Abstract

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease defined by the presence of non-caseating granulomas. It can affect a number of organ systems, most commonly the lungs, lymph nodes, and skin. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis can impose a significant detriment to patients’ quality of life. The accepted first-line therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis consists of intralesional and oral corticosteroids, but these can fail in the face of resistant disease and corticosteroid-induced adverse effects. Second-line agents include tetracyclines, hydroxychloroquine, and methotrexate. Biologics are an emerging treatment option for the management of cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their role in management is not well-defined. In this article, we reviewed the currently available English-language publications on the use of biologics in managing cutaneous sarcoidosis. Although somewhat limited, the data in published studies support the use of both infliximab and adalimumab as third-line treatments for chronic or resistant cutaneous sarcoidosis. There were also scattered reports of etanercept, rituximab, golimumab, and ustekinumab being utilized as third-line agents with varying degrees of success. Larger and more extensive investigations are required to further assess the adverse effect profile and optimal dosing for managing cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

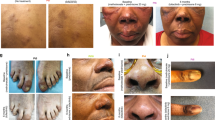

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease defined by the presence of non-caseating granulomas, with the most commonly involved organs being the lungs, lymph nodes, and skin [1]. The most common manifestations of cutaneous sarcoidosis include papules and erythema nodosum, which typically confer a more favorable prognosis [2, 3]. Other common cutaneous manifestations include lupus pernio, plaques, and subcutaneous lesions, which are found in more chronic systemic disease courses [3]. Lupus pernio is characterized by chronic, violaceous, telangiectatic, indurated lesions on the nose and cheeks that often cause disfigurement and can be recalcitrant to treatment with systemic corticosteroids [3].

The treatment choice for cutaneous sarcoidosis is mostly driven by clinical experience and anecdotal information rather than the evidence-based guidelines, due to a paucity of high-quality studies available in the literature [4]. The most common and first-line treatment options include intralesional or systemic corticosteroids [3]. While high potency topical corticosteroids have been anecdotally utilized for localized disease, this modality may not be efficacious due to cutaneous lesions extending deeply [5,6,7]. For rapidly progressive or highly disfiguring skin manifestations, systemic corticosteroids remain the initial choice in treatment despite the adverse effects associated with long-term use. Corticosteroid-sparing agents used in treatment include methotrexate, antimalarials, pentoxifylline, apremilast, tetracyclines, isotretinoin, leflunomide, thalidomide, and cyclosporine [8]. However, some cases of sarcoidosis remain refractory to both corticosteroid and corticosteroid-sparing agents, creating a need for alternative therapeutic options.

Recently, off-label use of various biologics has been utilized to manage sarcoidosis. This literature review aims to summarize and analyze the evidence available on the use and response to biologics in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using various scoring tools (Table 1). The end goal was to provide a better understanding of the role of biologics in cutaneous sarcoidosis and provide recommendations for clinicians on how to utilize biologics in clinical practice based on the efficacy and safety profile.

2 Methods

We conducted a PubMed and Cochrane Library search for English-language publications that address cutaneous sarcoidosis and treatment with certain biologics or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Search terms used include a combination of the following: tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors, adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, certolizumab, golimumab, anakinra, IVIG, pitrakinra, secukinumab, and pascolizumab in combination with sarcoidosis and cutaneous sarcoidosis. Literature from 2001 to 2018 was considered for inclusion in this review. No publications on certolizumab, anakinra, secukinumab, pitrakinra, pascolizumab, tocilizumab, or IVIG that met our criteria were identified regarding the treatment of cutaneous sarcoid.

3 Results

3.1 Infliximab

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal human-murine antibody that inhibits TNFα and is currently approved by the US FDA to treat various immune-mediated diseases. Infliximab is the most extensively reported biologic for off-label treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. A total of 17 case reports and case series, two articles stemming from a single prospective, blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, and four retrospective studies were reviewed.

Several different skin scoring tools were utilized to monitor therapeutic effects. Investigations by Heidelberger et al., Jamilloux et al., and Judson et al. studied the effects of infliximab using the extrapulmonary Physician Organ Severity Tool (ePOST) [9,10,11], a tool developed in 2008 that examined the state of sarcoidosis involvement in 17 extrapulmonary organs, including skin (Table 1). Two recent French studies utilizing ePOST found that infliximab administration resulted in a significant reduction in cutaneous ePOST scores [9, 10]. Interestingly, administration in 40 of 46 cases from a national French database investigating the use of anti-TNF inhibitors in sarcoidosis showed increasing efficacy from 3 to 12 months in the reduction of nodules, but not with other lesions such as lupus pernio or plaques [9]. Disease relapse was reported both during (35%) and after discontinuation of treatment (44%) at 18 months. A randomized controlled study by Judson et al. also reported a reduction in skin-specific ePOST scores in the infliximab-treated group versus placebo, but statistical significance was not achieved due to the low sample size [11].

The Lupus Pernio Physician Global Assessment (LuPGA) and Sarcoidosis Activity and Severity Index (SASI) are two scoring tools that have been used by Baughman et al. on a subset of 19 patients with lupus pernio who were treated with either placebo 3 mg/kg or infliximab 5 mg/kg [12]. After 24 weeks, 44% of patients taking the 5 mg/kg dose achieved near or complete clearance of lesions according to the LuPGA, compared with 20% of patients taking placebo and none of the patients taking the 3 mg/kg dose. In 2015, Baughman et al. used SASI, a validated tool that scores individual facial lesions in four quadrants by different factors: erythema, induration, desquamation, and percentage of the total area involved, to show that infliximab-treated patients exhibited a significant reduction in scores for induration and desquamation at 24 weeks of treatment in a dose-dependent manner compared with placebo [13].

Quality-of-life tools have also been used to interpret patients’ self-perceived improvement while taking infliximab. Pre- and post-treatment quality of life was assessed using the Short Form-36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36), which showed improved self-reported physical and mental health in infliximab-treated patients compared with placebo [13].

In 2009, Stagaki et al. reported the largest study on lupus pernio to date [14]. Notably, all infliximab-treated patients in the study did not respond to a previous alternate treatment. Patients were assessed by a single investigator using clinical photographs. Response to therapy was judged according to the global difference and change in the percentage of facial surface that was involved with lupus pernio lesions and classified into one of the following five categories: (1) resolution: complete response with disappearance of lesions; (2) near resolution: minimal active lesions, plus possible hyperpigmentation/ hypopigmentation or fibrosis; (3) improvement: partial response to treatment; (4) no change: stable lesions; and (5) worse: extension of lesions. Of 116 total treatment courses, infliximab administered at 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6, and then every 6 weeks, resulted in a statistically significant response in 77% of cases within 5 months.

3.1.1 Case Reports/Series

An additional 41 patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with infliximab were reported in case reports and case series [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] (Table 2). In summary, the cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis in the literature that reportedly used infliximab were primarily chronic disease or disease that had been refractory to other treatments. In most cases, infliximab resulted in either partial or complete response of otherwise recalcitrant cutaneous disease ranging from scarring alopecia, lupus pernio, plaques, and nodules [16, 20, 23]. A female patient receiving continuous infliximab therapy reportedly remained disease-free after 3.5 years [25]. Because the guidelines for management are ill-defined, most patients were receiving a combination of infliximab with other immunosuppressive agents such as oral corticosteroids, although the specific treatment regimens were unclear in many reports [16]. For numerous cases where patients initially relied on high doses of corticosteroids to manage their disease, initiating infliximab allowed them to eventually taper down their corticosteroid therapy and avoid associated adverse effects [20, 31]. However, prednisone tapering had also reportedly caused disease relapse in a patient taking infliximab, which was reversed by increasing his infliximab dose from 5 to 10 mg/kg, resulting in stabilization of his disease [20].

3.1.2 Infliximab Dosing

Infliximab dosing ranged from 3 to 10 mg/kg, with intervals ranging from every 3 to every 10 weeks [18] (Table 2). Most patients were administered an initial dose of 5 mg/kg, which has been prescribed for other inflammatory disorders such as Crohn’s disease and psoriasis [18]. According to the reports in the literature, most patients initially respond within 5 months of treatment, but the long-term effects of infliximab therapy have shown wide variability in terms of response.

In one case, a patient taking 5 mg/kg at 8-week maintenance intervals was able to discontinue infliximab and be disease-free 6 months later after taking methotrexate 20 mg/week and hydroxychloroquine 100 mg daily, but many other patients experienced disease relapse [23, 27]. The total time range reported for relapse ranged between 3 weeks and 15 months after infliximab discontinuation, with no clear relationship to dosing. One case series of three patients who received infliximab 3 mg/kg at 8-week intervals reported relapse within 6–8 months after discontinuation [18]. In another case series, patients who were treated with the same dose (5 mg/kg at 6-week maintenance intervals) experienced different results, with some remaining in remission for 2 years after discontinuation, while those who relapsed did so within 2–4 months after discontinuation [29].

Increasing the dosage has been efficacious in some patients who were originally unresponsive or relapsed during corticosteroid tapering [13, 18, 20, 24, 27, 28]. Additionally, shortening maintenance intervals has resulted in higher trough levels than solely increasing the dose along with improved efficacy [24, 28]. Low-dose methotrexate with treatment, or replacing infliximab with methotrexate for maintenance, has also been suggested to improve efficacy, although no clinical trials exist to support this data [21].

3.1.3 Infliximab Safety Profile

Numerous reports exist of adverse effects arising during infliximab treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis, and are similar to those reported in patients in the treatment of other diseases. Infection was the most common adverse effect, and combined corticosteroid use with infliximab was associated with a higher risk of infections [9].

A drug safety registry with data from 14 public hospitals in Spain recorded the use of TNFα antagonists used to treat sarcoidosis over 11 years [32]. The most common adverse effects found were infections and ocular manifestations. One death was attributed to disease progression. A multi-institutional retrospective study in France found that 42% of all patients being treated for chronic sarcoidosis contracted infections, with the most serious cases being Pneumocystis jiroveci and pseudomonal pneumonia. Two complications directly attributed to infliximab were acute leukoencephalopathy and diffuse hypoxemic interstitial pneumonitis, which resolved with discontinuation of infliximab [33]. One patient developed a hypercoagulable state with anticardiolipin antibodies [34].

Infliximab may also cause local injection site reactions. For mild urticarial reactions, antihistamines may be sufficient to allow continuation of therapy [18]. Psoriasis and blepharitis have also been reported [21]. One case of symptomatic hypothyroidism was attributed to infliximab in a 47-year-old male with lupus pernio [22]. Treatment with levothyroxine resolved the symptoms, and infliximab infusions were continued. Development of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) may occur and may be of unknown significance, with no adverse changes in liver or kidney functions, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), or rheumatoid factor [18].

3.2 Adalimumab

Adalimumab is an anti-TNF human recombinant IgG1 monoclonal antibody that has been increasingly utilized in cutaneous sarcoidosis. Only one clinical trial has been conducted to date that studied adalimumab therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Using the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score (Table 1), area and volume of lesions, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score, Patient Global Evaluation (PGE), and Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (SHQ), a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adalimumab treatment over a 24-week period [8]. For the first 12 weeks, 15 patients received weekly injections of either adalimumab 40 mg (n = 10) or placebo (n = 5). Next, all patients received open-label adalimumab (n = 13) for the following 12 weeks. Primary findings were a PGA score of ≤ 2 in 50% of the adalimumab group compared with 20% of the placebo group, and a significant reduction in target lesion area. DLQI was significantly improved at the end of the open-label phase, but SHQ showed no significant difference. Eight weeks after discontinuation of the open-label phase, the number of patients who had clearance or marked improvement of lesions reduced from eight to four, while the number of patients who had at least moderate improvement reduced from ten to six. Target lesion area also increased compared with immediately post-treatment.

3.2.1 Case Reports/Series

An additional eight case reports and one case series reporting on adalimumab therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis were found (Table 3) [28, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. In all cases, patients responded to either adalimumab monotherapy or adalimumab in combination with one or more agents, such as methotrexate and intralesional corticosteroid. Improved cutaneous disease was noted as early as 2 weeks from initiation of adalimumab.

3.2.2 Adalimumab Dosing

The most common dosage for adalimumab was 40 mg, either weekly or every 2 weeks, with the weekly dosing being potentially more efficacious. Four cases initiated adalimumab at a loading dose of 80 mg for either the first dose or for the first few weeks, before reducing to 40 mg every 2 weeks [37, 39, 41, 42]. One case required adjuvant methotrexate and low-dose corticosteroids due to a flare after dose reduction [39]. Additionally, increasing the treatment interval from 2 to 3 weeks resulted in relapse, after which the interval was reduced back to 2 weeks with subsequent remission [36]. Overall, the dosage for optimal therapeutic effect may depend on several factors, such as the severity of disease, the addition of corticosteroids or corticosteroid-sparing medications, and weekly dosing, which can be potentially more efficacious.

3.2.3 Adalimumab Safety Profile

In the literature on cutaneous sarcoidosis that was examined, adalimumab appears to have a relatively safe adverse effect profile. Reported adverse events to adalimumab included headache, musculoskeletal symptoms, pulmonary symptoms, and infections [8]. Of five patients (33%) who developed infections, one suffered a severe case of pneumonia and had to discontinue the trial. Additionally, the patient in the case report by Field et al. was reportedly treated for latent tuberculosis with isoniazid and rifampicin after starting adalimumab therapy due to a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) [39]. No adverse effects were reported in any other case reports. Nonetheless, patients taking adalimumab warrant monitoring due to an increased risk of lymphoma and serious infections, especially if on combination therapy with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants.

3.3 Etanercept

Etanercept is a recombinant fusion protein of two p75 soluble TNFα receptors and the Fc portion of human IgG. Unlike infliximab, which binds both the monomer and trimer forms of soluble TNF, as well as the transmembrane form, etanercept binds only to the trimer form of soluble TNFα and has less avidity to the transmembrane form. Due to this differing mechanism, it is important to compare etanercept with infliximab and adalimumab.

3.3.1 Etanercept Case Reports

Regarding efficacy, there are two cases in the literature that have reported successful use of etanercept in refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis, with patients experiencing a marked improvement in 6–8 weeks [43, 44] (Table 4). However, when compared with other TNFα inhibitors, etanercept has been reported to be less efficacious, with two reports of treatment failures with etanercept, but positive outcomes after switching to infliximab or adalimumab [27, 39]. These findings are consistent with studies that have reported lackluster results in using etanercept for extracutaneous sarcoidosis [45].

3.3.2 Etanercept Dosing

In terms of dosing, there is no established recommendation. Cases in the literature have reported using either 25 or 50 mg of etanercept administered twice weekly for sarcoidosis with cutaneous involvement. There is no clear trend with regard to safety and efficacy between these two doses as the data on etanercept is limited not only for cutaneous sarcoidosis but for all forms of sarcoidosis.

3.3.3 Etanercept Safety Profile

The examined literature on etanercept for cutaneous sarcoidosis reported a relatively safe drug profile, with only one patient having to stop etanercept and start broad-spectrum antibiotics after developing cellulitis 6 months into treatment [44]. After the patient recovered, etanercept was continued at the same dosage without recurrence. In general, etanercept has been reported to cause an increased risk of infection, development of malignancy, demyelinating diseases, congestive heart failure, and, in rare cases, nasopharyngeal plasmacytoma and intestinal lymphoma [45, 46].

3.4 Comparison of Golimumab Versus Ustekinumab for Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

Golimumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds TNFα with high affinity and specificity and is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Ustekinumab is a human monoclonal antibody to the p40 subunit of interleukin (IL)-12 and -23 and is approved for treating psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and Crohn’s disease [47].

A single randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of golimumab and ustekinumab in chronic sarcoidosis [47]. Results were measured using the Skin Physician’s Global Assessment (SPGA) and SASI scoring tools. Patients also completed various patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires to assess subjective improvement. Overall, 173 patients were randomized into groups, depending on disease involvement—lung, skin, or both.

The dose for golimumab was 200 mg, followed by 100 mg every 4 weeks, and for ustekinumab, the dose was 180 mg, followed by 90 mg every 8 weeks. Neither biologic resulted in a statistically significant improvement in disease burden or PRO scores compared with placebo after 28 weeks. Golimumab resulted in non-significant improvements in SPGA and SASI scores. Notably, patients with lower body mass index (BMI) tended to respond better to golimumab (statistically non-significant), suggesting the possibility that the doses used in the study were subtherapeutic.

3.4.1 Reported Safety Profile

Both biologic agents demonstrated safety profiles comparable to placebo, with 15.5% total serious adverse events reported. Three cases of infections were reported with golimumab use, with the most serious being tuberculosis. One mortality occurred in a patient 5 months after receiving a single dose and being subsequently withdrawn from the study for dyspnea. Other common events in the golimumab group were cough, arthralgia, fatigue, and dyspnea. Adverse events in the ustekinumab group included cough, fatigue, headaches, or upper respiratory infections. One mortality from acute respiratory failure 5 months after 12 weeks of ustekinumab was reported.

3.5 Rituximab

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the CD20 antigen of B lymphocytes; some studies have reported off-label use for sarcoidosis. One report describes a 50-year-old woman with neuro and cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with the rheumatoid arthritis protocol (two doses of rituximab 1 g 2 weeks apart) [48]. The patient was then continued on rituximab 1 g every 6 months for 2 years and experienced complete resolution of her cutaneous lesions.

A 44-year-old male with lupus pernio who was a poor candidate for anti-TNF therapy was started on rituximab 1 g per month for 3 months with adjuvant hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. This combination was initially effective but the patient relapsed after 4 months. Three additional doses of rituximab with mycophenolate mofetil provided mild improvement, but after 8 months, the disease and symptoms began worsening [49]. The same series described a 29-year-old female with multisystemic sarcoidosis who had been previously responsive to infliximab 5 mg/kg every 6–8 weeks and adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, as well as methotrexate and deflazacort therapy. Due to disease relapse, the patient was started on the lymphoma protocol (rituximab 375 mg/m2 weekly) and cyclophosphamide, but developed vision loss and no improvement of her skin lesions. The patient finally improved after restarting infliximab. The authors hypothesized that although rituximab was ineffective at inhibiting sarcoidosis activity, its anti-CD20 properties may have disturbed B-cell-dependent resistance to infliximab, leading to the effectiveness upon reintroduction [49].

Overall, rituximab appears to have mixed efficacy as one case had resolution of cutaneous sarcoidosis, whereas two other cases experienced minimal improvement. On the other hand, such a small number of reports may not allow for definitive conclusions regarding its role in cutaneous sarcoidosis. Further research will be needed, with a focus on optimizing rituximab dosing as well as exploring its indirect therapeutic properties through enhancement of TNFα inhibitors such as infliximab. Presently, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of rituximab for patients with recalcitrant disease who have contraindications to anti-TNFα therapy.

4 Discussion

Although still limited, there are an increasing number of publications on the use of biologics in cutaneous sarcoidosis. The overwhelming majority of publications reviewed were on TNFα inhibitors, particularly infliximab and adalimumab. The remainder included scattered reports utilizing etanercept and rituximab and one trial investigating golimumab, and ustekinumab.

4.1 Efficacy of Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α Agents: Infliximab, Adalimumab, Etanercept

Of the biologics reviewed, infliximab has the largest volume of reported efficacy in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis, particularly lupus pernio, a subtype that is difficult to treat and can cause facial disfigurement. Infliximab has also shown efficacy in sarcoidosis-associated alopecia and rapidly progressive plaques [16, 23]. Judson et al. showed that adding infliximab to the treatment of multisystem sarcoidosis already stabilized by corticosteroids resulted in a further reduction of ePOST scores. This suggests that infliximab can provide additional therapeutic benefits beyond that of first-line immunosuppression [11]. The limited studies on adalimumab also suggest relative efficacy in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis. Although adalimumab was able to significantly reduce lesion area and volume in a double-blinded, placebo-controlled study, its effect on the PGA score was not significant, possibly due to the small sample size [8]. In comparison, etanercept, which is also a TNFα inhibitor, appears to lack the same efficacy as infliximab and adalimumab [43, 44], which is consistent with studies that have reported on the lackluster results of etanercept in treating extracutaneous sarcoidosis [45].

The significant corticosteroid-sparing properties of infliximab and adalimumab have either been shown in larger observational studies or described in case reports. For adalimumab, numerous cases reported on a similar corticosteroid-sparing effect in which patients were able to taper off corticosteroids or reduce their dose to < 10 mg/day without relapse [36]. This can potentially allow patients to lower the risk of adverse effects of long-term corticosteroid use, such as hypertension, weight gain, diabetes, and fractures from osteoporosis. Additionally, it has also been beneficial in patients who experience adverse effects to corticosteroid-sparing agents. Patients who discontinued thalidomide after initiating infliximab experienced a reduction in peripheral neuropathy, and patients taken off methotrexate benefited from a reduction in leukopenia and abnormal liver function tests [20].

The different assessments used to evaluate lesions should be taken into account when comparing outcomes. For example, ePOST does not specifically account for facial involvement, unlike LuPGA. Therefore, a study that utilized ePOST to assess different types of sarcoid skin lesions found that only nodular lesions were significantly reduced as opposed to plaques or lupus pernio [9]. However, multiple other studies support the use of infliximab in the latter two lesion types [15, 16, 26, 31]. Additionally, it is important for clinicians to weigh patient satisfaction against objective outcomes due to the potential of cutaneous sarcoidosis to cause disfigurement and detriment to psychological health and quality of life. Self-reported scoring systems include the DLQI, a tool for dermatological studies, the SF-36, which incorporates both a mental health and physical component, SHQ, and visual analog scale scores. There were reports of improved DLQI scores after treatment with infliximab and adalimumab [8, 13, 23, 37]. Infliximab also improved SF-36 scores and adalimumab improved SHQ and visual analog scores [8, 21, 23, 37].

Overall, both infliximab and adalimumab appear to be promising alternatives for refractory or chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis that are generally well-tolerated and efficacious. To prevent relapse, some cases may require long-term biologic therapy, the addition of corticosteroids, or an adjuvant immunosuppressive agent. Due to the paucity of data and mixed reports regarding efficacy, etanercept would be less likely to be recommended.

4.2 Shortcomings

The most notable shortcomings of infliximab and adalimumab were disease relapse during corticosteroid tapering or after discontinuation [8, 21]. Clinicians should be aware that patients may require long-term maintenance or be closely followed for recurrence. Long-term therapy can be difficult due to the need for monitored parenteral administration in a healthcare facility in the case of infliximab. Compared with infliximab, adalimumab can be self-administered, which can be a significant factor when deciding on a treatment regimen.

One of the most clinically relevant adverse reactions to using anti-TNFα is an increased susceptibility to infections. However, the long-term use of anti-TNFα should be weighed against long-term corticosteroid use, which also poses a high risk for infections as well as numerous other adverse effects. Therefore, their corticosteroid-sparing properties must be taken into account when considering treatment.

Although rare, a notorious concern against using anti-TNFα agents is the potential for reactivation of underlying tuberculosis. Additionally, there have also been multiple reports of all TNFα inhibitors causing a paradoxical sarcoid-like reaction in patients being treated for other immunological conditions, and resolved after terminating treatment [50,51,52]. Thus, anti-TNFα biologics remain third-line agents and necessitate appropriate screening before initiating treatment [21]. Future larger randomized trials would help in determining the most efficacious dosages and treatment durations, and allow further delineation of the drugs’ adverse effect profiles in the cutaneous sarcoidosis population.

4.3 TNFα Inhibitor Costs

When evaluating treatment options, the cost of administering TNFα inhibitors should be considered. In 2012, Bonafede et al. found infliximab to be the most expensive TNFα inhibitor, with an average cost of US$24,000 a year per patient [53]. Additionally, these drugs lack an FDA indication for sarcoidosis, creating a barrier for insurance coverage. Notably, Wanat and Rosenbach reported that insurance covered the treatment of five patients after they were sent a letter of medical necessity documenting the alternative medications attempted [28]. Thus, appropriate documentation of failed treatments can increase the likelihood of obtaining insurance coverage.

4.4 Treatment Options Affected by Sarcoid Type

Ultimately, the response to infliximab and other biologics appears unpredictable because similar dosages resulted in relapse in some patients and remission in others [20, 28]. Various markers of inflammation (CRP, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and positron emission tomography scan positivity) have been reportedly useful in monitoring response to infliximab [54, 55]. A case series by Crouser et al. supported the idea that different subtypes of sarcoidosis may also play a role in the degrees of treatment efficacy. They observed that a refractory phenotype of sarcoidosis with CD4+ lymphopenia responded well to infliximab, with a resulting increase in CD4+ counts [17]. This subtype may have heightened sensitivity to TNFα inhibitors whose mechanism may alter the function of regulatory T cells. In addition to monitoring markers of inflammation, evaluating CD4+ T-cell levels prior to management could potentially play a role in treatment considerations. It is possible that different treatment outcomes could be explained by the possibility of sarcoidosis being encompassed by multiple subtypes despite overlapping clinical and histopathological features. Future research on this topic is necessary to further delineate how to select the best treatment approach.

4.5 Overall Recommendations

Because of the volume of literature and supportive results, we currently favor the use of infliximab and adalimumab for cases of chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis refractory to corticosteroid-sparing agents. In the case of disease relapse or further resistance, we recommended either increasing the dosage or shortening maintenance intervals before attempting alternate treatments. The use of etanercept and rituximab are both underreported for cutaneous sarcoidosis, and scattered case reports have shown mixed efficacy. Golimumab and ustekinumab were both found to be ineffective at significantly improving cutaneous sarcoidosis. Although it is possible the doses used were subtherapeutic, based on the paucity of literature and reported outcomes, we currently do not recommend their use in routine clinical practice.

Finally, it is important for practitioners to be familiar with the possibility of a paradoxical sarcoid reaction when utilizing TNFα inhibitors. There have been multiple reports of TNFα inhibitors causing this reaction in patients being treated for other immunological conditions, and resolved after terminating treatment [50,51,52]. If there are any signs of disease progression after treatment initiation, the agent should be discontinued.

4.6 Future Biologics for Consideration

Although no reports on other biologics used to treat cutaneous sarcoidosis were found in the literature, further investigation is needed in this area with agents that have shown favorable outcomes in extracutaneous sarcoidosis. Tofacitinib and ruxolitinib, oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, were recently reported to result in clinical and histological remission in two patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis refractory to adalimumab and infliximab [56, 57]. These case reports support the role of JAK-STAT signaling in cutaneous sarcoidosis and as a potential avenue for future treatment and disease modulation. IVIG was reportedly beneficial in cases of neurosarcoidosis and sarcoid myopathy, while anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, has been associated with successful management of sarcoidosis alongside TNFα inhibitors [58,59,60]. Tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, has shown efficacy in treating patients with coexisting sarcoidosis and other inflammatory conditions, such as mixed-type multicentric Castleman’s disease and adult-onset Still’s disease [61, 62].

5 Conclusions

Biologics are still a relatively new and underevaluated third-line option for treating cutaneous sarcoidosis refractory to conventional modalities. Consequently, most data are only available through case reports and observational studies. This literature review concludes that infliximab and adalimumab are currently favored over other biologics due to the availability of literature and reported outcomes. We recommend selecting infliximab over adalimumab, particularly in cases of lupus pernio, nodular lesions, or progressive disease. Infliximab and adalimumab both have a similar safety profile, and the most common adverse effects to monitor for are infections and ocular manifestations. Infliximab is only available through parenteral administration, while adalimumab can be self-administered subcutaneously, an important practical consideration when deciding on therapy. Insufficient data exist to recommend the use of etanercept, rituximab, golimumab, or ustekinumab. Further research is necessary to elucidate the potential role of other biologics in future cutaneous sarcoid management, as well as to decipher optimal therapeutic dosages for all agents.

References

Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. Cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(5):699 e1–18 (quiz 717–8).

Petit A, Dadzie OE. Multisystemic diseases and ethnicity: a focus on lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, sarcoidosis and Behcet disease. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(Suppl 3):1–10.

Heath CR, David J, Taylor SC. Sarcoidosis: are there differences in your skin of color patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(1):121 e1–14.

Doherty CB, Rosen T. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Drugs. 2008;68(10):1361–83.

Volden G. Successful treatment of chronic skin diseases with clobetasol propionate and a hydrocolloid occlusive dressing. Acta Dermatovenereol. 1992;72(1):69–71.

Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(3):334–40.

Fetil E, Ozkan S, Ilknur T, Kavukcu S, Kusku E, Lebe B. Sarcoidosis in a preschooler with only skin and joint involvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(5):416–8.

Pariser RJ, Paul J, Hirano S, Torosky C, Smith M. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adalimumab in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):765–73.

Heidelberger V, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Marquet A, Mahevas M, Bessis D, Bouillet L, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents in cutaneous sarcoidosis: a French Study of 46 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(7):681–5.

Jamilloux Y, Cohen-Aubart F, Chapelon-Abric C, Maucort-Boulch D, Marquet A, Perard L, et al. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in refractory sarcoidosis: a multicenter study of 132 patients. Semin Arthr Rheum. 2017;47(2):288–94.

Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U, Flavin S, Lo KH, Kavuru MS, et al. Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: results from a randomised trial. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(6):1189–96.

Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, Judson MA, Costabel U, du Bois R, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(7):795–802.

Baughman RP, Judson MA, Lower EE, Drent M, Costabel U, Flavin S, et al. Infliximab for chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis: a subset analysis from a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;32(4):289–95.

Stagaki E, Mountford WK, Lackland DT, Judson MA. The treatment of lupus pernio: results of 116 treatment courses in 54 patients. Chest. 2009;135(2):468–76.

Baughman RP, Lower EE. Infliximab for refractory sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2001;18(1):70–4.

Mallbris L, Ljungberg A, Hedblad MA, Larsson P, Stahle-Backdahl M. Progressive cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2):290–3.

Crouser ED, Lozanski G, Fox CC, Hauswirth DW, Raveendran R, Julian MW. The CD4+ lymphopenic sarcoidosis phenotype is highly responsive to anti-tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} therapy. Chest. 2010;137(6):1432–5.

Saleh S, Ghodsian S, Yakimova V, Henderson J, Sharma OP. Effectiveness of infliximab in treating selected patients with sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):2053–9.

Chung J, Rosenbach M. Extensive cutaneous sarcoidosis and coexistant Crohn disease with dual response to infliximab: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2014;21(3).

Tuchinda P, Bremmer M, Gaspari AA. A case series of refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis successfully treated with infliximab. Dermatol Ther. 2012;2(1):11.

Sene T, Juillard C, Rybojad M, Cordoliani F, Lebbe C, Morel P, et al. Infliximab as a steroid-sparing agent in refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis: single-center retrospective study of 9 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):328–32.

Cerniglia B, Judson MA. Infliximab-induced hypothyroidism: a novel case and postulations concerning the mechanism. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:216939.

Tu J, Chan J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and infliximab: evidence for efficacy in refractory disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55(4):279–81.

Sweiss NJ, Welsch MJ, Curran JJ, Ellman MH. Tumor necrosis factor inhibition as a novel treatment for refractory sarcoidosis. Arthr Rheum. 2005;53(5):788–91.

Rosen T, Doherty C. Successful long-term management of refractory cutaneous and upper airway sarcoidosis with periodic infliximab infusion. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13(3):14.

Blanco R, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Lopez MA, Fernandez-Llaca H, Gonzalez-Vela MC. Refractory highly disfiguring lupus pernio: a dramatic and prolonged response to infliximab. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(8):e321–2.

Thielen AM, Barde C, Saurat JH, Laffitte E. Refractory chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis responsive to dose escalation of TNF-alpha antagonists. Dermatology. 2009;219(1):59–62.

Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Case series demonstrating improvement in chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis following treatment with TNF inhibitors. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(9):1097–100.

Panselinas E, Rodgers JK, Judson MA. Clinical outcomes in sarcoidosis after cessation of infliximab treatment. Respirology. 2009;14(4):522–8.

Heffernan MP, Anadkat MJ. Recalcitrant cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(7):910–1.

Haley H, Cantrell W, Smith K. Infliximab therapy for sarcoidosis (lupus pernio). Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(1):146–9.

Maneiro JR, Salgado E, Gomez-Reino JJ, Carmona L. Efficacy and safety of TNF antagonists in sarcoidosis: data from the Spanish registry of biologics BIOBADASER and a systematic review. Semin Arthr Rheum. 2012;42(1):89–103.

Jounieaux F, Chapelon C, Valeyre D, Israel Biet D, Cottin V, Tazi A, et al. Infliximab treatment for chronic sarcoidosis: a case series (in French). Revue Mal Respir. 2010;27(7):685–92.

Yee AM, Pochapin MB. Treatment of complicated sarcoidosis with infliximab anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(1):27–31.

Heffernan MP, Smith DI. Adalimumab for treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(1):17–9.

Mirzaei A, Joharimoghadam MM, Zabihiyeganeh M. Adalimumab-responsive refractory sarcoidosis following multiple eyebrow tattoos: a case report. Tanaffos. 2017;16(1):80–3.

Kaiser CA, Cozzio A, Hofbauer GF, Kamarashev J, French LE, Navarini AA. Disfiguring annular sarcoidosis improved by adalimumab. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3(2):103–6.

Philips MA, Lynch J, Azmi FH. Ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to adalimumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(5):917.

Field S, Regan AO, Sheahan K, Collins P. Recalcitrant cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to adalimumab but not to etanercept. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(7):795–6.

Judson MA. Successful treatment of lupus pernio with adalimumab. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(11):1332–3.

Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(12):1305–6.

Hagan CE, Offiah M, Brodell RT, Jackson JD. Chronic verrucous sarcoidosis associated with human papillomavirus infection: improvement with adalimumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4(9):866–8.

Tuchinda C, Wong HK. Etanercept for chronic progressive cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(6):538–40.

Khanna D, Liebling MR, Louie JS. Etanercept ameliorates sarcoidosis arthritis and skin disease. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(8):1864–7.

Utz JP, Limper AH, Kalra S, Specks U, Scott JP, Vuk-Pavlovic Z, et al. Etanercept for the treatment of stage II and III progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003;124(1):177–85.

Papp KA. The safety of etanercept for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(2):245–58.

Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U, Drent M, Gibson KF, Raghu G, et al. Safety and efficacy of ustekinumab or golimumab in patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1296–307.

Bomprezzi R, Pati S, Chansakul C, Vollmer T. A case of neurosarcoidosis successfully treated with rituximab. Neurology. 2010;75(6):568–70.

Cinetto F, Compagno N, Scarpa R, Malipiero G, Agostini C. Rituximab in refractory sarcoidosis: a single centre experience. Clin Mol Allergy. 2015;13(1):19.

Lamrock E, Brown P. Development of cutaneous sarcoidosis during treatment with tumour necrosis alpha factor antagonists. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53(4):e87–90.

Marcella S, Welsh B, Foley P. Development of sarcoidosis during adalimumab therapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52(3):e8–11.

Salvatierra J, Magro-Checa C, Rosales-Alexander JL, Raya-Alvarez E. Acute sarcoidosis as parotid fever in rheumatoid arthritis under anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(7):1346–8.

Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Watson C, Princic N, Fox KM. Cost per treated patient for etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab across adult indications: a claims analysis. Adv Ther. 2012;29(3):234–48.

Keijsers RG, Verzijlbergen JF, van Diepen DM, van den Bosch JM, Grutters JC. 18F-FDG PET in sarcoidosis: an observational study in 12 patients treated with infliximab. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2008;25(2):143–9.

Sweiss NJ, Barnathan ES, Lo K, Judson MA, Baughman R. C-reactive protein predicts response to infliximab in patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010;27(1):49–56.

Damsky W, Thakral D, Emeagwali N, Galan A, King B. Tofacitinib treatment and molecular analysis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2540–6.

Rotenberg C, Besnard V, Brillet PY, Giraudier S, Nunes H, Valeyre D. Dramatic response of refractory sarcoidosis under ruxolitinib in a patient with associated JAK2-mutated polycythemia. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(6).

Kono M, Kono M, Jodo S. A case of refractory acute sarcoid myopathy successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Scand J Rheumatol. 2018;47(2):168–9.

Linger MW, van Driel ML, Hollingworth SA. Off-label use of tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors and anakinra at an Australian tertiary hospital. Intern Med J. 2016;46(12):1386–91.

Shenoy N, Tesfaye M, Brown J, Simmons N, Weiss D, Meholli M, et al. Corticosteroid-resistant bulbar neurosarcoidosis responsive to intravenous immunoglobulin. Pract Neurol. 2015;15(4):289–92.

Awano N, Inomata M, Kondoh K, Satake K, Kamiya H, Moriya A, et al. Mixed-type multicentric Castleman’s disease developing during a 17-year follow-up of sarcoidosis. Intern Med. 2012;51(21):3061–6.

Semiz H, Kobak S. Coexistence of sarcoidosis and adult onset Still disease. Reumatol Clin. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2017.04.004 (epub 19 May 2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this review.

Conflict of interest

Christina Dai, Shawn Shih, Ahmed Ansari, and Young Kwak have no conflicts of interest to declare. Naveed Sami was a previous sub-investigator for Centocor clinical trial for sarcoidosis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, C., Shih, S., Ansari, A. et al. Biologic Therapy in the Treatment of Cutaneous Sarcoidosis: A Literature Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 20, 409–422 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-019-00428-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-019-00428-8