, the WHO released new guidelines that expanded on the 2000 guidelines and included ART for pregnant women with a low CD4 cell count or AZT from the second trimester for women with no indication for ART [27]. Single-dose NVP (sdNVP) remained an option chosen in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa due to costs and simplicity of administration. However, ART coverage was still low and in 2005 only about 11% of pregnant women living with HIV received antiretroviral prophylaxis [28].

In 2006, the WHO released guidelines to address the December 2005 Abuja Call to Action, with the aim of expanding access and use of ART in resource-constrained settings [28, 29]. The 2006 guidelines emphasize the importance of giving ART to all pregnant women living with HIV who need treatment for their own health and use of more efficacious regimens for those in whom ART is not yet recommended. With more international funding given to resource-poor countries, more pregnant women living with HIV in low-income countries were able to access ART and prophylaxis and coverage increased to 33% in 2007 compared with only 10% in 2004 [30, 31].

In 2009, further guidance on infant feeding in the context of HIV was released by the WHO along with new guidelines recommending earlier initiation of ART and the extension of ART during breastfeeding for the mother and/or child [31,32,33]. However, additional commitment from individual governments was urgently needed to rapidly scale up treatment and bring new pediatric infections to below 5%. In 2012, the WHO released revisions to the 2009 guidelines that included initiating treatment for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women and continuing the treatment for life (Option B+) [34]. The guidelines had the advantage of unifying ART treatment options for adults, pregnant women, and adolescents, making scale-up easier. Since the release of these guidelines, the WHO has recommended an antiretroviral drug regimen including TDF, 3TC, and efavirenz as a fixed-dose combination of one tablet once a day. The 2016 consolidated guidelines support the test and treat approach for adults and children with the aim of achieving the 90–90–90 treatment target by 2020, where 90% of people know their HIV status, 90% of HIV-infected people are on ART, and 90% of those on treatment achieve viral load suppression [29].

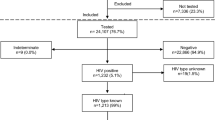

The highest ART coverage was achieved in 2016, with 76% of pregnant women living with HIV receiving antiretroviral drugs to prevent MTCT and a realized reduction in new HIV infections in children of 47% between 2010 and 2016 [35] (Figs. 1 and 2). However, challenges remain, including retaining women in care and on treatment, testing male partners, and sustaining availability and distribution of antiretrovirals and related commodities to the health facilities [36,37,38]. Global success is within reach, with Cuba (2015), Armenia, Belarus, and Thailand (2016) having already been declared by the WHO to have eliminated MTCT [2].

Impact of Antiretroviral Therapy on Morbidity and Mortality of HIV-Infected Children

Without access to ART, HIV-infected children have a very high mortality of 30% by 1 year of age; peripartum infections have the highest mortality of 50% compared with 26% and 4% for those infected through breastfeeding and uninfected children, respectively [39]. Infants infected in utero tend to progress rapidly to AIDS by 6 months and the majority die by 1 year of age. Without access to ART, 30% and 50% of HIV-infected children die by 1 and 2 years of age, respectively [40]. Maternal HIV infection increases child mortality, and maternal mortality further increases the risk of childhood death [41]. The high childhood mortality in resource-limited settings is due to common childhood illnesses including pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, malnutrition, and opportunistic infections (Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, cytomegalovirus [CMV], disseminated tuberculosis [TB]) which tend to be more severe and occur more frequently in HIV-infected children [41].

Because of the rapid disease progression and mortality in HIV-infected children, early initiation of ART is critical for improved survival. The CHER (Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral Therapy) trial in South Africa demonstrated improved survival in perinatally HIV-infected infants in who ART was initiated before 12 weeks of age [42]. This prompted revision of WHO ART guidelines to recommend that all HIV-infected children below 2 years of age regardless of CD4 cell count and WHO clinical stage should initiate triple ART. In 2015, WHO ART guidelines recommended that all children below 15 years should initiate treatment after diagnosis prior to the current ‘test and treat’ policy for all people living with HIV [43]. Earlier treatment guidelines for HIV-infected children were informed by evidence of the faster disease progression, growth failure, neurocognitive impairment, and high mortality in HIV-infected children [44].

With increasing access to ART for HIV-infected children in developing countries there has been a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality [45]. Globally, 43% of HIV-infected children have access to ART, which has led to a significant decline in mortality, with 120,000 pediatric deaths due to HIV in 2016 compared to 220,000 in 2013 [1]. In addition, ART has reduced morbidity, with improved quality of life and fewer children presenting with opportunistic infections [46, 47]. WHO ART guidelines for children below 3 years of age recommend treatment with two nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) (abacavir or AZT and 3TC) plus one protease inhibitor (PI) (LPVr) [13]. Three-drug regimens remain the gold standard for ART as four-drug regimens have not been found to be superior to triple therapy in children [48]. Fixed-dose combinations of ART have been found to be easier to store and administer and to improve adherence [49].

Treatment as Prevention

UNAIDS set the 90–90–90 target in order to reduce the number of new HIV infections. As an approach to achieve this target, in 2016 the WHO launched a new policy recommendation on clinical HIV treatment and care to treat all people living with HIV regardless of age. According to the WHO, 60% of all low- and middle-income countries and 83% of ‘fast-track’ countries have implemented ‘treat all’ as of July 2017.

However, adolescents are still increasingly contributing to the new infections worldwide and have lower adherence, viral suppression, and retention in care than adults [50,51,52]. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of interventions focused on strengthening the gaps in adolescent HIV care and treatment [53]. More evidence needs to be generated about effective interventions for adults and adolescents that could potentially be scaled up with good outcomes; improving the outcomes of adolescents is key in achieving an AIDS-free generation. The WHO and the Collaborative Initiative for Pediatric HIV Education and Research (CIPHER) have recently set a global research agenda which focuses on areas of testing, treatment, and service delivery to inform global policy change and improve outcomes for adolescents living with HIV [54]. Research priorities include implementation science to document interventions that could improve retention in care and adherence to ART in pregnant and breastfeeding HIV-infected women in order to ensure that countries achieve the eMTCT targets of an AIDS-free generation. Assessing the effectiveness of new antiretroviral drug regimens including fixed-dose combinations and long-acting formulations is key to improving adherence and reducing the emergence of resistance mutations.

Conclusion

In sub-Saharan Africa, PMTCT programs have come a long way from vertical transmission rates of 25–45% in the 1980s to less than 5% in many countries. Clinical trials conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia have informed WHO ART guidelines for PMTCT. With commitment and support from PEPFAR, the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and UN agencies, scale-up of national PMTCT services has occurred worldwide with a target for 100% eMTCT by 2020. Increasing access to ART has led to significant reductions in new pediatric infections but many countries, especially in West Africa, have not yet achieved the targets because of poor access to and/or utilization of PMTCT services. Continued worldwide scale-up of PMTCT programs and emphasis on the other three prongs of the WHO’s approach to PMTCT will lead to further and significant reductions in pediatric HIV. Focusing on adolescent-centered treatment and prevention interventions will reduce the rising incidence of cases of HIV in this vulnerable population. In addition, worldwide scale-up of early ART for HIV-infected children and adolescents is critical for reducing mortality and improving their quality of life. This, however, requires additional political, social, and economic commitment from governments, communities, individuals, and key partners to work together to achieve an AIDS-free generation.

References

UNAIDS. UNAIDS report 2016. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016.

UNAIDS. Start Free, Stay Free, AIDS Free. A super-fast-track framework for ending AIDS Among Children, Adolescents And Young Women By 2020. Geneva: UNAIDS 2016

Petra Study Team. Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1178–86.

Dabis F, Msellati P, Meda N, Welffens-Ekra C, You B, Manigart O, et al. 6-month efficacy, tolerance, and acceptability of a short regimen of oral zidovudine to reduce vertical transmission of HIV in breastfed children in Cote d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. DITRAME Study Group. DIminution de la Transmission Mere-Enfant. Lancet. 1999;353(9155):786–92.

Guay LA, Musoke P, Fleming T, Bagenda D, Allen M, Nakabiito C, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):795–802.

Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, Kim S, Koetsawang S, Comeau AM, et al. A trial of shortened zidovudine regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Perinatal HIV Prevention Trial (Thailand) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(14):982–91.

Shaffer N, Chuachoowong R, Mock PA, Bhadrakom C, Siriwasin W, Young NL, et al. Short-course zidovudine for perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Bangkok, Thailand: a randomised controlled trial. Bangkok Collaborative Perinatal HIV Transmission Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353(9155):773–80.

Wiktor SZ, Ekpini E, Karon JM, Nkengasong J, Maurice C, Severin ST, et al. Short-course oral zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9155):781–5.

UNAIDS PaP. Start Free, Stay Free, AIDS Free: A super fast track framework for ending AIDS among children, adolescents and young women by 2020’. 2016.

Nduati R. Breastfeeding and HIV-1 infection. A review of current literature. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;478:201–10.

UNAIDS. 2015 Progress report on the global plan. 2015. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2774_2015ProgressReport_GlobalPlan_en.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2018.

WHO. Progress report 2016: prevent HIV, test and treat all - WHO support for country impact. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

WHO. Health for the world’s adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

United Nations. Declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS. United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS; 25–27 Jun 2001; Geneva.

Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(18):1173–80.

Aizire J, Fowler MG, Coovadia HM. Operational issues and barriers to implementation of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(2):144–59.

Chi BH, Adler MR, Bolu O, Mbori-Ngacha D, Ekouevi DK, Gieselman A, et al. Progress, challenges, and new opportunities for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV under the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(Suppl 3):S78–87.

du Plessis E, Shaw SY, Gichuhi M, Gelmon L, Estambale BB, Lester R, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Kenya: challenges to implementation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(Suppl 1):S10.

Paintsil E, Andiman WA. Update on successes and challenges regarding mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(1):94–101.

Fowler MG, Coovadia H, Herron CM, Maldonado Y, Chipato T, Moodley D, et al. HPTN 046 Protocol Team. Efficacy and safety of an extended nevirapine regimen in infants of breastfeeding mothers with HIV-1 infection for prevention of HIV-1 transmission (HPTN 046): 18-month results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(3):366–74.

Jamieson DJ, Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, King CC, Kourtis AP, Kayira D, et al. Maternal and infant antiretroviral regimens to prevent postnatal HIV-1 transmission: 48-week follow-up of the BAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9835):2449–58.

Kesho Bora Study Group, de Vincenzi I. Triple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho Bora study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(3):171–80.

Fowler MG, Qin M, Fiscus SA, Currier JS, Flynn PM, Chipato T, et al. Benefits and risks of antiretroviral therapy for perinatal HIV prevention. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1726–37.

WHO. In: WHO, editor. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: selection and use of nevirapine - technical notes. Geneva; 2001.

WHO. Saving mothers, saving families: the MTCT-Plus Initiative. Perspectives and practice in antiretroviral treatment. Case study. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

WHO. AIDS epidemic update: 2003. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

WHO. Abuja PMTCT Call to Action: towards an HIV-free and AIDS-free generation. Abuja: Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) High Level Global Partners Forum; 2005.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

UNICEF. Towards universal access: scaling up HIV services for women and children in the health sector–progress report 2008. New York: UNICEF; 2008.

WHO. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: recommendations for a public health approach-2010 version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

WHO. Rapid advice: antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents-November 2009. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

WHO. Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding. Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

WHO. Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: programatic update. Geneva: WHO; 2012.

UNAIDS. Fact sheet - latest statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016.

Myer L, Phillips TK. Beyond "Option B+": understanding antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, retention in care and engagement in ART services among pregnant and postpartum women initiating therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(Suppl 2):S115–22.

Besada D, Rohde S, Goga A, Raphaely N, Daviaud E, Ramokolo V, et al. Strategies to improve male involvement in PMTCT Option B+ in four African countries: a qualitative rapid appraisal. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:33507.

Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, Iorpenda K, Wringe A. Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18588.

Becquet R, Marston M, Dabis F, Moulton LH, Gray G, Coovadia HM, et al. Children who acquire HIV infection perinatally are at higher risk of early death than those acquiring infection through breastmilk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e28510.

Little K, Thorne C, Luo C, Bunders M, Ngongo N, McDermott P, et al. Disease progression in children with vertically-acquired HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: reviewing the need for HIV treatment. Curr HIV Res. 2007;5(2):139–53.

Modi S, Chiu A, Ng'eno B, Kellerman SE, Sugandhi N, Muhe L. Understanding the contribution of common childhood illnesses and opportunistic infections to morbidity and mortality in children living with HIV in resource-limited settings. AIDS. 2013;27(Suppl 2):S159–67.

Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, Babiker AG, Steyn J, Madhi SA, et al. CHER Study Team. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2233–44.

WHO. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva: Switzerland; 2015.

Barlow-Mosha L, Musiime V, Davies MA, Prendergast AJ, Musoke P, Siberry G, et al. Universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected children: a review of the benefits and risks to consider during implementation. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21552.

Penazzato M, Prendergast A, Tierney J, Cotton M, Gibb D. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children under 2 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD004772.

L-B MR, Drouin O, Bartlett G, Nguyen Q, Low A, Gavriilidis G, et al. Incidence and prevalence of opportunistic and other infections and the impact of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(12):1586–94.

Peacock-Villada E, Richardson BA, John-Stewart GC. Post-HAART outcomes in pediatric populations: comparison of resource-limited and developed countries. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e423–41.

Kekitiinwa A, Cook A, Nathoo K, Mugyenyi P, Nahirya-Ntege P, Bakeera-Kitaka S, et al. Routine versus clinically driven laboratory monitoring and first-line antiretroviral therapy strategies in African children with HIV (ARROW): a 5-year open-label randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1391–403.

Penazzato M, Palladino C, Sugandhi N. Prioritizing the most needed formulations to accelerate paediatric antiretroviral therapy scale-up. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12(4):369–76.

Ferrand RA, Briggs D, Ferguson J, Penazzato M, Armstrong A, MacPherson P, et al. Viral suppression in adolescents on antiretroviral treatment: review of the literature and critical appraisal of methodological challenges. Tropical Med Int Health. 2016;21(3):325–33.

Kim SH, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2014;28(13):1945–56.

Lamb MR, Fayorsey R, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Viola V, Mutabazi V, Alwar T, et al. High attrition before and after ART initiation among youth (15-24 years of age) enrolled in HIV care. AIDS. 2014;28(4):559–68.

Murray KR, Dulli LS, Ridgeway K, Dal Santo L, Darrow de Mora D, Olsen P, et al. Improving retention in HIV care among adolescents and adults in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184879.

WHO, CIPHER, IAS. A global research agenda for adolescents living with HIV Research for an AIDS free generation. WHO/HIV/2017.33. Geneva: WHO; 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Philippa Musoke, Zikulah Namukwaya, and Linda Barlow Mosha declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pediatric Global Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Musoke, P., Namukwaya, Z. & Mosha, L.B. Prevention and Treatment of Pediatric HIV Infection. Curr Trop Med Rep 5, 24–30 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-018-0137-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-018-0137-7