Abstract

Options for approach to hysterectomy include abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. There are well-documented benefits to minimally invasive modes of surgery compared to traditional abdominal procedures. Despite this fact, the majority of hysterectomies in the United States are still performed via laparotomy. With regard to differentiation between the various minimally invasive approaches, it has been consistently demonstrated that robotic hysterectomy procedures are associated with longer operative times and higher cost. However, the available literature is limited by the small number of randomized or prospective studies comparing surgical approach to hysterectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As the most common non-obstetric procedure among women [1], hysterectomy is most frequently performed for the indications of leiomyomata, abnormal uterine bleeding, and endometriosis [2]. It is estimated that up to 45 % of women who reach the age of 70 will have undergone a hysterectomy during their lifetime [2]. Although surgical removal of the uterus was documented in medical writings dating back to the 1st century B.C., it was not until 1813 that Conrad Langenback performed the first planned, successful vaginal hysterectomy. This was followed by the first successful abdominal hysterectomy in 1853 by Walter Burnham [3]. The 20th century was marked by significant advances in anesthesia, antisepsis, and surgical technique [4]. Laparoscopy, which was initially developed in the 1940’s, was applied to hysterectomy in the late 1980s by pioneers Harry Reich and Kurt Semm [5, 6]. Computer-assisted surgery also evolved during the 1990s, and in 2001 the first robotic hysterectomy was performed in Texas [7].

In addition to helping optimize individual patient care, research related to hysterectomy may be used to inform public health decisions. It is, therefore, important to critically compare outcomes related to the various surgical approaches to hysterectomy. In addition, issues of cost must be considered given concerns regarding rising healthcare spending. In this review, the authors will highlight recent, relevant literature regarding outcomes and costs associated with common surgical approaches to hysterectomy for benign disease.

Updated Surveillance Information

In order to draw meaningful conclusions about the impact of various routes of hysterectomy, it is useful to understand the current status of this procedure using surveillance statistics. With analysis of a national inpatient hospitalization database, it is estimated that 433,621 hysterectomy procedures were performed in the United States in 2010 [8••]. This represents a marked decline in hysterectomy volume over time. Case incidence peaked in 2002 when over 600,000 hysterectomies were performed annually in the United States. It is possible that this decline in hysterectomy volume is attributable to increasing use of medical therapies and non-extirpative procedures, or it may reflect a failure to capture outpatient minimally invasive hysterectomy cases using inpatient sampling tools [9].

In addition to the changes in numbers of hysterectomy cases, there is also a shift in the surgical approach with increasing use of laparoscopic and robotic techniques [8••, 10, 11]. In the United States in 2009, it is estimated that 56 % of hysterectomies were completed abdominally, 20.4 % were performed laparoscopically, 18.8 % vaginally, and 4.5 % with robotic assistance [9]. This trend toward fewer overall hysterectomies and a higher percentage of cases being completed in a minimally invasive fashion has implications for both patients and physicians. Resident case experience as reported to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education demonstrates a decreasing exposure to abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy during training, which may in turn affect future practice patterns [12].

Outcomes

A 2009 systematic review on the subject of surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign disease analyzed results from 34 randomized controlled trials [13]. Both vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomies were found to have superior outcomes when compared to the abdominal approach to hysterectomy, including: faster recovery, shorter hospital stay, fewer infections, and lower blood loss. Of note, laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a longer operative time and increased risk of urinary tract injury in this review. It may be that the high risk of urinary tract injury reported in the Cochrane review is reflective of early experience with laparoscopic techniques. Updated information regarding risk of urinary tract injury at the time of hysterectomy from a longitudinal prospective cohort study in Finland demonstrates a marked decrease in risk of ureteral injury with laparoscopic hysterectomy in 2006 as compared to 1996 [14]. In addition, a multicenter case-control study of 135 cases of bladder or ureteral injury and 270 controls found that total abdominal hysterectomy was associated with both bladder and ureteral injury, while laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy was associated with increased risk of ureteral injury [15].

Both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists recommend a vaginal or laparoscopic route whenever feasible [16, 17]. Regarding selection of the surgical approach in more challenging hysterectomy cases, a case control study of patients who underwent either robotic or abdominal hysterectomy for uteri weighing greater than 1,000 grams found decreased blood loss and a shorter hospital stay with the robotic approach, despite a longer operative time [18].

Due to the clear benefits of a non-laparotomic approach to hysterectomy, there is increasing emphasis on differentiation among the various minimally invasive modes. Recent literature comparing vaginal to laparoscopic or robot-assisted hysterectomy includes a randomized trial of 108 women undergoing hysterectomy for myomatous uteri. This study compared total laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy and vaginal hysterectomy; the vaginal approach was associated with faster operative time, less blood loss, and a shorter hospital stay [19]. Looking specifically at women over the age of 65 who underwent vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy, a propensity-matched analysis of 80 patients demonstrated non-inferiority of laparoscopic hysterectomy with improved postoperative course [20]. Further, a prospective study of 60 women who underwent robot-assisted hysterectomy and 34 women who underwent vaginal hysterectomy found reduced blood loss, less pain, and a shorter hospital stay in the robotic group, despite longer operative time in that group [21].

With regard to the comparison of the laparoscopic and the robot-assisted approach to hysterectomy, two randomized trials respectively comprised of 53 and 100 patients demonstrated similar outcomes but longer operative time in the robotic groups [22, 23•]. Even with a randomized trial design; however, it is difficult to escape the issues of innate surgeon experience and preference, which may lead to contradictory findings in certain cases. For example, a large retrospective review of robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy cases found equivalent perioperative outcomes including operative time despite patients in the robotic group having higher mean uterine weight and higher prevalence of severe adhesions and stage III-IV endometriosis [24]. Another retrospective cohort study of over 2,500 patients found a lower risk of readmission among robotic-assisted hysterectomy cases along with a shorter length of stay and less blood loss as compared to laparoscopic, open or vaginal approaches [25]. Using a nationwide United States database for the years 2009 and 2010, a propensity-matched analysis demonstrated similar perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomy; robotic-assistance was associated with a lower incidence of blood transfusion but a higher likelihood of postoperative pneumonia [26••].

Cost

In addition to perioperative outcomes, another important consideration in the current health care climate is that of cost-effectiveness. Healthcare costs are notoriously difficult to define as the true cost of a procedure may encompass more than what is reflected by the hospital charges. For example, when discussing total cost, it is important to include assessment of any related complications, readmissions or associated treatments. Similarly, one may choose to report the cost to society with accounting for lost wages and surgery-associated disability. Despite these challenges, it is critical to consider the economic impact of hysterectomy in light of cost-constrained healthcare systems.

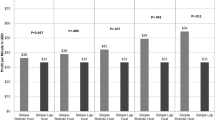

In an attempt to better define the cost of robotic hysterectomy compared to vaginal or abdominal modes, researchers at the Mayo Clinic performed a propensity score matched analysis to estimate hysterectomy-related all-cause costs [27•]. They report that robotic hysterectomy is more costly than vaginal hysterectomy, but similar in cost to abdominal hysterectomy. With the aid of a hospital decision support database, a group of Irish researchers calculated the net hospital income with varying types of minimally invasive hysterectomy and found that vaginal hysterectomy was the only mode that generated net income [28]. A retrospective cost analysis of hysterectomy performed for uteri weighing more than 500 grams at a Korean academic hospital also demonstrated lower total hospital cost with vaginal hysterectomy compared to laparoscopic hysterectomy despite longer hospital stays in the vaginal group [29].

Although introduction of robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery may enable physicians to perform hysterectomy without laparotomy, it is associated with substantially higher cost. A cohort study using national data from 2007-2010 estimated over $2,000 in added cost per case when robot-assistance is employed compared to conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy [10]. These findings were echoed in an analysis of a separate national inpatient database from 2009 and 2010; despite similar perioperative outcomes compared to laparoscopic hysterectomies, robotic cases were associated with an average excess hospital cost of $2,489 [26••]. Similarly, a cost analysis utilizing Finnish data found that the cost of robot-assisted hysterectomy is 1.5-3 times higher than that of other techniques [30]. The incremental cost of robot-assisted hysterectomy is related to increased cost of surgical equipment, maintenance, and longer operative time [31]. Of note, the excess cost attributable to robotics appears to have an inverse relationship with both surgeon and hospital volume of robotic surgery. Though the cost of robotics remained higher than laparoscopy in all scenarios modeled using national database information for laparoscopic or robot-assisted hysterectomy between 2006 and 2012, increasing hospital and surgeon procedure volume was found to decrease the cost differential [32].

Conclusion

Given the improved perioperative outcomes with minimally invasive approaches, abdominal hysterectomy should be reserved for patient scenarios where vaginal, laparoscopic or robotic surgery is not feasible. When deciding between the various minimally invasive approaches, one must take into account variation in cost by approach; vaginal hysterectomy is consistently less expensive than other modes. A limitation of the available literature is the small number of randomized or prospective studies comparing surgical approach to hysterectomy. Additionally, surgeon-specific and patient-specific issues cannot be overlooked when evaluating such complex decisions.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of outstanding importance

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005 with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans, Table 100. NCHS, Hyattsville, MD (2005)

Merrill RM, Layman AB, Oderda G, Asche C. Risk estimates of hysterectomy and selected conditions commonly treated with hysterectomy. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(3):253–60.

Suton C. Past, present, and future of hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(4):421–35.

Baskett TF. Hysterectomy: evolution and trends. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19(3):295–305.

Semm K. Hysterectomy via laparotomy or pelviscopy. A new CASH method without colpotomy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1991;51(12):996–1003.

Reich H, de Cripo J, McGlynn F. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg. 1989;5:213–5.

Diaz-Arrastia C, Jurnalov C, Gomez G, Townsend Jr C. Laparoscopic hysterectomy using a computer enhanced surgical robot. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1271–3.

Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, Lu YS, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):233–41. This article provides an interesting look at hysterectomy trends between 1998 and 2010. Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the authors extrapolated annual hysterectomy volume in the United States and reported a decline in hysterectomy volume over time to a nadir of 433,621 cases in 2010.

Cohen SL, Vitonis AF, Einarsson JI. Updated hysterectomy surveillance. JSLS. 2014; in press.

Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, Burke WM, Lu YS, Neugut AI, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA. 2013;309(7):689–98.

Lee J, Jennings K, Borahay MA, Rodriguez AM, Kilic GS, Snyder RR, Patel PR. Trends in the national distribution of laparoscopic hysterectomies from 2003-2010. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014.

Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucheri E, Zurawin R, Einarsson JI. Trends in Reported Resident Surgical Experience in Hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014; in press.

Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (3): CD003677.

Mäkinen J, Brummer T, Jalkanen J, Heikkinen AM, Fraser J, Tomás E, et al. Ten years of progress–improved hysterectomy outcomes in Finland 1996–2006: a longitudinal observation study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10):e003169.

Mamik MM, Antosh D, White DE, Myers EM, Abernethy M, Rahimi S, Bhatia N, Qualls CR, Dunivan G, Rogers RG. Risk factors for lower urinary tract injury at the time of hysterectomy for benign reasons. Int Urogynecol J. 2014.

ACOG Committee Opinion. No. 444: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156–8.

AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):1–3.

Silasi DA, Gallo T, Silasi M, Menderes G, Azodi M. Robotic versus abdominal hysterectomy for very large uteri. JSLS. 2013;17(3):400–6.

Sesti F, Cosi V, Calonzi F, Ruggeri V, Pietropolli A, Di Francesco L, Piccione E. Randomized comparison of total laparoscopic, laparoscopically assisted vaginal and vaginal hysterectomies for myomatous uteri. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014.

Bogani G, Cromi A, Uccella S, Serati M, Casarin J, Pinelli C, Lazzarini C, Ghezzi F. Laparoscopic versus vaginal hysterectomy for benign indications in women aged 65 years or older: propensity-matched analysis. Menopause. 2014.

Carbonnel M, Abbou H, N'guyen HT, Roy S, Hamdi G, Jnifen A, et al. Robotically assisted hysterectomy versus vaginal hysterectomy for benign disease: a prospective study. Minim Invasive Surg. 2013;2013:429105.

Paraiso MF, Ridgeway B, Park AJ, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Falcone T, et al. A randomized trial comparing conventional and robotically assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(5):368.e1–7.

Sarlos D, Kots L, Stevanovic N, von Felten S, Schär G. Robotic compared with conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):604–11. This study is a randomized trial of 100 patients who were assigned to either robotic or conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy. The authors report comparable perioperative outcomes but longer operative time with robotic cases.

Patzkowsky KE, As-Sanie S, Smorgick N, Song AH, Advincula AP. Perioperative outcomes of robotic versus laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. JSLS. 2013;17(1):100–6.

Martino MA, Berger EA, McFetridge JT, Shubella J, Gosciniak G, Wejkszner T, et al. A comparison of quality outcome measures in patients having a hysterectomy for benign disease: robotic vs. non-robotic approaches. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):389–93.

Rosero EB, Kho KA, Joshi GP, Giesecke M, Schaffer JI. Comparison of robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):778–86. The authors utilized data from the 2009 and 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample to demonstrate differences between robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy. They found that hospital costs were on average $2,489 greater with robotic procedures.

Woelk JL, Borah BJ, Trabuco EC, Heien HC, Gebhart JB. Cost differences among robotic, vaginal, and abdominal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):255–62. This study provides an in-depth look at all-cause costs associated with varying modes of hysterectomy, including the cost of readmissions and complications. They demonstrated the lower cost with vaginal hysterectomy, and similar costs with robotic or abdominal hysterectomy.

Dayaratna S, Goldberg J, Harrington C, Leiby BE, McNeil JM. Hospital costs of total vaginal hysterectomy compared with other minimally invasive hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):120.e1–6.

Cho HY, Park ST, Kim HB, Kang SW, Park SH. Surgical outcome and cost comparison between total vaginal hysterectomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy for uteri weighing >500 g. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(1):115–9.

Tapper AM, Hannola M, Zeitlin R, Isojärvi J, Sintonen H, Ikonen TS. A systematic review and cost analysis of robot-assisted hysterectomy in malignant and benign conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:1–10.

Teljeur C, O'Neill M, Moran P, Harrington P, Flattery M, Murphy L, Ryan M. Economic evaluation of robot-assisted hysterectomy: a cost-minimisation analysis. BJOG. 2014.

Wright JD, Ananth CV, Tergas AI, Herzog TJ, Burke WM, Lewin SN, et al. An economic analysis of robotically assisted hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1038–48.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Sarah L. Cohen and Dr. Jon I. Einarsson each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, S.L., Einarsson, J.I. The Outcomes and Cost of Hysterectomy: Comparing Abdominal, Vaginal, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Approaches. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 3, 277–280 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-014-0098-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-014-0098-3