Abstract

Introduction

Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) is effective in reducing surgical site infections (SSIs). However, inappropriate use of SAP increases the risk of SSIs and antibiotic resistance.

Objectives

To evaluate the rate of compliance with timing and duration of SAP and to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors associated with SSIs.

Method

This retrospective study was conducted among surgical patients in a tertiary hospital in Malaysia from June to August 2019. Patients’ electronic medical records were reviewed for data collection and the data were analysed using both descriptive and inferential analyses.

Results

This analysis included 127 surgical procedures in patients with a mean age of 43.4 ± 22.3 years and a male preponderance (64%). Only 37.8% received pre-operative SAP, with metronidazole (27.4%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (25.8%) and cefoperazone (22.6%) being the most common antibiotics. Overall, the timing of SAP was inappropriate in 92.1% of the procedures. Approximately 59% received SAP for more than 24 h. Those who received pre-operative antibiotics were less likely to receive SAP beyond 24 h (odds ratio (OR): 0.219; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.082–0.588; p = 0.003). The prevalence of SSI was 16.5% and was associated with the length of hospital stay after surgery (OR: 1.144; 95 CI 1.035–1.265; p = 0.008) and duration of surgery (OR: 1.006; 95% CI 1.000–1.012; p = 0.038), but these significances disappeared in a multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Inappropriate use of SAP was observed including late administration and long duration of antibiotic use. The prevalence of SSIs is high and is associated with duration of surgery and length of hospital stay after surgery. Pre-operative SAP may reduce treatment duration. Antimicrobial stewardship intervention is recommended and infection control strategies should be strengthened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a high rate of inappropriate timing (92.1%) and inappropriate duration (> 50%) of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis among surgical patients. |

Antibiotic stewardship is recommended to improve appropriateness of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and reduce antibiotic resistance. |

Pre-operative surgical antibiotic prophylaxis should be encouraged because it is associated with shorter treatment duration. |

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is one of the most common infections affecting hospitalised patients [1,2,3]. SSIs are associated with significant morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs, and also reduce patients’ quality of life [4,5,6,7]. The prevalence of SSIs varies among countries, with a higher prevalence reported in developing countries (5.6%) compared to developed countries (2.6–2.9%) such as the USA and European countries [8]. In addition, the incidence of SSIs is lower in high-income countries compared to low-income countries [9]. In Malaysia, the incidence of SSIs ranges between 7.7 and 13.8% [10, 11]. SSIs are usually associated with several risk factors including dirty wounds [12, 13], obesity, excessive bleeding, spinal anaesthesia, advanced age, malignancy [14], male gender [13], malnutrition, smoking cigarette, and comorbidities such as cancer and renal failure [15]. It is almost impossible to eliminate the risk of SSIs; however, SSIs can be reduced through surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) [16].

SAP is the administration of intravenous antibiotics within a certain period of time before incision with the goal of preventing infection after surgery. The effectiveness of SAP depends on the choice of antibiotics, timing, and dose and duration of administration. Therefore, inappropriate use of SAP increases the risk of SSI and antimicrobial resistance [14, 17, 18]. Available evidence indicates that there is excessive and inappropriate use of SAP among surgeons [19,20,21,22]. Furthermore, evidence has shown that inappropriate use of SAP increases healthcare costs [23, 24] and the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship reduces the costs of SAP [25]. Antimicrobial stewardship interventions are used to improve compliance with SAP guidelines [25, 26]. However, understanding local compliance with SAP among surgeons is important to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions that will improve compliance with SAP guidelines.

In Malaysia, there is a paucity of data describing the compliance of surgeons with SAP. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the compliance with SAP (timing, dosing, re-dosing and duration) among patients who had a surgical procedure in a tertiary hospital. In addition, the rate of SSIs and the factors associated with SSIs were investigated. The findings will be used to develop antimicrobial stewardship interventions to improve the quality use of SAP and reduce healthcare costs and SSI rates.

Methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective observational study was conducted in a 350-bed capacity teaching hospital located on the Eastern Coast of Malaysia. The hospital provides a wide range of services including surgery, internal medicine, orthopaedic, paediatric, psychiatric, pharmacy, nursing and dentistry. The study was conducted in the hospital’s surgical department, which provides both general and speciality surgical services.

Study population

All hospitalized patients who had surgical procedures at the hospital from 1 June 2019 to 31 August 2019 were included in this study. Patients who had surgeries but had missing or incomplete anaesthesia records were excluded from the study. All surgical wound classes including clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty wounds during the period under review were included.

Data collection

Data were collected using the hospital’s electronic medical records system after obtaining approval from the hospital’s Clinical Research Centre. A list containing the names and hospital registration numbers of all the patients who had a surgical procedure during the period under review was obtained from the hospital’s surgical department. Patients’ hospital registration numbers were used to find the medical records in the electronic record system. The data were collected by a clinical pharmacist and a trained final year pharmacy undergraduate student through the review of patients’ electronic anaesthesia, medical and medications records. The data collected by the final year students were checked for accuracy by the clinical pharmacist. The information collected included: demographics (patient’s age, gender, race, and dates of admission, surgery and discharge) and clinical data (weight, height, comorbidities, type of surgery, nature of surgery, type of anaesthesia, duration of surgery and estimated blood loss). Information related to SAP including antibiotic(s) administered, dose, time of administration, time of incision, additional doses given and the time when they were administered, and the duration were also collected. Information regarding the occurrence of SSIs, type of SSI, date of diagnosis and the pathogen isolated with its antibiotic sensitivities were also documented. All the information was documented on a data collection form.

Outcome measures

The outcomes of the study included: appropriateness of timing of first dose, dose and duration of SAP, and occurrence of SSIs among the patients. Appropriateness of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis was measured using the National Antimicrobial Guidelines published by the Malaysian Ministry of Health in 2019 [27]. The outcome measures are defined as follows:

-

Appropriate timing: A patient received intravenous SAP within 60 min before surgical incision, except fluoroquinolones and vancomycin, which should be administered within 120 min before surgical incision [27].

-

Appropriate dose of SAP: Defined as the dose that is consistent with the recommendations of the National Antimicrobial Guideline including doubling and tripling of the doses in obese patients [27].

-

Appropriate additional dose: Defined as the administration of an additional dose of SAP in patients with either excessive blood loss (> 1500 mL), or if the duration of the procedure exceeds two half-lives of the drug, or any factors that shorten the half-life of antibiotics, for example, extensive burning [27].

-

Appropriate duration of SAP: SAP is discontinued within 24 h (or 48 h in cardiac surgery) after the completion of surgery [27].

Of note, the appropriateness of antibiotics used for surgical prophylaxis was not evaluated in the study because access to information such as history of allergy and availability of first-choice antibiotics at the time was limited due to the retrospective nature of the study. A SSI is defined based on the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention-National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC-NHNS) criteria [28]. SSI is any infection that occurs either at the site of incision or in any other parts of the body within 30 days after surgery in procedures with no implant or within 1 year in implant-related procedures [28]. SSIs documented in the patients’ records during the period defined in the criteria were documented.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 22 Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), using both descriptive and inferential analyses. Categorical and continuous variables were presented as frequencies (with percentages) and mean (with standard deviations), respectively. The association between clinical and demographic variables with SSIs was determined using logistic regression analyses. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 127 surgical procedures were included in the analysis. The mean age and standard deviation of the patients were 43.4 ± 22.3 years and about two-thirds (64%) were males. The median pre-surgical and post-surgical length of hospitalisation was 1 (range 0–12) and 2 (range 0–28) days, respectively. Mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.9 ± 7.4 kg/m2 and 47.2% of the patients were obese, while about 39% had comorbidities including diabetes mellitus (17.2%), hypertension (21.0%), dyslipidaemia (8.3%) and chronic kidney disease (6.4%). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patients.

Characteristics of the surgical procedures

More than 60% of the patients had an elective procedure and 22.8% suffered excessive blood loss during surgery. General anaesthesia (81.1%) was the most commonly used, while general (20.5%), urologic (18.1%) and colorectal (15.7%) surgeries were the most frequent surgeries. The most common surgical procedures were appendectomy (10.2%), hernioplasty (8.7%), incision and drainage (7.1%), percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) (6.3%) and laparotomy (5.5%). Most of the patients (53.6%) had an American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status Classification score of 2. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the surgical procedures.

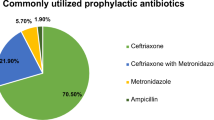

Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis

Overall, 79.5% received antibiotics either before or after surgery. Pre-operative SAP was administered in 37.8% of the procedures, with metronidazole (27.4%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (25.8%) and cefoperazone (22.6%) being the most commonly used antibiotics. Overall, as assessed by the National Antimicrobial Guidelines [20], appropriate timing of SAP was observed in 7.9% of the procedures. Of the 48 procedures that received pre-operative SAP, timing and dose of SAP was appropriate in 16.7% and 87.5%, respectively. The duration of SAP was more than 24 h in 59.1% of the procedures. About two-thirds (62.2%) received antibiotics after the surgery. Both oral and parenteral antibiotics were used after surgery. Cefuroxime (33.3%), metronidazole (33.3%), cefoperazone (24.6%) and ampicillin-sulbactam (14.5%) were the most commonly used intravenous antibiotics. In addition, the most common oral antibiotics used were cefuroxime (52.5%), ampicillin-sulbactam (16.4%) and metronidazole (14.8%). Table 3 describes the oral and parenteral antibiotics used for SAP.

Factors associated with compliance with surgical antibiotic prophylaxis

There was no significant association between compliance with timing of SAP and patients’ demographic, clinical and surgical characteristics. There was a significant association between the use of pre-operative SAP and the duration of SAP. Those who received pre-operative antibiotics were less likely to receive SAP beyond 24 h [odds ratio (OR): 0.219; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.082–0.588; p = 0.003]. Those who received post-operative antibiotics were more likely to have SAP beyond 24 h (OR: 200.7; 95% CI 34.433–1170.406; p < 0.001).

Surgical site infections among the patients

Twenty-one patients (16.5%) had SSIs within 30 days post-surgery. Superficial incisional (61.9%) and organ/space (28.6%) SSIs were the most common. Pathogens isolated included: Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Citrobacter koseri and mixed Gram-negative pathogens. Table 4 describes SSIs among the analysed patients.

Factors associated with surgical site infections (SSIs)

There was no significant association between SSI and patients’ demographic characteristics including age, gender and race. In a univariate logistic regression analysis, the length of hospital stay after surgery (OR: 1.144; 95 CI 1.035–1.265; p = 0.008) and duration of surgery (OR: 1.006; 95% CI 1.000–1.012; p = 0.038) were significantly associated with SSIs. In addition, BMI increased the risk of SSI (OR 1.066; 95% CI 0.995–1.143; p = 0.067) but the association was not statistically significant, while elective surgeries were associated with a non-significant decrease in the risk of SSIs (OR 0.391; 95% CI 0.151–1.015; p = 0.054). Neither length of hospital stay after surgery (adjusted OR: 1.124, 95% CI 0.994–1.271; p = 0.062) nor duration of surgery (adjusted OR: 1.003, 95% CI 0.995–1.010, p = 0.490) showed a significant association with SSIs in the multivariate regression analysis.

Discussion

The current study found that there is an inappropriate use of SAP and this is similar to findings of previous studies [19, 21, 22, 29]. About two-thirds of the procedures (62.2%) were performed without pre-operative SAP, and this is in contrast with the results of a study conducted in Pakistan [29]. Pre-operative SAP minimizes the risk of SSIs as described in a previous study [30], and this is not consistent with the current study due to the small sample. Overall, only 7.9% received SAP at the appropriate time, and this is consistent with a previous study conducted in Malaysia [10], but lower than the findings of studies conducted in other developing countries (16.5–94.6%) [19, 31,32,33]. Inappropriate timing of SAP is associated with SSIs because adequate concentrations of antibiotics in the tissue and blood from the time of incision till the end of the procedure is important to prevent SSIs [17]. In addition, early administration of SAP is an independent risk factor for SSIs [14]. Low rate of compliance with timing of SAP could be attributed to the lack of an institutional protocol for SAP [19] and lack of knowledge regarding the appropriate time to administer SAP and its impact on SSIs [34,35,36].

In the current study, about 60% of the patients received SAP for more than 24 h. This is lower than the results reported in previous studies [10, 19, 20] but similar to the finding of an Iranian study [33]. A previous review revealed that compliance with duration of SAP is less than 50% in most studies [22]. Excessive use of SAP is attributed to the lack of consensus among surgeons regarding guideline recommendations and the misconception that prolonged use of SAP will reduce the risk of SSIs [22]. In the current study, it was found that pre-operative SAP was significantly associated with compliance duration of SAP. Those who received SAP after surgery were more likely to have a duration of SAP beyond 24 h, although the CI is high, probably due to the small sample in this study. This highlights the importance of improving compliance with timing in order to increase compliance with duration of SAP. The prolonged use of SAP is associated with a greater risk of adverse effects including Clostridium difficile infection [37] and increased cost of SAP [30].

The current study revealed that beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations, metronidazole and third-generation cephalosporins were the most common antibiotics used for pre-operative SAP. However, cefuroxime and metronidazole were the most commonly used antibiotics administered after surgery. Cefazolin and cefuroxime are the most common antibiotics recommended for SAP based on the guidelines [27]. This indicates the excessive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in the pre-operative stage and highlights the need for antimicrobial stewardship interventions to reduce the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. A previous study demonstrated the impact of a pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship intervention in reducing the excessive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics [25]. There is an opportunity for hospital pharmacists to improve compliance with SAP guidelines in the hospital setting. However, lack of knowledge and lack of support from hospital administrators are major barriers mitigating against pharmacists’ involvement in antimicrobial stewardship [38]. Therefore, training of practicing pharmacists and future pharmacists is recommended to improve the rational use of antibiotics in surgical patients [38,39,40].

SSIs were reported in 16.5% of the procedures, and this is higher than the findings in previous studies conducted in Malaysia [10, 11]. This could be attributed to the low rate of compliance with SAP, although compliance with infection control strategies may also play a role in the occurrence of SSIs. In the current study, the risk of SSIs is significantly associated with the duration of surgery, and this is consistent with the results of previous studies conducted in Malaysia [12, 15]. Long duration of surgery increases the risk of pathogen contamination at the incision site [41], possibly due to glove perforation in extended surgical procedures [42]. In addition, the concentration of antibiotics administered before incision will diminish in surgeries with extended durations. Therefore, strategies to improve intraoperative SAP in extended procedures are recommended. It is important to note that the significant association between the duration of hospital stay after surgery and the duration of surgery with the occurrence of SSIs in the univariate regression analysis disappeared in the multivariate analysis. This could be attributed to the small sample size included in the current study. Therefore, additional studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to validate these findings.

The study has some limitations, and should be interpreted with caution. Firstly, the study was conducted in one hospital and this will affect its external validity. Secondly, the sample size was small and the period of study was short. Thirdly, the study is retrospective in nature and there are missing data, which may affect the outcome of the study. Fourthly, the appropriateness of indication and the appropriateness of antibiotic choice were not evaluated in the current study. Lastly, the diagnosis of SSI is based on the information on patients’ electronic records. There is a possibility that some patients had SSIs but did not return to the hospital. Therefore, the prevalence of SSIs may be underestimated. Despite these limitations, the current study described compliance with SAP and the prevalence of SSIs and its associated risk factors in a Malaysian hospital.

Conclusion

There is a low rate of compliance with the timing of SAP and prolonged use of antibiotics among patients who undergo surgery. The rate of SSIs is high and is associated with the duration of hospital stay after surgery and the duration of surgery in univariate regression analysis. These findings highlight the importance of an antibiotic stewardship programme to improve the quality use of SAP and reduce the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance.

References

Abubakar U. Point-prevalence survey of hospital acquired infections in three acute care hospitals in Northern Nigeria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00722-9.

Chen Y, Zhao JY, Shan X, et al. A point-prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infection in fifty-two Chinese hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(1):105–11.

Cai Y, Venkatachalam I, Tee NW, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use among adult inpatients in Singapore acute-care hospitals: results from the first national point prevalence survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(Suppl 2):S61–7.

Badia JM, Casey AL, Petrosillo N, et al. Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review in six European countries. J Hosp Infect. 2017;96(1):1–5.

Totty JP, Moss JW, Barker E, et al. The impact of surgical site infection on hospitalisation, treatment costs, and health-related quality of life after vascular surgery. Int Wound J. 2021;18(3):261–8.

Avsar P, Patton D, Ousey K, et al. The impact of surgical site infection on health-related quality of life: a systematic review. Wound Manag Prev. 2021;67(6):10–9.

Strobel RM, Leonhardt M, Förster F, et al. The impact of surgical site infection—a cost analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;14:1.

Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):228–41.

Danwang C, Bigna JJ, Tochie JN, et al. Global incidence of surgical site infection after appendectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2): e034266.

Oh AL, Goh LM, Azim NA, et al. Antibiotic usage in surgical prophylaxis: a prospective surveillance of surgical wards at a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(02):193–201.

Buang SS, Haspani MS. Risk factors for neurosurgical site infections after a neurosurgical procedure: a prospective observational study at Hospital Kuala Lumpur. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67(4):393–8.

Tan LT, Shiang F, Wong J, et al. A prospective study of surgical site infection in elective and emergency general surgery in a tertiary public hospital in Malaysia—a preliminary report. Madridge J Surg. 2019;2(1):52–8.

Wong KA, Holloway S. An observational study of the surgical site infection rate in a General Surgery Department at a General Hospital in Malaysia. Wounds Asia. 2019;2(2):10–9.

Fadzwani B, Raha AR, Nadia MN et al. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis: incidence and risk of surgical site infection. Int Med J Malaysia. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31436/imjm.v19i1.1331

Leong WJ, Hasan H, Zakaria Z, et al. Risk factors and etiologies of clean and clean contaminated surgical site infections at a tertiary care center in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2017;48(6):1299–307.

Najjar PA, Smink DS. Prophylactic antibiotics and prevention of surgical site infections. Surg Clin. 2015;95(2):269–83.

De Jonge SW, Gans SL, Atema JJ, et al. Timing of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in 54,552 patients and the risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006903.

Harbarth S, Samore MH, Lichtenberg D, et al. Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis after cardiovascular surgery and its effect on surgical site infections and antimicrobial resistance. Circulation. 2000;101(25):2916–21.

Abubakar U, Sulaiman SS, Adesiyun AG. Utilization of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for obstetrics and gynaecology surgeries in Northern Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(5):1037–43.

Abubakar U. Antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in northern Nigeria: a multicenter point-prevalence survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-4815-4.

Khan Z, Ahmed N, Zafar S, et al. Audit of antibiotic prophylaxis and adherence of surgeons to standard guidelines in common abdominal surgical procedures. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(9):1052–61.

Ng RS, Chong CP. Surgeons’ adherence to guidelines for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis–a review. Australas Med J. 2012;5(10):534. https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2012.1312.

Yalcin AN, Erbay RH, Serin S, et al. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis and cost in a Turkish University Hospital. Infez Med. 2007;15(2):99–104.

Hatam N, Askarian M, Moravveji AR, et al. Economic burden of inappropriate antibiotic use for prophylactic purpose in Shiraz, Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(4):234.

Abubakar U, Syed Sulaiman SA, Adesiyun AG. Impact of pharmacist-led antibiotic stewardship interventions on compliance with surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in obstetric and gynecologic surgeries in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3): e0213395.

Brink AJ, Messina AP, Feldman C, et al. From guidelines to practice: a pharmacist-driven prospective audit and feedback improvement model for peri-operative antibiotic prophylaxis in 34 South African hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(4):1227–34.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. National antimicrobial guideline 2019. Ministry of Health Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. 2019. https://www.pharmacy.gov.my/v2/en/documents/national-antimicrobial-guideline-nag-2019-3rd-edition.html. Acessed 4 Apr 2022.

Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(5):309–32.

Khan Z, Ahmed N, Rehman AU, et al. Audit of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis usage in elective surgical procedures in two teaching hospitals, Islamabad, Pakistan: an observational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4): e0231188.

Viamonte KR, Tames AS, Correa RS, et al. Compliance with antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines in caesarean delivery: a retrospective, drug utilization study (indication-prescription type) at an Ecuadorian hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00843-1.

Alshehhi HS, Ali AA, Jawhar DS, et al. Assessment of implementation of antibiotic stewardship program in surgical prophylaxis at a secondary care hospital in Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1.

Tietel M, Shema-Didi L, Roth R, et al. Compliance with a new quality standard regarding administration of prophylactic antibiotics before cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021:1–7.

Mousavi S, Zamani E, Bahrami F. An audit of perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis: compliance with the international guidelines. J Res Pharm Pract. 2017;6(2):126.

Abubakar U, Sulaiman SA, Adesiyun AG. Knowledge and perception regarding surgical antibiotic prophylaxis among physicians in the department of obstetrics and gynecology. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;37(1):108–13.

Ahmed AM, Nasr S, Ahmed AM, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of surgical staff towards preoperative surgical antibiotic prophylaxis at an academic tertiary hospital in Sudan. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13(1):1–6.

Pelullo CP, Pepe A, Napolitano F, et al. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis: knowledge and attitudes among resident physicians in Italy. Antibiotics. 2020;9(6):357.

Poeran J, Mazumdar M, Rasul R, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis and risk of Clostridium difficile infection after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(2):589–97.

Lai WM, Islahudin FH, Ambaras Khan R, et al. Pharmacists’ perspectives of their roles in antimicrobial stewardship: a qualitative study among hospital pharmacists in Malaysia. Antibiotics. 2022;11(2):219.

Teoh CY, Mhd. Ali A, Mohamed Shah N, et al. Self-perceived competence and training needs analysis on antimicrobial stewardship among government ward pharmacists in Malaysia. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2020;2(3):035.

Abubakar U, Muhammad HT, Sulaiman SA, et al. Knowledge and self-confidence of antibiotic resistance, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and antibiotic stewardship among pharmacy undergraduate students in three Asian countries. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2020;12(3):265–73.

Cheng H, Chen BP, Soleas IM, et al. Prolonged operative duration increases risk of surgical site infections: a systematic review. Surg Infect. 2017;18(6):722–35.

Makama JG, Okeme IM, Makama EJ, et al. Glove perforation rate in surgery: a randomized, controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of double gloving. Surg Infect. 2016;17(4):436–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the Heads of Surgery, Pharmacy and Records Departments for the assistance they provided during data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the IIUM Research Ethics Committee, reference number: IIUM/504/14/11/2/IREC 2020-104.

Consent to participate

The Human Research Ethics Committee granted a waiver for patient informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable

Author contributions

AU and NFZ designed the study and collected the data, analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SCA contributed in data collection and SCA and FUK reviewed the manuscript draft. All the authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zammari, N.F., Abubakar, U., Che Alhadi, S. et al. Use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and the prevalence and risk factors associated with surgical site infection in a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Drugs Ther Perspect 38, 235–242 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-022-00914-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-022-00914-w