Abstract

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses opioid-induced respiratory depression. Concentrated naloxone 1.8 mg nasal spray (Nyxoid®) is approved for the emergency treatment of opioid overdose in adults and adolescents aged ≥ 14 years in non-medical and healthcare settings. It is well tolerated, but may lead to opioid withdrawal syndrome in opioid-dependent individuals. Naloxone nasal spray is rapidly absorbed and, relative to reference intramuscular naloxone 0.4 mg, achieves generally similar early exposure, but better maintenance of plasma levels, during the intermediate period (15–120 min).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adis evaluation of naloxone 1.8 mg nasal spray as emergency therapy for opioid overdose

May be used in both non-medical and healthcare settings |

Rapidly absorbed |

Rate of absorption and extent of early exposure generally similar to intramuscular naloxone 0.36 mg |

Maintains plasma naloxone concentrations at twice those of intramuscular naloxone 0.36 mg for 15–120 min |

Well tolerated |

What is the rationale for developing naloxone nasal spray?

Drug-induced deaths, the majority of which are associated with heroin and other opioids, are a major health concern [1, 2]. In Europe, 6000–8000 overdose-related deaths are reported each year, and the average mortality rate due to overdose in 2013 was estimated at 16 deaths per million in the population aged 15–64 years [1]. In recent years, the rate of death from overdose appears to have increased as the average age of the opioid-using population has increased, reflecting the greater risk of drug-induced death in older individuals [1]. For example, among all drug-induced deaths recorded in Europe in 2014, 43% were individuals aged ≥ 40 years and males were more likely than females to die from a drug overdose (males accounted for 77% of all cases) [1]. In the USA, in particular, there has been a large increase in opioid overdose and opioid-related fatalities due to the widespread abuse of prescription and illicit opioids [2].

While drug overdose may result from suicidal intent, the vast majority are accidental [1]. Overdoses can be further categorized into sudden or slow onset. A sudden-onset event typically occurs after intravenous (IV) administration of heroin, whereas a slow-onset overdose is more likely to be associated with oral opioids. In this instance, the patient may appear to be sleeping soundly and friends or family fail to realize the need for emergency intervention [1].

The fatal outcome of an opioid overdose can often be prevented [1]. Data show that 70–80% of all overdose events occur in the presence of another person, who could potentially administer an antidote if available (and if the individual had been instructed on the signs and symptoms of overdose and use of the antidote). Furthermore, in most cases, death from overdose does not occur for 2–3 h, thereby providing a window of opportunity for emergency intervention.

Naloxone is a potent opioid antagonist that reverses opioid-induced respiratory depression [3]. The drug (administered in injectable forms and, more recently, as an intranasal formulation) has been in widespread use in emergency medicine since the 1970s [1]. It is generally well-tolerated when administered in typical doses to opioid-naïve patients [4, 5]. In an attempt to prevent more deaths from drug overdose in non-hospital settings, take-home naloxone programmes have been established and well accepted in many regions worldwide [1, 3].

In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued guidelines on the community management of opioid overdose [6]. The guidelines recommend that access to naloxone and instructions on its administration be provided to individuals likely to witness an opioid overdose (e.g. family members, close friends and people who work with opioid users, such as police officers, firemen, ambulance workers, community drug-treatment workers and outreach workers, as well as healthcare professionals) [6]. Evidence from observational studies indicates that, with appropriate training given to those who are in contact with opioid users, naloxone take-home programmes can be safely implemented and save lives [2, 3, 7,8,9]. Naloxone nasal sprays have been developed with the goal of providing naloxone formulations that are easier than injectable products for non-medical individuals to administer. This review focuses on the use of Nyxoid®, a nasal spray that contains a concentrated formulation of naloxone, which was recently approved in the EU [2, 10]. Each single-dose nasal spray container delivers 1.8 mg of naloxone (equivalent to 2.0 mg of naloxone hydrochloride dihydrate [11]) in 0.1 mL of solution. Hereafter, unless otherwise specified, doses of naloxone, rather than doses of naloxone hydrochloride dihydrate, are provided.

A discussion of the use of other naloxone nasal sprays (e.g. Narcan® [12], which is approved in the USA and Canada) is beyond the scope of this review

How should naloxone nasal spray be used?

Naloxone 1.8 mg/0.1 mL nasal spray is intended for emergency use in adults and adolescents aged ≥ 14 years in non-medical and healthcare settings [10]. Table 1 provides a summary of the prescribing information for naloxone nasal spray in the EU [10].

If an individual is suspected of opioid overdose based on symptoms of respiratory and/or CNS depression, emergency services should be called immediately, as naloxone nasal spray is not a substitute for emergency medical care or basic life support [10, 13]. Naloxone nasal spray should be given after emergency services have been called, and the individual monitored until help arrives. Fig. 1 provides a summary of the instructions for the administration of naloxone nasal spray in non-medical settings [10, 13]. Local prescribing information should be consulted for further information.

What are the pharmacological properties of naloxone nasal spray?

Pharmacodynamic profile

Naloxone is a semisynthetic morphine derivative that acts as a competitive opioid receptor antagonist [10]. The drug has high affinity for opioid receptors where it displaces opioid agonists and partial antagonists. Unlike other opioid antagonists, naloxone does not possess agonist or morphine-like properties and, in the absence of opioids or the agonist effects of other opioid antagonists, it exhibits virtually no pharmacological activity [10]. There is no evidence that naloxone produces tolerance or causes physical or mental dependence [10].

Pharmacokinetic profile

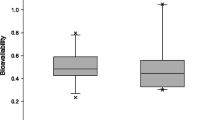

Based on the results of a pharmacokinetic analysis, which identified that concentrated naloxone nasal spray has substantial bioavailability [14], naloxone nasal spray doses of 0.8, 1.8 and 3.6 mg/0.1 mL (equivalent to naloxone hydrochloride dihydrate 1, 2 and 4 mg, respectively) were evaluated in a randomized, crossover study in healthy volunteers [11]. This section focuses on the descriptive results pertaining to the approved 1.8 mg dose of naloxone nasal spray) relative to intramuscular (IM) [primary reference] and IV naloxone (both at a dose of 0.36 mg, which is equivalent to naloxone hydrochloride hydrate 0.4 mg).

After intranasal administration, naloxone was rapidly absorbed and the active substance appeared in the systemic circulation 1 min after administration [10, 11]. The onset of action following intranasal administration can reasonably be expected to occur before the peak plasma concentration (Cmax) is reached. Naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg/0.1 mL achieved mean plasma concentrations > 50% of Cmax by 9 min, and the median time to Cmax was 30 min (range 8–60 min) (Table 1) [11]. The Cmax value achieved with naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg/0.1 mL was more than twofold higher than that achieved with IM naloxone 0.36 mg, and approximately half of that achieved with IV naloxone 0.36 mg (Table 1) [11].

During the first 10 min post-dose, mean naloxone plasma concentrations achieved with naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg were generally similar to those achieved with IM naloxone 0.36 mg [11]. At 15 minutes, mean naloxone plasma concentrations with naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg/0.1 mL were twice those of IM naloxone 0.36 mg and were maintained at more than twice those of the IM dose for the next 2 h.

The duration of action, as indicated by the half-value duration (Table 1), following intranasal administration of naloxone is longer than that following IM naloxone and much longer than that following IV naloxone [11]. Some opioids have a longer half-life than naloxone, and if opioid agonist effects return after those of naloxone have disappeared, repeat doses of naloxone may be needed (Table 1) [10]. The quantity, type and route of administration of the opioid involved in the overdose help determine whether a repeat dose of naloxone is required [10].

The mean absolute bioavailability of concentrated naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg/0.1 mL (47.1% vs IM naloxone 0.36 mg and 46.8% vs IV naloxone 0.36 mg) [11] is higher than that reported with dilute naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg/5 mL (4.0% vs IV administration) [15], and comparable to that with one spray of another concentrated nasal spray containing naloxone 3.6 mg/0.1 mL (44.2% vs IM administration) [12, 16]. It is thought that when the volume of nasal spray is in excess of what can be fully absorbed nasally, there is likely to be loss of drug from the nasal cavity or from post-nasal drip [11]; therefore, the administration of a concentrated formulation of naloxone with a volume of 0.1 mL/dose should prevent the loss of drug relative to more dilute formulations.

Simulation of repeat administration of naloxone nasal spray 1.8 mg/0.1 mL indicated that two doses, as supplied in naloxone 1.8 mg nasal spray packs, would result in naloxone exposure similar to a series of five IM naloxone 0.36 mg doses (i.e. 1.8 mg IM in total; the WHO recommended dose range is 0.36–1.8 mg [6]) [11].

Naloxone is rapidly and extensively metabolized in the liver, mainly by glucuronide conjugation, and is excreted in the urine [10].

What is the clinical effectiveness of naloxone?

Naloxone is highly effective in reversing of opioid overdose [2, 17]. Specific clinical studies in opioid overdose patients have not been performed with naloxone 1.8 mg/0.1 mL nasal spray, as approval was based on a study showing that naloxone nasal spray produces generally similar mean plasma concentrations to those of IM naloxone 0.36 mg [11].

What is the tolerability profile of naloxone?

Naloxone nasal spray is well tolerated [11]. In the randomized, cross-over pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers, no severe adverse events were reported [11]. Eleven naloxone-related adverse events occurred in 9 of 38 patients (24%), and the incidence did not appear to be related to dose.

Based on data regarding the use of all naloxone formulations, nausea is the most common drug-related adverse event, occurring in more than 10% of recipients [10]. Naloxone-related adverse events occurring in 1–10% of recipients include vomiting, dizziness, headache, tachycardia, and hypotension or hypertension. Adverse cardiovascular events with IV or IM naloxone have occurred more frequently in postoperative patients with a pre-existing cardiovascular disease or in those receiving other medicines that produce similar adverse cardiovascular effects. The risk of hypersensitivity reactions is considered to be very rare [10].

Consistent with its mechanism of action, administration of naloxone is typically associated with opioid withdrawal syndrome, which results from the abrupt withdrawal of opioids in individuals physically dependent on the drug [10]. Signs and symptoms of drug withdrawal syndrome include restlessness, irritability, hyperaesthesia, nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal pain, muscle spasms, dysphoria, insomnia, anxiety, hyperhidrosis, piloerection, tachycardia, increased blood pressure, yawning and pyrexia. In some cases, behavioural changes, such as violent behaviour, nervousness and excitement, may also be observed. A correlation between the severity of withdrawal symptoms and a faster onset of opioid antagonism and potency suggests that routes of administration other than IV may be more desirable in some situations [17].

It is not expected that an overdose of naloxone can be administered because of its broad therapeutic margin [10].

What is the current clinical position of naloxone nasal spray?

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses opioid-induced respiratory depression. As with injectable naloxone, the nasal spray can be administered in emergency situations by healthcare and non-healthcare professionals. The nasal spray formulation is potentially easier to use than injectable formulations, particularly with regard to individuals who are likely to witness an opioid overdose, such as family members and close friends, as well as police officers and other first-response personnel. The drug is well tolerated and is virtually devoid of pharmacological effects in opioid-naïve individuals. Opioid withdrawal syndrome may result from the use of naloxone.

Naloxone is rapidly absorbed when administered intranasally as the 1.8 mg/0.1 mL nasal spray, with early exposure to naloxone that is generally similar to that with reference IM naloxone 0.36 mg. From 15–120 min after the intranasal dose, naloxone plasma concentrations are maintained at twice those of IM naloxone, which may be beneficial when the overdose involves highly potent opioids (e.g. fentanyl or carfentanil) that require a higher dose of reversal agents. As the duration of action of some opioids exceeds that of naloxone, sustained plasma naloxone concentrations over the first 2 h may potentially reduce the risk of rebound opioid toxicity that is often observed following an initial response to IV or IM naloxone [11]. Additional doses of naloxone may be administered if the patient does not respond to the first dose or relapses into respiratory depression after responding to the first dose. As with the initial dose, it may be easier to administer subsequent doses of naloxone via a nasal spray rather than via an injection. Each naloxone nasal spray pack contains two single-use nasal sprays (Table 1). Other potential advantages of intranasal versus injectable naloxone include the avoidance of needle-stick injuries and the relatively small amount of training required regarding the use of the device [18].

Fully published cost-effectiveness analyses of the costs and benefits of the distribution of naloxone 1.8 mg/0.1 mL nasal spray for emergency use are not currently available; however, the cost effectiveness of the distribution of other naloxone formulations has been evaluated [19, 20]. For example, a Markov/decision tree model [19] was used to estimate the cost effectiveness of distributing naloxone to adults at risk of heroin overdose (i.e. take-home naloxone) relative to no distribution of take-home naloxone over a lifetime horizon and from a societal perspective in the USA [19] and the UK [20]. In the USA, relative to no distribution, distribution of naloxone (IM or nasal spray kits) to 20% of heroin users was estimated to prevent 6.5% of overdose deaths (one death prevented for every 164 naloxone kits distributed), and was cost effective [base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $US421 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained; 2012 costs] [19]. Similarly, in the UK, the distribution of take-home IM naloxone to 30% of all heroin users was estimated to provide a 6.6% decrease in overdose deaths (preventing 2500 deaths per 200,000 heroin users), and was cost effective (base-case ICER ₤942 per QALY gained; 2016 costs) relative to no distribution [20]. In an exploratory scenario in the UK analysis, the distribution of naloxone 1.8 mg/0.1 mL nasal spray instead of IM naloxone provided additional benefits arising from its ease of use and lack of needlestick injuries; distribution of take-home intranasal naloxone to 30% of all heroin users was predicted to provide a 7.5% decrease in overdose deaths relative to no distribution, and to prevent an additional 324 deaths per 200,000 heroin users relative to the distribution of IM naloxone [20].

Data regarding the effectiveness and safety of naloxone nasal spray in the treatment of opioid overdose in the clinical-practice setting, as well as investigations of its use and cost effectiveness when distributed via various access programmes, are awaited with interest.

References

Strang J, McDonald R. Preventing opioid overdose deaths with take-home naloxone (THN): EMCDDA Insights Report. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA); 2016.

Lewis CR, Vo HT, Fishman M. Intranasal naloxone and related strategies for opioid overdose intervention by nonmedical personnel: a review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:79–95.

McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction. 2016;111(7):1177–87.

Rzasa Lynn R, Galinkin JL. Naloxone dosage for opioid reversal: current evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(1):63–88.

Wermeling DP. Review of naloxone safety for opioid overdose: practical considerations for new technology and expanded public access. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015;6(1):20–31.

World Health Organization (WHO). Community management of opioid overdose. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, et al. Effectiveness of Scotland’s National Naloxone Programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006–10) versus after (2011–13) comparison. Addiction. 2016;111(5):883–91.

Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

Lenton S, Dietze P, Olsen A, et al. Working together: expanding the availability of naloxone for peer administration to prevent opioid overdose deaths in the Australian Capital Territory and beyond. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;34(4):404–11.

European Medicines Agency. Nyxoid (naloxone) 1.8 mg nasal spray, solution in a single-dose container. London: European Medicines Agency; 2017.

McDonald R, Lorch U, Woodward J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of concentrated naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose reversal: phase-I healthy volunteer study. Addiction. 2017;113(3):484–93.

Adapt Pharma Operations Limited. Narcan® (naloxone hydrochloride) nasal spray: US prescribing information. Radnor: Adapt Pharma Operations Limited; 2017.

Mundipharma Corporation Limited. Nyxoid® (naloxone); patient information card. Cambridge: Mundipharma Corporation Limited; 2017.

Mundin G, McDonald R, Smith K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of concentrated naloxone nasal spray over first 30 minutes post-dosing: analysis of suitability for opioid overdose reversal. Addiction. 2017;112(9):1647–52.

Dowling J, Isbister GK, Kirkpatrick CM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal naloxone in human volunteers. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30(4):490–6.

Krieter P, Chiang N, Gyaw S, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties and human use characteristics of an FDA-approved intranasal naloxone product for the treatment of opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166(10):13–20.

Fellows SE, Coppola AJ, Gandhi MA. Comparing methods of naloxone administration: a narrative review. J Opioid Manag. 2017;13(4):253–60.

Weaver L, Palombi L, Bastianelli KM. Naloxone administration for opioid overdose reversal in the prehospital setting: implications for pharmacists. J Pharm Pract. 2018;31(1):91–8.

Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:1–9.

Langham S, Kenworthy JJ, Grieve R, et al. Cost effectiveness of take-home naloxone for the prevention of fatalities from heroin overdose in the UK. [abstract PMH27 + poster]. In: ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress; 2016.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was reviewed by: K.M.S. Bastianelli, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pharmacy Practice, University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy, Duluth, MN, USA; J. Galinkin, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado at Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA; W. Hall, Centre for Youth Substance Abuse Research, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia and the National Addiction Centre, Kings College, London, UK; P. Sacerdote, Department of Pharmacology and Biomedical Sciences, University of Milano, Milano, Italy; D.P. Wermeling, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, Lexington, KY, USA. During the peer review process, Mundipharma Corporation Limited, the marketing-authorization holder of Nyxoid®, was also offered an opportunity to provide a scientific accuracy review of their data. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Conflict of interest

K McKeage and K. A. Lyseng-Williamson are employees of Adis/Springer, are responsible for the article content and declare no conflicts of interest. Additional information about this Adis Drug Review can be found here: http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/8BB99D7021CFB1FD.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKeage, K., Lyseng-Williamson, K.A. Naloxone nasal spray (Nyxoid®) in opioid overdose: a profile of its use in the EU. Drugs Ther Perspect 34, 150–156 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-018-0498-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-018-0498-y