Abstract

This article reports an investigative study of business communication needs of English major undergraduates and their perceptions of effective business English curriculum in a Chinese university. Surveys in two stages were administered in 2015 during the Business English Communication course delivery process to 138 English major undergraduates in a public university located in the east of China. The results include stronger English speaking needs, diverse English writing genres, wide native and non-native English speaker contacts, and difficulties in comprehending original English communication. The participants valued business knowledge introductions, company cases, and authentic material input. They also perceived practice-oriented approaches such as presentations and role play as important parts of effective business English curriculum. The results help to further adapt the business English curriculum based on the recent national benchmark and bring better business communicative competence development outcomes, which have theoretical, practical, and policy implications for both China and the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While Feng (2012) highlighted the growing trend of English use in the social and cultural contexts in Greater China region, including mainland China’s educational institutions, the effectiveness of English language teaching in the Chinese context is still an issue under discussion. For example, Yang (2006) indicated that the effectiveness of China’s college English language teaching was constrained by shortage of English use context, lack of sufficient comprehensible input, and instructional time in class. Even the college English graduates in China may not have adequate English communicative competence to cope with the challenges of the globalized workplace. Nevertheless, the overall aim of China’s college and university English teaching and assessment has been to develop communicative competence to meet the social needs, also stated in the College English Test development committee report (Jin and Yang 2006).

This article is to address the issues of English language teaching in China’s university context by investigating the business English communication needs of English major undergraduates to see whether this thorough understanding can feed into the actual curriculum development to ultimately bring better communicative competence development outcomes.

Theoretical Framework

Understanding English Teaching and Learning in China’s Universities

Previous studies have discussed English teaching and learning in China’s university context. Wette and Barkhuizen (2009) reported that under the pressure of passing College English Test and developing communicative competence, teachers were facing increasing challenges of satisfying student needs, course requirements, and using their own unique teaching theories for excellent practices. Teachers had to not only follow the syllabus and teaching plan, but also pay attention to students’ personal development. Stanley (2011) further summarized that English language teaching in China’s university context tended to be constrained by assessment pressure, teachers’ inadequate English language competence, and the class size problems. The real communicative competence development process was sometimes marginalized.

From the learners’ perspective, in the study by Gao et al. (2005) on English learning among Chinese undergraduates, English major students were demonstrating more changes in their identity by enhancing self-confidence and their language use competence through English learning. Based on a more recent sociolinguistic study in two Chinese universities in Macau and Guangzhou, Botha (2014) reported that due to the increase of English Medium Instruction in China’s universities, students’ academic approach to English language learning has also been changed. In addition, Chinese students have also been exposed to more English varieties in their daily lives, such as internet, movies, and video games. These have increasingly transformed the types of English communication in and out of class within the current higher education environment.

To explore the changing education landscapes which influence the university students’ English learning process and to identify the pathway to bridge the gap between student needs and curriculum development for better communicative competence development outcomes, continuous needs analysis processes are required.

Review of Needs Analysis Processes

Needs analysis process was first widely adopted in the English for specific purposes (ESP) programs (Hutchinson and Waters 1987), to gather information such as “necessities, lacks and wants” (p. 55) in the English learning process. The information gathering tools have included “questionnaire, interviews, observation, text collection and informal consultation” (p. 58). Moreover, Long (2005, p. 31) also included other data collection instruments such as “ethnographic methods, diaries, role plays and triangulated methods”. Multiple sources of information and methods can be used in the needs analysis process to enable triangulation (Cowling 2007).

Needs analysis approach has also been applied in general English language teaching. The scope of analysis mainly covers not only target situation analysis but also present situation analysis such as “deficiency analysis, strategy analysis, language audits (mainly for the companies), computer-assisted analyses, and material selection” (West 1994, p. 1). Needs analysis is as critical as course evaluation, both of which follow similar methodologies (Dudley-Evans and St John 1998, p. 122), are ongoing and inform curriculum development.

Analyzing Business Communication Needs in the Academic Context and Curriculum Development

Previous studies conducted both present situation analysis and target situation analysis to understand the business communication needs of industry practitioners and the learners in the educational institutions. In Malaysia, Moslehifara and Ibrahim (2012) investigated the English language communication needs required by human resources development (HRD) trainees at the workplace using a set questionnaire. The findings included trainees’ recognition of the importance of oral English communication skills, the most critical oral communication skills such as social interaction, training activities as well as the difficulties encountered in oral communication in the workplace. It was indicated that skills such as “conversation, oral presentation and discussion” (p. 536) should be covered in the English enhancement programs. In Romania, Şimon (2014) reported on the study of oral English communication skills development for the professional context in the bachelor program Communication and Public Relations. The students’ unwillingness to communicate may constrain the oral skills development process which could be caused by external factors such as classroom arrangement and internal factors such as lack of motivation and autonomy to practice oral English skills.

In mainland China, Zhang (2014) conducted target situation needs analysis by surveying 20 business representatives as well as present situation analysis by investigating 30 undergraduates using questionnaires generated by Dudley-Evans and St John’s conceptual framework. The study showed that businesses needed graduates to have business communication skills, international business knowledge, and cross-cultural awareness. While students were aware of the importance of business English skills, the course implementation posed challenges for English teachers as practical experience, business knowledge, and acumen were required to optimize the balance between in-class instruction and out-of-class resource provision.

Zhang and Wang (2012) in another research studied the undergraduate English major students’ motivation of learning English for business and economics, which can be categorized into the factors of employment, program study, personal development, social responsibility, external influence, internal interest, and interest in English learning. In another context, Zheng (2011) also studied the business English needs of English majors in Zhejiang University, China. By investigating the communication skill needs, teaching method preferences, curriculum, material, and assessment evaluation using a questionnaire, a gap was identified between the business English needs and curriculum. Ongoing needs analysis may be needed to assess the student learning progress and improve the curriculum.

Research Questions

Based on the constructed theoretical framework, this study aims to further investigate the business communication needs of English major undergraduates and their perceptions of business English curriculum in a Chinese university context. Approaches for more effective business communicative competence development can be identified from the learners’ perspective. This study addresses the following two research questions:

-

1)

What are the business communication needs of English major undergraduates in the Chinese university context?

-

2)

What are the English major undergraduates’ perceptions of effective business English curriculum?

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design and process. As this study aims to investigate the business English needs of English major undergraduates and their perceptions of curriculum development, both numerical and non-numerical information is to be collected. The methodology is both quantitative and qualitative by nature (Brown 2014). The data collection instruments are two-stage surveys, including both quantitative rating and qualitative open-ended questions for gathering comprehensive information from the learners. This study chooses one public university in the east of China, which houses a four-year undergraduate program of English language and literature. The program contains business English related courses. The data collection process, participants, and data analysis procedures are described in the following sections.

Data Collection

Stage One: Business English Communication Needs Survey

The business communication needs questionnaire (see Appendix 1) was administered in the first week of Business English Communication course in September 2015. The survey consists of questions related to the communication skills needing improvement, the business document participants often write, the situations participants often listen, the types, and nationalities of people participants often speak with and the difficulties in the communication process. The survey questions were based on the interview sheet designed by Freeman (2009, p.1), and Ellis and Johnson (2002, p. 84).

Stage Two: Business English Curriculum Needs Assessment

The business communication curriculum assessment sheet (see Appendix 2) was administered in the last week of the Business English Communication course in December 2015, to solicit student needs on the curriculum, including teaching approaches, materials, activities, and helpfulness of the course to enhance business communicative competence. There are rating and open-ended questions related to written and spoken materials and activities to be included in the course, the most useful part of the course, other elements which can be included, and students’ perceptions of an effective business English course, adapted from the questionnaires designed by Chaudron et al. (2005, p. 258) and Chan (2014, p. 401).

Participants

The participant profiles for the surveys are provided in Table 1. 138 second year undergraduates in the program of English language and literature program who enrolled in the Business English Communication course participated in the surveys. 88 % of them are female, and 12 % are male students. Their average age is 19.6 years old. Their age range is between 18 and 21 years old. 14 % of them passed College English Test Band 4 (CET-4). Very few participants reported passing higher level English proficiency test, such as CET-6 and Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL).

Data Analysis

In most parts of survey result analysis, frequency calculations have been conducted to identify the most common business communication needs of the participants, while mean has also been calculated related to their preferences of key content in the business English curriculum, which are typical approaches in needs analysis research (Brown 2014, p. 7). In analyzing the second part of the survey on curriculum assessment, the researcher has identified the themes (Guest et al. 2012) from participants’ response to open-ended questions and also provided some typical quotes to demonstrate the unique curriculum needs of English major undergraduates in this Chinese university.

Findings

The Business Communication Needs of English Major Undergraduates in the Chinese University Context

English skill areas which students require improvement are listed in Table 2. The results have shown that these English major undergraduates need to improve English speaking skill the most, as 35 % of the participants placed it as the priority area for language enhancement, followed by 16 % in English writing and listening, respectively. Vocabulary enhancement takes up 11 % of the participants. Less than 5 % of the participants particularly required improvement in English reading and grammar.

Documents students most often write in English are explained in Table 3. 28 % of the participants most often write English general interest articles, followed by 20 % on reports, and 12 % on informal/chatty E-mails. Less than 10 % of the participants often write chat pages and memos in English.

Situations students often listen in English are presented in Table 4. 46 % of the participants often have to listen to conferences in English. 30 % of the participants have to listen to one-on-one phone calls in English, while 21 % of them listen to meetings of 3 or more people in English. Listening to English socializing takes up 20 % of the participants. More than 10 % of the participants listen to presentations and conference calls in English. Less than 10 % of the participants listen to one-on-one meetings in English.

The composition of the nationalities of people students often speak with is presented in Table 5. More than 30 % of the participants often speak with native speakers from USA. They could be their foreign teachers and friends. 25 % of them speak to non-native English speakers from China, who come from different regions, such as Anhui Province, Jiangsu Province in the east, and Hei Longjiang Province in the northeast. These non-native English speakers from China may include their Chinese English teachers and friends. Less than 20 % of the participants speak in mixed native/non-native groups. Less than 10 % of the participants often speak with people from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and UK, who are native speakers. A few participants indicated the chance to speak with non-native speakers from other parts of the world, including European countries, such as France, Italy, Spain, Poland, Romania, Portugal, Southeast Asia, Arabian countries, and East Asian countries such as Japan and Korea.

The diversity of the students’ exposure to speakers from various countries could be due to their study circle which enabled them to get in touch with overseas teachers and foreign students. A few participants had more opportunities because of their active participation in student organized extra-curricular activities such as those by the Association for Overseas Students.

In response to the questions on the difficulties in the business communication process, participants indicated that the accents of the speakers from India, Korea or New Zealand created problems in their communication. The speed of the speech sometimes also created difficulties in understanding. A few participants indicated their own limitations in vocabulary, and grammar, which enlarged the gap of communication with both native and non-native speakers. There could be some slangs or special jargons in the business context which the participants were not able to catch in the communication process.

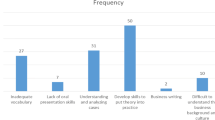

English Major Undergraduates’ Perceptions of Effective Business English Curriculum

For the preferences of course content and activities in both written and spoken forms, participants have rated their most needed and least needed parts in a range of 1 to 5, where 1 represents the least needed while 5 the most needed. The results are summarized in Table 6 (written) and Table 7 (spoken), respectively.

In the written input, business knowledge introductions, business English word list, writing templates, and Business English Certificate (BEC) test preparation materials have the highest mean, all over 4. The results may be due to the fact that participants belong to the pre-experience group and have little exposure to the real business world, though they need BEC to get ready for the job market. They rely on teachers to provide them with business context introductions, which is confirmed in the following comment by participant A:

Since we are the amateur of the business English, we don’t know much about business and companies or we didn’t pay much attention in our daily life so we need the teacher to introduce us more about that.

More specifically, participants emphasized that the authentic writing templates collected from the workplaces were important for learning different business communication activities. For example, participant B had the following comment:

I think the most important part to me is how to write a standard e-mail or fax, including the content of it. What kind of content is suitable for different kinds of e-mails or faxes? Business knowledge introduction is also very important, because some time we’ll feel puzzled without some business knowledge.

Most of the participants preferred to have business cases to enrich their understanding of the field. Participant C had the following typical comment:

The teaching materials can include some famous cases like large foreign corporations. How the leaders of these corporations operate their company? What are the employee benefits or work environment.

For the business context, participants also had very specific ideas such as these raised by participant D:

The introduction of how a company promote its products, how to advertise, how to build materials, how to earn customers.

In the spoken part, spoken practices via presentations, role-plays, group activities etc. receive the highest mean, while spoken templates also have mean over 4.

Participants have praised the presentations and indicated that role play can simulate the communication in the real workplace. Participant E had the following explanations in the response:

Maybe we can simulate the scene of business communication in class, make the role-play effective, which needs preparation. I think the presentation is effective to enrich our own knowledge.

When describing the perceptions of an effective business English course, participants have shown different perspectives. One part of the views focused on the needs of understanding authentic business communication in the workplaces. The following two descriptions are quite typical:

In my opinion, at an effective business English course, teachers will teach us the different social manners and ways to greet people and that we should do and say when socializing. Also, teachers will give us knowledge on all kinds of business English terms. Teacher will give students chances to try to socialize and then give their suggestions. (Participant F).

I think it should let us know more about real business like what will really happen in today’s business world and the authentic way of communication. (Participant G).

Another part of the views focused on business communicative competence development through practice-based approach. The following two statements addressed the practice-oriented approach from learners’ point of view.

An effective business English course is very lively, I think. Each class, students have the chance to practice conversations and imitate some formal business conversations and communications. After class, students need to do a full range of research on some famous companies, which is beneficial to improving our skills. (Participant H).

Half teaching–learning, half practice-learning. More speaking than writing in class. (Participant I).

Discussion and Conclusions

In describing the business communication needs of English major undergraduate students in the Chinese university context, different from workplace professionals reported in the study of Chan (2014), participants have expressed stronger willingness to develop oral communication skills. They have their specific writing and listening needs, influenced by their university life. Some of the participants also have a wide contact with native and non-native English speakers from different areas of the world. They may sometimes have comprehension problems in the communication process. In a similar context, Wolff (2009, p. 256) summarized that due to the fact that English is increasingly becoming a “global lingua franca”, students need to be exposed in the curriculum a variety of accents, both formal and informal English, and a great range of texts with different genres and registers in English etc., so that they will have the flexibility to cope with the changes in global communication and gradually cultivate the intercultural adaptation. Thereby, the business English curriculum for this study should be adapted based on this understanding of student needs to increase the oral communication content, English as a global lingua franca orientation, and intercultural communication practice. Moreover, based on the student needs in the second part of the survey, the business English curriculum should also increase more of the authentic business communication templates, business lexicography, and some additional materials for business knowledge introductions, company cases, and even BEC test preparation.

From the course implementation theory perspective, Leaver and Shekhtman (2002, p.5) have indicated different elements in the English language classes such as “goal, theory, class work, home assignments, role of teacher, grouping, tests and syllabus”. They are based on three types of educational philosophies, i.e., “transmission, transaction and transformation”. These mean to transmit knowledge, develop skills, and cultivate abilities. In the business English curriculum for this study, these educational typologies are all important, in order to have better communicative competence development outcomes. The focus of the curriculum change should be to increase practice-oriented approaches through project or task and students’ autonomous learning. The change should also be directed towards enriching the authentic material and business knowledge input, in which teacher plays more important roles. For further upgrading of the business English curriculum, Wang and Li (2011) have also proposed two useful routes, i.e., the incorporation of technology-assisted learning to enhance the effectiveness of business English practice in the curriculum and the adoption of content-based instruction (CBI) in teaching business knowledge which students claim shortage in this study.

Broadly, for business English curriculum in China’s university context, it is specified in the national benchmark document that the aim is to train students with knowledge of language, business, culture, humanity and interdisciplinary areas and to develop the competencies of language use, cross-cultural communication, business practice, critical thinking and innovation, and autonomous learning (Wang et al. 2015). It is thereby justified that business English courses in China’s university context should not only focus on the business English language use but also other related knowledge areas and the cultivation of competencies which enable students to be successful in the workplace. This benchmark guides further development of business English curriculum, based on thorough understanding of learner needs.

To sum up, this study serves as an example to inform research and practice, which shows how understanding students’ business communication needs and perceptions can help improve the business English curriculum. While meeting learner needs, better business communicative competence development outcome can be achieved. Meanwhile, the curriculum adaptation in teaching and learning approach also bears educational significance. Methodologically, although this study reports survey findings in only one public university in China, the research process can be replicated in other regional or cultural contexts. Future business English curriculum development in the higher education context can be predicted in this way.

References

Botha, W. (2014). English in China’s universities today. English Today, 30, 3–10. doi:10.1017/S0266078413000497.

Brown, J. D. (2014). Mixed methods research for TESOL. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Chan, M. (2014). Communicative needs in the workplace and curriculum development of business English courses in Hong Kong. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 77(4), 376–408. doi:10.1177/2329490614545987.

Chaudron, C., Doughty, D. J., Kim, Y. K., Kong, D. K., Lee, J. H., Lee, Y. G., et al. (2005). Chapter 8 A task-based needs analysis of a tertiary Korean as a foreign language program. In M. Long (Ed.), Second Language Needs by Analysis (pp. 225–261). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cowling, J. D. (2007). Needs analysis: planning a syllabus for a series of intensive workplace courses at a leading Japanese company. English for Specific Purposes, 26, 426–442. doi:10.1016/j.esp.2006.10.003.

Dudley-Evans, T., & St John, M. J. (1998). Developments in ESP: a multidisciplinary approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, M., & Johnson, C. (2002). Teaching business English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feng, A. W. (2012). Spread of English across greater China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(4), 363–377. doi:10.1080/01434632.2012.661435.

Freeman, C. (2009). Teaching business English using cases. Beijing: University of International Business and Economics.

Gao, Y. H., Cheng, Y., Zhao, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2005). Self-identity changes and English learning among Chinese undergraduates. World Englishes, 24(1), 39–51.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A. (1987). English for specific purposes: a learning centered approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jin, Y., & Yang, H. Z. (2006). The English Proficiency of College and University students in China: as reflected in the CET. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19(1), 21–36. doi:10.1080/07908310608668752.

Leaver, B. L., & Shekhtman, B. (2002). Principles and practices in teaching superior-level language skills: not just more of the same. In B. L. Leaver & B. Shekhtman (Eds.), Developing professional-level language proficiency (pp. 3–33). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Long, M. (2005). Chapter 1 Methodological issues in learner needs analysis. In M. Long (Ed.), Second language needs analysis (pp. 19–76). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moslehifara, M. A., & Ibrahim, N. A. (2012). English language oral communication needs at the workplace: feedback from human resource development (HRD) trainees. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 66, 529–536. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.297.

Şimon, S. (2014). Enhancing the English oral communication skills of the 1st year students of the Bachelor’s degree program “Communication and Public Relations”. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 2481–2484. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.596.

Stanley, P. (2011). 4 Meeting in the middle? Intercultural adaptation in tertiary oral English in China. In L. X. Jin & M. Cortazzi (Eds.), Researching Chinese learners: skills, perceptions and intercultural adaptations (pp. 93–118). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wang, L. F., & Li, L. (2011). Analysis of business foreign language disciplinary connotation and development path [Shang Wu Wai Yu de Xue Ke Nei Han yu Fa Zhan Lu Jing Fen Xi]. Foreign Language World, 6(147), 6–14.

Wang, L. F., Ye, X. G., Yan, M., Peng, Q. L., & Xu, D. J. (2015). Business English program teaching quality National standard interpretation [Shang Wu Ying Yu Zhuan Ye Ben Ke Jiao Xue Zhi Liang Guo Jia Biao Zhun Yao Dian Jie Du]. Foreign Language Teaching and Research (bimonthly), 47(2), 297–302.

West, R. (1994). Needs analysis in language teaching. Language Teaching, 27, 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0261444800007527.

Wette, R., & Barkhuizen, G. (2009). Teaching the book and educating the person: challenges for university English language teachers in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 29(2), 195–212. doi:10.1080/02188790902857180.

Wolff, M. (2009). Chapter 14 Incompatibility of corporate training and holistic English. In M. Wolff (Ed.), China EFL curriculum reform (pp. 255–258). New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.

Yang, J. (2006). Learners and users of English in China. English Today, 22(2), 3–10. doi:10.1017/S0266078406002021.

Zhang, L. L., & Wang, S. (2012). An empirical study on types of motivation in ESP learning among English majors. China ESP Journal, 3(1), 33–42.

Zhang, Y. Z. (2014). Business English Curriculum Development based on Needs Analysis [Ji Yu Xu Qiu Fen Xi de Shang Wu Ying Yu Ke Cheng She Zhi Yan Jiu]. China After School Education, 10, 102–103.

Zheng, L.H. (2011). Needs analysis of business English for English majors in Zhejiang University. Social Sciences Education, April, 35 - 36.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge the project support extended by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [2015ZX19]. The author would also like to express her great gratitude to the participants in the study for their warm support and contributions. Furthermore, the author thanks the anonymous reviewers for their expert suggestions in revising the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Q. Business Communication Needs of English Major Undergraduates and Curriculum Development in a Chinese University. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 25, 667–676 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0296-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-016-0296-z