Abstract

Background

Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually considered safe to use in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), there are mixed data about their effectiveness, and only a few investigations have led to a total improvement of depressive symptoms in patients with PD.

Objectives

We aimed to conduct a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of all studies that investigated the effectiveness of SSRIs in treating depression in the context of PD.

Methods

From its commencement to June 2024, the databases of MEDLINE via PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar were electronically searched for the relevant papers. All full-text journal articles assessing the effectiveness of SSRIs in treating depression in patients with PD were included. The tool developed by the Cochrane Collaboration was utilized to evaluate the bias risk. Data were analyzed utilizing a pair-wise comparison meta-analysis using the standardized mean difference.

Results

A total of 19 articles and 22 separate interventions were included. We found that SSRI treatment attenuated depression in patients with PD (1.242 standardized mean difference, 95% confidence interval 0.956, 1.529, p < 0.001). The general heterogeneity of the studies was medium (ϰ2 = 72.818, T2 = 0.317, df = 21, I2 = 71.15%, p < 0.001). The funnel plot was reasonably symmetrical. However, three studies were trimmed to the left of the mean. Begg’s test (p = 0.080), Egger’s test (p = 0.121), and funnel plot showed no significant risk of publication bias. The meta-regression showed that the treatment effect increased as a function of paroxetine treatment duration (slope p = 0.001) but decreased as a function of sertraline treatment duration (slope p = 0.019).

Conclusions

There are few controlled antidepressant trials on the PD population, even though patients with PD frequently experience depression and use antidepressants. Clinical studies that are larger and better structured are needed in the future to determine if antidepressants are useful for treating patients with PD with depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment attenuates depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. |

The medium heterogeneity of the studies regarding the effects of SSRIs in PD-induced depression highlights the need for well-designed clinical trials. |

1 Introduction

Over 1% of the aged population in the world has Parkinson’s disease (PD), which is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s disease [1]. Although PD is typically thought of as a movement disorder, patients with this disorder also experience a wide range of non-motor symptoms. Depression is one of the most prevalent neuropsychiatric manifestations in PD, affecting about 35% of patients [2]. Patients with PD experience depression more frequently than the general senior population or those with other chronic and severe conditions [3].

Parkinson’s disease-induced depression is shown to be strongly linked to a longer illness duration, more severe motor symptoms, levodopa usage, female sex, a history of anxiety and/or depression, a family history of depression, lower functioning in activities of daily living, and a worse cognitive status [4]. Uncertainty surrounds the pathogenesis of depression in PD [5]. Several brain deficits known to have a role in the etiology of PD, such as monoaminergic impairments and lesions of frontal-subcortical circuits, may also be linked to depression [6]. In addition, depression in patients with PD receiving long-term dopamine replacement therapy may worsen or emerge because of decreased levels of norepinephrine and serotonin when the neurons are appropriated by dopaminergic processes [7].

Despite being widespread among patients with PD, depression frequently goes undiagnosed and untreated. In one study, it was discovered that depression affected 27.6% of newly diagnosed patients with PD, but only 40% of them were receiving treatment or evaluation for it [8]. Both medication and mental health interventions can enhance the quality of life and motor symptom control in patients with PD with depression [9]. However, unlike patients with major depressive disorder, antidepressant use in adults with PD is not as standardized [10]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), for example, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram, are the most commonly used class of medication in patients with PD with depression. SSRIs are typically used as first-line medications to treat patients with depression, independent of a concomitant diagnosis of PD, thanks to their safety in overdose and relative tolerability [5]. Although SSRIs are usually considered safe to use in patients with PD, there are mixed data about their effectiveness [11, 12]. The use of SSRI medications in PD has been particularly studied in several randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, only a few of these investigations led to a significant improvement in depressive symptoms in patients with PD [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. It is assumed that due to various study designs, sample sizes, depression assessment systems, and other considerations, the efficacy of these pharmaceutical therapies for patients with PD with depression has been the subject of numerous conflicting findings. Therefore, the objective of this article was to conduct a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of all studies that investigated the effectiveness of SSRIs in treating depression in the context of PD.

2 Methods

2.1 Search Strategy

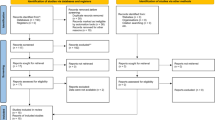

A meta-analysis and systematic review of SSRI treatment for patients with PD with depression was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [20]. An electronic search was conducted in MEDLINE via PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Google Scholar to find pertinent material written before June 2024. The search was performed using the keywords “Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors,” “Parkinson’s disease,” and “major depressive disorder” in the following format: (((((Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors [Title/Abstract]) OR (SSRI[Title/Abstract])) AND (depression [Title/Abstract])) OR (major depressive disorder [Title/Abstract])) OR (MDD[Title/Abstract])) AND (Parkinson’s disease [Title/Abstract]). The references of published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, network meta-analyses, and trials were manually searched.

2.2 Study Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients diagnosed with idiopathic PD who concomitantly had major depression identified and assessed using Beck’s Depression Inventory, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, or Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale depression items. Major or minor depressive disorder was diagnosed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition [16, 17, 21, 22] or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition Revised criteria [18, 23]. For inclusion, these patients should also be receiving SSRI treatment. Both RCTs and before/after (prospective cohorts that compare the effects of a medication before and after administration) studies were included in this analysis. Studies written in languages other than English were also included. Trials that used medications other than SSRIs such as serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or non-pharmacological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy were excluded from this study. Studies on animals (in vivo) and cell lines (in vitro), juvenile PD, and atypical parkinsonism were also not included. In addition, non-comparative investigations, case reports, meta-analyses, and reviews were excluded.

2.3 Data Extraction

Two investigators conducted an independent review to retrieve the data using a set procedure. Discussions with a third senior reviewer helped to settle disputes. Information about the sample size in each arm, the SSRI regimen utilized (dosage and treatment duration), the mean age and gender of patients, the duration of PD, and details about the study design (randomization, allocation concealment, description of withdrawals per arm, and blinding) as well as the names of the authors, the year of publication, and the name of the journal were extracted from the included studies. The primary outcome was the effects of SSRI treatment on depression scores in patients with PD.

2.4 Quality Appraisal

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the risk of bias assessment tool developed by the Cochrane Collaboration. Allocation concealment, selective result reporting, participant blinding, outcome assessor masking, allocation sequence generation, incomplete follow-up, and other possible sources of bias are among the elements of this instrument. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers who carried out the evaluation were reviewed by a senior author. The likelihood of bias was rated as low, uncertain, or high for each component. The reviewer assigned the study to one of the low-bias or high-bias categories, depending on whether they could find information on all the factors included in the tool or none at all. The risk of bias was deemed uncertain if the reviewer’s information was incomplete or uncertain [24].

2.5 Statistics

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed via the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2.0 Software. The means of the groups (placebo vs SSRIs) in each publication were compared using the standardized mean difference (SMD). Using the I2 statistic, the data’s heterogeneity was calculated, and values of 25%, 50%, or 75% were regarded as low, medium, and high, respectively. Funnel plots and trim-and-fill analyses were used to evaluate publication bias. A cumulative impact across outcomes was estimated while simultaneously avoiding bias when a publication included data on more than one outcome, conducted on the same subjects [25]. Multiple results provided for a single domain mean were calculated as follows:

where Y represents the mean of the effect sizes from various outcomes, and m is the number of means. However, we calculated the total variance of these means as follows:

where m is the formula’s number of variances and V and var stands for variance. p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant in each analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Study Characteristics

A total of 19 articles and 22 separate interventions were included in this meta-analysis to analyze the effects of SSRIs on depression in patients with PD. The PRISMA flowchart for study inclusion procedure is presented in Fig. 1 and the detailed study characteristics and demographic data are presented in Table 1. A total of 430 patients with PD with depression were analyzed in this meta-analysis. Seven publications were RCTs and 12 studies were prospective cohorts with a before/after design. Escitalopram, citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline were used in one, four, seven, five, and five studies, respectively. SSRI treatment attenuated depressive symptoms in the majority of the included studies. As the heterogeneity of the included studies was quite substantial (I2 >50%), the random-effects model was applied to analyze the data emerging from interventions [26].

3.2 Effect of SSRIs on Depression

3.2.1 Overall Effect

In general, we found that SSRI treatment attenuated depression in patients with PD (1.242 SMD, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.956, 1.529, p < 0.001) [Fig. 2]. We showed that the general heterogeneity of the studies was medium (ϰ2 = 72.818, T2 = 0.317, d.f. = 21, I2 = 71.15%, p < 0.001).

Forest plot of the standardized mean difference for effect size for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor effects on depression symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The green square shows the overall pooled effect and red squares show the pooled effect for each subgroup of study. Black squares indicate the standardized mean difference in each study. Horizontal lines represent a 95% confidence interval (CI). Std diff standardized difference

3.2.2 Individual Antidepressants

Four studies assessed the effects of citalopram on depression in patients with PD [13, 18, 27, 28]. A quantitative synthesis revealed significant positive effects of citalopram on attenuation of depression in patients with PD (1.514 SMD, 95% CI 0.510, 2.518, p < 0.001) [Fig. 2]. Here, we found that the general heterogeneity of the studies was high (ϰ2 = 17.884, T2 = 0.868, df = 3, I2 = 83.22%, p < 0.001).

One study showed that escitalopram has positive effects on attenuating depression in patients with PD (1.918 SMD, 95% CI 0.951, 2.885, p < 0.001) [29]. Seven studies evaluated the effects of fluoxetine on depression in patients with PD [16, 22, 28, 30,31,32]. A meta-analysis showed significant positive effects of fluoxetine on attenuation of depression in patients with PD (1.133 SMD, 95% CI 0.607, 1.659, p < 0.001) [Fig. 2]. Here, we found that the general heterogeneity of the studies was medium (ϰ2 = 17.806, T2 = 0.318, df = 6, I2 = 66.30%, p < 0.001).

We found five studies that used paroxetine as a treatment for depression in patients with PD [15, 19, 33,34,35]. We found significant positive effects of paroxetine on attenuation of depression in patients with PD (1.098 SMD, 95% CI 0.656, 1.541, p < 0.001) [Fig. 2]. Here, we found that the general heterogeneity of the studies was medium (ϰ2 = 13.700, T2 = 0.177, df = 4, I2 = 70.80%, p < 0.001).

The remaining five studies assessed the effects of sertraline administration on patients with PD [14, 17, 21, 23, 28]. Analysis revealed significant positive effects of sertraline on attenuation of depression in patients with PD (1.340 SMD, 95% CI 0.494, 2.185, p < 0.001) [Fig. 2]. Here, we found that the general heterogeneity of the studies was high (ϰ2 = 19.920, T2= 0.707, df = 4, I2 = 79.92%, p < 0.001).

3.3 Leave-One-Out Sensitivity Analysis

An iterative leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed, deleting one study at a time, and recalculating the summary SMD, to assess the robustness of the association results. This analysis demonstrated that the results were stable, indicating that the exclusion of any one study would not have a substantial impact on the general findings of this study. In other words, this suggests that it is unlikely that a single study could significantly distort or push the SMD in either way (Fig. 3).

3.4 Publication Bias and Study Quality Appraisal

For the study quality appraisal, the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was used. All the papers were published in peer-reviewed journals. The findings revealed that there was 0% selective and incomplete outcome data reporting (reporting bias). However, 15 studies did not observe random sequence generation, six studies did not perform allocation concealment, nine citations did not blind the participants and staff, and six studies did not perform a blinding of outcome assessment. These indicate that the included studies are generally of medium quality (Fig. 4). Publication bias was assessed using funnel plot and trim-and-fill analysis. The funnel plot was reasonably symmetrical. However, three studies were trimmed to the left of the mean. Begg’s test (p = 0.080), Egger’s test (p = 0.121), and funnel plot showed no significant risk of publication bias (Fig. 5).

3.5 Meta-Regression and Moderators’ Analysis

A meta-regression showed that the treatment effect increased as a function of paroxetine treatment duration [point estimate ± standard error = 0.068 ±0.021, Z value = 3.128 (0.025, 0.110) slope p = 0.001] but decreased as a function of sertraline treatment duration [point estimate ± standard error = − 0.068 ± 0.029, Z value = − 2.335 (− 0.126, − 0.011) slope p = 0.019]. Other analyses were not statistically significant (Fig. 6).

4 Discussion

The findings of this study revealed a significant effect of SSRIs in total and individually on attenuating depressive symptoms in patients with PD with varying degrees of depression. The heterogeneity of the included studies was found to be medium. This study did not reveal a significant publication bias across the citations included. Nevertheless, the quality appraisal of these studies showed their low-to-medium quality.

The most widely used antidepressants in patients with PD with the ability to specifically affect the serotonergic system are SSRIs [5]. Around 63% of the antidepressant prescriptions in the USA for the treatment of depression in PD are SSRIs, and just 7% are TCAs [36]. According to the Parkinson’s disease study group, some patients with PD use antidepressants for the alleviation of depression symptoms, and almost half of the physicians regard SSRIs as the first-line pharmacologic therapy in patients with PD with signs of major depressive disorder [37,38,39]. Our results revealed that SSRIs were effective drugs for the treatment of depression in PD in a conventional pairwise comparison. In line with that, Antonini et al. showed that SSRIs (sertraline) and not TCAs (amitriptyline) were able to exert a significant benefit on quality of life (Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire [PDQ-39] scale; mobility, activities of daily living, and stigma) [17]. Similarly, Fregni et al. found that SSRI use was associated with improved activities of daily living [30]. Our findings regarding the efficacy of SSRIs in PD-induced depression are in line with those of other neurodegenerative disorders. In a recent meta-analysis by Zang et al., it was shown that depression symptoms were alleviated in patients with Alzheimer’s disease who used SSRIs (0.905 SMD, 95% CI 0.689, 1.121, p < 0.001). Escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline, when taken separately from other SSRIs, substantially reduced depression symptoms in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (0.813 SMD, 95% CI 0.207, 1.419, p = 0.009, 1.244 SMD, 95% CI 0.939, 1.548, p < 0.001, and 0.818 SMD, 95% CI 0.274, 1.362, p < 0.001) [40]. However, these findings are not universal. Other clinical trials suggested that SSRIs might not be as useful as neurologists and psychiatrists had previously believed [15, 41]. In a meta-analysis, Skapinakis et al. found that the effectiveness of SSRIs in treating depression in the setting of PD is yet unknown. According to the findings of their investigation, the authors could not rule out the potential that SSRIs might eventually provide evidence of efficacy, particularly for severe or extremely severe depression [42]. The evidence emerging from this meta-analysis was not, however, robust, as the number of included studies was too low (n = 4) [42].

It was intriguing to see that, in contrast to sertraline, the effect of paroxetine increased with treatment duration. According to a meta-analysis by Jakubovski et al., the SMD of improvement in depressive symptoms for all SSRIs declines with time. However, the decline is more noticeable at lower doses than at larger doses [43]. The observed increase in the effect of paroxetine with a longer treatment duration, contrasting with the general trend of declining SSRI efficacy over time, could be due to several factors. The unique pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of paroxetine might result in a delayed but sustained therapeutic effect [44]. Differences in patient adherence and tolerability, with paroxetine being better tolerated by some, might lead to longer treatment durations and more pronounced effects. For example, sexual dysfunction is more common with sertraline [45]. Additionally, paroxetine might be more frequently prescribed at higher doses, enhancing its efficacy. Moreover, variability in individual patient responses and differences in study designs and populations included in the meta-analysis might contribute to this unique trend. These factors collectively could explain why the effects of paroxetine increase with prolonged treatment, unlike other SSRIs.

The finding that the SSRI dose did not affect the main outcome in the study, as confirmed by a moderator analysis and meta-regression, could have several explanations. First, there may be a plateau effect where increasing the dose beyond a certain point does not significantly enhance therapeutic benefits, possibly owing to receptor saturation or the maximum achievable efficacy being reached [46]. Second, individual differences in metabolism and receptor sensitivity among patients can lead to variability in optimal dosing, making it challenging to observe a clear dose–response relationship in a meta-analysis. Additionally, the therapeutic window for SSRIs might be relatively narrow, with most effective doses falling within a specific range that minimizes the impact of dose variations [46]. Furthermore, side effects at higher doses could lead to decreased adherence or discontinuation, counteracting potential dose-related benefits. Last, the methodological limitations and variations in study designs, patient populations, and dosing regimens in the included studies might obscure the dose–response relationship. These factors together could explain why the SSRI dose did not significantly affect the main outcome of this study.

In this study, the safety profile of SSRIs was not assessed as the number of studies reporting drug-related reactions and adverse effects was low. Some of the side effects that were reported in these studies were anxiety and palpitation (citalopram) [27], sexual dysfunction (paroxetine) [19], gastrointestinal symptoms (constipation or diarrhea; paroxetine) [39], worsening PD symptoms (paroxetine) [35], worsening baseline nausea and confusion (escitalopram, paroxetine) [29, 34], and flushing (citalopram) [18]. However, even with all of these side effects, the safety profile of SSRIs and comparatively minimal adverse effects with a comparable drop-out rate are a big advantage over other antidepressants such as TCAs [42, 47]. As an example, TCAs exacerbated autonomic phenomena and neuropsychiatric features of PD such as cognitive impairment, visual hallucinations, and delusional thought disorder because of their anticholinergic properties [48]. In tandem with that, Dell’Agnello et al. [28], Kostic et al. [31], and Rampello et al. [27] showed that SSRIs do not exacerbate extrapyramidal symptoms when used as a treatment for depression in PD. In addition, it was shown that SSRI treatment either caused no significant change in motor symptoms and psychomotor speed [29] or improved the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale and motor scores in patients with PD [19]. However, there is concern over the use of SSRIs in depression in patients with PD because of their effects on apathy. In a retrospective review study, Zahodne et al. showed that patients who use SSRIs (but not other antidepressants) for this purpose may experience great degrees of apathy compared with others [49]. This, nevertheless, was contradicted by the findings of the Takahashi et al. study, which showed no changes in apathy scores (p = 0.054) after SSRI use for the treatment of depression in PD [34].

Our findings regarding the efficacy of SSRIs for the treatment of depression in PD are consistent with prior trials and meta-analyses [50, 51]. However, compared with the Wang et al. study [50], our meta-analysis has a focused scope, which provides detailed insights into the effectiveness of SSRIs and their differential impact based on treatment duration. This specificity can aid clinicians in selecting and managing SSRI treatment more effectively. Additionally, the rigorous assessment of publication bias and heterogeneity enhances the credibility of its conclusions. However, the broader approach of the former meta-analysis [47] offers a more comprehensive understanding of multiple antidepressants, which is beneficial for comparing different treatment options. These studies complement each other by providing a broad overview and a detailed focus on SSRIs, respectively, enriching the evidence base for treating depression in PD.

The limited sample size for the trials is the primary drawback of this meta-analysis. The average study period was also short, and there was no further follow-up to prevent extrapolating long-term efficacy. Additionally, patients were often between the ages of 60 and 70 years, which effectively excluded patients who were much older and may have been more incapacitated, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, a number of studies had no data on allocation concealment and random sequence generation, which have an influence on research quality. Furthermore, the methods for diagnosing depression varied greatly. The existing depression measures differ in terms of material that addresses somatic symptoms and were not created particularly for PD. The accuracy of diagnosis can be impacted by the overlap between PD and depressive symptoms, especially when cut-offs are applied. Further, the study participants were not typical of the patients actually encountered in clinical practice. Patients with dementia, significant motor fluctuations, concurrent medical problems, and signs of psychotic depression were often excluded from studies. As a result, our findings should not be applied to patients of these sorts. Another main limitation of this study was many of the included trials were prospective cohorts and were not RCTs. This limited our ability to compare the findings in the SSRI group with those of the placebo group.

5 Conclusions

More frequently than any other type of antidepressants, SSRIs are given for depression, and this is also true for depression in the setting of PD. Our results supported the idea that SSRI treatment is effective in the alleviation of depression symptoms in patients with PD. Unfortunately, even though patients with PD frequently experience depression and use antidepressants, there are few controlled antidepressant trials in this population. For future research, larger and more well-designed clinical studies on the effectiveness of antidepressants on patients with PD who are experiencing depression are required.

References

de Rijk MC, Launer LJ, Berger K, Breteler MM, Dartigues JF, Baldereschi M, et al. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology. 2000;54:S21–3.

Aarsland D, Påhlhagen S, Ballard CG, Ehrt U, Svenningsson P. Depression in Parkinson disease: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;8:35–47.

Nilsson FM, Kessing LV, Sørensen TM, Andersen PK, Bolwig TG. Major depressive disorder in Parkinson’s disease: a register-based study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:202–11.

Leentjens AF, Moonen AJ, Dujardin K, Marsh L, Martinez-Martin P, Richard IH, et al. Modeling depression in Parkinson disease: disease-specific and nonspecific risk factors. Neurology. 2013;81:1036–43.

Ryan M, Eatmon CV, Slevin JT. Drug treatment strategies for depression in Parkinson disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:1351–63.

Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055–66.

Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Angoa-Perez M, Kuhn DM, Bishop C. Potential mechanisms underlying anxiety and depression in Parkinson’s disease: consequences of l-DOPA treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:556–64.

Ravina B, Camicioli R, Como PG, Marsh L, Jankovic J, Weintraub D, et al. The impact of depressive symptoms in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;69:342–7.

DeMarco EC, Zhang Z, Al-Hakeem H, Hinyard L. Depression after Parkinson’s disease: treated differently or not at all? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/08919887221090217.

Pontone GM, Mills KA. Optimal treatment of depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29:530–40.

Mills KA, Greene MC, Dezube R, Goodson C, Karmarkar T, Pontone GM. Efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:642–51.

Starkstein SE, Brockman S. Management of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2017;4:470–7.

Devos D, Dujardin K, Poirot I, Moreau C, Cottencin O, Thomas P, et al. Comparison of desipramine and citalopram treatments for depression in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2008;23:850–7.

Leentjens AF, Vreeling FW, Luijckx GJ, Verhey FR. SSRIs in the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:552–4.

Menza M, Dobkin RD, Marin H, Mark MH, Gara M, Buyske S, et al. A controlled trial of antidepressants in patients with Parkinson disease and depression. Neurology. 2009;72:886–92.

Avila A, Cardona X, Martin-Baranera M, Maho P, Sastre F, Bello J. Does nefazodone improve both depression and Parkinson disease? A pilot randomized trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:509–13.

Antonini A, Tesei S, Zecchinelli A, Barone P, De Gaspari D, Canesi M, et al. Randomized study of sertraline and low-dose amitriptyline in patients with Parkinson’s disease and depression: effect on quality of life. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1119–22.

Wermuth L, Sørensen P, Timm S, Christensen B, Utzon N, Boas J, et al. Depression in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease treated with citalopram: a placebo-controlled trial. Nord J Psychiatry. 1998;52:163–9.

Richard IH, McDermott MP, Kurlan R, Lyness JM, Como PG, Pearson N, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1229–36.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6: e1000097.

Barone P, Scarzella L, Marconi R, Antonini A, Morgante L, Bracco F, et al. Pramipexole versus sertraline in the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a national multicenter parallel-group randomized study. J Neurol. 2006;253:601–7.

Boggio PS, Fregni F, Bermpohl F, Mansur CG, Rosa M, Rumi DO, et al. Effect of repetitive TMS and fluoxetine on cognitive function in patients with Parkinson’s disease and concurrent depression. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1178–84.

Hauser RA, Zesiewicz TA. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1997;12:756–9.

Green S, Higgins P, Alderson P, Clarke M, Mulrow D, Oxman D. Cochrane handbook: Cochrane reviews. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handb Syst Rev Interv. 2011;1:3–10.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. New York: Wiley; 2021.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:97–111.

Rampello L, Chiechio S, Raffaele R, Vecchio I, Nicoletti F. The SSRI, citalopram, improves bradykinesia in patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with l-dopa. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25:21–4.

Dell’Agnello G, Ceravolo R, Nuti A, Bellini G, Piccinni A, D’Avino C, et al. SSRIs do not worsen Parkinson’s disease: evidence from an open-label, prospective study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24:221–7.

Weintraub D, Taraborelli D, Morales KH, Duda JE, Katz IR, Stern MB. Escitalopram for major depression in Parkinson’s disease: an open-label, flexible-dosage study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:377–83.

Fregni F, Santos CM, Myczkowski ML, Rigolino R, Gallucci-Neto J, Barbosa ER, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is as effective as fluoxetine in the treatment of depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1171–4.

Kostić V, Dzoljić E, Todorović Z, Mijajlović M, Svetel M, Stefanova E, et al. Fluoxetine does not impair motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease: correlation between mood and motor functions with plasma concentrations of fluoxetine/norfluoxetine. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2012;69:1067–75.

Serrano-Dueñas M. A comparison between low doses of amitriptyline and low doses of fluoxetin used in the control of depression in patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Rev Neurol. 2002;35:1010–4.

Ceravolo R, Nuti A, Piccinni A, Dell’Agnello G, Bellini G, Gambaccini G, et al. Paroxetine in Parkinson’s disease: effects on motor and depressive symptoms. Neurology. 2000;55:1216–8.

Takahashi M, Tabu H, Ozaki A, Hamano T, Takeshima T. Antidepressants for depression, apathy, and gait instability in Parkinson’s disease: a multicenter randomized study. Intern Med. 2019;58:361–8.

Tesei S, Antonini A, Canesi M, Zecchinelli A, Mariani CB, Pezzoli G. Tolerability of paroxetine in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective study. Mov Disord. 2000;15:986–9.

Chen P, Kales HC, Weintraub D, Blow FC, Jiang L, Mellow AM. Antidepressant treatment of veterans with Parkinson’s disease and depression: analysis of a national sample. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20:161–5.

Farajdokht F, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Majdi A, Pashazadeh F, Vatandoust SM, Ziaee M, et al. Serotonergic system modulation holds promise for l-DOPA-induced dyskinesias in hemiparkinsonian rats: a systematic review. EXCLI J. 2020;19:268–95.

Mueller C, Rajkumar AP, Wan YM, Velayudhan L, Ffytche D, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Assessment and management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:621–35.

Richard IH, Kurlan R. A survey of antidepressant drug use in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson Study Group. Neurology. 1997;49:1168–70.

Zhang J, Zheng X, Zhao Z. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy outcomes of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression in Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2023;23:210.

Okun MS, Fernandez HH. Will tricyclic antidepressants make a comeback for depressed Parkinson disease patients? Neurology. 2009;72:868–9.

Skapinakis P, Bakola E, Salanti G, Lewis G, Kyritsis AP, Mavreas V. Efficacy and acceptability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:49.

Jakubovski E, Varigonda AL, Freemantle N, Taylor MJ, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: dose–response relationship of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:174–83.

Bourin M, Chue P, Guillon Y. Paroxetine: a review. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7:25–47.

Devane CL. Comparative safety and tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(Suppl. 3):S185–93.

Sørensen A, Ruhé HG, Munkholm K. The relationship between dose and serotonin transporter occupancy of antidepressants—a systematic review. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:192–201.

Bomasang-Layno E, Fadlon I, Murray AN, Himelhoch S. Antidepressive treatments for Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21:833–42 (discussion 833).

Gallagher DA, Schrag A. Psychosis, apathy, depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:581–9.

Zahodne LB, Bernal-Pacheco O, Bowers D, Ward H, Oyama G, Limotai N, et al. Are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors associated with greater apathy in Parkinson’s disease? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24:326–30.

Wang XL, Feng ST, Wang YT, Chen B, Wang ZZ, Chen NH, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for Parkinson’s disease with depression: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2022;927: 175070.

Qiu BY, Qiao JX, Yong J. Meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in the efficacy and safety of anti-depression therapy in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13:1213–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No external funding was received to conduct this systematic review/meta-analysis.

Conflicts of interest

Renjie Gao, Panpan Zhao, and Kai Yan have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The public datasets used in this study are available. The other data supporting this study could be requested from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

RG: formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing of the original draft; PZ: data curation, writing of the original draft (supporting); KY: project administration, supervision, writing, review, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, R., Zhao, P. & Yan, K. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for the Treatment of Depression in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Drug Investig 44, 459–469 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-024-01378-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-024-01378-8