Abstract

Purpose of Review

To conduct a systematic review of recent case-control studies investigating the similarities and differences between gambling disorder (GD), substance use disorders (SUDs), and behavioral addictions (BAs).

Recent Findings

A total of 36 studies were identified for synthesis, with 56% comparing GD to SUDs, 36.11% comparing GD to other BAs, and 8.33% comparing to both. The results indicated that GD and SUDs/BAs do not present with overall differences in neurocognitive, clinical, and impulsivity dimensions. Rather, GD is associated with more nuanced differences in these dimensions. In contrast, GD was likely to present with significant differences in personality although with conflicting results in the directionality and dimensions of the personality trait compared to SUDs/BAs.

Summary

GD warrants classification as a disorder due to addictive behaviors. However, nuanced differences exist between GD and SUDs/BAs, which should be taken into account in the conceptualization of GD as an addiction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gambling disorder (GD) was the first behavioral addiction to be classified in the substance and other related disorders section of the 5th edition of the Diagnostics and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1]. Similarly, the 11th and latest edition of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases classified GD as a disorder due to addictive behaviors (ICD-11) [2]. The re-classification of GD from an impulse control disorder to an addictive disorder occurred due to decades of empirical evidence suggesting that GD shares considerable etiological, clinical, and neurological similarities to substance use disorders (SUDs) [3]. Unfortunately, however, our current understanding of GD as an addiction has largely consisted of observations of their similarities (i.e., relative to non-GD and non-SUD populations) rather than direct comparisons (i.e., case-control studies) [4, 5], which limits our understanding of the similarities between GD and SUDs. Furthermore, there are likely nuanced differences between GD and SUDs, which case-control studies may help to elucidate. For example, previous case-control studies (albeit limited) have found similarities and differences between GD and SUDs/BAs on personality/impulsivity [6,7,8,9,10], craving [7, 8], clinical [11, 12], and neurological dimensions [13].

The aim of the present review was to synthesize the recent literature of case-control studies that have directly compared GD with SUDs on personality, clinical, and neurological dimensions to examine whether GD fits under the classification of a disorder due to addictive behaviors in the ICD-11. Furthermore, elucidating the similarities as well as the differences of GD and SUDs may help to provide a more complete understanding and conceptualization of GD as an addictive disorder. In addition to GD, gaming disorder was also classified as an addiction in the ICD-11 [2]. Given the increasing relevance of behavioral addictions (BAs) including gaming disorder, we aimed to identify empirical studies that compared GD, to other emerging BAs to expand our understanding of BAs as potential addictive disorders. Case-control studies comparing GD to binge eating (BE) were also included given the similarities and conceptualization of BE to addictions [14, 15].

Methods

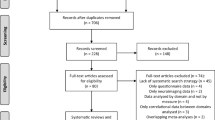

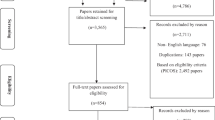

A systematic search of the literature was completed in September 2018 (see Supplemental Materials for the search strategy). Articles were included for synthesis if they met the following criteria: (1) case-control studies comparing GD to SUDs or BAs on personality, clinical, or neurological dimensions, (2) studies published between 2013 and 2018, and (3) studies published in English. Articles were excluded if (1) they were editorials, commentaries, or reviews (references were reviewed for relevancy) and (2) were written in a language other than English.

The search strategy identified 1036 unique articles with 104 articles undergoing full-text review by two independent reviewers. The inter-rater agreement between the two reviewers was high, K = 0.88. Any disagreements during the full-text review were resolved through consensus with the two independent reviewers and the first author. A total of 36 articles were included for synthesis (Fig. 1).

Results

Of the 36 articles, 20 studies compared GD to SUDs, 13 with BAs and three compared GD to both. The majority of the studies consisted of treatment seeking samples (31; 86.11%) were conducted outside of North America (30; 83.33%) and also included control participants (30; 83.33%) (see Table 1 for the detailed sample characteristics). In regard to dimensions, 17 studies compared GD to SUDs and BAs on neurocognitive dimensions, seven on personality dimensions, and four compared clinical characteristics. Eight studies compared GD to SUDs/BAs on both personality and clinical dimensions. Additionally, 22 studies provided secondary information on clinical characteristics that allowed for synthesis and thus were included in the review. While the majority of studies included a control group, results that directly compared GD to the control group were excluded for clarity. For similar reasons, we did not include the results that compared characteristics of participants with comorbidities (see Table 2 for summary of the findings).

Neurocognitive Dimensions

Similarities and differences were found in regard to neurological correlates between GD and SUDs. Specifically, compared to SUDs, GD was associated with decreased functional connectivity in the corticolimbic reward network [16] and the ventral striatum [17] at rest. However, no differences in functional connectivity were found between GD and SUD in the dorsal caudate [17] and similar overlapping connectivity was found in regions associated with stimulus-outcome learning [16]. GD was associated with greater activity in the right ventral striatum during loss anticipation compared to SUDs [18], as well as during reward anticipation [19]. However, no differences were found between GD and SUD during near miss outcomes [19]. Furthermore, GD and SUDs showed differential responses in only two of eight identified networks associated with loss chasing, with GD being associated with greater engagement of medial frontal executive processing networks, whereas SUD was associated with altered engagement in striate-amygdala motivation network [20].

Two studies compared brain connectivity between GD and BAs, specifically with Internet gaming disorder (IGD) [21•, 22]. GD was associated with increased functional connectivity in cognitive and reward circuits, but did not differ in functional connectivity in the default mode network [21•]. Bae et al. [22], using largely the same sample from their previous study [21•], found that 12 weeks of bupropion significantly reduced the symptoms of GD and IGD. Interestingly, however, while the functional connectivity in the default mode network decreased for both GD and IGD groups, there was an increase in functional connectivity in the cognitive control network for GD, whereas it decreased for the IGD group suggesting differential effects of bupropion in GD compared to IGD.

Six case-control studies examined cognitive functioning, such as impaired learning and decision-making in GD in comparison to SUDs with no overall differences. For example, no differences in decision-making were observed compared to SUDs when using the Iowa Gambling Task [23,24,25,26] or the Wisconsin Card Sort Task [27]. Similar patterns were observed when assessing contingency learning [28] and probabilistic learning [29] with no overall differences between GD and SUDs. Rather, nuanced differences were found between GD and SUDs including in verbal and non-verbal components of working memory [23], ability to learn on subsequent tasks on the IGT [23, 24, 26], and the speed in which learning occurs [28], with GD generally showing smaller deficits compared to SUDs.

Two studies compared GD to binge eating disorder (BED) in neurotransmitter functioning [30•, 31]. GD was associated with decreased serotonin binding in the parieto-occipital cortical regions but increased dopamine and opioid binding potential in the nucleus accumbens compared to BED. Additionally, two studies investigated structural differences of gambling and cocaine use disorder (CUD) with contrasting results [32, 33]. While no differences in microstructural features were found between GD and CUD [32], CUD but not GD was associated with decreased gray matter volume in the prefrontal region [33]. Lastly, two studies examined activation of brain regions in relation to craving when cued by cocaine, gambling, and sad videos among participants with CUD, GD, and healthy controls [34, 35]. It was found that the anterior cingulate cortex/ventromedial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) were activated predominately to cocaine videos in CUD [34]. Additionally, the dorsal mPFC region was most strongly activated for CUD participants when viewing cocaine videos, whereas this same region was most strongly activated for GD participants when viewing gambling related videos [34]. In a more recent study, Ren et al. [35] found that similar networks were activated among CUD, GD, and healthy control participants when viewing cocaine, gambling, and sad videos respectively.

Personality Dimensions

Several dimensions of personality were measured when comparing GD to SUDs and BAs, with the majority of studies [9] assessing impulsivity using both self-report [21•, 25, 27, 33, 36••, 37, 38] and behavioral tasks [24, 25, 38, 39]. Eight studies assessed personality using the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) [27, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46], which measures four temperaments (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence) and three characters (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence). Two studies compared personality dimensions of GD and SUDs using the five-factor model of personality [47, 48].

Overall, no differences were found in self-report measures of impulsivity between GD and SUDs [25, 33, 36••] or BAs [21•, 36••, 37]. When differences were found, GD was associated with lower overall levels of impulsivity compared to SUDs [38], IGD [38], and problematic internet use (PIU) [27]. When examining specific facets of impulsivity, GD was associated with higher scores on the cognitive dimension of impulsivity compared to IGD, yet lower scores on the motor and non-planning component of impulsivity compared to IGD and alcohol use disorder (AUD) [38]. Similar patterns emerged when impulsivity was measured using behavioral paradigms with no overall differences between GD and SUDs. Specifically, GD and AUD did not differ on the stop-signal task [25, 38] or delay discounting [39]. Furthermore, GD and IGD did not differ on the stop-signal task [38]. Conversely, GD was associated with better performance on the go–no-go task compared to PIU [27] and SUDs [24]. In regard to compulsivity, although GD and SUDs did not differ in regard to self-reported levels of compulsivity [24], GD performed worse on behavioral tasks of compulsivity compared to SUDs and BAs [38].

Significant differences in personality profiles were found between GD and SUDs/BAs. However, there was significant variability in the facet of personality that differed, as well as in the directionality of the results. Compared to SUDs, for example, GD was associated with lower levels of harm avoidance, self-transcendence, thoroughness, and openness to experiences [40, 47], but higher in self-directedness and cooperativeness [40]. Similarly, no consistent findings regarding personality dimensions were found when comparing GD to BAs, with significant heterogeneity regarding the directionality and personality dimensions that differed between the two groups [27, 41,42,43,44,45, 48].

Clinical Dimensions

Seven studies compared clinical characteristics of GD to SUDs/BAs, including perception of stigma, trauma, suicidal ideations, coping strategies, attachment, comorbidities, and psychopathology. Regarding self-stigma, although similar across GD, AUD, and SUD, GD participants were less likely to be aware of the stigma associated with their addiction [49]. In regard to trauma and suicidality, GD was associated with similar histories of traumatic exposure and history of suicidal attempts compared to SUDs [50, 51] and PIU [50], while current suicidal ideations were increased in GD compared to SUDs [51]. Similarities in coping strategies were found between GD and PIU, with the exception of GD being less likely to be associated with the use of behavioral and mental disengagement [46]. Furthermore, no differences in attachment or global functioning were found between GD and PIU [46]. Three studies compared GD to BAs on broad dimensions of psychopathology using the Symptom Checklist Revised-90 [52] with mixed results [42,43,44]. While no differences were found in psychopathology between GD and CSB [42], significant differences were found in all domains between GD and CB, with GD being associated with lower levels of psychopathology [43, 45].

Twenty-two studies were synthesized regarding secondary clinical characteristics with the vast majority providing information on comorbid substance and mental health conditions (see Supplemental Table 1). Generally, the results were mixed in regard to comorbid rates of alcohol use in GD compared to SUDs [19, 29, 39, 50]. In regard to BAs and comorbid alcohol use, four studies found no differences [21•, 31, 41, 42] while four studies reported higher rates of alcohol use in GD compared to BAs [43,44,45, 50]. In contrast, the majority of studies found differences in regard to nicotine use, with GD being associated with lower use of nicotine compared to SUDs [18, 20, 23, 50] but higher use compared to BAs [30•, 31, 41,42,43, 45]. Five studies found no differences in regard to nicotine use [19,20,21,22, 39]. Additionally, seven studies provided results of comorbid use of psychoactive substances with inconsistent findings across BAs [41,42,43,44,45, 50] and SUDs [29, 50].

When examining comorbidity of mental health disorders, the majority of studies found no differences between GD and SUDs or BAs in depression [18, 21•, 22, 24, 27, 31, 38, 46], anxiety [24, 38, 46], or other psychiatric disorders, including personality disorders and self-harm [39, 42, 44]. Of the remaining studies, comorbid depression was found to be higher compared to CUD [19], and mixed compared to AUD [28, 38]. GD also presented with lower anxiety compared to AUD [38] and mixed in regard with ADHD compared to IGD [21•, 22]. Other clinical characteristics assessed included age of onset, with GD presenting with later onset than IGD [38, 41] and a similar onset to CB [43, 45]. No differences between GD and SUDs or BAs were found in regard to duration of addiction [19, 20, 29, 43], or years of abstinence [28, 29] and the literature was mixed in regard to addiction severity [41, 49].

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to conduct a systematic review of recent case-control studies comparing GD to other addictive disorders, including SUDs and BAs, to examine whether GD (and other BAs) warrants classification as a disorder due to addictive behaviors in the ICD-11. As our current understanding of GD and SUD consists largely of observations of their similarities, the present review focused on case-control studies to provide a more complete understanding of GD as an addiction. In contrast to the relatively few case-control studies prior to 2013, there were 36 studies comparing GD to other addictions within the last 5 years, including 14 studies comparing GD to other BAs. A significant portion of these studies examined neurocognitive dimensions, specifically functional connectivity, between GD and SUDs/BAs. In contrast, studies examining personality and clinical characteristics between GD and SUDs/BAs were rare.

The results of the systematic review converge with the previous literature and suggest that GD presents with similarities to SUDs in neurocognitive, personality, or clinical dimensions (e.g., comorbidity), thus warranting its inclusion as an addictive disorder in the ICD-11. However, GD also presented with nuanced differences compared to SUDs/BAs, which may have important implications in GDs conceptualization as an addictive disorder. Interestingly, when differences were found in cognitive functioning and impulsivity, GD generally presented with lower deficits in cognitive functioning [23, 24, 28, 41] and lower levels of impulsivity [24, 27, 38]. A potential reason for this finding could be that GD, unlike SUDs, does not involve the ingestion of psychoactive substances, the pharmacokinetics of which are associated with cognitive decline and functioning [53]. Another consistent finding was that GD and SUDs generally did not differ in the rates of comorbid mental health disorders. In contrast, the results were mixed in regard to comorbid alcohol and drug use. For example, significant differences were found in regard to comorbid nicotine, with GD being associated with lower nicotine use compared to SUDs but higher when compared to BAs. Future studies examining mechanisms for these differences as well as social environmental influences would be highly informative.

Significant differences existed between GD and personality traits, specifically in regard to the TCI. However, no clear picture emerged in regard to the differences in GD and SUDs/BAs given the contrasting results in the personality traits, which varied in the directionality of the differences. Similarly, no clear patterns emerged in regard to measures of psychopathology between GD and other addictions. Thus, more studies are needed in this area to provide clarity regarding the similarities and differences between GD and SUDs/BAs on personality and psychopathology. While the main aim of the paper was to examine the similarities and differences between GD and SUDs, we also compared GD to emerging BAs to add to our growing understanding of other potentially addictive behaviors. Similar to the results comparing GD and SUDs, GD generally shared similarities to other BAs, including video gaming, which was recently classified as an addiction in the ICD-11 [2]. However, GD and BAs presented with greater differences compared to GD and SUDs. Thus, more research is needed to determine whether emerging BAs should also be included as disorders due to addictive behaviors.

Taken together, the results of the present review may provide support for the syndrome model of addiction [54], in which addictive disorders are conceptualized as a syndrome with multiple expressions. However, the syndrome model acknowledges that addictive disorders are also likely to present with unique manifestations, such as the nuanced differences found between GD and SUDs/BAs in the present review. Conceptualizing addictions as an underlying disorder may also help with the recent scope creep of BAs, in which more and more everyday behaviors are purported to be “new” psychiatric disorders [55]. The results may also have important treatment implications. Specifically, rather than the creation of single disorder treatments for addictions, it may be more efficient to develop a transdiagnostic treatment to target the underlying similarities (e.g., cognitive function, impulsivity, comorbidity) as was recently proposed in the component model of addiction treatment [56].

A limitation of the present review was the substantial heterogeneity in the studies that were included for synthesis. For example, different measures were used to assess similar constructs (e.g., personality, impulsivity) and there existed differences in sample characteristics, including eight studies that only included males. Relatedly, the majority of the studies were treatment seeking samples, thus reducing the generalizability of our results given less than 10% of people with GD seek treatment [57]. Third, a relatively small proportion of studies (16%) examined clinical characteristics between GD and SUDs/BAs and thus more research is needed in this domain. Lastly, the results of the systematic review maybe biased by the file-drawer effect given the reliance on significance findings in the published literature.

Conclusion

Our understanding of GD as an addiction has largely consisted of its observed similarities to SUDs. This review adds to the growing understanding of GD and other emerging BAs as addictions by synthesizing the recent case-control studies comparing GD to SUDs/BAs. Given the rising relevance of BAs in clinical psychology and psychiatry, further case-control studies comparing GD, SUDs, and BAs will further help with the ongoing conceptualization of addictive disorders, including the conceptualization of emerging BAs.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

DSM 5. DSM 5. Am J Psychiatr 2013. 991

Saunders JB. Substance use and addictive disorders in DSM-5 and ICD 10 and the draft ICD 11. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2017;30:227–37.

Grant JE, Potenza MN, Weinstein A, Gorelick DA. Introduction to behavioral addictions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):233–41.

Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, De Beurs E, Van Den Brink W. Pathological gambling: a comprehensive review of biobehavioral findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:123–41.

Petry NM. Should the scope of addictive behaviors be broadened to include pathological gambling? Addiction. 2006;101:152–60.

Albein-Urios N, Martinez-González JM, Lozano Ó, Clark L, Verdejo-García A. Comparison of impulsivity and working memory in cocaine addiction and pathological gambling: implications for cocaine-induced neurotoxicity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:1–2):1–6.

Tavares H, Zilberman ML, Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N. Comparison of craving between pathological gamblers and alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(8):1427–31.

Castellani B, Rugle L. A comparison of pathological gamblers to alcoholics and cocaine misusers on impulsivity, sensation seeking, and craving. Subst Use Misuse. 1995;30(3):275–89.

Lee HW, Choi J-S, Shin Y-C, Lee J-Y, Jung HY, Kwon JS. Impulsivity in internet addiction: a comparison with pathological gambling. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15(7):373–7.

Ciarrocchi JW, Kirschner NM, Fallik F. Personality dimensions of male pathological gamblers, alcoholics, and dually addicted gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 1991;7(2):133–41.

Orford J, Morison V, Somers M. Drinking and gambling: a comparison with implications for theories of addiction. Drug and Alcohol Review. 1996;15:47–56.

Ciarrocchi J, Hohmann AA. The family environment of married male pathological gamblers, alcoholics, and dually addicted gamblers. J Gambl Behav. 1989;5(4):283–91.

Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, De Beurs E, Van Den Brink W. Neurocognitive functions in pathological gambling: a comparison with alcohol dependence, Tourette syndrome and normal controls. Addiction. 2006;101(4):534–47.

Gearhardt AN, White MA, Potenza MN. Binge eating disorder and food addiction. Curr Drug Abus Rev. 2011;4(3):201–7.

Smith DG, Robbins TW. The neurobiological underpinnings of obesity and binge eating: a rationale for adopting the food addiction model. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:804–10.

Contreras-Rodríguez O, Albein-Urios N, Vilar-López R, Perales JC, Martínez-Gonzalez JM, Fernández-Serrano MJ, et al. Increased corticolimbic connectivity in cocaine dependence versus pathological gambling is associated with drug severity and emotion-related impulsivity. Addict Biol. 2016;21(3):709–18.

Contreras-Rodríguez O, Albein-Urios N, Perales JC, Martínez-Gonzalez JM, Vilar-López R, Fernández-Serrano MJ, et al. Cocaine-specific neuroplasticity in the ventral striatum network is linked to delay discounting and drug relapse. Addiction. 2015;110(12):1953–62.

Romanczuk-Seiferth N, Koehler S, Dreesen C, Wüstenberg T, Heinz A. Pathological gambling and alcohol dependence: neural disturbances in reward and loss avoidance processing. Addict Biol. 2015;20(3):557–69.

Worhunsky PD, Malison RT, Rogers RD, Potenza MN. Altered neural correlates of reward and loss processing during simulated slot-machine fMRI in pathological gambling and cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:77–86.

Worhunsky PD, Potenza MN, Rogers RD. Alterations in functional brain networks associated with loss-chasing in gambling disorder and cocaine-use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:363–71.

• Bae S, Han DH, Jung J, Nam KC, Renshaw PF. Comparison of brain connectivity between Internet gambling disorder and Internet gaming disorder: a preliminary study. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):1–11 One of the only studies to compare functional connectivity between gambling disorder and another behavioral addiction.

Bae S, Hong JS, Kim SM, Han DH. Bupropion shows different effects on brain functional connectivity in patients with internet-based gambling disorder and internet gaming disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9(APR).

Sen YW, Li YH, Xiao L, Zhu N, Bechara A, Sui N. Working memory and affective decision-making in addiction: a neurocognitive comparison between heroin addicts, pathological gamblers and healthy controls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134(1):194–200.

Bottesi G, Ghisi M, Ouimet AJ, Tira MD, Sanavio E. Compulsivity and impulsivity in pathological gambling: does a dimensional-transdiagnostic approach add clinical utility to DSM-5 classification? J Gambl Stud. 2015;31(3):825–47.

Kräplin A, Bühringer G, Oosterlaan J, Van den Brink W, Goschke T, Goudriaan AE. Dimensions and disorder specificity of impulsivity in pathological gambling. Addict Behav. 2014;39(11):1646–51.

Mallorquí-Bagué N, Fagundo AB, Jimenez-Murcia S, De La Torre R, Baños RM, Botella C, et al. Decision making impairment: a shared vulnerability in obesity, gambling disorder and substance use disorders? Weinstein AM, editor PLoS One 2016;11(9):e0163901.

Zhou Z, Zhou H, Zhu H. Working memory, executive function and impulsivity in internet-addictive disorders: a comparison with pathological gambling. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2016;28(2):92–100.

Vanes LD, van Holst RJ, Jansen JM, van den Brink W, Oosterlaan J, Goudriaan AE. Contingency learning in alcohol dependence and pathological gambling: learning and unlearning reward contingencies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1602–10.

Torres A, Catena A, Cándido A, Maldonado A, Megías A, Perales JC. Cocaine dependent individuals and gamblers present different associative learning anomalies in feedback-driven decision making: a behavioral and ERP study. Front Psychol. 2013;4(MAR):122.

• Majuri J, Joutsa J, Johansson J, Voon V, Alakurtti K, Parkkola R, et al. Dopamine and opioid neurotransmission in behavioral addictions: a comparative PET study in pathological gambling and binge eating. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;42(5):1169–77 One of the only studies to compare neurotransmitter functioning in gambling disorder and behavioral addictions.

Majuri J, Joutsa J, Johansson J, Voon V, Parkkola R, Alho H, et al. Serotonin transporter density in binge eating disorder and pathological gambling: a PET study with [11C]MADAM. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(12):1281–8.

Yip S, Morie K, Xu J, …, RC-B psychiatry, 2017 U. Shared microstructural features of behavioral and substance addictions revealed in areas of crossing fibers. Biol Psychiatry 2017;2(2):188–95.

Yip SW, Worhunsky PD, Xu J, Morie KP, Constable RT, Malison RT, et al. Gray-matter relationships to diagnostic and transdiagnostic features of drug and behavioral addictions. Addict Biol. 2018;23(1):394–402.

Kober H, Lacadie CM, Wexler BE, Malison RT, Sinha R, Potenza MN. Brain activity during cocaine craving and gambling urges: an fMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):628–37.

Ren Y, Fang J, Lv J, Hu X, Guo CC, Guo L, et al. Assessing the effects of cocaine dependence and pathological gambling using group-wise spare representation of natural stimulus fMRI data. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11(4):1179–91.

•• Zilberman N, Yadid G, Efrati Y, Neumark Y, Rassovsky Y. Personality profiles of substance and behavioral addictions. Addict Behav. 2018;82:174–81 This study was one of the more comprehensive case-control studies. It compared gambling disorder to both behavioral addictions and substance use disordere on personality and impulsivity.

Müller KW, Dreier M, Beutel ME, Wölfling K. Is sensation seeking a correlate of excessive behaviors and behavioral addictions? A detailed examination of patients with gambling disorder and internet addiction. Psychiatry Res. 2016;242:319–25.

Choi S-W, Kim H, Kim G-Y, Jeon Y, Park S, Lee J-Y, et al. Similarities and differences among internet gaming disorder, gambling disorder and alcohol use disorder: a focus on impulsivity and compulsivity. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(4):246–53.

Albein-Urios N, Martinez-González JM, Lozano Ó, Verdejo-Garcia A. Monetary delay discounting in gambling and cocaine dependence with personality comorbidities. Addict Behav. 2014;39(11):1658–62.

del Pino-Gutiérrez A, Jiménez-Murcia S, Fernández-Aranda F, Agüera Z, Granero R, Hakansson A, et al. The relevance of personality traits in impulsivity-related disorders: from substance use disorders and gambling disorder to bulimia nervosa. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):396–405.

Mallorquí-Bagué N, Fernández-Aranda F, Lozano-Madrid M, Granero R, Mestre-Bach G, Baño M, et al. Internet gaming disorder and online gambling disorder: clinical and personality correlates. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):669–77.

Farré JM, Fernández-Aranda F, Granero R, Aragay N, Mallorquí-Bague N, Ferrer V, et al. Sex addiction and gambling disorder: similarities and differences. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:59–68.

Granero R, Fernández-Aranda F, Mestre-Bach G, Steward T, Baño M, del Pino-Gutiérrez A, et al. Compulsive buying behavior: clinical comparison with other behavioral addictions. Front Psychol. 2016;7(JUN):914.

Jiménez-Murcia S, Granero R, Moragas L, Steiger H, Israel M, Aymamí N, et al. Differences and similarities between bulimia nervosa, compulsive buying and gambling disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(2):126–32.

Granero R, Fernández-Aranda F, Steward T, Mestre-Bach G, Baño M, del Pino-Gutiérrez A, et al. Compulsive buying behavior: characteristics of comorbidity with gambling disorder. Front Psychol. 2016;7(APR):625.

Tonioni F, Mazza M, Autullo G, Cappelluti R, Catalano V, Marano G, et al. Is Internet addiction a psychopathological condition distinct from pathological gambling? Addict Behav. 2014;39(6):1052–6.

Grbeša L, Martinac M, Romić M, Palameta N, Soldo V. Personality of alcoholics and gamblers in the Union of Clubs of Treated Alcoholics and Gamblers. Alcohol Psychiatry Res. 2016;52(2):125–32.

Müller KW, Beutel ME, Egloff B, Wölfling K. Investigating risk factors for internet gaming disorder: a comparison of patients with addictive gaming, pathological gamblers and healthy controls regarding the big five personality traits. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(3):129–36.

Gavriel-Fried B, Rabayov T. Similarities and differences between individuals seeking treatment for gambling problems vs. alcohol and substance use problems in relation to the progressive model of self-stigma. Front Psychol. 2017;8(JUN):957.

Schwaninger PV, Mueller SE, Dittmann R, Poespodihardjo R, Vogel M, Wiesbeck GA, et al. Patients with non-substance-related disorders report a similar profile of childhood trauma experiences compared to heroin-dependent patients. Am J Addict. 2017;26(3):215–20.

Manning V, Koh PK, Yang Y, Ng A, Guo S, Kandasami G, et al. Suicidal ideation and lifetime attempts in substance and gambling disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):706–9.

Derogatis L, Unger R. Symptom checklist-90 revised. Corsini Encycl Psychol 2010;1–2.

Hindmarch I, Kerr JS, Sherwood N. The effects of alcohol and other drugs on psychomotor performance and cognitive function. Alcohol Alcohol. 1991;26(1):71–9.

Shaffer HJ, LaPlante DA, LaBrie RA, Kidman RC, Donato AN, Stanton MV. Toward a syndrome model of addiction: multiple expressions, common etiology. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12(6):367–74.

Billieux J, Schimmenti A, Khazaal Y, Maurage P, Alexandre H. Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(3):119–23.

Kim HS, Hodgins DC. Component model of addiction treatment: a pragmatic transdiagnostic treatment model of behavioral and substance addictions. Front Psychiatry 2018;9(403).

Hodgins DC, Stea JN, Grant JE. Gambling disorders. Lancet. 2011;378(9806):1874–84.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Alana Guidry and Ximena Garcia for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.S., Hodgins, D.C. A Review of the Evidence for Considering Gambling Disorder (and Other Behavioral Addictions) as a Disorder Due to Addictive Behaviors in the ICD-11: a Focus on Case-Control Studies. Curr Addict Rep 6, 273–295 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00256-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00256-0