Abstract

Polyarteritis nodosa, which is a systemic vasculitis of small- and medium-sized arteries, can cause arterial aneurysms in various organs, sometimes resulting in aneurysm rupture and hemorrhage. A kidney is one of the major targets of polyarteritis nodosa. Here, we report a 73-year-old woman who presented with sudden-onset high fever, diarrhea, and renal injury with bilateral renal subcapsular hematoma shown on contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan. She did not have trauma and significant medical history other than breast cancer in remission. Serological and immunological tests except for anti-Sjögren's syndrome-A and anti-Sjögren's syndrome-B were all negative. Digital subtraction angiography revealed bilateral intrarenal micro aneurysms, which allowed us to diagnose the patient with polyarteritis nodosa. As continuous monitoring of bilateral intrarenal hematoma by ultrasonography and computed tomography scan did not detect progression of intrarenal hemorrhage and extra renal hematoma, transcatheter arterial embolization and nephrectomy were not performed. Although hemodialysis therapy was required temporarily for acute kidney injury with anuria, her general condition and kidney function remarkably improved after receiving systemic immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. In conclusion, this is a rare case of polyarteritis nodosa manifesting as spontaneous bilateral subcapsular renal hemorrhage with deteriorated renal function, which was successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Spontaneous sub capsular renal hematoma is a relatively rare disease caused by tumors, trauma, infection, vasculitis, and anticoagulant therapy. Only 3% of patients with this condition develop a bilateral hematoma. Additionally, the bilateral renal hematoma is commonly caused by polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). The distinct feature of PAN is necrotizing vasculitis with nodules in small- and medium-sized arteries, which can spread throughout the whole body. A kidney is one of the target organs in PAN, and kidney involvement is observed in more than 70% of patients with PAN [1, 2]. The main symptoms of PAN with kidney involvement are hematuria, proteinuria, and kidney failure. However, kidney hemorrhage from ruptured aneurysms is rare in PAN. Therefore, the mortality rate, renal prognosis, and appropriate treatments are not fully elucidated.

Herein, we report a case of bilateral kidney hematoma caused by PAN that was successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old female patient, without trauma and significant medical history other than breast cancer in remission, suddenly presented with high fever, diarrhea, and stomach pain. A local doctor observed severe kidney failure, inflammation, and bilateral subcapsular kidney hemorrhage on computed tomography (CT) scan. She was admitted to our hospital for further treatment and examination.

Upon admission, she had no symptoms related to large-vessel vasculitis (i.e., Takayasu's disease), such as carotidynia, decreased vision, claudication, dizziness, and headaches. Her vital signs, including temperature, were within normal range. However, blood pressure of 122/70 mm Hg on admission was strikingly increased from the 2nd day (200/160 mm Hg). Complete blood cell count and biochemical test results showed moderate leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 14,500/μL), mild anemia (hemoglobin level: 10.6 g/dL), renal failure (blood urea nitrogen [BUN] level: 52.1 mg/dL, creatinine [Cr] level: 5.48 mg/dL), and a high D-dimer level (9.81 μg/dL) (Table 1). The serum cholesterol levels (HDL-cholesterol 10 mg/dL, LDL-cholesterol 27 mg/dL) were not increased. On a urinalysis, the sediment contained 30–49 red blood cells (RBCs)/high-power field. The urinary protein excretion was 7.84 g/gCr. The fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) was 2.4%.

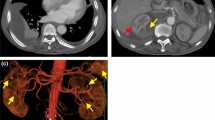

The serological tests for rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative except for anti-Sjögren’s syndrome (SS)-A and SS-B antibodies (Table 1). Moreover, all viral tests, including hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody, were negative. A contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed bilateral sub capsular kidney hemorrhage (right: 10.8 × 10.0 × 18.0 cm; left: 14.4 × 13.3 × 15.0 cm) without urinary tract obstruction, tumors, and cysts (Fig. 1). The bilateral intrarenal hematoma size was monitored via ultrasonography and CT scan regularly.

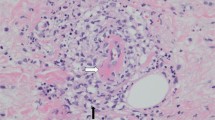

After admission, the patient received temporary hemodialysis therapy from days 2 to 4 due to anuria. Then, the patient’s renal function and urine volume gradually improved with supportive therapy. As intrarenal hemorrhage did not progress, and the extra renal hematoma was not detected, trans catheter arterial embolization (TAE) and nephrectomy were not performed. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered due to the presence of Escherichia coli in blood and urine cultures. However, antibiotic treatment was not significantly effective against inflammation. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the renal artery revealed minor aneurysms in the arcuate artery of both renal arteries (Fig. 2). No arterial aneurysm was found in other organs. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with PAN, which met the diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan, and the French Vasculitis Study Group. (Supplemental Tables 1–3) [3,4,5]. Then, she initially received steroid pulse therapy for 3 days (methylprednisolone [$RPSL] 1000 mg daily). Next, PSL 48 mg (0.8 mg × body weight [kg]) was administered. This therapy significantly decreased serum C-reactive protein level, which did not improve by the antibiotics (Fig. 3). In addition, intravenous therapy with cyclophosphamide (600 mg per day) was started on the 32nd day after admission. The patient’s kidney function (Cr level: 0.56 mg/dL, BUN level: 15.7 mg/dL) completely recovered, and she was discharged in good general condition on the 88th day after admission.

Discussion and conclusions

Herein, we report a 73-year-old female who developed bilateral renal sub capsular hematoma with anuric renal failure. The patient was diagnosed with PAN and responded well to immunosuppressive treatments.

To the best of our knowledge, 8 of 13 bilateral renal hemorrhage cases were caused by PAN based on previous studies in the English literature. The other causes of bilateral renal hemorrhage were trauma, infection, anticoagulant therapy, polycystic ovarian syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy [1, 2, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Bilateral renal hemorrhage in PAN has no distinct symptoms. Furthermore, obtaining histological findings via kidney biopsy is occasionally challenging. Hence, the diagnosis is likely to be complicated and delayed. In this case, the symptoms were fever and sudden stomach pain, which were not specific for PAN. Due to the high risk of hemorrhage, we performed DSA instead of kidney biopsy, which supported our diagnosis and treatment strategy. DSA is a useful option even for patients with a high risk of hemorrhage [5, 17].

The standard treatment for PAN is immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. Meanwhile, plasma exchange is performed as an alternative option therapy for PAN correlated with hepatitis B virus [17,18,19]. In previous cases of renal hemorrhage caused by PAN, the treatment used was immunosuppressive therapy [8,9,10]. However, the mortality rate among these patients was 50%, which was primarily caused by uncontrolled hemorrhage [8,9,10]. Thus, the control of widespread hemorrhage may be a key factor for survival. TAE and nephrectomy are considered to manage bleeding. In our case, these surgical approaches were not performed because of subcapsular hematoma, which was not extra renal, and the absence of active arterial extravasation on DSA. Monitoring of hemorrhage and changes in hematoma and blood tests could support our treatment decision on TAE or nephrectomy. The etiology of bilateral renal hematomas caused by PAN is not fully elucidated due to limited information. In the current case, the effect of other diseases, including Sjögren’s syndrome, could not be excluded. Thus, more cases should be assessed to investigate factors associated with ruptured aneurysms. In terms of renal replacement therapy, three of nine patients, including ours, required dialysis therapy. But, interestingly, all of them could terminate temporal dialysis therapy [11, 13]. While the pathogenesis of rapid renal dysfunction, in this case, is not clear, one may speculate that an external renal parenchyma and vessels compression by hematoma and hyperreninemia due to a decrease in renal blood flow might have played a role. In the clinical course, severe hypertension (200/160 mm Hg) and severe kidney failure (Fig. 2) were gradually attenuated, and finally, hemodialysis treatment was not required. Furthermore, a large amount of proteinuria without high cholesterol found on the admission was completely diminished on the seventh day after the admission, suggesting that a high physical pressure caused by bilateral hemorrhage in the renal parenchyma and vessels might have decreased [20,21,22].

In conclusion, we presented a rare case of PAN causing bilateral renal sub capsular hematoma with acute kidney injury. In addition to temporary hemodialysis therapy, the standard immunosuppressive therapy could remarkably improve a patient’s general condition and kidney function.

Abbreviations

- PAN:

-

Polyarteritis nodosa

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- FENa:

-

Fraction excretion of sodium

- TAE:

-

Trans catheter arterial embolization

- DSA:

-

Digital subtraction angiography

- PSL:

-

Prednisolone

- ADPKD:

-

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

References

Agarwal A, Bansal M, Pandey R, Swaminathan S. Bilateral sub capsular and perinephric hemorrhage as the initial presentation of polyarteritis nodosa. Internal Med Jpn Soc. 2012;51:1073–6.

Choi H-II, Kim YG, Kim SY, Jeong DW, Kim KP, Jeong KH, et al. Bilateral spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage due to initial presentation of polyarteritis nodosa. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:428074.

Lightfoot RW, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Zvaifler NJ, Mcshane DJ, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheumat. 1990;33:1088–93.

Guideline for management of vasculitis syndrome (JCS, 2008). Japanese Circulation Society. Circ J. 2011;75:474–503.

Henegar C, Pagnoux C, Puéchal X, Zucker JD, Bar-Hen A, le Guern V, et al. A paradigm of diagnostic criteria for polyarteritis nodosa: analysis of a series of 949 patients with vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1528–38.

Ruiz H, Saltzman B. Aspirin-induced bilateral renal hemorrhage after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy therapy: implications and conclusions. J Urol. 1990;143:791–2.

Gültekin N, Akin F, Küçükateş E. Warfarin-induced bilateral renal hematoma causing acute renal failure. Turk Kardiyol Dernegi Arsivi. 2011;39:228–30.

Unverdi S, Altay M, Duranay M, Kırbas I, Demirci S, Yuksel E. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting with splenic infarction, bilateral renal infarction, and hematoma. South Med. 2009;102:972–3.

Vo H, Showkat A, Chikkalingaiah KM, Nguyen C, Wall BM. Spontaneous massive bilateral peri-renal hemorrhage as a complication of ANCA-negative granulomatous vasculitis. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83:249–52.

Melamed N, Molad Y. Spontaneous retroperitoneal bleeding from renal microaneurysms and pancreatic pseudocyst in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:481–4.

el Madhoun I, Warnock NG, Roy A, Jones CH. Bilateral renal hemorrhage due to polyarteritis nodosa wrongly attributed to blunt trauma. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:563–7.

Presti JC, Carroll PR. Bilateral spontaneous renal hemorrhage due to polyarteritis nodosa. Western J Med. 1991;155:527–8.

Georgiou C, Krokidis M, Elworthy N, Dimopoulos S. Spontaneous bilateral renal aneurysm rupture secondary to polyarteritis nodosa in a patient with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia: a case report study. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:61–4.

Ullah A, Marwat A, Suresh K, Khalil A, Waseem S. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma: a rare presentation of polyarteritis nodosa. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2019;7:2324709619858120.

Sagcan A, Tunc E, Keser G, Bayraktar F, Aksu K, Memis A, et al. Spontaneous bilateral perirenal hematoma as a complication of polyarteritis nodosa in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2002;21:239–42.

Hirohama D, Miyakawa H. Bilateral spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage in an acquired cystic kidney disease hemodialysis patient. Case Rep Nephrol. 2012;2012:178426.

Mnif N, Chaker M, Oueslati S, Ellouze T, Tenzakhti F, Turki S, et al. Abdominal polyarteritis nodosa: angiographic features. J Radiol. 2004;85:635–8.

Guillevin L, Lhote F, Cohen P, Jarrousse B, Lortholary O, Généreau T, et al. Corticosteroids plus pulse cyclophosphamide and plasma exchanges versus corticosteroids plus pulse cyclophosphamide alone in the treatment of polyarteritis nodosa and churg-strauss syndrome patients with factors predicting poor prognosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1638–45.

Guillevin L, Lhote F. Treatment of polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome: indications of plasma exchanges. Transfus Sci. 1994;15:371–88.

Dopson SJ, Jayakumar S, Carlos J, Velez Q. Page kidney as a rare cause of hypertension: case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:334–9.

Teruya H, Yano H, Miyasato H, Kinjo M. Page kidney after a renal biopsy. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87:271–2.

Naranjo J, Villanego F, Cazorla JM, León C, Ledo MJ, García A, et al. Acute renal failure in kidney transplantation due to subcapsular hematoma after a renal allograft biopsy: report of two cases and literature review. Transplant Proc. 2020;52:530–33.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK reviewed the patient’s clinical data. YK and KI wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. YK, KI, YY, MA, YW, RY, and HH treated the patient, contributed to writing the manuscript, and revised the final version of the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Kambayashi, Y., Iseri, K., Yamamoto, Y. et al. Bilateral renal subcapsular hematoma caused by polyarteritis nodosa: a case report. CEN Case Rep 11, 399–403 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13730-022-00691-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13730-022-00691-5