Abstract

Dulaglutide (Trulicity™) is a once-weekly subcutaneously administered glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist produced by recombinant DNA technology and approved in numerous countries as an adjunct to diet and exercise for the treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). In randomized controlled trials in patients with T2DM, dulaglutide monotherapy was noninferior to once-daily subcutaneous liraglutide monotherapy and significantly more effective than oral metformin monotherapy in improving glycemic control at 26 weeks. When used in combination with other agents (including metformin, metformin and a sulfonylurea, metformin and oral pioglitazone, and prandial insulin ± metformin), dulaglutide was noninferior to once-daily liraglutide and significantly more effective than once-daily oral sitagliptin, twice-daily subcutaneous exenatide, and once-daily subcutaneous insulin glargine in terms of improvements in glycated hemoglobin from baseline at 26 or 52 weeks, in trials of 26–104 weeks’ duration. Moreover, dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly, but not 0.75 mg once weekly, was associated with consistent reductions form baseline in bodyweight. Improvements in glycemic control and bodyweight were maintained during long-term treatment (up to 2 years). Dulaglutide was generally well tolerated, with a low inherent risk of hypoglycemia. The most frequently reported adverse events in clinical trials were gastrointestinal-related (e.g., nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea). Thus, dulaglutide is a useful option for the treatment of adult patients with T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

Convenient once-weekly regimen, with an easy-to-use, single-dose pen |

Significantly improves glycemic control compared with metformin when used as monotherapy |

Significantly improves glycemic control compared with sitagliptin, exenatide twice daily, or insulin glargine when used as add-on therapy |

Noninferior glycemic control to once-daily liraglutide both as monotherapy and when used as add-on to metformin |

Generally improves bodyweight and surrogate measures of β-cell function |

Improvements in glycemic control and bodyweight are maintained over the long-term (≤2 years) |

Generally well tolerated, with a low intrinsic risk of hypoglycemia |

1 Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is one of the world’s most widespread chronic conditions, with a global prevalence of 387 million in 2014, which is expected to rise to 592 million by 2035 [1]. The disease is commonly managed through multi-modal strategies, including diet and exercise, with a key focus on glycemic control [2, 3]. Diabetes guidelines and organizations recommend the individualization of both glycemic targets and treatment strategies, which have been made possible by the availability of several classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that have different but complementary mechanisms of action, and different safety profiles, tendencies for drug–drug interactions, and routes of administration [2, 3].

Incretins, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, are gut-derived hormones that are secreted in response to nutrient ingestion [4]. GLP-1, a 30-amino acid peptide hormone, is produced in intestinal epithelial endocrine L-cells and when released enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic islet β-cells (‘incretin effect’) [4]. Incretin-based therapies, such as the injectable GLP-1 receptor agonists and orally administered dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, are increasingly being used for the treatment of T2DM [4, 5].

Dulaglutide (Trulicity™), a once-weekly, recombinant human GLP-1 receptor agonist, has recently been approved in several countries for the treatment of T2DM [6–8]. This article provides a narrative review of the clinical use of subcutaneous (sc) dulaglutide in adult patients with inadequately controlled T2DM and overviews its pharmacological properties.

2 Pharmacodynamic Properties of Dulaglutide

Dulaglutide is a recombinant fusion protein consisting of two identical disulphide-linked chains, each with a N-terminal GLP-1 analog sequence that is covalently linked to the Fc section of modified human immunoglobulin G4 heavy chain (IgG4 Fc) [6, 7, 9]. The GLP-1 analog portion of dulaglutide has 90 % homology to the amino acid sequence of endogenous GLP-1 (fragment 7–37), but with structural modifications for protection from DPP-4 inactivation [6, 7, 9]. Because of its fusion to IgG4 Fc and DPP-4 resistance, dulaglutide has a longer half-life than native GLP-1 [6, 7, 9].

Dulaglutide binds to the GLP-1 receptor with high affinity in vitro and exhibits several antihyperglycemic actions of native GLP-1 [6, 7, 9, 10]. It enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion from β-cells, by increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate, and suppresses elevated postprandial glucagon secretion from α-cells [6, 7, 9]. Additionally, dulaglutide promotes satiety and reduces food intake by decreasing appetite [6, 7, 9].

Insulin is released in a biphasic manner in response to glucose, with the first phase insulin response characteristically absent in patients with T2DM [11]. In a phase I trial, dulaglutide restored first-phase insulin secretion and improved second-phase insulin secretion in patients with T2DM [6, 7].

Dulaglutide slows gastric emptying; the greatest delay occurs after the first dose and diminishes with subsequent doses [6, 7, 12].

In patients with T2DM, dulaglutide dose-dependently reduced glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and postprandial plasma glucose (PPG) excursions [13–17]. Additionally, dulaglutide increased insulin secretion [14] and reduced postprandial glucagon secretion [18]. Improvements in glycemic control and other efficacy outcomes in adults with T2DM receiving dulaglutide as monotherapy or add-on therapy in large phase III trials [18–25] are discussed in Sect. 4.

Once-weekly dulaglutide was associated with significantly (p < 0.05) larger dose-dependent increases from baseline in β-cell function, evaluated using the homeostasis model assessment for β-cell function (HOMA-%β), than placebo after 12 [15] and 16 [13] weeks’ treatment in patients with T2DM. Moreover, increases from baseline in HOMA-%β were significantly (p < 0.001) greater in patients receiving dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly monotherapy than in patients receiving metformin monotherapy at 26 and 52 weeks in AWARD-3 [18]. In combination with metformin with or without pioglitazone, add-on dulaglutide increased HOMA-%β to a significantly (p < 0.001) greater extent than add-on exenatide twice daily at 26 weeks (dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly) and 52 weeks (dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly) in AWARD-1 [21], and add-on sitagliptin once daily at 52 [19] and 104 [26] weeks (both dosages) in AWARD-5. Increases in HOMA-%β were not significantly different between patients receiving add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly or add-on liraglutide once daily at 26 weeks in AWARD-6 [20].

Insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, estimated by homeostasis model assessment for insulin sensitivity (HOMA2-%S), was significantly (p ≤ 0.01) lower in dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly groups than in the metformin group at 26 weeks in AWARD-3, suggesting that the predominant glucose-lowering mechanism of dulaglutide relates to enhancement of pancreatic β-cell function [18]. In other trials, there were no significant differences in HOMA2-%S between patients receiving dulaglutide once weekly than those receiving placebo [13, 15], exenatide twice daily [21], or sitagliptin once daily [19] at study end.

The effect of dulaglutide on blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) was evaluated in a 26-week, phase II trial in adults (n = 755) with T2DM (baseline BP range >90/60 to <140/90 mmHg) receiving at least one oral antihyperglycemic drug (OAD) [27]. At 16 weeks, reductions in ambulatory 24-h systolic BP (SBP; primary endpoint) were significantly (p ≤ 0.001) greater with add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly, but not with add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly (noninferior to placebo), than with add-on placebo [27]. Significant reductions in ambulatory 24-h SBP in the dulaglutide 1.5 mg group versus placebo were maintained after 26 weeks (p = 0.002) [27]. At 26 weeks, both dosages of add-on dulaglutide resulted in significantly (p < 0.05) greater improvements in diurnal SBP than placebo, with add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly also significantly (p < 0.05) improving night-time SBP [27]. Dulaglutide was associated with increases in HR (2–4 bpm) [27].

Furthermore, dulaglutide improved other markers of cardiovascular (CV) risk. For instance, dulaglutide reduced bodyweight (Sect. 4) [13–17] and improved some biomarkers of CV risk in patients with T2DM, including total and LDL cholesterol [19, 21], HDL cholesterol [23], triglyceride [21], and C-reactive protein levels [27].

In a thorough corrected QT study, supratherapeutic doses (4 and 7 mg) of dulaglutide did not produce prolongation of the corrected QT interval [7].

3 Pharmacokinetic Properties of Dulaglutide

The pharmacokinetic profile of sc dulaglutide is similar in healthy volunteers to that in patients with T2DM, and did not differ to a clinically meaningful extent when different injection sites were used (upper arm, abdomen, and thigh) [6, 7]. The pharmacokinetics of dulaglutide are best described by a two-compartment model with first-order absorption [28].

Dulaglutide is slowly absorbed, reaching maximum plasma concentrations at steady state within 24–72 h (median 48 h) [6, 7, 28]. With once-weekly sc injections, steady-state plasma concentrations were reached after 2–4 weeks [6, 7, 28]. The accumulation ratio was ≈1.56 following multiple weekly doses of dulaglutide 1.5 mg to steady state [28]. Systemic exposure to dulaglutide was less than dose-proportional across the dose range of 0.05–8 mg [10]. Following a single dose of sc dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg, the mean absolute bioavailability values were 65 and 47 % [6, 7]. At steady state, the mean volumes of distribution were 19.2 and 17.4 L after administration of dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg, respectively [6, 7].

The primary metabolic pathway is presumed to be degradation into its component amino acids by general protein catabolism pathways [6, 7]. At steady state, the mean apparent clearance of dulaglutide was ≈0.1 L/h for both dosages of dulaglutide (0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly) [6, 7]. The elimination half-life of dulaglutide for both doses is ≈5 days, allowing for once weekly administration [6, 7].

Gender, age, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and the presence of renal or hepatic impairment [29] had no clinically relevant effect on the pharmacokinetics of dulaglutide, based on results of population pharmacokinetic analyses [6, 7].

Since dulaglutide slows gastric emptying, it may influence the absorption of orally administered medications [6, 7]. Caution is advised for drugs that require rapid gastrointestinal absorption. Studies have shown no clinically relevant interactions between dulaglutide and paracetamol, atorvastatin, digoxin, lisinopril, metoprolol, S-warfarin, R-warfarin, sitagliptin, or oral contraceptives [6, 7].

4 Therapeutic Efficacy of Dulaglutide

The efficacy of once-weekly sc dulaglutide, as monotherapy (Sect. 4.1) or add-on therapy (Sects. 4.2, 4.3, 4.4), in adults (aged ≥18 years) with inadequately controlled T2DM was assessed in several double-blind [18, 19, 21, 25] or open-label [20, 22–24], phase III trials: the global (AWARD) trials [18–23] and two Japanese trials [24, 25]. Some trial data are available as abstract presentations [30–39]. At baseline, across all AWARD studies, patients had a mean BMI of 31–34 kg/m2, with the mean duration of diabetes ranging from 2.6 (AWARD-3) to 13.0 (AWARD-4) years [18–23], and previous antihyperglycemic treatments reflecting the prespecified inclusion criteria in each study [18–25]. In the Japanese trials, patients had a mean BMI of 26 kg/m2 and the mean duration of diabetes was 6.6 [25] and 8.8 [24] years. In all trials, inadequately controlled T2DM was typically defined as an HbA1c of 7–10 or 7–11 % at baseline [18–25]. The primary efficacy endpoint was the least-squares mean (LSM) change from baseline in HbA1c at week 26 [18, 20, 21, 23–25] or 52 [19, 22] in the intent-to-treat population.

4.1 As Monotherapy

Dulaglutide monotherapy improved glycemic control in the AWARD-3 study [18] and in a Japanese study [25]. In AWARD-3 at week 26, recipients of dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly achieved a significantly greater LSM reduction from baseline in HbA1c than metformin recipients, with significantly more dulaglutide recipients achieving target HbA1c (Table 1) [18]. Fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels were not significantly different between treatment groups (Table 1). Treatment with dulaglutide improved HbA1c regardless of previous treatment (i.e. prior OADs or diet alone) [18] or baseline BMI [37]. Weight loss was observed in all three groups after 26 weeks’ treatment; weight loss was greater in the metformin group than the dulaglutide 0.75 mg group, but not the dulaglutide 1.5 mg group (Table 1) [18]. At 52 weeks, dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly was significantly (p = 0.02) more effective in reducing HbA1c from baseline than metformin, while dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly was noninferior to metformin [18]. The proportion of patients achieving target HbA1c and LSM reductions in FSG levels was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the dulaglutide 1.5 mg group than in the metformin group, while there was no significant difference in these endpoints between the dulaglutide 0.75 mg and metformin groups [18].

In the Japanese trial, dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly was noninferior to, but not superior to, liraglutide 0.9 mg once daily in terms of the LSM reduction from baseline in HbA1c at week 26 (Table 1) [25]. Moreover, dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly significantly improved FPG and significantly more patients achieved HbA1c targets than placebo (Table 1).

4.2 As Add-On Therapy to Metformin

In AWARD-6, add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly was noninferior to, but not superior to, add-on liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily in terms of the LSM reduction from baseline in HbA1c at week 26 in patients with T2DM inadequately controlled by metformin (Table 1) [20]. There were no significant between-group differences with regard to reductions in FSG levels or the proportion of patients achieving target HbA1c (Table 1) [20]. Add-on dulaglutide and add-on liraglutide significantly (p < 0.0001) reduced PPG levels, measured using seven-point SMPG profiles, from baseline at week 26, with no significant difference between groups (−2.56 vs. −2.43 mmol/L) [20]. Add-on liraglutide reduced bodyweight to a significantly greater extent than add-on dulaglutide (Table 1) [20].

In AWARD-5, add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly improved glycemic control to a significantly greater extent than add-on sitagliptin once daily in patients with T2DM inadequately controlled by metformin [19]. LSM changes from baseline in HbA1c at 26 weeks were significantly greater in patients receiving add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg (−1.22 vs. +0.03 %; p < 0.001), 0.75 mg (−1.01 vs. +0.03 %; p < 0.001) and add-on sitagliptin (−0.61 vs. +0.03 %; p < 0.001) than placebo [19]. Additionally, LSM changes from baseline in HbA1c at 26 weeks were significantly (p < 0.001) greater in both add-on dulaglutide groups than in the add-on sitagliptin group [19].

At the primary timepoint of 52 weeks in AWARD-5, both dosages of add-on dulaglutide were associated with significantly greater LSM reductions from baseline in HbA1c (primary endpoint), bodyweight, and FPG than add-on sitagliptin, with significantly more add-on dulaglutide recipients achieving target HbA1c than add-on sitagliptin recipients (Table 1) [19]. A post-hoc analysis revealed that LSM reductions in HbA1c with add-on dulaglutide were consistent regardless of baseline BMI status [37].

Furthermore, add-on dulaglutide produced sustained efficacy over the long-term in AWARD-5, as evidenced by durable HbA1c- and FPG-lowering effects [26]. At 104 weeks, add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly were associated with significantly (p < 0.001) greater LSM reductions from baseline than add-on sitagliptin once daily in HbA1c (−0.71 and −0.99 vs. −0.32 %) and FPG (−1.4 and −2.0 vs. −0.5 mmol/L). Significantly (p < 0.001) more add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg than add-on sitagliptin recipients achieved an HbA1c of <7 % (45 and 54 vs. 31 %) or ≤6.5 % (24 and 39 vs. 14 %) at 104 weeks [26].

Significantly (p < 0.001) greater improvements in bodyweight at 104 weeks were observed in the add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg group than in the add-on sitagliptin group (LSM reduction of 2.88 vs. 1.75 kg), but not in the add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg group (LSM reduction of 2.39 kg) in AWARD-5 [26].

4.3 As Add-On Therapy to Other Oral Antihyperglycemic Drugs (OADs)

In patients receiving maximally tolerated doses of metformin plus pioglitazone, add-on dulaglutide was significantly more effective than add-on exenatide or add-on placebo in improving LSM change in HbA1c from baseline to 26 weeks (primary timepoint) and more patients achieved target HbA1c in the add-on dulaglutide groups (Table 1) in AWARD-1 [21]. Add-on dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly and add-on exenatide twice daily were associated with significantly greater reductions in bodyweight than add-on placebo (Table 1). Bodyweight changes favored add-on exenatide over add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg group (p < 0.05), but there was no significant difference between the add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg and add-on exenatide groups [21]. Post-hoc analyses revealed that LSM reductions in HbA1c with add-on dulaglutide were consistent, regardless of baseline HbA1c [39] or BMI [37].

At 26 weeks, add-on dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly were associated with a significantly (p < 0.001) greater reduction in the mean of all premeal plasma glucose levels, measured using 8-point SMPG profiles than placebo and add-on exenatide twice daily [21]. Patients receiving add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg had a significantly (p = 0.047) greater reduction in the mean of all PPG values than add-on exenatide. Compared with add-on exenatide, add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg was associated with significantly (p < 0.05) greater reductions from baseline in midday meal and evening meal PPG levels. There were no significant between-group differences in LSM reductions in morning meal PPG levels. Add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg and add-on exenatide were associated with significantly (p < 0.01) greater reductions in the mean of all 2-h PPG excursions than placebo; reductions in the mean of all 2-h PPG excursions were significantly (p < 0.001) greater in the add-on exenatide group than in the add-on dulaglutide groups [21].

The significant differences between the add-on dulaglutide groups and the add-on exenatide group for LSM reductions from baseline in HbA1c (p < 0.001), FPG (p ≤ 0.005) at 26 weeks were maintained at 52 weeks [21]. At 52 weeks, there was no significant difference between the add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg and add-on exenatide groups in bodyweight reductions; however, bodyweight changes favored add-on exenatide over add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg group (p < 0.05) [21].

In AWARD-2, in combination with maximally tolerated doses of metformin and glimepiride, add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly was significantly more effective than add-on insulin glargine once daily with regard to the LSM change from baseline in HbA1c at 52 weeks (primary timepoint; Table 1) [22]. Add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly was noninferior to, but not superior to, add-on insulin glargine in terms of reductions from baseline in HbA1c [22]. Post-hoc analyses revealed that LSM reductions in HbA1c with add-on dulaglutide were consistent, regardless of duration of diabetes [38] or baseline BMI [37].

Target HbA1c at week 52 was achieved by significantly more recipients of add-on once-weekly dulaglutide 1.5 mg (<7 and ≤6.5 %) and 0.75 mg (<6.5 % only) than recipients of insulin glargine (Table 1) [22]. Changes in bodyweight significantly favored add-on dulaglutide over add-on insulin glargine (Table 1).

Also at 52 weeks, add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly, but not 0.75 mg once weekly, was associated with significantly (p < 0.05) greater reductions in pre-evening-meal, 2 h post-evening-meal, and bedtime glucose levels (measured using 8-point SMPG profiles) than add-on insulin glargine [22]. Add-on insulin glargine was associated with greater reductions in pre-morning-meal glucose levels than add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg (p ≤ 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively), and greater reductions in glucose levels at 3 am or 5 h after bedtime than dulaglutide 0.75 mg (p ≤ 0.001). There were no significant differences between treatment groups in 2 h post-morning meal, pre-midday meal, 2 h post-midday meal, or mean daily 2-h postprandial 8-point SMPG values [22].

At 78 weeks in AWARD-2, LSM changes in HbA1c, percentages of patients attaining HbA1c targets, and bodyweight reductions still favored add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly over add-on insulin glargine once daily (p < 0.001) [22]. In the add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg group, LSM reductions in HbA1c remained noninferior to add-on insulin glargine and bodyweight reductions remained greater (p < 0.001) than with add-on insulin glargine at 78 weeks; there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients achieving target HbA1c between the treatment groups. LSM reductions in FSG levels were greater in the add-on insulin glargine group than in the add-on dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg groups at 78 weeks (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively) [22].

In Japanese patients with T2DM uncontrolled on sulfonylureas and/or biguanides, add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly was more effective than add-on insulin glargine once daily with regard to the LSM reduction in HbA1c at 26 weeks (Table 1) [24]. Moreover, LSM reductions in HbA1c were significantly greater in the add-on dulaglutide group than add-on insulin glargine group at weeks 8, 14, and 20 (p < 0.001). Bodyweight reductions and the proportion of patients achieving HbA1c targets also favored add-on dulaglutide 0.75 once weekly over add-on insulin glargine (Table 1); however, no significant difference was found for FPG levels [24].

4.4 As Add-On Therapy to Insulin Lispro ± Metformin

In AWARD-4, add-on dulaglutide improved glycemic control in patients inadequately controlled by insulin lispro with or without metformin [23]. After 26 weeks, HbA1c was reduced from baseline to a significantly greater extent with add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly than with add-on insulin glargine (Table 1). Bodyweight reductions also favored add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly over add-on insulin glargine (Table 1). Target HbA1c at week 26 was achieved by significantly more recipients of add-on once-weekly dulaglutide 1.5 mg (<7 and ≤6.5 %) and 0.75 mg (<7 % only) than recipients of insulin glargine (Table 1) [23]. However, insulin glargine was associated with a greater LSM reduction in FSG levels than either dosage of dulaglutide (Table 1) [23]. In post hoc analyses, reductions in HbA1c with add-on dulaglutide were consistent, regardless of baseline HbA1c [36] or BMI [37].

Using 8-point SMPG profiles, there were no significant differences between the add-on dulaglutide groups and the insulin glargine group in the mean daily or day-time mean plasma glucose levels at 26 weeks [23]. Compared with add-on insulin glargine, add-on dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg once weekly were associated with a significantly greater reduction in mean postprandial (p < 0.05 for dulaglutide 1.5 mg) and mean of all 2-h postprandial excursions (p < 0.0001), and a significantly smaller reduction in mean pre-meal (p < 0.01) and mean nocturnal (p < 0.001) glucose levels at 26 weeks [23].

At 52 weeks, all between group differences versus insulin glargine remained significant (p < 0.05), except for the proportion of patients achieving a HbA1c of <7 % in the add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg group, the proportion achieving an HbA1c of ≤6.5 % in both add-on dulaglutide groups, and the mean postprandial plasma glucose level in the add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg group [23].

4.5 Treatment Satisfaction/Health-Related Quality of Life

Dulaglutide, as monotherapy or add-on therapy, improved total treatment satisfaction and decreased perceived frequency of hyperglycemia in AWARD-1 and AWARD-3 [40]. Add-on dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly improved the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) total score and the perceived frequency of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia score from baseline significantly (p < 0.05) more than add-on exenatide twice daily at week 26 and 52 in AWARD-1. In AWARD-3, there were no significant differences between the dulaglutide and metformin monotherapy groups for changes in total DTSQ scores from baseline to week 26 and 52, with significant (p < 0.05) improvements from baseline observed in all groups. Improvements in the perceived hyperglycemia score were significantly (p < 0.05) greater in dulaglutide 1.5 mg recipients than in metformin recipients at 26 and 52 weeks, and in dulaglutide 0.75 mg recipients than metformin recipients at 52 weeks [40].

Weight-related self-perception (IW-SP) total scores were generally improved from baseline to a similar extent in patients receiving dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly, as monotherapy or add-on therapy, compared with metformin monotherapy, add-on exenatide, or add-on liraglutide [30, 32, 33]. However, add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg resulted in significantly (p < 0.05) greater improvements in IW-SP total scores than add-on insulin glargine in AWARD-4 (26 and 52 weeks) [35] and AWARD-2 (52 weeks) [34]. Additionally, improvements in impact of weight on quality of life-lite total scores significantly (p < 0.05) favored add-on dulaglutide over add-on sitagliptin at 78 weeks (dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg) and 104 weeks (dulaglutide 1.5 mg) in AWARD-5 [31].

Although significant improvements from baseline in the ability to perform daily physical activities, as measured by the ability to perform physical activities of daily living (APPADL) questionnaire, were seen in the add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg group in some trials at 26 weeks [32, 34], there were no significant between-group differences in APPADL scores in groups receiving dulaglutide, as monotherapy or add-on therapy, or in groups receiving metformin monotherapy or add-on exenatide, sitagliptin, liraglutide, or insulin glargine in other trials [30–35].

At study end, there were no significant differences in EuroQoL 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) visual analogue scale (VAS) scores or EQ-5D UK population index scores in patients receiving add-on dulaglutide compared with exenatide, sitagliptin, liraglutide, or insulin glargine [30–32, 35]. However, in AWARD-2, improvements in EQ-5D UK population index scores were significantly greater in both add-on dulaglutide groups than in the add-on insulin glargine group at week 52 [34].

5 Tolerability of Dulaglutide

5.1 General Profile

Once-weekly sc dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg were generally well tolerated as monotherapy or as add-on therapy to other antihyperglycemic drugs in clinical trials (≤2 year’s treatment) discussed in Sect. 4. Based on a pooled analysis of six phase II and III trials (≥26 weeks’ duration), the proportion of patients experiencing treatment-emergent adverse events were 74.2, 75.4, and 73.7 % in the dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly (n = 1671), dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly (n = 1671), and comparator groups (n = 1844), respectively [10]. The corresponding incidence of serious adverse events were 8.7, 8.0, and 10.1 %, with hypoglycemia being the most commonly reported serious event [10]. In the dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg groups, 7.7 and 10.4 % of patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events. Twice as many dulaglutide 1.5 mg than 0.75 mg recipients reported nausea as the reason for discontinuation (1.9 vs. 1.0 %) [10].

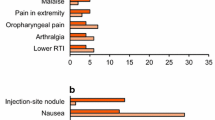

Most treatment-emergent adverse events occurring during dulaglutide therapy were dose-related and gastrointestinal (GI) in nature (Fig. 1), of mild or moderate intensity and resolved after the first few weeks of treatment [6, 7]. The nature and incidence of GI adverse events was generally similar between treatment groups in AWARD-3 (dulaglutide vs. metformin monotherapy) [18], AWARD-6 (add-on dulaglutide vs. add-on liraglutide) [20] and the Japanese monotherapy trial (dulaglutide vs. liraglutide) [25]. In AWARD-5, the incidence of GI adverse events (nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting) and decreased appetite were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in dulaglutide recipients than in sitagliptin recipients at 52 weeks [19]. In AWARD-1, the nature and incidence of GI adverse events was generally similar in the add-on dulaglutide 1.5 mg group to that in the add-on exenatide twice daily group, although nausea, vomiting, and dyspepsia were reported in fewer add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg than add-on exenatide recipients (p < 0.05) [21]. As add-on to metformin and glimepiride, the incidence of diarrhea was significantly higher in the dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg groups than in the insulin glargine group in AWARD-2 at 78 weeks (p < 0.001) [22]. In AWARD-4, as add-on to insulin lispro (±metformin), dulaglutide 1.5 and 0.75 mg once weekly were associated with numerically higher incidence of nausea (26 and 18 vs. 3 %), diarrhea (17 and 16 vs. 6 %), and vomiting (12 and 11 vs. 2 %) than insulin glargine at 52 weeks [23]. In Japanese patients add-on dulaglutide 0.75 mg was associated with a significantly higher incidence of diarrhea (p < 0.001), nausea (p < 0.001), constipation (p < 0.05), and increased lipase levels (p < 0.001) than add-on insulin glargine at 26 weeks [24].

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in ≥5 % of dulaglutide-treated patients (0.75 or 1.5 mg once weekly as monotherapy or add-on therapy) in a pooled analysis of phase II and III trials of ≥26 weeks’ duration [10]. Control arms included treatment with metformin, placebo/sitagliptin or sitagliptin, exenatide, insulin glargine, or placebo URTI upper respiratory tract infection, UTI urinary tract infection *p < 0.001 vs. all-comparator group

5.2 Hypoglycemia

The incidence of documented symptomatic hypoglycemia (plasma glucose ≤70 mg/dL) was generally low (5.9–10.9 %) when once-weekly dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg were used as monotherapy [18, 25] or in combination with metformin alone [19, 20] or metformin and pioglitazone [21] and there were no reports of severe hypoglycemia in the dulaglutide groups. Rates of documented symptomatic hypoglycemia ranged from 0.14 to 0.62 events/patient/year [6].

As expected, documented symptomatic hypoglycemia was more frequent when dulaglutide was used in combination with a sulfonylurea in the presence of metformin (AWARD-2), insulin lispro with and without metformin (AWARD-4) [10], or in Japanese patients with T2DM uncontrolled on sulfonylureas and/or biguanides [24]. When administered with sulfonylureas and/or biguanides, the incidence of documented symptomatic hypoglycemia was ≈40 % (<1 % severe) with add-on dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg (1.67 events/patient/year for both dosages), compared with 51 % in add-on insulin glargine recipients (3.02 events/patient/year) in AWARD-2 [6, 10], and 26 % with add-on dulaglutide 0.75 and 1.5 mg (0.09 events/patient/30 days) versus 48 % with add-on insulin glargine (0.24 events/patient/30 days) in Japanese patients (p < 0.001) [24]. When administered with prandial insulin with or without metformin, the incidence of hypoglycemia was 85.3 and 80.0 % (2.4 and 3.4 % severe) and rates were 35.66 and 31.06 events/patient/year in the once-weekly dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg groups, respectively, compared with 83 % (severe in 5 %) in the insulin glargine group (40.95 events/patient/year) [6, 10].

5.3 Other Adverse Events of Special Interest

As dulaglutide is a therapeutic protein, there is potential for an immune response against the agent [6, 7]. The incidence of dulaglutide anti-drug antibodies (ADA) was low (1.6 %), based on integrated immunogenicity data from four phase II and five phase III trials [41]. In patients who developed ADA, 53 % (0.9 % of the overall population) had dulaglutide-neutralizing antibodies and 56 % (0.9 % of the overall population) developed antibodies against native GLP-1 [7]. Dulaglutide ADA were not detected in any patient who experienced systemic hypersensitivity [41]. The development of ADA does not appear to have a significant effect on changes in HbA1c and was not associated with systemic hypersensitivity adverse events [41].

Three cases of thyroid cancer were reported in dulaglutide-treated patients compared with no cases in comparator groups during the clinical trials, although causality could not be established [10]. One patient developed medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) approximately 1 year after receiving dulaglutide 2.0 mg once weekly for 6 months; however, the patient had a markedly elevated serum calcitonin level at baseline and was positive for a rearranged during transfection proto-oncogene mutation, suggesting that the cancer was pre-existing [19]. Two patients had papillary thyroid cancers while receiving dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly [10].

Pancreatitis is a potential concern for all incretin agents [42]. The incidence of acute pancreatitis during clinical trials was 0.07 % in dulaglutide recipients compared with 0.14 % in placebo recipients and 0.19 % in patients receiving active comparator drugs with or without background therapy [6]. Twelve dulaglutide recipients (3.4 cases/1000 patient-years) were reported by investigators to have acute or chronic pancreatitis compared with three non-incretin recipients (2.7 cases/1000 patient-years) [7, 10]. Five cases in dulaglutide recipients (1.4 cases/1000 patient-years) and one case in non-incretin comparators (0.88 cases/1000 patient-years) were confirmed as pancreatitis [7]. Dulaglutide was associated with mean increases from baseline in pancreatic enzymes (lipase and/or pancreatic amylase) of 11–21 % [6].

Dulaglutide was associated with a mean increase in HR of 2–4 beats per minute; however, the long-term clinical effects of the increase in HR have not been established [6, 7]. Sinus tachycardia, associated with a concomitant increase from baseline in HR of ≥15 beats per minute, was reported in more than twice as many once-weekly dulaglutide 0.75 or 1.5 mg recipients than placebo recipients (1.7 and 2.2 vs. 0.7 %) [6, 7].

In a meta-analysis of phase II and III studies, 26 out of 3,885 (0.67 %) patients who had received dulaglutide and 25 out of 2125 (1.18 %) who had received a comparator experienced at least one CV event (death due to CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina), resulting in a hazard ratio of 0.57 (adjusted 98.2 % CI 0.30–1.10) [43].

There have been postmarketing reports of acute decreases in renal function in patients receiving other incretin-based therapies [44]. An analysis of nine phase II and III studies revealed that rates of acute kidney injury were 3.4, 1.7, and 7.0 events per 1000 patient-years of exposure for dulaglutide, active comparators, or placebo, respectively [44].

6 Dosage and Administration of Dulaglutide

In the EU, dulaglutide is indicated in adults with T2DM as monotherapy when diet and exercise alone do not provide adequate glycemic control in patients for whom the use of metformin is considered inappropriate, or as add-on therapy to other antihyperglycemics including insulin, when these agents, together with diet and exercise, do not provide adequate glycemic control [6]. In the USA, dulaglutide is indicated in adults with T2DM as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control [7].

Dulaglutide is administered subcutaneously (abdomen, thigh, or upper arm) once weekly at any time of the day, without regard to food [6, 7]. In the EU, the initial starting dosage is 0.75 mg once weekly when used as monotherapy and 1.5 mg once weekly when used as add-on therapy (0.75 mg once weekly can be considered in potentially vulnerable populations) [6]. In the USA, the initial starting dosage is 0.75 mg once weekly and may be increased to 1.5 mg once weekly for additional glycemic control [7].

Dulaglutide is not recommended for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, or severe abdominal or intestinal problems (e.g., gastroparesis), or as a first-line therapy for patients who cannot be managed with diet and exercise [6, 7]. As with other GLP-1 agonists, the US prescribing information contains a special warning about a possible risk of thyroid C-cell tumors, including MTC, with dulaglutide, and the drug is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of these tumors and in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 [7].

Local prescribing information should be consulted for detailed information regarding the use of dulaglutide in specific patient populations, contraindications, warnings, and precautions.

7 Place of Dulaglutide in the Management of T2DM

Guidelines recommend an individualized approach to treatment, with metformin and lifestyle modifications as first-line therapy for most patients [2, 3]. If glycemic control is not achieved after ≈3 months, the addition of a sulfonylurea, a thiazolidinedione, a DPP-4 inhibitor, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, a GLP-1 receptor agonist or basal insulin should be considered, initially as a two-drug combination and then as a three-drug combination [2, 3]. There are numerous factors to consider when choosing pharmacologic agents, including the extent of glycemic control, CV risk, effects on bodyweight, potential adverse events, hypoglycemia risk, ease of use, cost, and individual patient preferences [2, 3, 5].

GLP-1 receptor agonists represent a class of injectable antihyperglycemic drugs that are indicated as adjunct therapy to diet and exercise, and have generally been recommended for use as second-line monotherapy or in conjunction with other therapies in dual, triple, or more complex regimens [2]. Dulaglutide is the most recent GLP-1 receptor agonist to be approved (others include exenatide [twice daily or once weekly formulations], once-daily liraglutide, once-daily lixisenatide [currently approved in the EU, but not US], and once-weekly albiglutide) [4].

Dulaglutide lowers both FPG and PPG by activating the GLP-1 receptor resulting in increased insulin release in response to hyperglycemia and decreases glucagon secretion (Sect. 2). An extensive clinical trial program has established the efficacy of once-weekly dulaglutide in patients with T2DM. As monotherapy, dulaglutide was non-inferior to liraglutide once daily and was significantly more effective than metformin in terms of improvements in glycemic control at week 26 (Sect. 4.1). When used in combination with other agents (including metformin, metformin + pioglitazone, sulfonylureas ± biguanides, and prandial insulin ± metformin), dulaglutide was noninferior to liraglutide once daily and was significantly more effective than sitagliptin once daily, exenatide twice daily, and insulin glargine once daily in terms of improvements in HbA1c in clinical trials of 26–104 weeks’ duration (Sects. 4.2, 4.3, 4.4). Moreover, the significant improvements in glycemic control and reductions in bodyweight in favour of add-on dulaglutide versus add-on sitagliptin were sustained for up to 2 years.

Management of comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia is an important part of the treatment of T2DM [2, 3]. While most classes of antihyperglycemics are weight neutral (e.g., DPP-4 inhibitors) or associated with weight gain (e.g., sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, basal insulin), GLP-1 receptor agonists can be associated with weight loss [3]. Indeed, bodyweight reduction with dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly was greater than that with sitagliptin or insulin glargine, was generally similar to that with metformin or twice-daily exenatide, and was less than that with liraglutide. Weight reduction was greater with dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly than insulin glargine and sitagliptin, but less than that seen with metformin or twice-daily exenatide (Sect. 4).

New drugs used in the management of T2DM must be demonstrated to have a satisfactory CV safety profile [45]. Dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly was associated with small reductions in 24-h, daytime and nocturnal SBP, and improvements in some lipid parameters (Sect. 2), but was also associated with dose-dependent increases in HR (Sect. 5). The ongoing phase III, REWIND trial (NCT01394952; n = 9622 enrolled) will further evaluate the CV safety of dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly; it is expected to be completed by April 2019 [46].

There are a dozen different classes of antihyperglycemics available, many of which contain multiple medications [2, 3]. However, some treatment strategies may negatively impact patients’ psychosocial functioning. In order to appreciate the patients’ perspective of treatment effects, patient-reported outcome measures are increasingly included in clinical development programs [47, 48]. Dulaglutide significantly improved various patient-reported outcomes compared with baseline (e.g., treatment satisfaction, perceived current health status, and the ability to perform daily activities) during the AWARD trials (Sect. 4.5).

Dulaglutide was generally well tolerated in the phase III trials, with most treatment-emergent adverse events being of mild to moderate intensity (Sect. 5). As expected for this drug class, the most frequent adverse events were GI disorders, with transient nausea, diarrhea and vomiting being the most common, which were generally reported more frequently in dulaglutide groups than in placebo arms or comparator arms containing sitagliptin or insulin glargine. The incidence of hypoglycemia was generally low across all studies (Sect. 5.2). Unsurprisingly, rates of hypoglycemia with dulaglutide were higher in the trials that included background therapies known to cause hypoglycemia, such as insulin and sulfonylureas.

There is concern around the risk of thyroid cancer associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists [49]. In rodents, GLP-1 stimulates calcitonin secretion and promotes the development of C-cell hyperplasia and MTC, but firm evidence supporting or ruling out this hypothesis in humans is lacking [49, 50]. In a study in non-human primates (male cynomolgus monkeys), dulaglutide did not increase serum calcitonin or affect thyroid weight, histology, C-cell proliferation, or absolute/relative C-cell volume [51]. Across all six AWARD trials, three dulaglutide recipients developed thyroid cancer, although a causal relationship to dulaglutide exposure is uncertain (Sect. 5.3). Nevertheless, dulaglutide, similar to all other long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists, carries an FDA boxed warning around the risk of thyroid C-cell tumors, including MTC (Sect. 6), and the FDA have requested an MTC case registry of ≥15 years duration [52].

Poor adherence to treatment is a widespread problem among patients with T2DM and can represent a barrier to optimal glycemic control [53]. Needle anxiety can also have detrimental consequences for adherence to an injectable treatment [54]. Injection pen devices can help to ease patients’ needle anxiety, as well as other fears associated with traditional vial-and-syringe deliveries [54]. Dulaglutide is available as a prefilled pen that completely hides the needle during all steps of the injection process and has simple instructions (“uncap, place and unlock, inject”) making it relatively easy to use [55]. Moreover, dulaglutide is ready to use, unlike albiglutide, which has to be reconstituted and is only stable for 8 h post reconstitution [56]. In a 4-week study in injection-naive patients, 99.1 % had a successful experience and 99.0 % found it ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to use [57]. Furthermore, once-weekly dosing may be preferred over injectable agents requiring more frequent dosing, with a potential to improve adherence [54].

Although the short-term efficacy of dulaglutide is well established, further longer term studies (>2 years) evaluating the durability of effects on glycemic control will be of interest, as will results from ongoing AWARD trials (NCT01621178, NCT01769378, and NCT02152371) [46].

In conclusion, dulaglutide is a convenient, once-weekly regimen that is administered via a single-dose pen injection system. It is effective and generally well tolerated, as monotherapy or as add-on therapy to other antihyperglycemic drugs, in patients with T2DM. Although more long-term data (>2 years) would be beneficial, dulaglutide is a useful addition to the treatment options available for the management of T2DM.

Data selection sources:

Relevant medical literature (including published and unpublished data) on dulaglutide was identified by searching databases including MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1996) [searches last updated 14 September 2015], bibliographies from published literature, clinical trial registries/databases and websites. Additional information was also requested from the company developing the drug.

Search terms: Dulaglutide, LY 2189265, Trulicity

Study selection: Studies in adult patients with type 2 diabetes who received dulaglutide. When available, large, well designed, comparative trials with appropriate statistical methodology were preferred. Relevant pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic data are also included.

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas: sixth edition 2014 update. 2014. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):140–9.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. AACE/ACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015. doi:10.4158/EP15693.CS.

Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1696–705.

Brown DX, Evans M. Choosing between GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors: a pharmacological perspective. J Nutr Metab. 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/381713.

European Medicines Agency. Trulicity™: summary of product characteristics. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Eli Lilly. Trulicity™ (dulaglutide) injection, for subcutaneous use: US prescribing information. 2014. http://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Eli Lilly Japan Co Ltd. “Torurishiti® subcutaneous injection 0.75 mg Ateosu®” GLP-1 receptor agonist of weekly administration, get the manufacturing and marketing approval in Japan [media release]. 3 July 2015. https://www.lilly.co.jp/.

Glaesner W, Vick AM, Millican R, et al. Engineering and characterization of the long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue LY2189265, an Fc fusion protein. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26(4):287–96.

European Medicines Agency. EPAR: public assessment report for Trulicity. 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Gerich JE. Is reduced first-phase insulin release the earliest detectable abnormality in individuals destined to develop type 2 diabetes? Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl 1):S117–21.

Loghin C, de la Peña A, Cui X. Gastric emptying effects of dulaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [abstract]. In: 23rd Annual Scientific & Clinical Congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2014.

Umpierrez GE, Blevins T, Rosenstock J, et al. The effects of LY2189265, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes: the EGO study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(5):418–25.

Barrington P, Chien JY, Showalter HDH, et al. A 5-week study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of LY2189265, a novel, long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(5):426–33.

Grunberger G, Chang A, Garcia Soria G, et al. Monotherapy with the once-weekly GLP-1 analogue dulaglutide for 12 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes: dose-dependent effects on glycaemic control in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(10):1260–7.

Terauchi Y, Satoi Y, Takeuchi M, et al. Monotherapy with the once weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide for 12 weeks in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: dose-dependent effects on glycaemic control in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Endocr J. 2014;61(10):949–59.

Skrivanek Z, Gaydos BL, Chien JY, et al. Dose-finding results in an adaptive, seamless, randomized trial of once-weekly dulaglutide combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes patients (AWARD-5). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(8):748–56.

Umpierrez G, Povedano ST, Manghi FP. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide monotherapy versus metformin in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-3). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2168–78.

Nauck M, Weinstock RS, Umpierrez GE, et al. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide versus sitagliptin after 52 weeks in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-5). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2149–58.

Dungan K, Povedano ST, Forst T. Once-weekly dulaglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-6): a randomised, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1349–57.

Wysham C, Blevins T, Arakaki R, et al. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide added on to pioglitazone and metformin versus exenatide in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-1). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2159–67.

Giorgino F, Benroubi M, Sun JH. Efficacy and safety of once weekly dulaglutide vs insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin and glimepiride (AWARD-2). Diabetes Care. 2015. doi:10.2337/dc14-1625.

Blonde L, Jendle J, Gross J. Once-weekly dulaglutide versus bedtime insulin glargine, both in combination with prandial insulin lispro, in patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2015;385:2057–66.

Araki E, Inagaki N, Tanizawa Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide in combination with sulphonylurea and/or biguanide compared with once-daily insulin glargine in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, open-label, phase III, non-inferiority study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015. doi:10.1111/dom.12540.

Miyagawa J, Odawara M, Takamura T, et al. Once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide is non-inferior to once-daily liraglutide and superior to placebo in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomized phase III study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015. doi:10.1111/dom.12534.

Weinstock RS, Guerci B, Umpierrez G, et al. Safety and efficacy of once weekly dulaglutide vs sitagliptin after two years in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-5): a randomised, phase 3 study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015. doi:10.1111/dom.12479.

Ferdinand KC, White WB, Calhoun DA, et al. Effects of the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide on ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2014;64(4):731–7.

De La Peña A, Loghin C, Cui X, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once weekly dulaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [abstract no. 981-P]. Diabetes. 2014;63(Suppl 1):A251–2.

Loghin C, de la Pena A, Cui X, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once weekly dulaglutide in special populations [abstract no. 880]. In: 50th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. 2014.

Reaney M, Mitchell BD, Wang P, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with dulaglutide vs. metformin (AWARD-3) [abstract no. 1027-P]. In: 73rd Annual Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. 2013.

Reaney M, Yu M, Adetunji O, et al. Patient-reported outcomes (PRO) from a 104 week, phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled study comparing once weekly dulaglutide to sitagliptin and placebo in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes; the Assessment of Weekly Administration of Dulaglutide in Diabetes (AWARD-5) trial [abstract no. P78]. Diabet Med. 2014;31(Suppl 1):50.

Boye KS, Yu M, Van Brunt K. Patient-reported outcomes with once weekly dulaglutide 1.5 mg versus once daily liraglutide 1.8 mg (AWARD-6) [abstract no. 907]. In: 50th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. 2014.

Van Brunt K, Reaney M, Yu M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with dulaglutide, exenatide, or placebo (AWARD-1) [abstract no. 985]. Diabetologia. 2013;56(Suppl 1):S394–5.

Reaney M, Yu M, Van Brunt K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with once weekly dulaglutide vs. insulin glargine (AWARD-2) [abstract no. 979-P]. Diabetes. 2014;63(Suppl 1):A251.

Reaney M, Yu M, Van Brunt K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with once-weekly dulaglutide vs. insulin glargine, both in combination with premeal insulin lispro, in type 2 diabetes mellitus (AWARD-4) [abstract no. 2393-PO]. Diabetes. 2014;63(Suppl 1):A607.

Adetunji O, Jung HS, Jia N. Assessment by baseline HbA1c of key outcomes for once weekly dulaglutide vs daily insulin glargine, both with prandial insulin lispro, in patients with type 2 diabetes from the Assessment of Weekly Administration of Dulaglutide in Diabetes 4 (AWARD-4) study [abstract no. P152]. Diabet Med. 2015;32(Suppl 1):77.

Cummings M, Gentilella R, Nicolay C. Effect of baseline body mass index (BMI: <30 kg/m2, >30 to <35 kg/m2 and >35 kg/m2) on glycaemic response and weight change in patients with type 2 diabetes with baseline HbA1c >7.5 % after treatment with the once weekly glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) dulaglutide and active comparators in five clinical studies (AWARD 1-5) [abstract no. P144]. Diabet Med. 2015;32(Suppl 1):74.

Vora J, Pechtner V, Jia N. Efficacy and safety of once weekly dulaglutide and once daily insulin glargine at 52 weeks’ treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes in the Assessment of Weekly Administration of Dulaglutide in Diabetes 2 (AWARD-2) study, stratified by duration of diabetes (<5 years, >5 to <10 years, >10 years) [abstract no. P151]. Diabet Med. 2015;32(Suppl 1):77.

Bain SC, Skrivanek Z, Tahbaz A, et al. Efficacy of long-acting once weekly dulaglutide compared with short-acting twice daily (bid) exenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes: a posthoc analysis to determine the influence of baseline HbA1c in the Assessment of Weekly Administration of LY2189265 in Diabetes-1 (AWARD-1) trial [abstract no. P79]. Diabet Med. 2014;31(Suppl 1):50.

Reaney M, Yu M, Lakshmanan M, et al. Treatment satisfaction in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with once-weekly dulaglutide: data from the AWARD-1 and AWARD-3 clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015. doi:10.1111/dom.12527.

Milicevic Z, Anglin G, Harper K. Low incidence of anti-drug antibody in type 2 diabetes patients treated with once-weekly dulaglutide [abstract no. 1135-P]. In: 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. 2015.

Iyer SN, Tanenberg RJ, Mendez CE, et al. Pancreatitis associated with incretin-based therapies. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):e49.

Ferdinand KC, Sager G, Atisso C. Once-weekly dulaglutide dose not increase the risk for CV events in type 2 diabetes: a prespecificed CV meta-analysis of prospectively adjudicated CV events [abstract no. 1125-P]. In: 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. 2015.

Tuttle KR, McKinney TD, Davidson JA. Effects of once-weekly dulaglutide on kidney function in clinical trials [abstract no. 1114-P]. In: 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. 2015.

US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for industry diabetes mellitus—evaluating cardiovascular risk in new antidiabetic therapies to treat type 2 diabetes. 2008. http://www.fda.gov. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

US National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

European Medicines Agency (EMEA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. 2005. http://www.ema.europa.eu/. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry—patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. http://www.fda.gov. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Chiu WY, Shih SR, Tseng CH. A review on the association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/924168.

Byrd RA, Sorden SD, Ryan T, et al. Chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity studies of the long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide in rodents. Endocrinology. 2015. doi:10.1210/en.2014-1722.

Vahle JL, Byrd RA, Blackbourne JL, et al. Effects of dulaglutide on thyroid C-cells and serum calcitonin in male monkeys. Endocrinology. 2015. doi:10.1210/en.2014-1717.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Trulicity to treat type 2 diabetes [media release]. 21 Sept 2014. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm415180.htm.

Asche C, LaFleur J, Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clin Ther. 2011;33(1):74–109.

Ross SA. Breaking down patient and physician barriers to optimize glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2013;126(9 Suppl 1):S38–48.

Eli Lilly. Instructions for use TRULICITY™. 2014. http://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-lowdose-ai-ifu.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

GlaxoSmithKline. Tanzeum (albiglutide): US prescribing information. 2014. http://www.fda.gov/. Accessed 21 Sept 2015.

Matfin G, Van Brunt K, Zimmermann AG, et al. Safe and effective use of the once weekly dulaglutide single-dose pen in injection-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015. doi:10.1177/1932296815583059.

Acknowledgments

During the peer review process, the manufacturer of the dulaglutide was also offered an opportunity to review this article. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Conflict of interest

Celeste Burness and Lesley Scott are salaried employees of Adis/Springer, are responsible for the article content and declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional information

The manuscript was reviewed by: D. S. H. Bell, Southside Endocrinology, University of Alabama Medical School, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; S. R. Bloom, Department of Investigative Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK; G. Dimitriadis, 2nd Department of Internal Medicine, Research Institute and Diabetes Center, “Attikon” University Hospital, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece; J. G. Eriksson, Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, Finland and Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; V. C. Woo, Section of Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burness, C.B., Scott, L.J. Dulaglutide: A Review in Type 2 Diabetes. BioDrugs 29, 407–418 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-015-0143-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-015-0143-4