Abstract

This paper analyses the effect of natural resource wealth on sustainable economic development in the top 8 resource-abundant sub-Saharan African countries according to the World Bank Wealth of Nations 2018 over the period 1981–2017. The study incorporates public debt as an explanatory variable in our analysis, which is an extension of previous natural resource-growth estimations, to throw more light on how natural resource abundance and debt overhang simultaneously affect economic growth in resource-abundant sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. The NARDL bounds testing approach and asymmetric Granger causality tests are employed. Long-run asymmetric effect results show that an increase in natural resource rents significantly increases economic growth in Equatorial Guinea. However, an increase in natural resource rents in the Congo republic negatively affects economic growth, validating the resource curse hypothesis. No significant effect was found in other countries studied. In terms of asymmetric causality results, no bidirectional causality between natural resource rents and economic growth was noted. We, however, identified a weak unidirectional asymmetric causality relationship running from economic growth to resource rents in the Congo Republic and natural resource rents to economic growth in South Africa. The study, therefore, suggests the implementation of efficient public debt management policies and an improvement in the quality of institutions for effective management of public loans and resource revenues to stimulate economic development in these resource-rich countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, natural resources, both renewable and nonrenewable, and ecosystem services are a part of the physical wealth of nations. Other forms of capital are derived from natural capital. They contribute towards fiscal revenue, income, and poverty reduction (OECD 2011). Sub-Saharan African nations continue to be home to a significant quantity of the world’s natural resource deposits despite centuries of mineral exploration on the continent. Although some sub-Saharan countries have been performing relatively well economically in recent years, most are still mired in abject poverty. The continent is a classic case of a wealthy beggar that mostly relies on external aid, loans, and grants for survival instead of its national wealth. Political leaders are often blamed for their rent-seeking behaviors and economic mismanagement, which accounts for the poor economic performance of the continent over the years. Other factors include political conflicts, high import dependency, relatively low level of education by citizens, unrestrained population growth rates, among others (Janda and Quarshie 2017). However, two main reasons identified by (Carmignani and Chowdhury 2010) for the stagnant growth in Africa are the curse of natural resources and the continent’s lack of significant growth drivers such as productive human capital, international trade openness, and public infrastructure.

Empirical studies after pioneering works by Gelb (1988); R. M. Auty and Auty (1990); R. Auty and Warhurst (1993); J. D. Sachs and Warner (1995); and Karl (1997) support natural resource abundance does not spur economic development in most mineral-rich countries mostly mineral-rich sub-Saharan African countries. Few success stories of resources being a blessing reported, for instance, in countries such as Botswana (Stevens and Olsen 2004; McFerson 2009). A negative relationship exists between natural resource abundance and democratic regimes in Africa (Wantchekon 2004). Studies that have confirmed the resource curse hypothesis identified weak institutions, poor governance, corruption, deteriorating terms of trade, conflicts, and debt overhang as channels through which natural resources adversely affect economic growth, especially in mineral-rich African countries (Mehlum et al. 2006a; Gylfason and Zoega 2006; Papyrakis and Gerlagh 2006; Iimi 2007; Kolstad and Wiig 2008; Tsani 2013; Sovacool and Andrews 2015; Öge 2016; Kasekende et al. 2016). In their studies, Havranek et al. (2016) research established that about 40% of empirical papers reported a negative effect, 20% a positive effect, and 40% finding no effect of natural resources on economic growth. A recent meta-analysis done on 69 empirical studies by Dauvin and Guerreiro (2017) provides favorable evidence supporting the time horizon hypothesis. They show that studies focusing on long-term relationships through cointegration estimations reported a higher negative effect of natural resources on growth compared to more shortsighted methodologies.

Empirical results from studies that have assessed the relationships between trade openness and economic growth are without a consensus. In their studies, Singh (2011); Keho (2017); and Khobai et al. (2018) reported that in the long run, a significant positive relationship exists between trade openness and economic growth. Similar findings were made by Rao and Jani (2009) and Sakyi (2011), who confirmed that trade openness positively affects economic growth in Fiji, Pakistan, and Ghana, respectively. According to Zahonogo (2017), up to a certain threshold, trade openness positively contributes to economic growth in sub-Saharan African countries, but beyond the threshold, growth declines in the long run. Karras (2003) examined the correlation between trade openness and economic growth between 1950 and 1992 in 56 economies. Results from the studies reveal real GDP per capita growth rate increases by 0.5%, with a 10% increase in trade openness, which confirms the positive impact of trade openness on economic growth.

Furthermore, external borrowing is considered an essential resource in the finance for development in the developing countries; however, in recent years, borrowing has become a critical economic problem not only for developing countries but for the developed countries (Doğan and Bilgili 2014). Mineral resource-rich governments tend to overspend on salaries, unproductive subsidies, and over-ambitious infrastructural projects. They also underspend on critical sectors such as health, education, and other social services. Therefore, governments usually over-borrow because they have improved creditworthiness when revenues from mineral resources are high. A decline in growth rates and growing external debt levels became apparent when most sub-Saharan African countries discovered mineral resources in commercial quantities for exports and generated significant resource rents as well (Janda and Quarshie 2017). It is widely known that natural resources serve as attractive collateral to obtain loans, especially from the international market. Therefore, predictably at the time where it became evident enough that countries in the sub-Saharan region, due to their resource endowment, their governments embarked on a borrowing spree. The loans are mostly not to invest in developments but to fund political parties, elections, and other extravagant expenditures. According to Teles and Mussolini (2014), public debt could have a more significant adverse effect on economic outcomes if it affects the productivity of government spending. Koffi (2019) explored the nonlinear relationship between public debt on economic growth in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries from 1960 to 2015. The study found that public debt enhances economic growth when its level is less than 36.18 percent threshold and threshold, an increase in public debt would lower economic growth. Resource-rich African countries are usually saddled with high external indebtedness. Yet, their management of resource endowment, a logical source of debt repayment, also remains a challenge, alongside their characteristic weak institutions.

Mamo (2012) assessed the impact of inflation on economic growth in 13 African countries from 1969 to 2009 using the correlation matrix, fixed effect, and panel granger causality tests. The study revealed inflation negatively affects economic growth in the study sample. In another study conducted by Eggoh and Khan (2014) for a sample of 102 countries for the period 1960–2009 using PSTR and dynamic GMM, they also reported a negative and nonlinear relationship between inflation and economic growth. In Kuwait, Saaed (2007) found a negative correlation between inflation and development, and similar findings were made by Ahmed and Mortaza (2005) in Bangladesh. Kasidi and Mwakanemela (2013) also confirmed a negative relationship between inflation and economic growth in Tanzania for the period 1990–2001 using the correlation matrix.

In contrast, Mallik and Chowdhury (2001) identified a positive relationship between inflation and economic growth after assessing Four Asian countries for 1970–2000 using cointegration tests and error correction model (ECM). Pollin and Zhu (2006) also found a positive correlation between up to 18% of inflation in a study of 80 countries for the period 1961–2000 using a nonlinear regression approach. Similarly, findings of the positive relationship below the threshold level were found in the work of López-Villavicencio and Mignon (2011). They studied the nexus between inflation and economic growth in 44 countries using the GMM method. According to Muzaffar and Junankar (2014), a positive correlation exists between inflation and growth at a threshold below 13% from a study conducted using a sample of 14 countries between 1961 and 2010. Manamperi (2014) found mixed results in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) after examining the link between inflation and economic growth from 1980 to 2012 using Johansen cointegration and ARDL. A positive relationship was identified in India and an adverse effect on others.

According to Cincotta and Engelman (1997), population growth hurts renewable and nonrenewable natural resources. They, however, noted that the negative effect is higher on renewable resources than on nonrenewable natural resources. Low population growth in high-income nations is likely to create social and economic problems. In contrast, high population growth in low-income countries may slow their development (Peterson 2017). Several researchers believe economic growth in high-income countries to be relatively slow as the years go by due to population growth in these countries (Baker et al. 2005). Other studies such as Mahmood and Linden (2017) are of the view that population growth will continue to pose a challenge as more people unavoidably use more of the limited resources available on earth, thus decreasing potential long-term growth. On the other hand, human beings can provide solutions to environmental constraints that hinder development; therefore, the more the population, the higher the chances of getting a country’s economic woes solved (Boserup 1990; Simon 1990). Recent studies have, however, shown that economic growth in developing countries is negatively affected by rapid population growth (Barro and Martin 2004; J. Sachs 2008; Headey and Hodge 2009).

Although most of the macroeconomic variables comprise nonlinear characteristics, however, the most significant part of the existing research on modeling the natural resource-growth nexus was performed in a linear structure that assumes a symmetric relationship, using different time series methodologies. Such linear assumptions could have been the reason for the mixed results found regarding the natural resource-growth relationship. Assuming the homogeneous panel of mineral-rich countries is considered, the natural resource endowment of each country and also its exploration capacities vary with time which therefore implies that the effect of resource rent on economic growth should be different. Furthermore, most of the standard approaches employed in previous studies, as noted, assumed that the impact of natural resources reported is constant over the period. This assumption is mainly unreliable because, in most cases, the minerals market, due to supply and demand uncertainties, experiences significant time fluctuations. That is why it is imperative to employ a methodology to deal with these nonlinearities. Using linear models might not be a suitable approach in examining the relationship between natural resource rents and economic growth, as it could offer misleading suggestions on such a relationship.

Moreover, as shown in a recent study by Ampofo et al. (2020), the response of GDP per capita to a positive change of total natural resource rents (increase) could be different than the reaction to negative change (decrease). As such, in this study, we also aim to examine further the possible asymmetric relationship between total natural resource rents and economic growth for eight mineral-rich countries in Africa based on the World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations 2018. They are Nigeria, South Africa, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Sudan, Zambia, Botswana, and the Republic of Congo.

This study, however, differs from previous studies by making the following contributions. First, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to examine the asymmetric relationship between natural resources and economic growth in the eight top natural resource-abundant countries in Africa using the NARDL model for the individual countries scenario (country-by-country). Thus, this econometric approach efficiently explains the asymmetric relationship between the variables because it incorporates short-run and long-run asymmetries. This method is an extension of the autoregressive distributed lags (ARDL) bounds testing approach (Pesaran et al. 2001) to allow for estimating asymmetric long-run and short-run coefficients. It also concurrently identifies asymmetries existing in the dynamic adjustment allowing regressors of mixed order I(0) and I(1). Second, the study incorporates public debt, inflation, and population. The choice and inclusion of these explanatory variables in our model, which extends previous nonlinear estimations, will throw more light on the transmission channels in establishing the relationship between natural resources and growth in Africa. It is also the first to empirically explore the simultaneous effect of natural resource abundance and excessive government borrowing in the study sample. We also employ Diks and Panchenko (2006) to determine the asymmetric causality direction in the relationship between natural resource wealth and growth in the study sample. Due to the limitation of small sample size and in cases, the information available for developing countries is annual. Therefore generating short time series of data, it is more appropriate to pool countries in a panel setting to overcome such limitation (Narayan and Narayan 2010).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: the next section presents a summary of the literature review regarding natural resources and economic growth. In the “Data and methodology” section, we provide the data sources and empirical methodology of the study. The “Data analysis and findings” section presents the empirical results. Conclusion and policy implication is outlined in the “Concluding remarks and policy implications” section.

Literature review

In this part, we briefly discuss the relevant literature that focuses on the nexus between natural resources and economic growth. Kronenberg (2004) showed that the prime reasons for the curse of natural resources among the transition economies were corruption and neglect of primary education. Mehlum et al. (2006b) also revealed that if institutions are of good quality, natural resources promote growth.

On the other hand, the existence of institutions favorable to predation activities contributes to transforming natural resources into a curse. From this perspective, there is a certain threshold from which the negative effect of natural resources is completely neutralized. Also, Gylfason and Zoega (2006) found that an abundance of natural resources has an indirect and positive impact on economic growth through human capital.

Some of the causes that can be ascribed to the occurrence of the natural resource curse are the Dutch disease; corruption and undermined political institutions; rent-seeking and conflicts; insufficient economic diversification, overconfidence, and loose economic policies; and debt overhang (Iimi 2007). SSA indeed seems to be the epitome of the resource curse syndrome. It is not all doom and gloom for the region. One practical example is that the resources themselves are not the problem and that it is the management of it. That is the problem in the case of Botswana. Botswana is a country that has a lot of resources and is also heavily dependent on resources.

According to McFerson (2009), 80% of Botswana’s exports come from primary resources (diamonds and other minerals). However, with good governance and sound resource management policies, Botswana boasts of a very sound economy, unlike the other SSA countries wallowing in abject poverty and conflict despite their resources. As asserted by Kolstad and Søreide (2009), deteriorating institutions are the development problem in mineral-rich countries instead of just one of the problems.

Ndikumana and Abderrahim (2010) attempted to establish the reason for the existence of this natural resource curse in Africa. They tried to determine if this occurrence is due to these countries’ lack of capacity to get adequate tax from the natural resource sector or their inability to expand their revenue base beyond the natural resource sector to the non-resource revenue avenues. They argue that countries with abundant resources in SSA have failed to make their resources count mainly because of two critical factors. First, they argue that, even though many SSA countries are endowed with abundant natural resources, these countries have failed to generate the actual revenue they deserve because of their inability to harness these resources. Ismail (2010) used data from 1977 to 2004 on various countries, mostly oil-exporting countries. He found out that permanent increases in the oil sector result in the contraction of the manufacturing sector, an increase in the price of labor to capital, and many more. Butkiewicz and Yanikkaya (2010) confirmed evidence of the resource curse using panel data for more than 100 developed and developing countries but did not find the same result based on cross-section data.

Frankel (2010) empirically tested the natural resource channels to show the negative relationship with economic growth. He used six variables as the main channels of the resource curse. These are world commodity prices in the long term, volatility, crowding out of manufacturing, civil war, weak institutions, and the Dutch disease. Bhattacharyya and Hodler (2010) analyzed panel data from 1980 to 2004 from 124 countries to study the correlation between natural resources and corruption and how the level of quality of institutions influences this relationship. They noted that resource rents increase the level of corruption within weak democratic institutional contexts and vice versa. They established that the relationship between corruption and resource rents is influenced by institutional quality. The Dutch disease is seen as one of the channels of the natural curse susceptibility, according to Klein (2010) and Frankel (2010).

However, Brown (2011) disagrees that the resource curse in SSA is independent of the type of resource. She argues that the resource curse is dependent on the type and variety of resources, arguing that countries with a smaller range of resources are likely to be more corrupt than those with a broader variety. Those with a broader variety of resources are likely to practice a more inclusive and cooperative system of governance to have access and benefits to these resources that might have been scattered at different parts of their country. Brown also categorized the causes of this natural resource curse into two groups. The first is economical, caused by the Dutch disease, and the second, she claims, is institutional problems.

Further argued that the colonial system of governance in African countries is one of the primary reasons behind the weak institutional infrastructure in the region. Brown also claims that the colonialism of Africa along ethnic and geographical lines left the continent heavily divided after the independence of most African countries. Even within the same colonized country, more attention was paid to where the colonial masters lived, which are the areas endowed with the resources. It is the reason behind the sharp contrast in the different living standards among people in the same country. A classic example is the case of post-apartheid South Africa. It also explains the high number of cases of a few influential elites against the majority unfortunate situation in most African countries.

Idemudia (2012) posited that Nigeria is often seen as a reference point for resource-rich developing countries suffering from the resource curse. Ackah-Baidoo (2012), however, explains that companies operating in Africa are under less pressure to comply with corporate social responsibility commitments due to weak institutions. Similarly, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) also explain that countries endowed with natural resources are characterized by weak political institutions that are counterproductive.

Thus, natural resources can destroy the quality of institutions through civil wars and institutional convulsions, which can weaken the state. Also, struggles for the capture and distribution of rent increases political instability and the risk of armed conflict (Carbonnier and Brugger 2013). According to them, leaders tend to redistribute extractive rents to influential groups more than proportionally to income growth to stay in power. Furthermore, Tsani (2013) examines the association between resource funds, governance, and institutional quality in resource-rich countries. He finds resource funds associated with the governance and institutional quality improvements as possible tools for addressing the resource curse. The study concluded that countries that have established resource funds perform well in terms of governance and quality of institutions. Torres et al. (2013) show that revenues generated by natural resources are primarily monopolized by the dominant political elite in the absence of good quality of institutions. Corrigan (2014) perceives the natural resource “curse” as a condition where the rewards made from resource usage are less than the total input cost. He assumes that natural resources negatively impact both economic development and governance in weak institutional countries. Badinger and Nindl (2014) noted that natural resources facilitate corruption.

Smith (2015) revealed that oil-rich countries show higher growth in income. The key argument advanced to explain the negative effect seems to be, besides the Dutch syndrome theory and the natural resource curse phenomenon, the poor quality of institutions. As noted by Jude and Levieuge (2017), weak institutions in less developed countries (LDCs), especially in SSA’s countries, are undoubtedly responsible for bad economic performances. They emphasized that slower productivity growth, lower investment, lower per capita income, and overall slower output growth are a result of lower institutional quality.

Ndjokou and Tsopmo (2017) reassessed the link between institutional quality, natural resource, and economic growth in 18 sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries using Gonzalez et al. (2017) for the period 1985–2013. The study confirmed the resource curse hypothesis by establishing a direct negative effect of a natural resource on economic growth in SSA countries. They, however, indicated that quality institutions form the basis for the relationship between natural resources and economic growth (Table 1).

Seda Yıldırım et al. (2020), in a related study to examine the association between natural resources and financial development in 16 developing countries, findings revealed that an increase in oil revenues has a positive effect on financial development in the long term. But, resource rents do not impact financial development in the short-term natural.

Also, Atil et al. (2020) in paper investigated the linkage between natural resources and financial development by considering oil prices, economic growth, and economic globalization in the case of Pakistan using long-run covariability for the period 1972–2017. They reported that natural resource abundance is positively linked with financial development.

Naseer et al. (2020) analyzed data from seven South Asian countries between 1990 and 2017. The findings confirm the presence of the resources curse hypothesis for South Asian countries. Li et al. (2020), in research, attempted to explore the effect of natural resources on financial development to determine the existence of a resource curse or resource blessing hypothesis in N-11 countries from 1990 to 2017. The Augmented Mean Group and Mean Group estimates were applied. Findings suggested a positive relationship between technological innovation and human capital with financial development. The study also confirmed the presence of the resource curse hypothesis indicated by the negative impact of natural resources on financial development.

Ampofo et al. (2020), in a study, investigated the asymmetric link between total natural resource rent and economic growth. The authors applied the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) developed by Shin et al. (2014) and Diks and Panchenko (2006) asymmetric Granger causality test in the case of top ten mineral-rich countries in the world for the period 1981–2015. They reveal that total natural resource rent hurts economic growth in Australia, DRC, and India. However, they found that natural resource rent positively affects economic growth in Brazil and Canada. They also reported asymmetric causality between natural resource rents and economic growth does not exist in the majority of the countries assessed.

Erdoğan et al. (2020) studied the role natural resources, globalization, human capital, and urbanization play in achieving environmental sustainability in resource-based economies using sub-Saharan countries as a case study. Their empirical findings showed that dependence and abundance of natural resources mount more pressure on the environment, therefore adversely affecting environmental sustainability. They reported similar results for urbanization, but in contrast, they found that globalization and human capital appear to be the key drivers for achieving a cleaner and sustainable environment in mineral-rich sub-Saharan countries.

Harris et al. (2020), in a paper, examined whether and the manner bureaucrats contribute to the resource curse in the New Oil States using Ghana and Uganda as case studies. They found that bureaucrats do not generally show attitudes that indicate contributing to the resource curse.

Ridena et al. (2021) employed the generalized method of moments (GMM) technique to test the presence of the natural resource curse in Indonesia and the role of financial development in mitigating it between 2012 and 2018. The results from the study show the presence of the natural resource curse in the country; however, they noted that financial development could mitigate the negative impact of natural resources on economic growth in Indonesia.

Hayat and Tahir (2021) examined the impact natural resource volatilities have on economic growth from 1970 to 2018 in three resource-rich countries. The authors applied the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) cointegration approach, and empirical results support a positive relationship between natural resources and economic growth in UAE and Saudi Arabia. Although they also found a positive link in Oman, the impact was statistically insignificant. In contrast, natural resource volatility was found to have a statistically significant negative on economic growth when the three economies were combined.

Aljarallah (2021) investigated the economic, social, and political effects of resource abundance in Kuwait, an oil-rich country applying the ARDL technique to data from 1984 to 2014. The cointegration results reveal that in the short-run, resource rents increase per capita GDP; however, in the long and short run, it adversely affects productivity, human capital, and institutional quality.

Entele (2021) assessed the role of institutions and ICT services in escaping the resource curse phenomenon using the fixed effect panel data approach. In the case of some groups of economies, resource abundance and indicators of institutional performance were found to have significant negative impacts on economic growth. However, the adoption of ICT services, the building of human capital, and quality institutions were reported to provide the basis to reverse the resource curse.

Saeed (2021) revisited the natural resource curse by investigating the association between natural resource dependence and per capita growth in panel data of 68 developing countries from 1994 to 2014. The empirical results confirmed the resource curse, and the phenomenon identified to be more prominent in oil-rich MENA countries.

Xie et al. (2021), in research, used panel data of 256 prefecture-level cities in China to examine the resource curse theory. Results from the regression analysis showed that, generally, natural resources contribute positively to economic development. However, the results varied at different thresholds in the case of 109 resource-based cities assessed.

Fagbemi and Kotey (2022) used the ARDL and VECM to assess the role natural resource rents play in the economy of Nigeria through the channel of institutional quality. Findings from the study confirmed that overdependence on natural resources could lead to a dysfunctional economic outcome in Nigeria. Furthermore, the study confirms that combining weak governance and natural resource rents could adversely impact the economy in both the long and short run.

Mlambo (2022), in another recent study, focused on analyzing the political aspects of the resource curse using the PMG-ARDL and the FMOLS on a panel data of selected African countries for the period 1995–2016. The results from the study showed that the efficient functioning of government positively affects resource rents. Also, a unidirectional causality running from efficient performance of government to resource rents was identified.

From the large volume of literature, it appears that the findings of empirical studies on the impact of natural resources on growth are mixed and non-conclusive. The majority of the studies carried out to establish the relationship between natural resources and economic growth was performed in a linear framework. However, some recent studies have explored the resource curse issue based on nonlinearity without examining the role of public debt. This research, therefore, further extends the current literature by providing further empirical evidence from eight top mineral-rich countries in sub-Saharan Africa, confirming the nonlinear relationship.

Data and methodology

Data sources

The data considered in this study are sourced from the World Development Indicator (WDI, 2018 – CD-ROM) and cover the period 1981–2017. The variables used are economic development (denoted by GDP per capita constant $2010) and total natural resource rents (sum of oil rents, natural gas rents, coal rents, mineral rents, and forest rents) expressed as a share of GDP. We also used four more explanatory variables: public debt, trade openness, inflation, and population growth. All the variables except inflation were transformed to natural logarithms to eliminate the problem of heteroscedasticity. For this study, resource-rich sub-Saharan African countries refer to the top 10 countries most endowed with natural resources per capita according to the World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations 2018. However, the countries chosen for this study and the timeframe were dictated by data availability. These are Nigeria, South Africa, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Sudan, Zambia, Botswana, and the Republic of Congo (Table 2).

Econometric methodology

Following the recent empirical work by Ampofo et al. (2020), it is possible to test the long-run relationship between natural resource rents and economic growth. The primary, extended model, therefore, takes the following functional form in Eq. (1) with all variables converted into logarithms except inflation before analysis:

The NARDL framework permits modeling asymmetric cointegration using positive and negative partial sum decompositions and identifying the nonlinear effects both in the short and long run. It also permits the joint investigation of the issues of non-stationarity and nonlinearity in the context of an unrestricted error correction model. The nonlinear cointegration regression (Shin et al. 2014) specified as:

where \({\beta }^{+}\) and \({\beta }^{-}\) are long-term parameters of \(kx1\) vector of regressors \({x}_{t}\), decomposed as:

where \({x}_{t}^{+}({x}_{t}^{-})\) are the partial sums of positive (negative) change in \({x}_{t}\) expressed as follows:

The NARDL (p, q) form of the Eq. (3), in the form of asymmetric error correction model (AECM), can be stated as:

where \({\theta }^{+}= - \rho {\beta }^{+}\) and \({\theta }^{-}= - \rho {\beta }^{-}\). In a nonlinear framework, the initial two steps to establish cointegration between the variables are similar to the linear ARDL bound testing method, i.e., estimating Eq. (6) using OLS and conducting the joint null (\(\rho ={\theta }^{+}= {\theta }^{-}=0\)) hypothesis test. However, in nonlinear ARDL, the Wald test is used to determine the long-run \({(\theta }^{+}= {\theta }^{-})\) and short-run (\({\pi }^{+}= {\pi }^{-}\)) asymmetries in the relationship. Lastly, the asymmetric cumulative dynamic multiplier effect of a unit change in \({x}_{t}^{+}\) and \({x}_{t}^{-}\) on \({y}_{t}\) is examined as follows:

whereas \(h\to \infty\), the \({m}_{h}^{+}\to {\beta }^{+}\) and \({m}_{h}^{-}\to {\beta }^{-}\). Recall that \({\beta }^{+}\) and \({\beta }^{-}\) are the asymmetric long-run coefficients and can be computed as \({\beta }^{+}=-{\theta }^{+}/\rho\) and \({\beta }^{-}=-{\theta }^{-}/\rho\), respectively.

In the framework of the asymmetric error correction model presented above, Shin et al. (2014) proposed two test statistics, namely the t-BDM and F-PSS, for testing the existence or absence of a cointegration relationship. While the t-BDM tests the null of no cointegration \(H0: \rho =0\) against the alternative hypothesis of cointegration \(H1: \rho <0\), the F-PSS tests the joint null of no cointegration \(H0: \rho ={\theta }^{+}={\theta }^{-}=0\) against the alternative joint hypothesis of cointegration \(H1: \rho ={\theta }^{+}={\theta }^{-}<0\). As the asymptotic distribution of the t-BDM and F-PSS statistics is non-standard regardless of whether the variables are I(0) or I(1), the conclusion for cointegration is taken by assessing two sets of critical values, one of which assumes that all variables are I(1). It provides a bound covering with all possible categorizations of the variables. If the calculated test statistics lie above the upper level of the bound, the \(H0\) is rejected, supporting cointegration. If the computed test statistics lie below the lower level of the bound, the \(H0\) cannot be rejected, indicating a lack of cointegration.

The asymmetric Diks-Panchenko causality test

In 1969, Granger proposed a causality test to define the dependence relations between economic time series. According to this, if two variables \(\{{X}_{t}\), \({Y}_{t}\), \(t\ge 1\}\) are strictly stationary, \(\{{Y}_{t}\}\) Granger causes \(\{{X}_{t}\}\) if past and current values of \(X\) contain additional information on future values of \(Y\).

Suppose that \({{\varvec{X}}}_{t}^{lx}=({X}_{t-1 X+1},\dots ,{X}_{t})\) and \({{\varvec{Y}}}_{t}^{ly}=({Y}_{t-1 y+1},\dots ,{Y}_{t})\) are the delay vectors—where \({l}_{X}\),\({l}_{Y}\ge 1\). (Diks and Panchenko 2006) examine the null hypothesis that past observations of \({{\varvec{X}}}_{t}^{lx}\) contain any additional information about \({Y}_{t+1}\) (beyond that in \({{\varvec{Y}}}_{t}^{ly}\)):

The following equation can represent the test statistic:

where \({f}_{X,Y,Z(x,y,z)}\) is the joint probability density function.

For \({l}_{X}={l}_{Y}=1\) and if \({\varepsilon }_{n}={Cn}^{-\beta }(C>\) 0, \(\frac{1}{4}<\beta <\frac{1}{3})\), Diks and Panchenko (2006) prove that the test statistic in Eq. (9) satisfies the following:

where \(\stackrel{D}{\to }\) denotes convergence in distribution and \({S}_{n}\) is an estimator of the asymptotic difference of \({T}_{n}(.)\) [(Fowowe 2016), (Bekiros and Diks 2008)].

Data analysis and findings

Descriptive statistics

The summary statics are presented in Table 3. This is important to derive the basic measure of central tendency and dispersion of the variables under study over the study period (1981–2017). Total natural resource rents, public debt, and trade openness are negatively skewed, while other variables of interest are positively skewed. The current research is conducted for a sample size panel of 296 observations with all series not normally distributed except public debt and trade openness, given the failure to reject the null hypothesis of normality. Also, we conducted a correlation matrix analysis to examine the relationship between the variables under consideration. The correlation between natural resource rents and trade openness and economic growth is positive. Public debt, inflation, and the population are negatively related to economic growth. Results, therefore, show natural resource rents and trade contribute positively to economic growth while public debt, inflation, and population growth negatively affect growth in the long run.

Unit root test

The next step is to examine the variable’s stationarity properties to ensure that none is integrated at order 2 or l(2). It is vital to perform this because the NARDL model of Shin et al. (2014) requires that the variables be integrated at order level or first difference to assess the cointegration between the variables. For this reason, we employ the augmented Dickey-Fuller (Dickey and Fuller 1979) based on the Schwarz information criterion and (Perron 1988) unit root tests, and the results are presented in Table 4. We, therefore, can conclude that the selected variables are stationer at I(1), so it is appropriate to estimate the NARDL model.

Johansen cointegration analysis

Table 5 presents the results of Maximum-Likelihood Johansen’s cointegration between total natural resource rents, economic growth, public debt, trade openness, inflation, and population growth. Since all of the parameters are significant at 5%, we confirm the presence of cointegration between variables. Although the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected, further tests to confirm possible nonlinearity are employed.

Linear Granger causality test

In Table 6, we report the results of the conventional linear Granger causality test. In the case of Botswana, we find a unidirectional causality relationship between total natural resource rent and economic growth, with causality running from total natural resource rents to economic growth. Furthermore, the total national resource rents do not Granger causes economic growth in the Republic of Congo, but economic growth Granger causes total natural resource rents. For the economy of Equatorial Guinea, we find a symmetric causality relationship from national resources to economic growth. However, we identified no causality running from economic growth to total natural resource rents. In Gabon, our results show a unidirectional linear Granger causality running from total natural resource rents and economic growth. Our results also confirm no Granger causality linkage between natural resource rents to economic growth in the Republic of Nigeria. In the South African economy, we note that economic growth causes natural resource rents, but no significant causality exists from natural resource rents to economic growth. Our findings from the linear Granger causality framework also show that in Sudan, a unidirectional Granger causality running from total natural resource rents to economic growth exists at a 10% level of statistical significance. Finally, in Zambia, the linear Granger causality results confirm natural resource rents cause economic growth but not vice versa.

The BDS test

To determine the possibility of nonlinear dependence between economic growth, resource rents, public debt, trade openness, inflation, and population, we employed the (Broock et al. 1996) BDS test applied on the residuals of the VAR(1) model for all variables. The BDS test is a nonparametric test, initially designed to test for independence and identical distribution (iid). The test hypothesis is as follows: H1: data not independently and identically distributed (i.i.d). As reported in Table 7, we reject the null of i.i.d residuals at various embedding dimensions (m); therefore, there is strong evidence at the highest level of significance against linearity.

Nonlinear ARDL bounds test

The NARDL bounds cointegration results are shown in Table 8. The t-statistic (\({T}_{BDM}\)) developed by Banerjee et al. (1998) confirms cointegration among variables in Equatorial Guinnea and South Africa at 5% and 10% significance levels, respectively. The NARDL F-statistic (\({F}_{PSS}\)) from Shin et al. (2014) validates the existence of asymmetric cointegration among the variables, which indicates that natural resource rents, public debt, trade openness, inflation, population, and economic growth have a long-run asymmetric association in the Botswana, Congo Republic, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, and South African economies.

Robustness check of the model (post-estimation)

We conducted robustness checks through the post-estimation technique of the NARDL model. Results, as shown in Table 9, indicate that the model did not suffer from serial correlation. Also, the Breusch and Pagan heteroscedasticity test findings infer a rejection of the chances of homoscedasticity and heteroscedasticity, which demonstrates that variance is constant in the data variables. Furthermore, the Ramsey RESET test is employed, and the results presented confirm models are stable and did not have misspecification errors or bias. Finally, the \({R}^{2}\) is an essential factor for the model validates; it is the best fit.

Asymmetric tests

Table 10 reports the estimated long-run coefficients associated with the positive and negative shocks in natural resource rents, trade openness, and economic growth.

Focusing on the estimated long-run coefficients of the asymmetric ARDL, we notice that total natural resource rent (NR +) positive shocks and (NR −) negative shocks insignificantly impact the economic growth of Botswana. These findings are a deviation from a previous study by McFerson (2009), who reported natural resources in Botswana significantly contribute to the country’s economic growth. The result is also inconsistent with research findings by Dineo (2019), who reported natural capital significantly contributes positively to economic growth in Botswana. Public debt and population growth have statistically significant (at conventional levels) negative impacts on growth. However, trade openness and inflation are positively linked to economic growth but statistically insignificant. Botswana, based on past literature, has been the reference for prudent management of mineral resource revenue in thus a case of resource blessing in sub-Saharan Africa. The negative effects of public debt and population growth could explain the insignificant impact of natural resources on economic growth outcomes in this study. The country heavily depends on its natural resources, as noted by McFerson (2009), 80% of Botswana’s exports come from a primary resource. Therefore, the country may be currently suffering from Dutch Disease, which may further explain why natural resources no more contribute significantly to the country’s economic growth.

In the long term, positive shocks to total natural resource rents in the Congo Republic significantly affect economic growth negatively (a coefficient of − 0.176). The relationship between a negative shock to total natural resource rent and economic growth is positive and statistically insignificant (a coefficient of 0.145). The results confirm evidence of the natural resource curse in the Congo Republic. It is consistent with findings reported by Ampofo et al. (2020), which revealed that an increase in natural resource rents in the Democratic Republic of Congo negatively affects the country’s economic growth. The country’s public debt has a significant adverse effect on economic growth. Trade openness, inflation, and population growth positively impact economic growth in the Congo Republic but are statistically insignificant at all conventional levels. Several years of political instability characterized by weak institutions and the negative impact of public debt on economic growth, as shown from the result, provide possible reasons for the resource curse in the Congo Republic.

In Gabon, as reported in Table 10, an increase in total natural resource rent positively affects economic growth but is statistically not significant in the long run. Negative shocks to natural resource rents, in contrast, positively impact economic growth, but the result is statistically not significant at usual levels of significance. It is consistent with findings made by Ampofo et al. (2020) in the case of Saudi Arabia. Also, Hayat and Tahir (2019) made similar findings in the case of Oman. We also find a statistically insignificant positive link between public debt and inflation to natural resources. Moreover, trade openness and population negatively affect economic growth but are not statistically significant. Gabon is among the few African countries not listed as heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) despite its mineral-rich status. It is, therefore, consistent with the positive impact of public debt on economic growth as per the results. However, not statistically significant results are contrary to the adverse effect of public debt on growth reported in most mineral-rich African countries.

Evidence from Equatorial Guinea shows that a positive shock to natural resource rents leads to a statistically significant positive effect (with a coefficient of 3.129) on economic growth. Consistent with our findings, Gylfason and Zoega (2006) posited that an abundance of natural resources has an indirect and positive impact on economic growth via human capital. However, a negative shock to natural resource rents has a negative and significant impact (with a coefficient of − 2.462) on economic growth. Public debt hurts economic growth, but the effect is statistically insignificant. While trade openness, inflation, and population positively affect economic growth, the relationship is also not statistically significant.

Furthermore, results from Nigeria show that a positive shock to total natural resource rents positively impacts economic growth, and a negative shock adversely affects growth but is statistically not significant in the long run in both cases. The positive impact of natural resource rent on economic growth contradicts the position of Idemudia (2012) that Nigeria is often a reference point for resource curse in resource-rich developing countries. However, Olayungbo (2019a) made similar findings that oil revenue positively affects economic growth in Nigeria. Public debt has a positive but statistically insignificant effect on growth, while the population also contributes positively to economic growth in the long run and is statistically significant. We identified a negative but statistically not significant link between trade openness, inflation, and economic growth.

In the case of South Africa, a positive shock to natural resource rents has statistically not a significant positive effect on growth, and negative shocks positively affect economic growth. Still, it is also statistically not significant in the long run. Public debt adversely affects the country’s growth, whereas trade openness, inflation, and population have a statistically significant positive effect on economic growth, as reported. Zahonogo (2017) also noted that, up to a certain threshold, trade openness contributes positively to economic growth in sub-Saharan African countries, but a decline sets in beyond the point reported.

Furthermore, the Wald statistic results reported in Table 11 suggest rejecting the long-run symmetry relationship between natural resource rents and economic growth in Botswana, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, and South Africa. We confirmed an asymmetric relationship between the variables in South Africa only.

Stability tests

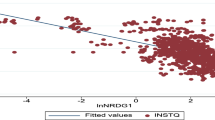

The final step is to show the dynamic multipliers, which are depicted in Figs. 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16. The dynamic multipliers reflect the adjustment trend of economic growth to positive and negative shocks to the 37-year mineral resource wealth of the respective countries. The graphics presentation shows the inverse relationship between the two variables in the Congo Republic and South Africa. One interesting that can be observed is the change between positive effects and negative effects have on the economic growth in Gabon, where positive shocks start to be negative and finally positive.

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 illustrate the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests graphs. CUSUM and CUSUM of squares are utilized to examine if the coefficients are stable or not. As a cumulative sum of recursive residuals and cumulative sum of the square of recursive residuals both are within the critical bounds at a 5% significance level, our model is stable and trustworthy to estimate the short-run and long-run coefficients.

Asymmetric causality results

Given that there exists substantial evidence of nonlinearity obtained from the BDS tests, we conclude our investigation by further assessment of asymmetric Granger causality between natural resource rents and economic growth. To test for the various countries under study, we employ the nonlinear Granger causality test of Diks and Panchenko (2006). The nonparametric results from Diks and Panchenko (2006) are reported in Table 12. The analysis was performed for embedding dimensions m = 2, 3, 4. The results show no asymmetric causality relationship between total natural resource rents and economic growth in Botswana, while a unidirectional link running from natural resource rents to economic growth was reported from the linear Granger causality results. In Congo, a unidirectional nonlinear causality running from economic growth to total natural resource rents was identified in the asymmetric framework similar to findings noted in the linear structure. No asymmetric causality was found between the variables in Equatorial Guinea and Gabon; however, in the traditional Granger causality test, we identified total natural resource rents that cause economic growth in these countries. In both linear and nonlinear Granger causality results, we confirm no feedback causality between natural resource rents and economic growth in Nigeria. The null hypothesis of nonlinear Granger causality running from total natural resource rents to economic growth is rejected only in the case of South Africa at 10% in dimension 2. In contrast, results from the linear framework reveal causality running from economic growth to total natural resource rent in South Africa. No asymmetric causality relationship exists between total natural resource rents and economic growth in Sudan and Zambia, while a unidirectional linear causality link exists between natural resource rents and economic growth in these.

Concluding remarks and policy implications

This study examines the asymmetric relationship between natural resources and economic growth for a sample of eight mineral-rich sub-Saharan African countries (SSA) over the period 1981–2017 using annual frequencies. Two scenarios were examined, thus country-by-country and panel structure. In the case of country-by-country, we apply the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lags (NARDL) model proposed by Shin et al. (2014). It allows asymmetric long-run and short-run estimation in a cointegration framework. Also, we employ the pooled mean group (PMG) estimator (Pesaran and Smith 1995; Pesaran et al. 1999) to analyze the panel data. Finally, the study investigated the nonlinear causality direction between total natural resource rents and economic growth by employing the (Diks and Panchenko 2006) nonlinear causality test for each country.

We found that in Botswana, natural resource rents cause economic growth but not vice versa. While in Congo, natural resource rent does not cause economic growth, but causality was identified running from economic growth to natural resource rents. Natural resource rents cause economic growth in Equatorial Guinea; however, no significant causality was found running from economic growth to natural resource rent. A unidirectional causality from natural resource rents to economic growth was reported in Gabon. No statistically significant causality was noted in Nigeria, whereas, in South Africa, findings revealed that economic growth Granger causes natural resource rents and not vice versa. Results from Sudan and Zambia confirmed natural resources cause economic growth.

Numerous vital findings were obtained from the results of the NARDL bounds testing analysis. The nonlinear cointegration results show four significant long-run relationships between total natural resource rents, public debt, trade openness, inflation, population, and economic growth at usual significance levels for Botswana, Congo Republic, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, and South Africa. The long-run asymmetric results provided notable evidence. An increase in natural resource rents in Botswana leads to a rise in economic growth, but the effect is not statistically significant. Public debt and population growth were found to affect economic growth adversely. The natural resource curse and debt overhang were reported in the Congo Republic since the results show that an increase in both natural resource rent and public debt significantly declines economic growth in the long run. A positive shock to natural resource rent in Gabon is positively linked to economic growth, but the effect is not statistically significant, and a similar result was found in the case of the country’s public debt and economic growth relationship. Empirical evidence from Equatorial Guinea shows that an increase in natural resource rent contributes positively to economic growth, which confirms natural resource is a blessing to the economy. At the same time, public debt negatively affects growth but is not statistically significant. A rise in natural resource rents and public debt in Nigeria positively affect economic growth; however, the impact reported is statistically insignificant in the long run. Natural resource rent makes a statistically insignificant positive contribution to the growth of the South African economy, while an increase in the nation’s public debt adversely affects economic growth in the long run.

Moreover, findings from asymmetric causalities show that total natural resource rents do not cause economic growth in all the top mineral-rich countries except South Africa, where a weak causality was identified.

Our findings have some policy implications for both policy decision-makers and resource management specialists that could help to design resource and fiscal policies in the mineral-rich countries studied. We recommend that, in countries where the resource curse was found, governments must adopt prudent fiscal policies aimed at efficient spending and borrowing. There should be reasonable spending on ambitious or legacy projects, gargantuan government salaries, and fuel subsidies. More spending should be channeled into productive sectors such as education, health, and other social services to stimulate economic growth. Internal conflicts ignited in the quest to control mineral resources and revenues accrued in mineral-rich countries; for instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Niger Delta region in Nigeria must be curtailed. It will improve security in the sub-region and increase investment inflows that will positively affect growth. To recover from Dutch Disease, which causes inflation and exchange rate appreciation, which is predominant in mineral-rich countries in Africa, governments must pay particular attention to the export-based manufacturing sector to reduce the high import dependency and, in the long run, boost economic growth. Weak governance and institutional quality are major problems confronting mineral-rich countries in Africa except for Botswana, which has been documented to establish effective structures to maximize benefits from resource revenues. Political elites in natural resource-rich countries in Africa, instead of investing in productive enterprises such as creating jobs in the manufacturing sector instead, engage in rent-seeking, which adversely affect their economies. Therefore, democracy in Africa, especially in mineral-rich countries, must move beyond periodic elections and, in some cases, dictatorial regimes to promote quality institutions and accountability, which will reduce corruption. Apart from South Africa, where trade openness contributes positively to economic growth, and in Gabon, where it negatively affects growth, no significant effect was found in other countries. Both countries must, therefore, adopt trade policies.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2012) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty: Currency

Ackah-Baidoo A (2012) Enclave development and ‘offshore corporate social responsibility’: implications for oil-rich sub-Saharan Africa. Resour Policy 37(2):152–159

Ahmed S, Mortaza M (2005) Inflation and economic growth in Bangladesh: 1981 2005, WP 0604. Policy Analysis Unit, Bangladesh Bank. https://www.bangladeshbank.org.bd/research/pau.html. Accessed 10 Jan 2021

Aljarallah R (2021) An analysis of the impact of rents from non-renewable natural resources and changes in human capital on institutional quality: a case study of Kuwait. Int J Energy Econ Policy 11(5):224

Ampofo GKM, Cheng J, Asante DA, Bosah P (2020) Total natural resource rents, trade openness and economic growth in the top mineral-rich countries: new evidence from nonlinear and asymmetric analysis. Resour Policy 68:101710

Arin KP, Braunfels E (2018) The resource curse revisited: a Bayesian model averaging approach. Energy Econ 70:170–178

Atil A, Nawaz K, Lahiani A, Roubaud D (2020) Are natural resources a blessing or a curse for financial development in Pakistan? The importance of oil prices, economic growth and economic globalization. Resour Policy 67:101683

Auty R, Warhurst A (1993) Sustainable development in mineral exporting economies. Resour Policy 19(1):14–29

Auty RM, Auty RM (1990) Resource-based industrialization: Sowing the oil in eight developing countries. Clarendon Press Oxford, United Kingdom

Badeeb RA, Lean HH (2017) Financial development, oil dependence and economic growth: Evidence from the Republic of Yemen. Stud Econ Financ 34(2):281–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-07-2014-0137

Badinger H, Nindl E (2014) Globalisation and corruption, revisited. World Econ 37(10):1424–1440

Baker D, De Long JB, Krugman PR (2005) Asset returns and economic growth. Brook Pap Econ Act 2005(1):289–330

Banerjee A, Dolado J, Mestre R (1998) Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in a single-equation framework. J Time Ser Anal 19(3):267–283

Barro RJ, Martin S-IX (2004) Economic growth. J Macroecon 18:552

Bekiros SD, Diks CG (2008) The nonlinear dynamic relationship of exchange rates: parametric and nonparametric causality testing. J Macroecon 30(4):1641–1650

Bhattacharyya S, Hodler R (2010) Natural resources, democracy and corruption. Eur Econ Rev 54(4):608–621

Boserup E (1990) Economic and demographic relationships in development. Johns Hopkins University Press, USA

Broock WA, Scheinkman JA, Dechert WD, LeBaron B (1996) A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Economet Rev 15(3):197–235

Brown I (2011) The paradox of plenty: the political and developmental implications of natural resources in sub-Saharan Africa. Available at https://media.africaportal.org/documents/Backgrounder_No._10.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2021

Butkiewicz JL, Yanikkaya H (2010) Minerals, institutions, openness, and growth: an empirical analysis. Land Econ 86(2):313–328

Carbonnier G, Brugger F (2013) The development nexus of global energy. The Handbook of Global Energy Policy, p 64–78

Carmignani F, Chowdhury AR (2010) Why are natural resources a curse in Africa, but not elsewhere?: School of Economics, University of Queensland. Available at https://www.uq.edu.au/economics/abstract/406.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2021

Cincotta RP, Engelman R (1997) Economics and rapid change: The influence of population growth. No. REP-7799. CIMMYT

Corrigan CC (2014) Breaking the resource curse: transparency in the natural resource sector and the extractive industries transparency initiative. Resour Policy 40:17–30

Dauvin M, Guerreiro D (2017) The paradox of plenty: a meta-analysis. World Dev 94:212–231

Dickey DA, Fuller WA (1979) Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J Am Stat Assoc 74(366a):427–431

Diks C, Panchenko V (2006) A new statistic and practical guidelines for nonparametric Granger causality testing. J Econ Dyn Control 30(9–10):1647–1669

Dineo SS (2019) An economic examination of non-profit accountability to client-communities in South Africa. Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch

Doğan İ, Bilgili F (2014) The non-linear impact of high and growing government external debt on economic growth: a Markov Regime-switching approach. Econ Model 39:213–220

Eggoh JC, Khan M (2014) On the nonlinear relationship between inflation and economic growth. Res Econ 68(2):133–143

Entele BR (2021) Impact of institutions and ICT services in avoiding resource curse: lessons from the successful economies. Heliyon 7(2):e05961

Erdoğan S, Yıldırım DÇ, Gedikli A (2020) Natural resource abundance, financial development and economic growth: an investigation on Next-11 countries. Resour Policy 65:101559

Fagbemi F, Kotey RA (2022) Interconnections between governance shortcomings and resource curse in a resource-dependent economy. PSU Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-09-2021-0052

Fowowe B (2016) Do oil prices drive agricultural commodity prices? Evidence from South Africa. Energy 104:149–157

Frankel JA (2010) The natural resource curse: A survey. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series, RWP10-005, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Havard University

Gelb AH (1988) Oil windfalls: Blessing or curse?: A World Bank Research Publication. Oxford university press

Gonzalez A, Teräsvirta T, Van Dijk D, Yang Y (2017) Panel smooth transition regression models. Working Paper 2017:3. University of Statistics, Uppsala University. Available at: https://www.statistics.uu.se

Gylfason T, Zoega G (2006) Natural resources and economic growth: The role of investment. World Econ 29(8):1091–1115

Harris AS, Sigman R, Meyer-Sahling J-H, Mikkelsen KS, Schuster C (2020) Oiling the bureaucracy? political spending, bureaucrats and the resource curse. World Dev 127:104745

Hayat A, Tahir M (2019) Natural resources volatility and economic growth: evidence from the resource-rich region

Hayat A, Tahir M (2021) Natural resources volatility and economic growth: evidence from the resource-rich region. J Risk Financ Manag 14(2):84

Havranek T, Horvath R, Zeynalov A (2016) Natural resources and economic growth: A meta-analysis. World Development 88:134–151

Headey DD, Hodge A (2009) The effect of population growth on economic growth: a meta-regression analysis of the macroeconomic literature. Popul Dev Rev 35(2):221–248

Idemudia U (2012) The resource curse and the decentralization of oil revenue: the case of Nigeria. J Clean Prod 35:183–193

Iimi A (2007) Escaping from the resource curse: evidence from Botswana and the rest of the world. IMF Staff Pap 54(4):663–699

Ismail K (2010) The structural manifestation of the Dutch disease: the case of oil exporting countries: Int Monetary Fund 2010(103). https://doi.org/10.5089/9781455200627.001

Janda K, Quarshie G (2017) Modelling natural resources, oil and economic growth in Africa. MPRA Paper Number 76749

Jude C, Levieuge G (2017) Growth effect of foreign direct investment in developing economies: the role of institutional quality. World Econ 40(4):715–742

Karl TL (1997) The paradox of plenty: oil booms and petro-states. Studies in International Political Economy. Volume 26 University of California Press in the series. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520918696

Karras, G (2003) Trade openness and economic growth can we estimate the precise effect? Appl Econometrics and Int Dev 3(1). Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1225622

Kasekende E, Abuka C, Sarr M (2016) Extractive industries and corruption: investigating the effectiveness of EITI as a scrutiny mechanism. Resour Policy 48:117–128

Kasidi F, Mwakanemela K (2013) Impact of inflation on economic growth: A case study of Tanzania. Asian J Empirical Res 3(4):363–380

Keho Y (2017) The impact of trade openness on economic growth: the case of Cote d’Ivoire. Cogent Econ Finance 5(1):1332820

Khobai H, Kolisi N, Moyo C (2018) The relationship between trade openness and economic growth: the case of Ghana and Nigeria. Int J Econ Financ Issues 8(1):77

Klein N (2010) The linkage between the oil and non-oil sesctors: a panel VAR approach. Int Monetary Fund Working Paper 2010(118)

Koffi S (2019) Nonlinear impact of public debt on economic growth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan African countries (No. hal-02293757). Available at: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02293757/document

Kolstad I, Søreide T (2009) Corruption in natural resource management: implications for policy makers. Resour Policy 34(4):214–226

Kolstad I, Wiig A (2008) Political economy models of the resource curse: implications for policy and research. CMI Working Paper Number 2008:6. Avaialable at: https://www.cmi.no/publications

Kronenberg T (2004) The curse of natural resources in the transition economies. Econ Transit 12(3):399–426

Li Y, Naqvi B, Caglar E, Chu C-C (2020) N-11 countries: are the new victims of resource-curse? Resour Policy 67:101697

López-Villavicencio A, Mignon V (2011) On the impact of inflation on output growth: does the level of inflation matter? J Macroecon 33(3):455–464

Mahmood T, Linden M (2017) Structural change and economic growth in Schengen region. Int J Econ Financial Issues 7(1):303–311

Mallik G, Chowdhury A (2001) Inflation and economic growth: evidence from four south Asian countries. Asia Pac Dev J 8(1):123–135

Mamo FT (2012) Economic growth and inflation a panel data analysis. Master Programme Thesis Presented to Department of Social Sciences|Economics, Södertörns University. Retrieved from https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:576024/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2021

Manamperi N (2014) The short and long-run dynamics between inflation and economic growth in BRICS. Appl Econ Lett 21(2):140–145

McFerson HM (2009) Governance and hyper-corruption in resource-rich African countries. Third World Q 30(8):1529–1547

Mehlum H, Moene K, Torvik R (2006a) Cursed by resources or institutions? World Econ 29(8):1117–1131

Mehlum H, Moene K, Torvik R (2006b) Institutions and the resource curse. Econ J 116(508):1–20

Mlambo C (2022) Politics and the natural resource curse: evidence from selected African states. Cogent Soc Sci 8(1):2035911

Moshiri S, Hayati S (2017) Natural resources, institutions quality, and economic growth; a cross-country analysis. Iran Econ Rev 21(3):661–693

Muzaffar AT, Junankar PN (2014) Inflation–growth relationship in selected Asian developing countries: evidence from panel data. J Asia Pac Econ 19(4):604–628

Narayan PK, Narayan S (2010) Carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth: panel data evidence from developing countries. Energy Policy 38(1):661–666

Naseer A, Su C-W, Mirza N, Li J-P (2020) Double jeopardy of resources and investment curse in South Asia: is technology the only way out? Resour Policy 68:101702

Ndikumana L, Abderrahim K (2010) Revenue mobilization in African countries: does natural resource endowment matter? Afr Dev Rev 22(3):351–365

Ndjokou IMMM, Tsopmo PC (2017) Non-linearity between inflation and economic growth: what lessons for the BEAC Zone? Rev Econ Dev 25(2):41–62

OECD (2011) The Economic Significance of Natural Resources: Key points for reformers in Eastern Europe Caucasus and Central Asia. Available at https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/2011_AB_Economic%20significance%20of%20NR%20in%20EECCA_ENG.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2021

Öge K (2016) Which transparency matters? Compliance with anti-corruption efforts in extractive industries. Resour Policy 49:41–50

Olayungbo D (2019a) Effects of global oil price on exchange rate, trade balance, and reserves in Nigeria: a frequency domain causality approach. J Risk Financ Manag 12(1):43

Olayungbo D (2019) Effects of oil export revenue on economic growth in Nigeria: a time varying analysis of resource curse. Resour Policy 64:101469

Papyrakis E, Gerlagh R (2006) Resource windfalls, investment, and long-term income. Resour Policy 31(2):117–128

Perron P (1988) Trends and random walks in macroeconomic time series: further evidence from a new approach. J Econ Dyn Control 12(2–3):297–332

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Economet 16(3):289–326

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RP (1999) Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Am Stat Assoc 94(446):621–634

Pesaran MH, Smith R (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Econ 68(1):79–113

Peterson EWF (2017) The role of population in economic growth. SAGE Open 7(4):2158244017736094

Pollin R, Zhu A (2006) Inflation and economic growth: a cross-country nonlinear analysis. J Post Keynesian Econ 28(4):593–614

Rao RR, Jani R (2009) Spurring economic growth through education: the Malaysian approach. Educ Res Rev 4(4):135–140

Ridena S, Nurarifin N, Hermawan W, Komarulzaman A (2021) Testing the existence of natural resource curse in Indonesia: the role of financial development. Jurnal Ekonomi Studi Pembangunan 22(2):213–227

Saaed AA (2007) Inflation and Economic Growth in Kuwait: 1985-2005 - Evidence from co-integration and error correction model. Appl Econometrics Int Dev 7(1). Available at https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1249289

Sachs J (2008) Common wealth: economics for a crowded planet. The Penguin Press, New York, 2008:386

Sachs JD, Warner AM (1995) Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER Working Paper 5698. Available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w5698/w5698.pdf

Saeed KA (2021) Revisiting the natural resource curse: a cross-country growth study. Cogent Econ Finan 9(1):2000555

Sakyi D (2011) Trade openness, foreign aid and economic growth in post-liberalisation Ghana: an application of ARDL bounds test. J Econ Int Finan 3(3):146–156

Shin Y, Yu B, Greenwood-Nimmo M (2014) Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt,Springer, New York, NY, pp 281–314

Simon J (1990) Population matters: People, resources, environment and integration. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

Singh T (2011) International trade and economic growth nexus in Australia: a robust evidence from time-series estimators. World Econ 34(8):1348–1394

Smith B (2015) The resource curse exorcised: evidence from a panel of countries. J Dev Econ 116:57–73

Sovacool BK, Andrews N (2015) Does transparency matter? Evaluating the governance impacts of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in Azerbaijan and Liberia. Resour Policy 45:183–192

Stevens DL Jr, Olsen AR (2004) Spatially balanced sampling of natural resources. J Am Stat Assoc 99(465):262–278

Teles VK, Mussolini CC (2014) Public debt and the limits of fiscal policy to increase economic growth. Eur Econ Rev 66:1–15

Tiba S (2019) Modeling the nexus between resources abundance and economic growth: an overview from the PSTR model. Resour Policy 64:101503

Tiba S, Frikha M (2018) Africa is rich, Africans are poor! A blessing or curse: an application of cointegration techniques. J Knowledge Economy 11(1):114–139

Torres N, Afonso O, Soares I (2013) Natural resources, wage growth and institutions–a panel approach. World Econ 36(5):661–687

Tsani S (2013) Natural resources, governance and institutional quality: the role of resource funds. Resour Policy 38(2):181–195

Wantchekon L (2004) The paradox of “Warlord” democracy: A theoretical investigation. Am Pol Sci Rev 98(1):17–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145294

Wu Y, Zhu Q, Zhu B (2018) Decoupling analysis of world economic growth and CO2 emissions: a study comparing developed and developing countries. J Clean Prod 190:94–103

Xie X, Li K, Liu Z, Ai H (2021) Curse or blessing: how does natural resource dependence affect city-level economic development in China? Aust J Agric Resour Econ 65(2):413–448

Yıldırım S, Gedikli A, Erdoğan S, Yıldırım DÇ (2020) Natural resources rents-financial development nexus: Evidence from sixteen developing countries. Resour Policy 68:101705

Zahonogo P (2017) Financial development and poverty in developing countries: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Econ Financ 9(1):211–220

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and animal rights

The research does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ampofo, G.M.K., Laari, P.B., Ware, E.O. et al. Further investigation of the total natural resource rents and economic growth nexus in resource-abundant sub-Saharan African countries. Miner Econ 36, 97–121 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00316-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00316-4