Abstract

The first-in-class β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron is indicated in the EU (Betmiga™), Japan (Betanis™) and several other countries for the management of overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome. Evidence for its use in this setting includes several large phase 3 trials. Compared with placebo, oral mirabegron for 12 weeks reduced the frequency of micturition and generally also that of incontinence, with other benefits including reduced urgency, increased void volume and improved health related quality-of-life (HR-QOL). Mirabegron comparisons versus tolterodine are descriptive; however, in a 12-week powered comparison versus solifenacin in patients dissatisfied with antimuscarinic efficacy, mirabegron did not demonstrate noninferiority in reducing micturition frequency or significantly differ in terms of improving other urinary symptoms. Urinary and HR-QOL benefits of mirabegron were sustained over up to 52 weeks of treatment and the drug was generally well tolerated, with a numerically lower incidence of dry mouth than antimuscarinics. Real-world data support the trial findings and indicate possible persistence and adherence benefits for mirabegron over antimuscarinics. Mirabegron use is not generally restricted by patient age, sex or antimuscarinic treatment status, although data in men (from a phase 4 study and phase 3 trial subanalyses) are variable; additional studies in older and male OAB patients are awaited with interest. Although further longer-term efficacy and tolerability data would be beneficial, current clinical evidence indicates that mirabegron provides an alternative to antimuscarinics for the management of OAB in adults, including those for whom antimuscarinics have proven unsuitable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

First β3-adrenoceptor agonist approved for OAB |

Once-daily oral administration |

Reduces the frequency of micturition, incontinence and urgency and improves HR-QOL |

Sustains these improvements over 52 weeks’ therapy |

Generally well tolerated |

1 Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common syndrome, the prevalence and severity of which increases with age [1]. It is characterized by bothersome urinary symptoms [1], namely urgency (usually with urinary frequency and nocturia), with or without incontinence, in the absence of obvious pathology [2]. OAB pathophysiology is not entirely understood, but is thought to involve micturition reflex abnormalities [3]. Normally, voiding is under voluntary control, with the prefrontal cortex indirectly suppressing voiding until socially appropriate [4]. Until then, urine filling/storage is facilitated by relaxation of the bladder, which occurs via noradrenaline-mediated activation of β3-adrenoceptors (expressed predominantly in bladder tissue) with resultant suppression of detrusor muscle voiding contractions [3, 4]. However, when voiding is desired, parasympathetic nerves release acetylcholine that activates muscarinic receptors (M2 and M3) causing detrusor muscle contraction and urination [3, 4]. In OAB, contractions of the bladder are involuntary, even when there is little urine [5], causing frequent urination with only small void volumes [1].

OAB symptoms considerably impinge upon daily activities, are detrimental to life quality and can be particularly burdensome for older patients [1, 6]. The first pharmacological agents available for the management of OAB were the antimuscarinics [3], and this drug class remains the mainstay of OAB therapy today [6]. However, as these agents are not without limitations (including tolerability and compliance issues), additional treatment options have been sought [3]. Mirabegron, a first-in-class β3-adrenoceptor agonist, is indicated in the EU (Betmiga™) [7], Japan (Betanis™) [8] and several other countries for the management of OAB. This article reviews data relevant to the use of mirabegron in this indication in the EU and Japan and focuses on the dosage recommended in these regions (i.e. 50 mg once daily; Sect. 7).

2 Pharmacodynamic Properties of Mirabegron

Mirabegron is a potent selective agonist of the β3-adrenoceptor [9, 10]. By stimulating β3-adrenoceptors in the bladder, mirabegron likely results in bladder relaxation and thus enhanced urine storage, reductions in bladder contraction and, consequently, fewer unwanted urinations [7, 11].

2.1 Urodynamics

Relaxation of the bladder during filling and a reduction in the frequency of non-voiding activity was seen with mirabegron in men with comorbid lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) [10] in a 12-week placebo-controlled study (n = 200) [12]. Consistent with these findings, bladder storage measures significantly (p ≤ 0.01 vs. baseline) improved over 12 weeks in women with OAB who received mirabegron 50 mg once daily in a noncomparative trial (n = 60) [13]. The benefit of the drug on urine storage is further supported by void volume outcomes in large phase 3 studies in OAB [10] (Sect. 5.1). Moreover, mirabegron had relaxant effects on pre-contracted bladder tissue in vitro [9], reduced the frequency, but not amplitude, of reflex bladder contractions induced by filling in rats [9] and improved storage-phase urodynamics in a rat model of bladder dysfunction [14], with other animal studies/models generally supporting these findings [10, 15]. Further in vitro data suggest mirabegron may promote urethral relaxation through a combination of β3-adrenoceptor agonism and α1A/D-adrenoceptor antagonism [16], although the clinical relevance of this is unknown.

Voiding should not be impeded by β3-adrenoceptor stimulation in the bladder because, in contrast to the urine storage phase (during which sympathetic nerve stimulation predominates), it is controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system [7] (Sect. 1). Indeed, mirabegron 50 mg once daily for 12 weeks did not inhibit voiding function in men with LUTS/BOO, with the drug being noninferior to placebo in terms of adjusted mean changes from baseline in maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) and detrusor pressure at Qmax and not significantly differing from placebo with regard to corresponding changes in post-void residual urine volume [12]. Similar findings were reported over 12 weeks with this dosage of mirabegron in women with OAB, with no significant changes from baseline occurring in any of these measures [13].

2.2 Other Effects

In a thorough QT interval (QTI) study in healthy adults [17], mirabegron at 50 mg (therapeutic dose) or 100 mg (supratherapeutic dose) once daily did not prolong the corrected QTI (QTcI) in either sex, and 200 mg (supratherapeutic dose) once daily did not prolong it in men. However, QTcI prolongation occurred with the 200 mg dosage in women, with the baseline-adjusted difference between mirabegron and placebo exceeding the threshold of regulatory concern (95% CI upper bound > 10 ms) at several timepoints [17]. These findings are consistent with the differences in mirabegron exposure between the sexes (Sect. 3.1). Cautious use of mirabegron is advised in patients with a history of QTI prolongation or taking drugs that prolong the QTI (EU [7] and Japan [8]), as well as in those with hypokalaemia or prone to arrhythmia (Japan) [8].

Cardiostimulant effects have been seen with mirabegron in vitro [18], and increases in pulse rate (PR) [17, 19] and blood pressure (BP) [systolic but not diastolic] [19] have occurred with therapeutic [17] and supratherapeutic [17, 19] doses of the drug in healthy men [17, 19] and women [17], mediated (at least in part) by β1-adrenoceptor stimulation [19]. In adults with OAB, adjusted mean increases from baseline in BP and PR were small with mirabegron 50 mg once daily over 12 weeks in large phase 3 trials (pooled analysis [20] and BEYOND [21]; Sect. 5); these changes were not considered clinically relevant [20, 21] and did not significantly differ from those with solifenacin 5 mg once daily (the active comparator of BEYOND) [21]. ECG and laboratory measures were clinically unremarkable [20], with few mirabegron (two) or solifenacin (four) recipients experiencing clinically significant ECG changes [21]. Longer-term data from a 52-week phase 3 OAB trial of once-daily mirabegron 50 mg (TAURUS; Sect. 5) were consistent with these findings [22]. However, BP should be monitored before and during mirabegron therapy [7, 8]; the drug is contraindicated in patients with severe heart disease in Japan, as PR increases may worsen symptoms [8]. Cardiovascular (CV) safety is discussed in Sect. 6.

In terms of other effects, intraocular pressure of healthy volunteers was not increased by 8 weeks of mirabegron (100 mg once daily) in a placebo-controlled study [23]; however, careful administration of mirabegron and periodical ophthalmological assessment is advised in patients with glaucoma in Japan [8]. Mirabegron has been shown to affect the reproductive organs and function of animals and should consequently be avoided as much as possible in patients of reproductive age in Japan (boxed warning) [8].

3 Pharmacokinetic Properties of Mirabegron

Oral mirabegron is readily absorbed, with maximum plasma concentrations reached 3–5 h after single- or multiple-administration of a 50 mg dose [24,25,26,27]. When administered once daily, steady-state concentrations of mirabegron are attained within 7 days and there is two- to threefold accumulation of the drug [24, 26, 27]. Exposure to mirabegron is reduced when the drug is taken in a fed versus a fasted state [27, 28]. In Japan, mirabegron should be taken after a meal [8]; however, in the EU, mirabegron can be taken with or without food, on the basis of its efficacy and tolerability when taken without food restrictions in patients with OAB in pivotal phase 3 trials [7] (Sects. 5 and 6). The absolute bioavailability of mirabegron 50 mg is 35% [7, 8].

Mirabegron has a large volume of distribution [7, 8, 24, 25] (e.g. ≈ 1670 L at steady state [7]) and partitions into erythrocytes, with concentrations of the drug being twofold greater in erythrocytes than in plasma in vitro [7]. Mirabegron is ≈ 71–77% bound to plasma proteins [7, 8] and is metabolized via several pathways (amide hydrolysis, glucuronidation, N-dealkylation and oxidation) [29] and enzymes [butyrylcholinesterase, UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (including UGT2B7 [30]), CYP3A4, CYP2D6 and possibly alcohol dehydrogenase, although the roles of CYP3A4 and/or CYP2D6 may be limited] [7, 31]. After a single oral dose, unchanged mirabegron is the most abundant moiety circulating in the plasma [29] and there are two major metabolites (each a glucuronide and inactive) [7].

Mirabegron is eliminated in the urine (55%) and faeces (34%), with unchanged mirabegron accounting for 45% and almost all of the drug eliminated via these respective routes [29]. Mirabegron has a terminal elimination half-life of ≈ 50 h, a total body clearance from plasma of ≈ 57 L/h and a renal clearance of ≈ 13 L/h, with the latter occurring via active tubular secretion (predominantly) and glomerular filtration [7].

3.1 Special Patient Groups

Mild or moderate renal impairment does not appear to have a clinically meaningful impact on mirabegron pharmacokinetics [32]; however, severe renal impairment increases exposure to mirabegron considerably [32], necessitating a reduction in dosage [7, 8]. In the EU [7], mirabegron is not recommended for use in patients with end-stage renal disease, as it has not been evaluated in this setting. Similarly, mild hepatic impairment does not appear to alter mirabegron pharmacokinetics to any clinically meaningful extent [32], whereas moderate hepatic impairment increases mirabegron exposure markedly [32] and requires the mirabegron dosage to be reduced [7, 8]. Mirabegron is not recommended (EU) [7] or is contraindicated (Japan) [8] in patients with severe hepatic impairment, given the drug has not been studied in these patients [7] and the increased risk of excessive mirabegron exposure [8]. However, EU recommendations alter if strong CYP3A inhibitors are being used, with mirabegron requiring a dosage reduction for mild or moderate renal impairment or mild hepatic impairment and not being recommended in severe renal or moderate hepatic impairment [7].

No adjustments in mirabegron dosage are recommended on the basis of race, CYP2D6 polymorphisms, age or sex [7, 8]. However, exposure to mirabegron is higher in women than men [7, 8, 25,26,27] (due to bodyweight and bioavailability differences) and, despite being generally similar regardless of age [7, 26], was 1.32-fold higher in older versus younger Japanese OAB patients (aged ≥ 65 vs. < 65 years), necessitating careful use of mirabegron in the elderly in Japan [8].

4 Drug Interactions

Mirabegron is a substrate of various enzymes (Sect. 3), including transporters such as OCT1, OCT2, OCT3 and P-gp [7]. Plasma concentrations of mirabegron are reduced by drugs that induce CYP3A or P-gp; however, the mirabegron dosage does not need adjusting when these inducers (e.g. rifampicin) are being used concomitantly at therapeutic concentrations in the EU [7], although care is advised in Japan [8]. Care is also recommended in Japan if coadministering mirabegron with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (some of which also inhibit P-gp), as mirabegron blood concentrations may increase [8]; increased exposure to mirabegron may increase PR [7]. Moreover, combined use of mirabegron and catecholamines may increase adrenergic nerve stimulation and requires care in Japan [8].

Mirabegron inhibits CYP2D6 moderately [7], and may thus increase exposure to drugs that are CYP2D6 substrates [7, 8]. In the EU, caution is required when coadministering mirabegron with drugs that are metabolized significantly by CYP2D6 and have narrow therapeutic indices (e.g. thioridazine, type 1C antiarrhythmics and tricyclic antidepressants) or CYP2D6 substrates that require individual dose titration [7]. Similar recommendations apply in Japan, although mirabegron is contraindicated for use in combination with certain type 1C antiarrhythmics (flecainide acetate and prophenone hydrochloride) [8].

Mirabegron inhibits P-gp, albeit weakly, and may therefore increase exposure to P-gp substrates, a property that requires consideration in the EU if mirabegron is to be used in conjunction with dabigatran and other sensitive P-gp substrates [7]. Serum concentrations of digoxin (a P-gp substrate) should be monitored in patients receiving concomitant mirabegron in the EU [7] or Japan [8]. Mirabegron is also a weak inhibitor of CYP3A [7].

5 Therapeutic Efficacy of Mirabegron

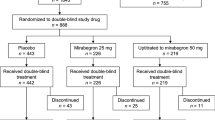

This section focuses on the efficacy of mirabegron 50 mg once daily in treating OAB in adults, as evaluated in several large (n > 400) multicentre clinical trials of 12 or 52 weeks’ duration; large real-world studies (n > 1000 mirabegron recipients) and analyses of pooled clinical trial data are also discussed. Most clinical trials were randomized, double-blind, placebo- and/or active comparator-controlled studies (except one, which was open-label and noncomparative [33]) and were phase 3 unless stated otherwise. Among the trials with active comparator arms, only one (BEYOND) was powered to make statistical comparisons between mirabegron and the active agent (solifenacin) [21]. Most trials were multinational [21, 22, 34,35,36], with some conducted in USA/Canada [37], Asia [36] or specifically Japan [33, 38].

The clinical trials enrolled men and women (or just men [39]) with OAB symptoms for ≥ 3 [21, 22, 34,35,36,37, 39] or ≥ 6 [33, 38] months who (after completing a run-in phase of 1–2 weeks) experienced an average of ≥ 8 micturition episodes/24 h and either ≥ 3 urgency episodes [21, 22, 34, 35, 37] or ≥ 1 urgency and/or ≥ 1 urgency incontinence episode/24 h [33, 36, 38] during a 3-day pre-treatment period. Common exclusion criteria among the studies included stress (or predominantly stress) incontinence, average daily urine volume > 3000 mL and severe hypertension. Across trials, patients were predominantly women (64–85% in mixed-sex studies) and had a mean age of 54–61 years. Where specified, the mean OAB duration was 58–113 months and, in trials other than BEYOND (in which all patients had received antimuscarinics previously; Sect. 5.3), 48–65% of patients had previously received pharmacological OAB therapy, discontinuing most often because of insufficient benefit.

5.1 Urinary Symptoms

Mirabegron improved micturition frequency, and also generally improved incontinence frequency, in adults with OAB in five short-term trials. After 12 weeks’ treatment, the daily number of micturition episodes (primary endpoint in all studies) was significantly reduced with mirabegron relative to placebo [34,35,36,37,38], as was the daily number of incontinence episodes (primary endpoint in all but two studies) in most trials [34, 35, 37, 38] (Table 1). Mirabegron recipients also had significant reductions in the daily number of micturitions associated with grade 3–4 urgency and voided a significantly greater volume of urine per micturition than placebo recipients; however, only one [37] of the three [36,37,38] trials that assessed nocturia frequency found it to be significantly reduced with mirabegron versus placebo (Table 1). The findings of the five trials are generally supported by a pre-specified analysis [40] of pooled data from three of the studies [34, 35, 37], with significant benefit seen with mirabegron versus placebo for all of the discussed parameters, including nocturia (Table 1).

Improvements in the primary efficacy measures of individual trials were evident with mirabegron versus placebo at the first assessment (i.e. at week 4 of treatment) and sustained thereafter [34,35,36,37,38], with similar findings being reported with mirabegron in the prespecified pooled analysis [41].

Among incontinent patients, reductions in the frequency of incontinence and urgency episodes with mirabegron versus placebo appeared to increase with increasing baseline incontinence severity, whereas improvements in micturition frequency and void volume showed little variation across the assessed populations. This post hoc analysis [42] of the pooled data already discussed (i.e. from three 12-week trials [34, 35, 37]) included patients with ≥ 1 (n = 1740) or an average of ≥ 2 (n = 906) or ≥ 4 (n = 392) incontinence episodes/24 h at baseline.

Longer-term treatment with mirabegron for 52 weeks provided sustained improvements in key OAB symptoms in two additional studies (Table 2) [22, 33].

In contrast to mirabegron, tolterodine did not significantly differ from placebo for most urinary outcomes in the two 12-week trials that made such statistical comparisons (Table 1) [34, 36]. However, urinary symptom improvements did not markedly differ between mirabegron and tolterodine in the comparative 52-week study, although between-group statistical comparisons were not performed (Table 2) [22].

5.2 Health-Related Quality of Life and Other Outcomes

Improvements in health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) were seen with mirabegron in most short-term studies. In the three trials that used the OAB questionnaire (OAB-q), 12 weeks’ treatment with mirabegron was associated with significant (p < 0.05 vs. placebo) adjusted mean improvements in symptom bother score [34, 35, 37], as well as three [43] or four [37] of the five OAB-q HR-QOL domain scores (coping, concern, total HR-QOL and/or sleep, but not social), where specified. There were also significant (p < 0.05 vs. placebo) adjusted mean improvements in the Patient Perception of Bladder Condition questionnaire (PPBC) score in two [34, 37] of the three [34, 35, 37] trials. The benefit of mirabegron, as measured by these instruments, was corroborated in a post hoc analysis [44] of pooled data (see Sect. 5.1 for details) and was generally also evident in patients with incontinence at baseline, where reported [43].

Among the two 12-week trials that assessed HR-QOL with the King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ), one reported significant (p < 0.05 vs. placebo) mean improvements with mirabegron in most domains (incontinence impact, role, physical and social limitations, emotions, sleep/energy and severity, but not personal relationships or general health perceptions) [38], whereas the other trial reported no statistically significant benefit with the drug (vs. placebo) [36]. However, mean changes from baseline in most domain scores exceeded the clinically important difference of 5 points with mirabegron in each study [36, 38].

Treatment satisfaction [assessed by visual analogue scale (VAS)] significantly (p < 0.05) improved with mirabegron versus placebo over 12 weeks, where reported [34, 35, 37], including in patients with baseline incontinence [43], with the prespecified analysis of pooled data supporting these findings [40]. Mirabegron recipients also had numerical improvements versus placebo recipients in the absenteeism, presenteeism and work and activity impairment components of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment-Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SHP) questionnaire (no statistical analyses performed) [43].

Longer-term treatment with mirabegron for 52 weeks was associated with sustained improvements in HR-QOL (OAB-q [22], PPBC [22] and KHQ [33] scores) and treatment satisfaction (VAS) [22].

In tolterodine control arms, 12 weeks’ treatment was associated with significant (p < 0.05) improvements in OAB-q symptom bother score [34] (but not OAB-q [43] or KHQ [36] HR-QOL domain scores), disease perception (PPBC) [34] and treatment satisfaction (VAS) [34], and numerical improvements in absenteeism and activity impairment (but not presenteeism or work impairment) [WPAI-SHP] [43] versus placebo. In the 52-week comparative study, improvements in HR-QOL (OAB-q and PPBC) and treatment satisfaction (VAS) with tolterodine were not markedly different from those seen with mirabegron, although statistical comparisons were not performed [22].

5.3 Versus Solifenacin

The phase 3b BEYOND study enrolled adults with OAB who were dissatisfied with the efficacy of their last antimuscarinic (which could have been any, except solifenacin); 57% of patients had received just one antimuscarinic [21]. Mirabegron did not meet the prespecified noninferiority criteria versus solifenacin for improvements in daily micturition frequency over 12 weeks of treatment in this trial (primary endpoint; Table 1). There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups for other urinary symptom measures, including the daily frequency of incontinence, grade 3–4 urgency and nocturia episodes (Table 1). Mirabegron had significantly (p < 0.05) more favourable adjusted mean changes in some HR-QOL measures (OAB-q symptom bother and PPBC, but not OAB-q total HR-QOL) and all treatment satisfaction measures (VAS and Treatment Satisfaction-questionnaire Likert scale); however, these statistical differences versus solifenacin were not considered to be clinically relevant [21].

5.4 Specific Patient Groups

The clinical benefit of mirabegron in adults with OAB was more notable in those who had received antimuscarinics previously versus those who had not, both in a prespecified subanalysis of pooled data (see Sect. 5.1 for details) [40] and in a post hoc analysis [45] of one study [34]. For instance, over 12 weeks in the pooled analysis [40], the adjusted mean change from baseline in incontinence episodes/24 h was − 1.5 with mirabegron versus − 0.9 with placebo in antimuscarinic-experienced patients and − 1.5 versus − 1.4 in antimuscarinic-naïve patients. Corresponding changes in micturition episodes/24 h were − 1.7 versus − 0.9 in the experienced group and − 1.8 versus − 1.5 in the naïve group.

Mirabegron also appears to reduce the frequency of incontinence and micturition episodes in older OAB patients, according to a prospective analysis [46] of the pooled data. Differences between mirabegron and placebo for adjusted mean changes from baseline in incontinence episodes/24 h and micturitions/24 h were − 0.66 and − 0.62 in patients aged ≥ 65 years (n = 700 and 1003 evaluable for respective measures) and − 0.65 and − 0.59 in those aged ≥ 75 years (n = 223 and 303).

Mirabegron has also been evaluated specifically in male OAB patients in various trials/analyses. In a phase 4 study (MIRACLE) [39], mirabegron (n = 308) and placebo (n = 154) did not significantly differ in the mean change from baseline in daily micturition frequency at 12 weeks (1.6 vs. 1.5) [primary endpoint], although recipients of the drug had more favourable (p ≤ 0.02) mean changes in OAB Symptom Scores (total, urgency and urgency incontinence) and most International Prostate Symptom Scores (storage and urgency, but not quality of life). The findings of a prespecified analysis of the pooled phase 3 data were also mixed, with mirabegron (n = 168–382) significantly reducing the mean daily frequency of micturition, but not incontinence or grade 3 or 4 urgency episodes versus placebo (n = 154–362) [latter measure was post hoc] [47]. In terms of active comparisons, male patient data from BEYOND [47] supported the overall findings of the trial (Sect. 5.3), with mirabegron (n = 58–222) and solifenacin (n = 59–221) not significantly differing in terms of adjusted mean improvements in daily micturition, incontinence or grade 3 or 4 urgency frequency over 12 weeks (measures other than micturition were post hoc).

5.5 Real-World Studies

Efficacy has been observed with mirabegron in the real-world setting in two large prospective Japanese post-marketing studies. Mirabegron was considered an effective OAB treatment in the majority (81%) of recipients after 12 [48] and 52 [49] weeks of therapy (n = 9394 and 1091 evaluable), with significant improvements in urinary symptoms (measured by OAB Symptom Scores) evident with the drug over these periods (n = 4153 and 502 evaluable) [48, 49]. Of note, in a post hoc analysis [50] of the 12-week study [48], mirabegron was slightly (albeit significantly) less effective in patients aged ≥ 75 years than in those aged < 75 years for some measures, including the proportion of patients who achieved a minimally clinically important change in total OAB Symptom Score over this period (61 vs. 66%; p < 0.001).

In various retrospective analyses of pharmacy/medical/insurance claims (Japan [51], Canada [52], USA [53]) and primary care research (UK [54]) databases (n = 3970–71,980), rates of treatment persistence after 52 weeks were relatively low with mirabegron (14–38%) as well as with antimuscarinics (5–25%), although significantly (p ≤ 0.002) favoured mirabegron over antimuscarinics where specified [54]. A large Japanese post-marketing study reported 66% persistence with mirabegron at 52 weeks, although this may have been due to aspects of the study’s prospective design (e.g. frequent follow ups) [49].

When adherence was assessed in some of the retrospective studies, 18–44% of mirabegron recipients versus 7–35% of antimuscarinic recipients were adherent to therapy over 52 weeks [i.e. were adherent ≥ 80% of the time, as measured by proportion of days covered [53] or medication possession ratio (MPR) [51, 54]], with the difference being significant (p ≤ 0.02) where specified [54]. Adherence measured by median [52] or mean [54] MPR was also significantly (p ≤ 0.004) more favourable with mirabegron than all [52] or most [54] assessed antimuscarinics.

6 Tolerability of Mirabegron

Oral mirabegron was generally well tolerated for up to 52 weeks in adults with OAB in the pivotal clinical trials [21, 22, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39] and large post-marketing studies [48,49,50] discussed in Sect. 5, with this section focusing on pooled data (where possible) and the recommended dosage of 50 mg once daily.

In a prospective analysis [20] of pooled data from three 12-week phase 3 trials [34, 35, 37], the tolerability profile of mirabegron was generally similar to that of placebo (Table 3). In each of these treatment groups, adverse events (AEs) considered to be treatment related (i.e. TRAEs) occurred in < 20% of patients, were rarely serious (≤ 1% of patients) and caused fewer than 3% of patients to discontinue treatment. Hypertension and headache were the TRAEs that occurred most frequently with mirabegron (although their incidence did not markedly differ from that seen with placebo; Table 3) and led to the most mirabegron discontinuations [20].

Mirabegron had a generally similar tolerability profile to that of the antimuscarinic agents tolterodine [20] and solifenacin [21] over 12 weeks in this pooled analysis [20] and BEYOND [21] (Table 3). In terms of the most common treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) [21] or TRAEs [20], mirabegron did not differ markedly from solifenacin for headache and constipation or from tolterodine for hypertension, headache and constipation, although the incidence of dry mouth (the most common event with each of the antimuscarinics) was 1.9- to 10.6-fold lower with mirabegron (Table 3) [20, 21].

The longer-term tolerability profile of mirabegron was generally consistent with that seen with the drug in 12-week trials. For example, in the largest [22] of the two 52-week studies [22, 33], the proportion of patients who experienced TEAEs, serious TEAEs or discontinued treatment because of TEAEs was 59.7, 5.2 and 6.4%, respectively, with mirabegron (vs. 62.6, 5.4 and 6.0% with tolterodine) [n = 812 in each treatment group]. Mirabegron was generally similar to tolterodine in terms of the nature and incidence of the most common TEAEs, which included hypertension (9.2 vs. 9.6%), urinary tract infection (5.9 vs. 6.4%) and headache (4.1 vs. 2.5%), although the incidence of dry mouth (the second most common TEAE with tolterodine) was 3.1-fold lower with mirabegron (2.8 vs. 8.6%) [22]. The TRAEs that most commonly led to mirabegron discontinuation were headache and constipation [20].

The tolerability profile of mirabegron did not appear to be markedly impacted by age, race or sex in the pooled analysis of 12-week trials [20], or the large 52-week study [20], with its tolerability in male patients over 12 weeks being further supported by MIRACLE [39] and subanalyses of BEYOND (post hoc) and the pooled data [47].

6.1 Adverse Events of Special Interest

Urinary retention was rare with mirabegron over 12 weeks’ therapy in the pooled analysis [20] and BEYOND [21], occurring with an incidence of 0.1% [20, 21] versus 0.5% with placebo [20], 0.6% with tolterodine [20] and 0.1% with solifenacin [21]. All cases resolved spontaneously and none were acute in BEYOND [21], whereas in the pooled analysis [20], acute urinary retention occurred in 0.1% of mirabegron, 0.2% of placebo and 0.6% of tolterodine recipients, with all those affected in the mirabegron and tolterodine groups consequently discontinuing treatment. Findings were similar longer term, with urinary retention reported in 0.1% of mirabegron and 0.4% of tolterodine recipients over 52 weeks’ treatment in TAURUS; no cases were acute with mirabegron versus one case with tolterodine that required catheterization and permanent discontinuation of treatment [22]. However, mirabegron requires cautious use in patients with clinically significant BOO or taking antimuscarinics for OAB in the EU [7]. In Japan, mirabegron should be discontinued if symptoms of urinary retention occur and the drug should not be used in combination with anticholinergic OAB drugs [8].

In terms of CV profile, the incidence of independently-adjudicated major adverse CV events (MACE), as well as TEAEs, serious AEs and CV-adjudicated AEs involving ventricular arrhythmia or QTI prolongation, was low over 12 weeks with mirabegron, placebo or tolterodine in the pooled analysis (e.g. QTI prolongation AEs occurred in 0, 0 and 0.4% of patients in the respective groups) [20]. Similarly, CV AEs (including QTI prolongation, cardiac arrhythmia/failure, tachycardia and atrial fibrillation) also occurred with low incidence with mirabegron and solifenacin over 12 weeks in BEYOND (0.1–1.7 vs. 0–1.8%) [21]. Longer-term data support these findings, with mirabegron being associated with a low incidence of adjudicated MACE (0.7 vs. 0.5% with tolterodine), QTI prolongation (0.4 vs. 0.4%) and cardiac arrhythmia (3.9 vs. 6.0%) over 52 weeks of treatment in TAURUS [22]. However, mirabegron is contraindicated in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension (EU) [7], as cases of serious hypertension (including hypertensive crisis) have been reported with the drug, some of which had a clear temporal relationship to its use [55].

7 Dosage and Administration of Mirabegron

Mirabegron tablets are indicated for the symptomatic treatment of urgency, increased micturition frequency and/or urgency incontinence in adults with OAB syndrome in the EU [7], and for urgency, urinary frequency and urge urinary incontinence in OAB in Japan [8]. The recommended dosage is 50 mg taken orally once daily with or without food [7] or after a meal [8]. Consult local prescribing information for details of use in special patient populations, drug interactions, contraindications, and other warnings and precautions.

8 Place of Mirabegron in the Management of Overactive Bladder Syndrome

Relieving symptoms to optimize quality of life is the main aim of OAB management and several therapeutic options are available to achieve this goal [1, 4]. Conservative approaches (e.g. behavioural/lifestyle interventions and/or physical therapy) are generally the first port-of-call, with pharmacotherapy initiated if symptom improvement remains inadequate [1, 56, 57]. Other treatment options are more invasive (e.g. neuromodulation, botulinum toxin injection) and are generally reserved for select patients, including those with OAB refractory to first- and second-line therapies [1, 56, 57].

Pharmacotherapy is a mainstay treatment for OAB [4] and has been dominated for many years by antimuscarinics (e.g. tolterodine, oxybutynin, solifenacin) [3], which reduce detrusor contractions and urgency sensations by inhibiting M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in the bladder detrusor muscle and urothelium [6]. However, as many patients stop taking these drugs (e.g. 43–83% within first 30 days in one medical claims review) [58], often because of unmet treatment expectations and AEs [59], there has been a clear need for additional non-invasive treatments that could delay consideration of more invasive procedures. Mirabegron is a relatively recent (but widely used [3]) pharmacological agent that has expanded the non-invasive treatment options available for managing OAB. As a β3-adrenoceptor agonist, it was the first drug with a new mechanism of action to be approved for use in this setting in decades [60], appearing to act primarily by relaxing the bladder to increase its storage of urine without impeding voiding (Sect. 2.1) or increasing the risk of urinary retention (Sect. 6.1).

Mirabegron is currently the only β3-adrenoceptor agonist approved for managing OAB and, like antimuscarinics, is a symptomatic treatment (i.e. does not modify or cure OAB). Its efficacy in alleviating OAB symptoms in adults has been demonstrated in several large phase 3 trials and real-world studies of up to 52 weeks’ duration (Sect. 5), with its clinical benefit versus placebo in phase 3 trials (Sect. 5.1) generally being mirrored by improvements in HR-QOL and other patient-reported outcomes (Sect. 5.2). As changes in micturition and/or incontinence frequency were the primary endpoints of these studies, robust trials primarily designed to evaluate urinary urgency/urgency-related outcomes would be of interest.

Benefits of mirabegron versus placebo were modest but generally consistent with those seen with standard antimuscarinics [15]. Although some phase 3 trials included a tolterodine control arm, BEYOND is currently the only large trial powered to compare mirabegron with another active agent (other such studies would be beneficial). In this 12-week study in patients dissatisfied with the efficacy of their last antimuscarinic, mirabegron did not demonstrate noninferiority versus solifenacin in reducing micturition frequency, although the drugs provided similar improvements in other urinary outcomes and did not differ to any clinically relevant extent in HR-QOL/satisfaction benefits (Sect. 5.3). However, some of the trial’s limitations, such as the exclusion of patients dissatisfied with the tolerability of antimuscarinics, need to be considered when interpreting these findings.

Tolerability (like efficacy) is an important determinant of patient adherence to OAB therapy [1]. Mirabegron for up to 52 weeks was generally well tolerated in clinical trials, displaying a profile generally similar to that of placebo and, for the most part, antimuscarinics (Sect. 6). Among the AEs associated with antimuscarinics, dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision and cognitive impairment are some of the most bothersome [3, 61], with dry mouth being one of the most common reasons for antimuscarinic discontinuation [62]. Mirabegron appeared to have a lower incidence of dry mouth than antimuscarinics (Sect. 6), which could potentially improve patient adherence/persistence to treatment [61]. Indeed, in the real-world setting, persistence and adherence benefits were evident with mirabegron versus antimuscarinics in patients with OAB, although rates were still relatively low (Sect. 5.5).

The CV safety of OAB treatments is also important to consider, as CV comorbidities are common among OAB patients [63]. Antimuscarinics have the potential for CV AEs, such as QTI prolongation, torsade de pointes and increased BP and PR, because of the roles M2 and M3 receptors play in mediating PR and vasodilation [6]. However, clinically significant PR or BP effects rarely occur with these agents [6] and their overall CV safety is considered to be good [64]. Currently available data indicate that mirabegron is also likely to have generally good overall CV safety, with initial concerns about the potential for clinically relevant off-target effects at β-adrenoceptors in CV tissues being largely unsubstantiated [64, 65] (Sects. 2.2 and 6.1). However, there are CV warnings and precautions for mirabegron, including a contraindication in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension (as serious hypertensive events have occurred with the drug; Sect. 6.1). Longer-term and pharmacovigilance data are needed to determine the tolerability (as well as the efficacy) of mirabegron beyond 52 weeks; however, prospective routine surveillance [66] and a retrospective analysis of administration claims databases [67] have found no increased risk of acute myocardial infarction or stroke with mirabegron versus oxybutynin to date in the USA.

Mirabegron use is generally not restricted by patient age, sex or antimuscarinic treatment status [7, 8]. Subanalyses of phase 3 trials found benefit with the drug in patients who had, or had not, received antimuscarinics previously (although benefit was less notable in naïve patients due to them having a greater placebo effect, as has been seen in some antimuscarinic trials) or were of an older age (Sect. 5.4). Data from a phase 4 study of mirabegron in OAB patients aged ≥ 65 years (NCT02216214) are awaited with interest, particularly as the adverse cognitive effects of antimuscarinics can limit their use in older patients [61] (although CNS AE incidence may be determined more by a patient’s total anticholinergic burden than any single drug per se [6]). Although most mirabegron trial participants were women, limited data indicate some outcomes may be improved in men (Sect. 5.4). Additional robust studies are therefore needed in men, with phase 4 trials already underway (NCT02757768) or recently reporting promising findings [68] with mirabegron in men with OAB also taking the α-blocker tamsulosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH); however, for patients with BPH or other lower urinary tract obstructive diseases in Japan, treatment (e.g. with an α-blocker) should be the priority.

Further powered head-to-head active comparisons would also be of interest, although in mixed treatment comparisons of data from 44 randomized, controlled OAB trials (27,309 patients), mirabegron 50 mg once daily displayed similar efficacy to most antimuscarinics (only solifenacin 10 mg once daily was more effective) and caused less dry mouth [69].

Treatment guidelines relevant to the management of OAB include those specific to the condition [1, 56] and those for urinary incontinence [57, 70], some of which include OAB-specific recommendations [57]. Mirabegron is recommended by NICE as an option for managing OAB symptoms when antimuscarinics are intolerable, clinically ineffective or contraindicated [71]. However, more recent guidelines by the EAU recommend mirabegron (grade B recommendation) and antimuscarinics (grade A) as first-line pharmacological options for treating urgency urinary incontinence [70], with US [1] and Canadian [56] OAB guidelines making similar recommendations. Notably, treating OAB with mirabegron may lower healthcare resource use, work productivity losses and the overall cost of treatment compared with antimuscarinics, according to a UK pharmacoeconomic analysis [72]. Moreover, in cost-utility analyses, mirabegron was estimated to be a cost-effective treatment option for OAB versus standard oral antimuscarinics from the perspective of the UK NHS [73, 74], although fesoterodine was determined to be cost effective versus mirabegron for OAB with urge urinary incontinence from a Spanish NHS perspective [75]. Further cost-utility data would be beneficial.

To conclude, although further longer-term efficacy and tolerability data would be beneficial, current clinical evidence indicates that mirabegron offers an alternative to antimuscarinics for the management of OAB in adults, including those for whom antimuscarinics have proven unsuitable, and may thus delay consideration of more invasive treatment options.

Data Selection Mirabegron: 461 records identified

Duplicates removed | 86 |

Excluded during initial screening (e.g. press releases; news reports; not relevant drug/indication; preclinical study; reviews; case reports; not randomized trial) | 11 |

Excluded during writing (e.g. reviews; duplicate data; small patient number; nonrandomized/phase I/II trials) | 289 |

Cited efficacy/tolerability articles | 28 |

Cited articles not efficacy/tolerability | 47 |

Search Strategy: EMBASE, MEDLINE and PubMed from 2013 to present. Previous Adis Drug Evaluation published in 2013 was hand-searched for relevant data. Clinical trial registries/databases and websites were also searched for relevant data. Key words were Mirabegron, Betanis, Betmiga, YM178, overactive bladder. Records were limited to those in English language. Searches last updated 2 May 2018 | |

References

Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015;193(5):1572–80.

International Continence Society. Terminology: overactive bladder (OAB, urgency) syndrome. 2010. http://www.ics.org/terminology/23. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Thiagamoorthy G, Cardozo L, Robinson D. Current and future pharmacotherapy for treating overactive bladder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(10):1317–25.

Palmer CJ, Choi JM. Pathophysiology of overactive bladder: current understanding. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2017;12:74–9.

Mayo Clinic. Overactive bladder. 2018. http://www.mayoclinic.org. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Wagg A, Nitti VW, Kelleher C, et al. Oral pharmacotherapy for overactive bladder in older patients: mirabegron as a potential alternative to antimuscarinics. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(4):621–38.

European Medicines Agency. Betmiga prolonged-release tablets: summary of product characteristics. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Astellas Pharma Inc. Betanis tablet: Japanese prescribing information. Tokyo: Astellas Pharma Inc.; 2015.

Takasu T, Ukai M, Sato S, et al. Effect of (R)-2-(2-aminothiazol-4-yl)-4’-{2-[(2-hydroxy-2-phenylethyl)amino]ethyl} acetanilide (YM178), a novel selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist, on bladder function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321(2):642–7.

European Medicines Agency. Assessment report: Betmiga. 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed 19 May 2018.

European Medicines Agency. EPAR summary for the public: Betmiga. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Nitti VW, Rosenberg S, Mitcheson DH, et al. Urodynamics and safety of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron in males with lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1320–7.

Matsukawa Y, Takai S, Funahashi Y, et al. Urodynamic evaluation of the efficacy of mirabegron on storage and voiding functions in women with overactive bladder. Urology. 2015;85(4):786–90.

Sawada N, Nomiya M, Hood B, et al. Protective effect of a β3-adrenoceptor agonist on bladder function in a rat model of chronic bladder ischemia. Eur Urol. 2013;64(4):664–71.

Sacco E, Bientinesi R, Tienforti D, et al. Discovery history and clinical development of mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence. Exp Opin Drug Discov. 2014;9(4):433–48.

Alexandre EC, Kiguti LR, Calmasini FB, et al. Mirabegron relaxes urethral smooth muscle by a dual mechanism involving β3-adrenoceptor activation and α1-adrenoceptor blockade. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(3):415–28.

Malik M, van Gelderen EM, Lee JH, et al. Proarrhythmic safety of repeat doses of mirabegron in healthy subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-, and active-controlled thorough QT study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(6):696–706.

Mo W, Michel M, Kaumann A, et al. Cardiostimulant effects of mirabegron in human atrium and ventricle in vitro [abstract no. 571]. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(Suppl 2):S291.

van Gelderen M, Stolzel M, Meijer J, et al. An exploratory study in healthy male subjects of the mechanism of mirabegron-induced cardiovascular effects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(12):1534–44.

Nitti VW, Chapple CR, Walters C, et al. Safety and tolerability of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron, for the treatment of overactive bladder: results of a prospective pooled analysis of three 12-week randomised phase III trials and of a 1-year randomised phase III trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(8):972–85.

Batista JE, Kolbl H, Herschorn S, et al. The efficacy and safety of mirabegron compared with solifenacin in overactive bladder patients dissatisfied with previous antimuscarinic treatment due to lack of efficacy: results of a noninferiority, randomized, phase IIIb trial. Ther Adv Urol. 2015;7(4):167–79.

Chapple CR, Kaplan SA, Mitcheson D, et al. Randomized double-blind, active-controlled phase 3 study to assess 12-month safety and efficacy of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist, in overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2013;63(2):296–305.

Novack GD, Lewis RA, Vogel R, et al. Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled study to assess the ocular safety of mirabegron in healthy volunteers. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29(7):674–80.

Iitsuka H, Tokuno T, Amada Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist for treatment of overactive bladder, in healthy Japanese male subjects: results from single- and multiple-dose studies. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(1):27–35.

Eltink C, Lee J, Schaddelee M, et al. Single dose pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist for treatment of overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50(11):838–50.

Krauwinkel W, van Dijk J, Schaddelee M, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist: results from two phase I, randomized, multiple-dose studies in healthy young and elderly men and women. Clin Ther. 2012;34(10):2144–60.

Iitsuka H, van Gelderen M, Katashima M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist for treatment of overactive bladder, in healthy East Asian subjects. Clin Ther. 2015;37(5):1031–44.

Lee J, Zhang W, Moy S, et al. Effects of food intake on the pharmacokinetic properties of mirabegron oral controlled-absorption system: a single-dose, randomized, crossover study in healthy adults. Clin Ther. 2013;35(3):333–41.

Takusagawa S, van Lier JJ, Suzuki K, et al. Absorption, metabolism and excretion of [14C]mirabegron (YM178), a potent and selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist, after oral administration to healthy male volunteers. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(4):815–24.

Konishi K, Tenmizu D, Takusagawa S. Identification of uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferases responsible for the glucuronidation of mirabegron, a potent and selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist, in human liver microsomes. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-017-0450-x.

Lee J, Moy S, Meijer J, et al. Role of cytochrome p450 isoenzymes 3A and 2D6 in the in vivo metabolism of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(6):429–40.

Dickinson J, Lewand M, Sawamoto T, et al. Effect of renal or hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of mirabegron. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(1):11–23.

Yamaguchi O, Ikeda Y, Ohkawa S. Phase III study to assess long-term (52-week) safety and efficacy of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist, in Japanese patients with overactive bladder. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2017;9(1):38–45.

Khullar V, Amarenco G, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist, in patients with overactive bladder: results from a randomised European-Australian phase 3 trial. Eur Urol. 2013;63(2):283–95.

Herschorn S, Barkin J, Castro-Diaz D, et al. A phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre study to assess the efficacy and safety of the β3 adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, in patients with symptoms of overactive bladder. Urology. 2013;82(2):313–20.

Kuo HC, Lee KS, Na Y, et al. Results of a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo- and active-controlled, multicenter study of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist, in patients with overactive bladder in Asia. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(7):685–92.

Nitti VW, Auerbach S, Martin N, et al. Results of a randomized phase III trial of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol. 2013;189(4):1388–95.

Yamaguchi O, Marui E, Kakizaki H, et al. Phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron, 50 mg once daily, in Japanese patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2014;113(6):951–60.

Kim HW, Shin DG, Yoon SJ, et al. Mirabegron as a treatment for overactive bladder symptoms in men: efficacy and safety results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel comparison phase IV study (MIRACLE study) [abstract no. 273]. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(Suppl. 3):S247–9.

Nitti VW, Khullar V, van Kerrebroeck P, et al. Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: a prespecified pooled efficacy analysis and pooled safety analysis of three randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(7):619–32.

Chapple CR, Nitti VW, Khullar V, et al. Onset of action of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, in phase II and III clinical trials in patients with overactive bladder. World J Urol. 2014;32(6):1565–72.

Chapple C, Khullar V, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder by severity of incontinence at baseline: a post hoc analysis of pooled data from three randomised phase 3 trials. Eur Urol. 2015;67(1):11–4.

Khullar V, Amarenco G, Angulo JC, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron in a phase III trial in patients with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(8):987–94.

Castro-Diaz D, Chapple CR, Hakimi Z, et al. The effect of mirabegron on patient-related outcomes in patients with overactive bladder: the results of post hoc correlation and responder analyses using pooled data from three randomized phase III trials. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1719–27.

Khullar V, Cambronero J, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy of mirabegron in patients with and without prior antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a post hoc analysis of a randomized European-Australian phase 3 trial. BMC Urol. 2013;13(45):1–9.

Wagg A, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron for the treatment of symptoms of overactive bladder in older patients. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):666–75.

Tubaro A, Batista JE, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy and safety of daily mirabegron 50 mg in male patients with overactive bladder: a critical analysis of five phase III studies. Ther Adv Urol. 2017;9(6):137–54.

Nozawa Y, Kato D, Tabuchi H, et al. Safety and effectiveness of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder in a real-world clinical setting: a Japanese post-marketing study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12148.

Kato D, Tabuchi H, Uno S. Safety, efficacy, and persistence of long-term mirabegron treatment for overactive bladder in the daily clinical setting: interim (1-year) report from a Japanese post-marketing surveillance study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12188.

Yoshida M, Nozawa Y, Kato D, et al. Safety and effectiveness of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder aged ≥ 75 years: analysis of a Japanese post-marketing study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12190.

Kato D, Uno S, Van Schyndle J, et al. Persistence and adherence to overactive bladder medications in Japan: a large nationwide real-world analysis. Int J Urol. 2017;24(10):757–64.

Wagg A, Franks B, Ramos B, et al. Persistence and adherence with the new β3 receptor agonist, mirabegron, versus antimuscarinics in overactive bladder: early experience in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9(9–10):343–50.

Sussman D, Yehoshua A, Kowalski J, et al. Adherence and persistence of mirabegron and anticholinergic therapies in patients with overactive bladder: a real-world claims data analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12824.

Chapple CR, Nazir J, Hakimi Z, et al. Persistence and adherence with mirabegron versus antimuscarinic agents in patients with overactive bladder: a retrospective observational study in UK clinical practice. Eur Urol. 2017;72(3):389–99.

Astellas Pharma Ltd. Mirabegron (Betmiga)—new recommendations about the risk of increase in blood pressure [media release]. Sep 2015. http://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk.

Corcos J, Przydacz M, Campeau L, et al. CUA guideline on adult overactive bladder. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(5):E142–73.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary incontinence in women: management. Clinical guideline. 2013. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg171. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Kim TH, Lee KS. Persistence and compliance with medication management in the treatment of overactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol. 2016;57(2):84–93.

Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int. 2010;105(9):1276–82.

Sharaf AA, Hashim H. Profile of mirabegron in the treatment of overactive bladder: place in therapy. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2017;11:463–7.

Wallace KM, Drake MJ. Overactive bladder. F1000Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7131.1. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Athanasopoulos A, Giannitsas K. An overview of the clinical use of antimuscarinics in the treatment of overactive bladder. Adv Urol. 2011;2011:820816.

Andersson KE, Sarawate C, Kahler KH, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity, heart rates and use of antimuscarinics in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2010;106(2):268–74.

Rosa GM, Ferrero S, Nitti VW, et al. Cardiovascular safety of β3-adrenoceptor agonists for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder syndrome. Eur Urol. 2016;69(2):311–23.

Chapple CR, Siddiqui E. Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: a review of efficacy, safety and tolerability with a focus on male, elderly and antimuscarinic poor-responder populations, and patients with OAB in Asia. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(2):131–51.

Leonard CE, Reichman ME, Toh D, et al. Mini-Sentinel Prospective Surveillance Plan: prospective routine observational monitoring of mirabegron. 2016. http://www.sentinelinitiative.org. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Simeone JC, Nordstrom BL, Appenteng K, et al. Replication of Mini-Sentinel study assessing mirabegron and cardiovascular risk in non-Mini-Sentinel databases. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2018;5(1):25–34.

Kakizaki H, Lee KS, Yamamoto O, et al. Efficacy and safety of add-on mirabegron vs. placebo to tamsulosin in men with overactive bladder symptoms (MATCH study) [abstract no. LBA13]. J Urol. 2018;199(4S Suppl.):e988.

Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol. 2014;65(4):755–65.

European Association of Urology. Guidelines on urinary incontinence. 2015. https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/20-Urinary-Incontinence_LR.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2018.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mirabegron for treating symptoms of overactive bladder. Technology appraisal guidance. 2013. http://www.nice.org.uk. Accessed 18 May 2018.

Nazir J, Berling M, McCrea C, et al. Economic impact of mirabegron versus antimuscarinics for the treatment of overactive bladder in the UK. Pharmacoecon Open. 2017;1(1):25–36.

Nazir J, Maman K, Neine ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mirabegron compared with antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of adults with overactive bladder in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2015;18(6):783–90.

Aballea S, Maman K, Thokagevistk K, et al. Cost effectiveness of mirabegron compared with tolterodine extended release for the treatment of adults with overactive bladder in the United Kingdom. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35(2):83–93.

Angulo JC, Sanchez-Ballester F, Peral C, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of fesoterodine compared to mirabegron in first-line therapy setting for overactive bladder with urge urinary incontinence, from the Spanish National Health System perspective. Actas Urol Esp. 2016;40(8):513–22.

Acknowledgements

During the peer review process, the manufacturer of mirabegron was also offered the opportunity to review this article. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Conflict of interest

Emma D. Deeks is a salaried employee of Adis/Springer, is responsible for the article content and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional information

The manuscript was reviewed by: K. E. Andersson, Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA; H. Kuo, Department of Urology, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital and Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan; E. Sacco, Department of Urology, Agostino Gemelli Hospital, Catholic University Medical School, Rome, Italy; A. Wagg, Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deeks, E.D. Mirabegron: A Review in Overactive Bladder Syndrome. Drugs 78, 833–844 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0924-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0924-4