Abstract

Negative symptoms (such as amotivation and diminished expression) associated with schizophrenia are a major health concern. Adequate treatment would mean important progress with respect to quality of life and participation in society. Distinguishing primary from secondary negative symptoms may inform treatment options. Primary negative symptoms are part of schizophrenia. Well-known sources of secondary negative symptoms are psychotic symptoms, disorganisation, anxiety, depression, chronic abuse of illicit drugs and alcohol, an overly high dosage of antipsychotic medication, social deprivation, lack of stimulation and hospitalisation. We present an overview of reviews and meta-analyses of double-blind, controlled randomised trials, in which the efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for negative symptoms was assessed. Unfortunately, there have been very few clinical trials focusing on primary negative symptoms and selecting chronically ill patients with predominant persistent negative symptoms. An important limitation in many of these studies is the failure to adequately control for potential sources of secondary negative symptoms. At present, there is no convincing evidence regarding efficacy for any treatment of predominant persistent primary negative symptoms. However, for several interventions there is short-term evidence of efficacy for negative symptoms. This evidence has mainly been obtained from studies in chronically ill patients with residual symptoms and studies with a heterogeneous study population of patients in both the acute and chronic phase. Unfortunately, reliable information regarding the distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms is lacking. Currently, early treatment of psychosis, add-on therapy with aripiprazole, antidepressants or topiramate, music therapy and exercise have been found to be useful for unspecified negative symptoms. These interventions can be considered carefully in a shared decision-making process with patients, and are promising enough to be examined in large, well-designed long-term studies focusing on primary negative symptoms. Future research should be aimed at potential therapeutic interventions for primary negative symptoms since there is a lack of research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Available research data on treatments for primary negative symptoms are scarce and limited by the failure to control for sources of secondary negative symptoms. |

Interventions for negative symptoms have been investigated mainly in chronically ill patients with residual symptoms and heterogeneous study populations (acute and chronic phase) without distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms, and to a lesser extent in acutely ill patients with specific reference to secondary negative symptoms. |

There is no standard treatment for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. |

Meta-analyses and reviews provide no consistent evidence of the superior efficacy of any particular intervention in patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia. |

Early treatment of psychosis, add-on therapy with aripiprazole, antidepressants or topiramate, music therapy and exercise seem useful and viable interventions to reduce the severity of unspecified negative symptoms, and can be considered. The beneficial effect of these interventions may be limited to secondary negative symptoms. |

1 Introduction

The lifetime prevalence estimate for schizophrenia is 0.4% [1]. Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder presenting with positive and negative symptoms, emotional dysregulation and cognitive disturbances. Antipsychotic drugs have a moderate beneficial effect on positive symptoms [2, 3]. Unfortunately, negative symptoms respond poorly to medication [4], while these symptoms mainly account for functional and social outcome in schizophrenia [5].

Primary negative symptoms are thought to be intrinsic to schizophrenia. By definition, negative symptoms mean the absence of normal behaviour. Two subdomains can be distinguished: (1) avolition, apathy, lack of energy, anhedonia and social withdrawal, and (2) expressive deficits, which include blunted affect and poverty of speech [6]. Negative symptoms are associated with neurocognitive impairments [7] involving olfaction, social cognition, global cognition and language [8].

Patients with prominent negative symptoms fail to respond to both internal and external stimuli. Apathy does not seem to be associated with reduced attention to novel stimuli, but with slowed information processing [9]. Avolition may result from aberrant reinforcement learning. Patients with prominent negative symptoms fail to recognize the relative value of different rewards [10]. Impaired reward processing results in a limited behavioural repertoire and failure to activate behaviour to accomplish goals. In addition to disruptions in anticipatory pleasure and reward learning, impaired effort-based decision-making and social motivation also contribute to negative symptoms [11].

Psychomotor poverty with a flattened affect and decrease in spontaneous movements contribute to the loss of expression of emotions [12]. It is possible that psychomotor slowing with a decreased processing speed underlies verbal working memory impairment, which may mediate the association between working memory span deficit and negative symptoms [13]. A correlation has been found between working memory and awareness of illness, which explains the association between negative symptoms and poorer insight [14].

In the first 5 years of schizophrenia, negative symptoms decrease or remain stable [15]. Evidence indicating that negative symptoms persist in the long term is inconsistent [15, 16], which may suggest that more improvement of negative symptoms can be achieved than previously assumed [16].

Secondary negative symptoms are caused by other symptoms or circumstances. Psychosis, disorganisation, anxiety and depression sometimes lead to behavioural inhibition for which adequate treatment of the underlying psychopathology is recommended with psychotherapy, antipsychotics or antidepressants [17]. Chronic abuse of illicit drugs and alcohol may cause an amotivational syndrome which shows a close resemblance to the negative syndrome in psychosis [18]. In such cases, motivational interviewing may help to reduce substance abuse. However, at present there is no compelling evidence to support this intervention [19,20,21,22]. There is some indication that training family members in motivational interviewing results in greater reduction of cannabis use in their relatives [23, 24]. Lack of stimulation, demoralisation with reduced self-esteem, social deprivation, and residence in an institution are psychosocial factors that may contribute significantly to secondary negative symptoms for which rehabilitation [25], social skills training, cognitive remediation, family interventions [26] and physical activity [27] are appropriate interventions. Higher dosage of antipsychotics, and higher dopamine D2-receptor blockade have been hypothesised to cause iatrogenic negative symptoms. The impact of excessively high dopamine D2-receptor antagonism on subjective wellbeing has been found repeatedly [28,29,30,31]. In particular, patients complain of feeling numb, having diminished thoughts, amotivation and loss of hedonia. Therefore, too high a dosage of antipsychotic medication is thought to contribute to secondary negative symptoms. Unfortunately, despite increased use of lower dosage and/or second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) the prevalence of neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism with resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, loss of postural reflexes, flexed posture and motor blocking (freezing) is still substantial [32, 33]. Finally, premorbid personality dimensions, such as the schizoid dimension and, to a lesser extent, schizotypical and passive-dependent dimensions are non-specific risk factors for the expression of higher levels of negative symptomatology at the beginning of psychosis [34].

Estimates of healthcare resources utilisation and the costs associated with negative symptoms are high [35]. Although reduction of prominent negative symptoms may significantly improve functional and social outcome, relatively little research has been conducted in patients suffering predominantly from persistent primary negative symptoms. Primary negative symptoms, which are residual, chronic and relatively stable, are seldom the primary outcome in studies. In general, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) include acutely ill schizophrenia patients with primarily positive symptoms. However, study populations with predominantly positive symptoms are not appropriate for examining primary negative symptoms. Given this, and the fact that a better understanding of the pathogenesis of negative symptoms may help to intervene more effectively, research into the causes and treatment of negative symptoms is a high priority [36].

We examined the recent evidence supporting interventions for negative symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Our aim was to provide a comprehensive overview of treatments for primary negative symptoms, but unfortunately it proved impossible to achieve this aim (see Sect. 2.1 for further information). We briefly addressed the supposed explanation of action of these pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. We also aimed to explore whether pharmacological treatment options for negative symptoms are different in schizophrenia patients receiving non-clozapine antipsychotics compared to patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) receiving clozapine.

In this review, we will address the following topics: early intervention; low dosage of antipsychotics; pharmacological monotherapy; add-on therapy with dopaminergic medication; add-on therapy with serotonergic or noradrenergic medication; add-on therapy with glutamatergic medication; add-on therapy with cholinesterase inhibitors; add-on therapy with anti-inflammatory agents; add-on therapy with antioxidants; add-on therapy with hormone treatment; non-pharmacological treatments.

2 Methodological Considerations

2.1 Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We conducted a literature search of the PubMed database and the Cochrane Library (latest issue), limited to publications in the past decade up to 12/05/2017, concerning negative symptoms in schizophrenia, evidence supporting specific pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for these symptoms and the mechanism of action of the interventions. We limited our search to meta analyses and reviews, in order to increase the statistical power for group comparisons and to overcome the limitation of the small sample sizes used in several RCTs.

In an initial explorative search, we focused on interventions for primary negative symptoms, using the following terms: ‘primary negative symptoms’, ‘schizophrenia’ and ‘meta-analysis.’ When this first search for effective interventions for primary negative symptoms failed to reveal sufficient hits that were relevant to clinical practice, we imposed minimum constraints on our eligibility criteria. We selected meta-analytic comparisons between first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and SGAs, and between clozapine and FGAs and SGAs, and reviews and meta-analyses of double-blind RCTs, which targeted either primary negative symptoms in patients with predominant persistent negative symptoms or negative symptoms as primary or secondary outcome in acutely ill patients or chronically ill patients stable on medication with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Keywords used in the search process of the PubMed database included ‘negative symptoms’, ’schizophrenia’, ‘meta-analysis’ and ‘review’. A total of 147 hits were returned from PubMed. In addition, an equivalent search of the Cochrane Library was made, using the keywords ‘negative symptoms’ and ‘schizophrenia’. A total of 47 hits were returned from the Cochrane database. Relevant cross-references and related articles displayed in PubMed website pages were also screened and added to the common pool if found to be appropriate. After examining titles, abstracts and related articles, we selected relevant reviews and meta-analyses.

Reviews and meta-analyses on single medications were excluded, except when a specific medication was considered relevant and would not otherwise have been covered. Research on the efficacy of clozapine and amisulpride was specifically included, because of the unique receptor-binding profile of these antipsychotic medications. Clozapine has a distinct receptor-binding profile with a wide range of receptor affinities, including affinity to D4, D2, 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, α1, α2, acetylcholine, histamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate receptors [37]. The superior efficacy of clozapine is hypothesised to be caused by inverse 5-HT2A-receptor agonism and D4-receptor antagonism [37, 38]. Through antagonism of D4 receptors, clozapine acts as a glutamate agonist and through GABA the signal-to-noise ratio also improves in the prefrontal cortex [39]. However, the exact mechanism of clozapine is still unknown. Amisulpride may exert its efficacy for negative symptoms through a unique binding profile with a preferable affinity for D3 receptors, which are concentrated in limbic and cortical areas [40]. Moreover, at low doses, amisulpride preferentially blocks presynaptic dopaminergic auto-receptors, increasing dopaminergic transmission in the mesolimbic system and decreasing subcortical synthesis and the release of dopamine.

Articles without randomisation or control group and single-blind pharmacological studies were not included in the current review. Studies comparing two drugs in the absence of a placebo group were not included, because at present there is no evidence to assure that the active-control would have shown superior efficacy for negative symptoms over placebo, had a placebo group been included in the study. Moreover, if one drug is not found to be superior to a second, no conclusion can be drawn regarding the efficacy of either. Unpublished articles were also not included. There were no language restrictions. The diagram illustrates the process of review and exclusion of studies (see Fig. 1).

2.2 Outcome Measures

The articles included were heterogeneous, covering a wide range of interventions. The most important characteristics and findings of individual reviews and meta-analyses are described, including study design, inclusion criteria, description of the included population, comparisons and main results (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25). There are few studies focusing on primary negative symptoms, which included chronically ill patients with predominant and persistent negative symptoms. The studies of chronically ill patients failed to distinguish between primary negative symptoms and unresponsive secondary negative symptoms. In studies with a heterogeneous population of patients in both the acute phase and residual phase of their illness, reliable information regarding the distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms was again not available. In acutely ill patients, negative symptoms were characterized as secondary negative symptoms.

The limitations are assessed by reporting the between-study heterogeneity and whether included reviews and meta-analyses conducted sensitivity analyses to assess potential influences of any one single study on the pooled effect size. Bold results indicate statistical significance. Funding of included reviews and meta-analyses was reported as none, independent or pharmaceutical industry. The methodological quality of included reviews and meta-analyses was assessed using the validated AMSTAR (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews) tool [41, 42], which characterises quality at three levels: 0–3 is low quality, 4–7 is medium quality and 8–11 is high quality [43].

3 Early Intervention

Early detection and treatment of psychosis may improve primary negative symptoms. An early age of onset in children and adolescents, and an insidious symptom onset, predict a more serious negative syndrome [44,45,46]. However, negative symptoms are more difficult to detect in patients with a non-acute mode onset. Primary negative symptoms contribute to a delay in diagnosis, resulting in a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) compared with patients with an acute mode onset [45]. A meta-analysis of 28 studies (n = 3339) showed that a shorter DUP is associated with less severe negative symptoms (without distinguishing between primary and secondary negative symptoms) at short-term (1–2 years) and long-term (5–8 years) follow-up [47]. Improvement of negative symptoms was substantially greater in patients with a DUP shorter than 9 months. Early intervention is important, because a short DUP appears to be a predictor of short-term symptom and functional outcomes, based on the results of a meta-analysis of 43 RCTs of first-episode patients [48]. A meta-analysis of 33 RCTs revealed that a short DUP also predicts long-term recovery and functional remission [49]. The role of DUP in functional outcome appears to be mediated largely by primary negative symptoms [50]. Screening and ultra-high-risk (UHR) assessment of help-seeking individuals using the Comprehensive Assessment of at Risk Mental States (CAARMS) may enhance early detection of psychosis and shorten the DUP [51]. However, a long DUP may not be causally related to outcome in severely ill patients with poor insight [14], who often do not seek help. It may be that long DUP is a marker of a more severe form of schizophrenia with more substantial and persistent primary negative symptoms.

Furthermore, more severe negative symptoms are associated with less perceived social support, less friend support and higher levels of loneliness in young adults at UHR for psychosis [52]. Therefore, early interventions should also focus on increasing social networks in the prodromal phase, which may act as a protective factor against further development of secondary negative symptoms.

4 Low Dosage of Antipsychotics

The striatal, temporal and insular regions are involved in the control of motivation and reward. Occupancy of D2 receptors in these specific regions by antipsychotic medication appears to influence subjective experiences [31]. D2-receptor occupancy by antipsychotics of above 70% is related to negative subjective experience, more severe negative symptoms and depression [28,29,30].

However, antipsychotics in a relatively low dose do not seem to cause or worsen amotivation, which is an important feature of primary negative symptoms. In a recent prospective RCT (n = 520) motivational deficits and social amotivation were not found to be related to chronic antipsychotic treatment (olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone) in a dose-dependent manner [53]. Moreover, in 121 patients who were antipsychotic-free at baseline no significant changes in motivational deficits and social amotivation were found following 6 months of antipsychotic treatment. It is important to realise that the doses used in this study were in the relatively low range.

In conclusion, early intervention with a relatively low dosage of antipsychotic medication and dose reduction in patients with stable chronic schizophrenia may prevent or reduce secondary negative symptoms.

5 Pharmacological Monotherapy

5.1 Antipsychotic Medication

While FGAs mainly block the D2 receptor and improve—probably indirectly—only those negative symptoms that are secondary to positive and depressive symptoms, the receptor-binding profile of most SGAs extends beyond D2-receptor antagonism. Except for amisulpride, which is a pure D2- and D3-receptor antagonist [40], most SGAs also bind to serotonin, glutamate, histamine, α-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors [54]. The combination of D2-receptor blockade and inhibition of serotonin 5-HT2 receptors increases dopamine release in the frontal lobe, which may explain why SGAs could be superior to FGAs with regard to improvement in primary negative symptoms [55].

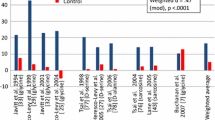

However, evidence on the efficacy of SGAs for negative symptoms is disappointing, based on medium to high-quality meta-analyses with significant heterogeneity across the included studies (see Tables 1, 2). A meta-analysis of—mainly short-term—RCTs evaluating the efficacy of nine SGAs compared to placebo found a small effect size (ES) for improvement of secondary negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients during an acute episode with predominant positive symptoms [2]. Although SGAs were found to be efficacious for negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) in a meta-analysis of 38 RCTs, no evidence was found that SGAs are superior to FGAs, since a trend towards superior efficacy of FGAs was based on an analysis of a small number (10) of RCTs [4]. A network meta-analysis on the efficacy of two FGAs and six SGAs in patients with early-onset schizophrenia (EOS, age of onset before 18 years) showed a positive trend towards reducing negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) compared with placebo [56]. Comparisons between these antipsychotics did not yield significant differences. A more recent network meta-analysis on the efficacy of one FGA and seven SGAs used for the acute treatment of EOS, found a superior efficacy of aripiprazole, asenapine, risperidone, olanzapine and molindone for secondary negative symptoms over placebo [57].

The results of medium-quality meta-analytic comparisons between SGAs versus FGAs without distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms demonstrate no consistent superiority of SGAs over FGAs. Heterogeneity between primary studies proved large and when superiority was found, the differences were small (see Table 2). A meta-analysis comparing nine SGAs with FGAs in acutely ill schizophrenia patients found that olanzapine, amisulpride, clozapine and risperidone were marginally more efficacious than FGAs in treating negative symptoms [3]. Non-equivalent dosing of SGAs versus FGAs confounds these findings. In another meta-analysis in first-episode schizophrenia disorders SGAs showed superior efficacy over FGAs [58]. However, this small ES disappeared and no significant difference was found between SGAs and FGAs after exclusion of industry-sponsored studies on SGAs (seven RCTs, n = 1430, p = 0.001) and analysis of independently funded studies (four RCTs, n = 501, p = 0.72).

Comparisons between different antipsychotics within a class revealed significant heterogeneity levels across the included studies and did not show that any single antipsychotic was superior for the treatment of negative symptoms (see Table 3). A medium-quality meta-analysis on the efficacy of the nine SGAs mentioned previously in a selection of patients with predominantly positive symptoms found insufficient evidence to prove any single SGA superior to any other for the treatment of secondary negative symptoms, with the exception of two small studies favouring quetiapine over clozapine [59]. A recent high-quality network meta-analysis compared the efficacy of nine antipsychotics in TRS [60]. For negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction), olanzapine was found to be superior to clozapine, risperidone, haloperidol, chlorpromazine and sertindole. Ziprasidone was more effective for negative symptoms than chlorpromazine and sertindole. These results should be interpreted with caution since the data on ziprasidone, fluphenazine, quetiapine, chlorpromazine and sertindole are limited.

While clozapine is the standard treatment for patients with TRS [61, 62], the superior efficacy of clozapine relative to other antipsychotic medication seems not to apply to negative symptoms [63]. Three Cochrane reviews compared the efficacy of clozapine with that of other antipsychotics in improving negative symptoms (without distinguishing between primary and secondary negative symptoms) in patients suffering from a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, most of whom were treatment-resistant (see Table 4). An early Cochrane review comparing short-term treatment with clozapine and FGAs in schizophrenia spectrum disorders found a significantly greater reduction of negative symptoms in clozapine-treated patients, but there was a substantial degree of heterogeneity between studies [64]. A Cochrane review comparing clozapine and SGAs found that clozapine was not more efficacious for negative symptoms than olanzapine or risperidone [65]. In a recent Cochrane review comparing combinations of clozapine with various other antipsychotics in TRS, negative symptoms were assessed in only one RCT, which found they did not improve significantly [66].

Findings of meta-analyses comparing clozapine with individual antipsychotics in TRS are inconsistent, and primary negative symptoms were not distinguished from secondary negative symptoms (see Table 5). A medium-quality meta-analysis showed superior efficacy of clozapine over olanzapine for negative symptoms (trial duration 8–28 weeks) [67]. A more recent medium-quality meta-analysis comparing clozapine with two FGAs and four SGAs in TRS found a superior short-term effect of clozapine for negative symptoms. The effect was no longer superior after a treatment duration of 3 months or more [68]. This discrepancy may be confounded by pharmaceutical industry funding of included studies and by the significantly lower doses of clozapine compared with those of control group medication, which may have biased the data against clozapine. In a recent high-quality network, meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of FGAs and SGAs, olanzapine was found to be significantly more efficacious for negative symptoms than clozapine in TRS [60]. Clozapine did not substantially differ from risperidone, haloperidol, ziprasidone, fluphenazine, quetiapine, chlorpromazine or sertindole. However, evidence on these last five antipsychotics is scarce, and blinded RCTs for the comparison of clozapine with other SGAs are limited. Moreover, clozapine plasma concentrations were not examined in most studies included in this meta-analysis and the clozapine titration speed was high. The sedative effects of clozapine may therefore explain why clozapine showed no superior efficacy over other antipsychotics.

There are few studies involving schizophrenia patients with prominent and persistent negative symptoms. Most of these studies have focused on the efficacy of low doses of amisulpride. A medium-quality meta-analysis comparing amisulpride with SGAs in acutely ill patients with predominant positive symptoms revealed a slight superior efficacy of amisulpride for secondary negative symptom improvement (see Table 6) [69]. In the same meta-analysis, superior efficacy of low-dose amisulpride (treatment duration 6–24 weeks) was found for primary negative symptoms over placebo in patients suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorders with predominant and persistent negative symptoms [69]. However, potential sources of secondary negative symptoms were not assessed, which may have confounded the effect on primary negative symptoms.

5.2 Metabotropic Glutamate 2/3 (mGluR 2/3) Receptor Agonists

Pomaglumetad methionil is a potent and highly selective mGluR 2/3 receptor agonist [70]. A beneficial effect on negative symptoms may arise from activation of these mGlu2 and mGlu3 receptors, which are found in high levels in the limbic system. Due to the inhibition of presynaptic glutamate release and modulation of synaptic plasticity, mGluR 2/3 agonists may influence negative symptoms. Although three RCTs did not show superiority over placebo in patients with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia, a post hoc exploratory study of five RCTs found a beneficial effect of pomaglumetad methionil (40 mg twice daily) on secondary negative symptoms in specific subgroups: patients with a duration of illness shorter than 3 years and patients who had previously received antipsychotic medication with predominant D2-receptor antagonism and without 5-HT2A-receptor antagonist activity [71].

MGluR-positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) are efficacious in animal studies and are currently being tested in phase II studies [72]. Although functional selectivity of third-generation antipsychotics was considered a breakthrough in the treatment of schizophrenia, clinical expectations of success of mGluR agonists have not been met and the development of these ligands for schizophrenia has been discontinued.

6 Add-On Therapy with Dopaminergic Medication

6.1 Dopamine Antagonists

On theoretical grounds, it is unlikely that the addition of a second dopamine antagonist to a non-clozapine antipsychotic would improve negative symptoms. Nevertheless, a recent medium-quality meta-analysis comparing antipsychotic augmentation versus monotherapy, mainly in inpatients with schizophrenia, favoured antipsychotic augmentation treatment over monotherapy for negative symptom improvement (see Table 7) [73]. However, a significant degree of heterogeneity was found between the included studies, which did not distinguish primary from secondary negative symptoms, and this favourable effect was restricted to augmenting with the partial dopamine agonist aripiprazole.

An earlier medium-quality meta-analysis showed that a second antipsychotic as adjunctive treatment to clozapine significantly but weakly improved negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) in TRS after exclusion of one outlier study on pimozide (see Table 8) [74]. Risperidone and aripiprazole are the two antipsychotics that have been studied the most in combination with clozapine. While the results on risperidone showed no significant improvement of negative symptoms compared to placebo, two separate meta-analyses of three RCTs of aripiprazole (duration 8–24 weeks) showed a similar trend towards reducing negative symptoms [74, 75] (see Table 8). A recent high-quality meta-analysis of placebo-controlled and open-label RCTs on the efficacy of aripiprazole augmentation showed a significant effect on negative symptoms in patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder who were receiving clozapine or non-clozapine antipsychotics (see Table 8) [76]. Important limitations were the inclusion of low-quality RCTs, a high level of heterogeneity across the included studies and the failure to discriminate primary from secondary negative symptoms.

6.2 Dopamine Agonists

Psychostimulants such as modafinil and armodafinil block the dopamine transporter, resulting in increased dopamine levels in the synaptic cleft [77]. Although theoretically a dopamine agonist could worsen positive symptoms, a meta-analysis of the effects of modafinil or armodafinil as add-on therapy to antipsychotics (both clozapine and non-clozapine antipsychotics) revealed no significant change in positive symptoms compared to placebo [78]. A beneficial effect on negative symptoms was hypothesised based on the increase of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex [79] and the nucleus accumbens [80], and a dose-dependent regional increase of glutamate and decrease of GABA [77]. In a medium-quality meta-analysis on adjunctive modafinil or armodafinil, a small significant improvement of negative symptoms (without discrimination between primary and secondary symptoms) was found compared with placebo in schizophrenia patients after 8 weeks of treatment (see Table 9) [78]. In all but one RCT, patients were on a stable dose of antipsychotic medication for at least 4 weeks. However, after exclusion of one RCT in which participants were inpatients in the active phase of the illness [81], the beneficial effect on negative symptoms was no longer significant.

In a Cochrane review, evidence for efficacy of amphetamine for negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) was limited to a single small study in chronic inpatients (see Table 10) [82]. In a low-quality review of psychostimulant treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia, no reduction of primary negative symptoms was found in a single study after treatment with methylphenidate in patients suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorders with predominant negative symptoms (see Table 10) [83].

7 Add-On Therapy with Serotonergic or Noradrenergic Medication

7.1 Serotonergic Medication

A synergistic effect of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and an antipsychotic through modulation of the GABA-A receptor and its regulating system is hypothesised to improve negative symptoms [55].

Medium to high-quality meta-analyses of RCTs in mostly chronic schizophrenia patients revealed superior efficacy of serotonergic medication compared to placebo for negative symptom improvement (without discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms) (see Table 11). A medium-quality meta-analysis of add-on treatment with antidepressants included RCTs examining SSRIs, the 5-HT2-receptor antagonist ritanserin, the serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) trazodone, α2-receptor antagonists (mirtazapine and mianserin) and the noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor (NRI) reboxetine in chronic schizophrenia [84]. Antidepressants were found to moderately improve negative symptoms with a NNT (number needed to treat) of 10–15. A sub-analysis showed that ritanserin (NNT = 5), trazodone (NNT = 6) and fluoxetine (NNT = 11) were the most efficacious. However, due to the relatively small sample sizes of separate RCTs, it was not possible to determine the superiority of a single antidepressant.

A smaller ES was found for antidepressants in a high-quality meta-analysis of a range of different treatments for negative symptoms in patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [4]. A more recent medium-quality meta-analysis on the efficacy of adjunctive antidepressants for negative symptoms, also found a small beneficial effect on negative symptoms compared to placebo in patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (NNT = 9) [85]. SSRIs stood out as a class, with fluvoxamine and citalopram showing consistent efficacy for negative symptoms. A subanalysis of patients with predominant negative symptoms revealed a higher ES for primary negative symptoms, but secondary negative symptoms were not eliminated from this analysis.

While selective 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (5-HT3R-ANTs) are generally used for the treatment of patients with postoperative or chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, 5-HT3R-ANTs may exert efficacy for negative symptoms in schizophrenia through modulation of mesolimbic and mesocortical dopaminergic activity [86]. In a medium-quality meta-analysis on the short-term efficacy of 5-HT3R-ANTs (tropisetron, ondansetron and granisetron) (duration 10 days–12 weeks, median 8 weeks) this add-on therapy to haloperidol or risperidone was found to be especially beneficial for negative symptoms in schizophrenia with clinical stability [87]. However, a significant degree of heterogeneity was found between the included studies. Further research of 5-HT3R-ANTs add-on therapy is necessary to confirm these positive findings and investigate long-term effectiveness.

7.2 Alpha-2 Receptor Antagonists

A presynaptic α2-receptor antagonist combined with a D2-receptor antagonist may cause an efflux of dopamine in the frontal cortex [88]. Two meta-analyses with a significant degree of heterogeneity show evidence of the efficacy of α2-receptor antagonists for negative symptoms in mostly acutely ill schizophrenia patients (see Table 12). A low-quality meta-analysis showed a large significant improvement of negative symptoms (without discrimination between primary and secondary symptoms) compared to placebo after 4–8 weeks adjunctive treatment with mirtazapine or mianserin [89].

A high-quality meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of mirtazapine and mianserin as augmentation therapy found a similar ES for secondary negative symptoms, mostly in inpatients with schizophrenia [90]. Sub-analysis revealed that adjunctive mirtazapine was superior to placebo, while mianserin did not show significant change compared to placebo for negative symptoms.

Mirtazapine (6 of 7 studies) and mianserin (1 of 3 studies) showed efficacy for negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) in a low-quality review (no funding, AMSTAR = 1) of several different add-on antidepressants (SSRIs, duloxetine, imipramine, mianserin, mirtazapine, nefazodone, reboxetine, trazodone and bupropion) in schizophrenia [91]. A beneficial effect for negative symptoms was also found for SSRIs: fluvoxamine (2 of 2 studies), paroxetine (1 study) and fluoxetine (2 of 6 studies). Trazodone (2 of 3 studies) and duloxetine (1 study) also improved negative symptoms.

7.3 Noradrenalin Reuptake Inhibitors (NRIs)

Noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors increase dopaminergic activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and influence the noradrenergic reward pathway, which could theoretically result in improvement of negative symptoms [92]. However, a high-quality meta-analysis on the efficacy of NRI augmentation to antipsychotic medication demonstrated no superiority of NRI add-on therapy to placebo for negative symptoms (without discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms) in chronic schizophrenia (see Table 12) [93]. Subanalyses of atomoxetine and reboxetine showed no effect on negative symptoms.

7.4 Augmentation to Clozapine

While considerable research has been conducted concerning antidepressant medication as add-on therapy to non-clozapine antipsychotics, only one meta-analysis of four RCTs (n = 111) examined the effect of the specific combination of an antidepressant and clozapine (no funding, AMSTAR = 5) [74]. Antidepressants (fluoxetine, mirtazapine and duloxetine) added to clozapine treatment compared to placebo addition showed a positive trend with a large ES (Hedges’ g = 0.87, p = 0.062) for reduction of negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction). The heterogeneity of the included studies was high (I 2 = 80%).

8 Add-On Therapy with Glutamatergic Medication

8.1 Glutamate Antagonists

Pharmacological treatment that targets the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor is supposed to improve the balance of glutamate [94, 95, 96]. We have hypothesised that the negative symptoms and cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia could be prevented if dysregulation of the NMDA receptor is addressed shortly after the onset of symptoms [97]. Novel pharmacological strategies, which are expected to boost the NMDA receptor function, have been thoroughly investigated over the past decade.

Topiramate potentiates GABA-ergic neurotransmission and decreases the presynaptic release of glutamate through antagonism of postsynaptic kainate receptors and amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazole-4-proprionic acid (AMPA) receptors [97]. Research on topiramate augmentation to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia spectrum disorders is extensive with six meta-analyses, but heterogeneity across primary studies is substantial (see Table 13). Whereas topiramate augmentation to clozapine did not show significant efficacy for secondary negative symptoms in two early, medium-quality meta-analyses of short-term RCTs (duration 8–24 weeks) in acutely ill patients with TRS [98, 99], three more recent medium to high-quality meta-analyses consistently demonstrated the efficacy of adjunctive topiramate mostly in inpatients suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorders [100,101,102]. However, no distinction is made between primary and secondary negative symptoms.

Subgroup analyses in the most recent high-quality meta-analysis revealed that topiramate augmentation to clozapine may be more efficacious than topiramate augmentation to non-clozapine antipsychotics.

Lamotrigine is an antagonist of postsynaptic voltage-sensitive sodium channels [36]. Three medium-quality meta-analyses show inconsistent evidence of the efficacy of lamotrigine augmentation to clozapine for negative symptoms in TRS (with no distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms) [98, 99, 103] (see Table 14). While an early meta-analysis of short-term RCTs (10–24 weeks) found superior efficacy of lamotrigine augmentation to clozapine compared with placebo [103], another meta-analysis of the same five RCTs found no significant difference in negative symptom improvement between lamotrigine and placebo after exclusion of an outlier study [98]. In a more recent meta-analysis of six RCTs (duration 10–24 weeks) on adjunctive lamotrigine to clozapine, the effect of lamotrigine on negative symptoms was on a trend level after excluding two outlier studies [99].

Memantine is a voltage-dependent, non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist that binds with a higher affinity than magnesium [97]. The neuroprotective properties of memantine are based upon this higher affinity, which blocks the effects of excessive glutamate. Thus, memantine may increase the signal-to-noise ratio, improve neurotransmission and reduce neuronal oxidative stress and degenerative changes in patients with increased levels of glutamate in the brain, such as patients with schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s disease. A medium-quality meta-analysis on the augmentation of NMDA receptor antagonists to ongoing antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia showed superior efficacy to placebo for negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) [104, 105] (see Table 14). Evidence for memantine addition to non-clozapine antipsychotics is limited to three RCTs. If the single positive study (ES = 1.5, p < 0.001) by Rezaei et al. is regarded as an outlier [106], the trend towards a superior effect of memantine (20 mg) compared with placebo in non-clozapine antipsychotics disappears [97]. The combination of clozapine and memantine is assumed to cause up-regulation of the NMDA receptor, resulting in an improvement of plasticity and glutamatergic tone in the PFC. When the signal-to-noise ratio improves, negative symptoms will be reduced. In a small 12-week proof-of-concept study in patients with predominant persistent negative symptoms, an exceptionally large ES of 3.33 (p = 0.001) was found in the memantine group (n = 10) compared with the placebo group (n = 11) [107]. However, this beneficial effect on primary negative symptoms was confounded by a large improvement in positive symptoms (ES = 1.38, p = 0.007), while the confounding factor of depressive symptoms was not assessed. A more recent crossover RCT (n = 52) detected no significant difference in positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms between the memantine and placebo group and showed a small significant improvement in negative symptoms compared to placebo after 12 weeks of add-on therapy with memantine (ES = 0.29, p = 0.043) [108].

Amantadine is a weak, non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist [109]. Neuroprotective properties are related to both stimulation of the release of neurotrophic factors by astrocytes and inhibition of the release of inflammatory factors by activated microglial cells. The effect of amantadine (200 mg) on negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) was studied in only a single 6-week crossover study (n = 23), which showed no superiority to placebo for negative symptoms [standardised mean difference (SMD) = 0.17, p = 0.68] [110].

8.2 Glutamate Agonists

In a medium-quality meta-analysis on the efficacy of NMDA receptor agonists as add-on therapy to antipsychotics (both non-clozapine and clozapine) in treating negative, positive and overall symptoms in TRS, a small significant improvement of negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) was found compared to placebo (see Table 15) [111]. Subanalysis of specific NMDA receptor agonists showed significant beneficial effects of d-serine, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and sarcosine in combination with non-clozapine antipsychotics. Beneficial effects on negative symptoms of d-alanine combined with non-clozapine antipsychotics and d-cycloserine combined with clozapine in single RCTs should be interpreted with caution.

In a more recent medium-quality review and meta-analysis of short-term RCTs (duration 6–14 weeks), the combination of clozapine and an NMDA receptor agonist (glycine, d-serine, d-cycloserine or sarcosine) was found not to differ from placebo treatment as regards negative symptom improvement in TRS (without discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms) (see Table 15) [99].

Results of phase III trials of bitopertin, a non-competitive glycine transporter I (GlyT1) inhibitor, were disappointing, and adverse drug reactions and complex dose titration in individual patients hampered further clinical development [112]. Although the development and evaluation of new Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antipsychotics, inspired by the NMDA receptor hypofunction hypothesis, have cost a tremendous amount of research funding over the past two decades, this line of research has not produced clinically relevant results.

9 Add-On Therapy with Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine or galantamine) increase the intrasynaptic concentration of acetylcholine through inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase and therefore act as indirect cholinergic agonists at muscarinic and nicotinic receptors [113]. Galantamine also acts as a PAM at the α7 nicotinic receptor, which does not cause α7 receptor desensitisation [114]. Negative symptoms may be alleviated due to direct muscarinic effects (independent of dopamine) or through a modulatory effect on the dopaminergic system [113]. The findings of a medium-quality meta-analysis and a Cochrane review on the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors for negative symptoms (without discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms) are disappointing (see Table 16). In the meta-analysis on the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine) as adjunctive therapy in patients with schizophrenia, the effect on negative symptoms with a treatment duration varying from 8 to 24 was not significant [115]. A Cochrane review analysis of two RCTs on the efficacy of donepezil and rivastigmine for negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients favoured an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor over placebo [116]. However, the quality of these studies was poor, with few participants (n = 31) and a short study duration. The lack of efficacy found for pure cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil and rivastigmine) may have been due to cigarette smoking, which causes desensitisation of α7 nicotinic receptors. A combination of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and a PAM of the α7 receptor would therefore deserve further study [117].

10 Add-On Therapy with Anti-Inflammatory Agents

10.1 Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

The immune hypothesis predicts that anti-inflammatory agents such as acetylsalicylic acid and celecoxib may have beneficial effects on the severity of overall symptoms of schizophrenia [118]. The combination of NSAIDs and SGAs was investigated in three meta-analyses in chronic schizophrenia patients with an acute exacerbation and first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients (see Table 17) [119,120,121]. In an early, medium-quality meta-analysis on NSAID augmentation, a small but significant effect for negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) was found compared to placebo [119]. Adjunctive NSAIDs seem to hold little promise, since no significant differences were found compared to placebo for improvement of secondary negative symptoms in two more recent high-quality meta-analyses concerning NSAIDs (trial duration 5–16 weeks) [120, 121]. A subgroup analysis revealed selective superiority of celecoxib in first-episode schizophrenia for secondary negative symptom improvement [121]. Maybe the use of NSAIDs in schizophrenia should only be considered when inflammatory markers are identified in early stages of schizophrenia [122]. However, more research is needed.

10.2 N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

Apart from being an anti-inflammatory agent and antioxidant [123], NAC provides cysteine for glutathione synthesis and is a NMDA receptor modulator [97]. A medium-quality review performed on NAC (no funding, AMSTAR = 5) revealed that evidence for NAC in schizophrenia is limited to two RCTs [124]. Addition of NAC (2000 mg) (n = 69) to antipsychotics (45% on clozapine) in patients with chronic schizophrenia showed no significant differences compared to placebo (n = 71) in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) negative subscale after 8 weeks of treatment, but after 24 weeks, negative symptoms were significantly improved (SMD = 0.8, p = 0.018) in the adjunctive NAC group [125]. The study design failed to discriminate between primary and secondary negative symptoms. A post hoc analysis of clozapine-treated patients showed a different pattern with a small significant reduction of negative symptoms (d = 0.30) after 8 weeks of NAC treatment (n = 28) compared to placebo (n = 27) and no significant change after 24 weeks [126].

In an 8-week RCT (n = 46) on NAC (2000 mg) in addition to risperidone, NAC-treated patients with chronic schizophrenia and prominent negative symptoms showed significantly greater improvement of primary negative symptoms than the placebo group (p < 0.001) [127]. No significant changes in confounding factors such as positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms were detected, during the course of this trial.

10.3 Minocycline

The antibiotic minocycline has neuroprotective properties due to a NMDA receptor antagonistic and an anti-inflammatory effect (see Table 17) [128]. A high-quality meta-analysis with a mean study duration of 25 weeks (range 8–52) found superior efficacy of adjunctive minocycline compared with placebo, especially for negative symptoms [129]. However, primary negative symptoms were not distinguished from secondary negative symptoms in the heterogeneous study population of patients in both the acute phase and residual phase of their illness. Moreover, heterogeneity across included studies was substantial. Post hoc sensitivity analysis, with regard to antipsychotic class, revealed that larger ESs were found for minocycline as an add-on to risperidone compared to other antipsychotics.

11 Add-On Therapy with Antioxidants

Oxygen-free radicals may contribute to the pathogenesis of negative symptoms, including increased lipid peroxidation, fatty acids and alterations in blood levels of anti-oxidant enzymes [130]. Antioxidants which neutralise these free radicals and reduce oxidative stress may therefore have potential to reduce negative symptoms.

11.1 Ethyl Eicosapentaenoic Acid (E-EPA)

Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid increases glutathione availability, modulates the glutamate/glutamine cycle and promotes antioxidative defence mechanisms [131]. E-EPA add-on therapy (4 RCTs in the chronic phase of schizophrenia and 1 RCT in FEP patients) [132,133,134,135,136] and E-EPA monotherapy in FEP patients [132] did not differ from placebo with regard to negative symptom improvement (without discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms) after 12–16 weeks of treatment.

11.2 Extract of Ginkgo Biloba

Extract of ginkgo biloba has antioxidant [137] and vasoactive properties [138]. Early research findings on ginkgo biloba concerning efficacy for negative symptoms were inconsistent [139, 140] (see Table 18). A medium-quality meta-analysis of three double-blind RCTs, two single-blind RCTs and one open-label study (trial duration 8–16 weeks) found a moderate beneficial effect of extract of ginkgo biloba on negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenia and TRS [139]. A high-quality meta-analysis of three RCTs (two double-blind and one single-blind) found a non-significant improvement of negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenia after a treatment duration of 8–12 weeks [140]. However, a more recent large, high-quality meta-analysis of eight Chinese RCTs (duration 8–16 weeks) showed moderate superior efficacy of ginkgo biloba over placebo for primary negative symptoms of chronic schizophrenia [141]. Further study of ginkgo biloba is warranted, since this positive result may be limited to the Chinese population and confounding factors including positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms were not assessed.

12 Add-On Therapy with Hormone Treatment

12.1 Sex Hormone Treatment

The action of oestrogen receptors in the brain may be blunted in women and men with schizophrenia [142]. Evidence of the efficacy of sex hormone treatment for negative symptoms is limited to a medium-quality meta-analysis, a Cochrane review (see Table 19) and two single RCTs. A medium-quality meta-analysis of sex hormone treatment and oxytocin showed significant improvement in negative symptoms [143]. However, primary negative symptoms were not distinguished from secondary negative symptoms. A moderate degree of heterogeneity was found between the included studies. A small significant effect was demonstrated in both treatment with oestrogen in premenopausal women and treatment with the selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM) raloxifene in postmenopausal women. No significant effects were found for negative symptoms in sub-analyses of pregnenolone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), testosterone or oxytocin.

A crossover RCT comparing 6 weeks of treatment with raloxifene (120 mg, n = 40) with placebo (n = 39) in premenopausal women and men suffering from chronic schizophrenia showed significant improvement of attention/processing speed and attention [144]. However, because negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) were mild at baseline, there was not much room for improvement of negative symptoms in this study. In an 8-week RCT on the effect of raloxifene (120 mg) add-on therapy to risperidone in male chronic schizophrenia patients with residual negative symptoms (n = 46) minimal changes in positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms were detected and a large reduction of primary negative symptoms was found compared to placebo (d = 1.3, p < 0.001) [145]. At present, the evidence for raloxifene in both male and female schizophrenia patients is encouraging, but limited [146]. Further research is needed to examine efficacy and potential long-term side effects. Raloxifene seems a safer hormone treatment than oestrogens, which are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, thromboembolic disease, breast cancer, and endometrial cancer in long-term use [147]. A potential side effect of raloxifene is a small increase of the risk of venous thromboembolism, but there is no evidence that this SERM affects the uterus [148].

A Cochrane review revealed that evidence regarding DHEA was limited to one single study of chronic schizophrenia patients with prominent negative symptoms, which demonstrated no beneficial effect on primary negative symptoms treated with DHEA compared to placebo [149]. Although no significant difference in positive and depressive symptoms was found between DHEA and placebo groups, extrapyramidal symptoms were not assessed as a possible confounding factor.

A single placebo-controlled RCT showed moderate significant improvement in primary negative symptoms after 4 weeks of administration of testosterone (5 g of 1% gel) in 30 male chronic schizophrenics with residual negative symptoms (ES = 0.64, p = 0.001), while confounding factors including positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms did not change significantly [150]. Total and free testosterone were the only serum hormone levels that significantly increased. Therefore, conversion of testosterone into oestradiol [151] cannot explain this beneficial effect.

12.2 Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a neurohormone, which also acts as a neurotransmitter regulating social cognition, stress, learning and memory [152]. While a medium-quality and a high-quality meta-analysis found inconsistent evidence of improvement in negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) with intranasal oxytocin as add-on therapy to SGAs [153, 154], an updated high-quality multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis of eight RCTs in patients suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorders, mostly with prominent negative symptoms, revealed that oxytocin was not beneficial for treating primary negative symptoms (see Table 19) [155]. While no significant difference in positive symptoms between the oxytocin and placebo groups was found, other potential sources of secondary negative symptoms (depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms) were not assessed.

13 Non-Pharmacological Treatments

13.1 Physical Activity

While researchers have not unravelled the exact underlying mechanism of exercise, there is substantial evidence of the efficacy of physical activity for negative symptoms (see Table 20). Unfortunately, no distinction was made between primary negative symptoms and secondary negative symptoms. Early medium- to high-quality meta-analyses revealed no beneficial effect on negative symptoms in inpatients or outpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders treated with yoga compared with usual care [156], yoga compared with exercise (two RCTs, n = 102) [156] or exercise compared with usual care [157]. A substantial degree of heterogeneity was found across the included studies. In a Cochrane review on the efficacy of yoga compared to standard care showed a beneficial effect of yoga was based on a single small study, which included inpatients with schizophrenia [158]. However, a more recent high-quality meta-analysis on the effect of interventions involving approximately 90 min of moderate-to-vigorous exercise per week (range 75–120 min) found a small-to-moderate significant reduction of negative symptoms in patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [159]. Another high-quality meta-analysis including aerobic exercise (endurance training, cardiovascular exercises, treadmill walking), anaerobic exercise (muscle strength training) and yoga found that exercise was more efficacious for negative symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder than treatment as usual (TAU) [27]. Subanalyses revealed superiority of aerobic exercise and yoga above TAU with similar ESs for negative symptom improvement. There were insufficient studies to conduct a subanalysis of anaerobic exercise. A more recent medium-quality meta-analysis replicated a beneficial effect of yoga for negative symptoms in patients suffering from a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [160]. However, the heterogeneity between the included studies was substantial.

13.2 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Negative symptoms are associated with low self-esteem and negative beliefs such as low expectations regarding pleasure and success [161]. There is no convincing evidence of the efficacy of CBT for primary negative symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (see Table 21). Research on CBT for primary negative symptoms is confounded by the failure to control for sources of secondary negative symptoms. While early research data concerning efficacy of CBT for negative symptoms were inconsistent [162,163,164,165,166], a recent high-quality meta-analysis of 30 RCTs (n = 2312) failed to affirm a positive effect [167]. Subanalyses revealed no significant effect of CBT interventions in 28 RCTs with negative symptoms as a secondary outcome (Hedges’ g = 0.093, p = 0.130), nor in two RCTs with negative symptoms as the primary outcome in patients with prominent negative symptoms. However, this subanalysis of primary negative symptoms was not controlled for positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms. In a more recent, but smaller and medium-quality meta-analysis, a small beneficial effect of CBT on negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) was found, but there was substantial heterogeneity between the included studies [160].

13.3 Cognitive Remediation (CR)

Cognitive remediation may affect negative symptoms by influencing working memory, reward sensitivity and executive functions [11]. Moreover, CR may result in a self-esteem boost by challenging defeatist beliefs, avoidance behaviour and poor motivation. A high-quality meta-analysis on the efficacy of CR in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders revealed a small reduction of negative symptoms (without primary/secondary distinction) at post-therapy compared to TAU and active treatment [168] (see Table 22). This beneficial effect of CR was maintained at follow-up. Moreover, studies with more robust methodology [Clinical Trial Assessment Measure (CTAM) ≥65] showed a larger negative symptom reduction compared to studies with a CTAM score below 65. A medium-quality meta-analysis also found a small beneficial effect of neurocognitive therapy compared to standard care and active treatment in patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, but primary negative symptoms were not distinguished from secondary negative symptoms and a substantial level of heterogeneity across studies was an important limitation [160]. In conclusion, more research is needed to affirm a beneficial effect of CR in patients suffering from prominent negative symptoms.

13.4 Other Forms of Psychotherapy

For psychological interventions other than cognitive remediation, the mode of action is unclear and the evidence is based on single meta-analyses with high levels of heterogeneity across the primary studies, which failed to discriminate between primary and secondary negative symptoms and included patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (see Table 23). Based on a high-quality meta-analysis [4], compared with standard care, psychological treatments (cognitive behavioural therapy, cognitive rehabilitation and music therapy) provide significant benefit for negative symptoms in adults suffering from a schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Integrated psychological therapy (IPT) combines neurocognitive and social cognitive interventions with social skills and problem-solving approaches, which was found to be superior over placebo-attention conditions and standard care in a medium-quality meta-analysis [169].

For post-treatment mindfulness interventions, a moderately beneficial effect for negative symptoms was found compared to standard care, active treatment or no treatment in a medium-quality meta-analysis with moderate-to-high heterogeneity between primary studies [170]. At follow-up, the effect was no longer superior.

A medium-quality meta-analysis comparing skills-based training, occupational therapy and cognitive adaptation therapy with standard care and active treatment revealed a beneficial effect for negative symptoms of these interventions, which was largely driven by studies using TAU as a control [160].

A medium-quality meta-analysis of three studies with a marginally significant heterogeneity did not favour family-based interventions over standard care or active treatment [160].

Based on the findings of a Cochrane review and two medium- and high-quality meta-analyses of studies in patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, with substantial heterogeneity between the included studies, which did not discriminate between primary and secondary negative symptoms, music therapy is a promising intervention (see Table 24). Compared with standard care, placebo treatment or no treatment, music therapy proved to be efficacious for negative symptoms in a Cochrane review of four RCTs, which also showed a larger reduction in high-dose music therapy compared to low-dose music therapy [171]. A high-quality meta-analysis (nine RCTs and one non-RCT) on adjunct music therapy to standard treatment revealed a significant and large beneficial effect for negative symptom improvement compared with standard treatment alone [172]. In another smaller, medium-quality meta-analysis, music therapy compared to standard care was found to moderately improve negative symptoms [160].

13.5 Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)

High-frequency bilateral rTMS uses strong magnetic pulses and increases brain activity in the dorsolateral PFC and the medial frontal gyrus [173]. For rTMS evidence for negative symptom improvement is not convincing, based on the inconsistent findings of five meta-analyses comparing rTMS with sham stimulation (see Table 25). In an early, low-quality meta-analysis, rTMS did not differ from sham stimulation as regards negative symptom improvement in chronic and stable schizophrenia patients [174]. A more recent, medium-quality meta-analysis found low-to-moderate efficacy of rTMS for negative symptoms in a heterogeneous study population of patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [175], which prompted additional research [176]. While these two meta-analyses failed to distinguish primary from secondary negative symptoms [174, 175], confounding factors were not assessed in another medium-quality, larger meta-analysis with moderate heterogeneity across studies [177]. A moderate improvement of primary negative symptoms was found in schizophrenia patients with prominent negative symptoms [177]. The optimal treatment duration was at least three consecutive weeks. However, two more recent high- and medium-quality meta-analyses with significant heterogeneity between primary studies and no discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms did not affirm the potential of rTMS for the treatment of negative symptoms [4, 178].

14 Discussion

At present, there is little robust and consistent evidence to support interventions for primary negative symptoms [179,180,181,182,183,184,185]. Moreover, no known treatment ameliorates both primary and secondary negative symptoms to such an extent that clinically significant improvement is achieved as measured on the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-S) [4]. However, the evidence for several interventions found in studies that did not focus on primary negative symptoms is more favourable.

We recommend that for patients with moderate-to-severe primary negative symptoms, psychiatrists should consider several possible interventions that are supported by some evidence from meta-analytic research and are relevant to clinical practice. These potential treatment options are discussed below. However, these recommendations should be treated with caution and both the possible benefits and the risks—such as potential adverse effects—should be discussed in a shared decision-making process with the patient.

The first step towards preventing or improving primary negative symptoms is early identification and treatment of psychosis [47,48,49,50,51]. Since antipsychotic medication in higher doses may contribute to secondary negative symptoms, an important recommendation is to use the lowest possible dosage of antipsychotic medication to improve subjective experiences and prevent neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Furthermore, for every patient without sufficient physical activity, frequent exercise with aerobic training or yoga is recommended [27].

Secondary negative symptoms should be prevented or treated adequately. Interventions aimed at diminishing the causal conditions of secondary negative symptoms are thought to be helpful and clinically relevant in reducing these symptoms. If positive symptoms persist in the absence of dose-related side effects, the dosage of antipsychotic should be increased or a switch to a different antipsychotic is recommended. If depression is present, psychotherapy and/or antidepressants are appropriate interventions [17]. If chronic abuse of illicit drugs and alcohol is problematic, we suggest motivational interviewing to reduce substance abuse, although at present evidence of the efficacy of this intervention is scarce [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Family interventions can be especially helpful if desolation and demoralisation are prominent [26]. Rehabilitation reduces fear and anxiety, and improves self-image, self-esteem, the ability to cope with stress and willingness to establish interpersonal relationships [25]. Since prominent negative symptoms have a large impact on the social and professional life of schizophrenia patients, causing social withdrawal, loss of autonomy, less employment or even long-term hospitalisation, psychiatric rehabilitation and a hope-oriented approach may contribute in an important way to the treatment of secondary negative symptoms.

Although SGAs were considered to have more potential for treating both primary and secondary negative symptoms, evidence of clear benefits of SGAs versus FGAs remains inconclusive for unspecified negative symptoms [3, 4, 58]. There is also no solid evidence for the superiority of any single antipsychotic for negative symptom improvement (without primary/secondary distinction) [56, 59, 60]. No consistently greater benefits of clozapine versus other antipsychotic treatment for unspecified negative symptoms have been demonstrated either [60, 64,65,66,67,68].

Aripiprazole augmentation seems beneficial for negative symptoms (without discrimination between primary and secondary negative symptoms) and is well tolerated in both patients receiving non-clozapine antipsychotics and in clozapine-treated patients [73, 76]. Most studies on antidepressants failed to specify primary negative symptoms by eliminating confounding factors. Although some SSRIs have been found to have beneficial effects, in particular fluvoxamine and citalopram [84, 85, 91] and the α2-receptor antagonists mirtazapine and mianserin [89,90,91], recent clinical guidelines for persistent negative symptoms state that SSRI or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) add-on treatment should be used with caution, since the reporting of adverse events is poor and inconsistent across all studies on the efficacy of add-on treatment with these antidepressants for persistent negative symptoms. There was no difference between the groups with regard to neurological adverse events, and psychotic symptoms neither worsened nor improved with SSRI therapy. Obvious adverse reactions such as serotonergic and sexual side effects and suicidal ideation were mentioned in a few of the studies, but poorly reported. No mention was made in any of the studies of suicide or suicide attempts [186]. Despite this, we believe that adjunctive antidepressants may be considered, since no study has found positive symptoms worsening as a result of antidepressants. Among glutamate antagonists as add-on therapy to both non-clozapine and clozapine antipsychotics, the most robust evidence favours topiramate for negative symptom improvement (without primary/secondary distinction), good tolerability and the additional advantage of weight maintenance [100,101,102].

Music therapy seems a viable treatment option for unspecified negative symptoms, without any adverse effects. It requires further research in patients with prominent primary negative symptoms.

Our review of evidence gathered over the past decade reveals that most RCTs were short term, conducted in chronically ill patients or patients in both the acute phase and residual phase of their illness. Unfortunately, the data required to distinguish primary from secondary negative symptoms, such as information demonstrating a stable disease course prior to the start of the study and levels of positive, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms at baseline and endpoint, are not available. Fewer studies included patients at the time of an acute psychotic episode and therefore were more focused on secondary negative symptoms. Persistent primary negative symptoms were often not the primary outcome variable. Recent meta-analyses and subanalyses of RCTs in patients with predominant persistent negative symptoms did not adequately control for confounding factors and have only been conducted for amisulpride [69], methylphenidate [83], antidepressants [85], extract of ginkgo biloba [141], oxytocin [155], cognitive training (CgT) [167] and rTMS [177]. The finding of a slight advantage of amisulpride over other SGAs or placebo should therefore be interpreted with caution [69]. Single studies on the efficacy of memantine [108], NAC [127], raloxifene [145], DHEA [149] and testosterone [150] in chronic schizophrenia patients with residual negative symptoms controlled for confounding factors, with the exception of DHEA, found a beneficial effect on primary negative symptoms.

The methodological quality of the included reviews and meta-analyses is generally medium to high. There were independent sources of funding or no financial support in the included meta-analyses and reviews, except for one low-quality review on psychostimulants [83]. Comparative research of different pharmacological treatments is hampered by small sample sizes, non-equivalent dosages, a range of concomitant antipsychotic regimens, variable duration of treatment, the nature of the inclusion criteria and outcome measures used, and funding bias. There are few comparisons of augmentation strategies for clozapine and non-clozapine antipsychotics.

In future research, the scientific quality of primary studies included in reviews and meta-analyses should be documented more extensively and considerations of scientific quality should be made explicit when formulating conclusions. Future reviews and meta-analyses should also improve with regard to reporting excluded studies and conflict of interest for each of the included studies. A study duration of at least 6 months is recommended to reasonably anticipate a clinically relevant improvement in primary negative symptoms [183]. Long-term studies that focus on prominent primary negative symptoms in the non-acute phase and control for confounders such as positive symptoms, depressive symptoms, and extrapyramidal side effects should be conducted to increase evidence for interventions for primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The inclusion of patients suffering from schizophrenia and especially TRS in treatment studies may be hampered, not only by negative symptoms, but also by paranoia, cognitive impairments, impaired decisional capacity [187], compromised ability to appreciate risk information [188] and fear of experiencing adverse events [189]. In the future, long-term, prospective naturalistic studies on the efficacy of interventions in everyday practice may have more success in including such patients and may therefore yield clinically relevant evidence that is more generalisable than that gained in double-blind RCTs [190]. Moreover, a better understanding of the pathogenesis of negative symptoms may help to identify potential new treatment targets to develop more specific interventions for primary negative symptoms. Perhaps in the future we will be able to determine the specific pathogenesis of primary negative symptoms in individual patients using hormone levels, neuroimaging of dopamine synthesis, frontal glutamate levels and activation of microglial cells [191, 192]. Personalised medicine may be possible in which treatment targets the specific underlying mechanism in individual patients. Moreover, it is conceivable that certain interventions are efficacious in a particular phase of schizophrenia. Currently we lack evidence for such individualised and phase-specific interventions.

15 Conclusion

Negative symptoms remain an important treatment challenge. It is clear that we currently lack convincing evidence that patients with primary negative symptoms can be effectively treated with targeted interventions. There is also no consistent evidence indicating a preferential intervention to treat primary negative symptoms. However, there is evidence for modest short-term efficacy of several interventions in patients with unspecified negative symptoms. Potential side effects should be considered carefully in the shared decision-making process regarding medication. We urgently need more robust evidence. This review highlights the need for large, well-designed long-term studies.

References

McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi AO, et al. Age of onset and lifetime projected risk of psychotic experiences: cross-national data from the World Mental Health Survey. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:933–41.

Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, et al. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;4:429–47.

Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:31–41.

Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, et al. Treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of 168 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:892–9.

Ventura J, Subotnik KL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Negative symptoms and functioning during the first year after a recent onset of schizophrenia and 8 years later. Schizophr Res. 2015;161:407–13.

Millan MJ, Fone K, Steckler T, et al. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: clinical characteristics, pathophysiological substrates, experimental models and prospects for improved treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:645–92.

Hartmann-Riemer MN, Hager OM, Kirschner M, et al. The association of neurocognitive impairment with diminished expression and apathy in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;169:427–32.

Cohen AS, Saperstein AM, Gold JM, et al. Neuropsychology of the deficit syndrome: new data and meta-analysis of findings to date. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1201–12.

Roth RM, Koven NS, Pendergrass JC, et al. Apathy and the processing of novelty in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:232–8.

Gold JM, Waltz JA, Matveeva TM, et al. Negative symptoms and the failure to represent the expected reward value of actions: behavioral and computational modeling evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:129–38.

Reddy LF, Horan WP, Green MF. Motivational deficits and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: concepts and assessments. Curr Topics Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:357–73.

Walther S, Strik W. Motor symptoms and schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 2012;66:77–92.

Brébion G, Stephan-Otto C, Huerta-Ramos E, et al. Decreased processing speed might account for working memory span deficit in schizophrenia, and might mediate the associations between working memory span and clinical symptoms. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:473–8.

Pegoraro LF, Dantas CR, Banzato CE, et al. Correlation between insight dimensions and cognitive functions in patients with deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;147:91–4.

Heilbronner U, Samara M, Leucht S, et al. The longitudinal course of schizophrenia cross the lifespan: clinical, cognitive, and neurobiological aspects. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016;24:118–28.

Savill M, Banks C, Khanom H, et al. Do negative symptoms of schizophrenia change over time? A meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1613–27.