Abstract

Pixantrone (Pixuvri®) is an aza-anthracenedione with a novel mode of action that is conditionally approved in the EU for use as monotherapy in adult patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). In the randomized, open-label, multinational, phase 3 PIX301 trial in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL, the complete response (CR) plus unconfirmed CR (uCR) rate at the end of treatment (primary endpoint) was significantly higher with intravenous pixantrone monotherapy than with a single-agent comparator (vinorelbine, oxaliplatin, ifosfamide, etoposide, mitoxantrone or gemcitabine). Post hoc analysis also demonstrated a significantly higher CR/uCR rate in the subgroup of patients with centrally confirmed aggressive B-cell NHL who were receiving pixantrone versus a comparator agent as third- or fourth-line therapy. Pixantrone was generally well tolerated in PIX301, with a manageable adverse event profile. In conclusion, pixantrone is a useful option in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL. Further results examining the use of pixantrone in combination with rituximab in patients previously treated with rituximab-containing regimens are awaited with interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Aza-anthracenedione with a novel mode of action |

Associated with a higher CR/uCR rate than comparator agents in patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive NHL, including in patients with aggressive B-cell NHL receiving third- or fourth-line therapy |

Generally well tolerated with a manageable adverse event profile |

1 Introduction

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) comprises a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common NHL subtype and accounts for ≈75 % of all aggressive lymphomas [1, 2]. First-line therapy in patients with aggressive B-cell NHL usually comprises an anthracycline-based regimen in combination with rituximab [1]. However, the risk of cardiotoxicity increases as the cumulative anthracycline dose increases [3], limiting the repeated use of these agents in patients with relapsed or refractory disease [4].

The novel anthracenedione pixantrone (Pixuvri®) was developed to have a reduced risk of cardiotoxicity whilst maintaining efficacy [5]. Pixantrone is conditionally approved in the EU for use as monotherapy in adult patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL [6]. This narrative review discusses the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of pixantrone monotherapy in multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL, as well as summarizing its pharmacological properties. Pixantrone is administered intravenously in its salt form, pixantrone dimaleate; doses reported in this article refer to pixantrone in its base form (pixantrone dimaleate 85 mg equates to pixantrone 50 mg).

2 Pharmacodynamic Properties of Pixantrone

Pixantrone is an aza-anthracenedione that has a novel mode of action compared with other anthracenediones (e.g. mitoxantrone) and anthracyclines (e.g. doxorubicin) [5, 7]. The structure of pixantrone differs from that of mitoxantrone in that the hydroquinone moiety has been removed, a nitrogen heteratom has been inserted in the same ring and (ethylamino)-diethylamino side chains have been substituted for (hydroxyethylamino)-ethylamino side chains [8, 9]. Pixantrone directly alkylates DNA, forming stable DNA adducts and inducing DNA double-strand breaks, which prevents DNA replication, transcription and repair [5–7, 10, 11]. Pixantrone also appears to induce a latent type of DNA damage that impairs mitosis [12].

Iron-dependent oxygen free radical formation is thought to be at least partly responsible for the cardiotoxicity associated with anthracyclines [9, 11]. Unlike anthracyclines, pixantrone does not bind iron, meaning it has less potential to generate reactive oxygen species or form long-lasting alcohol metabolites [6, 8, 9, 11]. Ex vivo, the N-dealkylated metabolite of pixantrone inhibited the metabolism of residual doxorubicin to doxorubicinol; the long-term risk of cardiotoxicity is linked to the cardiac accumulation of doxorubicinol [9].

As well as oxidative damage, topoisomerase IIβ-mediated responses to DNA damage may contribute to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity [11]. Pixantrone is a relatively weak inhibitor of topoisomerase II compared with other anthracenediones and anthracyclines [6, 12]. Moreover, compared with mitoxantrone, pixantrone showed greater selectivity for inhibition of topoisomerase IIα versus topoisomerase IIβ [11].

In vitro, pixantrone demonstrated greater cytotoxicity in lymphoma and leukaemia cell lines than in solid tumour cell lines, and also showed antitumour activity in murine models of lymphoma and leukaemia [13]. Pixantrone had less cardiotoxic potential than mitoxantrone [13, 14] or doxorubicin [14, 15] in murine studies. For example, pixantrone induced minimal cardiac changes in mice, including in doxorubicin-pretreated mice with pre-existing cardiomyopathy [14].

3 Pharmacokinetic Properties of Pixantrone

Intravenous pixantrone 3–105 mg/m2 had linear pharmacokinetics [6, 16, 17]. Population pharmacokinetic analysis reported a median 28-day cycle exposure of 6320 ng · h/mL when three doses of pixantrone 50 mg/m2 were administered over a 4-week cycle [6]. Pixantrone had a volume of distribution of 25.8 L and was ≈50 % plasma protein bound [6].

Metabolism does not appear to be an important route of elimination for pixantrone [6]. Rather, biliary excretion of unchanged pixantrone may be the primary route of elimination. Data suggest a high hepatic extraction ratio for pixantrone, with hepatic uptake possibly mediated by the transporter OCT-1 and biliary excretion possibly mediated by the transporters P-gp and BCRP [6]. Plasma clearance of pixantrone was 72.7 L/h with renal excretion accounting for <10 % of the dose in the 24 h following administration [6, 16, 17]. Pixantrone had a mean terminal elimination half-life ranging from 14.5 to 44.8 h, with mean and median values of 23.3 and 21.2 h [6].

Although no formal drug-drug interaction studies have been conducted, no interactions between pixantrone and other agents (e.g. cytarabine, cisplatin, methylprednisolone) were reported in clinical studies [6, 18].

Possible mixed-type inhibition of CYP1A2 and CYP2C8 was seen with pixantrone in vitro [6]. Theoretically, coadministration of pixantrone may increase plasma concentrations of CYP1A2 substrates (e.g. theophylline, warfarin, amitriptyline, haloperidol, clozapine, ondansetron, propranolol). In particular, the EU summary of product characteristics (SmPC) recommends that theophylline concentrations be carefully monitored in the weeks following the start of pixantrone therapy, and that coagulation parameters (e.g. international normalized ratio) be monitored in patients receiving warfarin in the days following the start of pixantrone therapy. The EU SmPC also recommends caution (e.g. careful monitoring for adverse events) when coadministering pixantrone and CYP2C8 substrates (e.g. repaglinide, paclitaxel) [6].

In vitro, pixantrone was a substrate for the transporters P-gp, BCRP and OCT-1 [6]. Thus, inhibitors of these transporters (e.g. ciclosporin, tacrolimus, ritonavir, saquinavir, nelfinavir) have the potential to decrease the elimination of pixantrone, and the EU SmPC recommends that blood counts be closely monitored in patients coadministered these agents [6]. In addition, caution is recommended when pixantrone is continuously coadministered with inducers of efflux transporters (e.g. rifampicin, carbamazepine, glucocorticoids), as the systemic exposure of pixantrone may be decreased [6].

4 Therapeutic Efficacy of Pixantrone

Phase 1 dose-escalating studies of pixantrone monotherapy in solid tumours [16, 19] and relapsed or refractory NHL [17] established that its dose-limiting toxicity was neutropenia, and led to a regimen of intravenous pixantrone 50 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day cycle being selected for further development. Pixantrone monotherapy also demonstrated efficacy in a phase 2 study in patients with relapsed aggressive NHL [20].

The focus of this section is the randomized, open-label, multinational, phase 3 PIX301 trial, which examined the efficacy of pixantrone monotherapy in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL [21]. Patients were aged ≥18 years, had aggressive de novo or transformed NHL and had relapsed after at least two prior chemotherapy regimens, including at least one standard anthracycline-containing regimen with a response lasting ≥24 weeks. Patients also had to have a life expectancy of ≥3 months, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of ≤2, measurable disease and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≥50 %. If patients lived in a country where rituximab was available, they had to have received prior rituximab in order to be eligible for the study [21].

Patients received intravenous pixantrone 50 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day cycle for up to six cycles or the physician’s choice of a comparator agent (vinorelbine, oxaliplatin, ifosfamide, etoposide, mitoxantrone, gemcitabine or rituximab) administered according to a prespecified treatment regimen (see Table 1 for details of comparator agent regimens) [21]. The median number of cycles administered was four for pixantrone (median dose intensity of 55 mg/m2/week) and three for the comparator agent. Enrolment in PIX301 was closed early because of slow accrual (the planned sample size was 320 patients, whereas 140 patients were randomized between 12 October 2004 and 17 March 2008) [21].

In patients randomized to pixantrone or a comparator agent, median age at baseline was 60 and 58 years, the median duration of NHL was 32.0 and 31.6 months, the median number of previous chemotherapy regimens was 3.0 and 3.0, and the median previous doxorubicin dose equivalent was 292.9 and 315.5 mg/m2 [21]. Overall, 64 % of patients had an ECOG performance status of 1 or 2 at baseline; 76 % were Ann Arbor Stage III–IV; 27, 37 and 35 % had an International Prognostic Index (IPI) score of 0–1, 2 and ≥3, respectively; 57 % had refractory disease and 41 % had relapsed disease; 55 % had previously received rituximab; and 15 % had previously undergone stem cell transplantation. With regard to the NHL subtype (histologically confirmed on-site), 74 % of patients had DLBCL, 14 % had transformed indolent lymphoma, 7 % had peripheral T-cell lymphoma (not otherwise classified), 3 % had primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (null cell type) and 2 % had grade 3 follicular lymphoma [21].

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients with a complete response (CR) or an unconfirmed CR (uCR) at the end of treatment (based on International Working Group criteria [22]), as assessed by an independent assessment panel who were blinded to treatment assignment [21]. Efficacy was assessed in the intent-to-treat population [21].

Overall, the CR/uCR rate at the end of treatment was significantly higher in patients receiving pixantrone monotherapy than in patients receiving a comparator agent (Table 1) [21]. The CR rate and the overall response rate (ORR) at the end of treatment were also significantly higher with pixantrone than with a comparator agent, with no significant between-group difference in the uCR rate at the end of treatment (Table 1). Response rates at the end of the study and the median duration of CR/uCR are shown in Table 1 [21].

The median duration of progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly longer in patients receiving pixantrone than in those receiving a comparator agent, with no significant between-group difference in overall survival (OS) (Table 1) [21].

Post hoc analyses also examined response rates and PFS according to prior rituximab treatment and the number of prior chemotherapy regimens [21]. Among patients assigned to pixantrone who had previously received rituximab and two (n = 10), three (n = 15) or at least four (n = 13) chemotherapy regimens, the CR/uCR rate was 30.0, 20.0 and 7.7 %, respectively, and the ORR was 50.0, 40.0 and 7.7 %, respectively; the median PFS was 5.7 and 3.3 months with two and three prior chemotherapy regimens. Among patients assigned to a comparator agent who had previously received rituximab and two (n = 9), three (n = 16) or at least four (n = 14) chemotherapy regimens, the CR/uCR rate was 0, 6.3 and 21.4 %, respectively, and the ORR was 0, 18.8 and 28.6 %, respectively; the median PFS was 2.8 months with both two and three prior chemotherapy regimens. Among patients assigned to pixantrone who had not received prior rituximab and previously received two (n = 22), three (n = 9) or at least four (n = 1) chemotherapy regimens, the CR/uCR rate was 36.4, 22.2 and 0 %, respectively, and the ORR was 50.0, 44.4 and 100.0 %, respectively; the median PFS was 5.7 and 6.5 months with two and three prior chemotherapy regimens. Among patients assigned to a comparator agent who had not received prior rituximab and previously received two (n = 15) or three (n = 16) chemotherapy regimens, the CR/uCR rate was 6.7 and 0 %, the ORR was 13.3 and 6.3 %, and the median PFS was 1.9 and 3.4 months. Median PFS was not analysed in patients who had previously received at least four chemotherapy regimens because of insufficient patient numbers in the group with no prior rituximab therapy [21].

Pixantrone appeared more effective than the comparator agent independent of prior rituximab therapy, according to the results of another post hoc analysis in patients with histological confirmation by blinded centralized review of aggressive B-cell NHL [i.e. DLBCL (n = 82), transformed indolent lymphoma (n = 12) or grade 3 follicular lymphoma (n = 3)] [23]. A significantly (p < 0.05) higher CR/uCR rate (23.1 vs. 5.1 %), CR rate (17.9 vs. 0 %) and ORR (43.6 vs. 12.8 %) was seen in patients with centrally confirmed aggressive B-cell NHL who were receiving pixantrone (n = 39) versus a comparator agent (n = 39) as third- or fourth-line therapy, with or without prior rituximab. In patients with centrally confirmed aggressive B-cell NHL who had previously received rituximab and were receiving pixantrone (n = 20) or a comparator agent (n = 18) as third- or fourth-line therapy, the ORR was significantly higher with pixantrone than with a comparator agent (45.0 vs. 11.1 %; p = 0.033), with no significant between-group differences in the rate of CR/uCR (30.0 vs. 5.6 %) or in the median duration of PFS (5.4 vs. 2.8 months) or OS (7.5 vs. 5.4 months). In patients with centrally confirmed aggressive B-cell NHL who had not previously received rituximab and were receiving pixantrone (n = 19) or a comparator agent (n = 21) as third- or fourth-line therapy, no significant differences were seen between pixantrone and the comparator agent in terms of the CR/uCR rate (15.8 vs. 4.8 %), ORR (42.1 vs. 14.3 %) or the median duration of PFS (6.1 vs. 3.5 months) or OS (14.5 vs. 7.8 months). It should be noted that this post hoc analysis was not powered to test for treatment effects in these subgroups [23].

5 Safety and Tolerability of Pixantrone

Monotherapy with intravenous pixantrone was generally well tolerated in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL. In PIX301, adverse events occurred in 97 % of patients receiving pixantrone and in 91 % of patients receiving a comparator agent, with treatment-related adverse events occurring in 81 and 57 % of patients in the corresponding treatment groups [21]. Adverse events of any grade occurring in ≥10 % of patients in either treatment arm included neutropenia (50 % of pixantrone recipients vs. 24 % of comparator agent recipients), anaemia (31 vs. 33 %), leukopenia (25 vs. 10 %), pyrexia (24 vs. 24 %), asthenia (24 vs. 13 %), cough (22 vs. 4 %), thrombocytopenia (21 vs. 19 %), decreased LVEF (19 vs. 10 %), nausea (18 vs. 16 %), abdominal pain (16 vs. 10 %), peripheral oedema (15 vs. 6 %), fatigue (13 vs. 13 %), dyspnoea (13 vs. 13 %), alopecia (13 vs. 4 %), constipation (12 vs. 4 %), mucosal inflammation (12 vs. 3 %), skin discolouration (10 vs. 0 %), vomiting (7 vs. 15 %), diarrhoea (4 vs. 18 %) and progression of malignant neoplasms (1 vs. 13 %). Serious adverse events were reported in 51 % of patients receiving pixantrone and in 45 % of patients receiving a comparator agent [21].

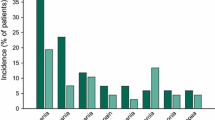

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 76 % of patients receiving pixantrone and in 52 % of patients receiving a comparator agent [21]. Neutropenia and leukopenia were the most commonly occurring grade 3 or 4 adverse events, occurring in numerically more patients receiving pixantrone versus a comparator agent (Fig. 1). The severity of neutropenia did not increase as the number of pixantrone cycles increased. Rather, neutropenia was usually transient, with the nadir reached on days 15–22 and recovery usually seen by day 28 when pixantrone was administered on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day cycle [6]. It should be noted that blood counts were monitored more frequently in pixantrone recipients than in comparator agent recipients during this trial [21].

Most frequent grade 3 or 4 adverse events in the PIX301 trial [21]. PIX301 included patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma who received intravenous pixantrone or a comparator agent (vinorelbine, oxaliplatin, ifosfamide, etoposide, mitoxantrone or gemcitabine)

Cardiac adverse events occurred in 35 % of patients receiving pixantrone and in 21 % of patients receiving a comparator agent [21]. Asymptomatic reduction in LVEF was the most commonly occurring cardiac adverse event; the median change from baseline in LVEF was −4 % in patients receiving pixantrone and 0 % in patients receiving a comparator agent [21]. Nine cardiac adverse events (all asymptomatic reductions in LVEF) were considered to be related to pixantrone [24]. There was no evidence of a cumulative, dose-related decline in LVEF in pixantrone recipients [21], and no demonstrable relationship between the cumulative pixantrone dose and the occurrence of symptomatic reductions in LVEF or congestive heart failure (CHF) [24]. It should be noted that five patients assigned to pixantrone had a history of CHF (n = 3) or continuing cardiomyopathy (n = 2), whereas no patient in the comparator agent arm had a history of CHF or continuing cardiomyopathy [21].

Death occurred within 30 days of the last dose of study drug in 10 patients (15 %) receiving pixantrone and 12 patients (18 %) receiving comparator agents, with 5 and 11 deaths in the corresponding treatment groups thought to be related to progressive disease; only one death (septic shock) was considered related to pixantrone treatment [21]. Three deaths considered related to treatment occurred >30 days after the last dose of pixantrone (acute CHF, myelodysplastic syndrome) or comparator agent (renal failure) [24].

6 Dosage and Administration of Pixantrone

Pixantrone is conditionally approved in the EU for use as monotherapy in adult patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL [6]. The benefit of pixantrone has not been established when used as fifth line or greater chemotherapy in patients refractory to last therapy [6].

The recommended dosage of intravenous pixantrone is 50 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day cycle for up to six cycles [6]. Haematological and non-haematological toxicity should be carefully monitored during the course of the treatment cycle (i.e. on days 8 and 15), and before initiation of a new cycle of treatment. Definitive recommendations for dose delay and/or modification, depending on the characteristics and/or severity of the adverse reactions, are provided in the EU SmPC [6].

The efficacy and safety of pixantrone have not been established in patients with renal or hepatic impairment [6]. Pixantrone should be used with caution in patients with renal impairment or mild or moderate hepatic impairment, and is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Additional contraindications include the use of pixantrone in patients with profound bone marrow suppression, and immunization with live virus vaccines in patients receiving pixantrone [6].

Local prescribing information should be consulted for more information concerning contraindications, special warnings and precautions and dosage adjustments related to pixantrone.

7 Place of Pixantrone in the Management of Relapsed or Refractory Aggressive NHL

An anthracycline-based regimen [usually rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP)] is considered standard first-line therapy in aggressive B-cell NHL [1, 25]. Second-line salvage therapy usually comprises a platinum-based regimen [such as rituximab plus ifosfamide, cisplatin and etoposide (R-ICE) or rituximab plus dexamethasone, cytarabine and cisplatin (R-DHAP)], followed by consolidation of the response with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in eligible patients [1, 4, 25]. However, there is a lack of consensus regarding third- and fourth-line treatment in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL [25, 26]. Indeed, treatment options are limited in this patient population, with the risk of long-term cardiotoxicity meaning that retreatment with anthracyclines is usually avoided [4].

Pixantrone was designed to maintain efficacy whilst reducing the risk of cardiotoxicity [5]. The PIX301 trial included patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL; approximately three-quarters of patients had DLBCL, meaning that the study population is representative of the majority of the target population [24]. Response rates were significantly higher and median PFS was significantly longer with pixantrone than with a comparator agent in this heavily pretreated population (Sect. 4). Although response rates appeared low with pixantrone in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL who had received at least four prior chemotherapy regimens, third- or fourth-line therapy with pixantrone demonstrated efficacy in patients with centrally confirmed aggressive B-cell NHL in post hoc analyses (Sect. 4).

Diminished response rates have been reported when salvage chemotherapy is administered following rituximab [27]. In post hoc analyses of PIX301, prior rituximab therapy appeared to have little impact on the ORR in pixantrone recipients who had received two or three prior chemotherapy regimens, and a benefit was seen with pixantrone versus the comparator agent regardless of prior rituximab exposure (Sect. 4) [21, 23].

Most patients being treated today in Europe for multiply relapsed or refractory B-cell NHL will have received prior rituximab [24]. However, PIX301 was started in 2004, before rituximab became the standard of care, and only 55 % of patients included in the trial had received prior rituximab [21]. Also, although the endpoint of uCR is now obsolete, it was considered an acceptable endpoint at the time that PIX301 was initiated [25]. It should also be noted that PIX301 was underpowered, as it did not recruit the planned number of patients and was terminated early [21].

Pixantrone was generally well tolerated with a manageable adverse event profile. Reversible myelosuppression (i.e. neutropenia, leukopenia) was the most commonly occurring adverse event (Sect. 5). Blood counts should be carefully monitored during pixantrone therapy and recombinant haematopoietic growth factors may be used if necessary [6].

The structural changes made to pixantrone (Sect. 2) do not appear to have completely eradicated the risk of cardiotoxicity [28], although the cardiotoxicity seen with pixantrone appears less frequent and less severe than that seen with other anthracenediones and anthracyclines [24, 26]. Asymptomatic reduction in LVEF was the most commonly reported cardiac adverse event in the heavily pretreated population of patients who received pixantrone in PIX301 (Sect. 5). Factors that may increase the risk of cardiotoxicity include active or dormant cardiovascular disease, prior treatment with anthracyclines or anthracenediones, prior or concurrent radiotherapy to the mediastinal area and concurrent use of other cardiotoxic drugs [6]. Before starting pixantrone, the risk versus benefit should be carefully considered in patients with cardiac disease or risk factors such as a baseline LVEF of <45 % by multigated radionuclide scan, clinically significant cardiovascular abnormalities (equivalent to New York Heart Association class 3 or 4), myocardial infarction within the previous 6 months, severe arrhythmia, uncontrolled hypertension or angina pectoris, or a prior cumulative doxorubicin dose equivalent of >450 mg/m2. Cardiac function should be monitored before starting treatment with pixantrone and periodically thereafter. If cardiotoxicity occurs during treatment, the risk versus benefit of continuing pixantrone therapy should be evaluated [6].

Based on the results of PIX301, pixantrone was granted conditional approval in the EU, with additional data requested to confirm the benefit of pixantrone in patients pretreated with rituximab [24]. In order to satisfy this requirement, a phase 3 study (PIX306; NCT01321541) was initiated comparing the efficacy of pixantrone plus rituximab with that of gemcitabine plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL who have received prior rituximab [2]. It is estimated that 260 patients will need to be enrolled to reach the required 195 PFS events (primary endpoint) [2]. Results of PIX306 are awaited with interest.

A UK multicentre retrospective analysis examined the use of pixantrone in a real-world setting [29]. Patients (n = 90) in this retrospective analysis had de novo DLBCL (63 %) or had transformed from indolent NHL (33 %) or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (4 %). Differences between this retrospective analysis and the PIX301 trial (e.g. patients in the retrospective analysis generally had poorer prognostic features) mean that comparisons between the retrospective analysis and PIX301 should be made with caution. In the retrospective analysis, 85 % of patients had refractory disease, 15 % had relapsed disease, 99 % had previously received rituximab, 90 % were Ann Arbor stage III–IV, and 6, 21 and 73 % had an IPI score of 0–1, 2 and 3–5, respectively. In addition, 70 % of patients had an ECOG performance status of 1 or 2, and patients had received a median of two prior chemotherapy regimens. Following treatment with pixantrone (median of two cycles), the ORR was 24 % and the median durations of PFS and OS were 2.0 and 3.4 months, respectively. Besides its retrospective design, other limitations of this analysis include a lack of centralized pathology review and a lack of formalized radiological reporting using established criteria [29].

Pixantrone was predicted to be cost effective versus comparator agents (vinorelbine, oxaliplatin, ifosfamide, etoposide, mitoxantrone or gemcitabine) for the third- or fourth-line treatment of multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL, according to the results of a UK pharmacoeconomic analysis conducted from a healthcare payer perspective [30].

Guidance from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends pixantrone as an option in adults with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL if the patient has previously received rituximab and is receiving third- or fourth-line treatment [25]. An Italian expert panel also recently concluded that the benefit : risk profile favours pixantrone in adults with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL [4].

In conclusion, pixantrone is a useful option in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell NHL. Further results examining the use of pixantrone in combination with rituximab in patients previously treated with rituximab-containing regimens are awaited with interest.

Data selection sources:

Relevant medical literature (including published and unpublished data) on pixantrone was identified by searching databases including MEDLINE (from 1946), PubMed (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1996) [searches last updated 10 October 2016], bibliographies from published literature, clinical trial registries/databases and websites. Additional information was also requested from the company developing the drug.

Search terms: Pixantrone, Pixuvri, BBR-2778, lymphoma, lymphatic reticulum-cell sarcoma.

Study selection: Studies in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma who received pixantrone. When available, large, well designed, comparative trials with appropriate statistical methodology were preferred. Relevant pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic data are also included.

References

Ghielmini M, Vitolo U, Kimby E, et al. ESMO Guidelines consensus conference on malignant lymphoma 2011 part 1: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Ann Oncol. 2013;24(3):561–76.

Belada D, Georgiev P, Dakhil S, et al. Pixantrone-rituximab versus gemcitabine-rituximab in relapsed/refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2016;12(15):1759–68.

Fanous I, Dillon P. Cancer treatment-related cardiac toxicity: prevention, assessment and management. Med Oncol. 2016;33(8):84.

Zinzani PL, Corradini P, Martelli M, et al. Critical concepts, practice recommendations and research perspectives of pixantrone therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a SIE, SIES. GITMO consensus paper. Eur J Haematol. 2016. doi:10.1111/ejh.12768.

Volpetti S, Zaja F, Fanin R. Pixantrone for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:865–72.

European Medicines Agency. Pixuvri (pixantrone): EU summary of product characteristics. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

Pettengell R, Kaur J. Pixantrone dimaleate for treating non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Exp Opin Orphan Drugs. 2015;3(6):747–57.

Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Minotti G. Rethinking drugs from chemistry to therapeutic opportunities: pixantrone beyond anthracyclines. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29(8):1270–8.

Salvatorelli E, Menna P, Paz OG, et al. The novel anthracenedione, pixantrone, lacks redox activity and inhibits doxorubicinol formation in human myocardium: insight to explain the cardiac safety of pixantrone in doxorubicin-treated patients. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344(2):467–78.

Evison BJ, Mansour OC, Menta E, et al. Pixantrone can be activated by formaldehyde to generate a potent DNA adduct forming agent. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35(11):3581–9.

Hasinoff BB, Wu X, Patel D, et al. Mechanisms of action and reduced cardiotoxicity of pixantrone; a topoisomerase II targeting agent with cellular selectivity for the topoisomerase IIα isoform. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356(2):397–409.

Beeharry N, Di Rora AGL, Smith MR, et al. Pixantrone induces cell death through mitotic perturbations and subsequent aberrant cell divisions. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(9):1397–406.

Beggiolin G, Crippa L, Menta E, et al. BBR 2778, an aza-anthracenedione endowed with preclinical anticancer activity and lack of delayed cardiotoxicity. Tumori. 2001;87(6):407–16.

Cavalletti E, Crippa L, Mainardi P, et al. Pixantrone (BBR 2778) has reduced cardiotoxic potential in mice pretreated with doxorubicin: comparative studies against doxorubicin and mitoxantrone. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25(3):187–95.

Longo M, Della Torre P, Allievi C, et al. Tolerability and toxicological profile of pixantrone (Pixuvri®) in juvenile mice: comparative study with doxorubicin. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;46:20–30.

Faivre S, Raymond E, Boige V, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the novel aza-anthracenedione compound BBR 2778 in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(1):43–50.

Borchmann P, Schnell R, Knippertz R, et al. Phase I study of BBR 2778, a new aza-anthracenedione, in advanced or refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(5):661–7.

Lim S-T, Fayad L, Tulpule A, et al. A phase I/II trial of pixantrone (BBR2778), methylprednisolone, cisplatin, and cytosine arabinoside (PSHAP) in relapsed/refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(2):374–80.

Dawson LK, Jodrell DI, Bowman A, et al. A clinical phase I and pharmacokinetic study of BBR 2778, a novel anthracenedione analogue, administered intravenously, 3 weekly. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(18):2353–9.

Borchmann P, Morschhauser F, Parry A, et al. Phase-II study of the new aza-anthracenedione, BBR 2778, in patients with relapsed aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Haematologica. 2003;88(8):888–94.

Pettengell R, Coiffier B, Narayanan G, et al. Pixantrone dimaleate versus other chemotherapeutic agents as a single-agent salvage treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 3, multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(7):696–706.

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1244.

Pettengell R, Sebban C, Zinzani PL, et al. Monotherapy with pixantrone in histologically confirmed relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: post-hoc analyses from a phase III trial. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(5):692–9.

European Medicines Agency. Pixuvri (pixantrone): CHMP assessment report. 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pixantrone monotherapy for treating multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/TA306. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

Péan E, Flores B, Hudson I, et al. The European Medicines Agency review of pixantrone for the treatment of adult patients with multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas: summary of the scientific assessment of the committee for medicinal products for human use. Oncologist. 2013;18(5):625–33.

Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4184–90.

Beaven AW, Rizzieri D. Clinical evidence for the role of pixantrone in the treatment of relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Invest. 2012;2(1):49–58.

Eyre TA, Linton KM, Rohman P, et al. Results of a multicentre UK-wide retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of pixantrone in relapsed, refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016;173(6):896–904.

Muszbek N, Kadambi A, Lanitis T, et al. The cost-effectiveness of pixantrone for third/fourth-line treatment of aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Ther. 2016;38(3):503–15.

Acknowledgments

During the peer review process, the manufacturer of pixantrone was also offered an opportunity to review this article. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Conflict of interest

Gillian Keating is a salaried employee of Adis/Springer, is responsible for the article content and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional information

The manuscript was reviewed by: C. Gisselbrecht, Institut d’Hématologie Hopital Saint Louis, Paris, France; R. Herbrecht, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Hôpital de Hautepierre and Université de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France; P.L. Zinzani, Institute of Hematology “Seragnoli”, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keating, G.M. Pixantrone: A Review in Relapsed or Refractory Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Drugs 76, 1579–1586 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-016-0650-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-016-0650-8