Abstract

The large-scale use of social media by the population has gained the attention of stakeholders and researchers in various fields. In the domain of pharmacovigilance, this new resource was initially considered as an opportunity to overcome underreporting and monitor the safety of drugs in real time in close connection with patients. Research is still required to overcome technical challenges related to data extraction, annotation, and filtering, and there is not yet a clear consensus concerning the systematic exploration and use of social media in pharmacovigilance. Although the literature has mainly considered signal detection, the potential value of social media to support other pharmacovigilance activities should also be explored. The objective of this paper is to present the main findings and subsequent recommendations from the French research project Vigi4Med, which evaluated the use of social media, mainly web forums, for pharmacovigilance activities. This project included an analysis of the existing literature, which contributed to the recommendations presented herein. The recommendations are categorized into three categories: ethical (related to privacy, confidentiality, and follow-up), qualitative (related to the quality of the information), and quantitative (related to statistical analysis). We argue that the progress in information technology and the societal need to consider patients’ experiences should motivate future research on social media surveillance for the reinforcement of classical pharmacovigilance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The analysis of social media may be considered as an adjunct to other data sources for certain specific pharmacovigilance activities, even though its return on investment is questionable when performing signal detection. |

The use of social media for pharmacovigilance should consider aspects related to ethical constraints, the quality of the information, and limitations related to quantitative analysis. |

Social media is a promising resource for the collection of nonserious adverse drug reactions that influence patients’ quality of life and needs to be considered for patient-oriented medicine. |

1 Introduction

The recent evolution of social media and the development of new automated approaches in natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning have motivated research on the usefulness of social media for pharmacovigilance activities. In the literature, researchers have shown interest in considering data extracted from the web as a new resource for evaluating adverse drug reactions (ADRs). For example, Medawar et al. [1] evaluated emails sent by users in reaction to a TV program about paroxetine compared with online-user posts concerning the same drug before the program was broadcast. This early paper suggested considering people’s experiences to improve drug safety and efficiency. Emerging approaches in computer science have also reflected an interest in detecting ADRs from online data. For example, Curino et al. [2] proposed a web-mining system that uses neural networks (a machine-learning approach) to find unknown ADRs from web pages.

As use of the internet has evolved, it has become common to share and exchange opinions via online platforms that we refer to as “social media,” such as web forums, Twitter, and Facebook. Health-related issues are now often discussed in these online communities, including patients’ experiences with drugs and ADRs. Schröder et al. [3] were the first to analyze the content of social media for pharmacovigilance. They performed a retrospective analysis of online forum posts spanning 1 year to detect ADRs of antiparkinsonian agents. Twitter was first explored for ADR detection by Scanfeld et al. [4], who reviewed and grouped 1000 tweets to analyze misunderstandings about or misuse of antibiotics. The analysis in these early papers was manual. Leaman et al. [5] reported the first automatic approach to detecting ADRs from social media in 2010. This study applied NLP and text mining of web forum posts to compare ADRs detected in user posts and documented ADRs.

Despite the high number of studies on the use of social media in pharmacovigilance, none of the review papers that evaluated these studies confirmed or refuted the utility of systematically monitoring and analyzing user posts for pharmacovigilance activities. For example, Golder et al. [6] concluded that, although social media allows the identification of ADRs, the validity and reliability of these ADRs are yet to be proven. Sloane et al. [7] shared the same concern about the challenging nature of the data collected from social media and concluded that the benefit of social media for pharmacovigilance will depend on the technological approach used to process the data. The scoping review of Lardon et al. [8] showed that gaps remain in the field and that additional studies are required to precisely determine the role of social media in the pharmacovigilance system. In 2018, Convertino et al. [9] highlighted the poor quality of the data from social media and did not recommend its use in signal detection for routine pharmacovigilance, whereas Tricco et al. [10] showed that this resource has the potential to supplement data from regulatory agency databases, although the utility and validity of this data source remains understudied. Finally, Pappa and Stergioulas [11] showed key challenges and provided insights for the use of social media in pharmacovigilance and expected social media monitoring to become standard practice in the future.

The objective of this paper is to present findings and recommendations based on the experience of Vigi4Med, a publicly funded French research project that evaluated the use of social media, mainly web forums, in pharmacovigilance. These recommendations apply to some or all pharmacovigilance activities, i.e., ADR report management, healthcare or patient information, surveillance, signal detection, risk management, and regulatory actions (definitions of these activities are in Appendix 1 in the electronic supplementary material [ESM]).

2 Existing Recommendations and Advice

Several recommendations and advice on the use of social media in pharmacovigilance already exist in the literature. In 2011, Micoulaud-Franchi was the first to present advice about the necessary evolution of pharmacovigilance during the Web 2.0 era [12]. This author encouraged the consideration of patient ADR descriptions in social media to improve current pharmacovigilance activities. The first recommendations concerning the way social media should be evaluated in pharmacovigilance activities were proposed in June 2016 by a think tank on “Enabling Social Listening for Cardiac Safety Monitoring,” cosponsored by the Drug Information Association and the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium [13]. Although this paper suggested considering social media as an add-on to spontaneous reports or, alternatively, using this source independently for hypothesis generation and signal detection, it focused mainly on the shortcomings of these areas. Bousquet et al. [14] proposed that five main challenges should be taken into account when working on ADRs in social media: the quality of the information, data privacy, the identification of relevant information, the construction of a robust architecture, and the expectations of pharmacovigilance experts.

Recently, health authorities in France and Europe started questioning the possibility of using digital information from the internet for pharmacovigilance activities. After a national media-hyped crisis related to the new formulation of Levothyrox®, the French health ministry set up an expert mission to study and improve information available for patients and health professionals [15]. One of their recommendations was to consider so-called nonofficial resources for pharmacovigilance, such as social networks, web forums, and blogs. It suggested that, although the utility of these data for signal detection was still not demonstrated, research was likely to lead to new artificial intelligence methods that would enable social media to complement current pharmacovigilance techniques. In Europe, the Guidelines to Good Pharmacovigilance Practices indicated that “marketing authorization holders should regularly screen the internet or digital media under their management or responsibility” [16]. In 2019, the Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA)/European Medicines Agency (EMA) Joint Big Data Taskforce, within the Mobile-Health Data subgroup, proposed medium- and high-priority recommendations and actions for the use of social media for pharmacovigilance. These recommendations described needed implementation, essentially for signal detection, communication via social media, and ethical data access and extraction [17].

Finally, the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) European project WEB-RADR [18] established a large-scale study to evaluate whether social media improves signal detection relative to that based on the World Health Organization global pharmacovigilance database (VigiBase). This project mainly used Twitter (65%) and Facebook (35%) and focused more on quantitative than on qualitative aspects (number of available posts vs. information available in posts, respectively). Caster et al. [19] showed that signals are usually detected in social media after they are detected in VigiBase. They concluded that the use of social media, particularly Facebook and Twitter, should not be part of routine signal detection in pharmacovigilance. This conclusion was later included as one of the IMI WEB-RADR project recommendations when addressing the issue of signal detection and adverse event (AE) recognition in social media [20].

All previous publications show the difficulty of providing evidence of the utility of social media in pharmacovigilance. Social media currently do not seem to be a reliable resource for specific purposes such as signal detection, but future technologies could make a difference. The potential utility of social media could also be evaluated for other pharmacovigilance activities for which this resource has not yet been explored.

In parallel to the IMI WEB-RADR project, the goal of the Vigi4Med project was to evaluate whether the posts from medical web forums could be used as a complementary source of information by health authorities for drug monitoring. In France, qualitative review of individual ADR cases is a major source for signal detection and is historically performed by regional pharmacovigilance centers. Unlike WEB-RADR, Vigi4Med focused mainly on the qualitative aspect of social media. The content of a series of posts mentioning potential ADRs was analyzed for the presence of relevant information required for characterizing a pharmacovigilance case report. In particular, Vigi4Med analyzed the seriousness of the ADRs and was the first project to evaluate causality of a large number of posts based on temporal association between the drug and the AE and bibliographical evidence. Although the qualitative evaluation concerned fewer drugs than analyzed by WEB-RADR, analyses in the Vigi4Med project were facilitated by the use of web forums in which user posts were not limited by the number of characters and generally contained more context than those in other social networks, such as Twitter.

In Appendix 1 in the ESM, we provide a non-exhaustive summary of the main recommendations and advice from previous publications (Table 1.1 in Appendix 1) and the originality of our recommendations relative to the state of the art (Table 1.2 in Appendix 1).

3 The Vigi4Med Project: Methods and Key Findings

3.1 General Description and Methods

Vigi4Med aimed to analyze the utility of social media for pharmacovigilance. The consortium included two regional pharmacovigilance centers and five partners specialized in medical informatics, automatic language processing, and the semantic web, which set up the technical infrastructure that allowed the retrieval, filtering, and analysis of patient comments on web forums. The stages of the project were as follows:

-

1.

Selection of the web forums: the main target in this project was French websites that host public health-related discussion forums. They were chosen either by an online search using Google (using the terms “drug” AND “adverse drug reaction” OR “adverse event” AND “forum”) or by examining the list of health websites certified by the Health On the Net Foundation in collaboration with the French National Health Authority. Sites not hosted in France, those containing fewer than ten patient contributions or only accessible by health professionals were excluded [21]. As a result, 21 general or specialized French web forums were considered in the project.

-

2.

Data extraction and anonymization: Vigi4Med Scraper [22], an open source software, was designed and implemented to extract user posts from the selected discussion forums. This software automatically handled page flipping, data storage with semantic representation, and anonymization of the users’ pseudonyms. It allowed the extraction of over 60 million posts from the selected forums.

-

3.

Automatic detection of drugs and AEs: The implemented approach used two classifiers: conditional random fields to detect medical-related entities, and support vector machines to detect the relationships between the entities that form a complex medical condition. Evaluation of the first classifier on a corpus of French drug reviews (meamedica.fr) indicated precision of 0.926 and recall of 0.849, whereas the second classifier obtained 0.683 and 0.956, respectively [23]. The loss in precision and recall related to normalization of users’ verbatim text (drugs and AEs) to standardized terminologies was not evaluated.

-

4.

Qualitative analysis of posts and potential ADR cases: Several drugs of interest were chosen for a “case study.” Two complementary approaches were selected: a retrospective analysis of posts for two drugs with a known/expected signal (tetrazepam and baclofen), and a prospective analysis of four drugs with identified risks but of no particular safety concern (agomelatine, duloxetine, exenatide, and strontium ranelate).

3.2 Vigi4Med Key Findings

After data extraction and automatic annotation, we performed a qualitative analysis of social media and compared it to the data from the French pharmacovigilance database (FPVD). Our case study consisted of evaluating the information shared by patients in web forums and its potential utility in pharmacovigilance for the six aforementioned drugs [21]. In total, pharmacovigilance specialists manually evaluated 5149 posts. These posts were chosen by random sampling, manual selection, or application of the proportional reporting ratio (PRR) algorithm. It is important to mention that manual review of posts is time consuming and requires professionals qualified (or trained) in pharmacovigilance. It only can be applied to a predefined set of drugs and a limited number of posts.

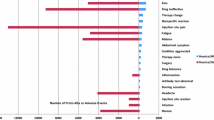

The 1284 posts classified as potential pharmacovigilance cases in web forums were compared with 2512 reports from the FPVD for the same drugs. Cases from the web forums were mostly non-serious (95.8 vs. 54.4% in the FPVD). The mean number of reactions was the same for both sources (2.3 per case in forums vs. 2.1 in the FPVD). However, if patients accurately described their experiences in web forums, they used fewer categories of ADRs, mostly attached to three main system organ classes from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (nervous system disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, and general disorders). Nevertheless, the close analysis of all potential cases showed unexpected adverse effects for some drugs (24.2 vs. 17.1% in the FPVD), e.g., inefficacy and worsened condition with the two antidepressants (agomelatine and duloxetine), a withdrawal syndrome with agomelatine, abuse with tetrazepam, and alopecia and nail disorders for baclofen. Two reactions (alcohol abuse and impulse-control disorder) were associated with agomelatine but could also be associated with the indication of the antidepressant. Finally, we also retrieved information about potential drug misuse, e.g., agomelatine used for insomnia, baclofen for eating disorders, and exenatide for weight loss.

The analysis of posts associated with the six drugs selected for this study showed a significant number of AEs that are (1) non-serious but affect patient quality of life and (2) usually not reported by health professionals. Based on these observations, we concluded that web forums can be a useful source to investigate ADRs that affect the patient quality of life and medication adherence. Our experience in quantitative analysis was limited to a single study on signal detection with baclofen, in which we did not evaluate whether the signals were detected before or after their detection in the FPVD [24]. However, one major finding of this study was the need to account for the various ways that patients mention drugs in web forums. Indeed, adding lexical variations of “baclofène” (French spelling for baclofen) such as “baclo,” “Baklo,” or “Baclofen” led to the detection of 40,158 additional drug–AE couples compared with searching with only the exact match “baclofène.”

In another study, we analyzed the most often-mentioned drugs in user posts, their correlation with the most highly prescribed drugs in France, and whether the evolution of the frequency of drug mentions over time corresponded to events reported in the traditional media [25]. The aim of this investigation was to evaluate the potential of social media for postmarketing studies. As suggested by Bate et al. [26], such investigations could help “identify the best uses of these data for pharmacovigilance, including which patient populations, outcomes, or medicines are best suited to using social media for signal detection.” Our analysis showed that the most discussed drugs in these online communities in France are those generally prescribed to young women (such as oral contraceptives). Our comparison of the most often-mentioned drugs in social media versus the most prescribed drugs in France showed a discrepancy. This result might have important consequences in constraining the scope of studies to drugs that are the most frequently mentioned and to the populations that primarily use them rather than broad-ranging studies. Furthermore, we analyzed the frequency of the mentions of baclofen, Champix® (varenicline) and Mirena® (a copper intrauterine device) from July 2007 to May 2015 and compared the evolution of mentioning the “old” versus “new” generations of combined oral contraceptives in these forums. This analysis showed that the frequency of a drug mention was highly influenced by newscasts and popular events in the media. Our study revealed the need to consider the ambiguity in patient language and the choice of web forums, depending on the drug being studied.

Recently, we explored user posts in a forum of patients requiring thyroid hormone therapy to check whether the health crisis concerning the new formulation of Levothyrox® in France could have been anticipated [27]. Our preliminary analyses on the frequency of AE mentions in posts related to Levothyrox® showed an increase in the frequency of non-serious AEs during the period corresponding to the crisis. A huge rise in spontaneous reports to the pharmacovigilance network was observed in parallel. However, a specific analysis of the temporality of reports must be performed to evaluate the potential use of social media as a precocious signal [27].

In addition to web forums, the project conducted an ancillary study of Twitter [28], in which 10,534 tweets were extracted using the streaming application programming interface (API) and manually analyzed by the two pharmacovigilance regional centers. Among these tweets, 8.05% mentioned an ADR but no personal experience; 2.74% (289 tweets) could be considered valid case reports, as they met the four minimum criteria (i.e., an identifiable patient, an identifiable reporter, at least one suspect drug, and at least one suspect ADR). Among these 289 potential case reports, 20 (7.27%) mentioned an unexpected ADR, i.e., they were not documented in the corresponding French summaries of product characteristics available during the study period, and nine mentioned an ADR not reported in the standard reference Martindale and Drugdex databases or FPVD (e.g., “macular degeneration” with rivaroxaban, “gynecomastia” with ustekinumab). In this study, we highlighted interest in using Twitter as a complementary resource in pharmacovigilance, the technical challenges in extracting potentially relevant data from this source (e.g., misspellings, use of abbreviations), and the difficulty of causality assessment, mainly because of restriction on the length of tweets.

4 Methodological Approach to Writing the Recommendations

The recommendations presented in this paper were established using the following approach. First, four pharmacovigilance professionals (FB, MNB, ALL, and CB) from the Vigi4Med consortium located in three distinct sites independently drafted recommendations concerning the use of social media for pharmacovigilance purposes based on their experiences in the project. A shared document containing all the proposed recommendations was then exchanged among the professionals, allowing them to modify or confirm the recommendations. In case of disagreement, a consensus was established through direct discussions. Then, a computer-science researcher from the Vigi4Med consortium (BA) re-examined the recommendations from a neutral point of view.

With this new vision, all the authors worked on reformulating the recommendations, clarifying and organizing them into three areas: ethical, qualitative, and quantitative. In addition to improving the presentation, the choice of these areas aimed to draw attention to the critical aspect of protecting user privacy, in accordance with recent European legislation, and the importance of qualitatively evaluating [29] the information when analyzing social media for pharmacovigilance. Indeed, most previous studies focused on the quantitative aspect (number of posts), mainly for signal detection. Nevertheless, clinical review of case reports is still necessary to validate suspected signals, assess causality, and evaluate the potential impact of social media on decision making [21].

5 Recommendations Concerning the Use of Social Media in Pharmacovigilance

The recommendations related to each of the three axes (ethical, qualitative, and quantitative) are presented in tables consisting of four columns. Recommendations and their rationales appear in the first and second columns, respectively. The last column (activity) shows the pharmacovigilance activity(ies) to which the recommendation applies, and the column “rationale source” can include one or more of the following values:

-

E: if the rationale is based on a confirmed experience from the Vigi4Med project.

-

L: if the literature contains evidence that supports the rationale.

-

O: if the recommendation represents our opinion. In this case, the rationale is based not on empirical findings but on observations from our preliminary experience or theoretical arguments from the literature with insufficient evidence.

Certain recommendations in this section are “practical” for the use of social media as a resource in specific pharmacovigilance applications. Others aim to give directions for future research in pharmacovigilance activities for which, in our experience, the use of social media has not been sufficiently explored.

5.1 Ethics and Data Protection

Ethical and data protection aspects to apply for the use of public social media data are related to privacy, confidentiality, and follow-up restrictions. In the EU, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [30] (applied since 25 May 2018) imposes several rules to consider for any process that involves personal information, including health data. Pharmacovigilance organizations for which the GDPR does not apply should consider their own national legislation. Table 1 shows our recommendations for the ethical aspects of the use of social media in pharmacovigilance.

5.2 Qualitative Aspects

From a qualitative point of view, any missing information hinders the assessment of causality and the usefulness of the case, regardless of the data source. This is particularly true for topics of high interest in pharmacovigilance (drug exposure during pregnancy/breastfeeding, drug misuse, or drug adherence). Table 2 shows our recommendations for the use of social media in pharmacovigilance from such a qualitative point of view.

5.3 Quantitative Aspects

Quantitative aspects are related to all statistical analyses on social media for pharmacovigilance, such as counting the frequency of drug or event mentions in forums, time series analysis, and signal detection. Social media are considered to be valuable for pharmacovigilance if they (1) allow detection of signals before they appear in the usual data sources or (2) provide additional information about adverse drug events that are unexpected or poorly documented. Table 3 shows our recommendations for the use of social media in pharmacovigilance from the quantitative point of view.

6 Discussion

In this paper, we aimed to share recommendations concerning the use of social media in the current practice of pharmacovigilance based not only on our experience in Vigi4Med but also on an extensive analysis of the literature. We believe that these recommendations could be useful for (1) researchers in computer science and information technology who need to account for pharmacovigilance expectations when implementing frameworks for the use of social media and (2) stakeholders in pharmacovigilance. We propose new perspectives for research that have not yet been addressed or have not received sufficient attention. We consider that future research on specific pharmacovigilance issues should be transferred in operational settings in the same way signal detection was eventually implemented in pharmacovigilance activities. For example, social media could be evaluated for topics such as quality of life, drug misuse, and drug exposure in pregnancy and breastfeeding. We clarified the added value of social media and how it can be used successfully to support various pharmacovigilance activities. We identified three critical themes: addressing ethical issues, the importance of considering data quality and patients’ expectations, and the limited advantage of social media for statistical signal detection using existing approaches.

Although most published studies have focused mainly on the quantitative aspect, the Vigi4Med project analyzed the content of a large number of posts, allowing us to draw attention to the importance of the patient’s voice, even for non-serious AEs, in improving their quality of life. An interesting example that highlights the importance of the patient’s voice is the recent Levothyrox® crisis in France. In August 2017, a French newspaper triggered a highly media-hyped situation concerning the new formulation of Levothyrox®, a levothyroxine-based drug commercialized in France since March 2017. More than 300,000 citizens signed an online petition supporting retaining the old formulation. Although the ADRs were not life threatening and were mostly already mentioned in the summary of product characteristics, patients were largely mobilized as their quality of life was affected.

The WEB-RADR project [19] evaluated that broad-ranging statistical signal detection with Twitter and Facebook is not recommended. As mentioned, Van Stekelenborg et al. [20] published recommendations based on their experience in WEB-RADR, in which NLP and large-scale signal detection were applied to several social media. Unlike WEB-RADR, we mainly addressed issues related to information available in posts to determine whether the content was sufficient for causality and impact assessment and, ultimately, whether social media can be integrated into signal evaluation and decision making. Also unlike WEB-RADR, which analyzed mainly Twitter and Facebook, the Vigi4Med project focused on web forums, for which machine learning was used in addition to NLP to detect drug and AE mentions in user posts. As forum posts are not restricted in terms of their length, unlike Twitter, they provide more data to help assess potential causality. The HMA/EMA Joint Big Data Taskforce has recently reinforced the need to “investigate a wider range of social media data sources, particularly patient forums” [17].

Our position, based on our experience in the Vigi4Med project, is to support the WEB-RADR conclusions concerning the globally low quality of social media data for signal detection. We agree that the return on investment of analysis of social media is questionable when performing quantitative signal detection. However, we believe that the use of social media is inevitable and a promising method for considering the complaints and feelings of users that may not be a priority for health professionals. In addition, information from social media could be used to analyze the misuse of drugs by the population and how online users influence or react to medical hot topics and new health products. Further research to improve the automatic detection of drugs, diseases, events, and feelings, based on machine learning and NLP, is thus merited [81].

Some limitations regarding generalization of recommendations cited in this paper should be considered. For example, we did not account for duplicate detection or evaluate whether our automatic annotation detected both rare and common AEs. In addition, we did not evaluate the temporality of social media relative to that of classical pharmacovigilance sources: it is important to know whether certain signals from social media may appear earlier and therefore allow for more reactive analysis and regulatory action. Nevertheless, although data extracted and used in the Vigi4Med project were mainly limited to one type of social media (web forums) and restricted to France, our conclusions were supported by the large number of posts collected from several web forums and manually analyzed by physicians and pharmacists trained in pharmacovigilance.

We believe that any future studies on social media should consider the rapidly growing volume of data and the technical challenges of extracting and annotating such data. Generalization of our recommendations requires additional experience on use cases that consider large sets of drugs and/or diseases. Future research should also focus on patients’ perspectives and opinions about drugs and how medical treatment affects their quality of life.

References

Medawar C, Herxheimer A, Bell A, Jofre S. Paroxetine, Panorama and user reporting of ADRs: consumer intelligence matters in clinical practice and post-marketing drug surveillance. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2002;15(4/3):161–9.

Curino CA, Jia Y, Lambert B, West PM, Yu C. Mining officially unrecognized side effects of drugs by combining web search and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM international conference on Information and knowledge management. 2005. p. 365–72.

Schröder S, Zöllner YF, Schaefer M. Drug related problems with Antiparkinsonian agents: consumer internet reports versus published data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(10):1161–6.

Scanfeld D, Scanfeld V, Larson EL. Dissemination of health information through social networks: Twitter and antibiotics. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):182–8.

Leaman R, Wojtulewicz L, Sullivan R, Skariah A, Yang J, Gonzalez G. Towards internet-age pharmacovigilance: extracting adverse drug reactions from user posts to health-related social networks. In: Proceedings of the 2010 workshop on biomedical natural language processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2010. p. 117–25.

Golder S, Norman G, Loke YK. Systematic review on the prevalence, frequency and comparative value of adverse events data in social media. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):878–88.

Sloane R, Osanlou O, Lewis D, Bollegala D, Maskell S, Pirmohamed M. Social media and pharmacovigilance: a review of the opportunities and challenges. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):910–20.

Lardon J, et al. Adverse drug reaction identification and extraction in social media: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(7):1–16.

Convertino I, Ferraro S, Blandizzi C, Tuccori M. The usefulness of listening social media for pharmacovigilance purposes: a systematic review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(11):1081–93.

Tricco AC, et al. Utility of social media and crowd-intelligence data for pharmacovigilance: a scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(1):1–14.

Pappa D, Stergioulas LK. Harnessing social media data for pharmacovigilance: a review of current state of the art, challenges and future directions. Int J Data Sci Anal. 2019;8:113–35.

Micoulaud-Franchi JA. Un pas de plus vers une pharmacovigilance 2.0. Intégration des données du web communautaire à une pharmacovigilance plus alerte. Press Medicale. 2011;40(9):790–2.

Seifert HA, et al. Enabling social listening for cardiac safety monitoring: Proceedings from a drug information association-cardiac safety research consortium cosponsored think tank. Am Heart J. 2017;194:107–15.

Bousquet C, et al. The adverse drug reactions from patient reports in social media project: five major challenges to overcome to operationalize analysis and efficiently support pharmacovigilance process. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(9):e179.

Kierzek G, Leo M. Rapport sur l’amélioration de l’information des usagers et des professionnels de santé sur le médicament. Mission report 2018 [Online]. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/180903_-_mim_rapport.pdf. Accessed May 2020.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP)—Module VI—collection, management and submission of reports of suspected adverse reactions to medicinal products (Rev 2). London: EMA; 2017.

European Medicines Agency. HMA-EMA Joint Big Data Taskforce-summary report Summary report. London: EMA; 2019.

Ghosh R, Lewis D. Aims and approaches of Web-RADR: a consortium ensuring reliable ADR reporting via mobile devices and new insights from social media. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(12):1845–53.

Caster O, et al. Assessment of the utility of social media for broad-ranging statistical signal detection in pharmacovigilance: results from the WEB-RADR Project. Drug Saf. 2018;41(12):1355–69.

van Stekelenborg J, et al. Recommendations for the use of social media in pharmacovigilance: lessons from IMI WEB-RADR. Drug Saf. 2019;42(12):1393–407.

Karapetiantz P, et al. Descriptions of adverse drug reactions are less informative in forums than in the French Pharmacovigilance database but provide more unexpected reactions. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1–11.

Audeh B, Beigbeder M, Zimmermann A, Jaillon P, Bousquet CD. “Vigi4Med Scraper: a framework for web forum structured data extraction and semantic representation. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169658.

Morlane-Hondère F, Grouin C, Zweigenbaum P. Identification of drug-related medical conditions in social media. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'16). 2016. p. 2022–8.

Karapetiantz P, Audeh B, Louët AL-L, Bousquet C. Signal detection for baclofen in web forums: a preliminary study. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;247:421–5.

Audeh B, et al. Pharmacology and social media: Potentials and biases of web forums for drug mention analysis—case study of France. Health Inform J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458219865128.

Bate A, Reynolds RF, Caubel P. The hope, hype and reality of Big Data for pharmacovigilance. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(1):5–11.

Audeh B et al. French Levothyrox® crisis: retrospective analysis of social media. In: International Society of Pharmacovigilance. 2019.

Lardon J, et al. Evaluating Twitter as a complementary data source for pharmacovigilance. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(8):763–74.

Edwards IR, Lindquist M, Wiholm BE, Napke E. Quality criteria for early signals of possible adverse drug reactions. Lancet. 1990;336(8708):156–8.

The european parliament and the council of the european union. Regulation (eu) 2016/679 of the european parliament and of the council of 27 april 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing directive 95/46/ec (general da, Official Journal of the European Union, 2016. [Online]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679. Accessed May 2020.

Golder S, Scantlebury A, Christmas H. Understanding public attitudes toward researchers using social media for detecting and monitoring adverse events data: multi methods study. Journal of medical Internet research. 2019;21(8):e7081.

Lengsavath M, et al. Social media monitoring and adverse drug reaction reporting in pharmacovigilance: an overview of the regulatory landscape. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(1):125–31.

Naik P, et al. Regulatory definitions and good pharmacovigilance practices in social media: challenges and recommendations. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2015;49(6):840–51.

Brosch S, de Ferran AM, Newbould V, Farkas D, Lengsavath M, Tregunno P. Establishing a framework for the use of social media in pharmacovigilance in Europe. Drug Saf. 2019;42:921–30.

Azam R. Accessing social media information for pharmacovigilance: what are the ethical implications? Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(6):259–61.

Kheloufi F, Default A, Blin O, Micallef J. Investigating patient narratives posted on Internet and their informativeness level for pharmacovigilance purpose: the example of comments about statins. Therapie. 2017;72(4):483–90.

Sadah SA, Shahbazi M, Wiley MT, Hristidis V. Demographic-based content analysis of web-based health-related social media. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):1–13.

Sinclair M, Lagan BM, Dolk H, McCullough JEM. An assessment of pregnant women’s knowledge and use of the Internet for medication safety information and purchase. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(1):137–47.

Keller MS, Mosadeghi S, Cohen ER, Kwan J, Spiegel BMR. Reproductive health and medication concerns for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: thematic and quantitative analysis using social listening. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e206.

Rezaallah B, Lewis DJ, Pierce C, Zeilhofer HF, Berg BI. Social media surveillance of multiple sclerosis medications used during pregnancy and breastfeeding: thematic qualitative analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(8):e13003.

Bigeard E, Grabar N, Thiessard F. Detection and analysis of drug misuses. A study based on social media messages. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1–16.

Zhao M, Yang CC. Automated off-label drug use detection from user generated content. In: Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics. 2017. p. 449–54.

Campillos-llanos L, Grouin C, Louët AL, Zweigenbaum P. Initial experiments for pharmacovigilance analysis in social media using summaries of product characteristics. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;264:60–64.

Cameron D, et al. PREDOSE: a semantic web platform for drug abuse epidemiology using social media. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46(6):985–97.

Zhao M, Yang CC. Exploiting OHC data with tensor decomposition for off-label drug use detection. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI). IEEE, 2018. p. 22–8.

Bigeard É, Thiessard F, Grabar N. Detecting drug non-compliance in internet fora using information retrieval and machine learning approaches. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;264:30–4.

Sarker A, et al. Social media mining for toxicovigilance: automatic monitoring of prescription medication abuse from twitter. Drug Saf. 2016;39(3):231–40.

Anderson L, et al. Using social listening data to monitor misuse and nonmedical use of bupropion: a content analysis. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2017;3(1):e6.

Sarker A, DeRoos A, Perrone J. Mining social media for prescription medication abuse monitoring: a review and proposal for a data-centric framework. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(2):315–29.

Abdellaoui R, Foulquie P, Texier N, Faviez C, Burgun A, Schück S. Detection of cases of noncompliance to drug treatment in patient forum posts: topic model approach. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):1–12.

Rees S, Mian S, Grabowski N. Using social media in safety signal management: is it reliable? Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(10):591–9.

Patel R, et al. Frequent discussion of insomnia and weight gain with glucocorticoid therapy: an analysis of Twitter posts. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1(1):20177.

Park SH, Hong SH. Identification of primary medication concerns regarding thyroid hormone replacement therapy from online patient medication reviews: text mining of social network data. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10):1–10.

Isah H, Trundle P, Neagu D. Social media analysis for product safety using text mining and sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings 2014 14th UK Work Comput Intell (UKCI). IEEE, 2014. p. 1–7.

Antipov EA, Pokryshevskaya EB. The effects of adverse drug reactions on patients’ satisfaction: evidence from publicly available data on Tamiflu (oseltamivir). Int J Med Inform. 2019;125:30–6.

Bousquet C, Audeh B, Bellet F, Louët AL-L. Comment on: ‘Assessment of the Utility of Social Media for Broad-Ranging Statistical Signal Detection in Pharmacovigilance: results from the WEB-RADR Project. Drug Saf. 2018;41(12):1355–69.

Moncrieff J, Cohen D, Mason JP. The subjective experience of taking antipsychotic medication: a content analysis of Internet data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(2):102–11.

Du J, Xu J, Song HY, Tao C. Leveraging machine learning-based approaches to assess human papillomavirus vaccination sentiment trends with Twitter data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(Suppl 2):69.

Booth A, et al. Using social media to uncover treatment experiences and decisions in patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: patient-centric qualitative data analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(11):1–12.

Golomb BA, Mcgraw JJ, Evans MA, Dimsdale JE. Physician response to patient reports. Drug Saf. 2007;30(8):669–75.

Vaughan Sarrazin MS, Cram P, Mazur A, Ward M, Reisinger HS. Patient perspectives of dabigatran: analysis of online discussion forums. Patient. 2014;7(1):47–544.

Abou Taam M, et al. Analysis of patients’ narratives posted on social media websites on benfluorex’s (Mediator®) withdrawal in France. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(1):53–5.

Bhattacharya M, et al. Using social media data in routine pharmacovigilance: a pilot study to identify safety signals and patient perspectives. Pharmaceut Med. 2017;31(3):167–74.

Topaz M, et al. Clinicians’ reports in electronic health records versus patients’ concerns in social media: a pilot study of adverse drug reactions of aspirin and atorvastatin. Drug Saf. 2015;39(3):243–50.

Tafti AP, et al. Adverse drug event discovery using biomedical literature: a big data neural network adventure. JMIR Med Inform. 2017;5(4):e51.

Smith K, Golder S, Sarker A, Loke Y, O’Connor K, Gonzalez-Hernandez G. Methods to compare adverse events in Twitter to FAERS, drug information databases, and systematic reviews: proof of concept with adalimumab. Drug Saf. 2018;41(12):1397–410.

Nikfarjam A, et al. Early detection of adverse drug reactions in social health networks: a natural language processing pipeline for signal detection. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2019;5(2):e11264.

Duh MS, et al. Can social media data lead to earlier detection of drug-related adverse events? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(12):1425–33.

Gavrielov-Yusim N, et al. Comparison of text processing methods in social media–based signal detection. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2019;28(10):1309–17.

Wu H, Fang H, Stanhope SJ. Exploiting online discussions to discover unrecognized drug side effects. Methods Inf Med. 2013;52(2):152–9.

Yang H, Yang CC. Using health-consumer-contributed data to detect adverse drug reactions by association mining with temporal analysis. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2015;6(4):55.

Feldman R, Netzer O, Peretz A, Rosenfeld B. Utilizing text mining on online medical forums to predict label change due to adverse drug reactions. In: Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (KDD), 2015. p. 1779–88.

Ransohoff JD, et al. Detecting chemotherapeutic skin adverse reactions in social health networks using deep learning. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(4):581–3.

Golder S, et al. Pharmacoepidemiologic evaluation of birth defects from health-related postings in social media during pregnancy. Drug Saf. 2019;42(3):389–400.

Pinheiro LC, Candore G, Zaccaria C, Slattery J, Arlett P. An algorithm to detect unexpected increases in frequency of reports of adverse events in EudraVigilance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(1):38–45.

Trinh NTH, Solé E, Benkebil M. Benefits of combining change-point analysis with disproportionality analysis in pharmacovigilance signal detection. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(3):370–6.

Barry D, Hartigan JA. A Bayesian analysis for change point problems. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):309–19.

Butt TF, Cox AR, Oyebode JR, Ferner RE. Internet accounts of serious adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf. 2012;35(12):1159–70.

Comfort S, et al. Sorting through the safety data haystack: using machine learning to identify individual case safety reports in social-digital media. Drug Saf. 2018;41(6):579–90.

Cocos A, Fiks AG, Masino AJ. Deep learning for pharmacovigilance: recurrent neural network architectures for labeling adverse drug reactions in Twitter posts. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(4):813–21.

Sarker A, et al. Data and systems for medication-related text classification and concept normalization from Twitter: insights from the Social Media Mining for Health (SMM4H)-2017 shared task. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(10):1274–83.

Chee BW, Berlin R, Schatz B. Predicting adverse drug events from personal health messages. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. American Medical Informatics Association, 2011. p. 217.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was funded by the AAP-2013-052 grant from the French agency for drug safety, Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé (ANSM), through the Vigi4Med research project, and Convention no 2016S076 through the PHARES project. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the ANSM.

Conflict of interest

Bissan Audeh, Florelle Bellet, Marie-Noëlle Beyens, Agnès Lillo-Le Louët, and Cédric Bousquet have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Audeh, B., Bellet, F., Beyens, MN. et al. Use of Social Media for Pharmacovigilance Activities: Key Findings and Recommendations from the Vigi4Med Project. Drug Saf 43, 835–851 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-00951-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-00951-2