Abstract

Background

The growing focus on patient-centred care has encouraged the inclusion of patient and public input into payer drug reimbursement decisions. Yet, little is known about patient/public priorities for funding high-cost medicines, and how they compare to payer priorities applied in public funding decisions for new cancer drugs.

Objectives

The aim was to identify and compare the funding preferences of cancer patients and the general public against the criteria used by payers making cancer drug funding decisions.

Methods

A thorough review of the empirical, peer-reviewed English literature was conducted. Information sources were PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Business Source Complete, and EconLit. Eligible studies (1) assessed the cancer drug funding preferences of patients, the general public or payers, (2) had pre-defined measures of funding preference, and (3) had outcomes with attributes or measures of ‘value’. The quality of included studies was evaluated using a health technology assessment-based assessment tool, followed by extraction of general study characteristics and funding preferences, which were categorized using an established WHO-based framework.

Results

Twenty-five preference studies were retrieved (11 quantitative, seven qualitative, seven mixed-methods). Most studies were published from 2005 onward, with the oldest dating back to 1997. Two studies evaluated both patient and public perspectives, giving 27 total funding perspectives (41 % payer, 33 % public, 26 % patients). Of 41 identified funding criteria, payers consider the most (35), the general public considers fewer (23), and patients consider the fewest (12). We identify four unique patient criteria: financial protection, access to medical information, autonomy in treatment decision making, and the ‘value of hope’. Sixteen countries/jurisdictions were represented.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that (1) payers prioritize efficiency (health gains per dollar), while citizens (patients and the general public) prioritize equity (equal access to cancer medicines independent of cost or effectiveness), (2) citizens prioritize few criteria relevant to payers, and (3) citizens prioritize several criteria not considered by payers. This can explain why payer and citizen priorities clash when new cancer medicines are denied public funding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Empirical research regarding citizens’ preferences for cancer drug funding is recent and developing, and can provide payers with important information about how patients and the general public value cancer medicines. |

Information about how the values of patients and the general public are included and used in funding decisions is also scant; understanding stakeholders’ values could be improved by payers sharing the patient and public input collected. |

More information sharing between payers and citizens can improve understanding of values and priorities, and has the potential to improve alignment between payer and citizen notions of ‘value’, which in turn can improve decision making and create greater value in healthcare systems. |

Where improved understanding does not improve alignment, agreement will need to be fostered on the basis of a process, rather than an outcome. |

1 Introduction

All societies face growing demands for healthcare, because of aging populations, rising prevalence of chronic diseases, increasing patient demand, and the higher cost of new medical technologies [1]. As resources are limited, priority setting is required. To control costs, many payers apply evidence-based principles in evaluating new medicines, often using ‘cost per unit of health outcome’ to measure ‘value for money’ [2].

The recent rise of patient-centred medicine emphasizes consumer-focussed measures of health system performance, including the integration of patient-relevant treatment outcomes in clinical and public access decisions [3, 4]. In countries with publicly funded pharmaceutical programmes, cost-based funding rejections for new cancer medicines have been contentious, and often the subject of patient group campaigns for coverage [5, 6]. Some have suggested that government priority-setting approaches are inadequate, and could be improved by including citizen (patient and public) input [7, 8]. Challenges in balancing funding and access are especially evident in cancer, where new technologies are providing a surge of innovative therapies, extending survival rates and providing more options to patients. With global cancer rates projected to double by 2030, one in three people in developed countries will experience cancer in their lifetime (one in two in the UK), and, therefore, the number of patients seeking to access care is also expected to rise [9, 10]. Oncology drug costs have become a particular battleground, having reached US$100 billion in 2014, and representing 10.8 % of total global drug spending, most of which remains concentrated in the five largest European countries and the USA [11]. The use of social media and online networks are expected to facilitate patient engagement throughout their cancer journey, and to contribute to further demand for oncology drugs [12]. The UK National Health Service recently signalled the need for improved evidence of value, and the need to contain costs, by announcing that over a dozen new cancer medicines will no longer be funded through the Cancer Drugs Fund [13].

Many countries use health technology assessments (HTAs) to make resource allocation decisions, which consider safety, clinical efficacy, effectiveness, cost and cost effectiveness, organizational implications, social consequences, and the legal and ethical aspects of adopting new health technologies. Thus, it could be argued that HTA decision processes already assign weights to a range of social values [14]. For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK assesses the cost effectiveness of new medicines—relative to a threshold value or opportunity cost—and, therefore, appears to be using a social decision rule that includes (1) public values of ‘efficiency’ (to produce the most health for those patients that a society is willing to pay for), (2) distribution of funding resources based on ‘need’ (capacity to benefit), and (3) non-discrimination [15]. In particular, payers who use preference-based measures of health outcomes (such as quality-adjusted life-years; QALYs) in drug funding evaluations have, to some extent, included both patient and public perspectives. In this way, democratic governments aim to make decisions aligned with social values, as expressed through a political process.

In response to public demand for access to expensive, and sometimes cost-ineffective drugs, some governments have sought patient/public input to refine understanding of their societies’ values. Several countries have taken overt steps to engage their citizens in priority setting, to strengthen accountability, healthcare outcomes and public relations [16–18]. Yet, public demand for financial support of unfunded cancer medicines persists, suggesting that there remains a gap between the value of new cancer drugs as perceived by decision makers as compared to citizens [19–21].

Many in the HTA community consider it important to include citizen priorities, because patients, their caregivers and the general public are often the most directly affected by public funding decisions [16–18]. Yet, consensus is lacking on how to integrate citizen preferences into public funding decisions, raising questions about how patient and public input is currently being utilized [22]. Even where citizen involvement in priority setting is mandatory, scant information is available regarding the public and patient input submitted. This makes it difficult to identify citizen funding priorities, and, thus, difficult to determine (1) whether citizen preferences differ significantly from those of decision makers, (2) how citizen input is applied in funding decisions, and (3) the true impact of citizen involvement. These issues are perhaps most critical in cancer and other serious illnesses that involve judgements about the value of incremental gains for patients whose condition may be terminal.

The aim of this review was to identify and compare the preferences of patients, the general public and payers, to determine the values that should shape public funding decisions for new cancer therapies, and to assess whether citizen priorities differ significantly from, and conflict with, existing public funding priorities. We based our analysis on studies that used (1) measures of preference (e.g. conjoint analysis) and (2) measures of value (e.g. willingness to pay). We focussed on cancer drugs (as a proxy for serious illness) and the criteria used in payer funding decisions (e.g. evidence of efficacy), rather than the process (e.g. fairness and legitimacy of decisions). To our knowledge, this is the first critical review to identify and compare the funding preferences of patients, the general public and drug funding decision makers.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature Search for Empirical Preference Studies

We conducted a comprehensive search of the published literature to identify the evidence base regarding the funding priorities (stated and revealed preferences) of patients, the general public and funding decision makers (‘payers’), within the context of priority setting for cancer medicines. Peer-reviewed, empirical, English-language publications were identified using a structured strategy, which was applied to several bibliographic databases. The search strategy combined specific MeSH terms (e.g. neoplasm, resource allocation) and specific keywords identified from an analysis of known key references. Search terms comprised five key concepts: cancer (e.g. carcinoma, neoplasm), drug (e.g. chemotherapy, high-cost medicine), funding (coverage, priority setting), preference method (discrete choice, interview) and stakeholder (patient, public, payer). Search strategy details are described in Online Resource 1: ‘Detailed Search Strategy for Empirical Studies of Cancer Drug Funding Decision Criteria’.

2.2 Identification of Potential Studies for Inclusion

The search was applied to all available dates in PubMed (NCBI), EMBASE (via OvidSP), Web of Science, Business Source Complete, MEDLINE (OvidSP) and EconLit. We did not include ‘grey literature’ as it was unlikely to yield study designs that met inclusion criteria. The electronic search was supplemented by a manual search of the references of papers meeting inclusion criteria.

2.3 Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if (1) the study was published in English in a peer-reviewed source, (2) the funding criteria pertained to a cancer drug for a group of patients, (3) study subjects were cancer patients, the general public or payers, (4) the study design included quantitative (e.g. discrete choice, conjoint analysis) or qualitative (focus groups, case study) measures of preference, and (v) study outcomes include measures of value, relevant to cancer (e.g. willingness to pay) [23–25]. We excluded studies concerning individuals willing to fund their own cancer drugs, as our objective was to identify stakeholders’ preferences for the funding of cancer drugs. The literature search was conducted 7 January 2015 and updated to include all identified studies published in peer-reviewed journals up to 30 March 2015.

2.4 Identification of Qualifying Studies and Quality Assessment

The titles and abstracts of retrieved records were screened against inclusion criteria by one reviewer (TM). Full-text articles of studies potentially meeting inclusion criteria were retrieved by one reviewer (TM), and determination of final studies for inclusion was reached by discussion and consensus by two reviewers (TM, AH). We needed a tool for evaluating the methodological quality of empirical research papers across a range of methods, and chose the HTA-based quality assessment tool designed by Kmet et al., which is based on a systematic literature review, and includes two quality assessment checklists, one for quantitative studies and one for qualitative studies [26]. The quality of included studies was then evaluated by one reviewer (TM) using a conservative 70 % cut-point for exclusion. Quantitative and qualitative studies were rated respectively against 14 or ten criteria, using a 3-point scale (yes = 2, partial = 1; no = 0) to assess study design, context, sampling strategy, data collection methods, data analysis, blinding, biases, etc., by one reviewer (TM) [26]. Studies using both quantitative and qualitative methods were evaluated for quality against both sets of criteria. All studies meeting 70 % of the 14 quantitative or ten qualitative criteria were included. See Online Resource 2: ‘Quality Assessments of Studies Meeting Inclusion Criteria’.

2.5 Data Extraction

We extracted verbatim all terms and phrases conveying the funding preferences of patients, the general public and payers into a table, and also extracted information regarding the country, stakeholder perspective, study citation, methods, objective, sample characteristics, funding criteria and conclusions (one reviewer, TM).

2.6 Data Synthesis

A framework was needed for comparing patient, public and payer funding preferences. We identified six published reviews of the criteria applied by payers used in pharmaceutical funding decisions [27–32], and chose Guindo et al. as the most comprehensive and relevant organizing framework for our purpose [32]. This framework examined payer decision making at ‘micro’ (healthcare provider), ‘meso’ (healthcare facility) and ‘macro’ (national/regional healthcare decision-making) levels, and identified and categorized funding criteria based on 40 studies of public healthcare resource allocation, from several world regions. The framework includes 338 terms, organized into 58 criteria and grouped into nine categories (‘health outcomes’; ‘benefit types’; ‘disease impact’; ‘therapeutic context’; ‘economic impact’; ‘evidence quality’; ‘implementation complexity’; ‘priority, fairness and ethics’; ‘overall context’). Our focus was to compare the funding preferences of payers, the public and patients at the ‘macro’ level. Therefore, while some criteria were not relevant (e.g. ‘research ethics’, as in physicians involved in clinical trials; ‘skills’ as hospital staff training), new criteria could easily be incorporated. For simplicity, we maintained Guindo et al.’s alphanumeric classification system, to facilitate comparison of our findings to those of Guindo et al., which assess funding preferences for ‘medicines in general’. Online Resource 3 provides background regarding Guindo et al.’s classification system of healthcare funding criteria.

Our goals were to identify the criteria considered by each stakeholder and to identify similarities and differences between the criteria considered by patients, the public and payers. Using Guindo et al.’s coding system (A1, A2…) and funding criteria terms as a guide, we identified and extracted funding criteria verbatim into a table, organized in alignment with Guindo et al.’s nine categories and associated criteria. From each included study, we allocated 1 point for each identified criterion (‘frequency counts’, a method commonly used when analysing quantitative and qualitative together) [33, 34]. ‘New’ criteria not previously identified by Guindo et al. were incorporated using the same process. We then calculated the relative frequency of each criterion by stakeholder. For example, the preference for funding cancer drugs that are potentially life-saving—coded in Guindo et al.’s criteria as ‘A3 Life-saving’—was identified in three patient studies, and, thus, comprised 9 % (3/32) of patient funding preferences. In comparison, the funding preferences for ‘A3 Life-saving’ treatment were 6 % (4/62) of public funding preferences and 5 % (7/148) of payer funding preferences across stakeholders. We then compared similarities and differences in funding preferences between patients, public and payers, and considered the potential implications of our findings regarding the inclusion of patient and general public funding priorities into public drug funding decisions for cancer drugs, and for high-cost medicines in general. Quantitative and qualitative characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics.

3 Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

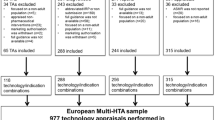

The search strategy yielded 13,039 unique studies, of which 185 met our inclusion criteria. Initial title and abstract screening reduced our sample to 31 studies; full-text review left 23 studies. Screening of secondary references from eligible studies yielded two additional studies, for a total of 25 studies. A flow diagram of the literature search is shown in Fig. 1. Details of included studies are provided in Table 1.

The final sample comprised 25 studies, of which 23 evaluated funding preferences from a single perspective (patient, public or payer; 23 perspectives) and two studies evaluated funding preferences from dual perspectives (patient + public; four perspectives). This yielded a total of 27 funding perspectives: 11/27 from the payer perspective (41 %) [35–45], 9/27 from the public perspective (33 %) [46–54], and 7/27 from the patient perspective (26 %) [53–59]. Sample studies used surveys, regression analysis and/or document analysis to collect and evaluate data. Methods were mainly quantitative in patient (80 %) and public (89 %) studies; mixed methods were more common in payer studies (26 % quantitative, 74 % qualitative).

Of the 16 countries or jurisdictions represented, funding perspectives were evaluated for patients (three countries), the general public (seven countries) and payers (14 countries) (Fig. 2). The majority (69 %) of the preferences data came from five countries (England, ten studies [35–37, 42, 43, 51–54, 59]; USA, six studies [36, 42, 50, 56–58]; Canada, five studies [36, 38, 39, 43, 45]; Australia, five studies [36, 40, 44, 47, 49]; Scotland, four studies [36, 41, 42, 51]). One large payer study included 13 countries [36]. All studies of patient (6) and general public preferences (6/7) were conducted in single countries, while one-third of payer studies (4/11) compared preferences across two or more countries. All three stakeholder perspectives were evaluated in only two countries (England, USA), but in separate studies. Dual perspectives (‘payer vs. general public’) were evaluated in four countries (Australia, Scotland, Germany, Wales), also in separate studies. The remaining ten countries were evaluated from single perspectives (eight payers, one public and one patient). Table 2 provides verbatim details of stakeholders’ funding preferences, and Fig. 3 graphically depicts these data to show the comparative weighting of funding preferences by stakeholder.

3.2 Funding Priorities of Cancer Patients

Empirical evidence of patient funding preferences for cancer drugs is limited and recent, with six of seven identified studies published from 2010, in three countries (USA, England, South Korea] [53–59]. Overall, we identified 12 patient funding criteria, including four patient-centric criteria that were not in Guindo et al.’s framework and do not appear to be widely considered in public funding decisions: (1) the ‘value of hope’, (2) ‘access to information’ regarding new cancer drug treatment options, (3) ‘public funding for choice of therapy’, and (4) ‘autonomy in treatment decisions’.

Specifically, patients favour funding for cancer medicines that improve health outcomes demonstrated by ‘clinical efficacy’ [55], ‘prolonged survival’ [56–58] and/or ‘quality-of-life benefits’ [55], including ‘relief or prevention of symptoms or complications of disease’, or offer ‘potential survival’, reflecting the ‘value of hope’ for a response to cancer drug treatment [57, 58]. In five of seven studies, patients prioritized funding for cancer drugs providing ‘individual impact and benefit’, and/or offering ‘relief or prevention of symptoms or complications of disease (“quality of life”)’, based on ‘individual need’ [53–58].

Patients also consider the economic impact of cancer medicines and prioritize ‘financial coverage’. In the absence of public funding, cancer patients face significant financial burdens in paying for cancer drugs [55]. Two large US and UK studies, in which patients relied, respectively, on private and public coverage, found that metastatic patients gave very high priority to (public or private) funding for high-cost specialty cancer drugs [57, 58]. These patients considered that cost should not be a consideration in cancer drug funding decisions, once treatment has commenced, as their government has a moral obligation to maintain the ‘continuum of care’, and should not apply rationing by withholding funding for potentially life-saving or life-extending medicines [54, 58]. In a smaller Korean study, breast cancer patients expressed frustration with the lack of public funding for many new breast cancer drugs, which could affect their length of survival and quality of life, and imposed additional financial hardship to patients already heavily burdened with mental, physical and financial challenges (e.g. loss of income) [55]. In these circumstances, patients considered public funding for their cancer medicines as a ‘basic right’, essentially equating ‘right to life’ with ‘right to public funds’ [53]. Thus, continuity of access to cancer drug treatment appears to be an important criterion for cancer patients. This is an important issue in the funding of new cancer medicines, where withdrawal of care even in the absence of effectiveness can be viewed as unethical by patients and potentially by the public.

Finally, many (but not all) patients prioritize ‘access to information’ as a necessary precursor to having ‘autonomy in treatment decisions’. Many patients prefer ‘honesty’, and want access to all relevant information so that they can be involved in decision making about their own treatment. Two recent studies found that patients want to know how financial factors affect their access to cancer medicines, and want the autonomy to decide whether to contest public funding decision making, access care in the private sector, or consider self-funding options [54, 59]. Furthermore, patients expect that their healthcare professionals act as advocates by providing information about potentially beneficial cancer medicines and available routes for contesting funding decisions, and helping them gain access where possible [54, 59]. However, explicitness is not without cost, as some patients expressed the potential for distress if told of a high-cost, non-funded but potentially beneficial new medicine, if they could not secure other funding sources.

3.3 Funding Priorities of the General Public

Public funding preferences were identified in nine studies, from seven countries (England, Australia, Germany, Ireland, Scotland, USA, Wales) [46–54]. Empirical studies of public preferences are also recent and limited, with only one study published before 2006 [53]. We identified 24 funding criteria considered by the general public.

The general public prioritizes funding medicines for severe illnesses, cancer being considered the most severe [46, 50, 51]. Like patients, the public prioritizes funding for cancer treatments that are ‘effective’ and ‘life-saving’, ‘life-extending’ and/or offer ‘improved life quality to individual patients’ [48, 51, 53]. Unlike patients, who are individually focussed, the public also supports funding cancer medicines that offer ‘significant innovation’ (‘effectiveness’) or ‘wider societal benefits’ (e.g. reduced caregiver burden) [47, 48, 51]. The public has a sense of solidarity with cancer patients, and prioritizes investment in innovations for people with cancer, asthma and disabilities over those with drug addiction or obesity [52]. The public also considers the number and type of treatment options available, and prioritized ‘funding for existing treatment alternatives’ (e.g. regulator-approved drug not yet publicly funded) [49, 54]. In one study of public funding preferences in hospital, where cancer treatment costs are typically highest, the majority of those surveyed prioritized funding based on current health status and relative ability to benefit. Nearly 20 % of respondents expressed ‘solidarity’ with cancer patients and favoured funding treatments that offered all patients ‘equal opportunities to live’. However, this appears to be premised on the belief that rationing was unnecessary and that additional funding should be made available [47].

In six of the nine studies, the public prioritizes ‘fairness’ and ‘equity’ in funding cancer drugs [48–51, 53, 54]. In a large UK survey, the public favoured funding cancer medicines based on ‘need’, independent of cost or patients’ ability to benefit [51]. The public also favours funding treatments for those with high risk and increased vulnerability (e.g. high mortality risk), and for patients with prior cancer [48, 53]. The concept of ‘need’ was broadly expressed, including both ‘individual’ need [48, 50, 53] and clinical ‘unmet’ need, for the range of funded drug treatment options [54]. Similar to patients, the public values new cancer drugs when there are no other options, and wants access to information regarding new cancer drugs that can improve survival by 4–6 months [49]. The public also seeks financial risk protection against medical costs due to future illness, and believes their government should fund high-cost cancer drugs [49, 50].

Public preferences vary regarding the role of efficiency in cancer treatment funding decisions. The Irish, English and Australian public surveyed favour efficiency in allocating resources to patients (maximum benefit for the greatest number), to improve overall public sector efficiency [46, 48, 51]. However, those surveyed from the German public believe that, while cost effectiveness should be considered, it should not be a dominant criterion. Differences expressed across countries may reflect different cultural norms, but may also reflect differences in healthcare system finance and experience with priority setting.

Overall, the public prioritizes funding for effective cancer treatments that can benefit individuals and/or society, with equitable access for vulnerable populations with severe illnesses. Comparing patients and the public, the majority of patients’ funding preferences are shared with the general public. However, the public also favours equity and ethical decision making in considering the societal benefits of funding cancer drugs, but has mixed preferences about the extent to which efficiency should be prioritized in funding treatments for serious illnesses.

3.4 Funding Criteria Applied by Payers

Data for payer funding criteria for cancer drugs comes from 11 studies and 14 countries [35–45]. Seven studies examined single countries (England, Canada or Australia) [37–40, 43–45]; four studies examined two or more countries [35, 36, 41, 42]. We identified 35 funding criteria from Guindo et al.’s framework. Overall, payers apply the broadest range of criteria, with the most frequent criteria focussed in four categories: health outcomes, therapeutic context, economic impact and quality of evidence.

In ten of 11 studies, payers funded new cancer drugs on the basis of clinical evidence of ‘health outcomes and benefits’, and collectively considered all five clinical criteria, including safety [36–45]. ‘Economic criteria’ were identified in all 11 payer studies, most regarding evaluating the ‘value for money’ of new cancer drugs [35–45]. Most payer studies also considered ‘evidence quality and uncertainty’ criteria [35–40, 44, 45]. Payers considered the ‘therapeutic context’, based on the need for treatment alternatives, individual and population needs (unmet clinical need), and aspects of equity of access to treatment (e.g. age independent) [37, 38, 40, 43–45]. Payers also considered financial constraints, political aspects, and stakeholder interests and pressure (overall context) [36–40, 45].

The concept of ‘disease severity’ appears to be inter-related with ‘life-threatening’ and ‘life-saving’ as a key funding criterion. Of 11 payer studies, eight considered either ‘life-threat’ and/or ‘life-saving’ as funding criteria: two considered life-threat (but not life-saving) [35, 39], three considered life-threat and life-saving [36, 40, 41]; and three other studies considered life-saving (but not life-threat) as a funding criterion [37, 38, 45]. In one multi-country study, disease severity was considered an ‘overriding variable’ in Sweden, which lacks a defined cost-effectiveness threshold and accepts higher costs for patients with low life quality or expectancy, such as patients with cancer [36]. Of the three remaining studies, two already focussed on cancer as a severe disease and, therefore, did not examine ‘severity’ or ‘life-threat’ [39, 42]; the remaining study examined listing rates of cancer versus non-cancer drugs and did not explicitly examine severity as a funding criterion [44]. Our findings are consistent with the empirical literature of payer funding decisions for pharmaceuticals in general; several countries (Australia, Denmark, France, Norway, the Netherlands, UK) prioritize cancer drug treatments on the basis of disease severity [6, 60, 61], and the related term ‘life-threatening’ is also an identified funding criterion in Australia and Canada [62].

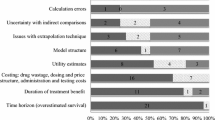

3.5 Comparing Stakeholder Funding Priorities

Our review identified only four new funding criteria, suggesting that Guindo et al.’s framework is reasonably comprehensive for our present inquiry. Overall, payers consider the broadest range of criteria (35), across all categories), the general public considers a moderate number of criteria (24), and patients consider fewer criteria (12). All three stakeholders were aligned on only eight funding criteria—which primarily encompassed the notions of funding effective, life-saving treatments that can provide patient-relevant health benefits to individuals in need. There were also indications that all three stakeholders are concerned with aspects of ‘fairness’ including positive discrimination for vulnerable populations and non-discrimination based on age. These shared criteria reflected just over half of the patient criteria identified. However, patients (and the general public) also consider ‘access to information’, ‘autonomy in decision making’ and the ‘value of hope’, but we found no evidence that payers also share these considerations.

Furthermore, while payers considered most identified patient criteria (9/12) and many of the general public’s criteria (17/24), nearly half (16/35) of criteria prioritized by payers were not shared by both patients and the public, and 27/35 criteria were not explicitly shared by either patients or the public. This was unsurprising, in part, because most criteria unique to payers involve economic evidence, safety, evidence quality and relevance, and the overall context in which a new drug will be funded—topics with less awareness among citizens. The lack of evidence of citizen consideration of these ‘payer criteria’ is perhaps also due to the methods used to elicit citizen preferences (e.g. not being asked about safety attitudes), a lack of awareness (e.g. not being aware of evidence quality issues), or differing perceptions of disease severity (e.g. patients more willing to take risks regarding the safety of cancer treatment) [48, 63]. Thus, the evidence suggests that citizens do not recognize certain factors that payers consider (safety, drug budgets), and conversely, that payers give less weight to certain criteria prioritized by citizens (e.g. payers are less likely to give priority to therapies with poor clinical outcomes even if they provide hope to patients).

4 Discussion

Despite decades of public advocacy for improved access to cancer drugs, our understanding of patient and public preferences regarding cancer drug funding remains incomplete. Only recently has the current health policy literature on drug funding preferences emphasized the need to integrate public and patient preferences into funding decisions. HTA provides a pathway for integrating citizen preferences into healthcare allocation decisions, with the aim of improving the process and outcomes of assessments of a health technology [64, 65]. Citizen input should help to align government and societal preferences, and, thus, improve public funding decisions. Therefore, ‘improved assessments’ would be those which better align citizen and payer funding priorities, based on (1) explicitly recognizing patient and public preferences, (2) integrating these preferences into public healthcare allocation decisions, and (3) allowing for adjustments to the weighting of each stakeholder’s key criteria. However, our study suggests that there are potential areas of conflict: while payers already consider most of the criteria important to citizens, citizens prioritize only some of the criteria important to payers, and also prioritize other criteria not considered by payers.

In general, it appears that payers prioritize a range of healthcare system and ‘efficiency’ factors (‘value for money’, cost effectiveness), while citizens prioritize ‘equity’ factors (economic equality, ‘fairness’), but this may be too simplistic. Differences in perspectives may contribute to different priorities; for example, HTA evaluations of the medical and economic value of new cancer drugs typically centre on median survival gains; however, patients are more likely to consider the range of potential outcomes [58]. In addition, while we would expect patients with a life-threatening condition to prioritize ‘own health’, such patients (and to a lesser extent the public) are less likely to set priorities based primarily on opportunity cost, and instead focus on ‘relative need’—rejecting the reality of scarcity or the resource allocation implications of setting priorities based on broader notions of ‘fairness’. When treatment may save an identified life (‘rule of rescue’), citizens are more likely to empathize and less likely to recognize the opportunity cost of decisions [66, 67].

We identified four patient-centric criteria that have not been directly identified in public funding decisions for cancer drugs: (1) patient financial protection for patient-chosen therapy, (2) access to medical information, (3) levels of autonomy in treatment decision making, and (4) the ‘value of hope’. In general, citizens expect publicly funded financial risk protection for any clinically recommended drug treatment, especially in the event of a personal health crisis [49, 50, 55]. Many patients also want to be informed of new cancer medicines and rationing practices, to facilitate understanding of recommended treatment decisions based on relevant information [54, 57]. Finally, ‘hope’ is an important factor known to impact patient treatment and recovery, and is a highly valued benefit for cancer patients and their families [57, 58]. While rational people understand that some medical conditions are terminal, they may still hope for a chance of the best possible outcome from a current or future therapy [58, 68].

Such patient values are not usually considered in funding decisions, so facilitating the dialogue between citizens and payers provides opportunities to educate and deliberate from both perspectives, to clarify the pivotal issues involved, for a given society. For example, there is a need in each society to consider the question of whether health gains should be weighted differently for different groups of people, such as those with a short life-expectancy. This question has been explored already in some countries. For medicines in general, the public in various European countries want drug funding decisions to be made on the basis of health maximization, equality and urgency, rather than the preferences of the public [69]. In Australia, most people reject priority setting based solely on efficiency (cost effectiveness), and prefer to allocate some funding to high-cost (inefficient) patients so as to provide ‘a chance’ for hope, and to have a ‘fair’ public healthcare system [70, 71]. A recent UK study examining NICE’s supplementary policy for life-extending cancer medicines found, given limited resources, little evidence of public support for end-of-life treatments over other treatment types, with most people favouring treatments based on the size of the potential health gains offered [72].

Perhaps the biggest difference we observed is that some citizens are unwilling to consider opportunity cost, and prioritize need over maximizing population health. Improving alignment of priorities between stakeholders requires explicit recognition of citizen preferences, and potential revision to payers’ criteria weights, to improve assessments of the social value of cancer therapies.

Governments often prioritize equity over efficiency when assisting individuals or subgroups in jeopardy—without guaranteed outcomes—in funding ocean rescues, neonatal ICUs, developmental disability programmes, etc. Citizens with a life-threatening illness would likely consider themselves equally ‘deserving’ of access to publicly funded treatments, regardless of chance for survival or opportunity cost. Some countries have special standards, processes and/or funding for cancer drugs, yet still face public friction when cancer drugs are rejected as cost inefficient [73, 74]. Increasingly, public petitions are used to leverage the political process, to access public funding for specific treatments [75, 76]. These events signal societies’ willingness to pay for cost-inefficient cancer treatments, and suggest that the fundamental conflict has not been resolved.

Understanding what patients and the general public value about new cancer medicines can explain what is driving the growing demand for early access to promising, ‘unproven’ cancer drugs, and perhaps yield insights into what societies might be willing to forego in exchange. This is a necessary first step to reaching payer/citizen consensus regarding the factors that should drive funding priorities for costly treatments for serious illnesses. These key stakeholders will need to discuss shared priorities and enhance improve alignment regarding the criteria to be used and their relative weighting.

Many HTAs in developed countries have created a process for collecting patient and/or public input, yet few collect and share this information publicly. More work is needed to fully engage patient and public participation in the drug evaluation process [77]. Where jurisdictions have not embraced the value of patient and public input, there can be a lack of transparency, making it difficult to identify patient concerns and to determine how patient evidence is being used. Informing the public is a key step in deliberative democracy. If agencies are to solicit patient group submissions, they must clarify how they will use them, and make them public, just as clinical and economic information should be made available. This can improve the legitimacy of funding decisions and reduce the sense of unfairness felt by patients refused publicly funded medicines. Finally, agencies need to clarify how they reconcile their role in representing the preferences of the public with their use of this public and patient data. More research is needed to identify the preferences of patients, the public, payers and policy makers, to understand how cancer medicines, especially at the end of life, are valued by different stakeholders.

It may be that new funding schemes can bridge some of the gap between the demand for cancer medicines and the high opportunity cost of displaced health in the rest of the healthcare system. Performance-based, risk-sharing arrangements are beginning to facilitate restricted funding for new (targeted) therapies that may be effective in some patients even if not on average [78, 79]. Innovative forms of coverage with evidence development might also allow earlier access to new therapies without the threat of discontinuity of treatment. An example might be evidence or outcome based pricing where an initial high price is only maintained if evidence supports it. A more extreme version would be to pay by results, with a high price for an acceptable patient outcome and a low price otherwise.

5 Limitations and Future Research

Empirical studies of cancer drug funding preferences are limited and recent; future studies should consider evaluating multiple stakeholder perspectives within and across countries. We included only English-language publications, potentially limiting generalizability of findings. We used criteria and frequency counts as a method of identifying differences between group preferences, which are established methods for analysing quantitative and qualitative data, but may have survey biases, are weak tests for differences, and cannot measure differences in preference strengths. Some studies were based on small samples of, therefore, potentially unrepresentative subjects, with questions that were not pre-tested nor based on a clear conceptual basis that allows unbiased questions to be asked of respondents free of framing effects and other potential biases [37–40, 42, 47, 53, 59].

The main limitation of this study is that, even if surveys of stated or revealed preferences do not capture certain funding criteria, it is possible that payers and/or citizens do consider them, overtly or implicitly. For example, some payers do fund cost-ineffective cancer medicines, particularly, in ‘last-line’ cases, perhaps because these treatments offer hope, suggesting that such criteria may be implicit for some decision makers. Increasingly, some payers are funding coverage with evidence development, while others are reluctant to do so perhaps because of the issue of continuity of care.

6 Conclusions

The empirical evidence base for cancer drug funding preferences of citizens and payers is recent and developing. Results of our study suggest that payers consider many factors and prioritize efficiency in funding decisions, while patients and the general public consider fewer factors and prioritize access to cancer treatments with the potential to save or extend life. These differences can explain observed conflicts between citizens and payers regarding public funding allocations for new cancer treatments. Improving alignment between payer and citizen funding priorities might require adjustments to the criteria considered by each, and their relative weighting, to improve the process of decision making and create greater value in healthcare systems.

Some jurisdictions include citizen input in funding decisions, yet information on how patient and public values are being included, and the extent of their impact, is still scarce in some countries. Improved understanding of the factors valued by stakeholders could be realized by making available the volumes of patient and public input collected by payers, in the same way that clinical and economic information is shared. While funding outcomes may or may not change, in a democratic process, those affected by public funding decisions should have the right to understand how and why funding decisions are made.

References

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Sorenson C, Drummond M, Kanavos P. Ensuring value for money in healthcare: the role of health technology assessment in the European Union. European observatory on health systems and policies. Observatory studies series No. 11. Copenhagen: WHO; 2008. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/98291/E91271.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2015.

Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information; exploring patients’ preferences. JAMA. 2014;302:195–7.

Institute of Medicine, Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

Chalkidou K, Lopert R, Gerber A. Paying for “end-of’life” drugs in Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom: balancing policy, pragmatism, and societal values. Commonw Fund. 2012;1576:2.

Sabik LM, Lie RK. Priority setting in health care: lessons from the experiences of eight countries. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7:4.

Wilson A, Cohen J. Patient access to new cancer drugs in the United States and Australia. Value Health. 2011;14:944–52.

Busse R, Orvain J, Drummond M, Felix G, Malone J, Alric R, et al. Best practices in undertaking and reporting health technology assessments; Working Group 4 Report. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;2:361–422.

Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790–801.

Ahmad AS, Ormiston-Smith N, Sasieni PD. Trends in the lifetime risk of developing cancer in Great Britain: comparison of risk for those born from 1930 to 1960. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:943-7.

Rickwood S, Kleinrock M, Nunez-Gaviria M, Sakhrani S, Aitken M. The global use of medicines: outlook through 2017. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. 2013. http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Reports/Global_Use_of_Meds_Outlook_2017/IIHI_Global_Use_of_Meds_Report_2013.pdf. Accessed 2 Feb 2015.

Aitken M, Altmann T, Rosen D. Engaging patients through social media: is healthcare ready for empowered and digitally demanding patients? IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics; 2014. pp. 1–47. http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Reports/Secure/IIHI_Social_Media_Report_2014.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2015.

Editorial. Change ahead for cancer drug funding. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e47.

Baker R, Bateman I, Donaldson C, Jones-Lee M, Lancsar E, Loomes G, et al. Weighting and valuing quality-adjusted life-years using stated preference methods: preliminary results from the Social Value of a QALY Project. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–162.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social value judgements: principles for the development of NICE Guidance, 2nd edn. London: NICE; 2008. www.nice.org.uk. Accessed 20 Feb 2015.

O’Quinn S. Patient involvement in drug coverage review. Ontario Public Drug Programs: Patient Evidence Submissions. Toronto: Ontario Public Drug Programs, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2011. https://www.cadth.ca/media/events/june-22-11/Ontario_Public_Drug_Program.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2015.

Loh A, Simon D, Bieber C, Eich W, Härter M. Patient and citizen participation in German health care—current state and future perspectives. Z für ärztliche Fortbild und Qual im Gesundheitswes. 2007;101:229–35.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Patient and public involvement policy. London: NICE; 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/nice-communities/public-involvement/patient-and-public-involvement-policy.

Bastian H. Speaking up for ourselves: the evolution of consumer advocacy in health care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1998;1:3–23.

Campbell D. Patients denied key treatments due to NHS cost-cutting, surgeons warn. The Guardian. 2011. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2011/apr/18/nhs-cost-cutting-surgeon-warning. Accessed 31 Jan 2015.

Kaye KI, Lu CY, Day RO. Can we deny patients expensive drugs? Aust Prescr. 2006;29:146–8.

Facey KM, Hansen HP. Patient-focused HTAs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:273–4.

Ryan M, Scott D, Reeves C, Bate A, van Teijlingen E, Russell EM, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2001;5:1–186.

Ramsey S, Schickedanz A. How should we define value in cancer care? Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 1):1–4.

Lehoux P, Williams-Jones B. Mapping the integration of social and ethical issues in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;1:9–16.

Kmet L, Lee R, Cook L. HTA initiative #13: standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR); 2004. pp. 1–22. http://www.ihe.ca/documents/HTA-FR14.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Baltussen R, Niessen L. Priority setting of health interventions: the need for multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2006;4:14.

Hasman A, McIntosh E, Hope T. What reasons do those with practical experience use in deciding on priorities for healthcare resources? A qualitative study. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:658–63.

Vuorenkoski L, Toiviainen H, Hemminki E. Decision-making in priority setting for medicines—a review of empirical studies. Health Policy. 2008;86:1–9.

Golan O, Hansen P, Kaplan G, Tal O. Health technology prioritization: which criteria for prioritizing new technologies and what are their relative weights? Health Policy. 2011;102:126–35.

Tromp N, Baltussen R. Mapping of multiple criteria for priority setting of health interventions: an aid for decision makers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:454.

Guindo LA, Wagner M, Baltussen R, Rindress D, van Til J, Kind P, et al. From efficacy to equity: literature review of decision criteria for resource allocation and healthcare decisionmaking. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2012;10:9.

Prasad B, Teoksessa D, Bhaskaran V. Content analysis: a method in social science research. In: Lal Das D, editor. Research methods for social work. New Delhi: Rawat Publications; 2008. p. 174–93.

Berelson BR. Content analysis in communication research. New york: Hafner; 1971.

Mason AR, Drummond MF. Public funding of new cancer drugs: is NICE getting nastier? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1188–92.

Cheema PK, Gavura S, Migus M, Godman B, Yeung L, Trudeau ME. International variability in the reimbursement of cancer drugs by publically funded drug programs. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:165–76.

Foy R, So J, Rous E, Scarffe JH. Perspectives of commissioners and cancer specialists in prioritising new cancer drugs: impact of the evidence threshold. BMJ. 1999;318:456–9.

Martin DK, Pater JL, Singer PA. Priority-setting decisions for new cancer drugs: a qualitative case study. Lancet. 2001;358:1676–81.

Rocchi A, Menon D, Verma S, Miller E. The role of economic evidence in Canadian oncology reimbursement decision-making: to lambda and beyond. International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR). Value Health. 2008;11:771–83.

Gallego G, Taylor SJ. Brien J-AE. Funding and access to high cost medicines in public hospitals in Australia: decision-makers’ perspectives. Health Policy. 2009;92:27–34.

Vegter S, Rozenbaum MH, Postema R, Tolley K, Postma MJ. Review of regulatory recommendations for orphan drug submissions in the Netherlands and Scotland: focus on the underlying pharmacoeconomic evaluations. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1651–61.

Mason A, Drummond M, Ramsey S, Campbell J, Raisch D. Comparison of anticancer drug coverage decisions in the United States and United Kingdom: does the evidence support the rhetoric? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3234–8.

Menon D, Stafinski T, Stuart G, Access S, Menon D, Stafinski T, et al. Access to drugs for cancer: does where you live matter? Can J Public Health Rev Can. 2005;96:454–8.

Chim L, Kelly PJJ, Salkeld G, Stockler MRR. Are cancer drugs less likely to be recommended for listing by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in Australia? Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:463–75.

Singer P, Martin D, Giacomini M, Purdy L. Priority setting for new technologies in medicine: qualitative case study. BMJ. 2000;321:1316–8.

Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Preferences of the public regarding cutbacks in expenditure for patient care: are there indications of discrimination against those with mental disorders? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:369–77.

Gallego G, Taylor SJJ, McNeill P, Brien JEE. Public views on priority setting for high cost medications in public hospitals in Australia. Heal. Expect. 2007;10:224–35.

O’Shea E, Gannon B, Kennelly B. Eliciting preferences for resource allocation in mental health care in Ireland. Health Policy. 2008;88:359–70.

Mileshkin L, Schofield PE, Jefford M, Agalianos E, Levine M, Herschtal A, et al. To tell or not to tell: the community wants to know about expensive anticancer drugs as a potential treatment option. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5830–7.

Romley JA, Sanchez Y, Penrod JR, Goldman DP. Survey results show that adults are willing to pay higher insurance premiums for generous coverage of specialty drugs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:683–90.

Linley WGG, Hughes DAA. Societal views on NICE, Cancer Drugs Fund and Value-Based Pricing criteria for prioritizing medicines: a cross-sectional survey of 4118 adults in Great Britain. Health Econ. 2012;22:948–64.

Erdem S, Thompson C. Prioritising health service innovation investments using public preferences: a discrete choice experiment. 2014;14:1–14.

Burgoyne CB. Distributive justice and rationing in the NHS: framing effects in press coverage of a controversial decision. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 1997;7:119–36.

Jenkins VA, Trapala I, Parlour L, Langridge C, Fallowfield L. The views of patients and the general public about expensive anti-cancer drugs in the NHS: a questionnaire-based study. J R Soc Med Sh Rep. 2011;2:69.

Oh D-Y, Crawford B, Kim S-B, Chung H-C, McDonald J, Lee SY, et al. Evaluation of the willingness-to-pay for cancer treatment in Korean metastatic breast cancer patients: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8:282–91.

Goldman DP, Jena AB, Lakdawalla DN, Malin JL, Malkin JD, Sun E. The value of specialty oncology drugs. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:115–32.

Seabury SA, Goldman DP, Maclean JR, Penrod JR, Lakdawalla DN. Patients value metastatic cancer therapy more highly than is typically shown through traditional estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:691–9.

Lakdawalla DN, Romley JA, Sanchez Y, Maclean JR, Penrod JR, Philipson T. How cancer patients value hope and the implications for cost-effectiveness assessments of high-cost cancer therapies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:676–82.

Owen-Smith A, Coast J, Donovan J. Are patients receiving enough information about healthcare rationing? A qualitative study. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:88–92.

Harris AH, Hill SR, Chin G, Li JJ, Walkom E. The role of value for money in public insurance coverage decisions for drugs in Australia: a retrospective analysis 1994–2004. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:713–22.

Le Pen C, Priol G, Lilliu H. What criteria for pharmaceuticals reimbursement? An empirical analysis of the evaluation of “medical service rendered” by reimbursable drugs in France. Eur J Health Econ HEPAC Heal Econ Prev care. 2003;4:30–6.

Clement FM, Harris A, Yong K, Lee KM, Manns BJ. Using effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to make drug coverage decisions: a comparison of Britain, Australia and Canada. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:1437.

Weinstein ND. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science. 1989;246:1232–5.

Farrell C. Patient and public involvement: the evidence for policy implementation. London: Department of Health; 2004.

Facey K, Boivin A, Gracia J, Hansen HP, Lo Scalzo A, Mossman J, et al. Patients’ perspectives in health technology assessment: a route to robust evidence and fair deliberation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2010;26:334–40.

McKie J, Richardson J. The rule of rescue. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2407–19.

Cookson R, Dolan P, Anglia E. Principles of justice in health care. 2000;26:323–9.

Becker G, Murphy K, Philipson T. The value of life near its end and terminal care. Cambridge, Mass. Report No: Working Paper 13333; 2007.

Richardson J, McKie J, Olsen J. Welfarism or non-welfarism? Public preferences for willingness to pay versus health maximization. Monash University, Centre for Health Economics Research Paper 2005 (10); 2005. http://arrow.monash.edu.au/hdl/1959.1/42366. Accessed 13 Dec 2014.

McKie J, Shrimpton B, Richardson J, Hurworth R. Treatment costs and priority setting in health care: a qualitative study. Aust N Z Health Policy. 2009;6:11.

Richardson J, McKie J, Peacock S, Iezzi A. Severity as an independent determinant of the social value of a health service. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12:163–74.

Shah KK, Tsuchiya A, Wailoo AJ, Hole AR, Health A, Thea T, et al. Valuing health at the end of life: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. HEDS Discuss Pap. 2012;124:1–56.

Crooks D, Savage C. Pan-Canadian oncology drug review: update on progress. Cancer Advocacy Coalition Canada. 2013. http://www.canceradvocacy.ca/reportcard/2013/Pan-Canadian%20Oncology%20Drug%20Review.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2014.

Donnelly L. Cancer patients facing race against clock for drugs in fund “betrayal.” The Telegraph. 2013. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/9972714/Cancer-patients-facing-race-against-clock-for-drugs-in-fund-betrayal.html. Accessed 20 Dec 2014.

Walker J. Scottish cancer drug fund. SPICe. 2013;12:1–4.

Musgrave T. PBS should pay for abiraterone for all incurable prostate cancer patients. Change.org. https://www.change.org/p/pbs-should-pay-for-abiraterone-for-all-incurable-prostate-cancer-patients. Accessed 20 Dec 2014.

Messina J, Grainger DL. A pilot study to identify areas for further improvements in patient and public involvement in health technology assessments for medicines. Patient. 2012;5:199–211.

Ramsey SD, Sullivan SD. A new model for reimbursing genome-based cancer care. Oncologist. 2014;19:1–4.

Sruamsiri R, Ross-Degnan D, Lu CY, Chaiyakunapruk N, Wagner AK. Policies and programs to facilitate access to targeted cancer therapies in Thailand. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119945.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Duncan Mortimer for assistance with the development of the initial search strategy.

Authorship

This review was undertaken as a component of a doctoral study. TM conducted the literature search, analysed results and drafted the manuscript. TM and AH evaluated studies for inclusion. AH and AM provided edits and knowledgeable guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

No funding was received. TM, AH and AM have no conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacLeod, T.E., Harris, A.H. & Mahal, A. Stated and Revealed Preferences for Funding New High-Cost Cancer Drugs: A Critical Review of the Evidence from Patients, the Public and Payers. Patient 9, 201–222 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0139-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0139-7