Abstract

With more disease- and symptom-specific measures available and research pointing to increased usefulness, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can be routinely used in clinical care. PROMs increase efficiency in healthcare, improve the clinician–patient relationship, and increase patient satisfaction with their care. PROMs can be administered before, during, and after clinic visits using paper-and-pencil, mobile phones, tablets, and computers. Herein, we combine available literature with expert views to discuss overcoming barriers and helping dermatologists incorporate PROMs into routine patient-centered care. We believe dermatology patients will benefit from broader PROM implementation and routine clinical use. However, a few major barriers exist: (1) cost to implement the technology, (2) selecting the right PROMs for each disease, and (3) helping both patients and clinicians understand how PROMs add to and complement their current clinical experience. We provide recommendations to assist dermatologists when considering whether to implement PROMs in their practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patient-reported outcomes provide clinically relevant information, giving insight into how skin conditions affect dermatology patients. |

Patient-reported outcomes can be broadly implemented into routine dermatologic practice. We encourage and provide recommendations to assist dermatologists when considering whether to implement patient-reported outcome measures in their practices. |

1 Introduction

The Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report on patient-centered care shifted medical decision making to optimizing patient outcomes and identifying what matters most to patients [1]. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) help quantify the patient's voice during the clinic visit [2]. PROMs are validated survey instruments that offer insight into multiple aspects of a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQL), such as itch, pain, mental health, physical functioning, sleep interference, and self-esteem.

Dermatologic care aims to improve skin-related morbidity, including HRQL. Patients have reported that dermatologists have “poor comprehension of the psychological implications of skin diseases” and are “insensitive to their patients’ emotional suffering” [3]. The psychological morbidity from skin disease is associated with the patient’s, not the clinician’s, assessment of severity [4].

PROMs are often questionnaires, scales, or single-item measures, either via paper-and-pencil or electronically. PROMs can function as a baseline from which clinicians can monitor improvement with treatment, side effects, or flares. This opinion piece seeks to discuss how to overcome barriers to dermatologists incorporating PROMs into routine patient-centered care and describe some of the many validated general and dermatology-specific PROMs from an ever-growing pool, enumerating their distinctive features, licensing information, and where each can be found. We hope this knowledge empowers dermatologists to identify and implement PROMs in their clinical practice to complement clinical care.

2 Methods

We provide a sample of the most used PROMs relevant to dermatology identified through the MEDLINE database and consulting dermatologists who actively use PROMs in clinic. A current list of available PROMs and how to access them can be found on the Dermatology PRO Consortium website: https://www.dermproconsortium.org/pro-list. We welcome additions to this list.

3 Benefits of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in Clinical Care

PROMs have improved clinical decision making and informed patient–clinician interactions in several clinical areas, including oncology [5], orthopedic surgery [6, 7], acute care [8], heart failure [9], and opioid addiction [10]. In cancer patients, PROM use improved survival by about 6 months by identifying and addressing symptoms earlier to prevent further harm [5]. PROMs provide a patient-centered perspective on treatment effectiveness and the importance of clear skin in dermatology [11, 12]. For example, isotretinoin clinically meaningfully improves HRQL as measured by Skindex-16 [13]. PROMs can also help determine if prescribed medications are working properly (from the patient’s perspective) or causing significant side effects [14].

PROMs provide patients with a structured method to share more with clinicians than might be said otherwise. In a review of 42 PROM studies, patients did not “feel it was appropriate to discuss emotional, functional or [HRQL] issues with doctors, and doctors did not perceive this was within their remit” [15]. Thus, patients can have potentially treatable issues that go unaddressed because of a lack of communication. Finally, web-based PROMs for symptom surveillance with cancer patients are cost effective and decrease follow-up cost [16, 17].

In dermatology, dozens of PROMs have been developed and validated across several skin diseases and symptoms. Because these capture the patient’s voice as to the effects of their skin disease (and its treatments) on HRQL, PROMs could serve as a vital sign in dermatology that is patient-derived, quantifiable, and can be consistently measured [18, 19]. PROMs help patients communicate their concerns to a clinician rapidly and systematically [15]. However, the evidence base for clinical significance of dermatology PROMs is currently lacking; more studies are needed on the value of PROMs in dermatology practice, but calls for routine use are gaining momentum. The European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Quality of Life Task Force’s 2016 expert-opinion statement tasked dermatologists to adopt PROMs for routine use in clinical practice and treatment decisions [20]. However, selecting an appropriate PROM for clinical use can be challenging.

4 Overview of Psychometric and Practical Properties

A key barrier to the routine clinical use of PROMs for assessing skin disease impact is establishing an accurate and reliable measure that can be meaningfully interpreted [21, 22]. PROMs comprise a series of items, the responses to which can be translated into a score that indicates patient-reported outcomes, such as current symptom severity or HRQL. In addition to being valid, reliable, and responsive, a clinical PROM should be brief, interpretable, accessible, and actionable [22].

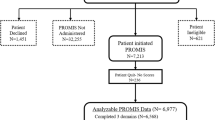

Validity is an assessment’s capacity to measure what it is supposed to measure and not measure what it is not supposed to measure [21]. A valid PROM should be developed using a qualitative framework of interviewing patients and clinicians to determine how best to capture the desired input (symptoms, HRQL, etc.). Validity can also be assessed by testing a new measure against an available ‘gold standard.’ In the US, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a collection of well-validated PROMs developed using National Institutes of Health funding [23], and these have been validated with reviews by expert panels, patient interviews, and clinical validity evidence [24]. More PROMIS domains are being developed, and relevant PROMIS domains can be tailored to the needs of dermatology patients (e.g., PROMIS Itch [24,25,26,27,28]).

Reliability is an assessment’s ability to provide consistent scores over time, meaning that the same patient will answer in the same way if they are clinically unchanged [21]. PROMIS measures have been tested for reliability [29,30,31,32]. Also, both Skindex and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) have high internal consistency [33,34,35,36], which assesses whether a patient responds similarly to similar questions [21]. For example, a patient who strongly agrees that their skin itches should also agree that their skin symptoms bother them. For routine clinical use, a trade-off exists between high reliability and the need for shorter assessments to decrease survey fatigue [24]. Some PROMs are transitioning to computer-adaptive tests (CATs). CATs tailor additional questions drawn from a large item bank based on individual responses to prior items and refine an individual’s score, often with fewer questions [37,38,39].

Responsiveness refers to an assessment’s ability to identify changes over time [21]. For PROMs to adequately assess treatment effectiveness, they should show improvements or worsening of symptoms or HRQL in response to treatment [21]. In a study comparing DLQI, Short Form 36 (SF-36), and EuroQOL 5D (EQ-5D), DLQI was most responsive to changes in psoriasis treatments [36]. Additionally, acne patients receiving isotretinoin are more affected mentally than physically, and changes over time can be observed using Skindex-16 [13].

The minimal important change (MIC) of a PROM supports interpretation of clinical significance. MIC helps distinguish between clinically significant (clinically meaningful) and statistically significant differences [40]. MICs have been reported for only a few dermatology measures, including Skindex [41,42,43] and DLQI [44].

Importantly, many PROMs have not been validated in diverse populations and age groups. Small differences in wording can influence interpretation. Children and individuals with special needs may require additional consideration in that PROMs should be designed and validated for these groups or for a proxy (e.g., a parent).

Finally, it is important that PROMs are practical for clinical use [22]. Specifically, PROM scores should be actionable, prompting clinicians to further testing, treatment adjustments, or referrals. A high depression screening score can prompt a referral to a mental health specialist [45]. Worsening PROM scores can prompt a recommendation to switch from topical to systemic agents for psoriasis or acne. An ideal PROM for clinical use will also be freely available for administering electronically or via paper-and-pencil.

5 Selecting the Best PROM(s) for Your Clinical Practice

Of hundreds of existing PROMs, this opinion piece summarizes key features of some widely used general and dermatology-specific (Table 1), skin disease-specific (Table 2), and symptom-specific PROMs (Table 3). These measures vary greatly in purpose (e.g., HRQL vs symptom assessment), clinical utility, number of questions, time to complete, and accessibility. We recommend only using PROMs that assess aspects relevant and useful to understanding the dermatology patient’s condition and thereby informing medical decision making.

Some clinicians might find a more general assessment tool (Table 1) more clinically useful, as they address a broader variety of concerns, including both physical and mental health, fatigue, social isolation, pain, etc. [46, 47]. These measures provide insight into a person’s overall health, but lack specificity as to which aspects are impacted by their skin condition.

Dermatology-specific measures (Table 1) assess a range of concerns related to or affected by a patient’s skin condition. Two measures commonly used in clinical trials and epidemiologic research are DLQI and Skindex-16. In 10 questions, DLQI measures symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work/school, personal and sexual relationships, and treatment [48]. Children’s DLQI focuses on how skin issues affect schooling and bullying and removes the question about sex [49]. Skindex-16 provides an intuitive score on a 0–100 scale, with 100 representing maximal impact on HRQL, for each of three domains: (1) symptoms, (2) emotional impact, and (3) functional impact [50]. In clinical practice, most dermatologists at University of Utah Health (UUH) reported difficulty interpreting DLQI’s non-intuitive scoring [51].

For those in specialized dermatology clinics (e.g., atopic dermatitis, psoriasis), disease- or symptom-specific PROMs (Tables 2, 3) may provide additional disease-specific insight for chronic skin conditions with specific symptoms or effects. For example, the patient-oriented eczema measure (POEM) measures symptom frequency and severity in adult and pediatric atopic dermatitis patients [52, 53]. An app called My Eczema Tracker can track POEM scores and eczema severity, akin to glucose tracking apps for diabetes patients, to help identify triggers and eczema flares and help clinicians offer personalized treatment recommendations [52].

6 Additional Considerations in Optimizing PROM(s) for Your Practice

Clinicians who desire to use PROMs in dermatology clinics need to balance the information gained without taking too much clinic time or causing survey fatigue. Longer assessments lead to lower response rates [54]. However, PROMs vary on both the content and relevance of the questions [54], and patients are willing to complete longer PROMs when they see their value and relevance [55]. Skindex-Mini, with three questions, was developed specifically to balance the need for dermatology-specific information with minimal patient burden and may be feasible for integration into the American Academy of Dermatology’s (AAD) DataDerm [56, 57].

Clinicians should consider timing of PROM collection, determining when a PROM score will be most useful. For example, all new patients to UUH Dermatology are sent an email asking them to complete PROMs online in the week prior to their initial visit. Patients who have not done so are asked at check-in to complete them on a tablet in the waiting room to avoid encroaching on limited clinic time [45, 58]. This ensures that the clinician can access Skindex-16 scores in the electronic health record (EHR) while the patient is in the room. For patients with inflammatory or chronic skin conditions, PROM intervals should coincide with when the clinician wants to assess treatment response and monitor for adverse events. We are gathering real-world examples of how PROM scores have changed clinical care in dermatology, such as identifying unspoken melanoma concerns and non-obvious difficulties patients have with their skin—these are noted on the Dermatology PRO Consortium website [59].

A final consideration in PROM selection is cost—not all PROMs are free to access. We have included relevant licensing requirements and associated costs in Tables 1, 2 and 3, but these are not exhaustive and can change. A current list is maintained online by the Dermatology PRO Consortium [60]. For a more thorough treatise on how to select and implement PROMs in clinical practice, the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) produced a user’s guide [61]. Additionally, the international COSMIN initiative hosts free tools to help clinicians determine which measures are most appropriate for their goals [62].

7 Administering PROM(s) in Your Clinical Practice

Used regularly, PROMs can track patients’ symptom improvements (or lack thereof) with treatment. Paper-and-pencil has the advantage of tailoring PROMs to individual patients but requires staff or clinicians to manually calculate scores and enter them into the EHR. Electronic PROMs can be captured using a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant app or software, and scores can be calculated automatically. When PROM data are collected in a Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)-compatible manner, the data can link directly to a patient’s EHR. Paper and electronic PROMs are equivalent in responses and scores [63]. Electronic options may be useful in the growing field of teledermatology, where skin diseases can be tracked remotely with PROMs to offer cost-effective and reliable dermatologic care [64,65,66].

8 Potential Barriers to Routine PROM Use in Clinical Practice in Dermatology

Despite their benefits, to our knowledge, few US clinics have broadly implemented PROMs, for various reasons including perceived lack of relevance, lack of time in clinic, lack of reimbursement in the fee-for-service pay model, and lack of a universal EHR, among others [67,68,69]. Conversely, England’s National Health System has collected PROMs nationwide since 2009 [70].

At UUH Dermatology, PROM data has been used since 2017 to help track changes in dermatology patient symptoms and HRQL, enhance clinician–patient communication by providing insight into motivators for the patient visit, evaluate treatment effectiveness, and tailor treatment decisions [58, 71]. Based on change management principles [72], to successfully implement PROMs, one needs to identify early adopters, communicate the vision with the team, empower others, create short-term wins, and consolidate improvements.

By focusing early efforts with a few clinicians, one can work out institutional kinks and capture early successes. For example, we started using DLQI because it is commonly used in trials, but our dermatologists struggled with the non-intuitive scoring system. We switched to Skindex-16 and clinical PROM use increased immediately because clinicians intuitively understood a 0–100 scale. Also, we celebrated early successes in faculty meetings and grand rounds, identifying patient experiences where PROMs changed care or assisted with billing documentation requirements or prior authorization for an expensive medication [73].

Without additional research to support such efforts, changes in PROM scores should not be used as a surrogate for care quality [67, 68]. PROMs can function complementarily to clinician-reported outcome measures [74]. For example, a randomized trial showed that HRQL improvements, as measured with both Skindex-16 and DLQI, were similar for psoriasis patients followed via either teledermatology (online) or in person [75]. With the increased uptake of teledermatology due to COVID-19 [76, 77], PROMs offer value by remotely identifying acute flares in chronic skin issues, like autoimmune bullous diseases [78], which can trigger an urgent follow-up appointment.

Despite its challenges, developing a nationwide PROM program in the US is still possible but will need to start at the grass-roots level with like-minded dermatologists sharing insights and working together. Expert consensus groups will need to identify and prioritize optimal PROMs for specific populations of interest before implementing PROMs in a value-based model [69]. The AAD’s DataDerm would provide a great platform to rapidly collect and test the clinical value of specific PROMs on a national scale [57].

9 Conclusions

PROMs offer a quantifiable, reproducible way to measure disease-related concerns such as symptom severity and the impact of skin disease on HRQL and help individualize treatment decisions, monitor treatment success, and set realistic treatment expectations [71]. This overview can assist dermatologists in selecting appropriate PROMs for use in their routine clinical practice. Barriers still exist to routine PROM use in clinical care, but increasing technological advances and broader acceptance by patients of technology’s role in healthcare delivery are overcoming some of these barriers. Capturing similar PROM data across a wide range of clinical practices in the US and worldwide can help dermatologists, policymakers, and payors better appreciate the wide-ranging impact of skin diseases on our patients [20].

References

Institute of Medicine (IOM). Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1.

Magin PJ, Adams J, Heading GS, Pond CD. Patients with skin disease and their relationships with their doctors: a qualitative study of patients with acne, psoriasis and eczema. Med J Aust. 2009;190(2):62–4.

Magin PJ, Pond CD, Smith WT, Watson AB, Goode SM. Correlation and agreement of self-assessed and objective skin disease severity in a cross-sectional study of patients with acne, psoriasis, and atopic eczema. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(12):1486–90.

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197–8.

Baumhauer JF. Patient-reported outcomes—are they living up to their potential? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):6–9.

Reddy A, Fihn SD, Liao JM. The VA MISSION Act—creating a center for innovation within the VA. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(17):1592–4.

Kocher KE, Ayanian JZ. Flipping the script—a patient-centered approach to fixing acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):915–7.

Warraich HJ, Meier DE. Serious-illness care 2.0—meeting the needs of patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2492–4.

Saloner B, Stoller KB, Alexander GC. Moving addiction care to the mainstream—improving the quality of buprenorphine treatment. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):4–6.

Calvert MJ, O’Connor DJ, Basch EM. Harnessing the patient voice in real-world evidence: the essential role of patient-reported outcomes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(10):731–2.

Blauvelt A, Wu JJ, Armstrong A, Menter A, Liu C, Jacobson A. Importance of complete skin clearance in psoriasis as a treatment goal: implications for patient-reported outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(5):487–92.

Secrest AM, Hopkins ZH, Frost ZE, Taliercio VL, Edwards LD, Biber JE, et al. Quality of life assessed using Skindex-16 scores among patients with acne receiving isotretinoin treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;8: e202330.

Crowe M, Lott S. Assessing outcomes like a PRO: how pharmacies can use patient-reported outcomes to better manage patients. 2014. https://www.pharmacist.com/article/assessing-outcomes-pro-how-pharmacies-can-use-patient-reported-outcomes-better-manage. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Greenhalgh J, Gooding K, Gibbons E, Dalkin S, Wright J, Valderas J, et al. How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018;2:42.

Lizée T, Basch E, Trémolières P, Voog E, Domont J, Peyraga G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of web-based patient-reported outcome surveillance in patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(6):1012–20.

Nixon NA, Spackman E, Clement F, Verma S, Manns B. Cost-effectiveness of symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment. J Cancer Policy. 2018;15:32–6.

Chren M-M. Measurement of vital signs for skin diseases. J Investig Dermatol. 2005;125(4):viii–ix.

Secrest AM, Chren MM. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes as a vital sign for dermatologic clinical care and clinical investigations. J Investig Dermatol. 2022;142(6):1529–1532.

Finlay AY, Salek MS, Abeni D, Tomas-Aragones L, van Cranenburgh OD, Evers AW, et al. Why quality of life measurement is important in dermatology clinical practice: an expert-based opinion statement by the EADV Task Force on Quality of Life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):424–31.

Chren M-M. Understanding research about quality of life and other health outcomes. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3(6):312–6.

Kroenke K, Monahan PO, Kean J. Pragmatic characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures are important for use in clinical practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(9):1085–92.

HealthMeasures. PROMIS. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

HealthMeasures. Validation. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/measure-development-research/validation. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

PROMIS scoring manual—itch. 2018. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Itch_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Silverberg JI, Hinami K, Trick WE, Cella D. Itch in the general internal medicine setting: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and quality-of-life effects. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(6):681–90.

HealthMeasures. PROMIS measures and conditions. https://www.peprconsortium.org/promis-measures-and-conditions. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Paller A. Asthma and atopic dermatitis validation of PROMIS pediatric instruments. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03051347. 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03051347. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Rothrock NE, Kaat AJ, Vrahas MS, O’Toole RV, Buono SK, Morrison S, et al. Validation of PROMIS physical function instruments in patients with an orthopaedic trauma to a lower extremity. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(8):377–83.

Hung M, Stuart AR, Higgins TF, Saltzman CL, Kubiak EN. Computerized adaptive testing using the PROMIS Physical Function Item Bank Reduces test burden with less ceiling effects compared with the short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment in orthopaedic trauma patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(8):439–43.

Nolte S, Coon C, Hudgens S, Verdam MGE. Psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS® Depression Item Bank: an illustration of classical test theory methods. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3(1):46.

Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Maihoefer CC, Lawrence SM. Validation of the depression item bank from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) in a three-month observational study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;56:112–9.

Chren M-M, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Investig Dermatol. 1996;107(5):707–13.

Aghaei S, Sodaifi M, Jafari P, Mazharinia N, Finlay AY. DLQI scores in vitiligo: reliability and validity of the Persian version. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:8.

He Z, Lu C, Basra MK, Ou A, Yan Y, Li L. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) in 851 Chinese patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(1):109–15.

Shikiar R, Bresnahan BW, Stone SP, Thompson C, Koo J, Revicki DA. Validity and reliability of patient reported outcomes used in Psoriasis: results from two randomized clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):53.

HealthMeasures. Item response theory (IRT). http://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=134&Itemid=938. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Item response theory. https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/item-response-theory. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

HealthMeasures. Computer adaptive tests (CATs). http://www.healthmeasures.net/resource-center/measurement-science/computer-adaptive-tests-cats. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Rai SK, Yazdany J, Fortin PR, Aviña-Zubieta JA. Approaches for estimating minimal clinically important differences in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):143.

Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, Sen S, Landefeld CS. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Investig Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351–7.

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–92.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(1):81–7.

Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33.

Gaufin M, Hess R, Hopkins ZH, Biber JE, Secrest AM. Practical screening for depression in dermatology: using technology to improve care. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):786–7.

HealthMeasures. List of adult measures. 2018. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/list-of-adult-measures. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, Backett EM, Williams J, Papp E. A quantitative approach to perceived health status: a validation study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1980;34(4):281–6.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–6.

Cardiff University School of Medicine. Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index. https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/medicine/resources/quality-of-life-questionnaires/childrens-dermatology-life-quality-index. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5(2):105–10.

Taliercio VL, Snyder AM, Biggs AM, Kean J, Hess R, Duffin KC, et al. Clinicians' perspectives on the integration of electronic patient-reported outcomes into dermatology clinics: a qualitative study. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(6):1719–1725.

University of Nottingham Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology. POEM–Patient Oriented Eczema Measure. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/resources/poem.aspx. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. JAMA Dermatol. 2004;140(12):1513–9.

Rolstad S, Adler J, Rydén A. Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2011;14(8):1101–8.

Hernar I, Graue M, Richards D, Strandberg RB, Nilsen RM, Tell GS, et al. Electronic capturing of patient-reported outcome measures on a touchscreen computer in clinical diabetes practice (the DiaPROM trial): a feasibility study. Pilot Feasib Stud. 2019;5:29.

Swerlick RA, Zhang C, Patel A, Chren MM, Chen S. The Skindex-Mini: a streamlined quality of life measurement tool suitable for routine use in clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(2):510–2.

Abuabara K, Asgari MM, Chen SC, Dellavalle RP, Kalia S, Secrest AM, et al. How data can deliver for dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(2):400–2.

Secrest AM, Chren M-M, Hopkins ZH, Chen SC, Ferris LK, Hess R. Benefits to patient care of electronically capturing patient-reported outcomes in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4):826–7.

Secrest AM. Examples of how PROs have changed patient care in dermatology. https://www.dermproconsortium.org/pro-examples. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Secrest AM. List of dermatology patient-reported outcomes (PROs). https://www.dermproconsortium.org/pro-list. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, Elliott TE, Greenhalgh J, Halyard MY, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–14.

COSMIN initiative. About the initiative. https://www.cosmin.nl/about/. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Campbell N, Ali F, Finlay AY, Salek SS. Equivalence of electronic and paper-based patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(8):1949–61.

Campagna M, Naka F, Lu J. Teledermatology: an updated overview of clinical applications and reimbursement policies. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(3):176–9.

Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(2):13.

Armstrong AW, Chambers CJ, Maverakis E, Cheng MY, Dunnick CA, Chren MM, et al. Effectiveness of online vs in-person care for adults with psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183062.

Squitieri L, Bozic KJ, Pusic AL. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in value-based payment reform. Value Health. 2017;20(6):834–6.

Ehlers AP, Khor S, Cizik AM, Leveque JA, Shonnard NS, Oskouian RJ, et al. Use of patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction for quality assessments. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(10):618–22.

Gensheimer SG, Wu AW, Snyder CF. Oh, the places we’ll go: patient-reported outcomes and electronic health records. Patient. 2018;11(6):591–8.

NHS England. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/proms/. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Secrest AM, Hopkins ZH, Frost ZE, Taliercio VL, Edwards LD, Biber JE, et al. Quality of life assessed using skindex-16 scores among patients with acne receiving isotretinoin treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(10):1–9.

Kotter JP, Schlesinger LA. Choosing strategies for change. Harv Bus Rev. 1979;57(2):106–14.

Carlisle RP, Flint ND, Hopkins ZH, Eliason MJ, Duffin KC, Secrest AM. Administrative burden and costs of prior authorizations in a dermatology department. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(10):1074–8.

Barbieri JS, Gelfand JM. Patient-reported outcome measures as complementary information to clinician-reported outcome measures in patients with psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021.

Armstrong AW, Ford AR, Chambers CJ, Maverakis E, Dunnick CA, Chren MM, et al. Online care versus in-person care for improving quality of life in psoriasis: a randomized controlled equivalency trial. J Investig Dermatol. 2019;139(5):1037–44.

Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, Tejasvi T, Farah R, Secrest AM, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(5):595–7.

Hopkins ZH, Han G, Tejasvi T, Deda LC, Goldberg R, Kennedy J, et al. Teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and future directions. Cutis. 2022;109(1):12–3.

Secrest AM, Hess R. Patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice in autoimmune bullous disease patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):AB216.

EuroQol. EQ-5D instruments. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-3L Health Questionnaire. 1990. https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Sample_UK__English__EQ-5D-3L_Paper_Self_complete.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-Y Health Questionnaire. 2008. https://euroqol.org/docs/Sample_UK__English__EQ-5D-Y_Paper_Self_complete.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-5L Health Questionnaire. 2009. https://euroqol.org/docs/Sample_UK__English__EQ-5D-5L_Paper_Self_complete.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-3L user guide. 2018. https://euroqol.org/docs/EQ-5D-3L-User-Guide.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–4.

Hunt SM, McEwen J. The development of a subjective health indicator. Sociol Health Ill. 1980;2(3):231–46.

Bushnik T. Nottingham Health Profile. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 1797–8.

Ebrahim S, Barer D, Nouri F. Use of the Nottingham Health Profile with patients after a stroke. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986;40(2):166–9.

PROMIS Global scoring manual. 2017. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Global_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). http://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=1653&itemtype=document. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

El Fakir S, Baybay H, Bendahhou K, Obtel M, Benchat L, Mernissi FZ, et al. Validation of the Skindex-16 questionnaire in patients with skin diseases in Morocco. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25(2):106–9.

Chren M-M, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(11):1433–40.

Girman CJ, Hartmaier S, Thiboutot D, Johnson J, Barber B, DeMuro-Mercon C, et al. Evaluating health-related quality of life in patients with facial acne: development of a self-administered questionnaire for clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(5):481–90.

Merck & Co., Inc. Acne-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (Acne-QoL) Manual & Interpretation Guide. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc; January 2003. http://www.anzctr.org.au/Steps11and12/376709-(Uploaded-11-01-2019-20-05-40)-Study-related%20document.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Esmann S, Vinding GR, Christensen KB, Jemec GBE. Assessing the influence of actinic keratosis on patients’ quality of life: the AKQoL questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):277–83.

Weller K, Magerl M, Peveling-Oberhag A, Martus P, Staubach P, Maurer M. The Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL)—assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2016;71(8):1203–9.

Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, Tohme N, Martus P, Krause K, et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy. 2012;67(10):1289–98.

University of Nottingham. POEM for self-completion. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/documents/methodological-resources/poem-for-self-completion.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

University of Nottingham. POEM for proxy completion (e.g by parent). https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/documents/methodological-resources/poem-for-proxy-completion.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

University of Nottingham. POEM for self-completion and/or proxy completion. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/documents/methodological-resources/poem-for-self-completion-or-proxy-completion.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

University of Nottingham. POEM for self-completion. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/documents/methodological-resources/poem-for-self-completion-chinese.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Barbarot S, Taieb A, Diepgen T, Ambonati M, Durosier V, et al. Patient-Oriented SCORAD: a self-assessment score in atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2009;218(3):246–51.

PO-Scorad Demo. Poscorad Demo EN [Video]. 2013. https://www.fondation-dermatite-atopique.org/en/healthcare-professionals-space/po-scorad. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

PO-SCORAD sheet. https://www.fondation-dermatite-atopique.org/sites/default/files/PO_Scorad_Patients_Feuillet-GB.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(1):104–10.

Cardiff University School of Medicine. Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/medicine/resources/quality-of-life-questionnaires/infants-dermatitis-quality-of-life-index. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Abramova L, Yeung J, Chren MM, Chen S. Rosacea quality of life index (RosaQol) [abstract P45]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(3)(suppl):P12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2003.10.051.

Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Logan BR, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. The skin cancer index: clinical responsiveness and predictors of quality of life. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(3):399–405.

Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Logan BR, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. Validation of a quality-of-life instrument for patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8(5):314–8.

Vinding GR, Christensen KB, Esmann S, Olesen AB, Jemec GBE. Quality of life in non-melanoma skin cancer—the skin cancer quality of life (SCQoL) questionnaire. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(12):1784–93.

Burdon-Jones D, Gibbons K. The Skin Cancer Quality of Life Impact Tool (SCQOLIT): a validated health-related quality of life questionnaire for non-metastatic skin cancers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(9):1109–13.

Elman S, Hynan LS, Gabriel V, Mayo MJ. The 5-D itch scale: a new measure of pruritus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(3):587–93.

Desai NS, Poindexter GB, Monthrope YM, Bendeck SE, Swerlick RA, Chen SC. A pilot quality-of-life instrument for pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2):234–44.

Stumpf A, Pfleiderer B, Fritz F, Osada N, Chen SC, Ständer S. Assessment of quality of life in chronic pruritus: relationship between ItchyQoL and Dermatological Life Quality Index in 1,150 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:142–3.

PROMIS scoring manual—depression. 2019. http://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

PROMIS scoring manual social isolation. 2015; http://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

PROMIS scoring manual—pain interference. 2019. http://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS). Instructions. https://www.posas.org/the-posas/instruction/. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

PROMIS scoring manual sleep disturbance. 2019. http://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

PROMIS scoring manual—sleep-related impairment. 2019. http://www.healthmeasures.net/search-view-measures. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

Ms. Snyder, Mr. Flint, Mr. Edwards, and Drs. Cizik, Kean, Hess, Swerlick, and Secrest report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Chen receives royalties for quality-of-life instruments from for-profit entities that license these instruments. Dr. Chren shares copyrights for some of the Skindex family of quality-of-life tools; she receives payments from the University of California for their use by for-profit companies. Dr. Ferris has received funding for research from AbbVie, Arcutis, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, BMS, DermTech, Castle Biosciences, Galderma, and Leo and has received compensation for consulting and/or speaking from Pfizer, BMS, AbbVie, Arcutis, Dermavant, DermTech, Sun Pharma, and Janssen. Dr. Secrest is funded in part by a Dermatology Foundation Public Health Career Development Award.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate and/or publish

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed content ideas/revisions.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Snyder, A.M., Chen, S.C., Chren, MM. et al. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures and Their Clinical Applications in Dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol 24, 499–511 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-023-00758-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-023-00758-8