Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review examines how research focused on treatment for opioid use in perinatal populations and preventive interventions for postpartum psychopathology have remained separate, despite significant overlap.

Recent Findings

Guidelines for best practice in caring for pregnant women with opioid use disorder suggest the use of medication-assisted treatment with additional comprehensive care, including behavioral and mental health interventions. However, intervention research often mutually excludes these two populations, with studies of behavioral interventions for opioid use excluding women with psychopathology and research on preventive interventions for postpartum psychopathology excluding women who are substance using.

Summary

There is a limited evidence-base to inform the selection of appropriate preventive interventions for pregnant women with opioid use disorder that can address opioid use and/or treatment adherence and concurrent mental health risks. We argue that it is critical to integrate research on pregnant women who are opioid using and preventive perinatal mental health interventions to catalyze pivotal change in how we address the opioid epidemic within this growing population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The devastating consequences of the opioid epidemic in the USA has been alarmingly documented in terms of the very high prevalence of opioid misuse, reaching 11.8 million adults in 2016 [1], and number of overdose deaths, estimated at 42,000 in 2016 [2]. Of utmost concern, the group with the greatest rise in opioid misuse includes women of childbearing age [3]. The consequences of opioid use disorder (OUD) [4] are more severe for women than men, including shorter length from opioid initiation to dependence (telescoping) [5, 6], more intense cravings [7], and greater resultant impairment [8, 9]. Risk factors for opioid misuse may not be equally weighted in men and women, with risk factors for women being more strongly linked to psychological distress [10, 11], interpersonal violence [12, 13], and childhood interpersonal trauma [10, 11, 14].

Particularly alarming is the impact of the opioid epidemic upon the next generation, highlighted by the increasing rate of pregnant women with OUD. From 1994 to 2014, the rate of women with OUD at the time of delivery increased 333% [15]. Opioid use during pregnancy can have substantial impact on mothers and infants, including neonatal opioid withdrawal (NOW), pregnancy and labor complications, and maternal death [16, 17]. Further, there are high rates of opioid misuse among young parents [18] and large numbers of children are estimated to live in families with a parent with OUD [19••]. Parental substance use significantly increases the likelihood of child maltreatment [20], child welfare involvement [21, 22], and poor behavioral and health outcomes for children [23, 24] .

Current research is heavily weighted towards neonatal, child, and birth/delivery outcomes, which are of critical importance. However, much less consideration has been placed on the impact of opioid use during pregnancy and postpartum on maternal mental health and well-being—constructs inexorably intertwined with infant outcomes and the intergenerational transmission of the effects of opioid use. We argue that a stronger focus on maternal mental health, specifically among pregnant women who are currently opioid using or receiving treatment for OUD (e.g., medication-assisted treatment; MAT) is a crucial component for addressing the opioid epidemic within this growing, but drastically under examined, population. The recent emphasis on maternal mental health during pregnancy and postpartum with regard to clinical guidelines [25•] and pharmaceuticals (e.g., brexanolone) [26] makes this an opportune moment to emphasize the importance of incorporating women who are opioid using into this growing movement towards greater maternal well-being during the prenatal and postpartum periods.

Relevance of Prenatal and Postpartum Neuroplasticity for Opioid Use and Mental Health

The prenatal and postpartum periods are times of heightened neuroplasticity, including volumetric and neurochemical changes in medial prefrontal, sub-cortical, and sensory brain regions [27•, 28,29,30,31]. Postpartum women demonstrate increased activation of brain regions implicated in reward circuitry, including ventral striatal (e.g., nucleus accumbens) and medial prefrontal brain regions, to images of their own infants [29, 31] and enhanced activation of brain regions involved in stress responding, such as the amygdala [27•, 28, 29, 31,32,33,34]. Stress reactivity peaks in the early postpartum period (4 to 6 weeks) [35, 36] and then gradually diminishes over the first 3 to 4 months after birth [36]. Neuroplasticity in reward and motivation circuits and stress reactivity during the postpartum period is thought to promote greater maternal responding [29,30,31, 37, 38] and responsive parenting behaviors [32, 39,40,41].

Brain regions implicated in maternal responding, specifically reward processing and stress reactivity, are also implicated in the neurocircuitry of addiction [42,43,44]. This overlap has led to a proposed reward-stress dysregulation model of maternal responding whereby the reward salience of infant related cues is decreased and stress reactivity to infant related cues is increased among postpartum women with addiction, leading to poorer maternal responding and less responsive parenting behaviors [44, 45]. Evidence in support of the reward-stress dysregulation model of maternal responding includes lower levels of engagement with infants [43] and dampened activation of reward circuitry, implicated in addiction, to infant stimuli among mothers using substances [46, 47]. In the context of the model, these findings have been interpreted as evidence of decreased reward sensitivity [48••] because infant stimuli consistently elicit activation of reward circuitry in postpartum women [29, 31].

Interestingly, reward processing and stress reactivity are also implicated in postpartum psychiatric disorders, particularly postpartum depression (PPD). Similar to postpartum women who are substance using, women with PPD demonstrate dampened brain activation of reward and motivation circuits to images of their own infants [49]. Additionally, they demonstrate decreased activation of prefrontal regions (e.g., medial prefrontal cortex) implicated in stress reactivity [50] to distress cues from their own infants [51]. Findings related to amygdala activation have been mixed, with some studies finding increased activation and others decreased activation in women with PPD [27•]. There is likely a U-shaped function for normative changes to amygdala activation during the postpartum period, with increased activation normative at certain periods (earlier postpartum) and decreased activation at others (later postpartum) [27•]. Therefore, altered activation of sub-cortical stress response regions may be dependent on the specific postpartum time period. In addition to altered functional recruitment of brain regions involved in stress responding, there is also altered functional connectivity within and between brain regions implicated in stress reactivity in women with PPD [52•]. The apparent overlap in the neural circuitry related to maternal substance use, including opioids, and PPD highlights the need to address these problems as interrelated from both a research and clinical perspective.

Limited Integration of Traditional Treatment for OUD During Pregnancy and Mental Health Treatment

The best practice guidelines recommend the use of MAT for treating pregnant individuals with OUD [53, 54••, 55]. Guidelines for MAT during pregnancy specify the use of methadone and, more recently, buprenorphine [53, 56]. Both medications have agonistic effects on opioid receptors and are FDA-approved for the prevention of opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms among adults with OUD [57]. Among pregnant individuals, numerous health outcome studies have found methadone and buprenorphine to be effective and safe (for review, see [54••, 58]) when administered daily on a flexible dose schedule (i.e., 4–16 mg/day for buprenorphine or 60–120 mg/day for methadone) within a comprehensive care model [53]. Overall, both methadone and buprenorphine have been shown to be safer alternatives for infants than continued opioid use or medically supervised withdrawal [56].

Neonatal and maternal outcomes at or near the time of delivery are the primary health outcomes used to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of MAT during pregnancy. Neonatal outcomes typically include gestational age at birth, birth weight and length, head circumference, pre-term birth rates, NOW characteristics, and length of hospital/NICU stay [58,59,60,61]. When included, maternal outcomes are often secondary and focused on mode of delivery (e.g., Cesarean section vs. vaginal), use of anesthetics during delivery, drug use at time of delivery, MAT dosage at time of delivery, decision to breastfeed, and treatment retention [59,60,61]. A recent literature review conducted to inform national guidelines concluded methadone and buprenorphine to be effective when administered in the context of comprehensive care [54••]; however, no maternal outcomes related to mental health or well-being were reported.

In addition to pharmacotherapy, best practice MAT guidelines for pregnancy recommend comprehensive care that includes adjunctive behavioral and mental health interventions [53, 56, 62]. Adjunctive behavioral interventions for OUD often address underlying processes that support continued opioid use and maintenance of pharmacotherapy, with some interventions also addressing mental health difficulties that sustain substance use [63, 64]. The behavioral interventions with the greatest support in reducing opioid use, increasing adherence to pharmacotherapy, and harm reduction in non-pregnant [63, 65] and pregnant [66] populations are contingency management (CM) and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), which can include motivational interviewing (MI) techniques. There is growing evidence that behavioral interventions during pregnancy, as an adjunct to MAT, can also increase engagement in prenatal care [66, 67]. However, less than 40% of pregnant women receiving opioid pharmacotherapy had claims for behavioral health services in a recent trend analysis [62].

The recommended inclusion of not just behavioral interventions to support treatment retention and reduced substance use but also mental health interventions is of critical importance because of the high comorbidity in rates of opioid use and psychiatric disorders [68, 69]. Further, the presence of a psychiatric disorder significantly increases the rate of illicit substance use [68, 69], including specifically in populations of adults seeking MAT for OUD [70]. In women, comorbidity of OUD with mood and anxiety disorders is significantly more pronounced than men [69,70,71]. Psychiatric disorders overall occur at significantly higher rates among women than men using illicit substances [69].

Similar to research on MAT, outcomes for behavioral interventions for opioid use during pregnancy have traditionally focused on physical neonatal characteristics, NOW symptoms, delivery outcomes, treatment engagement, and substance use [66], with limited inclusion of maternal mental health outcomes. The limited research available suggests that behavioral interventions for OUD during pregnancy have the potential to reduce depressive symptoms postpartum [67]. However, psychiatric symptoms may be a barrier to pregnant women seeking MAT during pregnancy. For example, women who seek MAT for OUD during pregnancy and have higher levels of depression are more likely to withdraw from treatment than women with lower levels of depression [67]. On the other hand, up to 50% of RCTs for behavioral interventions for OUD during pregnancy exclude women with psychiatric disorders, symptoms, or distress, or who are suicidal [66]. Therefore, we have limited evidence speaking to the effectiveness of behavioral interventions for pregnant women with co-morbid OUD and psychiatric disorders or the impact of behavioral interventions during pregnancy for OUD on mental health outcomes.

Preventive Interventions for Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders Do Not Sufficiently Include Pregnant Women with OUD

Over the past decade, greater emphasis has been placed on the importance of prenatal and postpartum mental health due to our growing knowledge of the effects of prenatal and postpartum psychiatric disorders on women and their infants [52, 72, 73]. PPD is the condition that has received the greatest attention. In particular, the need for preventive interventions to reduce risk of PPD as opposed to responsive interventions once PPD symptoms onset has been increasingly recognized. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [25•] recently recommended all pregnant and postpartum women at-risk for prenatal or postpartum depression be referred for psychosocial intervention [25•]. Despite the urgent need for such preventive interventions, few have been validated with high quality studies and the pooled effect size of the interventions in higher quality studies is small [72•].

The increasing recognition of the importance of early identification of risk and preventive interventions for mental health disorders during pregnancy and postpartum suggests an opportunity to highlight and address maternal OUD from a similar perspective. However, interventions addressing maternal mental health in this early critical period have continued to be developed and validated separately from approaches to address maternal OUD or other forms of substance use. We argue that the continued separate development of these lines of research, and subsequently practice and policy, is detrimental to families in the greatest need. For example, the review of preventive interventions for PPD conducted by the USPSTF found that of the 17 studies deemed high quality RCTs, more than 50% excluded pregnant women who were using substances [72•]. Exclusion criteria adopted in psychosocial studies of both preventive interventions for opioid use and postpartum psychopathology perpetuate differentiating treatment for opioid use and risk for postpartum psychopathology in pregnant women, as opposed to integrating and/or augmenting these two critical needs for highly at-risk women and their infants.

Commentary and Future Directions

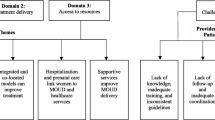

While best practice guidelines [53, 56] speak strongly to the need to augment current MAT for OUD during pregnancy with comprehensive care that includes behavioral interventions and mental health intervention, significant gaps in research place programs and institutions in the position of needing to make decisions about intervention implementation without a sufficient evidence-base that allows them to maximize both efficacious and efficient intervention delivery. This gap is fueled by a lack of evidence for whether existing interventions for maternal mental health could be effective for pregnant women with OUD in improving mental health and reducing future opioid use and evidence regarding how existing adjunctive behavioral interventions for women with OUD affect mental health. See Fig. 1. Multiple avenues of research have strong potential to increase evidence-based interventions targeting both opioid use and mental health as well as inform the development of policy supporting the comprehensive treatment of pregnant women with OUD.

Prevailing separate lines of research into opioid use and other psychiatric conditions during pregnancy versus an integrated approach. Prevailing approaches contribute to parallel lines of research into opioid use disorder (OUD) versus other psychiatric conditions and risk factors during pregnancy, missing the critical intersection. An integrated approach to both basic and intervention research has potential to advance understanding of the overlap and reciprocal connections between OUD, existing psychiatric conditions, and risk factors for postpartum psychiatric conditions (e.g., history of depression and trauma). Such an approach also draws attention to important questions regarding how treatments for psychiatric conditions during pregnancy (psychotherapy and psychotropic medications) may work for women with OUD, and/or interact with treatments targeting OUD (e.g., medication-assisted treatment (MAT)). Finally, the integrated approach lends towards conceptualizing outcomes at multiple levels and considering associations between them

At the most basic level, we have limited knowledge of the trajectory of mental health symptoms across pregnancy and postpartum in both women with and without OUD. Some studies have demonstrated a typical trajectory of depressive symptoms, across populations from different countries, with depressive symptoms typically increasing in the third trimester, peaking around 4 to 6 weeks postpartum, and then decreasing [52•, 74,75,76,77]. However, trajectories of mental health symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with OUD have not been systematically studied. Prior research indicates that risk factors commonly co-occurring with OUD, such as a prior history of psychiatric disorders, trauma history, and prenatal stress, may significantly alter trajectories for prenatal and postpartum psychopathology [52•, 73]. Advancing our understanding of trajectories of mental health symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum among women with OUD has potential to reveal periods of heightened vulnerability, but also to shed light on times of particularly rapid change in symptomatology and other aspects of clinical presentation. Periods of rapid change would be suggestive of heightened plasticity, and thus potential opportunity for increased responsivity to intervention.

Another important direction for future research involves increasing our understanding of heterogeneity among pregnant and postpartum women with OUD. There has been a growing recognition of the importance of increasing our understanding of heterogeneity in psychiatry and other health disciplines, including unique etiologies and treatment needs despite similar behavioral or psychiatric presentations, as well as the occurrence of multiple symptom clusters or disorders within an individual [78]. Research addressing heterogeneity among pregnant and postpartum women with OUD, particularly considering co-occurring mental health symptoms, underlying cognitive phenotypes, and neurobiological functioning, will be critical for advancing our understanding of pathways of risk and resilience. Given the prevalence of comorbidity between OUD and psychiatric symptoms/disorders, there will likely be overlapping and distinct pathways contributing to the development of OUD and mental health difficulties. Further, identification of subgroups among women with OUD may reveal unique combinations of environmental risk factors, trauma history, cognitive and emotional regulation skills, stress reactivity, and reward processing, which have significant implications for targeting intervention.

Intervention research can both benefit from and drive forward these avenues of more basic research to advance understanding of the unique opportunities and challenges of pregnancy and the postpartum period among women with OUD. Intervention research, and particularly involving randomization of individuals to conditions (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT]), can shed light on mechanisms underlying positive or negative forms of adaptation for mothers during these periods. This is particularly true of intervention research including in-depth characterization of cognitive, emotional, and reward processing, and examining neurobiological indicators. While outcome markers may be detectable by behavioral measures (e.g., cognitive, affective, functioning) or clinical measures (e.g., symptoms, disorders), neurobiological markers of treatment response may provide a unique window for examining aspects of treatment response critical for driving change in behavior and clinical symptomatology. Adaptive intervention designs, such as sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trials (SMART) [79], which allow for several decision points and tailoring based on individual responding (or nonresponding) will likely be particularly important for advancing our understanding of intervention efficacy and mechanisms of change [24••]. Such an approach would allow for testing varying levels and types of interventions to best support individuals within the heterogeneous population of women with OUD during pregnancy and postpartum.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need to better understand and support pregnant and postpartum women with OUD. Weaving together basic research, intervention and implementation science will be necessary to provide a more solid foundation of knowledge upon which to build efforts in this area. Targeting resources towards this population holds promise for supporting mothers and infants, and preventing intergenerational transmission of the negative sequelae of the current opioid epidemic.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

McCrane-Katz EF. SAMHSA/HHS: an update on the opioid crisis. 2018.

Prevention CDC. 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/features/confronting-opioids/index.html. Accessed 3 August 2018.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7):821–6.

Silverman ME, Loudon H, Safier M, Protopopescu X, Leiter G, Liu X, et al. Neural dysfunction in postpartum depression: an fMRI pilot study. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(11):853–62.

Hernandez-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(3):265–72.

Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(1):1–21.

Back SE, Lawson KM, Singleton LM, Brady KT. Characteristics and correlates of men and women with prescription opioid dependence. Addict Behav. 2011;36(8):829–34.

McHugh RK, Devito EE, Dodd D, Carroll KM, Potter JS, Greenfield SF, et al. Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;45(1):38–43.

McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Barlow DH, Fitzmaurice GM, Greenfield SF, Weiss RD. Development of an integrated cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and opioid use disorder: study protocol and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;60:105–12.

Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432–42.

Jamison RN, Ross EL, Michna E, Chen LQ, Holcomb C, Wasan AD. Substance misuse treatment for high-risk chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2010;150(3):390–400.

Resnick HS, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG. Health impact of interpersonal violence 2: medical and mental health outcomes. Behav Med. 1997;23(2):65–78.

Liebschutz J, Savetsky JB, Saitz R, Horton NJ, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH. The relationship between sexual and physical abuse and substance abuse consequences. J Sub Abuse Treat. 2002;22(3):121–8.

Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):953–9.

Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999-2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845–9.

Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, Creanga AA, Leffert LR. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(6):1158–65.

Patrick SW, Dudley J, Martin PR, Harrell FE, Warren MD, Hartmann KE, et al. Prescription opioid epidemic and infant outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):842–50.

Austin AE, Shanahan ME. Prescription opioid use among young parents in the United States: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Pain Med. 2017;18(12):2361–8.

•• Peisch VD, Sullivan A, Breslend NL, Benoit R, Sigmon SC, Forehand GL, et al. Parental opioid abuse: A review of child outcomes, parenting, and parenting interventions. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(7):2082–99 Comprehensive review of the impact of parental opioid use on parenting, which is one of the mechanisms that may facilitate the intergenerational transmission of the effects of opioid use.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. Child maltreatment. 2016.

Dubowitz H, Kim J, Black MM, Weisbart C, Semiatin J, Magder LS. Identifying children at high risk for a child maltreatment report. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(2):96–104.

Barth RP, Gibbons C, Guo S. Substance abuse treatment and the recurrence of maltreatment among caregivers with children living at home: a propensity score analysis. J Subst Abus Treat. 2006;30(2):93–104.

Bountress K, Chassin L. Risk for behavior problems in children of parents with substance use disorders. Amer J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(3):275–86.

•• Cioffi CC, Leve LD, Seeley JR. Accelerating the pace of science: improving parenting practices in parents with opioid use disorder. Parenting. 2019;19(3):244–66 Critical development of an adaptive and hybrid approach for the development and implementation of interventions for parents who are opioid using.

• US Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation: Interventions to prevent perinatal depression. JAMA. 2019;321(6):580–7 Recent guidelines for the screening of women at risk for perinatal depression and subsequent recommendation for referral to therapuetic intervention.

Powell JG, Garland S, Preston K, Piszczatoski C. Brexanolone (Zulresso): finally, an FDA-approved treatment for postpartum depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;54(2):157–63 1060028019873320.

• Barba-Müller E, Craddock S, Carmona S, Hoekzema E. Brain plasticity in pregnancy and the postpartum period: links to maternal caregiving and mental health. Arch Wom Ment Health. 2019;22(2):289–99 Comprehensive review of structural and functional perinatal neuroplasticity and implications for both maternal responding and perinatal psychopathology.

Carmona S, Martínez-García M, Paternina-Die M, Barba-Müller E, Wierenga LM, Alemán-Gómez Y, et al. Pregnancy and adolescence entail similar neuroanatomical adaptations: a comparative analysis of cerebral morphometric changes. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(7):2143–52.

Kim P, Strathearn L, Swain JE. The maternal brain and its plasticity in humans. Horm Behav. 2016;77:113–23.

Moses-Kolko EL, Horner MS, Phillips ML, Hipwell AE, Swain JE. In search of neural endophenotypes of postpartum psychopathology and disrupted maternal caregiving. J Neuroendocrinol. 2014;26(10):665–84.

Swain JE, Kim P, Spicer J, Ho SS, Dayton CJ, Elmadih A, et al. Approaching the biology of human parental attachment: brain imaging, oxytocin and coordinated assessments of mothers and fathers. Brain Res. 2014;1580:78–101.

Barrett J, Wonch KE, Gonzalez A, Ali N, Steiner M, Hall GB, et al. Maternal affect and quality of parenting experiences are related to amygdala response to infant faces. Soc Neurosci. 2012;7(3):252–68.

Lorberbaum JP, Newman JD, Horwitz AR, Dubno JR, Lydiard RB, Hamner MB, et al. A potential role for thalamocingulate circuitry in human maternal behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(6):431–45.

Swain JE, Tasgin E, Mayes LC, Feldman R, Constable RT, Leckman JF. Maternal brain response to own baby-cry is affected by cesarean section delivery. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(10):1042–52.

Gingnell M, Bannbers E, Moes H, Engman J, Sylven S, Skalkidou A, et al. Emotion reactivity is increased 4-6 weeks postpartum in healthy women: a longitudinal fMRI study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128964.

Swain JE, Leckman JF, Mayes LC, Feldman R, Schultz R. Own baby pictures induce parental brain activations according to psychology, experience and postpartum timing. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:126s.

Strathearn L, Fonagy P, Amico J, Montague PR. Adult attachment predicts maternal brain and oxytocin response to infant cues. Neuropsychopharm. 2009;34(13):2655–66.

Strathearn L, Li J, Fonagy P, Montague PR. What's in a smile? Maternal brain responses to infant facial cues. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):40–51.

Kim P, Feldman R, Mayes LC, Eicher V, Thompson N, Leckman JF, et al. Breastfeeding, brain activation to own infant cry, and maternal sensitivity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(8):907–15.

Musser ED, Kaiser-Laurent H, Ablow JC. The neural correlates of maternal sensitivity: an fMRI study. Develop Cog Neurosci. 2012;2(4):428–36.

Numan M. Motivational systems and the neural circuitry of maternal behavior in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49(1):12–21.

Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharm. 2010;35(1):217–38.

Rutherford HJV, Maupin AN, Landi N, Potenza MN, Mayes LC. Current tobacco-smoking and neural responses to infant cues in mothers. Parenting. 2017;17(1):1–10.

Rutherford HJ, Williams SK, Moy S, Mayes LC, Johns JM. Disruption of maternal parenting circuitry by addictive process: rewiring of reward and stress systems. Front Psychol. 2011;2:37.

Strathearn L, Mayes LC. Cocaine addiction in mothers: potential effects on maternal care and infant development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:172–83.

Landi N, Montoya J, Kober H, Rutherford HJ, Mencl WE, Worhunsky PD, et al. Maternal neural responses to infant cries and faces: relationships with substance use. Front Psychol. 2011;2:32.

Kim P, Capistrano CG, Erhart A, Gray-Schiff R, Xu N. Socioeconomic disadvantage, neural responses to infant emotions, and emotional availability among first-time new mothers. Behav Brain Res. 2017;325(Pt B):188–96.

•• Rutherford HJV, Mayes LC. Parenting and addiction: neurobiological insights. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;15:55–60 Comprehensive review and discussion of the reward-stress dysregulation model and how changes to the reward and stress reactivity circuits influences parenting in the context of substance use disorders.

Laurent HK, Ablow JC. A face a mother could love: depression-related maternal neural responses to infant emotion faces. Soc Neurosci. 2013;8(3):228–39.

Ochsner KN, Silvers JA, Buhle JT. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1251(1):E1–E24.

Laurent HK, Ablow JC. A cry in the dark: depressed mothers show reduced neural activation to their own infant’s cry. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;7(2):125–34.

• Pawluski JL, Lonstein JS, Fleming AS. The neurobiology of postpartum anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40(2):106–20 Review of neuroscience research examining neurobiological disruptions associated with postpartum psychopathology, including both a robust body of animal models and a growing body of human neuroimaging work.

Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–67.

•• Klaman SL, Isaacs K, Leopold A, Perpich J, Hayashi S, Vender J, et al. Treating women who are pregnant and parenting for opioid use disorder and the concurrent care of their infants and children: Literature review to support national guidance. J Addict Med. 2017;11(3):178–90 Evidence supporting best practice guidelines for treating women with opioid use disorder, including suggestions for medication-assisted treatment with comprehensive care.

SAMHSA Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorders and their infants. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. 2017.

Thomas CP, Fullerton CA, Kim M, Montejano L, Lyman DR, Dougherty RH, et al. Medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):158–70.

Lund IO, Fischer G, Welle-Strand GK, O'Grady KE, Debelak K, Morrone WR, et al. A comparison of buprenorphine + naloxone to buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Subst Abus. 2013;7:61–74.

Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, Coyle MG, Arria AM, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. New Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320–31.

Lacroix I, Berrebi A, Garipuy D, Schmitt L, Hammou Y, Chaumerliac C, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone in pregnant opioid-dependent women: a prospective multicenter study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(10):1053–9.

Meyer M, Benvenuto A, Howard D, Johnston A, Plante D, Metayer J, et al. Development of a substance abuse program for opioid-dependent nonurban pregnant women improves outcome. J Addict Med. 2012;6(2):124–30.

Krans EE, Kim JY, James AE 3rd, Kelley D, Jarlenski MP. Medication-assisted treatment use among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(5):943–51.

Dugosh K, Abraham A, Seymour B, McLoyd K, Chalk M, Festinger D. A systematic review on the use of psychosocial interventions in conjunction with medications for the treatment of opioid addiction. J Addict Med. 2016;10(2):93–103.

Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–87.

Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):Cd004147.

Terplan M, Ramanadhan S, Locke A, Longinaker N, Lui S. Psychosocial interventions for pregnant women in outpatient illicit drug treatment programs compared to other interventions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(4):CD006037-CD.

Cochran G, Field C, Karp J, Seybert AL, Chen Q, Ringwald W, et al. A community pharmacy intervention for opioid medication misuse: A pilot randomized clinical trial. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(4):395–403.

Crane D, Marcotte M, Applegate M, Massatti R, Hurst M, Menegay M, et al. A statewide quality improvement (QI) initiative for better health outcomes and family stability among pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD) and their infants. J Subst Abus Treat. 2019;102:53–9.

Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–57.

Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW Jr, Bigelow GE. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. JAMA Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71–80.

Grella CE, Needell B, Shi Y, Hser Y-I. Do drug treatment services predict reunification outcomes of mothers and their children in child welfare? J Sub Abuse Treat. 2009;36(3):278–93.

• O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, Coppola E, Gaynes BN. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;321(6):588–601 Identifies high-quality clinical trials examining the efficacy of preventive interventions for postpartum depression, with half of the studies excluding women with significant substance use.

Paschetta E, Berrisford G, Coccia F, Whitmore J, Wood AG, Pretlove S, et al. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: An overview. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(6):501–9.e6.

Dikmen-Yildiz P, Ayers S, Phillips L. Depression, anxiety, PTSD and comorbidity in perinatal women in Turkey: a longitudinal population-based study. Midwifery. 2017;55:29–37.

Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh depression scale (EDDS). J Reproduct Infant Psychol. 1990;8(2):99–107.

Navodani T, Gartland D, Brown SJ, Riggs E, Yelland J. Common maternal health problems among Australian-born and migrant women: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211685.

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–83.

Feczko E, Miranda-Dominguez O, Marr M, Graham AM, Nigg JT, Fair DA. The heterogeneity problem: approaches to identify psychiatric subtypes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23(7):584–601.

Lei H, Nahum-Shani I, Lynch K, Oslin D, Murphy SA. A "SMART" design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:21–48.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ray Anthony for their assistance.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K24AA026876-01, PI: SFE; 1R01DA044778-01A1, MPIs: SFE, ACW; 1P50DA048756-01, MPIs: PAP, Leve, Stormshak).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Opioids

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mackiewicz Seghete, K.L., Graham, A.M., Shank, T.M. et al. Advancing Preventive Interventions for Pregnant Women Who Are Opioid Using via the Integration of Addiction and Mental Health Research. Curr Addict Rep 7, 61–67 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00296-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00296-x