Abstract

Background

CT-P13 subcutaneous (SC)—the first and only SC version of infliximab—is approved by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This new mode of infliximab administration will allow patients to self-inject at home, significantly reducing the number of outpatient visits and costs of intravenous (IV) administration. This paper describes the economic impact of introducing CT-P13 SC to the market from the UK societal perspective.

Objective

The budget impact analysis was conducted to assess the financial impact of the adoption of CT-P13 SC over a 5-year period.

Methods

A prevalence-based budget impact model was developed incorporating epidemiological data, administration cost data, and market share data. The analysis compared a “world with” CT-P13 SC scenario to a “world without” CT-P13 SC. A sensitivity analysis included dose escalation up to 4.1 mg/kg to reflect the real-world care delivery setting.

Results

Compared to the “world without” scenario, the introduction of CT-P13 SC resulted in cost savings of ₤69.3 million in the UK over a 5-year period. In the scenario analysis, the saving increased to ₤173.5 million over 5 years.

Conclusion

Use of CT-P13 SC may lead to substantial cost savings for the UK society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introducing subcutaneously administered infliximab to the UK market may result in significant economic benefits over a 5-year period. |

Using various estimates of administration costs, the budget impact on the world with subcutaneously administered infliximab was still lower than in the world without it. |

1 Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressive autoimmune disease caused by chronic inflammation in the body that affects a wide range of body systems [1, 2]. RA causes pain, stiffness, and swelling in the joints, primarily affecting the hands, feet, and wrists [3]. RA is associated with a considerable humanistic burden because disease onset typically occurs when people are of working age (30–60 years), with the prevalence rates increasing substantially after the age of 30 years [4, 5]. If inadequately managed, RA can lead to permanent disability due to pain, joint deformities (typically in the fingers and toes), and loss of joint function [6, 7]. Disability rates are seven-fold higher among patients with RA than in the general population [8]. RA and its associated disability significantly reduces health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [9]: patients with RA have a reduced ability to perform daily tasks and participate in social life and leisure activities [10,11,12].

The prevalence of RA in Europe has been steadily rising over recent decades, increasing from 2.65 million people in 1990 to 3.62 million in 2017 [13]. The prevalence of RA is the highest in developed countries [14] and consistently higher within the UK than in other European countries, with prevalence rates of 0.73% in England and 0.74% in Northern Ireland [13]. The UK population aged ≥ 65 years increased from 9.1 million in 1991 to 11.8 million in 2016 (15.8% and 18.0% of the entire UK population, respectively), and is projected to reach 20.4 million in 2066 (26% of the total UK population) [15]. The increasing life expectancy of the UK population [16] will likely be accompanied by a rising incidence of age-related chronic diseases, such as RA, which is expected to put severe stress on the UK healthcare system [17]; thus, there is a need for cost-effective therapies to curtail expenses.

The economic and physical burden associated with RA highlights the need for effective treatments and disease management strategies to delay or prevent disease progression, improving clinical outcomes and HRQoL in people with RA. In recent decades, the management of RA has been revolutionised by the availability of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) that not only provide relief from symptoms, but also slow down disease progression, and, in some patients, induce a state of remission [18]. There are three classes of DMARDs currently available: conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), biological DMARDs (bDMARDs), and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) [18]. First-line treatment of RA is usually supplemented with csDMARDs, such as methotrexate [18]. Patients in whom csDMARD therapy is unsuccessful are typically prescribed a bDMARD or tsDMARD, either as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs [18].

Infliximab—the only intravenous (IV) anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy approved for RA in Europe—was first granted marketing authorisation in 2000 [19]. A range of studies, including randomised clinical trials, meta-analyses, and real-world studies, have demonstrated that infliximab quickly improves disease symptoms, reduces joint erosion, improves physical functioning, and maintains long-term efficacy [19,20,21,22,23]. Through its clinical development programme and in real-world use, infliximab has also been shown to be well tolerated [20,21,22]. Biosimilars of infliximab that are comparable to the reference product in terms of efficacy and safety are now available [24]. The first biosimilar of infliximab, CT-P13 IV (Remsima®), was approved in Europe in 2013 based on safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic data from an extensive and comprehensive programme.

The following five anti-TNFα therapies are approved for the treatment of RA in Europe: infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab [25, 26]. Prior to the approval of CT-P13 subcutaneous (SC) in March 2020, only infliximab was administered intravenously. Both the originator and biosimilar of infliximab must be administered intravenously by a healthcare professional (HCP) every 8 weeks, with each infusion lasting up to 2 h [27, 28]. IV administration of infliximab poses a burden to HCPs, because it requires regular outpatient visits and consumes resources, such as equipment, outpatient bed space, laboratory supplies, facility and overhead expenses, and time spent by HCPs preparing or administering infusions [29]. In the UK, the cost of infliximab administration is £382.00 per infusion [30, 31]. Considering that maintenance therapy with infliximab necessitates an average of 6.5 infusions per year, the annual costs associated with treatment administration alone can exceed £2483 per patient.

In addition to the considerable strain on the healthcare system, IV administration of infliximab is burdensome for patients, as it is inconvenient, time-consuming, and associated with productivity losses. Patients are required to travel to their healthcare provider on a regular basis to receive the treatment, which can take 2 h to infuse [28]. A study in Denmark reported that patients with RA spent, on average, over an hour on transportation each time they travelled to their healthcare provider [32]. Another study in France found that patients with RA lived between 13.5 and 67.7 km from their treatment provider and expended €666 per year to get to their appointments [33]. In addition to out-of-pocket travel costs, IV administration results in productivity loss due to time taken from work. A study of patients with RA in Ireland estimated that per-patient costs associated with time from work and travel to IV infliximab treatment were in excess of €1600 per year [34].

Patients prefer SC administration of infliximab over the IV infusion [35]. Indeed, prescribing trends in Europe indicate that SC forms of anti-TNFα therapy are more commonly prescribed than IV forms, because they allow patients to have a better quality of life [35]. A study of 267 patients with RA found that almost 60% preferred SC treatment to IV infusions, with over 90% indicating convenience as the reason for their preference [36]. In a similar study, the most frequent reason for patients with RA choosing SC treatment was to minimise the time taken for transportation and treatment [37]. The availability of a SC form of infliximab would address the current limitations associated with IV administration and offer patients the safety and efficacy of an established treatment in a more convenient form.

The SC formulations of biologics deliver cost savings and convenience to HCPs as well as patients. The European Medicines Agency authorised the use of CT-P13 SC (the first SC form of infliximab) for RA in November 2019, and for Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis in July 2020. However, the cost of adopting the new mode of infliximab administration has not been evaluated. Thus, this study aimed to perform a budget impact analysis from the societal perspective for the introduction of CT-P13 SC to the UK market where only the IV product is currently available. We compared two models: a “world with” CT-P13 SC and a “world without” CT-P13 SC. In addition, we performed a scenario analysis with different assumptions to reflect various parameters that influence market costs. The model allows the UK society to assess the cost savings of using SC formulation of infliximab over the IV formulation.

2 Methods

2.1 Model Structure

This model estimates the financial impact of treating patients with RA using currently available infliximab therapies from the societal perspective.

A prevalence-based budget impact model was developed to estimate the net cost impact of implementing CT-P13 SC in the UK market. Epidemiology data from the literature, market research data on drug use, and costs of RA were collected and used in the model. The following describes the two modelled scenarios:

-

World with: CT-P13 SC is funded for the treatment of RA.

-

World without: CT-P13 SC is not funded and all patients with RA are treated with IV infliximab.

Patient shares were then applied to the treatment comparators in a world without CT-P13 SC and a world in which CT-P13 SC had been introduced into the treatment landscape. The overall cost of each scenario was estimated by multiplying the number of patients by the cost of each comparator, weighted by its relative frequency of use. The difference in overall costs is referred to as the net budget impact of introducing the SC formulation to the market. The two scenarios were compared to estimate the net budget impact. All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016. All future costs were discounted at the rate of 3.5% to reflect the present value of future costs.

Two scenarios were considered applying different dosing regimens of IV infliximab treatment and the administration costs suggested by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Analysis consisted of:

-

1.

Base case analysis: Includes administration cost of £382 and predicted productivity costs for the duration of the 5-year time horizon [30].

-

2.

Scenario analysis: Assumes that 53.26% of the population receive dose escalation from 3 to 5–7 mg/kg, since this is the most frequent dose applied to patients in clinical practice. Based on the systematic review by Ariza-Ariza et al. [38], we assumed that 53.26% of patients receive dose escalation. We assumed that 61% received 4.5 mg/kg, 21% received 6 mg/kg, 12% received 7.5 mg/kg, and 6% received 9 mg/kg, yielding a weighted average of 4.1 mg/kg dose for the scenario analysis. This scenario also includes administration costs suggested by NICE (£154) and the productivity costs for the duration of the 5-year time horizon.

One-way sensitivity analyses were carried out to show the impact of varying individual parameters. Supplementary Table S1 displays the approach taken for each type of model input. If standard deviation could not be calculated, it was assumed to equal 10% of the base case value.

2.2 Model Assumptions

2.2.1 Treatment and Dosing Information

Treatment with CT-P13 SC is initiated with two IV infusions of infliximab (3 mg/kg): one on the day of treatment initiation (week 0) and another two weeks later (week 2) [28]. Following the IV induction, HCPs can switch patients to receive CT-P13 SC (120 mg) every 2 weeks [28]. Dosage details for CT-P13 SC were obtained from the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) [28].

For adult patients, CT-P13 SC is administered at a fixed dose of 120 mg, while the IV dose is adjusted to body weight. The recommended dosage of IV infliximab for patients with RA is 3 mg/kg; the dosing schedule begins with 3 mg/kg IV infusion followed by an additional 3 mg/kg infusion dose at 2 and 6 weeks after the first infusion, and every 8 weeks thereafter [28].

It was assumed that 31.8% of patients require an IV induction every year, meaning that 31.8% of patients treated with CT-P13 SC undergo IV loading phase (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, among CT-P13 SC-naïve patients, infliximab-naïve patients were 31.8% and 68.2% of patients are switched from IV infliximab to the SC formulation annually. The assumption was made to reflect the 9% discontinuation rate of infliximab in RA and 21% rate for all anti-TNF inhibitors [39, 40]. In years 1–5, 30–60% of infliximab users receive CT-P13 SC and among them, we assume that about 9–19% of patients will be CT-P13 SC-naïve. By applying 31.8% of infliximab-naïve patients each year, we were able to obtain the proportion of naïve patients and discontinuation rate close to the figures from the literature.

If a patient has an inadequate response or loses response to 3 mg/kg infliximab, the dose may be increased stepwise by approximately 1.5 mg/kg [39]. For these patients, the recommended maximum dose is 7.5 mg/kg every 8 weeks or 3 mg/kg as often as every 4 weeks [28, 39]. A systematic review of dose escalation of anti-TNFα agents in patients with RA found that dose escalation with infliximab is prevalent in clinical practice: the authors assessed 16 studies and concluded that of all patients treated with infliximab, 53.26% needed dose escalation ranging from 5 to 7 mg/kg (100 and 114 mg in two studies, additional 1.36 mg/kg, and 5–7 mg/kg in two studies) [38]. Because many patients receive infliximab doses higher than 3 mg/kg, dose escalation was incorporated into the scenario analysis.

In line with recent evidence, this model assumed that there were no differences in efficacy and safety between IV infliximab and CT-P13 SC [40]. A similar assumption was made for patient adherence. While there is no evidence for difference in adherence depending on the route of administration [41], factors such as age and baseline disease activity are associated with non-adherence to anti-TNFα therapy [42] and a comparably high adherence to SC-TNFα [43].

2.2.2 Patient Volume Share

To estimate the market volume share for the world without CT-P13 SC, we conducted market research using sales data of prescribed drugs from IQVIA’s MIDAS database. In the model, CT-P13 SC was assumed to take over the market share from infliximab products. The percentage in the “world without” scenario was based on the sales data for the second quarter of 2019. The “world with” scenario assumed that CT-P13 SC takes 30% from all shares of infliximab in year 1, increasing by 15% yearly up to 60% in year 3, and remaining at 60% until year 5 (Supplementary Table S2).

2.2.3 Productivity

A considerable advantage of having a SC formulation is that patients could self-inject at home. IV infusion takes 2 h on average to infuse, and requires patients to travel to a healthcare provider on a regular basis [27]. This can be burdensome for patients as it is inconvenient, time-consuming, and adds to their already considerable productivity losses. Previous studies on patient preference concluded that a benefit of SC administration is that patients and caregivers do not have to attend hospital appointments, which allows them to spend more time at work. Hence, the base case and scenario analyses incorporated gained productivity of 3.5 h per IV induction (2-h infusion time and 1.5 h of counselling and monitoring) and 2 h per maintenance treatment [27, 44]. For induction, 2-h infusion time follows the NICE guideline and SmPC of the reference infliximab, and 1.5 h was an average of 1-2 h of counselling and monitoring time, derived from the SmPC [27, 44]. As to maintenance treatment, we assumed that patients who receive maintenance therapy are stabilised patients. The accelerated infusions are implemented for the patients under maintenance therapy to take a more conservative approach and to reflect real-life practice, accounting for 1 h of infusion time and 1 h for observation and counselling based on the evidence on safety and effectiveness for rapid infusion [45, 46].

2.3 Data Sources

2.3.1 Population Data

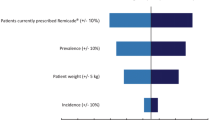

The UK population data were extracted from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) databases and the prevalence rate was obtained from the Global Health Data databases [13, 47]. The number of patients eligible for treatment was calculated using UK population data (66.4 million) [47], prevalence of RA (0.74%) [13], and the proportion of patients eligible to receive the infliximab regimen (8.29%). The latter percentage was obtained by multiplying the proportion of patients eligible for bDMARDs from a literature review (41.04%) by the market share of infliximab obtained from the IQVIA sales data (20.28%) (Supplementary Table S3). Thus, it was estimated that the total number of UK patients receiving infliximab for RA is 40,906 (Fig. 1).

2.3.2 Cost Data

The model includes direct treatment costs, such as those associated with drug acquisition and drug administration, and indirect costs, such as productivity costs.

2.3.2.1 Drug Costings

Drug acquisition costs were calculated using pack prices from the British National Formulary (BNF) in the year 2020. The prices were standardised into price per mg and price per unit (Supplementary Table S4). The treatment dose and administration schedule (including any necessary IV inductions for SC treatments) were used to calculate the total cost of treatment up to a 5-year time horizon. The drug cost of CT-P13 SC 120 mg solution for injection was assumed to be the same as that of CT-P13 100 mg vial (£377.44). This was based on the list price published in NICE BNF and does not represent the true transaction price, which is confidential and varied by procurement channels.

The total cost of SC treatments was calculated by multiplying the price per unit by the total units in an annual dose, taking into account 5 years of IV induction costs for CT-P13 SC.

The calculation of acquisition costs for IV infliximab formulations is more complex due to the requirement for weight-based dosing. IV drugs are supplied in vials and administered to patients at a set number of mg per kg, meaning that the number of vials required to treat a patient will depend on their body weight; hence, patient body weight was incorporated into the model. In the analyses, the mean number of vials per infusion was calculated according to the mean weight: three vials for the base case and four vials for the dose-escalated scenario. The total cost of IV drugs was calculated by multiplying the price per mg by the mean number of mg in a single vial and the mean number of vials used per patient per annual dose. Vial sharing was not considered in the analysis.

2.3.2.2 Administration Costs

The administration costs accounted for both the cost of actual treatment administration (including staff, equipment, and concomitant medication costs) and proximal costs (costs associated with general practitioner [GP] and clinic visits, training for self-administration, follow-up visits, and laboratory tests). These costs were between £0.52 and £20.33 per SC administration and between £199 and £426 per IV administration [48]. In the base case analysis, the model incorporated administration costs as a single cost per SC or IV administration (£3.32 and £382.00, respectively) [30, 44]. The costs of SC administration have been increased in the model, as stated in the ONS database, to reflect inflation [49]. The model expects SC formulation to offset administration costs because of the option to self-inject at home.

The IV administration cost parameter used in the base case model was fixed at £382.00, as suggested by Tetteh et al. [30, 38]. The administration cost included proximal costs (such as GP and clinic visits, training, pre-therapy counselling, pharmacy costs, pre-treatment medication, post-treatment and laboratory tests), and physical administration costs, staff costs, equipment and consumables, and concomitant medications [30, 38]. The model took gamma distribution to the deterministic estimates and ran Monte Carlo simulations to adjust for uncertainty in the incidence, severity of illness, and treatment outcomes [30, 38].

NICE also provided estimates of administration costs [44]. NICE final appraisal of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab, and abatacept for RA not previously treated with DMARDs, or after the failure of conventional DMARDs only, indicates a cost of £154 and time of 1 h (taken from the NICE technology appraisal guidance on tocilizumab) [44]. The assessment group decided that the cost of tocilizumab infusion was comparable to that of infliximab infusion in TA375 [44]. In the tocilizumab assessment report, the administration cost was between £154 and £308, and considered to be an important parameter with the potential to change the cost-effectiveness result [44]. The assessment group stated that the average administration cost of SC products was £3.05 [44]. In the scenario analysis, we incorporated variation in the administration cost that scenarios consist of a set of value of administration cost from NICE as reference source: £154 (inflated to £167.68 from 2015 to 2019) and £3.05 (inflated to £3.32 from 2015 to 2019) [44].

2.3.2.3 Productivity Cost

Increased productivity costs resulting from the lack of need for infusion centre or clinic visits were calculated based on the hourly wage of full-time workers from the UK ONS database (£17.50) [50, 51]. National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society Survey found that approximately 45.15% of patients with RA are unemployed and, thus, we set the population employment rate at 54.86% [52].

Productivity costs are calculated by summing the time spent away from work on travel to receive treatment and subsequently receiving treatment, multiplied by the hourly wage. This is then adjusted to account only for patients who are in employment using the unemployment rate. It is assumed that patients receiving SC treatment require no time away from work for travel or treatment administration.

3 Results

3.1 Base Case

The base case analysis calculated the budget impact of CT-P13 SC in a time horizon of 1–5 years and compared CT-P13 SC with IV infliximab only, with no other treatments included in the model.

The potential financial benefits of adopting a SC formulation in the market are demonstrated in Fig. 2. For treating the eligible patients, the total net budget in the world with CT-P13 SC was lower than that in the world without CT-P13 SC. In both the “world with” and “world without” scenarios, the overall costs of infliximab declined for the fifth successive year because the model reflects a 3.5% annual discount rate for costs and increasing patient shares being allocated to more costly treatment options (Supplementary Table S5). We also observed cost differences between the “world with” and “world without” scenarios. This total budget decrease was not due to lower drug acquisition costs, but largely due to administrative cost savings. The slightly higher drug acquisition cost of the SC formulation was offset by its lower administration and productivity costs compared to those of the IV formulation. A detailed cost breakdown is presented in Supplementary Table S5 and S6.

The net budget impact is shown in Table 1. A total of £69,303,310 was saved. The amount varied from £8,923,881 to £16,479,486 per year from year 1 to year 5. The lowest budget impact was recorded in year 1 due to the lowest market share. Year 3 was the highest cost-saving year, likely due to the highest market penetration rate. Figure 3 illustrates the budget impact of implementing CT-P13 SC in the market: as in Table 1, the magnitude of cost-saving increased after year 1 and peaked in year 3.

3.2 Scenario Analysis

The scenario analysis was performed on the assumption that approximately half of the patients receiving infliximab require dose escalation.

The budget impact of the dose escalation scenario analysis is summarised in Fig. 3. The budget savings were greater in the dose escalation scenario than in the base case scenario because of the higher infliximab dose. The results of the dose escalation scenario analysis followed the same trends as those of the base case analysis (Fig. 4); however, the total saving was higher than the base case results, ranging from £22,210,213 to £41,225,439, and £173,493,016 in total (Table 1).

3.3 One-Way Sensitivity Analysis

The results of the one-way sensitivity analysis are presented in Figs. 5 and 6. The variables are shown in a decreasing order. In the base case, the variable with the biggest impact over 5-year budget savings was the cost of IV administration, followed by the prevalence of RA and the number of patients eligible for biologic treatment (Fig. 5). The scenario analysis was the most strongly influenced by factors related to the patient population, such as RA prevalence and eligibility for biologic treatment (Fig. 6). One-way sensitivity analysis for the scenario analysis concluded that a conservative estimate of cost savings from administration may result in a minimum saving of £150 million in 5 years. These results attest that there are budget savings to be had from switching from IV to CT-P13 SC from a societal perspective.

4 Discussion

This model estimates the financial impact of introducing SC infliximab for patients with RA from the UK societal perspective. Before CT-P13 SC was available, infliximab was administered intravenously only, which consumed additional healthcare resources, including facility costs, equipment, and HCP time, as well as causing patient inconvenience, productivity losses, and other indirect expenses. Introducing SC infliximab to the UK market is expected to lead to savings through reduced productivity losses and lower administration costs.

Our model has some limitations. In the current delivery setting in the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) assumes the cost of administration through reimbursing providers in accordance with a set tariff. As it is difficult to estimate the true administration cost, and because the administration cost was the most influential factor in the sensitivity analysis of the base case, two sets of administration costs were explored to estimate the various degrees of impact of introducing CT-P13 SC to the market. The base case used £382 per IV administration, as suggested by Tetteh et al. [30], while scenario analysis used £167.68, which is an estimate derived from NICE technology appraisal guidance. Additionally, the model did not take treatment discontinuation into account, which can potentially overestimate the costs when switching to another therapy. Nonetheless, the model concluded that with the suggested price of CT-P13 SC, savings generated from avoiding IV administration and productivity loss will compensate for the higher drug acquisition costs and yield significant cost saving to society.

In a recent survey conducted among rheumatologists in the UK, interviewees reported that the average compensation tariff for infliximab administration was £414, which is close to the value used in the base case analysis. Further, the published tariff value for “Complex Chemotherapy, including Prolonged Infusion Treatment, at First Attendance” priced IV administration at £426 and SC administration at £3.32–£6.04 [48]. The survey reported a large regional variation and other tariff codes that are inconsistent with the reported average of £414, with the least expensive tariff being £100 for “outpatient procedure” [48]. Tariff costs do not consider other costs, such as the cost of consumables, vial sharing, and compounding [48]. The highest value coded for infliximab was £1000 per infusion [48]. According to the survey, the estimated average in-tariff plus non-tariff costs per administration were £441 for IV infliximab [48]. The cost of IV administration suggested by NICE was significantly lower (£167.68) and had a large variation. Further updates on the administration costs of IV infliximab are warranted.

This study assumes that there are no differences in health benefits, efficacy, or safety between IV infliximab and CT-P13 SC. The benefits of IV infliximab administration for the management of RA are well recognised. For example, the recommended dosage of 3 mg/kg could be increased up to 7.5 mg/kg to improve the response to the drug in certain patient populations. Serum trough levels of infliximab correlate with the clinical response to infliximab treatment [53, 54]: The RISING study concluded that higher infliximab trough serum concentration was associated with clinical response or greater inhibition of progression of joint damage [53]. Consistent with these findings, Wolbink et al. reported that non-responders had significantly lower trough serum infliximab levels than responders, and that low serum levels were correlated with poor clinical improvement based on DAS28-CRP [54]. Dose escalation has not been investigated for CT-P13 SC; however, the pivotal study (NCT: 03147248) demonstrated that SC administration had higher efficacy than IV administration owing to more consistent serum concentration as a result of more frequent dosing [53]. Further, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that CT-P13 SC is more efficacious than IV infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept [55]. Thus, cost-utility or cost-effectiveness analyses with additional clinical data or real-world evidence may be required, e.g., improved efficacy of CT-P13 SC over IV infliximab, dose escalation population for CT-P13 SC. If CT-P13 SC offers an improvement over the existing anti-TNFα therapies, further findings in pharmacoeconomic studies will result in more favourable outcome on CT-P13 SC.

Although this study explored various administration costs, it did not model the true transaction cost of acquiring biologics. The model incorporated the official price of infliximab listed in the BNF, not accounting for any discounts. The price of CT-P13 SC is subject to a discount in the UK as of the second half of 2020; however, the magnitude of the discount is undisclosed. The in-market price of infliximab vials, which is discounted compared to the list price and pre-approved between pharmaceutical companies and the NHS, is confidential and was not considered in this analysis. Depending on the magnitude of the discount offered for the IV products, potential savings may differ from those calculated by this model.

This study assumed that the uptake of CT-P13 SC was 30% of the total infliximab market in year 1, 45% in year 2, and 60% in years 3–5. This is based on a survey carried out in rheumatologists, which concluded that, on average, 50% of patients with RA receiving IV infliximab would benefit from switching to SC administration in the first year after introduction. The current model assumed gradual uptake of the new formulation, taking into consideration the sales uptake of IV infliximab in the first few years. Utilisation over the 5 years is assumed to be the same between the model and the rheumatologist survey. Moreover, the model excluded additional infliximab-naïve patients who might have chosen to receive CT-P13 SC instead of other anti-TNFα SC formulations, which may lessen the effect of adopting CT-P13 SC in the market.

5 Conclusion

Our budget impact model suggests that avoiding the need to administer IV infliximab in the hospital will greatly reduce the cost to the society. The current model strived to capture various figures of IV administration cost in the UK. Although it was difficult to estimate the true infliximab administration costs, we have used diverse parameters to reflect the current market realities. Our data indicate that introducing subcutaneously administered infliximab may result in significant economic benefits for the UK society. This analysis can be expanded to other countries. We anticipate that countries with higher administration and/or productivity costs associated with IV infliximab would gain more significant cost benefits from introducing CT-P13 SC to the market.

References

The Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis across Europe: a Socioeconomic Survey (BRASS): British Society of Rheumatology.

A D-G. Rheumatoid arthritis. 2019. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Rheumatoid-Arthritis. Cited 24 August 2020.

(NRAS) NRAS. What is RA? https://www.nras.org.uk/what-is-ra-article#:~:text=About%201%25%20of%20the%20population,a%20bit%20older%20for%20men. Cited 27 July 2020.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD results tool. Global burden of disease data resources. 2017. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Freeman J. RA facts: what are the latest statistics on rheumatoid arthritis? 2018. https://www.rheumatoidarthritis.org/ra/facts-and-statistics/. Cited 25 Aug 2020.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A, Burmester GR, Emery P, Firestein GS, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2018;4(1):18001.

Scott DL, Pugner K, Kaarela K, Doyle DV, Woolf A, Holmes J, et al. The links between joint damage and disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2000;39(2):122–32.

Sokka T, Krishnan E, Häkkinen A, Hannonen P. Functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients compared with a community population in Finland. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):59–63.

Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L, Hotopf M, Kingsley GH, Norton S, et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):123–30.

Tuominen R, Tuominen S, Suominen C, Möttönen T, Azbel M, Hemmilä J. Perceived functional disabilities among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(5):643–9.

Leino M, Tuominen S, Pirilä L, Tuominen R. Effects of rheumatoid arthritis on household chores and leisure-time activities. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(11):1881–8.

Wikström I, Book C, Jacobsson LT. Difficulties in performing leisure activities among persons with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective, controlled study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45(9):1162–6.

GBD Results Tool. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Chronic rheumatic conditions. https://www.who.int/chp/topics/rheumatic/en/. Cited 25 Aug 2020.

Living longer: how our population is changing and why it matters. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13. Cited 25 Aug 2020.

Morgan E. National life tables, UK: 2016 to 2018. 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/nationallifetablesunitedkingdom/2016to2018. Cited 25 Aug 2020.

Belloni BFA. Ageing and health expenditure. 2019. https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2019/01/29/ageing-and-health-expenditure/. Cited 25 Aug 2020.

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–77.

Papadopoulos CG, Gartzonikas IK, Pappa TK, Markatseli TE, Migkos MP, Voulgari PV, et al. Eight-year survival study of first-line tumour necrosis factor α inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: real-world data from a university centre registry. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2019;3(1):rkz007.

Westhovens R, Yocum D, Han J, Berman A, Strusberg I, Geusens P, et al. The safety of infliximab, combined with background treatments, among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and various comorbidities: a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1075–86.

Perdriger A. Infliximab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Biologics. 2009;3:183–91.

Agency EM. Remicade. Infliximab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. 2019. Cited 25 Aug 2020.

Holroyd CR, Parker L, Bennett S, Zarroug J, Underhill C, Davidson B, et al. Switching to biosimilar infliximab: real world data in patients with severe inflammatory arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(1):171–2.

Moots RJ, Curiale C, Petersel D, Rolland C, Jones H, Mysler E. Efficacy and safety outcomes for originator TNF inhibitors and biosimilars in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis trials: a systematic literature review. BioDrugs. 2018;32(3):193–9.

Upchurch KS, Kay J. Evolution of treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2012;51(suppl_6):vi28–36.

Schwartzman S, Morgan GJ, Jr. Does route of administration affect the outcome of TNF antagonist therapy? Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S19–23.

Janssen Biologics B.V. Remicade 100 mg powder for concentrate for solution for infusion. [Summary of Product Characteristics]. European medicines agency website. 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/remicade. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

Celltrion Healthcare Hungary Kft. Remsima 100 mg powder for concentrate for solution for infusion [Summary of Product Characteristics]. European medicines agency website. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/remsima#product-information-section. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Schmier J, Ogden K, Nickman N, Halpern MT, Cifaldi M, Ganguli A, et al. Costs of providing infusion therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in a hospital-based infusion center setting. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8):1600–17.

Tetteh EK, Morris S. Evaluating the administration costs of biologic drugs: development of a cost algorithm. Health Econ Rev. 2014;4(1):26.

Soini EJ, Leussu M, Hallinen T. Administration costs of intravenous biologic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Springerplus. 2013;2:531.

Sørensen J, Linde L, Hetland ML. Contact frequency, travel time, and travel costs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheumatol. 2014;2014:285951.

Fautrel B, Woronoff-Lemsi MC, Ethgen M, Fein E, Monnet P, Sibilia J, et al. Impact of medical practices on the costs of management of rheumatoid arthritis by anti-TNFalpha biological therapy in France. Jt Bone Spine. 2005;72(6):550–6.

Walsh CA, Minnock P, Slattery C, Kennedy N, Pang F, Veale DJ, et al. Quality of life and economic impact of switching from established infliximab therapy to adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(7):1148–52.

Stoner KL, Harder H, Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA. Intravenous versus subcutaneous drug administration which do patients prefer? A systematic review. Patient Patient Cent Outcomes Res. 2015;8(2):145–53.

Navarro-Millán I, Herrinton LJ, Chen L, Harrold L, Liu L, Curtis JR. Comparative effectiveness of etanercept and adalimumab in patient reported outcomes and injection-related tolerability. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0149781.

Huynh TK, Ostergaard A, Egsmose C, Madsen OR. Preferences of patients and health professionals for route and frequency of administration of biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adher. 2014;8:93–9.

Ariza-Ariza R, Navarro-Sarabia F, Hernández-Cruz B, Rodríguez-Arboleya L, Navarro-Compán V, Toyos J. Dose escalation of the anti-TNF-α agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A systematic review. Rheumatology. 2006;46(3):529–32.

Rahman MU, Strusberg I, Geusens P, Berman A, Yocum D, Baker D, et al. Double-blinded infliximab dose escalation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1233–8.

Westhovens R, Wiland P, Zawadzki M, Ivanova D, Kasay AB, El-Khouri EC, et al. Efficacy, pharmacokinetics and safety of subcutaneous versus intravenous CT-P13 in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized phase I/III trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;60(5):2277–2287

Khan S, Rupniewska E, Neighbors M, Singer D, Chiarappa J, Obando C. Real-world evidence on adherence, persistence, switching and dose escalation with biologics in adult inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: a systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(4):495–507.

Salaffi F, Di Carlo M, Farah S, Carotti M. Adherence to subcutaneous anti-TNFα agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is largely influenced by pain and skin sensations at the injection site. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23(4):480–7.

Bhoi P, Bessette L, Bell MJ, Tkaczyk C, Nantel F, Maslova K. Adherence and dosing interval of subcutaneous antitumour necrosis factor biologics among patients with inflammatory arthritis: analysis from a Canadian administrative database. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e015872.

Stevenson M, Archer R, Tosh J, Simpson E, Everson-Hock E, Stevens J, et al. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and after the failure of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs only: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(35):1–610.

Clare DF, Alexander FC, Mike S, Dan G, Allan F, Lisa W, et al. Accelerated infliximab infusions are safe and well tolerated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21(1):71–5.

McConnell J, Parvulescu-Codrea S, Behm B, Hill B, Dunkle E, Finke K, et al. Accelerated infliximab infusions for inflammatory bowel disease improve effectiveness. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2012;3(5):74–82.

(ONS) OfNS. United Kingdom population mid-year estimate. 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates. Accessed 10 Oct 2020.

Heald A, Bramham-Jones S, Davies M. Comparing cost of intravenous infusion and subcutaneous biologics in COVID-19 pandemic care pathways for rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases—a brief UK stakeholder survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;e14341.

Consumer price inflation tables. In: Statistics OfN, editor. Office for National Statistics; 2020.

(ONS) OfNS. Average actual weekly hours of work for full-time workers (seasonally adjusted). 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/timeseries/ybuy/lms. Cited 4 Nov 2020.

(ONS) OfNS. AWE: whole economy level (£): seasonally adjusted total pay excluding arrears. 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/timeseries/kab9/emp. Cited 4 Nov 2020.

N NRAS. ‘I Want to Work’ Survey. 2014.

Takeuchi T, Miyasaka N, Tatsuki Y, Yano T, Yoshinari T, Abe T, et al. Baseline tumour necrosis factor alpha levels predict the necessity for dose escalation of infliximab therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(7):1208–15.

Wolbink GJ, Voskuyl AE, Lems WF, de Groot E, Nurmohamed MT, Tak PP, et al. Relationship between serum trough infliximab levels, pretreatment C reactive protein levels, and clinical response to infliximab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):704–7.

Caporalia R, Allanore Y, Altenc R, Combed B, Dureze P, Iannonef F, Nurmohamedg MT, Leei SJ, Kwonj TS, Choij JS, Parki G, Yook DH. Efficacy and safety of infliximab subcutaneous versus adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab intravenous in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review and treatment comparison. 2020;17(1):85–99.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was supported by Celltrion Healthcare.

Conflict of interest

HGB, MYJ, HKY, JP, and TSK report that they have a financial interest in Celltrion Healthcare, a company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. All authors are employed by Celltrion Healthcare.

Availability of data and material

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Table file.

Code availability

The model is available on request.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualisation: TSK, MYJ; original draft: HGB, MYJ; editing: HGB, MYJ; data analysis: MYJ, HKY; review: TSK, HKY, JP; supervision: TSK

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Byun, H.G., Jang, M., Yoo, H.K. et al. Budget Impact Analysis of the Introduction of Subcutaneous Infliximab (CT-P13 SC) for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis in the United Kingdom. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 19, 735–745 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-021-00673-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-021-00673-1