Abstract

In recent years, the number of people who identify as “spiritual but not religious” has grown. At the same time, many addiction recovery programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous promote spiritual beliefs to help those suffering from alcohol use disorders. In this paper, we hypothesize and test to see whether individuals who have attended substance abuse groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous are more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious (SBNR). Using longitudinal data from the Midlife Development in the United States study (N = 1711), we find that those who have attended substance abuse groups are more likely to identify as SBNR. Further, frequency of attendance in these groups is positively and significantly associated with being SBNR when compared to being both religious and spiritual. Implications for understanding the connections among religion, spirituality, and substance abuse recovery programs are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In November 2016, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a 428-page report entitled “Facing Addiction in America.” Alarmingly, the report states that 20.8 million people (7.8% of the U.S. population) fit the criteria for having a substance use disorder, though only 2.2 million individuals received treatment in 2015 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). Of those who did seek help, however, mutual aid programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.), Narcotics Anonymous (N.A.), or other programs that follow a 12-Step model were the most widely used for recovery from substance abuse (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). While these groups do not provide medical treatment, many researchers, including the Surgeon General, recognize their prevalence and recommend recovery support services such as A.A. to help individuals overcome substance abuse and addiction (Kaskutas 2009; Kelly et al. 2009).

Concurrently, recent years have also seen a steady increase in the population of those who identify as spiritual but not religious (SBNR). The increasing frequency of this expression has caught the attention of sociologists and religion scholars who wish to understand this phenomenon (Hastings 2016). While those who identify as SBNR are a growing minority in the United States (Chaves 2011), the spread of “post-Christian spirituality” has also expanded in other post-industrial nations (Houtman and Aupers 2007). By their own admission, SBNRs eschew organized religion and prefer instead self-directed approaches to spirituality (Besecke 2013; McClure 2017a; Mercadante 2014). In fact, the very expression, “spiritual but not religious,” implies that some distinguish between spirituality and religion, even though the majority of people living in the U.S. identify as both religious and spiritual (Chaves 2011; Hill et al. 2000; Zinnbauer et al. 1997). Further, the SBNR expression is more than a mere semantic shift, for SBNRs have a distinct theological outlook that often runs contrary to traditional religious beliefs and practices (Fuller 2001; Huss 2014; Mercadante 2014). For instance, McClure (2017a) shows that SBNRs are more likely to view God as a Higher Power or “cosmic force” when compared to those who are both religious and spiritual, and SBNRs are more likely to reject the perceived moral authority of God or the Bible in favor of an individualistic code of ethics.

The reasons for examining the association between substance abuse group attendance and SBNR identification are many. First, studies show that religious and spiritual identifications have a wide range of discernible social outcomes, safeguarding health and well-being in some instances (Ellison et al. 2008), but also nurturing attitudes that are dangerous and sometimes criminal (Jang and Franzen 2013). Second, since most studies of religion have focused primarily on Western, organized, or monotheistic religious institutions (Edgell 2012), research into SBNRs and its correlates is an understudied area in the sociology of (lived) religion. Lastly, while hundreds of studies examine the connections between addiction and spirituality (Cook 2004), understandings of spirituality and its connection to addiction vary widely. Likewise, as Holt et al. (2006:524) attest, “the relationship between religion and alcohol is quite complex.” However, the fact that substance abuse recovery groups have previously been considered quasi-religious organizations means that participation in such groups may be linked to SBNR identity at the individual level (Rudy and Greil 1989).

This paper, therefore, aims to contribute to the sociology of religion and the sociology of health by linking SBNR identification with other life events that may be associated with an implicit SBNR mentality. We hypothesize and test to see whether adults who have attended substance abuse groups are more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious. This hypothesis rests on the examination of previous literature which claims that SBNR beliefs are institutionalized within select substance abuse groups that constitute a quasi-religious organization (Rudy and Greil 1989). Further, recent qualitative studies have suggested that A.A. participants are likely to identify with spiritual but not religious beliefs (McClure, forthcoming; Mercadante 2014).

Substance abuse groups, the most notable being A.A., have a long history of nurturing a self-directed approach to spirituality and submission to an undefined Higher Power. The rise of A.A. in the post-Prohibition era is considered here to be a primary institutional support system that nurtures an individualistic, spiritual orientation and eschews organized religious ties. Despite being founded less than 100 years ago, today A.A. claims over 2 million active members and 120,000 groups in approximately 175 countries worldwide (A.A. General Service Office 2017). Further, because participation in A.A. does not require members to adopt any one specific religious tradition exclusively, many substance abuse groups have an ideology that promotes belief in a Higher Power and which attendees believe may, in turn, help them overcome disease or addiction. Thus, this study aims to examine whether individuals who have attended substance abuse groups for alcohol or drug use disorders are more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious.

Background

The Rise of the Spiritual but not Religious

Although the expression “spiritual but not religious” has a distinctly modern ring, the beliefs and practices common among SBNRs go back over a century and surface among prominent psychologists (James [1902] 1999), poets (Emerson [1838] 2012; Whitman [1855] 2009), and figures in popular culture (Lennon [1971] 1998). Ideologically, SBNRs often situate themselves between the perceived extremes of those who profess dogmatic religious faith on the one hand and those who adopt a secular, humanistic outlook on the other (Huss 2014). For this reason, SBNRs often describe their worldview as one open to transcendence yet unconstrained by religious authorities (Besecke 2013; Houtman and Aupers 2007). These tendencies confound the usual sociological debates about the fate of the religious or secular landscapes in the United States. While some scholars argue that the main story of American religion is one of increasing competition and vibrant religiosity (Finke and Stark 2005), others point to the rise of the religiously unaffiliated as evidence that America is becoming more secular (Bruce 2002; Chaves 1994; Liu et al. 2012; Norris and Inglehart 2011; Yamane 1997). Regardless, large portions of the population do not neatly fit into purely religious or secular camps (Ammerman 2013; Berger 2014). As Fuller (2001) and Schmidt (2012) independently observe, the presence of those who prefer mystical or spiritual pursuits instead of either religious or secular worldviews is well documented. More recently, a number of scholars have shown that “diffuse spirituality” has grown (Chaves 2011:212), not only in the United States, but in many other Western nations as well (Heelas et al. 2005; Houtman and Aupers 2007).

Though theoretical and empirical progress has been made, part of the struggle in describing the religious, secular, or spiritual contours of any given landscape depends on the meaning and operationalization of terms (Smith 2017). Semantically, the expression “spiritual but not religious” implies a distinction between religion and spirituality. While SBNRs disavow formal religious ties and avoid dogmatic constraints, most Americans see no incompatibility between religion and spirituality, and as several researchers have discovered, a majority of Americans indicate that they are both religious and spiritual (Ammerman 2013; Hill et al. 2000; Marler and Hadaway 2002; Zinnbauer et al. 1997). More precisely, Chaves (2011) explains that approximately 80% of the American population identify as both, though the numbers of SBNRs nearly doubled among people under the age of 40 from 1998 to 2008. Today, estimates on SBNRs range from Fuller’s (2001) treatment on the subject (20%), to more recent surveys that place SBNRs at 27% of the overall population in the United States (McClure 2017a).

Despite the growth of SBNRs, researchers vary in their analyses and disagree as to what is behind SBNR identification. For instance, some scholars believe that the religiously unaffiliated are byproducts of aversion to conservative politics (Hout and Fischer 2002; Putnam and Campbell 2012). Though the religiously unaffiliated (or “nones”) are not to be confused with SBNRs, there is considerable overlap in their more liberal political attitudes (Besecke 2013).

Other researchers argue that SBNRs have become more prominent because of changes in the family or because of variations between birth cohorts. In their 35-year longitudinal study of over 3000 California families, Bengtson et al. (2013) find that younger birth cohorts are significantly less likely to view God as a transcendent Deity and prefer instead a theology marked by individual relationships, personal states of mind, and self-defined experiences. These trends map on well to previous studies that have examined the religious and spiritual constitutions of emerging adults, who are on the whole much less committed to religious orthodoxies and traditional institutions (Smith and Denton 2005; Wuthnow 2010). Further, when organized religion fails as a safeguard to protect families from divorce, individuals are perhaps less inclined to be religious. Zhai et al. (2008), for example, show that 62% of all SBNRs (in their sample) come from divorced parents. Theorizing as to why this may be, they write, “divorce may disrupt the intergenerational transmission of religious values and practices” and therefore “accentuate a personal ethos of self-reliance, increase distrust of organized religion, and enhance the appeal of a more individual, private spiritual life” (2008:380). Echoing these findings in a later study, Ellison et al. (2011) estimate that the relative odds of identifying as SBNR are 69% lower for young adults who come from intact, low-conflict families.

These observations support other research showing that the contours of American religion have been changing for some time. Beginning in the 1950s, many Americans began moving away from organized religious institutions and adopted their own individualized approaches to spirituality (Roof 2001; Wuthnow 1998). Though the rise of religious individualism is widely observed (Bellah et al. 1985; Madsen 2009), SBNRs should not be considered loners who lack social connections. As Hastings (2016) observes, SBNRs have similar levels of social connectedness when compared to those who regularly attend religious services. Further, the shift toward spiritual seeking is not unique to the American case either. Davie’s (2013) descriptive apothegm, “believing without belonging,” aptly describes the European religious landscape and explains how many SBNRs think of religion and spirituality in the United States too—that is, SBNRs have their own interior, spiritual lives and beliefs that exist apart from traditional religions (Bender 2010).

Despite the importance of geographical contexts, there is also evidence that SBNRs may be shaped by cultural forces that go beyond birth cohorts, changes in the family, or national boundaries. The fact that “post-Christian spirituality” is expanding in many Western nations (Houtman and Aupers 2007) should prompt researchers to investigate associations beyond birth cohorts and the family. For example, some research has argued that religious affiliation is associated with technological advances and that higher Internet usage coincides with a lack of religious affiliation, even when controlling for other important sociodemographic variables (Downey 2014; McClure 2017b). Perhaps, then, there are still other connections to SBNR identity that have yet to be discovered. In Mercadante’s (2014) small-scale qualitative study, over one-third of the SBNRs in her sample had attended some type of addiction recovery program. In sum, the well-attested, documented connections among religion, therapy, and spirituality thus provide a solid foundation from which to pursue this line of research further (Mercadante 1996; Miller 1998; Rieff 1968; Vaillant 2005).

Connections Between Substance Abuse Groups and Spirituality

The literature on addiction and spirituality frequently links religious and/or spiritual pursuits with overcoming negative health behaviors and addictions. In the case of A.A., individuals attempt to control or restrain their temptation to drink by following a specific 12-Step program. Of these steps, at least six make overt spiritual references to God or a “Power greater than ourselves” who can help bring those suffering from addiction into a state of sanity (AAWS [1939] 2001:32; see Table 1). Other spiritually-minded steps for recovery include admitting one’s powerlessness in the face of alcohol, seeking forgiveness from others, and (evangelistically) carrying this message of hope and recovery to others suffering from substance abuse.

With these observations in mind, scholars have explored the spiritual dimensions of addiction recovery programs. Historically, Peterson (1992:53) shows that “A.A. developed as a splinter group” from the Christian organization known as the Oxford Group and appropriated several of its techniques including its emphasis on personal confession, conversion, and continuation in the program (Peterson 1992; Walter 2009). As A.A. emerged in the post-Prohibition era, the leaders of A.A. retained many of the theological tenets of the Oxford Group while abandoning others to make the organization more inclusive and welcoming of Catholics and the non-religious.

The similarities between the Oxford Group and A.A. are so striking that some scholars believe A.A. should be considered a religious organization. Rudy and Greil (1989) reach this conclusion in their thorough review of A.A.’s structural and religious principles. As they and Mercadante (1996) independently explain, A.A. denies that it is a religious organization, but this denial is instrumental in helping it realize its therapeutic goals. Since the focus is therapeutic and not initially ideological, members can concentrate on those tasks that are not ideologically or religiously charged. Paradoxically, then, A.A. and many derivative addiction recovery programs disavow formal religious ties in order to reach a broader audience, but at the same time they rely heavily on spiritual ideas which are inclusive and intended to help members combat addiction. Over time, initiates address their substance use disorder through participation in “an unapologetically spiritual program” (Miller 2013:1258) that maintains a “spiritual but not religious” worldview (Mercadante 1996, 2014; Rudy and Greil 1989:46). The adoption of this worldview, in turn, is part of a broader process that requires greater participation with the organization. Particular to A.A. is the requirement of a sequencing of events not unlike spiritual conversion (Lofland and Stark 1965; Snow and Machalek 1984).

Recognizing the merits of Lofland and Stark’s model of conversion (1965), Greil and Rudy (1983) outline a four-stage model which involves intensified commitment to the program through behavioral, social, and eventually ideological conformity. Over time, most A.A. groups expect members to increase their participation, thereby eliminating other social groups that demand time and attention. Like other religious groups, A.A. and similar 12-Step programs ask members to give their time and effort to accomplish the goals of the group. Though religious disaffiliation often coincides with worse health and well-being (Fenelon and Danielsen 2016), increased participation with local A.A. chapters not only inhibits substance abuse generally, but also leads to spiritual changes and possibly religious conversions for many A.A. members (McClure, forthcoming). These personal transformations are often described in the context of the Christian tradition, as Cook’s (2004) meta-analysis of 265 published books on addiction and spirituality shows. Thus, the parallels between A.A. and other religious or spiritual organizations is well-attested and confirmed by a number of researchers (Davidson 2002; Greil and Rudy 1983; Mercadante 1996; Miller 1998; Rudy and Greil 1987, 1989; Tonigan 2007; Woolverton 1983).

While modeled on certain spiritual principles, the 12-Step programs that bear the imprint of A.A. are not necessarily associated with religious beliefs or values. Of course, not all 12-Step programs are the same. Some are explicitly religious; others are spiritually focused. Still other programs such as Rational Recovery disavow the 12-Step model entirely in favor of secular approaches (Dodes and Dodes 2015; Peele et al. 2000). Notably, however, today A.A. commands millions of followers worldwide (A.A. General Service Office 2017), whereas Rational Recovery disbanded its mutual aid groups decades ago, thus making it difficult to assess the size of its following, potential extinction, or co-option from other secular recovery groups (Trimpey 2010). Even so, the purpose of A.A. is to help individuals tackle their addiction, though a latent function may be that the program favors spirituality at the expense of organized religious institutions. In other words, while many of the tenets and practices of A.A. appear religious on their surface, over the course of its history A.A. has tried to “steer a middle course, borrowing from both the theological and therapeutic worlds” (Mercadante 1996:39).

Theory and Hypotheses

With current research documenting how A.A. uses spiritual language to accomplish its goals (Dossett 2017; Kelly 2017; Kurtz and White 2015), this paper aims to test a theory of commitment to mutual aid programs that we believe are related to the spiritual but not religious typology. One useful theoretical framework to develop this argument comes from Rudy and Greil’s (1987) organizational concept of a “commitment funnel.” Following Becker (1960) and Kanter (1968), they explain that commitment is “a concept that lies at the interface between individual definitions and organizational demands; if an organization is to survive it must develop mechanisms which encourage organization members to define continued participation as rewarding” (Rudy and Greil 1987:45). For those who attend mutual aid programs like A.A., the process of overcoming addiction requires increased commitment to the organizational demands of the program.

In the progression of this “commitment funnel,” researchers note that organizations often deploy a range of behavioral, social, and ideological control mechanisms (Rudy and Greil 1987). With A.A., for example, initiates are first asked to consider the possibility that they have a physical and spiritual illness that cannot be remedied through sheer willpower (Mercadante 1996). For those who have hit “rock bottom,” the admission that one has a problem and needs external—perhaps supernatural—assistance is not overly demanding, even if it does affront one’s prior sense of autonomy and self-control. To make these demands more palatable, A.A. does not demand full cognitive assent in these early stages. All that is asked for is behavioral conformity and for initiates to avoid using alcohol one day at a time. Next, the social dimension of regularly attending group meetings provides initiates with a sense of community and fellowship. Gradually, A.A. adherents deploy other behavioral techniques, such as constructing a moral inventory of their character defects and making amends with those they have harmed. Finally, through “prayer and meditation,” A.A. followers seek “conscious contact with God” and try to “carry this message to [other] alcoholics” (Table 1). In the process, A.A. programs often disavow theological notions of sin and salvation, preferring instead therapeutic doctrines of addiction and treatment (Mercadante 1996). These varying emphases not only reveal significant differences between religious organizations and addiction recovery programs, but they also highlight an ideological component which transpires as initiates graduate to more advanced steps in their commitment to the program. Thus, A.A. and derivative programs effectively funnel their members into an increasingly spiritual (but not necessarily religious) orientation and a new way of understanding reality.

Guided by this theory, our research aims to examine whether there is an association between attendance at substance abuse groups and identifying as spiritual but not religious. While previous studies have found religion to be a protective factor against substance abuse (Ellison et al. 2008; Holt et al. 2006; Michalak et al. 2007), no quantitative study to our knowledge has investigated the association between spiritual and religious identities and attending substance abuse groups. Using data from the Midlife Development in the United States survey, we specify the following hypotheses:

- H1:

-

Individuals who have ever attended substance abuse groups are more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious.

- H2:

-

Individuals who have attended substance abuse groups more frequently are more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious.

Data and Methods

Sample

This study draws on two waves of data from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS; Brim et al. 2004). Wave 1 data for the MIDUS were collected between 1995 and 1996 by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. The investigators used random-digit dialing to obtain a sample of non-institutionalized, English-speaking adults ages 25–74 in the contiguous United States. The sample respondents were first administered a telephone interview which yielded a 70% response rate. Those who completed the telephone interview were then mailed a self-administered questionnaire (87% response rate). The overall response rate at Wave 1 was 61% (0.70 × 0.87 = 0.61) or 3034 respondents who completed both the telephone interview and the mailed questionnaire. The respondents were contacted again about 10 years later in 2004–2006. Of the 3034 respondents who were surveyed at Wave 1, 1748 respondents completed both the telephone interview and the mailed questionnaire at Wave 2. The sample for this analysis was limited to respondents who had a valid score on the dependent variable and a valid sample weight, resulting in a final sample size of 1711.

Measures

Dependent Variable

We use two ordinal measures collected at Wave 2 to capture the religious and spiritual identities of respondents: “how religious are you?” and “how spiritual are you?” We recoded each measure into a dichotomous indicator, coded 1 for responses of somewhat or very, and coded 0 for responses of not at all or not very. Comparing responses across both variables, we created a four-category typology: (1) neither religious nor spiritual, (2) religious but not spiritual, (3) spiritual but not religious, and (4) both religious and spiritual. For example, a respondent who reported being not at all or not very religious, but somewhat or very spiritual would be categorized as “spiritual but not religious.” In preliminary analyses, we tested alternative coding strategies (e.g., very versus otherwise), but the substantive conclusions were the same (Table 2).

Key Independent Variables

We draw on two distinct, but related measures from Wave 1 in examining engagement in substance abuse groups. First, respondents were asked whether they have ever attended “groups for people with substance problems such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Rational Recovery.” The variable ever attend is coded 1 if the respondent attended a meeting at least once in his or her lifetime and 0 otherwise. Second, respondents were asked how many times they have attended meetings in the past 12 months. The measure for number of times attended is a count variable ranging from 0 to 200 among our sample respondents. Both questions were asked on the mailed questionnaire, which helps to reduce social desirability bias.

Control Variables

We include an array of covariates collected at Wave 1 that may potentially confound the relationship between substance abuse group attendance and religious/spiritual identities in the analysis. Chronological age is measured in years. Female is a binary variable coded 1 for female and 0 for male. Non-white is a binary variable coded 1 for non-white respondents and coded 0 for white respondents. Education is a continuous variable that ranges from 1 (no school/some grade school) to 12 (PhD, MD, JD, or other professional degree). Household income in the past 12 months is measured in thousands and top-coded by the data investigators at $300,000. Current marital status distinguishes between respondents who are married, divorced/separated, widowed, and never married (reference group). We also adjust for whether the respondent has any children under age 18 (1 = yes, 0 = no). Religious affiliation is measured using a series of binary variables: evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant, Catholic, other religious preference, and no religious preference (reference group). Because religiously affiliated individuals are less likely to experience substance abuse problems in the first place, religious affiliation can also influence substance abuse and is included in our analysis.

In addition to sociodemographic characteristics, we also account for early-life conditions including childhood religiosity, rural residential upbringing, and parental divorce before age 16. Childhood religiosity is derived from the question, “How important was religion in your home when you were growing up?” The response categories ranged from 1 (not very important) to 4 (very important). The variable pertaining to a rural residential upbringing is a binary indicator coded 1 for respondents who were raised in a rural area for most of their childhood and coded 0 otherwise. Parental divorce is also a binary variable coded 1 for parental divorce or separation before age 16 and 0 otherwise.

Table 3 provides the range, mean, and standard deviation for all study covariates.

Analytic Plan

We performed the analysis for this study in two stages using multinomial logistic regression in Stata 15.0. First, we estimated the associations between each of the substance abuse group variables (ever attend and number of times attended) and religious and spiritual identities. Model 1 allows us to assess the association between any involvement in a substance abuse group and religious and spiritual identities, whereas Model 2 takes a more nuanced approach—capturing not only past involvement, but also degree of exposure or involvement in addiction recovery groups. We found that there is considerable variability among those who have attended group meetings—with some respondents who are highly engaged and others not at all. Indeed, more than half of these respondents (57%) have not attended self-help groups in the past 12 months.

In the second stage of the analysis, we compared ever attend and number of times attended by simultaneously estimating their associations with the religious/spiritual typology in Model 3. These variables were only moderately correlated (r = 0.43) and collinearity diagnostics revealed low variance inflation factors (VIF) for the model (mean VIF < 2). If both variables are significant in the final model, then having ever attended—even if not recently—is associated with religious and spiritual identities, and more frequent attendance has an association above and beyond a minimum one-time attendance. While it is indeed possible that individuals with a religious and spiritual identity begin addiction recovery programs and then drop out when the program demands full cognitive assent, we control for religiosity in childhood, prior to attendance at substance abuse groups. These models cannot make causal assertions but rather point to possible associations between being SBNR and attendance in addiction recovery programs. Likewise, if only frequency of attendance is significant, this will reveal an important relationship between engagement in substance abuse groups and religious and spiritual identities.

The amount of missing data on the study covariates was small with less than two percent of respondents missing on more than one variable. Ever attend had the most amount of missing data on a single variable (2.5%), followed by household income (1.7%). We thus used listwise deletion for the analysis; in supplementary analyses, we performed the analysis using multiple imputation and our conclusions were the same. In all regression models, we applied sample weights that adjust for differences in both the probability of being selected into the sample and nonresponse.

Results

The majority of respondents reported being both religious and spiritual (66%) followed by spiritual but not religious (17%). The fewest number of respondents reported being religious but not spiritual (5%), while another 12% reported being neither religious nor spiritual. About 6% of the respondents in our sample have attended a substance abuse group at least once in their lifetime. The mean number of times respondents reported attending meetings in the past year was 1.865 with a standard deviation of 15.897; the median score among attendees was 50 (or about once a week).

The respondents ranged in age from 20 to 74 with the average respondent being 48 years of age. The sample was predominately white with 55% being female and the average respondent attending at least some college (approximately one-third of respondents earned a four-year college degree or more). Most respondents were married at baseline (68%), and 38% had a child under the age of 18 living at home. On average, respondents reported that religion was between “somewhat important” and “very important” in the household in which they were raised, and the majority of respondents reported a current religious affiliation (90%).

Table 4 presents results from the multinomial logistic regression equations. The comparison group for all models is “both religious and spiritual.” Due to the small number of respondents in the “religious but not spiritual” category, we excluded these individuals from further analysis to avoid perfect collinearity with other regressors in the model. Model 1 reveals that those who have ever attended a substance abuse group are two to three times (relative risk ratio [RRR] = 2.655) as likely to report being spiritual but not religious at Wave 2 compared to being both religious and spiritual. Moreover, those who reported any religious preference (compared to no religious preference) were less likely to identify as SBNR, as were those raised in a household in which religion was important. In addition, being older, female, and living in a rural area as a child were all associated with decreased risk of being spiritual but not religious. More educated and higher-income respondents had an increased risk of identifying as SBNR compared to those who identify as both religious and spiritual.

By contrast, having ever attended a substance abuse group was not significantly related to being neither religious nor spiritual. Compared to being both religious and spiritual, these adults were more likely to be male and have higher income. In addition, being raised in a household in which religion was important and reporting a current religious affiliation were both negatively related to being neither religious nor spiritual.

Model 2 in Table 4 substitutes the variable ever attend for number of times attended in the past year. Similar to the previous model, higher attendance at group meetings is significantly and positively associated with being spiritual but not religious (RRR = 1.018) compared to being both religious and spiritual. Once again, frequency of attendance is not significantly associated with identifying as neither religious nor spiritual compared to being both religious and spiritual. The pattern of results for the remaining covariates is unchanged from Model 1.

Model 3 in Table 4 brings both substance abuse group variables into the same model. When both variables are estimated together, the association with having ever attended a meeting is rendered non-significant. However, frequency of attendance in the past year remains positively and significantly associated with identifying as SBNR (RRR = 1.015) compared to being both religious and spiritual. Similar to results from the previous model, frequency of attendance is not significantly associated with being neither religious nor spiritual. The pattern of results for the remaining covariates is similar to the previous models.

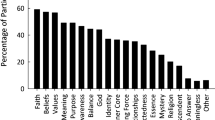

In supplementary analyses, we differentiated between low- and high-frequency attenders to illustrate further the importance of engagement in these groups. Because the variable measuring frequency of attendance was skewed, we coded scores below the median as low attendance, whereas high attendance was equal to scores at or above the median (50 on a scale of 0–200). We then grouped respondents into four categories (1 = never attended; 2 = attended at least once but not in the past year; 3 = low attendance in the past year; 4 = high attendance in the past year) and used the margins command in Stata to compute average adjusted predictions. Figure 1 displays the predicted probabilities of being SBNR according to each group. The results reveal that the predicted probability of identifying as SBNR for those who have never attended (17%) is not significantly different from those who have attended a meeting at least once but not in the past year (24%) or had low attendance (22%) in the past year. However, the predicted probability of being SBNR among respondents who reported high attendance in the past year was 62%—significantly greater than all other groups at p < 0.01.

We also examined respondents in the “religious but not spiritual” group using the data at Wave 1, which more than doubled the number of individuals in this category (n = 213). Based on the cross-sectional data, the pattern of results was similar to those shown for the “neither religious nor spiritual” group in Table 4: both ever attending a substance abuse group and frequency of attendance were non-significant for those who identified as religious but not spiritual when compared to being both religious and spiritual.

Discussion

According to the U.S. Surgeon General, in 2014 over 43,000 people in the United States died of drug overdoses while 88,000 deaths came as a result of alcohol misuse (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). In addition to the social turmoil that drug and alcohol use disorders generate for individuals, families, and communities, the negative economic impact of these events is staggering and estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2016). In light of these issues, professionals across the medical, therapeutic, and religious fields have proposed various types of treatment. Since the 1930s, Alcoholics Anonymous and similar 12-Step programs have offered a programmatic alternative to the problems typically associated with addiction, and today A.A. claims over 2 million active members and 120,000 groups in roughly 175 countries worldwide (A.A. General Service Office 2017). Though researchers have explored the efficacy of such programs with mixed results, much less is understood about the individual-level religious and spiritual identities associated with such programs.

Our research shows that individuals who attend substance abuse groups are significantly more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious when compared to being both religious and spiritual. Even though most Americans report being both religious and spiritual, respondents in this study who at some point in their lives attended an addiction recovery program were two to three times more likely to report being SBNR as compared to being religious and spiritual; however, when considered simultaneously, only frequency of attendance in these groups was significantly associated with being SBNR. Further, attending recovery groups had no apparent association with other spiritual and religious identities such as being neither religious nor spiritual. These findings are significant not only because they point to an association between spirituality and substance abuse programs that often goes overlooked, but also because they potentially give insight into how some individuals come to identify as SBNR in the first place.

To date, one of the few explanations that attempts to account for the growing presence of SBNRs comes from Zhai et al. (2008), who find that parental divorce predicts SBNR self-identification. Our research builds on these findings and suggests that addiction recovery groups are also associated with the presence of SBNRs in America’s modern religious landscape. Moreover, our research helps support and further specify Hasting’s (2016) finding that SBNRs have comparable levels of social connectedness when compared to religious service attenders. Indeed, one can imagine that individuals who regularly attend group meetings would score well on levels of social connectedness. For sociologists of religion and health, however, what has gone largely unnoticed is that individuals who attend recovery groups for substance abuse may also be more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious in their continued efforts to overcome addiction. For those in the professional religious guild, too, referring laity with substance use disorders to programs that can help them achieve sobriety may be good practical counsel but also introduce some ideas that run counter to their congregation’s established religious orthodoxy.

As with other projects of this nature, some limitations exist which deserve mention. First, while the primary independent variables used in this study explicitly mention Alcoholics Anonymous, they also include other less widespread substance abuse programs such as Rational Recovery which deploy techniques and strategies different from those used in A.A. or other 12-Step programs. Though A.A. remains the most popular mutual aid program for recovery from substance use disorders, it would be profitable to know more precisely whether attending substance abuse programs in general (rather than certain programs in particular) has discernible religious/spiritual correlations. Second, because of the personal stigma associated with substance abuse, our findings may underestimate the prevalence of group attendance and thus reflect more conservative estimates. Third, the retrospective data used in this study may have the potential for recall bias since some respondents may have forgotten whether they ever attended a self-help group for people with substance problems. Notably, however, we reached the same conclusions when we used the more proximate measure of attendance in the past 12 months. Finally, individuals who are more spiritual and less religious may be more likely to attend addiction recovery groups in the first place and stay involved in these groups given their spiritual underpinnings. This issue needs to be examined more fully in future research.

With these findings in view, future researchers may wish to reproduce this study using other survey data or conduct qualitative work that confirms or challenges our conclusions. We encourage such research avenues while recognizing the difficulties that will inevitably surface. Few surveys, for example, ask respondents questions about their religious and spiritual identities and their attendance at substance abuse groups. The MIDUS survey is therefore particularly well-suited for our analyses and consists of multiple waves, thus allowing us to examine whether substance abuse programs are associated with various religious and spiritual identities over time.

Given the current social, emotional, and economic costs of addiction in the United States and elsewhere, the 12-Step program of substance abuse recovery modeled by Alcoholics Anonymous will likely remain a popular program for those looking for solutions. Finding a path to greater health and sobriety—for individuals and families gripped by addiction or for the medical, legal, and religious professionals often enlisted to help—is a laudable goal. This paper sheds light on one of the unanticipated associations of attending substance abuse programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Though the efficacy of different treatment programs for drug and alcohol addiction continues to be hotly debated, we find evidence for both of our hypotheses. Namely, individuals who have ever attended addiction recovery programs such as A.A. are significantly more likely to identify as spiritual but not religious rather than identify as both religious and spiritual, and those who attend such programs more frequently have the greatest likelihood of identifying as spiritual but not religious.

References

A.A. General Service Office. 2017. “Estimated Worldwide A.A. Individual and Group Membership.” Retrieved October 19, 2018 (https://www.aa.org/assets/en_US/smf-132_en.pdf).

AAWS. [1939] 2001. Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women Have Recovered from Alcoholism, 4th ed. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services.

Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual but Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52 (2): 258–278.

Becker, Howard S. 1960. Notes on the Concept of Commitment. American Journal of Sociology 66 (1): 32–40.

Bellah, Robert, Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven M. Tipton. 1985. Habits of the Heart, 1st ed. New York: Perennial.

Bender, Courtney. 2010. The New Metaphysicals: Spirituality and the American Religious Imagination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bengtson, Vern L., Norella M. Putney, and Susan Harris. 2013. Families and Faith: How Religion Is Passed down across Generations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Berger, Peter L. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Besecke, Kelly. 2013. You Can’t Put God in a Box: Thoughtful Spirituality in a Rational Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brim, Orville Gilbert, Carol D. Ryff, and Ronald C. Kessler. 2004. How Healthy Are We? A National Study of Well-Being at Midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chaves, Mark. 1994. Secularization as Declining Religious Authority. Social Forces 72 (3): 749–774.

Chaves, Mark. 2011. American Religion: Contemporary Trends. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cook, Christopher C.H. 2004. Addiction and Spirituality. Addiction 99 (5): 539–551.

Davidson, Robin. 2002. The Oxford Group and Alcoholics Anonymous. Journal of Substance Use 7 (1): 3–5.

Davie, Grace. 2013. The Sociology of Religion: A Critical Agenda, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Dodes, Lance, and Zachary Dodes. 2015. The Sober Truth: Debunking the Bad Science Behind 12-Step Programs and the Rehab Industry. Boston: Beacon Press.

Dossett, Wendy. 2017. A Daily Reprieve Contingent on the Maintenance of Our Spiritual Condition. Addiction 112 (6): 942–943.

Downey, Allen B. 2014. “Religious Affiliation, Education and Internet Use.” Retrieved January 11, 2020 (http://arxiv.org/abs/1403.5534).

Edgell, Penny. 2012. A Cultural Sociology of Religion: New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1): 247–265.

Ellison, Christopher G., Jennifer B. Barrett, and Benjamin E. Moulton. 2008. Gender, Marital Status, and Alcohol Behavior: The Neglected Role of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47 (4): 660–677.

Ellison, Christopher G., Anthony B. Walker, Norval D. Glenn, and Elizabeth Marquardt. 2011. The Effects of Parental Marital Discord and Divorce on the Religious and Spiritual Lives of Young Adults. Social Science Research 40 (2): 538–551.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. [1838] 2012. The Divinity School Address. In The Annotated Emerson, ed. D. Mikics, 100–119. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Fenelon, Andrew, and Sabrina Danielsen. 2016. Leaving My Religion: Understanding the Relationship between Religious Disaffiliation, Health, and Well-Being. Social Science Research 57: 49–62.

Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. 2005. The Churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy, Revised ed. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Fuller, Robert C. 2001. Spiritual, but Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America, 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Greil, Arthur L., and David R. Rudy. 1983. Conversion to the World View of Alcoholics Anonymous: A Refinement of Conversion Theory. Qualitative Sociology 6 (1): 5–28.

Hastings, Orestes P. 2016. Not a Lonely Crowd? Social Connectedness, Religious Service Attendance, and the Spiritual but Not Religious. Social Science Research 57: 63–79.

Heelas, Paul, Linda Woodhead, Benjamin Seel, Bronislaw Szerszynski, and Karin Tusting. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality, 1st ed. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hill Peter, C., I.I. Kenneth Pargament, W. Ralph Hood, E. McCullough Michael, P. James Swyers, B. David Larson, and J. Brian Zinnbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30 (1): 51–77.

Holt, James B., Jacqueline W. Miller, Timothy S. Naimi, and Daniel Z. Sui. 2006. Religious Affiliation and Alcohol Consumption in the United States. Geographical Review 96 (4): 523–542.

Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2002. Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference: Politics and Generations. American Sociological Review 67 (2): 165.

Houtman, Dick, and Stef Aupers. 2007. The Spiritual Turn and the Decline of Tradition: The Spread of Post-Christian Spirituality in 14 Western Countries, 1981–2000. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46 (3): 305–320.

Huss, Boaz. 2014. Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and Its Challenge to the Religious and the Secular. Journal of Contemporary Religion 29 (1): 47–60.

James, William. [1902] 1999. The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Modern Library.

Joon, Jang Sung, and Aaron B. Franzen. 2013. Is Being ‘Spiritual’ Enough Without Being Religious? A Study of Violent and Property Crimes among Emerging Adults. Criminology 51 (3): 595.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. 1968. Commitment and Social Organization: A Study of Commitment Mechanisms in Utopian Communities. American Sociological Review 33 (4): 499–517.

Kaskutas, Lee Ann. 2009. Alcoholics Anonymous Effectiveness: Faith Meets Science. Journal of Addictive Diseases 28 (2): 145–157.

Kelly, John F. 2017. Is Alcoholics Anonymous Religious, Spiritual, Neither? Findings from 25 Years of Mechanisms of Behavior Change Research. Addiction 112 (6): 929–936.

Kelly, John F., Molly Magill, and Robert Lauren Stout. 2009. How Do People Recover from Alcohol Dependence? A Systematic Review of the Research on Mechanisms of Behavior Change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addiction Research & Theory 17 (3): 236–259.

Kurtz, Ernest, and William L. White. 2015. Recovery Spirituality. Religions 6 (1): 58–81.

Lennon, John. [1971] 1998. “Imagine.” In Lennon Legend: The Very Best of John Lennon. Capitol.

Liu, Joseph, Cary Funk, and Gregory A. Smith. 2012. “‘Nones’ on the Rise.” Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved April 30, 2014 (http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/).

Lofland, John, and Rodney Stark. 1965. Becoming a World-Saver: A Theory of Conversion to a Deviant Perspective. American Sociological Review 30 (6): 862–875.

Madsen, Richard. 2009. The Archipelago of Faith: Religious Individualism and Faith Community in America Today. American Journal of Sociology 114 (5): 1263–1301.

Marler, Penny Long, and C. Kirk Hadaway. 2002. ‘Being Religious’ or ‘Being Spiritual’ in America: A Zero-Sum Proposition? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41 (2): 289–300.

McClure, Paul K. 2017a. Something besides Monotheism: Sociotheological Boundary Work among the Spiritual, but Not Religious. Poetics 62: 53–65.

McClure, Paul K. 2017b. Tinkering with Technology and Religion in the Digital Age: The Effects of Internet Use on Religious Belief, Behavior, and Belonging. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56 (3): 481–497.

McClure, Paul K. Forthcoming. Recovering Theism: Three Biographical Case Studies in Alcoholics Anonymous. Implicit Religion.

Mercadante, Linda A. 1996. Victims & Sinners, 1st ed. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Mercadante, Linda A. 2014. Belief without Borders: Inside the Minds of the Spiritual but Not Religious. New York: Oxford University Press.

Michalak, Laurence, Karen Trocki, and Jason Bond. 2007. Religion and Alcohol in the U.S. National Alcohol Survey: How Important Is Religion for Abstention and Drinking? Drug and Alcohol Dependence 87 (2–3): 268–280.

Miller, William R. 1998. Researching the Spiritual Dimensions of Alcohol and Other Drug Problems. Addiction 93 (7): 979–990.

Miller, William R. 2013. Addiction and Spirituality. Substance Use and Misuse 48 (12): 1258–1259.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2011. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peele, Stanton, Charles Bufe, Archie Brodsky, and Thomas Horvath. 2000. Resisting 12-Step Coercion: How to Fight Forced Participation in AA, NA, or 12-Step Treatment, 1st ed. Tuscon: See Sharp Press.

Peterson Jr., John H. 1992. The International Origins of Alcoholics Anonymous. Contemporary Drug Problems 19: 53.

Putnam, Robert D., and David E. Campbell. 2012. American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rieff, Philip. 1968. The Triumph of the Therapeutic. 1st ed. Harper Torchbooks.

Roof, Wade Clark. 2001. Spiritual Marketplace: Baby Boomers and the Remaking of American Religion, Reprint ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rudy, David R., and Arthur L. Greil. 1987. Taking the Pledge: The Commitment Process in Alcoholics Anonymous. Sociological Focus 20 (1): 45–59.

Rudy, David R., and Arthur L. Greil. 1989. Is Alcoholics Anonymous a Religious Organization? Meditations on Marginality. Sociology of Religion 50 (1): 41–51.

Schmidt, Leigh. 2012. Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Smith, Christian. 2017. Religion: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Matters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Smith, Christian, and Melina Lundquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Snow, David A., and Richard Machalek. 1984. The Sociology of Conversion. Annual Review of Sociology 10: 167–190.

Tonigan Scott, J. 2007. Spirituality and Alcoholics Anonymous. Southern Medical Journal 100 (4): 437.

Trimpey, Jack. 2010. Rational Recovery. Retrieved January 11, 2020 from http://www.rational.org/index.php?id=51.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2016. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, D.C.

Vaillant, George E. 2005. Alcoholics Anonymous: Cult or Cure? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39 (6): 431–436.

Walter, H. A. 2009. Soul-Surgery: Some Thoughts on Incisive Personal Work. BiblioLife.

Whitman, Walt. 1855. 2009. Leaves of Grass: The Original, 1855th ed. Nashville: American Renaissance Books.

Woolverton, John F. 1983. Evangelical Protestantism and Alcoholism 1933–1962: Episcopalian Samuel Shoemaker, The Oxford Group and Alcoholics Anonymous. Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 52 (1): 53–65.

Wuthnow, Robert. 1998. After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wuthnow, Robert. 2010. After the Baby Boomers: How Twenty- and Thirty-Somethings Are Shaping the Future of American Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Yamane, David. 1997. Secularization on Trial. In Defense of a Neosecularization Paradigm. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36 (1): 109–122.

Zhai, Jiexia Elisa, Christopher G. Ellison, Charles E. Stokes, and Norval D. Glenn. 2008. ‘Spiritual, but Not Religious’: The Impact of Parental Divorce on the Religious and Spiritual Identities of Young Adults in the United States. Review of Religious Research 49 (4): 379–394.

Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda Cole, Mark S. Rye, Eric M. Butter, Timothy G. Belavich, Kathleen M. Hipp, Allie B. Scott, and Jill L. Kadar. 1997. Religion and Spirituality: Unfuzzying the Fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36 (4): 549–564.

Funding

No funding was required to complete this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McClure, P.K., Wilkinson, L.R. Attending Substance Abuse Groups and Identifying as Spiritual but not Religious. Rev Relig Res 62, 197–218 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-020-00405-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-020-00405-2