Abstract

Background and Objective

Managed entry agreements (MEAs) consist of a set of instruments to reduce the uncertainty and the budget impact of new high-priced medicines; however, there are concerns. There is a need to critically appraise MEAs with their planned introduction in Brazil. Accordingly, the objective of this article is to identify and appraise key attributes and concerns with MEAs among payers and their advisers, with the findings providing critical considerations for Brazil and other high- and middle-income countries.

Methods

An integrative review approach was adopted. This involved a review of MEAs across countries. The review question was ‘What are the health technology MEAs that have been applied around the world?’ This review was supplemented with studies not retrieved in the search known to the senior-level co-authors including key South American markets. It also involved senior-level decision makers and advisers providing guidance on the potential advantages and disadvantages of MEAs and ways forward.

Results

Twenty-five studies were included in the review. Most MEAs included medicines (96.8%), focused on financial arrangements (43%) and included mostly antineoplastic medicines. Most countries kept key information confidential including discounts or had not published such data. Few details were found in the literature regarding South America. Our findings and inputs resulted in both advantages including reimbursement and disadvantages including concerns with data collection for outcome-based schemes.

Conclusions

We are likely to see a growth in MEAs with the continual launch of new high-priced and often complex treatments, coupled with increasing demands on resources. Whilst outcome-based MEAs could be an important tool to improve access to new innovative medicines, there are critical issues to address. Comparing knowledge, experiences, and practices across countries is crucial to guide high- and middle-income countries when designing their future MEAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Managed entry agreements are in operation around the world and they can be an important tool to address uncertainties related to new medicines/health technologies including their potential budget impact. |

Managed entry agreements can provide several benefits including reimbursing new medicines where this would have been difficult and managing increasing demand for medicines within available resources benefitting all countries. Decision makers should also consider their limitations and challenges before adopting different schemes including those with outcome-based schemes. |

This paper provides a worldwide vision of managed entry agreements including their advantages, disadvantages and key considerations to support decision makers for the future. |

1 Introduction

1.1 Rationale Behind Managed Entry Agreements (MEAs)

Providing efficient, safe, equitable and accessible health services to all citizens is the goal of many countries, especially those with universal healthcare systems [1, 2]. Initiatives and activities to achieve this goal across countries have been enhanced by the constant monitoring of their progress to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3, i.e. ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages [3, 4]. However, this is becoming more challenging with ageing populations across many countries, the increase in the prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases, the instigation of single disease model guidelines and policies, along with the continual launch of new higher priced medicines to address areas of unmet need [2, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. There are now concerns that even high-income countries are failing to provide high-quality services as resource pressures grow [17,18,19], leading to delays to their funding and utilisation [20,21,22]. This builds on the limited use of biological medicines to treat patients with immunological diseases among middle-income European countries vs higher income countries in view of their costs and co-payment issues [15, 23, 24]. Similarly, there is greater availability of cancer medicines and those for orphan diseases among higher income European countries vs lower income countries again owing to a number of reasons including issues of costs, affordability and other priority demands [25,26,27]. However, funding and co-payment concerns may be eased by the increasing availability of oral generic cancer medicines and biosimilars along with aggressive discounting by originator manufacturers to secure procurement and utilisation once originators lose their patents [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Currently, for instance, a course of standard treatment for early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer including doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel and trastuzumab would cost approximately 10 years of average annual wages in South Africa; however, costs are expected to fall appreciably with the availability of biosimilar trastuzumab alongside generic doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and docetaxel [27, 34, 35].

The increasing prevalence of patients with non-communicable diseases, with an associated increase in medicine use, as well as high requested prices for new medicines for patients with cancer and orphan diseases [36,37,38,39,40], has increased the focus on medicines and their expenditures in recent years. We have seen the price per life-year gained for new cancer medicines rising up to four-fold during the past years after adjusting for inflation [39, 41], alongside high requested prices for new medicines for orphan diseases [5, 40]. In view of this, coupled with increasing prevalence rates, expenditure on medicines for cancer now dominate pharmaceutical expenditure in high-income countries [42,43,44]. In Europe, total expenditure on medicines for cancer doubled from €14.6 billion in 2008 to €32 billion in 2018 (in 2018 prices and exchange rates) [45], with the cost of cancer care accounting for up to 30% of total hospital expenditure driven by the increasing cost of medicines [46,47,48]. Overall, worldwide sales of medicines for oncology are estimated to reach US$200 billion by 2022, up from US$133 billion in 2017, despite the increasing availability of biosimilars and low-cost oral generics [44]. There are also concerns with rising expenditure on medicines for orphan diseases with worldwide sales envisaged to be over US$178 billion in 2020 [8, 49, 50]; potentially offset by the increasing use and availability of low-cost generics and biosimilars [50].

The emotive nature of cancer and orphan diseases has enhanced their potential for funding and reimbursement in high-income countries at high prices despite the limited health gain of a number of new medicines [40, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. However, as mentioned, this has resulted in their variable and limited funding in lower income countries, similar to the situation seen with immunological diseases [15, 25, 26]. The focus on medicines can also distort funding decisions as seen with considerable funding for immunotherapeutic regimes in a number of middle-income countries; however, on average, only 22% of patients have access to safe, affordable and timely cancer surgery in these countries [58]. There is likely to be a similar challenges with funding new advanced therapy medicinal products, as well as regenerative medicines, given current requested prices, the number of these medicines in development and the degree of uncertainty surrounding them, which is leading to new models being proposed for their funding including performance-based annuity payments [13, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Typically, the decision to reimburse and fund new higher priced medicines is often hampered by numerous uncertainties that exist regarding their effectiveness, safety and cost effectiveness, as well as their potential budget impact in routine clinical care [2, 66,67,68,69]. This can cause concern especially in patients with cancer where there is a high failure rate with turning promising phase II data into positive findings in later studies, i.e. phase III and beyond [70,71,72,73,74,75]. Having said this, new medicines for patients with hepatitis C have achieved the desired reductions in viral loads and statins have achieved the desired reduction in cardiovascular events post-launch [76,77,78].

However, truly innovative and valued technologies are not necessarily receiving appropriate funding limiting patient access once launched [7, 15, 79, 80]. Potential methods to address this include creating budgetary space through encouraging the use of low-cost generics and biosimilars where pertinent, improving the competitiveness of the off-patent market for orphan drugs as more medicines for orphan diseases lose their patents building on examples in Europe including imatinib, which was initially launched as an orphan disease medicine, developing new models for pricing considerations especially for orphan diseases including multi-criteria decision models, which can also be used for priority setting, as well as developing fair pricing models [32, 56, 81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. There has also been a growth in managed entry agreements (MEAs) across countries to help with reimbursement and funding of new valued medicines. These agreements are principally aimed at enhancing the affordability and value of new medicines at launch and post-launch given their frequent substantial budget impact and clinical uncertainty in routine clinical care at the time of their launch [9, 18, 67, 69, 93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]. This is particularly the case for new medicines for oncology and orphan diseases [68, 93, 104, 110,111,112,113,114,115].

1.2 Definition of MEAs

According to Ferrario and Kanavos [94], MEAs typically consist of “a set of instruments used to reduce the impact of uncertainty and high prices when introducing a new medicine”, providing access to new typically higher priced, but considered cost-effective, technologies under pre-established conditions between both parties [67, 94, 97, 116]. Numerous terms have been used to describe such schemes, including risk-sharing arrangements, risk-sharing schemes, MEAs, managed entry schemes, performance-based risk-sharing schemes, performance-based risk-sharing arrangements, outcome-based MEAs, outcome-based contracting and patient access schemes [2, 5, 69, 95,96,97, 104, 117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124]. These agreements or schemes typically use different methodologies to reduce uncertainties related to the technology, especially its value and budget impact, and are typically tailored to a given situation and country [95, 121, 122, 125].

Managed entry agreements are now the generally used term rather than “risk-sharing scheme”. The Health Technology Assessment International society defines MEAs as “an arrangement between a manufacturer and payer or provider that enables coverage or reimbursement of a health technology subject to specific conditions” [69, 122, 126, 127]. According to the taxonomies developed by Adamski et al. [97], Ferrario et al. [93], the World Health Organization, and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, such agreements can be subdivided into payments that are linked to health outcomes or, alternatively, the financial considerations, where the price is defined considering quantitative measures such as the estimated consumption of the technology in question [68, 94, 97, 104, 121, 128,129,130]. The design of these agreements does differ across countries, suggesting that different cultures, systems and goals may require different programmes and approaches. However, the rationale is often similar. Table 1S of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) provides illustrative details of the different schemes and examples that have existed or are still ongoing across countries. Insurance companies in the USA are also now entering into value-based contracts with hospitals to share the risk [131].

1.3 Challenges and Benefits from MEAs

There is a general consensus that outcome-based schemes are more challenging than financial-based schemes in view of the necessary infrastructure involved [93, 96, 104, 112, 124, 125, 132]. There are also concerns whether outcome-based schemes actually achieve a shift in resource allocation to more effective medicines and/or patient populations [133]. This can potentially be seen with the use of surrogate markers in outcome-based schemes especially in patients with solid tumours as these may not necessarily translate into improved outcomes [53, 134,135,136,137]. Other concerns regarding outcome-based agreements include a belief that ending reimbursement when conditional schemes for new medicines fail to demonstrate the necessary value can be more difficult in practice than starting such schemes [138]. However, reimbursed prices are not increased when the value of a new medicine is shown to increase as more data become available. However, we believe such situations are rare in practice with phase II and III studies principally including selected patients compared with routine clinical care and there can be concerns with turning positive trends in surrogate markers into similar improvements in outcomes [53, 75, 136]. Principal concerns regarding financial-based agreements include the lack of transparency with respect to discounts and rebates [57, 93]. This is of critical concern among countries that rely on external reference pricing for their deliberations and where patient co-payments are based on list rather than discounted prices [57, 139]. Appropriate redaction of publicly available documents is one way forward in addition to growing calls for increased transparency [117, 140, 141]. There are concerns though with appropriate incentives for pharmaceutical companies if prices continue to fall and there is price fixing at lower costs with increased transparency [142]. However, increasing discussions regarding fair pricing approaches for new medicines will necessarily involve increased transparency [85, 86, 90, 143].

However, there can be considerable benefits with MEAs. These include reimbursing and funding new medicines where this would have been difficult to achieve; demonstrating negotiated outcomes can be achieved in practice, as seen with the statins in the UK and new medicines for hepatitis C in Sweden; only paying for agreed outcomes, as seen with new treatments for hypercholesterolaemia in USA; increasing the use of biomarkers to better target treatments and resources, as seen with medicines for multiple myeloma; and finally, keeping within agreed budgets through discounts and rebates [9, 76, 97, 106, 144, 145]. In Italy, there were concerns with the effectiveness of donepezil and other treatments for patients with Alzheimer’s disease when first launched, resulting initially in a 100% co-payment for these medicines [97]. However, a study undertaken among 500 Alzheimer Evaluation Units (CRONOS study) in Italy demonstrated a similar health gain in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease in routine care compared with those seen in the clinical trials, which resulted in the Italian National Health Service subsequently fully funding these medicines (‘A’ classification) provided patients were treated in specialist outpatients clinics [97, 146].

These examples of MEAs can be seen as part of a general approach within healthcare systems to monitor the effectiveness, safety and value of new medicines where possible especially where there are concerns initially with their effectiveness, safety and value in routine clinical care [144, 147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156]. In addition, there is a general movement from a policy model of one-time evaluation regarding the incorporation of a new technology into healthcare systems towards a model of multiple evaluations of new health technologies over time. Such activities are likely to grow with the emergence of electronic health records and information systems across countries [14, 157].

The potential savings in terms of cost avoidance from financial-based MEAs can be appreciable. In the Netherlands, savings from financial-based agreements in 2017 was €150 million and €203 million in 2018 [9], equating to 4.4% of total pharmaceutical sales in 2017 [158]. In Belgium, after adopting MEAs, the total extent of discounts under the various MEAs was €23.7 million in 2013 rising to €273.4 million in 2017, again equating to 4.4% of total pharmaceutical sales [158]. A similar situation was seen in France in 2015 where the following rebates occurred under agreed MEAs [9]:

-

Price–volume agreements: €573 million.

-

Budget caps (medicines for orphan diseases): €139 million.

-

Outcome-based agreements: €98 million.

-

Discounts: €94 million.

-

Cost/patient (based on an agreed treatment scheme and average daily costs): €82 million.

-

Others (not specified): €29 million.

In Colombia, the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection through the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) was able to make a centralised purchase for new treatments for hepatitis C cutting the price by nearly 80% [159]. By the end of October 2018, the centralised purchase had benefited 1069 patients with a healing rate of 96.2% [159]. In Brazil, the Ministry of Health recently published a performance evaluation guideline to provide continuous assessment of technologies incorporated in the National Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde-SUS) [160]. The first evaluation in the country was made for intramuscular beta interferon 1a, attesting its inferiority compared with other beta interferons already incorporated by the SUS [161].

1.4 Objectives of the Paper

In 2019, the Brazilian Minister of Health announced that a new modality of technology acquisition would be adopted through risk-sharing agreements for relevant high-price medicines [162, 163]. However, there was an identified need to learn from the experiences in other countries. As a result, we undertook a combined approach to provide guidance to the authorities in Brazil. This included an integrative review, documenting a range of international experiences with MEAs, along with information on MEAs from other South American countries. In addition, an appraisal of the principal issues and concerns among health authority personnel and their advisers from multiple countries, including middle-income countries, involved in the design and implementation of MEAs.

Consequently, the overall aim of this paper is to provide a basis for critical considerations surrounding the implementation of future performance-based agreements among the authorities in Brazil. Such considerations may also be pertinent for other middle- and higher-middle income countries going forward as they refine existing MEAs as well as appraise new MEAs for their markets.

2 Methods

2.1 Combined Approach

An integrative review approach was adopted to achieve the objective. The first stage involved a review of MEAs across countries. The review question was ‘What are the health technology managed entry agreements that have been applied around the world?’ We were aware that a number of reviews have been conducted and published regarding MEAs [93,94,95, 97, 104, 106, 164,165,166]; however, we wanted to consolidate these and expand them to include Latin America. This review was supplemented with published studies not retrieved in the search, coupled with other sources from the senior-level co-authors regarding ongoing arrangements within key South American markets (second stage), as only limited published information was found. The countries included Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Uruguay.

The third stage involved senior-level health authority personnel, their advisers and academics from a range of high- and middle-income countries involved with implementing and/or researching MEAs, coupled with senior-level personnel from PAHO and the World Bank, providing guidance on potential advantages and disadvantages, as well as key considerations that the authorities in Brazil should consider as they progress with MEAs. This was based on the literature review, combined with their own experiences and activities. The contextualising of the findings from the multiple approaches was principally from a payer (national or regional health authority or health insurance company) perspective, as this was the main emphasis of the paper.

This three-part approach was adopted because of the limited information regarding the implementation of MEAs and their impact, especially outcome-based schemes, available in the published literature [5, 9, 93, 94]. These combined approaches have been successfully used before when providing guidance and feedback to key stakeholder groups in disease areas and situations of interest [8, 83, 93, 97, 167,168,169,170,171,172].

2.2 Search Design for the Literature Review

Search strategies were designed for PubMed, EMBASE, LILACS and Cochrane Library databases on 5 March, 2019. The literature search used the strategy outlined by the Cochrane guideline, considering the population, intervention/exposure, comparator and, in some cases, the outcomes (clinical results) [PICO] [173]. This review considered: problems, topics of interest and outcomes:

-

Problem: MEAs;

-

Topic of interest: medicines or health technologies;

-

Outcomes: experiences, processes, performances and efficiency of MEAs.

Descriptors and words were extracted from the three main controlled vocabularies according to Cochrane, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for the MEDLINE database and others, including the Emtree thesaurus for EMBASE database and Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) for Latin America databases. Some synonyms and keywords were also added to the search on all text. The search strategies used in each database are detailed in Table 2S of the ESM.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Literature Review

This review included the following eligibility criteria for potential studies:

-

Inclusion papers in Portuguese, English or Spanish concerning payment for performance and/or risk-sharing agreements and/or MEAs experiences across countries and suppliers for medicines or health technologies, including systematic or integrative reviews, as well as abstracts published in annals.

-

Exclusion dissertations or theses; editorials; news; commentaries; letters to the editor; guidelines; and studies that did not identify the payment for performance/risk-sharing agreements/MEA.

The eligibility of potential studies was assessed by two researchers (MSC and ALP), using the Rayyan® web app. They undertook the initial screening of the studies by reading the titles and abstracts. Disagreements were solved by a third researcher (CZD). Subsequently, the articles selected were analysed by reading the full text. Articles were subsequently included in the review if they met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were assessed by a third reviewer (MMG). Grey literature was also considered as an important strategy to recover eligible studies in this review as we believed a number of MEAs may be contained in the grey literature and not published. This was conducted via a manual search of the references in the first selected papers, additional search in Google/Google academics, as well as with suggestions from the co-authors and others working in this field. Any conflict was also resolved by another researcher (CZD), who made the final decision.

2.4 Analysis of the Results from the Literature Review

The data extracted from the publications were analysed by country through a descriptive analysis approach. The variables considered were: year, type of agreement, type of technology/medicine, clinical condition, and the payers and providers involved. Relevant additional publications known to the co-authors that were not covered in the literature search were also included to add depth and robustness to the paper.

3 Results

3.1 Literature Review

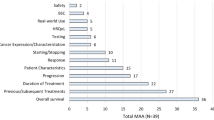

A systematic literature review conducted among the four databases retrieved 2299 articles. Seventy-four articles remained after removing duplicates and reading the titles and abstracts. After a full reading of the papers and the inclusion of manual and grey literature, 25 studies remained, addressing 446 agreements (Fig. 1 of the ESM).

Of these, 432 agreements included medicines and only 14 included other technologies or procedures. Most of the arrangements were financial, including discounts and volume (43%), followed by performance-based schemes (36%). More than half of the agreements involved antineoplastic medicines. Among the pharmaceutical companies involved in such arrangements, Novartis, Roche and Pfizer were the most cited. Table 3S of the ESM presents the main characteristics of the MEAs identified in the studies.

The agreement categories: “outcomes”, “impact results” and “other aspects” were typically not fully addressed in the included studies, which meant we could not deeply analyse the results and performance of the agreements. Most countries kept key information, such as discounts or rebates, confidential or have not published such data in journals or conferences [103, 106, 132]. This is a concern, particularly regarding publicly funded healthcare systems as this information cannot be used to guide pricing considerations in other countries as identified in a number of publications and reviews [5, 93, 174, 175]. Having said this, care is needed to still incentivise companies to invest in new medicines whilst maintaining the sustainability of healthcare systems [142]. Such deliberations will continue with growing calls for fair pricing for new medicines among key stakeholder groups [85, 90, 143, 176], with the World Health Organization arguing that improving price transparency should be encouraged on the grounds of good governance with no conclusive evidence on its downside [27]. Figure 2S of the ESM depicts which countries are already practicing MEAs, according to the literature.

3.2 Summary of Studies Broken Down by Continent and Country

Table 4S of the ESM provides the details of the MEAs among selected countries found from the literature review and supplemental data, building on the information presented in Table 3S of the ESM. Overall, we see financial-based MEAs as the principal type of MEA in a number of European countries. Until the end of 2015, in Poland, for example, the most common types of MEAs for new medicines included discounts (43.6%) and other schemes (34.5%), which typically involved free supplies and payback arrangements (21.8%). There were no outcome schemes in operation at this time [177].

By the end of 2018, there were over 100 MEAs established in the National Health Service Scotland that are part of the patient access schemes [119]. The vast majority were simple discount schemes (discount at the point of invoice). Less than 10% of the MEAs involved more complex financial schemes and only one was an outcome-based scheme. There are likely to be similar arrangements in England and Wales. However, the situation may change in the UK with criteria for ring-fencing monies to fund new cancer medicines where there are concerns with their cost effectiveness now changed with the requirement that new applications be part of an agreed managed access scheme that includes the collection of health service utilisation data to inform subsequent funding decisions alongside ongoing debates on this subject [178, 179].

In Canada, MEAs are principally financial-based schemes involving the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance for publicly funded drug programmes and patients [116]. Currently, outcome-based schemes are seen as challenging because of the lack of integrated real-world data sources in Canada [116]. As new medicines increasingly target niche populations, it may require data from more than one country to combine their real-world data to gain enough patients to assess meaningful findings [125, 180]. Table 5S of the ESM summarises the types of MEAs found in a number of different countries with a range of geographies, gross domestic product and financing of healthcare systems.

3.3 MEAs in Key South American Countries

The literature review retrieved scant information regarding agreements in South American countries. In this approach, when consulting other sources (suggested by co-authors from these countries) regarding ongoing arrangements within key South American markets, some activities, including planned agreements, and the funding of medicines were summarised (Table 1).

3.4 Key Considerations for MEAs from a Payer’s Perspective

There are a number of considerations that need to be carefully considered when starting MEAs, especially among middle-income countries. These can be divided into their potential advantages (Box 1) and disadvantages (Box 2), as well as key areas to consider during initial negotiations with pharmaceutical companies and their implementation (Box 3). These have been identified from the literature (Table 1 as well as Tables 1S, 3S and 4S of the ESM), supplemented by the considerable experiences of the co-authors. There is a concern though that middle-income countries will pay more for their medicines than higher income countries. This is because higher income countries potentially have greater economic power when discussing and debating confidential discounts and rebates in MEAs for new medicines [139, 185,186,187,188,189], potentially unbalancing the international market. However, we have seen purchasing consortia forming to address this as seen with PAHO and treatments for hepatitis C in South America [159]. A number of cross-border Pan-European Groups have now formed including BeNeLuxA, Nordic and Valletta groups undertaking joint activities including Horizon Scanning and health technology assessment activities [190,191,192,193], and these are likely to continue. However, joint reimbursement negotiations are at an earlier stage given differences between the reimbursement and legal systems in each country [194].

7 Discussion

Based on the literature review, 97% of MEAs identified involved medicines, typically medicines for oncology, with financial-based schemes the most prevalent. This is perhaps not surprising in view of the complexities typically involved in outcome-based schemes as well as the necessary infrastructure to undertake such schemes (Boxes 2 and 3). Moreover, in reality, financial-based schemes have been perceived as easier to undertake as seen by different recommendations by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in England and Wales for the different approaches [201]. In addition, financial-based agreements are generally seen as a more effective method whereby health services can monitor and influence their outlay on expensive medicines. However, this is not universal considering the developments in outcome-based contracting for medicines and diseases areas among managed care organisations in the USA (Table 1S of the ESM). In addition, the UK is now linking the collection of clinical data with funding for new oncology medicines within the cancer drug fund [178].

In our literature review, we found MEAs in most continents. In North America, the USA is notable for the large number of agreements particularly involving several payers (Tables 1S, 4S and 5S of the ESM). As mentioned, this high number of payers is related to the model of their health system with a considerable number of patients covered by different health insurance providers with 67.2% of patients currently covered by private insurance schemes in the USA and 37.7% by government coverage [202]. In South America, Marin et al. referred to Colombia as a pioneer in MEAs [203]. However, a greater understanding of the healthcare system in Colombia with its current challenges would appear to contradict this (Table 1). Whilst no studies were found in the literature review reporting Uruguayan experiences with MEAs, a number of these are now in operation (Table 1) [204]. In Oceania, both New Zealand and Australia have MEAs, and in Asia there are MEAs in existence in China, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, Korea and Taiwan [69, 101, 164].

There are a number of reasons why MEAs have now become widespread across countries. These include, as previously mentioned, progress in science involving more complex treatments. Reasons also include the launch of advanced therapies with typically high associated prices and an associated budget impact, uncertainty, and costs of new treatments as seen with new medicines for cancer and orphan diseases, and the increasing prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases with ageing populations with implications for appreciably increased use and costs of medicines [8, 39, 40, 61, 93, 205]. As a result, we are likely to see the number of MEAs grow alongside other potential measures for funding new medicines [8]. However, there are concerns that there is limited information to date regarding the results of MEAs to guide future activities [5, 9, 93, 99, 108]. This is complicated by the decision of many countries to preferentially adopt confidential discounts for new and existing medicines as part of any MEA especially within public healthcare systems. This has resulted in increasing calls for transparency; however, this has to be balanced against appropriate incentives for pharmaceutical companies to develop new medicines to address areas of unmet need as well as price fixing considerations [57, 93, 140, 142]. Moreover, the traditional methods of health technology assessment used to support decisions may not be enough by themselves in this context. As a result, more robust and innovative models including multicriteria decision analyses may be required to aid decision making, although there have been concerns with multicriteria decision analyses, which are being addressed [8, 91, 115, 206,207,208,209].

However, despite the many potential benefits of MEAs (Box 1), there are considerable concerns that need to be considered in countries such as Brazil as they seek to implement additional MEAs (Box 2). These include concerns with the extensive adoption of confidential price contracts. This means that no one country can really determine if they are getting optimal discounts compared with their neighbouring countries (Box 2). In addition, high-income countries with appreciable greater populations may use their economic power to negotiate aggressive confidential discounts, which may well not be available to smaller countries to the detriment of their citizens, especially if there are patient co-payments in the country. However, the number of outcome-based schemes may well grow to address uncertainty with a number of new medicines, especially in patients with cancer, being launched and approved by regulatory authorities on the basis of small clinical trials, with pressure on health authorities to fund them as more evidence is generated [75, 210].

Typically, a number of requirements are needed before MEAs can become a realistic option in middle-income countries. These include (i) a flexible legislative framework, (ii) an adequate infrastructure for data collection within the country to facilitate data entry and enhance the evaluation of all agreed schemes, (iii) potential for integration between the different current databases within a country to aid analysis, (iv) strengthening of current healthcare structures where pertinent to facilitate pertinent data entry and analysis as well as monitoring any agreement especially for outcome-based schemes, and (v) good alignment of the objectives between health authorities, clinicians and pharmaceutical companies including pertinent incentives for all key stakeholder groups. The outcome-based schemes, in particular, can be costly and necessitate in advance agreements regarding the funding for data entry, collection, analysis, medicines during data collection and supervision. Moreover, for allocation decisions, publicly funded healthcare systems need to consider reassessment of currently funded interventions and their value whenever new technologies enter the market [211].

Which type of MEA to choose when entering into negotiations with pharmaceutical and other companies, as well as the key factors to consider when developing these agreements, are part of a number of key issues that health authorities need to consider going forward (Box 3). This is particularly important in priority disease areas such as cancer and rare diseases as new medicines are typically needed in these areas but have commanded high prices despite often limited health gain [40, 55, 108, 212]. These agreements can be performed to improve scientific knowledge regarding new innovative technologies alongside providing early access to patients. However, this has to be balanced against issues of affordability and sustainability of the whole health system. New approaches or funding new medicines are, however, outside of the scope of this paper and may be followed up in future research projects [8]. Alternative access schemes for pharmaceuticals have also recently been collated and discussed by Löblová and colleagues [213], and such discussions will continue.

We are aware of the limitations of this paper regarding the formatting of data and the presentation of the results from the published articles owing to a lack of information regarding the nature of MEAs. This includes defining the parameters used in such agreements as well as the evaluation of the outcomes of any MEA. In addition, not all MEAs as well as not all countries with MEAs are included in this review due to publications not meeting the inclusion criteria. We are also aware that some agreements found in the literature are likely to have expired by now. However, they have been included as examples going forward especially in countries where there are limited outcome-based schemes to date. Despite these limitations, we believe our findings and their implications are robust providing direction to those planning MEAs.

8 Conclusions

We are likely to see a growth in MEAs in the future with the continual launch of new premium-priced medicines including new advanced therapy medicinal products. Alongside this, ageing societies demanding new complex treatments to address unmet needs further increase demands on available resources especially among high- and upper middle-income countries. Managed entry agreements are a potential way forward to address funding pressures alongside other financing approaches. However, MEAs can be complex to administer and require critical appraisal among all key stakeholders before initiation alongside issues of affordability and sustainability for the healthcare system as a whole. However, this has to be balanced against such agreements improving the knowledge base for new innovative technologies as well as providing early access to patients for potentially innovative therapies.

The financial-based agreements are easier to perform, enabling healthcare systems to reduce their outlay for new expensive medicines especially where there are considerable uncertainties surrounding the value of a new medicine in routine clinical care. Nevertheless, as mentioned, the extensive adoption of confidential price contracts across many countries generates market failures. Such discounts mean that no country can really determine if they are getting the best discounts jeopardising the overall goal of reducing the cost of new medicines. However, this has to be balanced against ensuring necessary incentives for companies to develop new technologies to address areas of unmet need. The specificities and peculiarities of each country should also be taken into account when seeking to initiate MEAs alongside adequate infrastructures. These include whether there are robust information systems in place for data collection rather than instigating single registries for each new medicine.

Managed entry agreements can potentially be important tools to improve the scientific capacity and knowledge within countries alongside providing access to new innovative and high-cost medicines whilst seeking to minimise the opportunity costs of the decisions. Incorporating international knowledge and practice can be a crucial strategy to guide countries such as Brazil as they design MEAs for new innovative medicines. We will be researching this further as Brazil starts to introduce MEAs.

Availability of Data and Material

Further data will be available on request.

References

Lieven A, Francis A, Olivier B, Kris B, Bogaert M, Stefaan C, et al. A call to make valuable innovative medicines accessible in the European Union. 2010. http://www.reesfrance.com/en/IMG/pdf/PlenaryII-Making-Innovative-Medicine-Accessible-in-the-EU.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2019.

INAMI. Outcomes based pricing and reimbursement of innovative medicines with budgetary limitations: discussion document for the multistakeholders meeting on pharmaceuticals (12th September 2017). https://www.inami.fgov.be/SiteCollectionDocuments/innovative_medicines_with_budgetary_limitations.docx. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

UN. Sustainable Development Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. 2019. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Morton S, Pencheon D, Squires N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and their implementation: a national global framework for health, development and equity needs a systems approach at every level. Br Med Bull. 2017;124(1):81–90.

WHO. Access to new medicines in Europe: technical review of policy initiatives and opportunities for collaboration and research. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/306179/Access-new-medicines-TR-PIO-collaboration-research.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Garattini S, Bertele V, Godman B, Haycox A, Wettermark B, Gustafsson LL. Enhancing the rational use of new medicines across European health care systems. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(12):1137–8.

Malmstrom RE, Godman BB, Diogene E, Baumgartel C, Bennie M, Bishop I, et al. Dabigatran: a case history demonstrating the need for comprehensive approaches to optimize the use of new drugs. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:39.

Godman B, Bucsics A, Vella Bonanno P, Oortwijn W, Rothe CC, Ferrario A, et al. Barriers for access to new medicines: searching for the balance between rising costs and limited budgets. Front Public Health. 2018;6:328.

KCE. How to improve the Belgian process for managed entry agreements? 2017. https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Download%20the%20synthesis%20in%20English%20%2840%20p.%29.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Lopes G, Vulto A, Wilking N, van Harten W, Meier K, Simoens S. Potential solutions for sustaining the costs of cancer drugs. Eur Oncol Haematol. 2017;13(2):102–7.

OECD. Health at a glance 2017. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/health_glance-2017-en.pdf?expires=1531413926&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=656327F799B10217DD2D80F463DAB8732017. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Schwarzer R, Rochau U, Saverno K, Jahn B, Bornschein B, Muehlberger N, et al. Systematic overview of cost-effectiveness thresholds in ten countries across four continents. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(5):485–504.

Eder C, Wild C. Technology forecast: advanced therapies in late clinical research, EMA approval or clinical application via hospital exemption. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1600939.

Jorgensen J, Mungapen L, Kefalas P. Data collection infrastructure for patient outcomes in the UK: opportunities and challenges for cell and gene therapies launching. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1573164.

Baumgart DC, Misery L, Naeyaert S, Taylor PC. Biological therapies in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: can biosimilars reduce access inequities? Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:279.

Oliveira MA, Luiza VL, Tavares NU, Mengue SS, Arrais PS, Farias MR, et al. Access to medicines for chronic diseases in Brazil: a multidimensional approach. Rev Saude Publica. 2016;50(Suppl. 2):6s.

Richards M, Thorlby R, Fisher R, Turton C. Unfinished business: an assessment of the national approach to improving cancer services in England 1995–2015. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2018/Unfinished-business-an-assessment-of-the-national-approach-to-improving-cancer-services-in-england-1995-2015.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Babar ZU, Gammie T, Seyfoddin A, Hasan SS, Curley LE. Patient access to medicines in two countries with similar health systems and differing medicines policies: implications from a comprehensive literature review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(3):231–43.

Pink GH, Brown AD, Studer ML, Reiter KL, Leatt P. Pay-for-performance in publicly financed healthcare: some international experience and considerations for Canada. Healthc Pap. 2006;6(4):8–26.

Kwon H-Y, Kim H, Godman B. Availability and affordability of drugs with a conditional approval by the European Medicines Agency; comparison of Korea with other countries and the implications. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:938.

IQVIA. EFPIA patient W.A.I.T. indicator 2018 survey. 2019. Available from: https://www.efpia.eu/media/412747/efpia-patient-wait-indicator-study-2018-results-030419.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Van Herck P, De Smedt D, Annemans L, Remmen R, Rosenthal MB, Sermeus W. Systematic review: effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:247.

Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK, Sokka T, Pavlova M, Uhlig T, et al. Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):198–206.

Kostic M, Djakovic L, Sujic R, Godman B, Jankovic SM. Inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis): cost of treatment in Serbia and the implications. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(1):85–93.

Wilking N, Bucsics A, Kandolf Sekulovic L, Kobelt G, Laslop A, Makaroff L, et al. Achieving equal and timely access to innovative anticancer drugs in the European Union (EU): summary of a multidisciplinary CECOG-driven roundtable discussion with a focus on Eastern and South-Eastern EU countries. ESMO Open. 2019;4(6):e000550.

EURODIS. Breaking the access deadlock to leave no one behind: a contribution by EURORDIS and its members on possibilities for patients’ full and equitable access to rare disease therapies in Europe. 2018. http://download2.eurordis.org.s3.amazonaws.com/positionpapers/eurordis_access_position_paper_final_4122017.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

WHO. Pricing of cancer medicines and its impacts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018: licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/277190/9789241515115-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Godman B, Allocati E, Moorkens E. Ever-evolving landscape of biosimilars in Canada; findings and implications from a global perspective. GABI J. 2019;8(3):93–7.

Sagonowsky E. AbbVie’s massive Humira discounts are stifling Netherlands biosimilars: report. 2019. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/abbvie-stifling-humira-biosim-competition-massive-discounting-dutch-report. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Davio K. After biosimilar deals, UK spending on adalimumab will drop by 75%. 2018. https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/news/after-biosimilar-deals-uk-spending-on-adalimumab-will-drop-by-75. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Derbyshire M, Shina S. Patent expiry dates for biologicals: 2017 update. GaBI J. 2018;7(1):29–34.

Godman B, Hill A, Simoens S, Kurdi A, Gulbinovič J, Martin AP, et al. Pricing of oral generic cancer medicines in 25 European countries; findings and implications. GaBI J. 2019;8(2):49–70.

Ferrario A, Dedet G, Humbert T, Vogler S, Suleman F, Pedersen HB. Strategies to achieve fairer prices for generic and biosimilar medicines. BMJ. 2020;368:l5444.

Pegram MD, Bondarenko I, Zorzetto MMC, Hingmire S, Iwase H, Krivorotko PV, et al. PF-05280014 (a trastuzumab biosimilar) plus paclitaxel compared with reference trastuzumab plus paclitaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(2):172–82.

Blackwell K, Gligorov J, Jacobs I, Twelves C. The global need for a trastuzumab biosimilar for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(2):95–113.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf;jsessionid=89D7CBFF5B60AE5394BEAB3AFD48A501?sequence=1. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Gyasi RM, Phillips DR. Aging and the rising burden of noncommunicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa and other low- and middle-income countries: a call for holistic action. Gerontologist. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz102.

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59.

Howard DH, Bach P, Berndt ER, Conti RM. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(1):139–62.

Luzzatto L, Hyry HI, Schieppati A, Costa E, Simoens S, Schaefer F, et al. Outrageous prices of orphan drugs: a call for collaboration. Lancet. 2018;392(10149):791–4.

Bach PB, Saltz LB. Raising the dose and raising the cost: the case of pembrolizumab in lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx125.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Global oncology trend report a review of 2015 and outlook to 2020. June 2016. https://www.scribd.com/document/323179495/IMSH-Institute-Global-Oncology-Trend-2015-2020-Report. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. Global oncology trends 2018. https://www.iqvia.com/institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2018. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Hofmarcher T, Brådvik G, Svedman C, Lindgren P, Jönsson B, Wilking N. Comparator report on cancer in Europe 2019: disease burden, costs and access to medicines. Lund: IHE Report 2019:7. https://www.efpia.eu/media/413449/comparator-report-on-cancer-in-europe-2019.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

van Harten WH, Wind A, de Paoli P, Saghatchian M, Oberst S. Actual costs of cancer drugs in 15 European countries. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):18–20.

Simoens S, van Harten W, Lopes G, Vulto A, Meier K, Wilking N. What happens when the cost of cancer care becomes unsustainable. Eur Oncol Haematol. 2017;13(2):108–13.

Wilking N, Lopes G, Meier K, Simoens S, van Harten W, Vulto A. Can we continue to afford access to cancer treatment? Eur Oncol Haematol. 2017;13(2):114–9.

Brau R, Tzeng I. Orphan drug commercial models. https://www.lifescienceleader.com/doc/orphan-drug-commercial-models-0001. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Palaska C, Kelly T, Hutchings A, Parnaby A. An analysis of orphan medicine expenditure in Europe: is it sustainable? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):287.

Haycox A. Why cancer? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):625–7.

Simoens S, Picavet E, Dooms M, Cassiman D, Morel T. Cost-effectiveness assessment of orphan drugs: a scientific and political conundrum. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(1):1–3.

Kantarjian HM, Fojo T, Mathisen M, Zwelling LA. Cancer drugs in the United States: justum pretium: the just price. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3600–4.

Cohen JP, Felix A. Are payers treating orphan drugs differently? J Market Access Health Policy. 2014;2(1):23513.

Cohen D. Cancer drugs: high price, uncertain value. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2017;359:j4543.

Godman B, Wild C, Haycox A. Patent expiry and costs for anti-cancer medicines for clinical use. Generics Biosimilars Initiative J. 2017;6(3):105–6.

Garattini L, Freemantle N. Comment on: ‘NICE, in confidence: an assessment of redaction to obscure confidential information in single technology appraisals by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(1):121–2.

Sullivan R, Pramesh CS, Booth CM. Look beyond technology in cancer care. Nature. 2017;549:325–8.

Hanna E, Toumi M, Dussart C, Borissov B, Dabbous O, Badora K, et al. Funding breakthrough therapies: a systematic review and recommendation. Health Policy. 2018;122(3):217–29.

Yu TTL, Gupta P, Ronfard V, Vertès AA, Bayon Y. Recent progress in European advanced therapy medicinal products and beyond. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018;6:130.

Jönsson B, Hampson G, Michaels J, Towse A, von der Schulenburg JMG, Wong O. Advanced therapy medicinal products and health technology assessment principles and practices for value-based and sustainable healthcare. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(3):427–38.

Barlow JF, Yang M, Teagarden JR. Are payers ready, willing, and able to provide access to new durable gene therapies? Value Health. 2019;22(6):642–7.

Jørgensen J, Kefalas P. Annuity payments can increase patient access to innovative cell and gene therapies under England’s net budget impact test. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2017;5(1):1355203.

Hampson G, Towse A, Pearson SD, Dreitlein WB, Henshall C. Gene therapy: evidence, value and affordability in the US health care system. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(1):15–28.

MIT NEWDIGS FoCUS Project. Designing financial solutions to ensure affordable access to cures: an overview of the MIT FoCUS project. 2018. https://newdigs.mit.edu/sites/default/files/NEWDIGS%20FoCUS%20Frameworks%2020180823.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E, Poplavska E, Pinto A, Aggarwal A. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009-13. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2017;359:j4530.

Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Dealing with uncertainty and high prices of new medicines: a comparative analysis of the use of managed entry agreements in Belgium, England, the Netherlands and Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:39–47.

Morel T, Arickx F, Befrits G, Siviero P, van der Meijden C, Xoxi E, et al. Reconciling uncertainty of costs and outcomes with the need for access to orphan medicinal products: a comparative study of managed entry agreements across seven European countries. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:198.

Robinson MF, Mihalopoulos C, Merlin T, Roughead E. Characteristics of managed entry agreements in Australia. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018;34(1):46–55.

Grignolo A, Pretorius S. Phase III trial failures, costly but preventable. Appl Clin Trials. 2016. https://www.parexel.com/application/files_previous/5014/7274/5573/ACT_Article.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Amiri-Kordestani L, Fojo T. Why do phase III clinical trials in oncology fail so often? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(8):568–9.

Gyawali B, Addeo A. Negative phase 3 randomized controlled trials: why cancer drugs fail the last barrier? Int J Cancer. 2018;143(8):2079–81.

Walter RB, Appelbaum FR, Tallman MS, Weiss NS, Larson RA, Estey EH. Shortcomings in the clinical evaluation of new drugs: acute myeloid leukemia as paradigm. Blood. 2010;116(14):2420–8.

Jonker DJ, Nott L, Yoshino T, Gill S, Shapiro J, Ohtsu A, et al. Napabucasin versus placebo in refractory advanced colorectal cancer: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(4):263–70.

Pontes C, Zara C, Torrent-Farnell J, Obach M, Nadal C, Vella-Bonanno P, et al. Time to review authorisation and funding for new cancer medicines in Europe? Inferences from the case of olaratumab. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(1):5–16.

Frisk P, Aggefors K, Cars T, Feltelius N, Loov SA, Wettermark B, et al. Introduction of the second-generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in chronic hepatitis C: a register-based study in Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(7):971–8.

Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1383–9.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7–22.

Liao JM, Fischer MA. Restrictions of hepatitis C treatment for substance-using Medicaid patients: cost versus ethics. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):893–9.

Douglass CH, Pedrana A, Lazarus JV, ‘t Hoen EFM, Hammad R, Leite RB, et al. Pathways to ensure universal and affordable access to hepatitis C treatment. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):175.

Kesselheim AS, Myers JA, Solomon DH, Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Avorn J. The prevalence and cost of unapproved uses of top-selling orphan drugs. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31894.

Godman B, Bucsics A, Burkhardt T, Haycox A, Seyfried H, Wieninger P. Insight into recent reforms and initiatives in Austria: implications for key stakeholders. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(4):357–71.

Godman B, Wettermark B, van Woerkom M, Fraeyman J, Alvarez-Madrazo S, Berg C, et al. Multiple policies to enhance prescribing efficiency for established medicines in Europe with a particular focus on demand-side measures: findings and future implications. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:106.

Moorkens E, Vulto AG, Huys I, Dylst P, Godman B, Keuerleber S, et al. Policies for biosimilar uptake in Europe: an overview. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0190147.

AIM. AIM proposes to establish a European drug pricing model for fair and transparent prices for accessible pharmaceutical innovations. https://www.aim-mutual.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/AIMs-proposal-for-fair-and-transparent-prices-for-pharmaceuticals.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Moon S, Mariat S, Kamae I, Pedersen HB. Defining the concept of fair pricing for medicines. BMJ. 2020;368:l4726.

Seixas BV, Dionne F, Conte T, Mitton C. Assessing value in health care: using an interpretive classification system to understand existing practices based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):560.

Mitton C, Seixas BV, Peacock S, Burgess M, Bryan S. Health technology assessment as part of a broader process for priority setting and resourceaAllocation. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(5):573–6.

Moreno-Calderón A, Tong TS, Thokala P. Multi-criteria decision analysis software in healthcare priority setting: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(3):269–83.

Uyl-de Groot CA, Lowenberg B. Sustainability and affordability of cancer drugs: a novel pricing model. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(7):405–6.

Lasalvia P, Prieto-Pinto L, Moreno M, Castrillon J, Romano G, Garzon-Orjuela N, et al. International experiences in multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) for evaluating orphan drugs: a scoping review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(4):409–20.

Guarga L, Badia X, Obach M, Fontanet M, Prat A, Vallano A, et al. Implementing reflective multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) to assess orphan drugs value in the Catalan Health Service (CatSalut). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):157.

Ferrario A, Arāja D, Bochenek T, Čatić T, Dankó D, Dimitrova M, et al. The implementation of managed entry agreements in Central and Eastern Europe: findings and implications. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(12):1271–85.

Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Managed entry agreements for pharmaceuticals: the European experience. EMiNet, Brussels, Belgium. 2013. Available from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50513/. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Carlson JJ, Chen S, Garrison LP Jr. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements: an updated international review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(10):1063–72.

Piatkiewicz TJ, Traulsen JM, Holm-Larsen T. Risk-sharing agreements in the EU: a systematic review of major trends. Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;2(2):109–23.

Adamski J, Godman B, Ofierska-Sujkowska G, Osinska B, Herholz H, Wendykowska K, et al. Risk sharing arrangements for pharmaceuticals: potential considerations and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:153.

Clopes A, Gasol M, Cajal R, Segu L, Crespo R, Mora R, et al. Financial consequences of a payment-by-results scheme in Catalonia: gefitinib in advanced EGFR-mutation positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Med Econ. 2017;20(1):1–7.

Goble JA, Ung B, van Boemmel-Wegmann S, Navarro RP, Parece A. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements: U.S. payer experience. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(10):1042–52.

Yoo SL, Kim DJ, Lee SM, Kang WG, Kim SY, Lee JH, et al. Improving patient access to new drugs in South Korea: evaluation of the National Drug Formulary System. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):288.

Choi MH, Ghosh W, Brooks-Rooney C. The impact of risk-sharing agreements on drug reimbursement decisions in South Korea. Value Health. 2018;21(Suppl. 2):S57.

Brown JD, Sheer R, Pasquale M, Sudharshan L, Axelsen K, Subedi P, et al. Payer and pharmaceutical manufacturer considerations for outcomes-based agreements in the United States. Value Health. 2018;21(1):33–40.

Milstein R, Schreyoegg J. Pay for performance in the inpatient sector: a review of 34 P4P programs in 14 OECD countries. Health Policy. 2016;120(10):1125–40.

Lu CY, Lupton C, Rakowsky S, Babar ZU, Ross-Degnan D, Wagner AK. Patient access schemes in Asia-pacific markets: current experience and future potential. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2015;8(1):6.

Darba J, Ascanio M. The current performance-linked and risk sharing agreement scene in the Spanish region of Catalonia. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(6):743–8.

Nazareth T, Ko JJ, Sasane R, Frois C, Carpenter S, Demean S, et al. Outcomes-based contracting experience: research findings from U.S. and European stakeholders. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(10):1018–26.

Araja D, Kõlves K. Managed entry agreements for new medicines in the Baltic countries. Eurohealth. 2016;22(1):27–30.

Godman B, Oortwijn W, de Waure C, Mosca I, Puggina A, Specchia ML, et al. Links between pharmaceutical R&D models and access to affordable medicines: a study for the ENVI Committee. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/587321/IPOL_STU(2016)587321_EN.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Ghinea H, Kerridge I, Lipworth W. If we don’t talk about value, cancer drugs will become terminal for health systems. http://theconversation.com/if-we-dont-talk-about-value-cancer-drugs-will-become-terminal-for-health-systems-44072. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Pauwels K, Huys I, Vogler S, Casteels M, Simoens S. Managed entry agreements for oncology drugs: lessons from the European experience to inform the future. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:171.

Kim ES, Kim JA, Lee EK. National reimbursement listing determinants of new cancer drugs: a retrospective analysis of 58 cancer treatment appraisals in 2007-2016 in South Korea. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(4):401–9.

Van de Vijver I, Quanten A, Knappenberg V, Arickx F, De Ridder R. Success and failure of straightforward versus sophisticated managed entry agreements. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A499.

Quanten A, Van de Vijver I, Knappenberg V, Arickx F, De Ridder R. Insights from 6 years’ managed entry agreement experience in Belgium. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A499.

Campillo-Artero C, del Llano J, Poveda JL. Risk sharing agreements: with orphan drugs? [in Spanish]. Farm Hosp. 2012;36(6):455–63.

Sola-Morales O, Volmer T, Mantovani L. Perspectives to mitigate payer uncertainty in health technology assessment of novel oncology drugs. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1562861.

Morse GN. Pharmaceutical managed entry agreements: lessons learned from Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia. https://morseconsulting.ca/pharmaceutical-managed-entry-agreements-lessons-learned/. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Bullement A, Taylor M, McMordie ST, Waters E, Hatswell AJ. NICE, in confidence: an assessment of redaction to obscure confidential information in single technology appraisals by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(11):1383–90.

Tuffaha HW, Scuffham PA. The Australian managed entry scheme: are we getting it right? Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(5):555–65.

NHS Scotland. Patient access scheme (PAS) guidance. November 2018. https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/media/3928/nhs-scotland-patient-access-scheme-pas-guidance-v70.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Makady A, van Veelen A, de Boer A, Hillege H, Klungel OH, Goettsch W. Implementing managed entry agreements in practice: the Dutch reality check. Health Policy. 2019;123(3):267–74.

Grimm SE, Strong M, Brennan A, Wailoo AJ. The HTA risk analysis chart: visualising the need for and potential value of managed entry agreements in health technology assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(12):1287–96.

Klemp M, Fronsdal KB, Facey K. What principles should govern the use of managed entry agreements? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(1):77–83.

Annemans L, Panie L. Dynamic outcomes based approaches to pricing and reimbursement of innovative medicines. 2017. https://www.eurordis.org/sites/default/files/FIPRA.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Catapult. Cell and gene therapy: enabling outcomes-based reimbursement through a universal platform for outcomes data. 2019. https://ct.catapult.org.uk/case-study/enabling-outcomes-based-reimbursement-through-universal-platform-outcomes-data?_cldee = ZXdhbi5tb3JyaXNvbkBuaHMubmV0&recipientid = contact-64c168729c5ae8118140e0071b6ee581-1b8c25455c8b44c5ba52f2d26432e9bd&utm_source=ClickDimensions&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Monthly%20newsletters&esid=c8f55ab4-ebad-e911-a972-000d3a38ad05. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Bouvy JC, Sapede C, Garner S. Managed entry agreements for pharmaceuticals in the context of adaptive pathways in Europe. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:280.

Castro HE, Kumar R, Malpica-Llanos T, et al. Sharing knowledge on innovative medicines for non-communicable disease: a compendium of good practices for sustainable access: promoting a dialogue among payers and manufacturers. 2018. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/792561542818915277/MSH-RTI-GLOHI-Compendium-Final-Version-2-Nov-21-2018.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Van Wilder P, Pirson M, Dupont A. Impact of health technology assessment and managed entry schemes on reimbursement decisions of centrally authorised medicinal products in Belgium. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75(7):895–900.

Yeung K, Li M, Carlson JJ. Using performance-based risk-sharing arrangements to address uncertainty in indication-based pricing. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(10):1010–5.

Carlson JJ, Sullivan SD, Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Veenstra DL. Linking payment to health outcomes: a taxonomy and examination of performance-based reimbursement schemes between healthcare payers and manufacturers. Health Policy. 2010;96(3):179–90.

Antonanzas F, Juarez-Castello C, Lorente R, Rodriguez-Ibeas R. The use of risk-sharing contracts in healthcare: theoretical and empirical assessments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(12):1469–83.

LaPointe J. Hospitals, Blue Cross NC share risk with new value-based contract. 2019. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/hospitals-blue-cross-nc-share-risk-with-new-value-based-contract. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Garattini L, Curto A. Performance-based agreements in Italy: ‘trendy outcomes’ or mere illusions? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(10):967–9.

Seeley E, Kesselheim AS. Outcomes-based pharmaceutical contracts: an answer to high U.S. drug spending? Issue Brief. 2017; pp/ 1–8.

Toumi M, Jaroslawski S, Sawada T, Kornfeld A. The use of surrogate and patient-relevant endpoints in outcomes-based market access agreements: current debate. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(1):5–11.

Prasad V, Kim C, Burotto M, Vandross A. The strength of association between surrogate end points and survival in oncology: a systematic review of trial-level meta-analyses. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1389–98.

Wild C, Grossmann N, Bonanno PV, Bucsics A, Furst J, Garuoliene K, et al. Utilisation of the ESMO-MCBS in practice of HTA. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(11):2134–6.

Paoletti X, Lewsley LA, Daniele G, Cook A, Yanaihara N, Tinker A, et al. Assessment of progression-free survival as a surrogate end point of overall survival in first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1918939.

van de Wetering EJ, van Exel J, Brouwer WB. The challenge of conditional reimbursement: stopping reimbursement can be more difficult than not starting in the first place! Value Health. 2017;20(1):118–25.

Leopold C, Vogler S, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, de Joncheere K, Leufkens HG, Laing R. Differences in external price referencing in Europe: a descriptive overview. Health Policy. 2012;104(1):50–60.

WHO. Improving the transparency of markets for medicines, vaccines, and other health products (footnote): draft resolution proposed by Andorra, Brazil, Egypt, Eswatini, Greece, India, Italy, Kenya, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Malta, Portugal, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Uganda. 2019. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_ACONF2Rev1-en.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

World Health Assembly. Improving the [access to (Germany)]/[transparency [in access (France)]/[of markets (DEL France)] for (DEL Germany)] medicines, vaccines and other health-related [products and (India)] technologies to be discussed at the 72nd session of the WHA to be held on 20-28 May 2019. https://www.healthpolicy-watch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/WHA-Resolution_DRAFT_10May1740.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Shaw B, Mestre-Ferrandiz J. Talkin’ about a resolution: issues in the push for greater transparency of medicine prices. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(2):125–34.

Suleman F, Low M, Moon S, Morgan SG. New business models for research and development with affordability requirements are needed to achieve fair pricing of medicines. BMJ. 2020;368:l4408.

Eldred K. Cigna’s two new value-based vontracts with Pharma for PCSK9 inhibitor cholesterol drugs tie financial terms to improved customer health. 2016. https://www.cigna.com/newsroom/news-releases/2016/cignas-two-new-value-based-contracts-with-pharma-for-pcsk9-inhibitor-cholesterol-drugs-tie-financial-terms-to-improved-customer-health. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Cole A, Cubi-Molla P, Pollard J, Sim D, Sullivan R, Sussex J, Lorgelly P. Making outcome-based payment a reality in the NHS. 2019. file:///C:/Users/mail/Downloads/Cole%20et%20al.%20Making%20Outcome-Based%20Payment%20a%20Reality%20in%20the%20NHS.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Bianchetti A, Ranieri P, Margiotta A, Trabucchi M. Pharmacological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18(2):158–62.

Godman B, Malmstrom RE, Diogene E, Jayathissa S, McTaggart S, Cars T, et al. Dabigatran: a continuing exemplar case history demonstrating the need for comprehensive models to optimize the utilization of new drugs. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:109.

Mueller T, Alvarez-Madrazo S, Robertson C, Wu O, Bennie M. Comparative safety and effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation in clinical practice in Scotland. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(2):422–31.

Maura G, Pariente A, Alla F, Billionnet C. Adherence with direct oral anticoagulants in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation new users and associated factors: a French nationwide cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(11):1367–77.

Kemp-Casey A, Pratt N, Ramsay E, Roughead EE. Using post-market utilisation analysis to support medicines pricing policy: an Australian case study of aflibercept and ranibizumab use. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(3):411–7.

Gomes RM, Barbosa WB, Godman B, Costa JO, Ribeiro Junior NG, Simão Filho C, et al. Effectiveness of maintenance immunosuppression therapies in a matched-pair analysis cohort of 16 years of renal transplant in the Brazilian National Health System. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):1974.

Dos Santos JB, Almeida AM, Acurcio FA, de Oliveira Junior HA, Kakehasi AM, Guerra Junior AA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adalimumab and etanercept for rheumatoid arthritis in the Brazilian Public Health System. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(6):539–49.

Alvarez-Madrazo S, Kavanagh K, Siebert S, Semple Y, Godman B, Maciel Almeida A, et al. Discontinuation, persistence and adherence to subcutaneous biologics delivered via a homecare route to Scottish adults with rheumatic diseases: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e027059.

Raaschou P, Simard JF, Holmqvist M, Askling J. Rheumatoid arthritis, anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy, and risk of malignant melanoma: nationwide population based prospective cohort study from Sweden. BMJ. 2013;346:f1939.

Raaschou P, Simard JF, Asker Hagelberg C, Askling J. Rheumatoid arthritis, anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment, and risk of squamous cell and basal cell skin cancer: cohort study based on nationwide prospectively recorded data from Sweden. BMJ. 2016;352:i262.

Garcia-Doval I, Cohen AD, Cazzaniga S, Feldhamer I, Addis A, Carretero G, et al. Risk of serious infections, cutaneous bacterial infections, and granulomatous infections in patients with psoriasis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents versus classic therapies: prospective meta-analysis of Psonet registries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):299–308.e16.

Jorgensen J, Kefalas P. Upgrading the SACT dataset and EBMT registry to enable outcomes-based reimbursement in oncology in England: a gap analysis and top-level cost estimate. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1635842.

OECD. Stat, pharmaceutical market. 2018. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_PHMC#. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Ministry of Health Columbia. Avances en la estrategia de negociación y compra centralizada de medicamentos para la hepatitis C. 2018. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/MET/fact-sheet-hepatitisc.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Gestão e Incorporação de Tecnologias em Saúde. Diretrizes metodológicas: avaliação de desempenho de tecnologias em saúde [recurso eletrônico]/Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos, Departamento de Gestão e Incorporação de Tecnologias em Saúde. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017;45: p. il.

Lemos LLP, Guerra Junior AA, Santos M, Magliano C, Diniz I, Souza K, et al. The assessment for disinvestment of intramuscular interferon beta for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Brazil. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(2):161–73.

Ministério da Saúde. Portaria No. 24, 24 April 2019. Torna pública a decisão de incorporar o nusinersena para atrofia muscular espinhal (AME) 5q tipo I, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde-SUS. 25 April 2019. Seção 1, No. 79.

Ministério da Saúde. Portaria No. 1. 297, 11 June 2019. Institui projeto piloto de acordo de compartilhamento de risco para incorporação de tecnologias em saúde, para oferecer acesso ao medicamento Spinraza (Nusinersena) para o tratamento da Atrofia Muscular Espinhal (AME 5q) tipos II e III no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde: SUS. Diário Oficial da União Seção 1, ISSN 1677-7042 No. 112, quarta-feira, 12 June 2019.

Coulton L, Annemans L, Carter R, Herrera MB, Thabrany H, Lim J, et al. Outcomes-based risk-sharing schemes: is there a potential role in the Asia-Pacific markets? Health Outcomes Res Med. 2012;3(4):e205–19.

Yu JS, Chin L, Oh J, Farias J. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements for pharmaceutical products in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(10):1028–40.

Garrison LP Jr, Towse A, Briggs A, de Pouvourville G, Grueger J, Mohr PE, et al. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements-good practices for design, implementation, and evaluation: report of the ISPOR good practices for performance-based risk-sharing arrangements task force. Value Health. 2013;16(5):703–19.

Godman B, Basu D, Pillay Y, Mwita JC, Rwegerera GM, Anand Paramadhas BD, et al. Review of ongoing activities and challenges to improve the care of patients with type 2 diabetes across Africa and the implications for the future. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:108.

Godman B, Malmstrom RE, Diogene E, Gray A, Jayathissa S, Timoney A, et al. Are new models needed to optimize the utilization of new medicines to sustain healthcare systems? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8(1):77–94.

Godman B, Finlayson AE, Cheema PK, Zebedin-Brandl E, Gutierrez-Ibarluzea I, Jones J, et al. Personalizing health care: feasibility and future implications. BMC Med. 2013;11:179.

Vella Bonanno P, Ermisch M, Godman B, Martin AP, Van Den Bergh J, Bezmelnitsyna L, et al. Adaptive pathways: possible next steps for payers in preparation for their potential implementation. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:497.

Guerra-Junior AA, de Lemos PLL, Godman B, Bennie M, Osorio-de-Castro CGS, Alvares J, et al. Health technology performance assessment: real-world evidence for public healthcare sustainability. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(2):279–87.

Godman B, McCabe H, Leong T, et al. Fixed dose drug combinations: are they pharmacoeconomically sound? Findings and implications especially for lower- and middle-income countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20(1):1–26.

Green S, Higgins JPT, Alderson P, Clarke M, Mulrow CD, Oxman AD. Chapter 1: introduction. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

Vogler S, Paris V, Ferrario A, Wirtz VJ, de Joncheere K, Schneider P, et al. How can pricing and reimbursement policies improve affordable access to medicines? Lessons learned from European countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(3):307–21.

Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Ferrario A, Wirtz VJ, de Joncheere K, Pedersen HB, et al. Pharmaceutical policies in a crisis? Challenges and solutions identified at the PPRI Conference. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9:9.

WHO. Fair pricing forum 2017 meeting report. 2017. https://www.who.int/medicines/access/fair_pricing/FairPricingForum2017MeetingReport.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.