Abstract

Morbid obesity often serves as a contraindication to organ transplantation. Furthermore, metabolic complications developed in the peri-operative period and long term after transplant are associated with high mortality. As bariatric surgery is an acceptable measure to treat morbid obesity, it may serve also the transplant population before and after transplant.Methods A review of the literature was done, combined with our own experience with bariatric surgery in kidney and liver transplant recipients before, during, and after transplantation.ResultsPreliminary data show that bariatric surgery seems to be feasible in morbidly obese patients in the setting of transplantation, though associated with high post-operative complication rate. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYBG) are both effective in the kidney transplant population while LSG is the preferred approach for liver transplant patients.ConclusionsAlthough bariatric surgery in the transplant population is not yet extensively studied and is mostly reported in small series, it seems a useful approach for the treatment of morbid obesity in these high-risk patients. Comparative data regarding optimal timing and type of bariatric procedure and long-term results are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Commentary

The higher prevalence of obese patients evaluated for liver and kidney transplant is growing. It is estimated that the prevalence of obesity is 20 to 30% in liver transplant recipients and approaching 60% of patients undergoing renal transplantation [1, 2]. Often, obesity is a relative barrier or contraindication to transplantation and is inadequately addressed by medical therapy. The reasons for this high prevalence are twofold. First, the promotion of end-stage organ disease by obesity and the associated comorbidities (type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease). Second, the increase in body weight often seen after transplantation due to maintenance immunosuppressive therapy with steroids and improve general health and appetite following transplantation [3, 4]. Specifically, the morbidly obese patients who undergo organ transplantation tend to gain weight following the procedure [5].

This vicious cycle of obesity, end-stage disease, transplant, and obesity can be broken with bariatric surgery (BS).

BS in the peri-transplant patient is not yet extensively studied and comparative data on long-term outcomes regarding optimal timing and type of bariatric procedure are lacking.

The major cause of mortality in transplant patients is associated with cardiovascular sequela related to obesity [6]. Performing any major surgical procedure on obese patients is more difficult, takes longer, and is subject to a higher rate of operative and peri-operative complications [7, 8]. The surgical outcomes are worse in obese patients when compared with their non-obese counterparts [9, 10]. Large studies show that among kidney transplant recipients, obesity is associated with a higher risk of allograft failure and death [9,10,11,12].

Nevertheless, the only successful remedy for these patients, in the long run, is BS [6].

Currently, there are no universally set guidelines regarding body mass index (BMI) cutoff for potential transplant patients, and yet, most institutions have upper limits for BMIs above which they will not perform the transplant.

Kidney

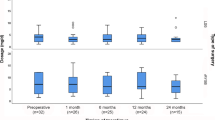

First, we should distinguish the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients from the kidney transplant populations which display different systemic and surgical characteristics. Use of BS has been relatively uncommon among kidney transplant candidates and recipients despite otherwise qualifying indications. On the one hand, delaying BS would not address the technical complications of morbidly obese patients after kidney transplantation. Furthermore, a gastric leak, though an uncommon complication, could be more complicated to manage in a patient on immunosuppressive medication than in chronic renal failure. If sepsis were to develop, it would be conceivable that lowering the immunosuppression would be necessary thereby increasing the risk for graft rejection. Nevertheless, a number of epidemiologic studies with large samples of ESRD patients have indicated paradoxically inverse associations between classic risk factors for cardiovascular disease and mortality [13]. Our experience shows a good experience with 24 ESRD patients undergo laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) or laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), and demonstrates that BS as an effective bridge to kidney transplant with 67% (n = 16) of patients proceeded to kidney transplantation following successful weight reduction in 95% of patients. The mean weight before the transplant was 84 kg and the mean BMI is 29 kg/m2. Mean follow-up post-transplant of 24 months shows that the weight did not increase following transplantation.

In the kidney transplant patients, we demonstrate that the level of immunosuppressive drugs remained stable in both surgical groups (LSG and LRYGB) without the need for any significant changes in drug dosage. In addition, there were no incidences of graft loss or major graft complications, while weight reduction was maintained together with improvement in comorbidities [14].

Liver

When discussing peri-transplant liver patients, there are three options pre-, during, and post-transplant. We are one of the first transplant centers worldwide that offer bariatric procedure for transplanted patients [14,15,16]. There is a lack of experience worldwide performing BS as a bridge to transplantation, with only a few small series [17,18,19].

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is considered the most common chronic liver disease in the Western world [20, 21]. NASH describes a spectrum of liver injury caused by triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes and ranges in severity from benign steatosis to steatohepatitis and ultimately fibrosis and cirrhosis [22]. In 1980, Ludwig et al. [23] named the condition of NASH to describe the liver disease seen in 20 patients without a history of alcohol abuse who demonstrated histologic evidence of marked hepatic steatosis associated with lobular hepatitis, focal necrosis with inflammatory infiltrates, and Mallory bodies. Most of these patients were female, were obese, and had obesity-related diabetes [23]. Over the past three decades, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has emerged as the most common liver disease in the Western world affecting an estimated 25% of the adult population [24]. As a result, in 2017, NASH-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represented 18% of all HCC listings to liver transplant which was an 8.5-fold increase from 2002, and the trend is still steadily growing at approximately 1.9 percentage points per year over the last 4 years [25]. Recently, NASH has become the second leading indication for liver transplantation [26].

Specifically, to this population, it has the potential to influence the incidence of NASH in the post-transplant setting. BS is associated with an improvement of all NASH histologic features. Takata and Lin [27] reported promising results concerning metabolic comorbidities but significantly higher post-operative complication rates compared to the general population. There remains of no consensus on which bariatric modality is best suited for the patient with cirrhosis [28]. Current available data suggest that the less invasive laparoscopic approach would be safer to perform in cirrhotic patients. In general, LRYGB provides the most potential for weight loss but may have a greater risk of vitamin deficiencies compared to LSG that may further lead to progressive hepatic dysfunction.

Both compensated and uncompensated cirrhosis are associated with significantly increased rates of mortality in patients having elective surgery compared with patients without liver disease [29]. BS in cirrhotic patients should be done only in very selected patients, particularly with low model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores without significant portal hypertension [29].

Combined BS and liver transplantation may prolong operative time and complexity of the procedure. In addition, inadequate immunosuppressive medication absorption and poor nutritional status of the patients immediately after transplant may complicate and limit the use of this approach. Campsen et al. [30] described the first case report of combined BS at the time of liver transplant. In addition to weight reduction at 6-month follow-up, the patient had a resolution of her type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension and no post-operative complications. Recently published by our group, a series of 3 patients who underwent simultaneous liver transplant and sleeve gastrectomy [16]. The 3 patients with a median BMI of 46.6 kg/m2 and a median MELD of 24 underwent a simultaneous liver transplant and sleeve gastrectomy. None of the patients experienced any problems with immunosuppressive medications intake or graft rejection or dysfunction. Two of the patients had a complete remission of hypertension and diabetes. All three are currently alive with normal allograft function.

According to the post-liver transplant group, recent reports support the contention that this unique subgroup of obese post-transplanted patients is suitable for BS. A systemic review by Lazzati et al. [31] determined that BS is feasible and effective in patients after liver transplant. The morbidity rates were higher than the general population undergoing BS, but they remained acceptable (9% versus 5%, respectively) [31, 32]. Lin et al. [19] recently reported nine LSG procedures in patients after liver transplantation and did not observe any significant changes in dosing of tacrolimus or medication trough levels. Technical feasibility should be considered when choosing the type of bariatric procedure. In many studies, the most common procedure has been sleeve gastrectomy, with up to 100% in some series [31, 33, 34].

BS is the most effective solution for morbid obesity, and the number of patients undergoing it is consistently growing [35, 36].

With the most up to date data [37,38,39], strong recommendations cannot be made since most of the studies are case reports, small-sized, with a retrospective design and short mean follow-up, generally less than 5 years. In the light of the limited available data, pre-transplantation BS might be a reasonable approach for obese patients, whereas concomitant/post-transplantation BS might be considered for highly selected patients. The optimal type of BS remains unclear, but sleeve gastrectomy seems to be the preferred approach by most surgeons [28, 33, 34, 40]. As for immunosuppressive therapy after BS in our pharmacokinetic study of transplant recipients, tacrolimus blood levels were maintained at therapeutic range after bariatric surgery [14]. This is most probably explained by tacrolimus extensive enteric absorption, estimated to occurred mainly in the proximal duodenum, however, it was shown in a model of short-bowel piglets that the drug can be absorbed from the colon as well [41, 42]. Comparative data on long-term outcomes regarding optimal timing and type of bariatric procedure are lacking.

References

Zaydfudim V, Feurer ID, Moore DE, Wisawatapnimit P, Wright JK, Wright PC. The negative effect of pretransplant overweight and obesity on the rate of improvement in physical quality of life after liver transplantation. Surgery. 2009;146(2):174–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.027.

Nair S, Cohen DB, Cohen MP, Tan H, Maley W, Thuluvath PJ. Postoperative morbidity, mortality, costs, and long-term survival in severely obese patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(3):842–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03629.x.

Mucha K, Foroncewicz B, Ryter M, et al. Weight gain in renal transplant recipients in a Polish single centre. Ann Transplant. 2015;20:16–20. https://doi.org/10.12659/AOT.892754.

Beckmann S, Drent G, Ruppar T, De Geest S. Weight gain , overweight and obesity in solid organ transplantation — a study protocol for a systematic literature review. Syst Rev. 2015;4(2):1–8.

Richards J, Gunson B, Johnson J, Neuberger J. Weight gain and obesity after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;18(4):461–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00067.x.

Hoogeveen EK, Aalten J, Rothman KJ, Roodnat JI, Mallat MJK, Borm G, et al. Effect of obesity on the outcome of kidney transplantation: a 20-year follow-up. Transplantation. 2011;91(8):869–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e3182100f3a.

Hawn MT, Bian J, Leeth RR, Ritchie G, Allen N, Bland KI, et al. Impact of obesity on resource utilization for general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):821–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000161044.20857.24.

Romero-Corral A, Montori VM, Somers VK, Korinek J, Thomas RJ, Allison TG, et al. Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studies. Lancet. 2006;368(9536):666–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69251-9.

Gore JL, Pham PT, Danovitch GM, Wilkinson AH, Rosenthal JT, Lipshutz GS, et al. Obesity and outcome following renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(2):357–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01198.x.

Aalten J, Christiaans MH, De Fijter H, et al. The influence of obesity on short- and long-term graft and patient survival after renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 2006;19(11):901–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00367.x.

Meier-Kriesche H, Arndorfer J, Kaplan B. The impact of body mass index on renal transplant outcomes: a significant independent risk factor for graft failure and patient death. Transplantation. 2002;73(1):70–4 http://journals.lww.com/transplantjournal/Abstract/2002/01150/THE_IMPACT_OF_BODY_MASS_INDEX_ON_RENAL_TRANSPLANT.13.aspx.

Lynch RJ, Ranney DN, Shijie C, Lee DS, Samala N, Englesbe MJ. Obesity, surgical site infection, and outcome following renal transplantation. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):1014–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4ee9a.

Levin NW, Handelman GJ, Coresh J, Port FK, Kaysen GA. Reverse epidemiology: a confusing, confounding, and inaccurate term. Semin Dial. 2007;20(6):586–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00366.x.

Yemini R, Nesher E, Winkler J, Carmeli I, Azran C, Ben David M, Mor E, Keidar A Bariatric surgery in solid organ transplant patients: long-term follow-up results of outcome, safety, and effect on immunosuppression. Am J Transplant 2018.

Golomb I, Winkler J, Ben-Yakov A, Benitez CC, Keidar A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a weight reduction strategy in obese patients after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(10):2384–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.12829.

Nesher E, Mor E, Shlomai A, et al. Simultaneous liver transplantation and sleeve gastrectomy: prohibitive combination or a necessity? Obes Surg. 2017;27(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2634-5.

Heimbach JK, Watt KDS, Poterucha JJ, Ziller NF, Cecco SD, Charlton MR, et al. Combined liver transplantation and gastric sleeve resection for patients with medically complicated obesity and end-stage liver disease. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(2):363–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04318.x.

Tichansky DS, Madan AK. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is safe and feasible after orthotopic liver transplantation. Obes Surg. 2005;15(10):1481–6. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089205774859164.

Lin MYC, Tavakol MM, Sarin A, Amirkiai SM, Rogers SJ, Carter JT, et al. Safety and feasibility of sleeve gastrectomy in morbidly obese patients following liver transplantation. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2013;27(1):81–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2410-5.

Acosta A, Streett S, Kroh MD, et al. White paper AGA: POWER — practice guide on obesity and weight management, education, and resources. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):631–49.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.023.

Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28431.

Adams LA, Lymp JF, St. Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):113–21. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014.

Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(7):434–8 http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/7382552%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7382552%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7382552.

Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, Hammar U, Stål P, Hultcrantz R, et al. Risk for development of severe liver disease in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a long-term follow-up study. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2(1):48–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1124.

Younossi Z, Stepanova M, Ong JP, Jacobson IM, Bugianesi E, Duseja A, et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is the fastest growing cause of hepatocellular carcinoma in liver transplant candidates. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.057.

Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547–55. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039.

Takata MC, Campos GM, Ciovica R, Rabl C, Rogers SJ, Cello JP, et al. Laparoscopic bariatric surgery improves candidacy in morbidly obese patients awaiting transplantation. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(2):159–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2007.12.009.

Wu R, Ortiz J, Dallal R. Is bariatric surgery safe in cirrhotics? Hepat Mon. 2013;13(2):3–5. https://doi.org/10.5812/hepatmon.8536.

Csikesz NG, Nguyen LN, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Nationwide volume and mortality after elective surgery in cirrhotic patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(1):96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.006.

Campsen J, Zimmerman M, Shoen J, Wachs M, Bak T, Mandell MS, et al. Adjustable gastric banding in a morbidly obese patient during liver transplantation. Obes Surg. 2008;18(12):1625–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9633-5.

Lazzati A, Iannelli A, Schneck A, Nelson AC, Katsahian S, Gugenheim J. Bariatric surgery and liver transplantation : a systematic review a new frontier for bariatric surgery 2015:134–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1430-8, 25.

Sarkhosh K, Birch DW, Sharma A, Karmali S. Complications associated with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: a surgeon’s guide. Can J Surg. 2013;56(5):347–52. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.033511.

Osseis M, Lazzati A, Salloum C, Gavara CG, Compagnon P, Feray C, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy after liver transplantation: feasibility and outcomes. Obes Surg. 2018;28(1):242–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2843-y.

Shimizu H, Phuong V, Maia M, Kroh M, Chand B, Schauer PR, et al. Bariatric surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.07.021.

Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Pothier CE, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1567–76. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1200225.

Sjöström L, Lindroos A-K, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683–93. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035622.

Suraweera D, Dutson E, Saab S. Liver transplantation and bariatric surgery: best approach. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21(2):215–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2016.12.001.

Tsochatzis E, Coilly A, Nadalin S, et al. International Liver Transplantation Consensus Statement on End-Stage Liver Disease Due to Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Liver Transplantation.; 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002433, International Liver Transplantation Consensus Statement on end-stage liver disease due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver transplantation.

Diwan T, Heimbac J, Schauer D. Liver transplantation and bariatric surgery: timing and outcomes. Liver Transplant. 2018:1–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.201.

Zamora-Valdes D, Watt KD, Kellogg TA, Poterucha JJ, di Cecco SR, Francisco-Ziller NM, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients undergoing simultaneous liver transplantation and sleeve gastrectomy. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):485–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29848.

Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x.

Nishi K, Ishii T, Wada M, et al. The colon displays an absorptive capacity of tacrolimus. In: Transplantation Proceedings.Vol 36.; 2004:364–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.12.013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yemini, R., Keidar, A., Nesher, E. et al. Commentary: Peri-Transplant Bariatric Surgery. Curr Transpl Rep 5, 365–368 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-018-0220-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-018-0220-y