Abstract

Purpose of Review

The aims of this narrative review were to (1) synthesise the literature on the relationship between screen time and important mental health outcomes and (2) examine the underpinning factors that can influence this association.

Recent Findings

Paralleling the rise of mental health issues in children and adolescents is the ubiquitous overuse of screens, but it is unclear how screen time is related to important mental health outcomes and whether this association differs by gender, age and screen type.

Methods

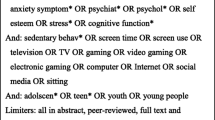

Medline/PubMed, PsychINFO and Google Scholar databases were searched on December 2019 for articles published mainly in the last 5 years. The search focused on two main concepts: (i) screen time and (ii) mental health outcomes including anxiety, depression, psychological and psychosocial well-being and body image concerns.

Results

Sixty studies were included in the review. Higher levels of screen time were associated with more severe depressive symptoms. We found moderate evidence for an association between screen time and poor psychological well-being and body dissatisfaction especially among females. Relationships between screen time and anxiety were inconsistent and somewhat gender specific. Social media use was consistently associated with poorer mental health.

Summary

Higher levels of screen time are generally associated with poorer mental health outcomes, but associations are influenced by screen type, gender and age. Practitioners, parents, policy makers and researchers should collectively identify and evaluate strategies to reduce screen time, or to use screens more adaptively, as a means of promoting better mental health among children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, 13.4% of children and adolescents experience mental health disorders [1], indicating that adolescents are at high risk. In fact, 70% of mental illnesses start in early ages [2], and many persist into adulthood [3]. These statistics are alarming given that mental disorders contribute 21.8% of the total burden of disease in high-income countries among children and adolescents aged 0–14 years [4] and can reduce life expectancy by 20 years [5], thus leading to premature mortality.

Sedentary behaviour is defined as any waking activities that result in an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) while in either a sitting, lying or reclining posture [6]. It includes most sitting-based activities (e.g. reading, eating, listening to music, drawing, etc.) and screen-based leisure time activities (e.g. TV viewing, playing video games, use of computers, cellular phones, tablets and social media) [7,8,9]. Sedentary behaviour can be measured objectively using accelerometers, which offer an accurate measurement of total sedentary time, and subjectively using questionnaires and diaries which provide detailed information on the quality, context and type of sedentary behaviour [10, 11]. Sedentary behaviour, primarily in the form of screen use among children and adolescents, has increased dramatically in the past decade with the advent of mobile technology, with the majority of youth spending large proportions of the day (6–8 h) in this type of sedentary activity [12, 13].

It has been recognised that sedentary behaviour has detrimental health effects, including adverse cardiometabolic health outcomes, morbidity and premature mortality [14,15,16,17]. Indeed, high levels of sedentary behaviours are correlated with many adverse health outcomes in children and adolescents, including physical and mental well-being [18], elevated body mass index (BMI) [19,20,21], cardiometabolic function [21, 22] and cognitive development [20]. In this context, Canadian and international guidelines established recommendations to limit the time spent engaged in sedentary pursuits [23,24,25,26]. For example, the Canadian 24-h movement guidelines for children and adolescents discourage screen time for children under 2 years old and suggest no more than 1 h daily for children 2–4 years and no more than 2 h for those aged 5–17 years old [27]. Despite these recommendations, the vast majority of children and adolescents do not meet these guidelines and engage in high levels of screen time, with many accruing between 6 and 8 h/day [9, 12, 13, 28,29,30,31,32].

Surprisingly, findings from a recent systematic review found limited evidence to show that objectively measured sedentary behaviour has a negative impact on mental health [33]. However, objectively measured sedentary behaviour combines screen time and many non-screen sedentary behaviours such as reading, homework, listening to music and other sedentary hobbies, so the effects of screen time on mental health have not been adequately isolated. There are many inherent aspects of spending long periods engaged in screen use that can lead to poor mental health, including feelings of social isolation or withdrawal, exposure to unrealistic ideals of beauty, unhealthy social comparisons, sleep reduction and cyberbullying [22, 34,35,36,37]. Moreover, there is evidence that different types of screen use may have different impacts on health [38], indicating that the type of screen matters, although this has not been well studied. Research has indicated that digital media users have different needs that impact the selection and the preference of media [39]. According to the differential-susceptibility model proposed by Valkenburg and Peter [40], the effects of media are dependent on a complex combination of cognitive (effort invested), physiological (stimulation received), behavioural (frequency/duration of use) and personality characteristics, which collectively lead individual differences in susceptibility of harmful effects of media consumption [40].

Therefore, given the high prevalence of screen time and mental health problems among children and adolescents and their significant economic [41, 42] and health impact they pose [43, 44], it is timely to better understand how screen time among children and adolescents is related to important mental health outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, body image and psychological well-being. Accordingly, this narrative review aimed to synthesise research in this area, including research using both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs to establish an evidence base that can inform policy, practice and research regarding the psychological impacts that screen use has on children and adolescents.

Methods

Electronic databases of Medline/PubMed, PsychINFO and Google Scholar were searched on December 2019 for articles published in the last 5 years. The search mainly focused on the association between recreational screen time sedentary behaviour and mental health outcomes in children and adolescents including anxiety, depression, psychological and psychosocial well-being and body image concerns. Then the articles’ titles and abstracts were screened, and full text of potentially relevant articles were retrieved according to eligibility criteria. Information was extracted from each article and summarised in tables categorised by to the study outcomes. A total of 60 articles met the inclusion criteria. Included studies were heterogeneous and varied in terms of the screen time activities including age, sample size and outcome measures.

Cross-sectional Studies on the Association Between Screen Time and Depressive Symptoms

Depression and anxiety are considered to be among the leading causes of illness, disability and burden in youth according to the World Health Organization [45, 46]. The prevalence of depression increased by 18% [47] between 2005 and 2015, and up to 20% of children and adolescents to meet criteria for anxiety disorders [48]. This is highly concerning especially with emerging research indicating that the onset of depression and anxiety is occurring at younger ages [49,50,51].

Many cross-sectional studies [36, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] (Table 1) have examined the relationship between screen time and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety among children and adolescents. Out of 23 cross-sectional studies, the majority of studies (n = 17) showed that high exposure to at least one type of screen use was associated with more severe depression and/or anxiety symptoms [36, 52, 53, 57, 59,60,61,62,63,64, 67•, 68,69,70,71,72,73], while only a few studies reported negative associations [58] or mixed associations based on gender [54, 55, 56•, 65, 66]. Research on preschooler’s screen time and mental health such as depression and anxiety is lacking.

In cross-sectional studies, almost all types of screen use were significantly associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms among young people, especially adolescents, with aggregated time spent engaged in television, computer and mobile phone use showing the strongest associations, indicating an additive effect of screen use. For example, one of the largest cross-sectional studies (n = 9702) [53] on adolescents found that screen use was associated with an increased odds of moderate and severe symptoms of depression and anxiety. These results were similar to other large cross-sectional studies [60, 63]. Maras et al. demonstrated that higher levels of screen time, as measured by an aggregate of TV viewing, recreational computer use and video gaming, were associated with more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety among the youth [60], consistent with cross-sectional findings from other studies among children and adolescents [52, 61, 75, 76]. Associations with emotional distress may differ by screen type, as leisure computer use was more highly associated with anxiety and depression outcomes than television viewing in some studies [52, 60], but cross-sectional findings from a longitudinal study found that high levels of TV viewing and not recreational computer use were more strongly associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents and children [74].

Internet-based video gaming has recently become a popular activity among adolescents, especially males, making it an important type of sedentary behaviour to investigate. A recent study on 578 adolescents reported that high use of internet video gaming was associated with more severe anxiety and depression among adolescents, with males being more affected than females [65]. These results are consistent with other studies showing a strong association between computer games and symptoms of depression [52, 60]. However, a recent European study on gaming among school children between 6 and 11 years found that gaming was not significantly associated with self-reported mental health problems such as depression and anxiety [58]. The conflicting findings may be due, in part, to differences in “dose” of video gaming and age, as the studies with adolescents reported much higher usage of gaming compared with those involving pre-adolescent samples.

In addition to online video gaming, new digital media like social media networking sites have also been recognised to be associated with mental health issues like depression and/or anxiety [36, 56•, 67•, 68,69,70,71,72,73]. A recent nationally representative study [56•] reported that adolescents who frequently use social media were more likely to have high levels of depressive symptoms, with stronger correlations reported among females. The association between social networking sites (SNS), psychological distress and suicide attempts was found to be indirect and mediated by cyberbullying victimisation in a large study (N = 5126) of adolescents (aged 11–20 years) [36]. Insomnia was another mediating factor reported by Li et al., who found a positive association between Facebook addiction and depression among 1015 Chinese adolescents [72]. Furthermore, another cross-sectional study indicated that both active and passive use of Facebook were associated with an increased depressed mood. However, this association was influenced by gender where girls who use Facebook passively and boys who use Facebook actively in a public setting were more likely to develop depression. Also, this study indicated that perceived social support mediated the relationship between social media and depression [69]. The number of social media accounts and the frequency of checking were also found to be additional factors that impact the association between social media and depression and anxiety according to data from parents [70]. These factors and mediators require further investigation in future research.

Concerning the age group, the majority of studies assessed screen use and depression among adolescents, or combined children and adolescents without examining these populations separately, so associations in children are unclear. The greater inquiry in adolescents might be attributed to adolescents reporting higher screen use than children [89] or being more prone to experiencing depression than children [90].

Longitudinal Studies on Screen Use and Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms

Several longitudinal studies examined the association between screen time and depression and anxiety among children and adolescents [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] (Table 1). Some recent studies were in line with cross-sectional ones and found a positive association between screen use, depression [74, 77•] and anxiety among adolescents [85, 88]. For example, a longitudinal study done on 3826 adolescents found a time-varying relationship between social media, television and depressive symptoms [77•]. Each additional hour spent on social media usage in a given year was linked to a 0.41-unit increase in depressive symptoms for that same year, indicating a dose–response relationship. Also, a similar within-person association was found with television watching [77•]. Furthermore, a large longitudinal study with 6595 adolescents aged 12 to 15 years old reported that spending more than 3 h daily on social media significantly increased the risk for mental health problems, particularly internalising problems such as depression and anxiety [85]. While 8 longitudinal studies [74, 77•, 79, 82, 85,86,87,88] found an association between some types of screen activities and depression and/or anxiety, other studies found little [78, 80, 81] or no evidence [75, 76, 83] that screen time is longitudinally associated with depression and/or anxiety. For example, a longitudinal study involving children and adolescents that examined the association between television watching and mental health indicated no significant association [83].

Interestingly, many cross-sectional and longitudinal studies found that the association between screen time and depression [54, 55, 56•] and anxiety [84•] differed by gender. Many studies found that females with high levels of screen time use reported the highest level of depressive symptoms, while weaker or even no associations were found in males [54, 55]. Another study found higher symptoms of anxiety with playing video games among girls and lower symptoms among boys [84•] which contradicts the findings from Wang et al. [65] who reported that high online video game use was related to higher symptoms of depression and anxiety among males. It should be noted that the sample of youth from the study by Wang et al. engaged significantly in more time of online gaming, thereby highlighting that video gaming may be especially psychologically harmful with excessive use.

The difference in results and clear gender differences in longitudinal studies might be related to diverse types of screen use, dose, age and variation in the baseline level of anxiety and depression among adolescents. For example, a study by Kelly et al. in 2018 involved 10,904 adolescents, indicating that females spent a high proportion of their time on social media and that the magnitude of association between social media use and depressive symptoms was larger for females than for males [56•], consistent with the findings in similar studies and reviews [87••, 91]. Research has indicated that high social media use may confer an increased risk of depression in adolescent females due to interference in sleep habits [37], exposure to teasing or cyberbullying or unrealistic beauty ideals leading to unfavourable social comparisons and low self-esteem [92]. These gender differences might also be related, in part, to the higher baseline levels of anxiety/depression among adolescent females than males [93] as the prevalence of depression and anxiety after puberty is twice as high for females compared with males [94], as well as a higher prevalence of social media use among adolescent girls.

Although consistent gender differences emerged for social media use, a recent longitudinal study on video games and anxiety among older adolescents showed that while moderate use of video gaming was associated with higher anxiety symptoms among females, this was not the case in males [84•]. While the reason is still unclear, the authors hypothesise that boys may enjoy the social interaction and sense of competition between players more than girls. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the degree of internet usage or video game “dose” may have an important impact on affective symptoms, as youth with extensive screen exposure in the form of internet use/video gaming exhibited significantly more mental health issues than those with low usage, regardless of gender [95].

Very few studies have examined reciprocal relationships between screen time and depression and anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents. However, a large longitudinal study among adolescents showed a reciprocal relationship between computer and videogame usage and increased level of generalised anxiety disorders [88]. That is, youth with emotional distress characterised by anxiety may spend more time indoors and engage in various forms of screen time as a way of coping, and these media activities may further exacerbate their psychological distress, thereby creating a vicious cycle.

In summary, there is strong cross-sectional and moderate longitudinal evidence for an association between screen time and depressive symptoms among children and adolescents, but associations differ by age, type of screen use, gender and other moderators. Most of the studies focused on depressive symptoms, so further longitudinal studies are warranted to better understand the association between different types of screen time and anxiety.

Cross-sectional Studies on Screen Time and Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being refers to satisfaction with life and experiencing positive emotions [96], including positive self-perceptions and positive relationships [97]. Research has linked psychological well-being with academic performance [98], physical health [99] and mental health. Thus, it is essential to understand how screen time is associated with psychological well-being among children and adolescents to effectively inform clinical practice, policy and research.

As shown in Table 2, several cross-sectional studies examined the role of screen time on childrens and adolescents’ well-being [63, 64, 100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107]. Negative associations between digital technology use and adolescents’ and childrens’ well-being were found in many studies [63, 64, 100, 101, 105,106,107], while a few found no relationship between the use of screen time and well-being [102,103,104]. A high-quality, large study (n = 120,115) in youth from the UK found that moderate digital technology use did not correlate strongly with mental well-being [103]. However, analysis of three large surveys of adolescents in the UK and USA (n = 221,096) [64] revealed that those who use screens for less than 1 h a day reported more favourable psychological well-being than high users (more than 5 h/day). Interestingly, this study indicated that individuals who did not engage in digital media activities at all had poorer well-being than light users [64].

While results were more consistent among adolescents, studies on young children reported mixed findings. A cross-sectional study in China looked at the relationship between excessive screen time and psychological well-being in 20,324 children aged 3–4 years found a dose–response relationship whereby every additional hour of screen-based pursuits was associated with poorer psychosocial well-being. This association was mostly mediated by the parent–child interaction. According to this study, excessive exposure to screen may have the strongest effect on the frequency of engagement in interactive activities between the parents and the child which in turn can be a risk factor for child psychosocial problems [106•]. On the other hand, null findings were reported in a smaller study examining the associations between moderate levels of TV viewing and psychological well-being among children aged 0–5 years [102]. Similarly, in a large cross-sectional study (n = 19,957), little or no evidence was found to support a link between screen use and psychological well-being among young children [104].

Longitudinal Studies on Screen Time and Psychological Well-Being

Several longitudinal studies (Table 2) have found that higher amounts of recreational screen time predicted lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents [87••, 107,108,109,110,111,112]. A study investigated possible dose–response associations between media use and later psychological well-being among children aged between 2 and 6 years. This study reported that higher levels of electronic media predicted lower psychological well-being, with television viewing being more strongly associated with well-being than e-games and computer use [110]. Another longitudinal study indicated that the high use of social media was associated with poorer well-being, and the relationship was stronger for females than males [87••, 109••]. This gender difference was also apparent in other studies examining the effect of excessive use of video gaming, also called video gaming disorder on psychological and psychosocial well-being. A recent longitudinal study found that video gaming disorder predicted a decrease in psychosocial well-being especially social competencies among boys compared to girls [112]. Similar to those stated above for anxiety and depression, mechanisms underpinning this gender difference might simply reflect differences in use between females and males [87••, 91] which leads to a higher risk of being exposed to cyberbullying [56•, 87••, 113, 114]. Also, the types of games chosen might be associated with gender differences as girls tend to choose puzzle and educational games while boys tend to choose fighting, strategy and action games which might increase their vulnerability to the negative impact of disordered gaming [115]. Another possible mechanism that may explain the association between screen time and mental well-being is sleep, as inadequate sleep is associated with higher use of screen time among children and adolescents [116]; thus, the displacement of sleep, especially among girls, can mediate the association between screen time and mental well-being [56•, 87••]. Furthermore, replacing direct interaction with friends with low-quality, superficial communication of most online interaction online interaction may result in poor social connectedness and lower quality of relationships, which consequently may negatively affect psychological well-being [117].

Taken together, the majority of the reviewed studies, including those using longitudinal designs, indicate a negative association between screen time and psychological well-being, with most of the studies being conducted in adolescents. More inconsistent results emerged from large-scale cross-sectional studies, perhaps due to greater heterogeneity in study measures of well-being, data analyses and sample characteristics [102, 104]. The evidence base among pre-adolescents and young children is moderate, but we highly recommend further longitudinal examination of the relationship between screen time and psychological well-being is needed to gain a better understanding of this association.

Cross-sectional Studies on Screen Time and Body Image

Body dissatisfaction is defined as a negative attitude towards appearance, body weight, size or shape and is one the most robust aspects of the broader concept of body image. Body image concerns are highly prevalent during adolescence when one’s body shape and weight strongly influence one’s self-esteem, and these concerns are especially salient among females [118]. Body image concerns are well known to be detrimental contributors to well-being [119] and significant predictors of psychiatric conditions such as eating disorders and [118] and depression, as well as low self-esteem [120, 121]. With social media platforms such as Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram, body image has become an important target in these activities [122], where individuals post their most flattering photos and view those of others [123], creating an online environment that could be detrimental to body image [124]. Spending time on social media puts adolescents under a higher risk of comparing themselves to more attractive peers [125], and as a result, these unfavourable social comparisons of physical appearance may elicit or exacerbate body image concerns [126, 127]. Screen time, mainly social media use, has received significant attention in research for its potential impact on body dissatisfaction [128]; therefore, it is highly essential to understand how the use of this and other forms of digital media may contribute to adolescents’ body image.

As shown in Table 3, cross-sectional research indicated that screen time [56•, 126, 129,130,131,132,133] especially that spent on social media is associated with body image concerns among adolescents. For example, a large study comprised of high school girls (n = 1087) aged 13–15 years showed that those who use social media frequently reported significantly greater body image concerns such as internalisation of the thin ideal, drive for thinness and body surveillance compared to non-users [131]. Another recent cross-sectional study among adolescents [130] also indicated an association between social media and body dissatisfaction; however, this study found that this association was impacted by the social environment (e.g. relationship with the mother). Specifically, adolescents who reported positive relationships with their mothers had less body dissatisfaction in relation to social media use than those with more negative maternal relationships [130].

Longitudinal Studies on Screen Time and Body Image

Although many cross-sectional [126, 131,132,133] and longitudinal research [136] has focused on females who report high levels of body image concerns, some recent longitudinal studies included both genders [134, 135•]. For example, a study on 604 adolescents aged 11–18 years indicated that both genders experienced the same extent of body dissatisfaction when using social media networking sites frequently [134]. Another longitudinal study involving 1840 adolescents aged between 12 and 19 years showed that passive Facebook usage (consuming information without direct exchanges like posting status or commenting) was associated with more social comparison among adolescent males and females over time [135•]. While social comparison has been clearly implicated in playing an important mechanistic role in the association between screen time and body image concerns, other factors were highlighted in the literature as indicated previously about the buffering effects of positive parent–adolescent relationships [130].

Interestingly, media literacy, which is about being able to think critically about media [137] and being able to assess whether a media content such as an image is realistic or not [138], was suggested as another important protective factor that attenuated the adverse effects on body image among adolescents when exposed to unrealistic thin-ideal media images [139]. Thus, media literacy programs should be examined in more depth using experimental and longitudinal designs as this may represent a promising strategy that protects youth from developing an unhealthy body image known to predict other psychiatric disorders.

Limitations and Strengths

Although this narrative review is representative of key findings from a broad body of literature with the aim to examine the research objectives, there are a few limitations that are noteworthy. This study was not a systematic review of the literature, but rather a narrative review performed by a single reviewer. There may be relevant studies that have been excluded. However, the present review is unique in critically analysing both cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from very recent studies (past 5 years) about the association between sedentary screen time and mental health, thus providing current evidence to inform future research, practice and policy reform designed to improve children’s and adolescents’ mental health.

Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

Findings from the present review suggest that screen time is generally associated with depressive symptoms among adolescents, especially females. Evidence on the association between screen time and anxiety among adolescents was mixed and inconclusive and somewhat screen and gender dependent. However, high screen use was consistently shown to be associated with poorer emotional well-being in longitudinal studies, although mixed evidence was found among cross-sectional studies, especially among young children. We also found that high screen time, especially social media use, was consistently associated with greater body image concerns among both male and female adolescents, although females appear more negatively affected. Media literacy and positive relationship with parents appear to attenuate the negative role of screen time on body image, likely by reducing internalisation of unrealistic beauty ideals. Due to the small number of studies in pre-adolescent children, especially preschoolers, it is not possible to determine with any degree of confidence the association between screen time and mental health indicators in this population.

This review highlights that some types of screens are more consistently problematic for mental health than others depending on the content of the media and the characteristics of individuals and their susceptibility levels to the effects of media. For example, social media usage was consistently shown to be associated with depressive and/or anxiety symptoms [36, 56•, 67•, 68,69,70,71,72,73, 82, 86], higher levels of body dissatisfaction [56•, 130,131,132, 134,135,136] and poorer psychological well-being [87••, 109••, 111, 112] among adolescents, with evidence showing that these relationships are sometimes stronger in girls than boys. Regarding mechanisms in which social media may negatively affect mental health, evidence suggests this may occur through a process of unfavourable social comparison, poor sleep and/or cyberbullying [22, 34,35,36, 69, 72]. Although not well studied, the preliminary research among adolescents, especially males, suggests that high use of internet video gaming is associated with more severe anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence to suggest that excessive internet-based gaming can produce marked interference in youth’s emotional, familial, social and academic functioning and is being evaluated for inclusion as a behavioural addiction in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) [140]. Similarly, this review found evidence for associations between excessive computer/internet use and mental health difficulties in adolescents. These findings are consistent with the introduction of new concepts known as “internet addiction disorder” or “internet use disorder”, which are additional types of behavioural addictions characterised by compulsive or pathological internet use that result in marked impairment in functioning. These terms are also being considered for inclusion in the DSM-V [140].

Recommendations for Practice, Policy and Research

Given that childhood and adolescence are critical periods for physical and psychological development, and children and adolescents are spending excessive amounts of time in recreational screen use, the results of this review have significant implications. Based on evidence from this review, we recommend that parents and health practitioners who work with children and adolescents limit recreational screen use to that delineated in the Canadian 24-h movement behaviour guidelines [27]. The findings obtained here also support the new changes in school policy made by the Provincial Ministry of Education in Ontario, Canada, that banned the use of cell phones in schools. Given screen time is associated with an increased risk of obesity [19,20,21] and cardiometabolic disease [21, 22] in children and adolescence, and this review provides robust evidence for detrimental associations with several mental health outcomes, further legislation by other provinces around banning cell phones may follow and these policy changes should be empirically evaluated to see if they have beneficial effects on mental health. There is encouraging evidence that media literacy may be an effective method in which parents, teachers and practitioners can attenuate the harmful effects of digital media use, although more intervention studies are needed. Moreover, developing and maintaining a strong parent–child relationship appears to buffer the negative effects of screen time on several mental health indicators, thus should be targeted in treatment and prevention studies.

Many of the studies used cross-sectional designs, so future longitudinal studies with longer follow-ups and inclusion of potential mediators and moderators including the individuals’ cognitive and emotional statuses that happen during media exposure [40] are needed to gain a better understanding of how various forms of screen use impact children’s and adolescents’ risk of mental health problems over time, and whether effects and mechanisms differ between males and females. In addition, intervention studies designed to determine whether reducing either specific types or duration of screen time or promoting more adaptive use of screens are effective strategies that promote better mental health or prevent mental illness among children and adolescents are needed.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:345–65.

The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada, 2006: (611102012-001) [Internet]. American Psychological Association; 2006 [cited 2019 Dec 5]. Available from: http://doi.apa.org/get-pe-doi.cfm?doi=10.1037/e611102012-001

Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–8.

Gore FM, Bloem PJN, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:2093–102.

Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:153–60.

Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours.”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:540–2.

Pettee Gabriel KK, Morrow JR, Woolsey A-LT. Framework for physical activity as a complex and multidimensional behavior. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(Suppl 1):S11–8.

Troiano RP, Pettee Gabriel KK, Welk GJ, Owen N, Sternfeld B. Reported physical activity and sedentary behavior: why do you ask? J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(Suppl 1):S68–75.

Arundell L, Fletcher E, Salmon J, Veitch J, Hinkley T. A systematic review of the prevalence of sedentary behavior during the after-school period among children aged 5-18 years. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:1–9.

Lubans DR, Hesketh K, Cliff DP, Barnett LM, Salmon J, Dollman J, et al. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of sedentary behaviour measures used with children and adolescents. Obes Rev. 2011;12:781–99.

Atkin AJ, Gorely T, Clemes SA, Yates T, Edwardson C, Brage S, et al. Methods of measurement in epidemiology: sedentary behaviour. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1460–71.

Bauman AE, Petersen CB, Blond K, Rangul V, Hardy LL. The descriptive epidemiology of sedentary behaviour. In: Leitzmann MF, Jochem C, Schmid D, editors. Sedentary behaviour epidemiology [internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 19]. p. 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61552-3_4.

Khan A, Uddin R, Lee E-Y, Tremblay MS. Sitting time among adolescents across 26 Asia–Pacific countries: a population-based study. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:1129–38.

Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:123–32.

Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sá TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:811–29.

Hebestreit A, Thumann B, Wolters M, Bucksch J, Huybrechts I, Inchley J, et al. Road map towards a harmonized pan-European surveillance of obesity-related lifestyle behaviours and their determinants in children and adolescents. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:615–23.

Pogrmilovic BK, O’Sullivan G, Milton K, Biddle SJH, Bauman A, Bull F, et al. A global systematic scoping review of studies analysing indicators, development, and content of national-level physical activity and sedentary behaviour policies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:1–17.

LeBlanc AG, Spence JC, Carson V, Connor Gorber S, Dillman C, Janssen I, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:753–72.

Fang K, Mu M, Liu K, He Y. Screen time and childhood overweight/obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2019;45:744–53.

Mitchell JA, Rodriguez D, Schmitz KH, Audrain-McGovern J. Greater screen time is associated with adolescent obesity: a longitudinal study of the BMI distribution from ages 14 to 181 2. Obesity. 2013;21:572–5.

Goldfield GS, Kenny GP, Hadjiyannakis S, Phillips P, Alberga AS, Saunders TJ, et al. Video game playing is independently associated with blood pressure and lipids in overweight and obese adolescents. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26643.

Saunders TJ, Chaput J-P, Tremblay MS. Sedentary behaviour as an emerging risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases in children and youth. Can J Diabetes. 2014;38:53–61.

WHO adolescent mental health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

Australia Co. Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children (5-12 years) and Young People (13-17 years): An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. 2019. p. 148.

Tremblay MS, Chaput J-P, Adamo KB, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Choquette L, et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years (0–4 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017;17 [cited 2019 Feb 22]. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4859-6.

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Carson V, Choquette L, Connor Gorber S, Dillman C, et al. Canadian physical activity guidelines for the early years (aged 0–4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:345–56.

Tremblay MS, Carson V, Chaput J-P, Connor Gorber S, Dinh T, Duggan M, et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:S311–27.

Downing KL, Hnatiuk J, Hesketh KD. Prevalence of sedentary behavior in children under 2 years: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;78:105–14.

Vanderloo LM. Screen-viewing among preschoolers in childcare: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:205.

O’Brien KT, Vanderloo LM, Bruijns BA, Truelove S, Tucker P. Physical activity and sedentary time among preschoolers in centre-based childcare: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity [Internet]. 2018;15 [cited 2019 Feb 22] Available from: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-018-0745-6.

Pereira JR, Cliff DP, Sousa-Sá E, Zhang Z, Santos R. Prevalence of objectively measured sedentary behavior in early years: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29:308–28.

Ferrari GL d M, Pires C, Solé D, Matsudo V, Katzmarzyk PT, Fisberg M. Factors associated with objectively measured total sedentary time and screen time in children aged 9–11 years. J Pediatr. 2019;95:94–105.

Cliff DP, Hesketh KD, Vella SA, Hinkley T, Tsiros MD, Ridgers ND, et al. Objectively measured sedentary behaviour and health and development in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:330–44.

Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukopadhyay T, Scherlis W. Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol. 1998;53:1017–31.

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA, Chaput J-P. Use of social media is associated with short sleep duration in a dose-response manner in students aged 11 to 20 years. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107:694–700.

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA. Social networking sites and mental health problems in adolescents: the mediating role of cyberbullying victimization. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:1021–7.

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Chaput J-P, Hamilton HA, Colman I. Bullying involvement, psychological distress, and short sleep duration among adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53:1371–80.

Sanders T, Parker PD, del Pozo-Cruz B, Noetel M, Lonsdale C. Type of screen time moderates effects on outcomes in 4013 children: evidence from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act BioMed Central. 2019;16:1–10.

Rentfrow PJ, Goldberg LR, Zilca RD. Listening, watching, and reading: the structure and correlates of entertainment preferences. J Pers. 2011;79:223–58.

Valkenburg PM, Peter J. The differential susceptibility to media effects model. J Commun Oxford Academic. 2013;63:221–43.

Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:23–33.

Snell T, Knapp M, Healey A, Guglani S, Evans-Lacko S, Fernandez J-L, et al. Economic impact of childhood psychiatric disorder on public sector services in Britain: estimates from national survey data. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:977–85.

Jokela M, Ferrie J, Kivimäki M. Childhood problem behaviors and death by midlife: the British National Child Development Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:19–24.

Knapp M, King D, Healey A, Thomas C. Economic outcomes in adulthood and their associations with antisocial conduct, attention deficit and anxiety problems in childhood. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2011;14:137–47.

Patel V. Why adolescent depression is a global health priority and what we should do about it. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:511–2.

Dick B, Ferguson BJ. Health for the world’s adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:3–6.

World Health Organization. WHO | Depression: let’s talk [Internet]. WHO. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/en/

Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005;14:631–48.

Sorenson SB, Rutter CM, Aneshensel CS. Depression in the community: an investigation into age of onset. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:541–6.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602.

Yalin N, Young A. The Age of Onset of Unipolar Depression: Etiopathogenetic and Treatment Implications. Springer, Cham, 2019. p. 111–24.

Goldfield GS, Murray M, Maras D, Wilson AL, Phillips P, Kenny GP, et al. Screen time is associated with depressive symptomatology among obese adolescents: a HEARTY study. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175:909–19.

Bélair M-A, Kohen DE, Kingsbury M, Colman I. Relationship between leisure time physical activity, sedentary behaviour and symptoms of depression and anxiety: evidence from a population-based sample of Canadian adolescents. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021119.

Hayward J, Jacka FN, Skouteris H, Millar L, Strugnell C, Swinburn BA, et al. Lifestyle factors and adolescent depressive symptomatology: associations and effect sizes of diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:1064–73.

Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, Allender S. Depression, psychological distress and internet use among community-based Australian adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:365.

• Kelly Y, Zilanawala A, Booker C, Sacker A. Social media use and adolescent mental health: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine. 2018;6:59–68 A large representative study which examines various mechanisms which have been proposed as pathways for the association between social media and adolescent’s mental health. (online harassment, sleep quantity, self-esteem, body image).

Khan A, Burton NW. Is physical inactivity associated with depressive symptoms among adolescents with high screen time? Evidence from a developing country. Ment Health Phys Act. 2017;12:94–9.

Kovess-Masfety V, Keyes K, Hamilton A, Hanson G, Bitfoi A, Golitz D, et al. Is time spent playing video games associated with mental health, cognitive and social skills in young children? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:349–57.

Li X, Buxton OM, Lee S, Chang A-M, Berger LM, Hale L. Sleep mediates the association between adolescent screen time and depressive symptoms. Sleep Med. 2019;57:51–60.

Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, et al. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev Med. 2015;73:133–8.

Trinh L, Wong B, Faulkner GE. The independent and interactive associations of screen time and physical activity on mental health, school connectedness and academic achievement among a population-based sample of youth. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:17–24.

Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6:3–17.

Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:271–83 One of very few large studies to explore the association between screen time and mental health on children and adolescents from a very young age.

Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Media use is linked to lower psychological well-being: evidence from three datasets. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90:311–31.

Wang J-L, Sheng J-R, Wang H-Z. The association between mobile game addiction and depression, social anxiety, and loneliness. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2019;7 [cited 2020 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00247/full.

Zhang J, Hu H, Hennessy D, Zhao S, Zhang Y. Digital media and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Heliyon [Internet]. 2019;5 [cited 2020 Jan 7] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6514493/.

• Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Lewis RF. Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18:380–5 A very large representative study which examines mainly the mediating role of cyberbullying on adolescent’s mental health.

Hanprathet N, Manwong M, Khumsri J, Yingyeun R, Phanasathit M. Facebook addiction and its relationship with mental health among Thai high school students. J Med Assoc Thailand Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2015;98:S81–90.

Frison E, Eggermont S. exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2016;34:153–171.

Barry C, Sidoti C, Briggs S, Reiter S, Lindsey R. Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. J Adolesc. 2017;61:1–11.

Yan H, Zhang R, Oniffrey T, Chen G, Wang Y, Wu Y, et al. Associations among screen time and unhealthy behaviors, academic performance, and well-being in Chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:596.

Li J-B, Lau JTF, Mo PKH, Su X-F, Tang J, Qin Z-G, et al. Insomnia partially mediated the association between problematic internet use and depression among secondary school students in China. J Behav Addict Akademiai Kiado. 2017;6:554–64.

Wang P, Wang X, Yingqiu W, Xie X, Wang X, Zhao F, et al. Social networking sites addiction and adolescent depression: a moderated mediation model of rumination and self-esteem. Personal Individ Differ. 2018;127:162–7.

Bickham DS, Hswen Y, Rich M. Media use and depression: exposure, household rules, and symptoms among young adolescents in the USA. Int J Public Health. 2015;60:147–55.

Carter JS, Dellucci T, Turek C, Mir S. Predicting depressive symptoms and weight from adolescence to adulthood: stressors and the role of protective factors. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:2122–40.

Gunnell KE, Flament MF, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, Schubert N, et al. Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Prev Med. 2016;88:147–52.

• Boers E, Afzali MH, Newton N, Conrod P. Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:853–9 A large longitudinal study with a long term follow-up which examines various types of screen activities effects on adolescent’s mental health.

Etchells PJ, Gage SH, Rutherford AD, Munafò MR. Prospective investigation of video game use in children and subsequent conduct disorder and depression using data from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147732.

Grøntved A, Singhammer J, Froberg K, Møller NC, Pan A, Pfeiffer KA, et al. A prospective study of screen time in adolescence and depression symptoms in young adulthood. Prev Med. 2015;81:108–13.

Houghton S, Lawrence D, Hunter SC, Rosenberg M, Zadow C, Wood L, et al. Reciprocal relationships between trajectories of depressive symptoms and screen media use during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47:2453–67.

Khouja JN, Munafò MR, Tilling K, Wiles NJ, Joinson C, Etchells PJ, et al. Is screen time associated with anxiety or depression in young people? Results from a UK birth cohort. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2019;19 [cited 2019 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6337855/.

Li J, Mo P, Lau J, Su X-F, Zhang X, Wu A, et al. Online social networking addiction and depression: the results from a large-scale prospective cohort study in Chinese adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:1–11.

McVeigh J, Smith A, Howie E, Straker L. Trajectories of television watching from childhood to early adulthood and their association with body composition and mental health outcomes in young adults. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152879.

• Ohannessian CM. Video game play and anxiety during late adolescence: the moderating effects of gender and social context. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:216–9 A longitudinal study that considers gender and the social context of video game use on anxiety symptomatology.

Riehm KE, Feder KA, Tormohlen KN, Crum RM, Young AS, Green KM, et al. Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1266–73.

Vernon L, Modecki K, Barber B. Tracking effects of problematic social networking on adolescent psychopathology: the mediating role of sleep disruptions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;46:1–15.

•• Viner R, Gireesh A, Stiglic N, Hudson L, Goddings A-L, Ward J, et al. Roles of cyberbullying, sleep, and physical activity in mediating the effects of social media use on mental health and wellbeing among young people in England: a secondary analysis of longitudinal data. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2019;3:685–696. This study is the first longitudinal mediation analysis from a representative cohort which highlights that the impact of social media on is not directly associated with social media use but with the content or the displacement of sleep and physical activity.

Zink J, Belcher BR, Kechter A, Stone MD, Leventhal AM. Reciprocal associations between screen time and emotional disorder symptoms during adolescence. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:281–8.

Brodersen NH, Steptoe A, Boniface DR, Wardle J. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in adolescence: ethnic and socioeconomic differences. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:140–4.

Lack CW, Green AL. Mood disorders in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24:13–25.

McCrae N, Gettings S, Purssell E. Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Adolescent Res Rev. 2017;2:315–30.

Kim S, Kimber M, Boyle MH, Georgiades K. Sex differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Can J Psychiatr. 2019;64:126–35.

Sadler K, Vizard T, Ford T, Marchesell F, Pearce N, Mandalia D, et al. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017. [Internet]. NHS Digital. 2017; [cited 2019 Dec 16]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017.

Giedd JN, Keshavan M, Paus T. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–57.

Yen J-Y, Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Chen S-H, Chung W-L, Chen C-C. Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with internet addiction: comparison with substance use. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:9–16.

Diener E. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000;55:34–43.

Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. 1995;69:719.

Rodríguez-Fernández A, Ramos-Díaz E, Axpe-Saez I. The role of resilience and psychological well-being in school engagement and perceived academic performance: an exploratory model to improve academic achievement. Health and Academic Achievement [Internet]. 2018; [cited 2019 Dec 16]; Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/health-and-academic-achievement/the-role-of-resilience-and-psychological-well-being-in-school-engagement-and-perceived-academic-perf.

Hernandez R, Bassett SM, Boughton SW, Schuette SA, Shiu EW, Moskowitz JT. Psychological well-being and physical health: associations, mechanisms, and future directions. Emot Rev. 2018;10:18–29.

Booker CL, Skew AJ, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Media use, sports participation, and well-being in adolescence: cross-sectional findings from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:173–9.

Herman KM, Hopman WM, Sabiston CM. Physical activity, screen time and self-rated health and mental health in Canadian adolescents. Prev Med. 2015;73:112–6.

Lee E-Y, Carson V. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and psychosocial well-being among young south Korean children. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44:108–16.

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N. A large-scale test of the Goldilocks hypothesis: quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychol Sci. 2017;28:204–15.

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N. Digital screen time limits and young children’s psychological well-being: evidence from a population-based study. Child Dev. 2019;90:e56–65.

Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, läuft Study Group. Sedentary behavior, depressed affect, and indicators of mental well-being in adolescence: does the screen only matter for girls? J Adolesc. 2015;42:50–8.

• Zhao J, Zhang Y, Jiang F, Ip P, Ho FKW, Zhang Y, et al. Excessive screen time and psychosocial well-being: the mediating role of body mass index, sleep duration, and parent-child interaction. J Pediatr. 2018;202:157–162.e1 This study is one of very few studies which examines screen time and psychological well-being among preschool children and the role of some mediators on this association such as the BMI, sleep, and parent-child interaction.

Allen MS, Vella SA. Screen-based sedentary behaviour and psychosocial well-being in childhood: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Ment Health Phys Act. 2015;9:41–7.

Babic MJ, Smith JJ, Morgan PJ, Eather N, Plotnikoff RC, Lubans DR. Longitudinal associations between changes in screen-time and mental health outcomes in adolescents. Ment Health Phys Act. 2017;12:124–31.

•• Booker CL, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10-15 year olds in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:321 This study examines longitudinal data from a large nationally representative sample and estimated models separately by gender. It suggests gender differences in the relationship between social media interaction and mental well-being.

Hinkley T, Verbestel V, Ahrens W, Lissner L, Molnár D, Moreno LA, et al. Early childhood electronic media use as a predictor of poorer well-being: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:485–92.

Kim HH. The impact of online social networking on adolescent psychological well-being (WB): a population-level analysis of Korean school-aged children. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2017;22:364–76.

van den Eijnden R, Koning I, Doornwaard S, van Gurp F, ter Bogt T. The impact of heavy and disordered use of games and social media on adolescents’ psychological, social, and school functioning. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:697–706.

Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, Holmgren HG, Stockdale LA. Instagrowth: a longitudinal growth mixture model of social media time use across adolescence. J Res Adolesc. 2019;29:897–907.

Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, Milne A, Sundar P, et al. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: a scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:770–7.

Phan MH, Jardina JR, Hoyle S, Chaparro BS. Examining the Role of Gender in Video Game Usage, Preference, and Behavior. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. Sage CA: Los Angeles, SAGE Publications Inc; 2012;56:1496–500.

Hale L, Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;21:50–8.

Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Online communication and adolescent well-being: testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. J Comput-Mediat Commun. 2007;12:1169–82.

Bucchianeri MM, Arikian AJ, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body Image. 2013;10:1–7.

Stice E, Bearman SK. Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:597–607.

Goldschmidt AB, Wall M, Choo T-HJ, Becker C, Neumark-Sztainer D. Shared risk factors for mood-, eating-, and weight-related health outcomes. Health Psychol. 2016;35:245–52.

Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME. Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35:539–49.

Siibak A. Constructing the self through the photo selection - visual impression management on social networking websites. Cyberpsychology. 2009;3 [cited 2020 Jan 3] Available from: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4218.

Espinoza G, Juvonen J. The pervasiveness, connectedness, and intrusiveness of social Network site use among young adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:705–9.

Chua THH, Chang L. Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:190–7.

Vandenbroucke S, et al. Vieillir, mais pas tout seul. Une enquête sur la solitude et l’isolement social des personnes âgées en Belgique. Fondat Roi Baudouin [Internet]. 2012; [cited 2019 Sep 17] Available from: https://cdn.uclouvain.be/public/Exports%20reddot/aisbl-generations/documents/DocPart_Etud_VieillirMaisPasToutSeul_2012.pdf.

Meier EP, Gray J. Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:199–206.

Fardouly J, Vartanian LR. Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image. 2015;12:82–8.

Holland G, Tiggemann M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image. 2016;17:100–10.

Añez E, Fornieles-Deu A, Fauquet-Ars J, López-Guimerà G, Puntí-Vidal J, Sánchez-Carracedo D. Body image dissatisfaction, physical activity and screen-time in Spanish adolescents. J Health Psychol. 2018;23:36–47.

de Vries DA, Vossen HGM, Van der Kolk-van der Boom P. Social media and body dissatisfaction: investigating the attenuating role of positive parent–adolescent relationships. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48:527–36.

Tiggemann M, Slater A. NetGirls: the internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:630–3.

Tiggemann M, Slater A. NetTweens: the internet and body image concerns in preteenage girls. J Early Adolesc SAGE Publications Inc. 2014;34:606–20.

Vandenbosch L, Eggermont S. Understanding sexual objectification: a comprehensive approach toward media exposure and girls’ internalization of beauty ideals, self-objectification, and body surveillance: media, adolescent girls, and self-objectification. J Commun. 2012;62:869–87.

de Vries DA, Peter J, de Graaf H, Nikken P. Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: testing a mediation model. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:211–24.

• Rousseau A, Eggermont S, Frison E. The reciprocal and indirect relationships between passive Facebook use, comparison on Facebook, and adolescents’ body dissatisfaction. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;73:336–44 This study examines passive use of Facebook and its association with body image concerns reciprocally. It highlights that passive use of Facebook predicts comparison which in its turn predicts more body dissatisfaction.

Tiggemann M, Slater A. Facebook and body image concern in adolescent girls: a prospective study: Facebook and body image concern. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:80–3.

Silverblatt A. Media Literacy: Keys to Interpreting Media Messages. Praeger; 2001.

Berel S, Irving LM. Media and disturbed eating: an analysis of media influence and implications for prevention. J Prim Prev. 1998;18:415–30.

McLean SA, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Does media literacy mitigate risk for reduced body satisfaction following exposure to thin-ideal media? J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:1678–95.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Fatima Mougharbel declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Gary Goldfield declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mougharbel, F., Goldfield, G.S. Psychological Correlates of Sedentary Screen Time Behaviour Among Children and Adolescents: a Narrative Review. Curr Obes Rep 9, 493–511 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00401-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00401-1