Abstract

Background

The off-label use of medicines is a common practice that occurs over a wide range of therapeutic areas in both adults and children, but occurs much more frequently in pediatric population. So far, the extent of off-label use among children in Bulgaria has not been studied.

Objective

The aim of this nested, retrospective, non-interventional, single-center study is to provide data on the frequency, type, and the most common situations in which off-label medicines are prescribed in daily pediatric practice in Bulgaria.

Methods

The data on prescriptions of 360 pediatric outpatients, treated during a 1-year period, were recorded and provided for analysis. The summaries of product characteristics (SmPC) were used as reference documents for the assessment of prescriptions. Descriptive statistics, with absolute frequencies, means, and standard deviation, were used to analyze the processed data.

Results

The results from this study show that most pediatric patients (78%) were exposed to off-label use. Half of the medicines prescribed off-label were used for a therapeutic indication other than the one listed in the SmPC. We found that certain medicines were used 100% off-label, and certain diseases were also 100% treated with off-label medications.

Conclusion

Although the study was limited to one center, it deserves attention as it reveals many different aspects of the off-label use of medications in pediatric patients in Bulgaria. Further studies involving a larger number of medical centers are needed to establish more accurate data on off-label prescribing in pediatric patients at a national level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The off-label use of medicines is common, occurring over a wide range of therapeutic areas in both adults and children [1]. According to some studies, the prevalence of off-label use is up to 40% in adults, but occurs more frequently in pediatric population, with a prevalence of up to 90% in some hospitalized pediatric patients [1, 2].

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) defines off-label use as a situation where a medicinal product is intentionally used for a medical purpose not in accordance with the terms of the marketing authorization. This includes different indications in terms of medical condition, different groups of patients (e.g., different age group), different routes or methods of administration, or different posology than those approved and described in the authorized product information [3].

This definition by the EMA places physicians in a very conflicting situation. If a physician intentionally prescribes medicine to a patient without the necessary authorization, it can be interpreted as a violation of the law in Bulgaria and all other EU countries that have no policies or guidelines for off-label use [1]. At the same time, if the physician refuses to prescribe the medicine and treat the patient in need, this is also a violation of the law, of medical ethics, and of the Hippocratic oath [4, 5].

Ethics and law are just some of the problematic aspects of the off-label use of medicines. The greatest concern is patient safety because the off-label use has no regulatory approval or scientifically proven efficacy and safety [6, 7].

Nowadays, with our strict pharmaceutical regulations, such practice seem very unlikely. According to article 6(1) of Directive 2001/83/EC, it is, in principle, prohibited to place a medicinal product on the market without a marketing authorization. It appears that this does not apply to off-label medicine use, as these are authorized medicines used in an unauthorized way. In reality, EU legislation controls market access, but not the way in which medicinal products are used in medical practice [1].

In the last few decades, many initiatives in EU pharmaceutical legislation have been introduced, but somehow off-label use has remained out of the scope of such initiatives. The uncertainty around off-label use has led some EU countries (e.g. UK, Italy, France, Spain, etc.) to further clarify, regulate, and control this practice through guidelines or legislative changes, but most of the EU member states, including Bulgaria, have no clear rules regarding the off-label use of medicines [1, 8].

In 2007, in order to limit the expansion of off-label use and to provide more medicines for the treatment of children, the EMA adopted special Pediatric Regulation 1901/2006/EC. The impact of the regulation was assessed as very positive in the 10-year report published in 2017 and, indeed, an increase was seen in the marketing authorizations for new active substances for treating children [9]. However, the impact is not so positive in regard to off-label use. The medicines commonly used off-label remain largely unstudied, and off-label use in children remains persistently high [10, 11].

The aim of this study is to provide data on the off-label use of medicines in pediatric outpatients in Bulgaria and to contribute to planning actions by the European Commission and EMA to provide harmonized guidelines and to regulate the off-label use of medicines within the EU [12].

Methods

This was a nested, single-center, retrospective, non-interventional database study. We encountered considerable difficulties in collecting the data, because many hospitals and medical centers refused to share information about physician prescriptions. Eventually, we collected the source data from the outpatient center of one of the largest private hospitals in Bulgaria. Data from prescriptions of 360 randomly selected patients (30 per month for 1 year) were collected and recorded by the hospital’s staff. All patients were treated by physicians, who were specialists in pediatrics, from January to December 2016. The source file obtained for analysis contained the following information: patient’s age, sex, diagnosis, prescribed medicines (prescriptions), dosage, and method of administration. For the purpose of this study, patient identification data (patient names, addresses, etc.) were not collected.

To assess the prescriptions, we used the summaries of product characteristics (SmPC) as references. These are publicly available from the Bulgarian Drug Agency website. The SmPC is a legal document approved as part of the marketing authorization of each medicine and serves to inform healthcare professionals on how to use the medicine safely and effectively [13]. Any prescriptions not in accordance with the terms laid down in the SmPCs were considered to be off-label (Table 1).

Non-medicinal products, usually food supplements, were not subject to this assessment (e.g., powder for oral suspension containing probiotic bacteria, physiological sea water nasal micro spray, pediatric cough syrup with ingredients from organic farming, etc.).

All prescriptions were assessed by two independent assessors—a clinical pharmacist and a pharmacovigilance expert—and all discrepancies were addressed to the Bulgarian Drug Agency for final assessment. Descriptive statistics, with absolute frequencies, means, and standard deviation, were used to analyze the processed data. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The differences in the mean values between groups were analyzed with the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Data from all 360 pediatric patients were processed. No information was missing or incomplete. The patients had a mean age of 4 years (range 0.1–18) and were almost equally divided by sex (49% male and 50% female), which corresponds to their distribution in the population. The total number of prescriptions was 1232, which is more than one per patient. The mean number of prescriptions per patient was 4 (range 1–6). The mean number of off-label prescriptions per patient was 1 (range 0–4). The number of off-label and on-label prescriptions, as well as the number of prescriptions between the two sexes, did not differ significantly (p > 0.05). The results in relation to patients and prescriptions are presented in Table 2, where off-label patients are those who received at least one off-label prescription; we did not assess prescriptions for non-medicinal products.

The prescriptions identified as off-label were further analysed to determine the type of off-label use. Some prescriptions were evaluated as off-label in terms of indication as well as for some other reason: dosage (n = 21), administration method (n = 3) and age (n = 3). Final results are presented in Table 3.

The most commonly prescribed off-label medicines are presented in Table 4. Ascorbic acid for parenteral use was the most commonly prescribed off-label medicine, with the off-label use involving administration method in 100% of prescriptions. The second most commonly used off-label medicine, desloratadine syrup, was prescribed off-label with regard to indication. Of note, among the rest, tobramycin/dexamethasone eyedrops, mupirocin nasal gel and budesonide nebulizer suspension were prescribed off-label in 100% of prescriptions; the first was prescribed off-label with regard to the administration method, and the second two with regard to indication.

Diagnoses (n = 51) for which medicines were most commonly prescribed off-label are presented in Table 5. Off-label treatment was considered a treatment where at least one medicine was prescribed off-label. Of note, there were three critical diagnoses for which treatments were 100% off-label: acute pharyngitis, acute non-suppurative otitis and irritable bowel syndrome.

Discussion

Solid arguments exist both in support of and against the off-label use of medicines. In many cases, off-label use is the only alternative for treating certain medical conditions or groups of patients (e.g. rare diseases, cancer diseases, pediatric patients, etc.). Also, as per some recent studies, off-label use provides patients with faster access to therapeutic innovations, increases the number of medicines, and reduces the cost of medical innovations [1, 14, 15]. On the other hand, although in many cases physicians have clinical experience and have evidence to support the off-label use of medicines, their unproven safety can cause serious adverse reactions, organ damage, and even fatal outcomes in some patients, which are the main reasons for concern [16].

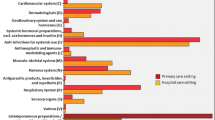

According to some analyses, 10 years after the implementation of Pediatric Regulation 1901/2006/EC, the off-label use of medicines in pediatric patients remains persistently high, with a big gap between therapeutic need and real medical need and practice [10, 11]. The results from this study show that most pediatric patients (78%) were exposed to medicines used off-label, thereby confirming the above conclusions. Over one-third (39%) of prescriptions were for off-label use, which is higher than the range found in the other European population-based studies: Scotland (25%), England (16%), Netherlands (20%), Estonia (31%), Italy (17%) and France (29%) [17, 18].

The most common type of off-label use was with regard to therapeutic indication (51%), followed by dosage (27%). This conflicts with results from the above-mentioned European studies, where dose (39%) and age (32%) were the main types of off-label use. The high rate of off-label use in terms of indication in our study is unusual, because this type was either not found or had a much lower incidence in other similar studies [17, 19]. The most commonly prescribed categories of off-label medicines are similar to those identified in the other European countries (i.e., antihistamines, ß-agonists, antibiotics, etc.) [17, 19]. The exception was ascorbic acid for parenteral use, which was the most commonly prescribed off-label medicine in our study. Ascorbic acid is available on the Bulgarian market as a food supplement for oral use, and the reason physicians prefer an injectable solution is unknown. We consider this practice to be nation specific, as it is well-established practice among Bulgarian physicians.

The 100% off-label use of certain medicines (Table 4) and the 100% off-label treatment of certain diseases (Table 5), are very significant for both health authorities and for market authorization holders and professional medical associations.

Although our study was limited to one center, had a relatively small sample size, and included outpatient data only, it deserves attention as it reveals many different aspects of off-label use that should be further investigated.

Conclusion

The observed frequency of off-label medication use in our study is higher than reported in other European studies. Half of the off-label medicines were used for another therapeutic indication, which differs considerably from findings in other studies. Some medicines (ascorbic acid solution for injection, tobramycin/dexamethasone eyedrops, mupirocin nasal gel, and budesonide nebulizer suspension) and some diagnoses (acute pharyngitis, acute non-suppurative otitis, and irritable bowel syndrome) were particularly affected and deserve special attention. Further studies based on a larger number of medical centers are needed to establish more accurate data on off-label prescribing in pediatric patients at a national level.

References

Weda M, et al. Study on off-label use of medicinal products in the European Union. European Commission; 2017. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/index_en.

Gazarian M, Kelly M, McPhee JR, et al. Off-label use of medicines: consensus recommendations for evaluating appropriateness. Med J Aust. 2006;185(10):544–8.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices: annex I—definitions (Rev 4); 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/pharmacovigilance/good-pharmacovigilance-practices.

Lenk C, Duttge G. Ethical and legal framework and regulation for off-label use: European perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:537–46.

Shiel Jr W. Medical definition of Hippocratic oath. MedicineNet; 2018. Available from: https://www.medicinenet.com/medterms-medical-dictionary/article.htm.

Blanco-Reina E, Muñoz-García A, Cárdenas-Aranzana MJ, et al. Assessment of off-label prescribing: profile, evidence and evolution. Farm Hosp. 2017;41(4):458–69.

Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021–6.

Drenska M, Getov I. Research on approaches for regulation of the “off-label” use of medicinal products in the European Union. Acta Med Bulga. 2017;44(1):17–21.

European Medicines Agency and its Paediatric Committee. 10-year report to the European Commission: general report on the experience acquired as a result of the application of the Paediatric Regulation. European Commission; 2017. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/paediatrics/docs/paediatrics_10_years_ema_technical_report.pdf.

Balan S, Hassali MAA, Mak VSL. Two decades of off-label prescribing in children: a literature review. World J Pediatr. 2018;14(6):528–40.

Wimmer S, Rascher W, McCarthy S, et al. The EU paediatric regulation: still a large discrepancy between therapeutic needs and approved paediatric investigation plans. Paediatr Drugs. 2014;16(5):397–406.

European Medicines Agency. Pharm655. Human Pharmaceutical Committee - Meetings; 2014 March 26; European Commission; Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/index_en.

European Commission. A guideline on summary of product characteristics. European Medicines Agency; 2009. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/product-information/how-prepare-review-summary-product-characteristics#scientific-guidelines-with-smpc-recommendations-section.

Tabarrok A. Assessing the FDA via the anomaly of off-label drug prescribing. Indep Rev. 2000;5(1):25–53.

Miller K. Off-Label drug use: what you need to know. WebMD; 2009. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/off-label-drug-use-what-you-need-to-know#1.

Solère P. Diabetes drug benfluorex linked to thousands of hospitalizations, hundreds of deaths for valvular disease. Medscape; 2010. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/pharmacists.

Gonçalves MG, Heineck I. Frequency of prescriptions of off-label drugs and drugs not approved for pediatric use in primary health care in a southern municipality of Brazil [in Portuguese]. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2016;34(1):11–7.

Chalumeau M, Tréluyer JM, Salanave B, et al. Off label and unlicensed drug use among French office based paediatricians. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83(6):502–5.

Turner S, Longworth A, Nunn AJ, et al. Unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards: prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316(7128):343–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Drenska, V. Grigorova, S. Elitova, E. Naseva, I. Getov have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript.

Ethical approval

This retrospective study is based on recorded data and approval from owners of the data was received.

Data confidentiality

Data confidentiality of all prescription records were respected at all time. Information about the identity of the patients was not collected.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drenska, M., Grigorova, V., Elitova, S. et al. The off-label use of medicines in pediatric outpatients in Bulgaria based on an analysis of their prescription data. Drugs Ther Perspect 35, 391–395 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-019-00638-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-019-00638-4