Abstract

Purpose of Review

This paper reviews the contribution of individual differences in two personality traits linked to addiction and over-consumption—impulsivity and reward sensitivity—in the context of overeating and food addiction.

Recent Findings

There has been a rapid increase in the number of studies into overeating with a specific focus of late on food addiction. This review found trait impulsivity to be consistently associated with overeating and food addiction, while reward sensitivity has met with mixed results. While associated with overeating and food-cued cravings, reward sensitivity is less frequently associated with food addiction.

Summary

The inclusion of impulsivity-related traits has gathered momentum in recent years adding additional understanding of individual factors that play roles in overeating that may lead to more severe overeating and obesity. Greater research is now required to determine the processes by which trait impulsivity and reward sensitivity lead to overeating behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The rapid increase in obesity rates across industrialised countries since the 1970s has been attributed in part to the unprecedented access to readily available, affordable, and highly palatable food [1]. This increase in obesity has been of concern in terms of the costs to the individual and to society [2]. In the Australian context, almost two-thirds of the population are overweight or obese: a 10% increase in the past 20 years [3]. Similar rates are found in the USA and other developed countries [4, 5]. While a wealth of research has investigated a range of contributing factors including changes in access to high calorie foods, in the nutritional content of food, portion size, and a general reduction in exercise [6], there is growing interest in the ‘addictive’ qualities of high caloric foods [6, 7] and the role that impulsivity traits play in the attraction towards, and lack of ability to inhibit, over-consumption of such food [8]. In this review, the focus is on the role of two related personality traits—impulsivity and reward sensitivity—in overeating, with a particular focus on food addiction.

Overeating and Food Addiction

Researchers have argued that overeating in today’s ‘obesogenic environment’ falls along a spectrum of eating behaviour that ranges from ‘passive overeating’ to binge eating, and at the most extreme level, to food addiction [6]. With a focus on overeating (rather than restrictive eating), this spectrum approach proposes a ‘downward escalating dimension’ that reflects an increase in severity and compulsiveness, from non-clinical occasional overeating (such as during festive occasions) through frequent overeating (snacking and grazing) to more serious binge episodes and clinically significant binge eating disorder (BED) and, at the extreme, food addiction [6].

Food addiction is characterised by the excessive overeating of high calorie food accompanied by loss of control and intense food cravings [9]. There has been a rapidly growing program of research supporting the links between food addiction and more traditional substance addictions [10, 11]. The impact of the concept is supported by a ninefold increase in the number of journal articles referring to food addiction from 2006 to 2010 [12]. More recent findings show an even greater increase in the publication of studies that explicitly use the term ‘food addiction’, with almost 90 papers in 2015 alone [13]. While many studies have included trait measures in the study of overeating and food addiction, few have taken an explicit personality perspective in exploring the role of such traits in the predisposition and maintenance of compulsive overeating [14•].

Facets of Impulsivity

Impulsivity is typically defined as ‘a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these reactions to the impulsive individual or to others’ [15]. While general ‘impulsivity’ plays a role in the development and maintenance of a range of excessive behaviours, including alcohol and drug abuse, problematic gambling, and overeating, there is consensus that this broad construct of impulsivity is multi-faceted [16]. In 2004, we proposed a two-factor model of impulsivity in relation to addiction with an emphasis on typical substances of abuse (e.g. alcohol and other drugs) and disordered eating [17, 18]. The first paper [17] reviewed factor analytic studies of impulsivity traits, while the second paper [18] reviewed the neuropsychological commonalities between impulsivity facets and addiction. The two facets in this model include (1) rash impulsivity and (2) reward sensitivity (also referred to as reward drive).

Rash Impulsivity

According to this model, rash impulsivity refers to an individual’s inability to stop an initiated approach response, i.e. a failure to ‘brake’ once a goal-directed approach response has started. Neurologically, this trait reflects individual differences in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex [18]. Research investigating this facet has found this specific trait to be associated with risky behaviours related to substance use (e.g. unsafe sexual practices, poly-substance use), and binge eating [8, 19, 20]. Rash impulsivity is frequently measured using self-report questionnaires such as the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale [21].

Reward Sensitivity

A component of Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory [22, 23], reward sensitivity, is a biologically based predisposition to seek out and respond positively to reward. Individuals high in this trait notice and seek out appetitive and rewarding substances and experiences. Reward sensitivity is proposed as the expression of an underlying Behavioural Approach System (BAS), which Corr [24] refers to as the ‘Let’s go for it!’ system. The mesolimbic dopamine ‘reward’ pathways in the midbrain have been proposed as the key biological basis of this trait [23]. The proposal that these neurological pathways underpin this motivational approach system (and by extension trait reward sensitivity) has been supported by numerous neuroimaging studies in which self-reported reward sensitivity has been related to increased activity in the ventral and dorsal striatum, ventral prefrontal cortex, and other midbrain regions [25]. Reward sensitivity is typically measured using self-report instruments such as the Carver and White Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS)/BAS scales [26] and Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire [27], although both scales were developed for an earlier iteration of the theory see [28•, 29•] for detailed reviews.

Rash Impulsivity and Reward Sensitivity

While there is an association between rash impulsivity and reward sensitivity—ranging from r = .16 [30] to r = .46 [31]—factor analyses support two distinct factors [17]. Furthermore, although both traits appear similar in behavioural outputs (i.e. approach behaviour), they differ in terms of the hypothesised underlying brain regions, and each is proposed to have independent mechanisms by which they contribute to the development of addictive behaviours [17, 18, 32, 33]. Given common neural pathways underlying reward sensitivity and neural response to substances of abuse and palatable foods, a core theme of recent research has been the proposal that highly reward-sensitive individuals are more susceptible to the rewarding properties of drugs of abuse and high fat/high sugary ‘tasty’ food [17, 34, 35]. Reward sensitivity has been found to be associated with the early experimentation with drugs [19] and alcohol [36], and greater learning of appetitive cue associations and expectancies of reward [37]. Rash impulsivity, on the other hand, appears to pose additional risk for dysfunctional approach behaviours and more severe problems with addictive behaviour [38]. Thus, while reward drive may set an approach response in action (e.g. food cravings and desire to eat in response to food images), the inability to brake (i.e. high rash impulsivity) may influence the outcome of the behaviour (recurrent binge episodes, loss of control, and an inability to cut down).

Rash Impulsivity, Reward Sensitivity, and Eating—Recent Findings

This theoretical model of impulsivity in addiction and, by extension, overeating (see [17] for the proposed application to eating behaviour) has been supported across a range of behavioural outcomes including binge eating [8, 32, 39••]. Schag and colleagues have provided two recent systematic reviews covering experimental studies investigating reward sensitivity and rash impulsivity in relation to binge eating and obesity [8, 39••]. They found individuals who are obese (with or without co-existing BED) to be higher in reward sensitivity relative to normal weight individuals without a co-existing BED, while those with BED were higher in rash impulsivity than obese individuals without BED. Given these recent, and comprehensive, reviews of experimental studies in the context of binge eating and obesity, this review will focus on recent studies that have used self-report measures of rash impulsivity and reward drive in the context of overeating and food addiction.

Rash Impulsivity and Overeating/Food Addiction

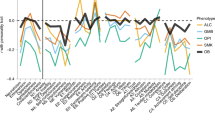

The relationship between high rash impulsivity and over-consumption of food is well established in individuals with both bulimia nervosa (BN), BED, and food addiction see [40] for an earlier review of impulsivity and disordered eating. Table 1 shows recent studies that have used established measures of rash impulsivity [17]. Given that this is a topic of recent interest, a particular focus is on food addiction as measured by the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) [9]. Of the studies reviewed in Table 1, the majority have used the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; this is a 30-item scale but referred to as the BIS-11 due to being the 11th version of the scale) [21] or the short 15-item version (BIS-15) [61]. Both the BIS-11 and the BIS-15 scale can be scored as a total score and/or three subscale scores: (1) attentional impulsivity (difficulties in maintaining attention or concentration), (2) motor impulsivity (acting without thinking), and (3) lack of planning (acting without forethought of future consequences). Other studies have used another measure of impulsivity—the UPPS-P, a five-factor scale based on the Big 5 theory of personality [62]—this measure has two subscales that assess the tendency to ‘act rashly’ in order to alleviate negative affect (negative Urgency), or enhance positive affect (Positive urgency)—these two subscales explicitly include an emotional aspect as well as impulsiveness. The remaining three subscales are as follows: (lack of) Perseverance/persistence (an inability to remain on task), (lack of) Planning/premeditation (a tendency to act without forethought of consequences), and Sensation seeking (the tendency to seek out novelty and, often risky, activities; see [32] for a discussion of differing models of impulsivity).

As shown in Table 1, across a range of samples including overweight/obese adults and adolescents, undergraduates, adults from the community, and those seeking treatment for weight-loss, high scores on the BIS-11 are consistently associated with meeting criteria for a food addiction diagnosis or with a greater number of food addiction symptoms [34, 41,42,43,44,45, 47, 48, 50, 53,54,55, 57, 58], although in some cases, the association is weak or more complex [51, 59]. This association appears to exist regardless of the use of the full or short measure of the BIS-11 or the use of the original or revised version of the YFAS. The BIS-11 was also associated with less eating restraint, greater hunger [43], greater externally driven eating (eating triggered by external cues such as the sight and smell of appetitive food), and greater emotional eating (the tendency to eat to alleviate negative moods) [47]. Surprisingly, disinhibited eating was not associated [47]. When examining studies that investigated the subscales of the BIS-11, attentional impulsivity appears to be most specifically associated with food addiction, although in a sample of mostly overweight/obese individuals with type II diabetes, all three subscales are strongly associated with YFAS symptom scores [53]. All three subscales were also associated with YFAS symptom scores in a sample of overweight/obese adolescents [50] and in a female general hospital outpatient sample [55]. In a sample of overweight/obese treatment-seeking patients, non-planning impulsivity was higher in those meeting criteria for food addiction [48], although this subscale has not been associated with food addiction in other studies [51]. In studies using the UPPS-P, the (negative) emotionally laden impulsivity scale was consistently associated with a food addiction diagnosis or greater number of symptoms [46, 52, 56, 60].

Across the studies, the association between the BIS/UPPS-P and food addiction is mostly between .20 and .30 in generally normal weight samples. One study investigating food addiction in overweight/obese participants with type II diabetes found associations as high as .80 for attentional impulsivity [53] and in another study of food addiction in treatment-seeking overweight/obese adolescents as high as .61, also for attentional impulsivity [50]. Meule [70] has recently advocated testing interactions between the three subscales with recent studies finding motor impulsivity to moderate the effect of attentional impulsivity and overeating and weight. University women high in both attentional impulsivity and motor impulsivity have been found to have greater body fat and report more overeating and binge eating symptoms and ate more sweet foods during a food taste test [49, 51]. In a bariatric surgery sample, those high in both attentional impulsivity and motor impulsivity were more likely to meet criteria for food addiction [59].

Overall, these studies support the role of an impulsive temperament in food addiction and other related overeating behaviours. The association appears stronger in those individuals seeking weight-reduction treatment or with additional health issues. The combination of attentional impulsivity and motor impulsivity may convey particularly high risk for overeating and food addiction [71]. While trait impulsivity as measured by the BIS-11 and UPPS-P is frequently assessed in studies of food addiction, reward sensitivity has tended to be only explicitly tested in more recent years.

Reward Sensitivity and Overeating/Food Addiction

Heightened reward sensitivity has been consistently associated with binge eating, meeting diagnosis for BN, and for having preferences for foods high in fat and sugar, and for colourful and varied food [72]. Compared with studies that incorporate the BIS-11 or the UPPS-P, far fewer studies have explicitly used purpose-built measures of reward sensitivity in food addiction studies (i.e. this review located only four published studies at this date [9, 34, 73, 74]). Table 2 presents recent studies that have used established, psychometrically sound self-reported reward sensitivity scales investigating food addiction and other forms of overeating, such as externally driven eating and emotional eating. As shown, and similar to rash impulsivity, there is consistency in the association between high reward sensitivity and external eating, emotional eating, fat intake, and a behavioural task assessing the willingness to work for food across samples of adults and children [34, 35, 37, 43, 47, 75,76,77,78,79, 81,82,83, 90].

However, the association between reward sensitivity and food addiction has met with mixed results with only one study thus far to have found a significant positive association [34]. Others that have included measures of reward sensitivity have not found any association [9, 73, 74]. This may be due to differences in the measures used to assess reward sensitivity. Studies that have used the total BAS scale score from the Carver and White BIS/BAS [26] scales have repeatedly failed to find a relationship between reward sensitivity and food addiction diagnosis or symptom score, whereas in the study that used the Torrubia et al. [27] Sensitivity to Reward (SR) scale has found this association [34]. The use of different measures of BAS has been problematic quite generally [28•, 29•, 91]. The widely used BIS/BAS scales consist of a single Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) scale (a measure of punishment sensitivity) and three BAS scales (fun-seeking, drive, reward responsiveness). However, many studies combine the three BAS subscales to form a total scale—this is problematic on a number of fronts. To start, confirmatory factor analyses consistently find a three-factor model to be a better fit than a single-factor model e.g. [92, 93]. More importantly, the BAS subscales also tend to correlate differentially with each other and with overeating [94, 95]. For example, Loxton and Dawe [94] found only the fun-seeking scale to be associated with dysfunctional eating in a sample of high school girls. Similar to Meule’s [70] proposal that BIS subscales should also be used to disentangle impulsivity components, using the total BAS score may have also missed finding significant associations that may be evident with specific subscales. However, none of the studies to date have reported subscale associations of the BAS scales and food addiction to determine if this is driving the apparent lack of association.

The general lack of association between self-reported reward sensitivity and food addiction is also contrary to other research that has found a multilocus genetic profile of heightened dopamine signalling (proposed as underlying the expression of reward sensitivity) to be associated with a score on an ‘addictive personality’ scale [96] and with food addiction [97]. Given the paucity of research that has used the SR scale or used the subscales of the BIS/BAS scales in food addiction, future research investigating reward sensitivity may be better served using measures that capture distinct BAS facets [98]. An alternate view is that the lack of association between self-reported reward sensitivity and food addiction specifically, relative to the consistent associations found with less severe overeating (external eating, emotional eating), is that while reward sensitivity increases the risk of overeating generally, rash impulsivity increases the escalation of occasional overeating to binge eating and food addiction in accord with Davis’s spectrum model of eating [6].

In sum, the association between reward sensitivity and more extreme levels of over-consumption is less consistent than with less severe forms of overeating such as externally driven eating. Nonetheless, there is clear support for this trait to be involved in overeating and potentially compulsive food consumption.

Future Directions

Potential Mechanisms Involved in the Expression of Traits and Overeating

The conditions by which trait impulsivity and reward sensitivity, in particular, foster overeating remain unclear. One area of recent attention and worthy of further investigation is on the role of reward sensitivity and food-cued cravings in over-consumption. A key factor in overeating is exposure to highly rewarding food cues that trigger intense food cravings [99••]. Those who meet criteria for food addiction and binge eating behaviours tend to show greater food-cued cravings relative to those who do not [41, 97, 100]. It is well established that the mesolimbic reward pathways (the putative neural substrates of reward sensitivity) are involved in memory formation of associations between eating and pleasure when consuming highly palatable foods. The smells and sights associated with tasty foods (e.g. the smell of pizza, pictures of chocolate) and stimuli that consistently predicts the consumption of palatable foods (e.g. time of day, being in a bad mood) all activate these reward pathways. Notably, these cues (even in the absence of the actual rewarding stimulus) activate the reward pathways even more strongly than the consumption of food itself [101, 102]. As such, those high in reward sensitivity are proposed as being more sensitive to both conditioned and conditioned rewards and, thus, will more readily learn these positive associations between food and food cues than less reward-sensitive individuals.

In two recent studies [35, 37], we found that reward-sensitive university women showed stronger associations (e.g. endorsed the belief that eating is a good way to celebrate) than less reward-sensitive women when presented with pictures of food on a computerised ‘expectancies’ task. This stronger association between the food pictures and positive beliefs about food was, in turn, associated with greater problematic eating. In two subsequent studies [90, 103], university women viewed a television program with either embedded ‘junk food’ advertisements or non-food advertisements. Reward sensitivity moderated the effect of the ‘junk food’ advertisements and change in urge to eat, with higher reward sensitivity associated with a greater increase in the urge to eat following the program, but only for those participants who viewed the ‘junk food’ advertisements. This increase in urge to eat in the high reward-sensitive participants in the ‘junk food’ condition was also associated with greater food consumption (chocolate consumption) following a ten-minute filler task [90]. Thus, the strong positive associations that high reward-sensitive individuals form with food cues, such as still and television images, may be one mechanism that drives overeating in these individuals and may be a point of intervention at both public policy (e.g. limiting ‘junk food’ advertising) and individual levels (e.g. targeting food-cued cravings in high reward-sensitive clients).

Effect of Consuming Junk Food on the Brain

Much of the work investigating reward sensitivity and overeating has been cross-sectional and typically used adult samples already displaying a high level of problematic behaviour (although there is a growing program of research investigating eating behaviour and reward sensitivity in children [76, 79,80,81, 83]). One of the complications when examining associations between personality traits and addictive behaviours is whether an innate predisposition to seek out reward and act impulsively leads to an increased risk of developing a subsequent problem, or whether consumption of high caloric foods alters neurological underpinnings involved in reward sensitivity/impulsiveness. There is some evidence from animal studies that long-term consumption of junk foods leads to alterations in these regions [104]. However, there has been little longitudinal research to test such effects in human beings. Stice and colleagues have started to make progress on this front by examining neural differences in the reward regions in normal weight children of obese parents [105] and advocate for future research to include similar designs to disentangle the reciprocal effects of excessive consumption of highly processed food and individual differences in impulsivity and reward sensitivity [106••]. Further research using such targeted samples and following up over time would help tease apart this complexity.

Conclusion

This review aimed to examine very recent studies using trait impulsivity and reward sensitivity in relation to overeating and food addiction. As shown, relative to studies of food addiction that have included well-established measures of impulsivity, there has a dearth of studies explicitly investigating the role of reward sensitivity. Largely, studies that have incorporated a measure of reward sensitivity have used a total score of an instrument in which there are three subscales that assess different components of this trait, thus possibly masking any differences in association. The studies using this approach find no association between reward sensitivity and food addiction. The one published study that did find an association used an alternative measure. This measure is not without criticism. A recent analysis of current measures of reward sensitivity found that a (short version) of the Sensitivity to Reward Scale captures trait impulsivity as well as reward sensitivity [91]. As such, the associations we have found between the SR scale and YFAS [34] may reflect both reward sensitivity and rash impulsivity. However, even when we controlled for rash impulsivity in this study, the model still held. It should also be noted that the measurement of reward sensitivity and the distinction between reward sensitivity (as proposed by Gray [23]) and impulsivity are currently a point of particular interest and debate in the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory field [28•, 29•]. A similar call to assess the three subscales (and potential interactions) of rash impulsivity measures has also been made [70, 71].

An alternate interpretation is that the relative consistency found between impulsivity and overeating across the overeating spectrum, including food addiction, and the inconsistency of reward sensitivity and food addiction may be that reward sensitivity plays a role in earlier stages of overeating, including responding to food cues, while rash impulsivity plays a greater role in the progression to more additive food consumption. This is in accord with the reviews by Schag and colleagues [8, 39••]. Stice and colleagues have also proposed that heightened sensitivity to reward may place individuals at risk of over-consumption, but with chronic, excessive overeating resulting in a blunted reward response, and associated reduction in inhibitory capacity [106••, 107]. To tease out these associations requires longitudinal studies using high-risk children and adolescents and well-designed experiments to make these distinctions.

While many studies in the area of overeating and food addiction allude to the importance of the reward and inhibitory pathways in the midbrain and prefrontal cortex in the attraction towards, and enjoyment of consuming highly palatable foods, only recently have biologically based personality factors, such as reward sensitivity, been a focus of attention. Granted that there still unresolved issues in the measurement of reward sensitivity, and to a lesser extent, impulsivity, attending to such individual differences may assist with more targeted prevention and intervention programs in overeating, and by extension, other addictive behaviours.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Colaguiri S, Lee CMY, Colaguiri R, Magliano D, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, et al. The cost of overweight and obesity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2010;192:260–4.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60460-8.

Australian Insiitute of Health and Welfare. A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia. Cat.no.PHE 216. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. p. 2017.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.39.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.40.

Davis C. From passive overeating to “food addiction”: a spectrum of compulsion and severity. ISRN Obesity. 2013;2013:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/435027.

Pursey KM, Davis C, Burrows TL. Nutritional aspects of food addiction. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(2):142–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0139-x.

Schag K, Schonleber J, Teufel M, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Food-related impulsivity in obesity and binge eating disorder—a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14(6):477–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12017.

Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009;52(2):430–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003.

Davis C. Evolutionary and neuropsychological perspectives on addictive behaviors and addictive substances: relevance to the “food addiction” construct. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2014;5:129–37. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S56835.

Meule A, Gearhardt AN. Five years of the Yale Food Addiction Scale: taking stock and moving forward. Curr Addict Rep. 2014;1:193–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-014-0021-z.

Gearhardt AN, Davis C, Kushner R, Brownell KD. The addiction potential of hyperpalatable foods. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:140–5.

Davis C. An introduction to the special issue on ‘food addiction’. Appetite. 2017;115:1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.043.

• Gullo MJ, Potenza MN. Impulsivity: mechanisms, moderators and implications for addictive behaviors. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1543–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.06.005. An editorial introduction to a special issue on the role of impulsivity in addiction with a focus on multidimensional facets of impulsivity, including reward sensitivity.

Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1783–93.

Meda SA, Stevens MC, Potenza MN, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Andrews MM, et al. Investigating the behavioral and self-report constructs of impulsivity domains using principal component analysis. Behav Pharm. 2009;20(5–6):390–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833113a3.

Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(3):343–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007.

Dawe S, Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ. Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: implications for substance misuse. Addict Behav. 2004;29(7):1389–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004.

Dissabandara LO, Loxton NJ, Dias SR, Dodd PR, Daglish M, Stadlin A. Dependent heroin use and associated risky behaviour: the role of rash impulsiveness and reward sensitivity. Addict Behav. 2014;39(1):71–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.009.

Schag K, Teufel M, Junne F, Preissl H, Hautzinger M, Zipfel S, et al. Impulsivity in binge eating disorder: food cues elicit increased reward responses and disinhibition. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076542.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psych. 1995;51:768–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679.

Gray JA. The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extraversion. Behav Res Ther. 1970;8:249–66.

Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: an enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. 2nd ed. Oxford psychology series 33. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Corr PJ. The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality. In: Corr PJ, Matthews G, editors. Cambridge handbook of personality psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 347–76.

Kennis M, Rademaker AR, Geuze E. Neural correlates of personality: an integrative review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(1):73–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.012.

Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67(2):319–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.31.

Torrubia R, Avila C, Molto J, Caseras X. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31(6):837–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00183-5.

• Corr PJ. Reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality questionnaires: structural survey with recommendations. Pers Individ Dif. 2016;89:60–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.045. Reviews the current state of self-report measures used in light of the major revision of the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of personality

• Walker BR, Jackson CJ. Examining the validity of the revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory scales. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;106:90–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.035. Systematically reviews self-report measures purposely built to measure the Revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory and provides guidance on choosing measures of this theory.

Gullo MJ, Dawe S, Kambouropoulos N, Staiger PK, Jackson CJ. Alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy mediate the association of impulsivity with alcohol misuse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010:1386–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01222.x.

Harnett PH, Lynch SJ, Gullo MJ, Dawe S, Loxton N. Personality, cognition and hazardous drinking: support for the 2-component approach to reinforcing substances model. Addict Behav. 2013;38(12):2945–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.017.

Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ, Dawe S. Impulsivity: four ways five factors are not basic to addiction. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1547–56.

Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ, Price T, Voisey J, Young RM, Connor JP. A laboratory model of impulsivity and alcohol use in late adolescence. Behav Res Ther. 2017;97:52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.003.

Loxton NJ, Tipman RJ. Reward sensitivity and food addiction in women. Appetite. 2017;115:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.10.022.

Maxwell AL, Loxton NJ, Hennegan JM. Exposure to food cues moderates the indirect effect of reward sensitivity and external eating via implicit eating expectancies. Appetite. 2017;111:135–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.037.

Lyvers M, Duff H, Basch V, Edwards MS. Rash impulsiveness and reward sensitivity in relation to risky drinking by university students: potential roles of frontal systems. Addict Behav. 2012;37(8):940–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.028.

Hennegan JM, Loxton NJ, Mattar A. Great expectations. Eating expectancies as mediators of reinforcement sensitivity and eating. Appetite. 2013;71:81–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.07.013.

Loxton NJ, Wan VL, Ho AM, Cheung BK, Tam N, Leung FY, et al. Impulsivity in Hong Kong-Chinese club-drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(1–2):81–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.009.

•• Giel KE, Teufel M, Junne F, Zipfel S, Schag K. Food-related impulsivity in obesity and binge eating disorder—a systematic update of the evidence. Nutrients. 2017;9(11) https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111170. Provides a systematic review of 20 studies since 2012 looking at obesity/binge eating disorder and impulsivity/reward sensitivity including studies using food cue exposure and across adults and children. Focus in this review is primarily on behavioral tasks assessing impulsivity and reward sensitivity.

Waxman SE. A systematic review of impulsivity in eating disorders. European eating disorders review : the journal of the Eating Disorders Association. 2009;17(6):408–425.

Davis C, Curtis C, Levitan RD, Carter JC, Kaplan AS, Kennedy JL. Evidence that ‘food addiction’ is a valid phenotype of obesity. Appetite. 2011;57(3):711–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.017.

Meule A, Lutz A, Vogele C, Kubler A. Women with elevated food addiction symptoms show accelerated reactions, but no impaired inhibitory control, in response to pictures of high-calorie food-cues. Eat Behav. 2012;13(4):423–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.08.001.

Dietrich A, Federbusch M, Grellmann C, Villringer A, Horstmann A. Body weight status, eating behavior, sensitivity to reward/punishment, and gender: relationships and interdependencies. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1073. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01073.

Meule A, Lutz APC, Vögele C, Kübler A. Impulsive reactions to food-cues predict subsequent food craving. Eat Behav. 2014;15:99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.023.

Meule A, Heckel D, Jurowich CF, Vogele C, Kubler A. Correlates of food addiction in obese individuals seeking bariatric surgery. Clin Obes. 2014;4(4):228–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12065.

Murphy CM, Stojek MK, MacKillop J. Interrelationships among impulsive personality traits, food addiction, and body mass index. Appetite. 2014;73:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.008.

Stapleton P, Whitehead M. Dysfunctional eating in an Australian community sample: the role of emotion regulation, impulsivity, and reward and punishment sensitivity. Aust Psychol. 2014;49(6):358–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12070.

Ceccarini M, Manzoni GM, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E. An evaluation of the Italian version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale in obese adult inpatients engaged in a 1-month-weight-loss treatment. J Med Food. 2015;18(11):1281–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2014.0188.

Kakoschke N, Kemps E, Tiggemann M. External eating mediates the relationship between impulsivity and unhealthy food intake. Physiol Behav. 2015;147:117–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.04.030.

Meule A, Hermann T, Kubler A. Food addiction in overweight and obese adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev: J Eat Disord Assoc. 2015;23(3):193–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2355.

Meule A, Platte P. Facets of impulsivity interactively predict body fat and binge eating in young women. Appetite. 2015;87:352–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.01.003.

Pivarunas B, Conner BT. Impulsivity and emotion dysregulation as predictors of food addiction. Eat Behav. 2015;19:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.06.007.

Raymond KL, Lovell GP. Food addiction symptomology, impulsivity, mood, and body mass index in people with type two diabetes. Appetite. 2015;95:383–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.030.

Ivezaj V, White MA, Grilo CM. Examining binge-eating disorder and food addiction in adults with overweight and obesity. Obesity. 2016;24(10):2064–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21607.

Omar AEM, ElRasheed AH, Azzam HMEE, ElZoheiry AK, ElSerafi DM, ElGhamry RH, et al. Personality profile and affect regulation in relation to food addiction among a sample of Egyptian females. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2016;15(3):143–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/adt.0000000000000084.

Wolz I, Hilker I, Granero R, Jimenez-Murcia S, Gearhardt AN, Dieguez C, et al. “Food addiction” in patients with eating disorders is associated with negative urgency and difficulties to focus on long-term goals. Front Psychol. 2016;7:61. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00061.

de Vries SK, Meule A. Food addiction and bulimia nervosa: new data based on the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0. Eur Eat Disord Rev: J Eat Disord Assoc. 2016;24(6):518–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2470.

Meule A, Muller A, Gearhardt AN, Blechert J. German version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0: prevalence and correlates of ‘food addiction’ in students and obese individuals. Appetite. 2017;115:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.10.003.

Meule A, de Zwaan M, Muller A. Attentional and motor impulsivity interactively predict ‘food addiction’ in obese individuals. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;72:83–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.10.001.

VanderBroek-Stice L, Stojek MK, Beach SR, vanDellen MR, MacKillop J. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in relation to obesity and food addiction. Appetite. 2017;112:59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.009.

Spinella M. Normative data and a short form of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Int J Neurosci. 2007;117(3):359–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450600588881.

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30(4):669–89.

Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behaviour: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:107–18.

Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Development of the Yale Food Addiction Scale version 2.0. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(1):113–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000136.

Innamorati M, Imperatori C, Manzoni GM, Lamis DA, Castelnuovo G, Tamburello A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Italian Yale Food Addiction Scale in overweight and obese patients. Eat Weight Disord. 2015;20(1):119–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0142-3.

Van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB. The Dutch eating behaviour questionnaire for assessment of restrained, emotional and external eating behaviour. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5:295–315.

Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating inventory to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83.

Lowe MR, Butryn ML, Didie ER, Annunziato RA, Thomas JG, Crerand CE, et al. The Power of Food Scale. A new measure of the psychological influence of the food environment. Appetite. 2009;53(1):114–8.

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(4):363–70.

Meule A. Impulsivity and overeating: a closer look at the subscales of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Front Psychol. 2013;4:177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00177.

Meule A. Commentary: questionnaire and behavioral task measures of impulsivity are differentially associated with body mass index: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01222.

Loxton NJ, Dawe S. Personality and eating disorders. In: Corr PJ, Matthews G, editors. Cambridge handbook of personality psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 687–703.

Clark SM, Saules KK. Validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale among a weight-loss surgery population. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):216–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.002.

Chen G, Tang Z, Guo G, Liu X, Xiao S. The Chinese version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale: an examination of its validation in a sample of female adolescents. Eat Behav. 2015;18:97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.05.002.

Matton A, Goossens L, Braet C, Vervaet M. Punishment and reward sensitivity: are naturally occurring clusters in these traits related to eating and weight problems in adolescents? Eur Eat Disord Rev:J Eat Disord Assoc. 2013;21(3):184–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2226.

Rollins BY, Loken E, Savage JS, Birch LL. Measurement of food reinforcement in preschool children. Associations with food intake, BMI, and reward sensitivity. Appetite. 2013;72C:21–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.018.

Tapper K, Baker L, Jiga-Boy G, Haddock G, Maio GR. Sensitivity to reward and punishment: associations with diet, alcohol consumption, and smoking. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;72:79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.025.

Li X, Tao Q, Fang Y, Cheng C, Hao Y, Qi J, et al. Reward sensitivity predicts ice cream-related attentional bias assessed by inattentional blindness. Appetite. 2015;89:258–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.010.

De Decker A, Sioen I, Verbeken S, Braet C, Michels N, De Henauw S. Associations of reward sensitivity with food consumption, activity pattern, and BMI in children. Appetite. 2016;100:189–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.028.

Vandeweghe L, Vervoort L, Verbeken S, Moens E, Braet C. Food approach and food avoidance in young children: relation with reward sensitivity and punishment sensitivity. Front Psychol. 2016;07 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00928.

De Decker A, De Clercq B, Verbeken S, Wells JCK, Braet C, Michels N, et al. Fat and lean tissue accretion in relation to reward motivation in children. Appetite. 2017;108:317–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.10.017.

Matton A, Goossens L, Vervaet M, Braet C. Effortful control as a moderator in the association between punishment and reward sensitivity and eating styles in adolescent boys and girls. Appetite. 2017;111:177–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.002.

Vandeweghe L, Verbeken S, Vervoort L, Moens E, Braet C. Reward sensitivity and body weight: the intervening role of food responsive behavior and external eating. Appetite. 2017;112:150–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.014.

Jackson C. The Jackson-5 Scales of revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST) and their application to functional and dysfunctional real world outcomes. J Res Pers. 2009;43:556–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.02.007.

Margetts B, Cade J, Osmond C. Comparison of a food frequnecy questionnaire with a diet record. Int J Epidem. 1989;18:868–73.

Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, Thijs C. The Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: factorial validity and association with body mass index in Dutch children aged 6-7. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:49.

Epstein LH, Wright SM, Paluch RA, Leddy J, Hawk LW Jr, Jaroni JL, et al. Food hedonics and reinforcement as determinants of laboratory food intake in smokers. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(3):511–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.015.

Blair C. Behavioral inhibition and behavioral activation in young children: relations with self-regulation and adaptation to preschool in children attending Head Start. Dev Psychobiol. 2003;42(3):301–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.10103.

Colder CR, O'Connor RM. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity model and child psychpathology: laboratory and questionnaire assessment of the BAS and BIS. J Abnorm Child Psych. 2004;32:435–51.

Kidd C, Loxton NJ. Junk food advertising moderates the indirect effect of reward sensitivity and food consumption via the urge to eat. Physiol Behav. 2018;188:276–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.02.030.

Krupić D, Corr PJ, Ručević S, Križanić V, Gračanin A. Five reinforcement sensitivity theory (RST) of personality questionnaires: comparison, validity and generalization. Pers Individ Dif. 2016;97:19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.012.

Heubeck BG, Wilkinson RB, Cologon J. A second look at Carver and White’s (1994) BIS/BAS scales. Pers Individ Dif. 1998;25(4):785–800.

Jorm AF, Christensen H, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA, Korten AE, Rodgers B. Using the BIS/BAS scales to measure behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation: factor structure, validity and norms in a large community sample. Pers Individ Dif. 1999;26(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00143-3.

Loxton NJ, Dawe S. Alcohol abuse and dysfunctional eating in adolescent girls: the influence of individual differences in sensitivity to reward and punishment. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29(4):455–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1042.

Voigt DC, Dillard JP, Braddock KH, Anderson JW, Sopory P, Stephenson MT. BIS/BAS scales and their relationship to risky health behaviours. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47:89–93.

Davis C, Loxton NJ. Addictive behaviours and addiction-prone personality traits: associations with a dopamine multilocus genetic profile. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2306–12.

Davis C, Loxton NJ, Levitan RD, Kaplan AS, Carter JC, Kennedy JL. Food addiction’ and its association with a dopaminergic multilocus genetic profile. Physiol Behav. 2013;118:63–9.

Corr PJ, Cooper AJ. The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality Questionnaire (RST-PQ): development and validation. Psychol Assess. 2016;28:1427–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000273.

•• Schulte EM, Joyner MA, Schiestl ET, Gearhardt AN. Future directions in “food addiction”: next steps and treatment implications. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(2):165–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0140-4. Reviews the current state of research in food addiction and the implications for treatment and provides future directions including greater examination of food exposure and cued cravings in addtion to presenting the current literature related to negative affect.

Meule A, Kübler A. Food cravings in food addiction: the distinct role of positive reinforcement. Eat Behav. 2012;13(3):252–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.02.001.

Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Gerber RA, Leidy NK, Sexton CC, Karlsson J, et al. Evaluating the Power of Food Scale in obese subjects and a general sample of individuals: development and measurement properties. Int J Obes. 2009;33(8):913–22.

Schultz W. Predictive reward signals of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27.

Loxton NJ, Byrnes S. Reward sensitivity increases food “wanting” following television “junk food” commercials [abstract]. Appetite. 2012;59, Supp 1(Supp 1):e38.

Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:635–41.

Stice E, Yokum S, Burger KS, Epstein LH, Small DM. Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4360–6. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6604-10.2011.

•• Stice E, Shaw H. Eating disorders: insights from imaging and behavioral approaches to treatment. J Psychopharm. 2017;31:1485–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988111772. Reviews prospective studies of factors that predict the onset and maintenance of eating disorders with implications for prevention and treatment programs. Reviews research using reward sensitivity and lack of inhibitory control.

Burger KS, Stice E. Variability in reward responsivity and obesity: evidence from brain imaging studies. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:182–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Food Addiction

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Loxton, N.J. The Role of Reward Sensitivity and Impulsivity in Overeating and Food Addiction. Curr Addict Rep 5, 212–222 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0206-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0206-y