Abstract

Purpose of Review

The goals of the report are to integrate recent and key foundational gender- and sex-related, post-traumatic brain injury (TBI) literature across several research domains, to highlight need for increased cross-field communication using an integrative biopsychosocial research model, and to provide recommendations for further research approaches and foci.

Recent Findings

Recent findings of TBI studies addressing gender and/or biological sex provide evidence of women’s unique risks for injury, significant differences in severity, type, and number of post-TBI symptoms reported by women vs. men, and complex, interactive molecular, genetic, psychosocial, and physiological factors that contribute differently to TBI outcomes for the sexes.

Summary

Brain injury researchers, following years of failed clinical trials and mixed findings, are adopting new methods for more precisely characterizing differing effects of sex on both responses to TBI and recovery trajectories as well as underlying causes of these differences. New approaches include analysis of large data sets, use of sophisticated statistical models, more consistent exploration of sex-specific effects of TBI in more TBI study domains, and use of more precise measures. Increased cross-field communication and collaboration, stratification by sex, and increased adoption of these approaches are recommended to help advance understanding of TBI and move us closer to treatment development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) researcher Donald Stein recently reported disappointing statistics at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) in Atlanta, Georgia [1•]. After hundreds of TBI intervention trials, stated Stein, there is no evidence of efficacy for any treatment [1•, 2•]. The preclinical and human studies of sex hormones as neuroprotective for TBI and as potential keys to targeted treatments may be one of the best-known bodies of research related to gender and TBI [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, despite a decade of research of phase II trials suggesting that the sex hormones progesterone and estradiol were neuroprotective and might be key candidates for treatment development, two large phase III clinical trials of progesterone were stopped for futility [2•, 16•, 17•]. Similarly, the work of brain injury researchers looking at gender as a covariate in post-TBI psychosocial outcomes continues to yield mixed evidence of differences in survival, symptom profiles, and recovery trajectories [18,19,20, 21•, 22,23,24, 25•, 26,27,28,29,30]. Furthermore, findings of a post-TBI female recovery advantage are moderated by a range of sociocultural variables, sex-specific challenges, premorbid and comorbid issues, or sex-based developmental factors [31,32,33,34,35]. In the wake of clinical trial failures and inconsistent psychosocial study findings, Stein and other brain injury investigators are recommending reevaluation of models and methodology for improved approaches to studying biological sex and TBI [1•, 2•, 16•, 17•]. In the meantime, the multiple deficits common to TBI continue to significantly and negatively affect all domains of functioning and derail life promise and quality for thousands each year [36•].

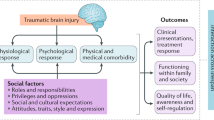

Very few disabling injuries and illnesses are as challenging as TBI is to researchers, survivors, family members and caregivers, clinicians, and healthcare systems [36•, 37•, 38]. The heterogeneity of TBI, with individual variability in level of severity, profile of deficits, and pace and degree of recovery, is a major reason for the challenges and is also a barrier to brain injury researchers’ progress toward treatment discovery [37•]. However, scientists studying and publishing about TBI within their own domains may not always cross talk or read about the work of TBI or concussion researchers in other domains. For example, investigators of injury due to sports concussion, military blasts, and civilian car crashes may need a more integrative view of the state of the science of gender/biological sex and TBI. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (WHO-ICF) domains of impairments in body function, activity limitations, and participation restrictions provide a comprehensive and integrative biopsychosocial rehabilitation model that could be a frame for integrating these domains of study [39•]. The WHO model supports multidimensional study of all factors potentially influencing the cause, physical and psychological response to, and outcome of sustaining disabling illness or injury. A few TBI researchers have incorporated the WHO or other integrative models in their work [40, 41, 42•]. Those that use this model, as Wagner outlines in a recent paper [40], can link biologic or molecular variables, such as sex hormones, with functional, behavioral, or biometric performance measures toward a more comprehensive understanding of impact of TBI on women and men. Use of such models can augment discovery, development, and application of findings in TBI rehabilitation.

There are two goals of this report. The first goal is to review and integrate a range of foundational and recent gender- and sex-related related post-TBI literature across several clinical domains biological sex and gender. The second goal is to highlight need for increased cross-field communication and provide recommendations for further research approaches and foci to advance understanding of gender, biological sex, and TBI.

Gender, Biological Sex, and TBI: Domains of Study

It is worth clarifying the terms “sex” and “gender,” at the outset of this report. Conflation of these terms is common in the brain injury and rehabilitation literature and reflects a lack of precision of language that may lead to confusion and distraction from research goals of increasing understanding of TBI [43]. The Institutes of Medicine (IOM) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) position on the term “sex” is that it describes biological and physical characteristics of the male and female bodies and includes anatomical, genetic, physiological, and hormonal characteristics in this construct [44]. In contrast, the term “gender” is a socio-culturally based construct that is fluid. Gender refers to what is socially termed “feminine” or “masculine” and how these qualities are manifested in life roles, self-identifications, and social relationships [43,44,45]. Gender also encompasses society expectations, behavioral norms, and labels applied to men and women [45]. In 2015, NIH announced that investigators were required to include consideration of sex as a biological variable in all aspects of proposed human and preclinical research projects [46••]. Perhaps in part due to this requirement, focus on gender and biological sex as covariates has increased in many TBI research domains over the past several years. A review of recent findings in several of these domains follows.

Exemplars of Military Publications with Focus on Sex and TBI

The US involvement in Middle Eastern conflicts and war theaters has led to increased research on effects of blast-, service-related, and other off-duty causes of TBI. Amoroso [47•], and Iverson et al. [48•] commented on the past disproportionate focus on men in TBI research enrolling post-deployment veterans. While they note that earlier study cohorts reflected the smaller numbers of women serving in combat theaters of US Middle Eastern war efforts, they report subsequent data showing large numbers of women veterans presenting with more severe and persistent TBI symptoms after deployment than male veterans. Iverson et al. [48•] examined administrative records for a large sample of veterans (12,605) who served in United States Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) combat theaters. Similar to civilian concussion reports, reviewed in the next section, their findings included significant sex differences with female veterans reporting more symptoms and more unique types of psychiatric disorders as well as symptoms of greater severity than their male counterparts. These findings were moderated by blast exposure and TBI. Compared to men in the Iverson et al. study, women veterans were less likely to be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 2 times more likely to have a diagnosis of depression, 1.3 times more likely to have a non-PTSD anxiety disorder, and, when diagnosed with PTSD, women were 1.5 times more likely to have comorbid depression. In addition, women in the Iverson study [48•] reported significantly more severe symptoms across many neurobehavioral domains. Two additional recent studies examining mTBI and symptom reporting in military service members or veterans [49•, 50] also found that, compared to active duty and veteran men, women service members and veterans with mTBI reported significantly higher numbers of post-injury symptoms including more severe physiological, somatosensory, vestibular, cognitive, psychological, and neurobehavioral symptoms. Amoroso et al. and Iverson et al. also discussed both pre-military and service-related exposure of women to intimate partner violence (IPV) and training or off-duty risks of head injury that are unique to women service members/veterans [47•, 48•]. Amoroso and Iverson [47•, 48•] both concluded that considering the increase in women service members and veterans in Middle Eastern or US locations, and their comparatively higher risk of TBI, providers of mental health and rehabilitation services need to continue to meet needs for assessment and intervention for these women.

Exemplars of Sports Medicine Publications with Focus on Sex and TBI

Sports medicine publications focus overarchingly on concussion due to a range of practice- and play-related injuries but have increasingly assessed sex differences in concussion-risk of sport, physiological risk factors for injury, symptoms, and recovery [51•]. For example, compared to men playing sports, Canadian female athletes are concussed more frequently in sport practice and play, especially in rugby and women’s hockey [51•]. In the United States (U.S.) women’s sports-related concussion rates are reported to be highest for ice hockey in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), followed by soccer and basketball. Male athletes are most often concussed during wrestling, ice hockey, and football [52••]. Sports medicine researchers are also reporting significant sex differences in cognitive domains of impairment after concussion, and in the common complexity of post-TBI neurobehavioral symptoms. For example, Sandel et al. [53•] found that female, as opposed to male, lacrosse and soccer players aged 13–17 reported more symptoms, scored more poorly on all cognitive tests, and took longer to recover after concussions than males. Sufrinko and colleagues [54•] found that women athletes had higher post-concussion syndrome (PCS) scores and poorer vestibular-ocular reflex scores than men. Zuckerman et al. [55•] noted that compared to concussed male athletes, women in sports have greater severity of sleep loss, a greater aggregate of symptoms, and take longer than men to return to baseline after concussion. Van der Horn et al. found that women more frequently developed depression after concussion [56]. Yilmaz and colleagues reported that women with concussion complain of post-traumatic headache, and continuation of this concussion symptom, more often than men [57••]. Also, youth sports concussion researchers report that girls are more likely to have more post-concussion symptoms [58•, 59•], sleep disturbances [58•], and more prolonged symptom duration [59•]. A recent review [60•] and additional study [61•] of sex differences in post-concussion effects found that the sexes do not differ in type of cognitive deficits reported after sport-related concussion. However, Oyegbile et al. [62•] noted that sleep disturbance mediated cognitive dysfunction in both men and women, and, as has been reported in other studies [58•], women are significantly more likely than men to experience post-concussion sleep disturbance. In sum, in comparison to men, the evidence supports that female athletes have unique risk for concussion, and for different and more intensive responses of longer duration men. These findings echo those of the recent military research by Amoroso and Iverson [47•, 48•] on mild TBI showing that, compared to men, active duty or veteran women are at greater risk for persistent, different, and more intense symptoms following mTBI, and for intimate partner violence resulting in concussions [47•, 48•]. Also, in an earlier paper, Barnes et al. [63] reported that women are more at risk than men for concussion in sports such as soccer due to their smaller size, greater ball-to-head size ratio than for men, and their comparatively weaker neck muscles. Further cross-field research into underlying complexities, associated biopsychosocial variables, and needed changes in treatment and preventive interventions for these unique differences is needed, perhaps involving the two study domains, military and sports concussion, reviewed above.

Exemplars of Studies of Sex Differences in Civilian and Non-sport-Related TBI

Mortality, Complications, and Survival

Several studies, spanning this last decade, are exemplars of the mixed findings on sex and mortality in acute and post-acute TBI populations. For example, Ponsford et al. [64] compared men and women admitted emergently for severe TBI on rates of survival. After controlling for GCS, age, and cause of injury, women participants survived at a significantly lower rate than men and also had poorer outcomes at 6 months post-injury. In a 2013 study using a very large sample of pubescent and prepubescent pediatric patients with TBI, Ley et al. [65] reported that pubescent girls were more likely to survive TBI than both prepubescent girls and pubescent boys and concluded that endogenous sex hormones might have neuroprotective effects after head injury for girls. In an additional example, Herrera-Molero and colleagues [66•] noted that, during early intensive care, women had higher rates of death than men after TBI, but mortality was mediated by their higher Apache Scores, greater rates of hypotension, and transfusions than males. Herrera-Molero et al. did not find any sex differences in functional status at 6-month follow-up. However, in an outpatient population, Brooks et al. [67, 68•] noted that reduced life expectancy is more likely for older men after severe TBI than for older women with TBI, especially when men have severe deficits, and were middle-aged to elderly at onset. Research findings are also mixed related to acute and post-acute complications. As reported by Herrera-Molero [66•], women have higher APACHE II scores than men with TBI as well as a higher incidence of pre-hospital hypotension, anemia, and transfusion than men after TBI. Overall, findings on post-TBI mortality and survival show that moderating variables of age, sex, timing and duration of measurement, complications, comorbid conditions, and degree of disability may partially explain the mixed results. Women with TBI may be more at risk early on in recovery due to complications in the ICU and other factors that are not yet fully explored. Post-TBI, older men seem to be more at risk for reduced life expectancy, especially if they have extensive disabilities.

Trajectories of Recovery—Access to and Progress in TBI Rehabilitation

While Graham et al. [24] found that women with TBI have shorter lengths of acute hospital and rehabilitation stay and more likelihood of receiving home health care after discharge than men with TBI, no sex-specific disparities in access to rehabilitation are currently being reported in the literature. The advent of sophisticated statistical models, such as latent class mixed models, have aided researchers in identifying predictors of outcomes related to biological sex/gender and TBI. For example, Howrey et al. [25•] applied latent class analysis to a large data set and found that younger men with TBI were more likely than injured women of matched age to have cognitive impairment and longer lengths of stay. Comorbidities and age are also more recently noted to affect recovery by Chan et al. [69•]. However, similar to studies on mortality and sex reviewed above, while sex by itself did not predict rehabilitation outcomes in Chan et al. study, sex-specific multivariable linear regression analyses identified factors differently associated with rehabilitation outcomes for both men and women [69•]. Women in Chan et al. study who were injured in car crashes had improved recovery due to increased insurance coverage whereas comorbidities were specifically and differently predictive of outcome for men.

Return to Work

Return to work is a post-acute benchmark for TBI recovery and is often a proxy for outcomes. Women have been and are still reported to be less likely to return to work than men after TBI [21•, 41, 70], and, if they return, there are variables that significantly moderate their work hours and how long it takes them to go back. These variables include marital status [70], whether the work environments as well as their home environments are perceived to be supportive [71, 72], and whether they are proactive in seeking work after injury [70, 71]. A recent qualitative study found that women were not only significantly more likely than men with TBI to be proactive in returning to work, but also more likely to stay in a work setting that they perceived as supportive [71].

Gender and Symptom Profiles After TBI: Cognition and Neurobehavioral Status

As noted in the section above on concussion and sex, symptom reporting is different for men and women after TBI. The brain injury literature reflects a long-standing interest in the cognitive and neurobehavioral changes and symptom profiles after TBI. Symptoms reported include common post-injury complaints of impaired recall, poor attention, and confusion [72,73,74]. Work in the post-TBI neurocognitive study domain has shown sex differences, but not in consistent or predicted directions [3, 73]. For example, Niemeier et al.’s [3] study hypothesis was that, based on Soules Reproductive Life Phases [3] and age groupings, presumed higher levels of endogenous sex hormones in younger men and women participants in a TBI Model Systems study would result in comparatively better performances on neuropsychological tests than men and women in older age groups. However, Niemeier et al. eldest female study participants with moderate to severe TBI had significantly better neuropsychological test scores in areas of memory and processing than the youngest women. Oldest women in the study also had significantly better mental flexibility and memory than the oldest men [3]. Ratcliff et al. [75] noted that female participants with moderate to severe TBI performed significantly better than men on tests of attention/working memory and language but that injured male participants outperformed women in visual analytic skills. Similarly, women with concussion in Suffrinko et al. [64] study of athletes were significantly more likely than men to exhibit ocular and vestibular problems. However, women with TBI have outperformed men in executive functions in both earlier and more recent studies of post-TBI neuropsychological status [28, 29, 42•]. Developmental cognitive literature findings also show long-standing sex differences in many of these same abilities for healthy men and women suggesting that TBI may accentuate these normative differences in ability [32, 33].

A recent movement toward development of an investigator/provider “common currency” of measurement of cognition resulted in use of item analysis and Rasch models for revising legacy cognitive tests toward more precisely measuring symptoms [76]. The resulting, much shorter, but reportedly more accurate National Institutes of Health (NIH) Toolbox set of tests now are available to characterize a range of TBI mental health and cognitive symptoms [76]. Publications describing the large-scale work being done on these new, more precise measures of cognition have somewhat supplanted papers reporting results of more lengthy neuropsychological test characterizations of post-TBI deficits. However, the norming process involved in the Toolbox development will likely aid additional study of sex differences in post-TBI cognitive and neurobehavioral deficits.

Variables associated with performance on tests of cognition include some sex-specific post-TBI problems that could affect performance on ability tests. For example, sex differences exist in post-TBI sleep disturbance, with women more likely to have problems with sleep onset and sleep maintenance [58•, 59•, 62•]. Poor sleep has a significant effect on cognition which may put women more at risk for cognitive deficits post-TBI. Women and men also experience and report pain differently after TBI after concussion [77•] and pain might cause disruptions of attention and memory.

Diagnostics and Prognostics; Molecular Level Studies of Sex and TBI

Following cessation of the progesterone phase III trials for futility [1•, 2•] and the U.S. Obama administration initiated “Brain’ Initiative [78], which was reflected in funding announcements for more basic science research to explore the neurologic and molecular complexities underlying both TBI response and recovery. In addition to endocrine factors affected by and in response to a TBI, subsequent research foci have included a range of studies of serum and cerebral spinal fluid, genomics, and inflammatory markers for evidence of biomarkers. Both animal and human studies are focusing on subject characteristics and injury responses to increase understanding of this injury and gain keys to treatment. Human studies are exploring apparent injury-related suppression of sex and stress hormones, relative risk of higher serum levels of sex hormones for post-TBI mortality, related variables such as menstrual phase and use of oral contraceptives at time of injury, subsequent impact on reproductive and other body processes, and how these affect long-term outcomes after TBI [79, 80••, 81•, 82•, 83•, 84•, 85•]. Animal model investigators are observing significant sex-dependent alterations in the HPA axis after blast mTBI [86], more widespread effects of mTBI for female rats [87•], more sex-specific changes in the social brain network causing social dysfunction (females over males) [88], and increased depressive-like behavior in female rats with repeated mTBI [89•]. Much more research is needed to parse out the intricate interaction TBI effects, injured individuals’ physiological and psychological responses to injury and treatment, and their possible impact on recovery trajectories for both men and women.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our reported findings suggest that the study of sex and TBI is evolving. We know much more about sex-specific effects of TBI, largely as a result of the increase in sports and military concussion and mild TBI studies that have stratified for sex. More sophisticated statistical models and big data studies have helped investigators study both individual variability and covariates such as biological sex or gender after TBI. Molecular level studies are also delving more deeply into neurologic, inflammatory, and hormonal responses to TBI. While much more research is needed, potential candidate markers of severity and progress in recovery and their psychosocial and cognitive correlates have increased from these investigations. Sports concussion and military studies of mTBI are increasingly documenting sex differences in symptom profiles, possible hormonal effects on injury response recovery trajectories, throughout the TBI severity continuum.

In the wake of mixed findings and failed trials of treatments, investigators are also reconsidering issues with methodology and scientific rigor in trials that may have contributed to efforts toward trials of treatments that failed that and ultimately produced inconsistent or no evidence for treatments [1•, 2•]. Current integrative and collaborative interest through data sharing is occurring between military and civilian rehabilitation clinical and professional and research organizations such as FITBIR, TBI Interagency Conferences, and TBI Model Systems Polytrauma Centers [90•, 91, 92]. In addition, investigators are more carefully planning enrollment cohorts through deciding on study inclusion and exclusion criteria to improve study validity and rigor. Researchers are also more carefully considering potential confounds or moderating variables [1•, 2•]. Age, level of severity of disability, education, and amount of rehabilitation received join other variables having more to do with socially and environmentally determined gender differences in access to services after TBI, or differential recovery expectations for men and women [31, 34, 35].

The past 5 years of TBI literature shows increased attention to sex and gender. The results including exciting new information about sex differences in risk for, symptom profiles, recovery duration after especially mild TBI/concussion in civilian and military service member or veteran adults, as well as in adolescents, and children. At the same time, investigators are still not consistently considering sex and gender in their research design, methodology, analyses, or reporting of outcomes. There is an ongoing need to consistently integrate sex and gender in to concussion, military TBI, and civilian TBI research. In addition, complex designs with a range of statistical techniques may uncover interesting sex-specific predictors of outcomes after TBIs, even if the broad analyses have not found sex itself to be a determinant of outcomes after TBI. These efforts will help guide more rigorous future investigations that can inform more sex- and gender-related clinical guidelines and possibly treatment development for this devastating injury.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

• Stein DG. What have we learned about treating brain injuries from the repeated failures of clinical trials. Featured Session, American Congress of Rehabilitation Annual Conference, October 28, 2017, Atlanta, GA. This paper provides an overview of Phase II and III TBI treatment trials and focuses on need to reevaluate and change methods in this gender and TBI study domain.

• Stein DG. Embracing failure; What the Phase III progesterone studies can teach about TBI clinical trials. Brain Inj. 2015;29(11):1259–72 This reference asks investigators to consider reasons for failed clinical trials and need to for new approaches to gender/TBI research.

Niemeier JP, Marwitz JH, Walker WC, Davis LC, Bushnik T, Ripley DL, et al. Are there cognitive and neurobehavioural correlates of hormonal neuroprotection for women after TBI? Nuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23(3):363–82.

Davis DP, Douglas DJ, Smith W, Sise MJ, Vilke GM, Holbrook TL, et al. Traumatic brain injury outcomes in pre-and post-menopausal females versus age-matched males. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:140–8.

Yeung JH, Mikocka-Walus AA, Cameron PA, Poon WS, Ho HF, Chang A, et al. Protection from traumatic brain injury in hormonally active women vs. men of a similar age: a retrospective international study. Arch Surg. 2011;146:436–42.

Stein DG. Brain damage, sex hormones and recovery: a new role for progesterone and estrogen? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:386–91.

Stein DG, Wright DW. Progesterone in the clinical treatment of acute traumatic brain injury. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:847–57.

Stein DG, Wright DW, Kellermann AL. Does progesterone have neuroprotective properties? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:164–72.

Wagner AK, Willard LA, Kline AE, Wenger MK, Bolinger BD, Ren D, et al. Evaluation of estrous cycle stage and gender on behavioral outcome after experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 1998;2004:113–21.

Pettus EH, Wright DW, Stein DG, Hoffman SW. Progesterone treatment inhibits the inflammatory agents that accompany traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2005;1049:112–9.

Gibson CL, Gray IJ, Bath PM, Murphy SP. Progesterone for the treatment of experimental brain injury: a systematic review. Brain. 2008;131:318–28.

Kokiko ON, Murashov AK, Hoane MR. Administration of raloxifene reduces sensorimotor and working memory deficits following traumatic brain injury. Behav Brain Res. 2006;170:233–40.

Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, Clark PL, Frankel M, Goldstein FC, et al. Pro-TECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:391–402 402e1-2.

Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu. Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2009;12:R61.

Stein DG. A clinical/translational perspective: can a developmental hormone play a role in the treatment of traumatic brain injury? Horm Behav. 2013;63:291–300.

• Skolnick BE, Maas AI, Narayan RK, van der Hoop RG, MacAllister T, Ward JD, et al. SYNAPSE: Trial Investigators A clinical trial of progesterone for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2467–76 This paper describes results of a trial of progesterone for persons with severe TBI and the lack of evidence of efficacy.

• Wright DW, Yeatts SD, Silbergleit R, Palesch YY, Hertzberg VS, Frankel M, et al. Very early administration of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2457–66 The results of a failed trial of progesterone for acute TBI are described.

Berry C, Ley EJ, Tillou A, Cryer G, Margulies DR, Salim A. The effect of gender on patients with moderate to severe head injuries. J Trauma. 2009;67:950–3.

Leitgeb J, Mauritz W, Brazinova A, Janciak I, Majdan M, Wilbacher I, et al. Effects of gender on outcomes after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2011;71:1620–6.

Bounds TA, Schopp L, Johnstone B, Under C, Goldman H. Gender differences in a sample of vocational rehabilitation clients with TBI. NeuroRehabil. 2003;18:189–96.

• Cuthbert JP, Pretz CR, Bushnik T, Fraser RT, Hart T, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, et al. Ten-year employment patterns of working age individuals after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:2128–36 This work provides large data set analyses and findings related to outcomes after TBI showing sex differences.

Farace E, Alves WM. Do women fare worse? A metanalysis of gender differences in outcome after traumatic brain injury. Neursurg Foc. 2000;8:e6.

Goranson TE, Graves RE, Allison D, Freniere RL. Community integration following multidisciplinary rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2003;17:759–74.

Graham JE, Radice-Neumann DM, Reistetter TA, Hammond FM, Dijkers M, Granger CV. Influence of sex and age on inpatient rehabilitation outcomes among older adults with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:43–50.

• Howrey BT, Graham JE, Pappadis MR, Granger CV, Ottenbacher KJ. Trajectories of functional change after inpatient rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1606–13 The paper reports findings showing sex and gender differences in recovery.

Liossi C, Wood R. Gender as a moderator of cognitive and affective outcome after traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2009;21:43–51.

Moore DW, Ashman TA, Cantor JB, Krinick RJ, Spielman LA. Does gender influence cognitive outcome after traumatic brain injury? Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010;20:340–54.

Niemeier JP, Marwitz JH, Lesher K, Walker WC, Bushnik T. Gender differences in executive functions following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2007;17:293–313.

Niemeier JP, Perrin PB, Holcomb MG, Rolston CD, Artman LK, Lu J, et al. Gender differences in awareness and outcomes during acute traumatic brain injury recovery. J Women's Health. 2014;23:573–80.

Ponsford JL, Myles PS, Cooper DJ, Medermott FT, Murray LJ, Laidlaw J, et al. Gender differences in outcome in patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2008;39:67–76.

Drapeau A, Boyer R, Lesage A. The influence of social anchorage on the gender differences in the use of mental health service. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36:372–84.

Munro CA, Winicki JM, Schretlen DF, Gower EW, Turano KA, Munoz B, et al. Sex differences in cognition in healthy elderly individuals. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging. 2012;19:739–68.

Murre JM, Janssen SM, Rouw R, Meeter M. The rise and fall of immediate and delayed memory for verbal and visuospatial information from late childhood to late adulthood. Acta Psychol. 2013;142:96–107.

Redpath S, Williams W, Hanna D, Linden M, Yates P, Harris A. Healthcare professionals; attitudes towards traumatic brain injury (TBI): the influence of profession, experience, etiology and blame on prejudice towards survivors of brain injury. Brain Inj. 2010;24:802–11.

Engel de Abreu PM, Puglisi JL, Crus-Santos A, Befi-Lopes DM, Martin R. Effects of impoverished environmental conditions on working memory performance. Memory. 2014;22:323–31.

• Flanagan SR. Invited commentary on ‘Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Report to Congress: Traumatic brain injury in the United Stated: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation.’. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1753–5 This paper summarizes the conclusions of a Congressional committee of experts that showed critical continued need to find treatments and address gaps in care for people with TBI and their families.

• Davanzo JR, Sieg EP, Timmons SD. Management of traumatic brain injury. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:1237–53 This work provides an overview of heterogeneity of TBI and barriers to finding treatments.

Saban KL, Hogan NS, Hogan TP, Pape TL. He looks normal but…challenges of family caregivers of veterans diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40:277–85.

• Wade DR, Halligan PW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:995–1004 This editorial covers the need to apply the biopsychosocial model to healthcare management to improve outcomes.

Wagner AK. TBI Rehabilomics research: An Exemplar of a biomarker-based approach to precision care for populations with disability. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17:84.

Xiong C, Martin T, Sravanapudi M, Colantonio A, Mollayeva T. Factors associated with return to work in men and women with work-related traumatic brain injury. Disabil Health J. 2016;9:439–48.

• Richardson C, McKay A, Ponsford JL. The trajectory of awareness across the first year after traumatic brain injury; the role of biopsychosocial factors. Brain Inj. 2014;28:1711–20 This study illustrates the value of applying a biopsychosocial model to understand brain injury complexities and for identification of gender and biological sex differences that could impact treatment.

Colantonio A. Sex, gender, and traumatic brain injury: a commentary. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:51–4.

National Institute of Women’s Health, National Institutes of Health. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender/ retrieved October 30, 2018.

Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting sex, gender, or both in clinical research? JAMA. 2016;316:1863–4.

•• National Institutes of Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19934/ retrieved October 21 2018. This is the announcement of NIH guidance on investigator and grant applicant attention to sex as a biological variable in research.

• Amoroso T, Iverson KM. Acknowledging the risk for traumatic brain injury in women Veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:318–23 This paper brings attention to epidemiology of TBI and women veterans as well as describes unique risks for TBI and challenges of women Veterans with TBI.

• Iverson KM, Sayer NA, Meterko M, Stolzmann K, Suri P, Gormley K, et al. Intimate partner violence among female OEF/OIF/OND veterans who were evaluated for traumatic brain injury in the Veterans Health Administration: A preliminary investigation. J Interpers Violence. 2017;1:8862605. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626051770491This article importantly draws attention to unique risks for women veterans for sustaining a TBI from intimate partner violence.

• Lippa SM, Brickell TA, Bailie JM, French LM, Kennedy JE, Lange RT. Postconcussion symptom reporting after mild traumatic brain injury in female service members: Impact of gender, posttraumatic stress disorder, severity of injury, and associated bodily injuries. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:101–12 The paper shows differential effects of sex on concussion/mTBI for service members.

Brickell TA, Lippa SM, French LM, Kennedy JE, Bailie JM, Lange RT. Female service members and symptom reporting after combat and non-combat-related mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:300–12.

• Black AM, Sergio LE, Macpherson AK. The epidemiology of concussions: Number and nature of concussions and time to recovery among female and male Canadian varsity athletes 2008 to 2011. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;27:52–6 This paper reports higher frequency of concussions and association with sport played for Canadian women compared to Canadian men athletes.

•• Zuckerman SL, Kerr ZY, Yengo-Kahn A, Wasserman E, Covassin T, Solomon GS, et al. Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in NCAA athletes from 2009–2010 to 2013–2014: incidence, recurrence, and mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:NP5 This work identifies U.S. sex differences in rate of concussion as well as sports activities most likely to result in concussion.

• Sandel K, Schatz P, Goldberg KB, Lazar M. Sex-based differences in cognitive deficits and symptom reporting among acutely concussed adolescent lacrosse and soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:937–44 This paper identifies sex differences in post-concussion deficits and symptoms for U.S. athletes.

• Sufrinko AM, Mucha A, Covassin T, Marchetti G, Elbin RJ, Collins MW, et al. Sex differences in vestibular/ocular and neurocognitive outcomes after sport-related concussion. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;27:190–4 Sex differences are reported in cognitive/neurocognitive outcomes after concussion.

• Zuckerman SL, Apple RP, Odom MJ, Lee YM, Solomon GS, Sills AK. Effect of sex on symptoms and return to baseline in sport-related concussion. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13:72–81 The work reports sex-dependent symptoms and recovery trajectories for sports-related concussions.

van der Horm HJ, Spikman JM, Jacobs B, van der Naalt J. Postconcussive complaints, anxiety, and depression with vocational outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) of various severities and to assess sex differences. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:867–74.

•• Yilmaz T, Roks G, de Koning M, Scheenen M, van der Horn H, Plas G, et al. Risk factors and outcomes associated with post-traumatic headache after mild traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med J. 2017;34:800–5 The study found that women are more likely to have headache after mTBI.

• Gauvin-Lepage J, Friedman D, Grilli L, Gagnon I. Effect of sex on recovery from persistent postconcussion symptoms in children and adolescents participating in an active rehabilitation intervention. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018. https://doi.org/10.10897/HTR.0000000000000402The paper discusses findings that girls in concussion recovery have more symptoms, longer, than boys.

• Thomas DJ, Coxe K, Li H, Pommering TL, Young JA, Smith GA, et al. Length of recovery from sports-related concussions in pediatric patients treated at concussion clinics. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28:56–63 This recent publication report recovery lengths are longer for women athletes after concussion.

• Lin CY, Casey E, Herman DC, Katz N, Tenforde AS. Sex differences in common sports injuries. PMR. 2018;10:1073–82 The paper states that more women athletes have concussions.

• Brooks BL, Silverberg N, Maxwell B, Mannix R, Zafonte R, Berkner PD, et al. Investigating effects of sex differences and prior concussions on symptom reporting and cognition among adolescent soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:961–8 The authors report that women soccer players have different and longer lasting symptoms than men.

• Oyegbile TO, Delasobera BE, Zecavati N. Gender differences in sleep symptoms after repeat concussions. Sleep Med. 2017;40:110–5 This paper reports sex-specific differences in post-concussion symptoms in 8 to 17-year-old athletes showing girls have worse and long-lasting sleep difficulties than men after concussion.

Barnes BC, Cooper L, Kirkendall DT, McDermott TP, Jordan BD, Garrett WE. Concussion history in elite male and female soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:433–8.

Ponsford JL, Myles PS, Cooper DJ, Mcdermott FT, Murray LJ, Laidlaw J, et al. Gender differences in outcome in patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury. Injury. 2008;39:67–76.

Ley EJ, Short SS, Liou DZ, Singer MB, Mirocha J, Melo N, et al. Gender impacts mortality after traumatic brain injury in teenagers. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:682–6.

• Herrera-Melero MC, Egea-Guerrero JJL, Vilches-Arenas A, Rincon-Ferrari MD, Flores-Cordero JM, Leon-Carrion J, et al. Acute predictors for mortality after severe TBI in Spain: Gender differences and clinical data. Brain Inj. 2015;29:1439–44 The study showed that women have greater risk of mortality early on in recovery due to complications than men do after severe TBI.

Brooks JC, Strauss DJ, Shavelle RM, Paculdo DR, Hammond FM, Harrison-Felix CL. Long-term disability and survival in traumatic brain injury: results from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research model systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:2203–9.

• Brooks JC, Shavelle RM, Strauss DJ, Hammond FM, Harrison-Felix CL. Long-term survival after traumatic brain injury Part II: Life expectancy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1000–5 The paper reports sex differences in life expectancy after TBI.

• Chan Y, Mollayeva T, Ottenbacher KJ, Colantonio A. Clinical profile and comorbidity of traumatic brain injury among younger and older men and women: a brief research note. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:371 The study found that women and men have differing comorbidities that impact recovery.

Corrigan JD, Lineberry LA, Komaroff E, Langlois JA, Selassie AW, Wood KD. Employment after traumatic brain injury: differences between men and women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1400–9.

Stergiou-Kita M, Mansfield E, Sokoloff S, Colantonio A. Gender influences on return to work after mild traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:S40–5.

Arciniegas D, Adler L, Topkoff J, Cawthra E, Filley CM, Reite M. Attention and memory dysfunction after traumatic brain injury: cholinergic mechanisms, sensory gating, and a hypothesis for further investigation. Brain Inj. 1999;13:1–13.

Donders J, Hoffman NM. Gender differences in learning and memory after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol. 2002;16:491–9.

Russell KC, Arenth PM, Scanlon JM, Kessler L, Ricker JH. Hemispheric and executive influences on low-level language processing after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2012;26:984–95.

Ratcliff JJ, Greenspan AL, Goldstein FC, Stringer AY, Bushnik T, Hammond FM, et al. Gender and traumatic brain injury: Dr. the sexes fare differently? Brain Inj. 2007;21:1023–30.

Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelaxo PD, Slotkin J, et al. The cognition battery of the NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function: validation in an adult sample. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20:567–78.

• Mollayeva T, Cassidy JD, Shapiro CM, Mollayeva S, Colantonio A. Concussion/mild traumatic brain injury related to chronic pain in males and females: A diagnostic modelling study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e5917 The study analyses revealed sex-specific differences in how men and women experience pain after TBI.

Weiss PS. President Obama announces the BRAIN initiative. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2873–4.

Wagner AK, McCullough EH, Nivonkuru C, Ozawa H, Loucks TL, Dobos JA, et al. Acute serum hormone levels: characterization and prognosis after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:871–88.

•• Wunderle K, Hoeger KM, Wasserman E, Bazarian JJ. Menstrual phase as predictor of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury in women. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29:e1–8 The paper reports effects of endogenous sex hormones and oral contraceptives on response to TBI.

• Ranganathan P, Kumar RG, Davis K, McCullough EH, Berga SL, Wagner AK. Longitudinal sex and stress hormone profiles among reproductive age and post-menopausal women after severe TBI: A case series analysis. Brain Inj. 2016;30:452–61 This paper looks at complexities of sex hormones and TBI. This paper looks at complexities of sex hormones and TBI.

• Santarsieri M, Niyonkuru C, McCullough EH, Dobos JA, Dixon CE, Berga SL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cortisol and progesterone profiles and outcomes prognostication after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:699–712 The study finds associations between stress and sex hormone CSF levels and outcomes after severe TBI.

• Juengst SB, Arenth PM, Wagner A. Inflammation and apathy associations in the first year after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:e98–9 This work links inflammation due to TBI with apathy during the first post-injury year.

• Juengst SB, Kumar RG, Failla MD, Goyal A, Wagner A. Acute inflammatory biomarker profiles predict depression risk following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:207–18 This work links inflammatory biomarkers of TBI with post-injury depression risk.

• Gallagher V, Kramer N, Abbott K, Alexander J, Breiter H, Herrold A, et al. The effects of sex differences and hormonal contraception on outcomes after collegiate sports-related concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:1242–7 Another paper (Wunderle) that similarly finds an association between outcomes and sex hormones/contraceptive use after concussion.

Russell AL, Richardson MR, Bauman BM, Hernandez IM, Saperstein S, Handa RJ, et al. Differential response of the HPA Axis to mild blast traumatic brain injury in male and female rats. Endocrinology. 2018;159:2363–75.

• Wirth P, Yu VV, Kimball AL, Liao J, Berkner P, Glenn MJ. New method to induce mild traumatic brain injury in rodents produces differential outcomes in female and male Sprague Dawley rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2017;290:133–44 Animal research study showing sex differences in outcomes from mTBI.

Semple BD, Dixit S, Shultz SR, Boon WC, O’Brien TJ. Sex-dependent changes in neuronal morphology and psychosocial behaviors after pediatric brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017;319:48–62.

• Wright DK, O’Brien TJ, Shultz SR, Mychasiuk R. Sex matters: repetitive mild traumatic brain injury in adolescent rats. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4:640–65 Recent study showing sex differences in effects of repetitive mTBI.

• Thompson HJ, Vavilala MS, Rivara FP. Chapter 1 Common Data Elements and Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System for TBI Research. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2015;33:1–11 The FITBUR informatics system is described.

Lamberty GJ, Nakase-Richardson R, Farrell-Carnahan L, McGarity S, Bidelspach D, Harrison-Felix C, et al. Development of a traumatic brain injury model system within the Department of Veterans Affairs Polytrauma System of care. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29:E1–7.

Traumatic Brain Injury Interagency Conference. https://interagencyconferencetbi.org/about/ Retrieved December 31, 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Janet Niemeier declares no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Brain Injury Medicine and Rehabilitation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niemeier, J.P. Biological Sex/Gender and Biopsychosocial Determinants of Traumatic Brain Injury Recovery Trajectories. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 7, 297–304 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-019-00238-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-019-00238-3