Abstract

Using data from administrative registers for the period 1970–2007 in Norway and Sweden, we investigate the intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility. We find that men and women with half-siblings are more likely to have children with more than one partner. The differences are greater for those with younger versus older half-siblings, consistent with the additional influence of parental separation that may not arise when one has only older half-siblings. The additional risk for those with both older and younger half-siblings suggests that complexity in childhood family relationships also contributes to multipartner fertility. Only a small part of the intergenerational association is accounted for by education in the first and second generations. The association is to some extent gendered. Half-siblings are associated with a greater risk of women having children with a new partner in comparison with men. In particular, maternal half-siblings are more strongly associated with multipartner fertility than paternal half-siblings only for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, the family lives of many children have become less stable and more complex (Carlson and Meyer 2014; Manning et al. 2014; Thomson 2014). Children are increasingly likely to experience their parents’ separation, perhaps acquire a stepparent, and sometimes a half-sibling or two. Even children who remain in stable families may have an older half-sibling from a parent’s prior partnership. Growing up in a complex family provides experiences that may facilitate or encourage similar family trajectories.

A considerable body of research has found an association across generations in partnership stability and fertility. Intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility is the cumulative outcome of the two family transitions, but growing up with half-siblings adds a dimension of complexity to family life that goes beyond the sum of partnership and fertility behavior. In this study, we investigate the intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility: that is, the association between having half-siblings and the risk of having children with more than one partner.

We take advantage of administrative registers in Norway and Sweden that link children with each of their parents across three generations and over a period of 40 years. As far as we know, this is the first nationally representative study including information on half-siblings from both parents, together with information on the other parent for each of the second generation’s children. We use detailed information about sibling order and common parents to distinguish experiences of parental separation, which occurs before younger half-siblings are born, and sharing a household with half-siblings, which is most likely with half-siblings on the mother’s side. We also investigate the extent to which the intergenerational associations remain when we account for mother’s and own educational attainment and/or family behaviors in the second generation that serve as pathways to multipartner fertility. In addition, we investigate whether there are gender differences in intergenerational transmission. By replicating our analyses in two Nordic contexts, we provide initial evidence that the intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility is a general process.

Multipartner Fertility and Complex Families

Before divorce became common, widow(er)hood and remarriage could produce sibships of children with different sets of biological parents. But these siblings usually lived in the same household—that of the surviving parent—and had only one living father or stepfather, and one mother or stepmother, thus reproducing the configuration of a nuclear family. Today’s multipartner fertility instead produces family relationships across households, with a consequent increase in complexities of family life.

From the parents’ point of view, the birth of half-siblings has been termed “multipartner fertility” (Furstenberg and King 1999). Over recent decades, increases in parental separation have generated an increase in multipartner fertility (Guzzo and Furstenberg 2007; Lappegård and Rønsen 2013; Manning et al. 2014; Thomson et al. 2014). From the early 1990s to the early 2000s, the risk of parental separation by age 15 increased or remained at high levels throughout Europe and in the United States (Andersson 2002; Andersson et al. 2017). Approximately one-half of children born to a lone mother or experiencing parental separation enter a stepfamily within six years (Andersson et al. 2017). Of stepfamily couples in their reproductive years, approximately one-half have a child together (e.g., Holland and Thomson 2011; Thomson et al. 2002; Vikat et al. 1999). Thomson et al. (2014) reported that among mothers with at least two children, almost one-third in the United States had children with different fathers, while the corresponding figures for Australia, Norway, and Sweden were between 10 % and 15 %.Footnote 1 The percentages are, of course, higher the more children one has; large families of three or more children are highly likely to comprise full and half-siblings (Sobotka 2008; Thomson et al. 2014). In Sweden, the percentage of persons with a half-sibling increased from approximately 15 % for the 1930s and 1940s cohorts to 30 % for those born in the 1980s and later (Statistics Sweden 2013; Turunen and Kolk 2017). The reproduction of multipartner fertility across generations could thus dramatically increase the future prevalence of complex families.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Multipartner Fertility: Concepts, Pathways, and Mechanisms

Multipartner fertility in the first generation dictates that children in the second generation have half-siblings. Thus, the question about intergenerational transmission becomes whether and to what extent having half-siblings is associated with partnership and childbearing trajectories in adulthood that produce half-siblings in the third generation.

The second generation’s experiences of half-siblings depend on their place in their parents’ partnership and childbearing trajectories. Children may have half-siblings from birth because one or both of their parents had children with a previous partner. They may grow up with both parents and experience no further family transitions. Children with younger half-siblings have experienced their own parents’ separation or divorce, and have subsequently acquired a stepparent. Half-sibling experiences are also likely to differ depending on which parent the half-siblings have in common. Because most children live with their mother after parental separation, half-siblings from the mother are more likely to share a household than half-siblings from the father. These differences have implications for the theoretical mechanisms through which multipartner fertility may be transmitted across generations.

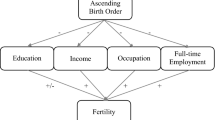

Intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility also depends on a complex trajectory of partnerships and childbearing in the second generation. At a minimum, the trajectory includes having a child, separating from the other parent of that child, repartnering (i.e., forming a stepfamily), and having a child with a new partner. Other family transitions may also be part of this sequence: early union formation and childbearing, and childbearing in cohabitation versus marriage. The intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility may therefore rest on the transmission of union formation and dissolution patterns or on the timing and union context of first birth.

The two dominant explanations for the intergenerational transmission of family behavior in general are direct socialization and indirect transmission through the transmission of social and economic resources, especially education. Through socialization, parents transmit to their children family values, norms, ideals, and practices that frame the children’s family choices in adulthood (Barber 2000). They may do so consciously through teaching or unconsciously by their own behaviors—that is, providing models of what is acceptable and providing information about the consequences of particular family choices.

Through the intergenerational transmission of social and economic resources, children are provided with incentives and opportunities for socioeconomic achievements that in turn generate resources for a more stable family life (Härkönen et al. 2017; McLanahan and Percheski 2008). Social and economic resources may also be direct consequences of family behavior in the first generation: for example, economic losses after parental separation and/or the addition of a stepparent’s resources to the family (Ginther and Pollak 2004; McLanahan and Percheski 2008).

A third mechanism has been proposed for the transmission of family instability: the stress associated with accumulated family change during childhood (McLanahan and Bumpass 1988; Wu and Martinson 1993). Stress is thought to operate through lowering children’s achievements as well as their capacity for the formation and maintenance of intimate relationships. What has not been noted is the fact that multiple family transitions usually generate more complex families (cf. Fomby et al. 2018). Repartnering after separation adds a stepparent to the household. Having a child with the new partner adds a half-sibling. Family complexity itself can be a source of stress. Rights and responsibilities are less clearly defined in law, and normative expectations for family relationships and behavior are relatively weak (Cherlin 1978; Ganong and Coleman 2006; Rossi and Rossi 1990). Family members may not even agree on who “belongs” to the family (Stewart 2005a; Zartler 2011). The maintenance of family relationships across households also generates greater organizational and behavioral challenges than when all family members live together (Cherlin and Seltzer 2014; Furstenberg 2014).

A potential fourth explanation for the intergenerational transmission in general is that parents and children share genetic capacities that predispose them to particular outcomes: for example, high educational achievement or stable partnerships (D’Onofrio and Lahey 2010). Genetic similarities may underlie or augment socialization and resource mechanisms for intergenerational transmission.

An overarching dimension of intergenerational transmission is gender. Socialization theory posits that parents act as gendered role models for their children, with daughters modeling mothers’ behavior, and sons modeling fathers’ behavior (Pope and Mueller 1976; Raley and Bianchi 2006). The relative absence of male role models after separation or divorce is posited to generate more negative consequences for boys than for girls (Lyngstad and Engelhardt 2009; Pope and Mueller 1976). On the other hand, sons of separated parents are more likely than daughters to live full- or part-time with the father; they also have more face-to-face contact and closer relationships than do daughters (Kalmijn 2015). Thus, their opportunities for same-sex modeling may be sufficient to generate a strong intergenerational association between fathers’ and sons’ family behaviors.

The acceptability of separation, divorce, repartnering, and childbearing with new partners would likely be greater for both sons and daughters whose parents divorced. Gender socialization makes women, however, more sensitive to relationship quality so that stresses from multiple family changes or complex relationships may be greater for girls than boys, leading to stronger intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility (Kalmijn and Poortman 2006; Lyngstad and Engelhardt 2009).

Evidence for Intergenerational Transmission of Family Behaviors: Pathways and Mechanisms

The most comprehensive body of evidence for the intergenerational transmission of family behaviors is for divorce (Amato 1996; Diekmann and Schmidheiny 2013; Dronkers and Härkönen 2008; Glenn and Kramer 1987; McLanahan and Bumpass 1988; Wolfinger 1999, 2005, 2011). Parental divorce is also associated with early and nonmarital childbearing (Amato and Kane 2011; Barber 2001; Cherlin et al. 1995; Hofferth and Goldscheider 2010; Högnäs and Carlson 2012; McLanahan and Bumpass 1988; Teachman 2004), both of which are in turn associated with multipartner fertility. On the other hand, McLanahan and Bumpass (1988) reported higher likelihood of remarriage after divorce for those who lived with both parents than those who did not. Parental separation or divorce has been shown to have an independent association with multipartner fertility for women (Carlson and Furstenburg 2006) but not for men (Guzzo and Furstenburg 2007).

Only a few studies have considered the effects of stepparent experience on a child’s subsequent family life. Associations are found with nonmarital childbearing (Amato and Kane 2011; Fomby and Bosick 2013; but see McLanahan and Bumpass 1988), and separation or divorce (Washington 2018; Wolfinger 2005). The more complex family experience of having half-siblings has not been studied for second-generation family behaviors.

Because the final step in producing a complex family is having a child with a new partner, and because families with half-siblings are larger than those without, the intergenerational transmission of fertility may play a role in the intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility. One of the stronger associations is between mothers’ and children’s early childbearing (Barber 2000; Furstenberg et al. 1990; Steenhof and Liefbroer 2008). Högnäs and Carlson (2012) found an association between parents’ and children’s nonmarital childbearing. As noted earlier, early and nonmarital childbearing are associated with multipartner fertility. Intergenerational transmission of family size (Cools and Hart 2017; Kolk 2014; Murphy and Knudsen 2002; Murphy and Wang 2001) is also a potential mechanism because it would increase the likelihood of preferences for the larger numbers of children produced by childbearing with a new partner (Kohler et al. 1999).

Considerable direct and indirect evidence exists for socialization mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of divorce (Amato 1996; Amato and DeBoer 2001; Diekmann and Engelhardt 1999; Glenn and Kramer 1987; McLanahan and Bumpass 1988; Wolfinger 2005) and for the relationship between parental divorce and nonmarital childbearing (Amato and Kane 2011; Cherlin et al. 1995; McLanahan and Bumpass 1988; Teachman 2004). Because the intergenerational transmission of more complex family pathways is rare, we must infer the potential for socialization mechanisms by examining families when the children (second generation) are still at home.

Several studies have documented lower parental engagement in stepfamilies, including that of the repartnered mother (e.g., Evenhouse and Reilly 2004; Hofferth 2006; Hofferth and Anderson 2003; Marsiglio 1992; Thomson et al. 1994, 2001). Findings are quite mixed about the way in which the birth of a younger half-sibling alters those relationships. Some studies have found no differences across families (Cooksey and Fondell 1996; Ganong and Coleman 1988; Stewart 2005b), whereas others have found that stepchildren are disadvantaged in terms of their relationships with parents in comparison with younger half-siblings (Evenhouse and Reilly 2004; Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2008). In adulthood, relationships between full siblings are stronger than those between half-siblings (Tanskanen and Danielsbacka 2014; White and Riedmann 1992), but differences are smaller the longer the half-siblings have lived together (Bressan et al. 2009; Pollet 2007). No direct evidence is available, however, that links these socialization experiences to family behaviors in adult life.

All studies of associations between parents’ and children’s family behaviors have included controls for the indirect mechanism of socioeconomic transmission. Most commonly, models include the child’s education, apparently under the assumption that it captures the influence of parental social and economic resources. A few studies have included education in both generations, with usually greater explanatory power. Studies of early family transitions have typically included only the parents’ education, given that children’s educational attainment may be a consequence as well as a determinant of early family formation. Such controls account for some but usually not the larger share of the association between parents’ and children’s family behaviors.

Again, however, we have relatively little evidence for the role of social and economic resources in the intergenerational transmission of more complex family trajectories. We can again draw inferences from family structure differences in childhood (i.e., children’s cognitive and educational attainments). Children in stepfamilies achieve at lower levels than those in stable two-parent families, but much of the difference arises from the more complex stepfamilies with half-siblings (Cooksey and Fondell 1996; Evenhouse and Reilly 2004; Ginther and Pollak 2004; Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2008; Strow and Strow 2008; Sundström 2013; Tillman 2008a, b; Turunen 2014). Achievement gaps are most common and pronounced for the older half-siblings, who have also experienced parental separation. Turunen (2014) demonstrated further that children with paternal half-siblings, both older and younger, have lower achievement than those with maternal half-siblings. Thus, through the reduction of social and economic resources in their own adult lives, those who lived with half-siblings—especially in the most complex sibling compositions—could be expected to exhibit less-stable family behaviors in adulthood than those who did not.

Most studies to date have found that having children with more than one partner is associated with lower education (Carlson and Furstenberg 2006; Guzzo and Furstenberg 2007). Thomson et al. (2014) controlled also for the maternal grandmother’s education but found no association in Australia and the United States. In Norway and Sweden, the grandmother’s education was positively associated with new-partner childbearing, even without controlling for the mother’s education. They attributed the finding to the fact that the grandmothers in question were among the pioneers in changing family norms.

The stress mechanism—as represented by number of family changes—is supported for the intergenerational transmission of divorce (Wolfinger 2000, 2005; Wu 1996; Wu and Martinson 1993). Hofferth and Goldscheider (2010) reported that number of transitions was also associated with early childbearing, but Fomby and Bosick (2013) found no association with a cohabiting parent trajectory in young adulthood. In most of the studies, controls were included for the particular family configurations to which children were exposed. Because particular configurations are strongly associated with number of transitions (e.g., parental separation as the first transition, entry into a stepfamily occurring as the second transition, birth of a half-sibling as the third), the adequacy of such controls is not entirely clear.

The stress mechanism may also be inferred from the fact that children in stepfamilies experience no better and sometimes poorer psychological well-being than children living with single mothers (Evenhouse and Reilly 2004; Sweeney 2007; Thomson et al. 1994; Turunen 2014). The fact that younger half-siblings who live with both biological parents are also found to have lower psychological well-being is consistent with the role of complexity per se in generating family stress (Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2008; Harcourt et al. 2015; Strow and Strow 2008). Thus, we can conclude that multipartner fertility in the parent generation can be a source of stress, but we have no evidence about effects of such stress on family behaviors in the child generation.

All three mechanisms may underlie gender differences in the intergenerational transmission of family behavior. Among those who experienced parents’ divorce, women are more likely to divorce than men (Amato 1996; Feng et al. 1999; Glenn and Kramer 1987; Lyngstad and Engelhardt 2009). Parental divorce and/or death is also associated differentially with women’s and men’s early and nonmarital childbearing, with larger differences for women than for men (Cherlin et al. 1995; Hofferth and Goldscheider 2010). The intergenerational transmission of fertility behavior is stronger between same-sex parent-child dyads than opposite-sex dyads (Axinn et al. 1994; Barber 2001; Kahn and Anderson 1992; Murphy and Knudsen 2002; Rijken and Liefbroer 2009; Steenhof and Liefbroer 2008). The differences arise from mother’s behavior affecting daughters more than sons, while father’s behavior affects sons and daughters equally (Riise et al. 2016; Rijken and Liefbroer 2009). Högnäs and Carlson (2012) reported that parents’ nonmarital childbearing is associated only with daughters’ (not sons’) nonmarital first births.

Implications for the Intergenerational Transmission of Multipartner Fertility

Theory and evidence point to a number of pathways and mechanisms through which multipartner fertility could be transmitted across generations. Thus, our primary hypothesis is that having half-siblings is directly associated with the likelihood of having children with more than one partner. The socialization mechanism of family behavior implies that children with younger half-siblings will be more likely to do so because they have experienced parental separation and have had poorer role models for maintaining a stable partnership. Even younger half-siblings, however, learn from their parents that divorce, repartnering, and having children with a new partner is acceptable.

Indirect transmission of family behavior through the transmission of social and economic resources points to a reduction in half-sibling differences when parents’ educational attainment is controlled. We further hypothesize that some of the association will be accounted for by intermediate educational attainment of the second generation and family behaviors prior to the prospective birth that might be pathways toward multipartner fertility (i.e., early and nonmarital first births).

The stress mechanism for transmission of family behaviors provides clearer predictions for differences among those with different types of half-siblings. First, children with only older half-siblings have experienced fewer family transitions than those with younger half-siblings and should therefore be less likely to have children with more than one partner. Additional stress from complex family relationships and organizational requirements leads to the hypothesis that those with both older and younger half-siblings would be more likely than those with only younger or only older half-siblings to have children with more than one partner. The stress mechanism also suggests that half-siblings with a common mother would be more likely to have children with more than one partner than would half-siblings with a common father.

From the socialization perspective, half-siblings from the same-sex parent should have a stronger influence on subsequent childbearing with more than one partner (i.e., through modeling). Half-siblings from the mother, however, are likely to live with each other, providing a more visible model of mother’s behavior and therefore a stronger socialization influence for sons as well as daughters. Gender differences in sensitivity to multiple family changes and complexity in family relationships predict stronger influences of any half-siblings, but particularly coresident half-siblings, on women’s than men’s multipartner fertility.

Data and Methods

We use individual-level data from national administrative registers for the period 1970–2007 for the entire Norwegian and Swedish population. Each resident has a unique identifying code that makes it possible to construct longitudinal data from different information sources. In both countries, population registers contain records of every person who has ever lived in the country since 1960. We are able to link the father and the mother of each child to determine whether a given birth is with the same or different partner for other births. By parents, we refer to the legal parents given that this is the only parent recorded in the Norwegian registers. In Sweden, we use adoptive (legal) parents when data are available also for a biological parent. We have such information across three generations to link multipartner fertility in the grandparent generation to that of the parent generation. Thus, without reference to marriage or union histories, we are able to determine whether a second or higher-order birth is with the same man/women as earlier births and whether each prospective parent’s siblings were all born to the same mother and father.

We follow the second generation of women and men born between 1952 and 1979 who had at least one child born at ages 16–45 (women) or 16–49 (men). We exclude individuals not born in Norway/Sweden because we do not have complete information about their parents or siblings. The abundant data allow analyses of relatively small groups, such as families with different configurations of half-siblings, that are normally not feasible with sample surveys. Register data are recorded contemporaneously so that the quality and completeness of reports are not dependent on the nature of the relationship between the parent and the child over time.

Through the parent-child connections, we are able to identify siblings with the same mother and father or with only the same mother or only the same father (half-siblings). We also define siblings as half-siblings if information about one of the parents is unknown. Such cases are rare and, because of registration procedures, not random. Most likely, the other parent has never been in the country (and thus is not registered), or the mother refuses to identify the father for personal reasons or because she does not know who the father is. If a parent is identified for one child, she/he would be identified for any other common children. Thus, any unknown parent can be presumed to be a different person than the parent of an earlier- or later-born child. We consider two sibling compositions: one in which half-siblings are classified by age (only older, only younger, or both older and younger) and one in which they are classified by parent (only mother, only father, or both parents).

The distribution of half-siblings in the second generation is shown in Table 1. First, 22 % of Swedes and approximately 11 % of Norwegians had any half-siblings. The difference stems from a somewhat longer history of births in cohabitation, union dissolution, and repartnering in Sweden than in Norway, countering the higher proportion of children born to a lone mother in Norway. Second, compared with Swedes, Norwegians are more likely to have maternal half-siblings than paternal half-siblings. This difference could arise from the larger proportion of children born to lone mothers in Norway, with fathers who are not identified in the register. When lone mothers have a second child, it is highly likely to be with another man.

Parents’ and children’s social and economic resources are represented by mother’s (first generation) education.Footnote 2 Education for the second generation is measured at the end of the observation period, 2007; education for the first generation is measured when the second generation is 16 years old in Norway and as close as possible to age 16 in Sweden.Footnote 3 Both educational variables have three levels: compulsory only (10 years of schooling), secondary (11–13 years), and college or university (14 or more years).

We include several indicators of second-generation partnership and fertility behavior that also might mediate intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility: parity in the first childbearing partnership (one, two, three, four or more children), age at first birth (under 20 years, 20–25, 26–29, 30 years and older), and marital status at first birth (unmarried or married). All three second-generation indicators are associated with parental (first generation) partnership or fertility and also with the risk of having a second- or higher-order birth with a new partner (Lappegård and Rønsen 2013; Thomson et al. 2014). Those not married at first birth include both those living in coresidential cohabitation and those not living with the other parent of their child; in Norway and Sweden, the vast majority of these parents were cohabiting at birth. In both Norway and Sweden, the majority of firstborn children have parents who are cohabitors; the proportion of lone parents is somewhat lower in Sweden than in Norway. Cohabiting parents are more likely to separate than married parents (Andersson 2002; Manning et al. 2004). Consequently, unmarried women and men are less likely to have stable union histories and are therefore at greater risk of having children with a new partner (Lappegård and Rønsen 2013). Last, we include sex and birth cohort (1952–1959, 1960–1969, and 1970–1979) of the second generation. Birth cohort controls for common trends in union instability and multipartner fertility to isolate the association across generations.

Because childbearing is an ongoing process and we have access to longitudinal data, we model the intergenerational association as an association between half-siblings produced by the first generation and the risk of producing a half-sibling in the second. We begin observing each second-generation woman or man in the month of her/his first child’s birth. If the second child is born to the same couple, we begin observation again, but this time at parity 2. If the second child’s other parent is different than the first, we count it as “multipartner fertility” and exclude further observations from our analysis. That is, we estimate the risk of a first birth with a new partner, or ever producing a half-sibling for one’s older children who (if two or more) are full siblings. The number of birth intervals that we observe for each second-generation person is therefore the number of children born to the same couple as the first. For example, parents who had one child with each of two different partners are observed only for the second birth interval until they have the child with the new partner. Those who had two children together are observed between the first and second child and after the second child. Multiple births are treated as a single event, born to either the same or a new partner than previous children. We censor after a multiple birth with the same partner because of the likely unique consequences of multiple births for further childbearing. Thus, if a woman’s or man’s first birth is a multiple birth, she/he does not contribute any exposure time to the estimation. Finally, we censor at the earliest of the following events: a woman reaches age 45 or a man reaches age 49; the person dies; the last observation occurs (in 2007); or the youngest child reaches age 10.

Table 1 shows the number of women and men observed, the number of birth intervals observed, and the distributions for all covariates. Except for parity in the first childbearing partnership, all variables are fixed at the first birth. Percentages for the time-constant covariates are based on the number of persons observed. Percentages for parity in the first childbearing union are based on the number of birth intervals observed across the population.

Because the observations are so many, duration at risk is measured in calendar years since the previous birth (months after the previous birth divided by 12 and rounded down) to facilitate computation. We use discrete-time multinomial logistic regression to estimate the competing risk of a birth with the same partner, a birth with a new partner, or no birth. Duration dependence is specified as a linear and squared function of years since the previous birth. We show results only for the risk of having a birth with a new partner compared with a birth with the same partner. Alternative model parameters (each type of birth in relation to no birth) are available on request.

Results

Intergenerational Transmission of Multipartner Fertility

Tables 2 and 3 present estimates from the discrete-time hazard model for the risk of having a child with a new partner relative to the risk of having a child with the same partner. The models are the same in the two tables except for the specification of half-siblings. In Table 2, we present the model for half-siblings by age; in Table 3, we present the model for half-siblings by parent. In analyses not shown, we investigate distinctions between different types of half-siblings (older, younger, both; from mother, father, both) by comparing model fit when all half-sibling categories were combined with the models presented. Fit was much improved with the full categorization of half-siblings.

For each analysis, we first present a baseline model (M1) with only the half-sibling variable. The second model (M2) adds educational attainment in the first generation to distinguish influences of parental education from influences of parental partnership and fertility on children’s family behavior. The third model (M3) adds educational attainment of the second generation to more fully test the mechanism of indirect transmission of family behavior via social and economic resources. Last, in the fourth model (M4), we add indicators of the second generation’s family behavior before the prospective birth (age and union status at first birth, and number of births with the same partner) to test behavioral pathways toward multipartner fertility, as well as the parent’s own birth cohort (controlling for change) and sex.

First, the baseline model in Table 2 shows a positive association between having half-siblings and having a child with a new partner versus the same partner, independent of whether the half-siblings are older, younger, or both. This confirms our general hypothesis that there is an intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility. Second, the risk of having a child with a new partner is higher for those with only younger half-siblings than for those with only older half-siblings (relative risk of 2.90 vs. 1.74 for Norway; relative risk of 2.34 vs. 1.78 for Sweden). This result is consistent with the greater number of transitions (and associated stress) experienced by the older half-sibling whose parents have separated and who acquired a stepparent as well as a younger half-sibling. Third, the highest relative risk of having a child with a new partner is found for those with both older and younger half-siblings (3.34 in Norway and 3.01 in Sweden), consistent with having experienced stress from relationship complexity.

The baseline model in Table 3 also shows a greater risk of childbearing with a new partner for those with half-siblings, whether on the mother’s or the father’s side. Again, the relative risk is highest for those with half-siblings from both their mother and their father (relative risk of 3.65 in Norway and 2.86 in Sweden). The risk is higher for those with only maternal half-siblings than for those with only paternal half-siblings (relative risk of 2.15 vs. 1.88 for Norway; relative risk of 2.05 vs. 1.87 for Sweden). These results are consistent with coresident siblings producing greater stress or stronger modeling than noncoresident siblings.

We now turn to the results from the models controlling for educational attainment and for partnership and fertility behavior. In Table 2, the magnitude of the half-sibling differentials are only negligibly smaller when we control for first generation’s educational attainment. For example, the relative risk of having a higher-order birth with a new partner is reduced in Norway from 3.34 to 3.27 for those having both older and younger half-siblings. In Sweden, the corresponding reduction is from 3.01 to 2.96. When we add educational attainment in the second generation, the differentials are reduced to a greater but still very small degree: 2.97 in Norway and 2.70 in Sweden. When we control for marital status and age at first birth, we see larger reductions in relative risks, to 1.62 in Norway and to 1.96 in Sweden. Differences in relative risk between those with only older and only younger half-siblings are also reduced when we control for educational attainment, marital status, and age at first birth in the second generation, but the relative risk is still higher for those with only younger than only older half-siblings. The fact that almost all the differences associated with the grandmother’s education are accounted for by the mother’s (own) education indicates that educational transmission occurs primarily through influencing education in the second generation rather than through direct influences on family behavior in the second generation. Although we find evidence that the transmission of multipartner fertility is in small part due to the intergenerational transmission of social and economic resources and partly mediated by the transmission of early or nonmarital first births, remaining differences are quite substantial. Because relative risks are not strictly comparable across logistic models, we calculated average marginal effects corresponding to each sibling comparison for Models 1–4. Differences across models in the estimated effects were consistent with our interpretation of the changes in relative risks. (Estimates are available on request.)

When half-siblings are distinguished in terms of the common parent (Table 3), we also find reductions in the magnitudes of each half-sibling differential when controlling for mother’s educational attainment, and we find further reductions when controlling for educational attainment of the second generation. In Norway, the relative risk for those with both paternal and maternal half-siblings is reduced from 3.65 to 3.58 and further to 3.31. In Sweden, controls for (grand)mother education produce negligible differences (2.86 to 2.83), while own education reduces the difference to 2.62. Much larger reductions are seen when we control for marital status and age at first birth: to 1.62 in Norway and to 1.90 in Sweden. However, when we control for marital status and age at first birth in the second generation, only in Norway do we still find a small difference between those with only maternal half-siblings and those with only paternal half-siblings in the relative risk of childbearing with new partners. Again, we calculated average marginal effects for each of the models, and the results were consistent with inferences from the relative risks.

Gender Differences in Intergenerational Transmission of Multipartner Fertility

So far, we have investigated the intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility for men and women together, although we control for sex in the full models. An interesting observation from these analyses is that in Norway, women are much more likely to have children with more than one partner than men (relative risk is 1.26 among women compared with men), while in Sweden, the gender gap is smaller (relative risk of 1.07 among women compared with men). This might be related to Norway having a larger proportion of lone mothers than Sweden, women who are at particularly high risk of forming new partnerships and having children with new partners.

To examine whether the relationship between having half-siblings and the likelihood of having children with a new partner plays out differently for men and women, we estimate the full model with an interaction term between the half-sibling variables and sex of the analysis person.Footnote 4 To illustrate the main results from these models, we compute relative odds ratios of births with a new partner versus the same partner for women and men, presented in Tables 4 and 5.

The overall picture for both women and men is quite similar, but the magnitude of the differences varies by sex. Differences according to half-sibling composition in the relative risk of having a child with a new partner are larger for women than for men in both Norway and Sweden. For both men and women, those with only younger half-siblings compared with those with only older half-siblings have higher risk of having a child with a new partner, but the gaps are greater for women. The additional risk associated with having both younger and older siblings is smallest for Norwegian men, but similar for Swedish men and Norwegian and Swedish women.

The most noticeable difference is in the influence of maternal versus paternal half-siblings. In Sweden, the risk is about the same for those with only maternal versus those with only paternal half-siblings, and this holds for both men and women. No differences for maternal versus paternal half-siblings were found for Norwegian men, but Norwegian women were more likely to have a child with a new partner if they had only maternal half-siblings than if they had only paternal half-siblings. As noted earlier, maternal half-siblings are much more common in Norway than in Sweden. Gender differences are observed in both countries for those with both paternal and maternal siblings; the relative risk of having a child with a new partner is, respectively, 2.17 and 1.48 for women and men in Norway, and 2.00 and 1.74 for women and men in Sweden.

Discussion

As for most other industrialized countries, union dissolution and divorce rates have been increasing over the last decades, producing a larger population of mothers and fathers at risk of having children with a new partner. In both Norway (11 %) and Sweden (22 %), a significant proportion of the population has half-siblings. The higher incidence in Sweden reflects earlier increases in divorce and cohabitation—that is, the experience of the first generation in our study. In the second generation, it is Norwegian women, in particular, who are more likely to have had children with more than one partner (Thomson et al. 2014). Although both countries have long histories of state support for parenthood (parental leave, public childcare, leave for care of sick children, and child allowances), historically Norway has provided more generous income transfers to single parents, and a higher proportion of first births occur among women living alone. Thus, the pool of women at risk of having their second child with a new partner is much greater, especially in the more recent cohorts of parents who experienced more generous transfers than earlier cohorts. Because Sweden’s parental leave provides an incentive for the close spacing of births, a higher proportion of women have their first two births before they are at high risk of separation from the first father (Thomson et al. 2014). The more children one has with the first father/mother, the less likely is further childbearing with a new partner.

Our study investigates the intergenerational transmission of multipartner fertility, which is a cumulative outcome of the two family transitions: partnership stability and fertility. Following the socialization mechanism, growing up with half-siblings provides role models who have experienced separation and repartnering, generating more acceptance for a family pathway including children with more than one partner. As we expected, we find a positive association in both Norway and Sweden between having half-siblings and the risk of childbearing with a new partner. The fact that those with only older half-siblings are less likely to have children with new partners than those with only younger half-siblings is consistent with relative exposure to role models for separation and repartnering. Socialization processes are also indicated by the fact that having half-siblings is associated with a greater increase in the risk of women having a child with a new partner, in comparison with men (Amato 1996; Feng et al. 1999; Glenn and Kramer 1987; Lyngstad and Engelhardt 2009). The fact that maternal half-siblings produce slightly higher risks of having children with new partners only among women in Norway is also consistent with gender-specific socialization for fertility behavior (Riise et al. 2016; Rijken and Liefbroer 2009). Still, childbearing with new partners is not more strongly related to having paternal half-siblings for men than for women.

The half-sibling differentials are slightly reduced when we control for education of the prospective parent and her/his mother (i.e., the grandmother to a prospective child). Thus, intergenerational transmission of educational attainment accounts for a small part of the intergenerational association in multipartner fertility.

The stress mechanism is evidenced in the greater risk of childbearing with new partners for those with only younger half-siblings than for those with only older half-siblings because the former experience more family changes. We cannot disentangle socialization from stress mechanisms in this comparison. The stress mechanism is also consistent with the fact that those with the most complex sibships—that is, having both older and younger half-siblings and/or both maternal and paternal half-siblings—are most likely to have children with more than one partner. Stress mechanisms can also be inferred from the fact that those with maternal half-siblings are more likely to have a child with another partner than those with paternal half-siblings, given that maternal half-siblings likely live with each other and paternal half-siblings likely do not. The fact that these observed differences are accounted for mostly by differences in marital status and age at first birth does not, however, rule out the influence of stress on having children with a new partner.

The pattern of intergenerational associations for multipartner fertility is very similar in Norway and Sweden. We expect similar patterns in other societies with high levels of union instability and fertility levels near or at replacement (2.1 children per woman). The data for such studies are, however, rare. Where population registers with links between parents and children are not available, one could investigate the question with large-scale surveys—but only if they incorporate questions about both parents’ union and birth histories, or at least collect data on the ages and common parent of respondents’ half-siblings.

We note, of course, a number of limitations to our study. Although the Nordic register data enable us to identify the full complement of an individual’s half- and full sibship, they do not provide information about other dimensions of family experience that might be sources of the intergenerational association we model. Many individuals—those with full and/or half-siblings—may have had stepparents and/or stepsiblings. To identify such relationships requires identification of remarriages and, after the 1960s, identification of repartnering through cohabitation. The registers do not provide information on marriage or divorce until 1968. Only from 2005 in Norway and 2011 in Sweden is it possible to estimate cohabitation for persons who did not have a common child. Thus, the number of transitions experienced by those with and those without half-siblings cannot be fully counted. It is possible to identify first-generation parents who had children with more than two different partners, but the proportions are small and would not add to the basic findings. As the younger cohort ages, and with new data on dwellings, it will be possible to identify not only half-siblings but also stepsiblings. For instance, it could be a natural next step for future research to test the influence of how long children have lived in households with a particular sibship composition for transmission of multipartner fertility.

Our study has implications for public policy. Increasing and high levels of union instability during the childbearing ages have produced increasing proportions of parents who have children with more than one partner. In line with our finding that such fertility patterns are associated across generations, we anticipate no reductions but likely increases in the proportion of families with complex sibships and family organization. In “simple” families with a mother, father, and their shared biological children living together, parents can more easily spend time with children, determine together how resources will be allocated to children, and have clearer definitions of parental and child rights and responsibilities. When parents live apart from their children—some or all of the time—and have children with other partners, all these dimensions of family life are complex and often ambiguous. Family law and institutional supports for children and their parents have not kept up with changes in family behavior (Meyer et al. 2005). Complex families have always existed but today are more numerous and present greater challenges to institutional arrangements based on the traditional nuclear family.

Notes

We also estimated models with father’s education in the first generation, both mother’s and father’s education, and the highest education in the first generation; results were essentially the same as those reported in this article.

In Sweden, education was not registered annually until 1985; a measure of parents’ education was available from the 1970 census, used for those who reached age 16 between 1968 and 1984.

Because we observe the entire populations and particularly because the number of observations is so large, statistical tests of model fit or specific interaction contrasts are not particularly meaningful. We discuss instead the size of differences between the intergenerational associations for women and men.

References

Amato, P. R. (1996). Explaining the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 628–640.

Amato, P. R., & DeBoer, D. D. (2001). The transmission of marital instability across generations: Relationship skills or commitment to marriage? Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1038–1051.

Amato, P. R., & Kane, J. B. (2011). Parents’ marital distress, divorce, and remarriage: Links with daughters’ early family formation transitions. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 1073–1103.

Andersson, G. (2002). Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: Evidence from 16 FFS countries. Demographic Research, 7(article 7), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2002.7.7

Andersson, G., Thomson, E., & Duntava, A. (2017). Life-table representations of family dynamics in the 21st century. Demographic Research, 37(article 35), 1081–1230. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.35

Axinn, W. G., Clarkberg, M. E., & Thornton, A. (1994). Family influences on family-size preferences. Demography, 31, 65–79.

Barber, J. S. (2000). Intergenerational influences on the entry into parenthood: Mothers’ preferences for family and non-family behavior. Social Forces, 79, 319–348.

Barber, J. S. (2001). The intergenerational transmission of age at first birth among married and unmarried men and women. Social Science Research, 30, 219–247.

Bressan, P., Colarelli, S. M., & Cavalieri, M. B. (2009). Biologically costly altruism depends on emotional closeness among step but not half or full sibling. Evolutionary Psychology, 7, 118–132.

Carlson, M. J., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of multipartnered fertility among urban U.S. parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 718–732.

Carlson, M. J., & Meyer, D. R. (2014). Family complexity: Setting the stage. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 6–11.

Cherlin, A. J. (1978). Remarriage as an incomplete institution. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 634–650.

Cherlin, A. J., Kiernan, K. E., & Chase-Lansdale, P. L. (1995). Parental divorce in childhood and demographic outcomes in young adulthood. Demography, 32, 299–318.

Cherlin, A. J., & Seltzer, J. A. (2014). Family complexity, the family safety net, and public policy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 231–239.

Cooksey, E. C., & Fondell, M. M. (1996). Spending time with his kids: Effects of family structure on fathers’ and children’s lives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 693–707.

Cools, S., & Hart, R. K. (2017). The effect of childhood family size on fertility in adulthood: New evidence from IV estimation. Demography, 54, 23–44.

Diekmann, A., & Engelhardt, H. (1999). The social inheritance of divorce: Effects of parent’s family type in postwar Germany. American Sociological Review, 64, 783–793.

Diekmann, A., & Schmidheiny, K. (2013). The intergenerational transmission of divorce: A fifteen-country study with the fertility and family survey. Comparative Sociology, 12, 211–235.

D’Onofrio, B. M., & Lahey, B. B. (2010). Biosocial influences on the family: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 762–782.

Dronkers, J., & Härkönen, J. (2008). The intergenerational transmission of divorce in cross-national perspective: Results from the Fertility and Family Surveys. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 62, 273–288.

Evenhouse, E., & Reilly, S. (2004). A sibling study of stepchild well-being. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 248–276.

Feng, D., Giarrusso, R., Bengtson, V. L., & Frye, N. (1999). Intergenerational transmission of marital quality and marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 451–463.

Fomby, P., & Bosick, S. J. (2013). Family instability and the transition to adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 1266–1287.

Fomby, P., Musick, K., & Cross, C. J. (2018, April). Change in children’s family complexity and instability in the United States, 1970–2015. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Denver, CO.

Furstenberg, F. F. (2014). Fifty years of family change: From consensus to complexity. Annals of the American Association for the Political and Social Sciences, 654, 12–30.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., & King, R. B. (1999, April). Multipartnered fertility sequences: Documenting an alternative family form. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Chicago, IL.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., Levine, J. A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1990). The children of teenage mothers: Patterns of early childbearing in two generations. Family Planning Perspectives, 22, 54–61.

Ganong, L., & Coleman, M. (1988). Do mutual children cement bonds in stepfamilies? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 687–698.

Ganong, L., & Coleman, M. (2006). Patterns of exchange and intergenerational responsibilities after divorce and remarriage. Journal of Aging Studies, 20, 265–278.

Ginther, D., & Pollak, R. (2004). Family structure and children’s educational outcomes: Blended families, stylized facts, and descriptive regressions. Demography, 41, 671–696.

Glenn, N. D., & Kramer, K. B. (1987). The marriages and divorces of the children of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 811–825.

Gray, E., & Evans, A. (2008). The limitations of understanding multi-partner fertility in Australia. People and Place, 16(4), 1–8.

Guzzo, K. B. (2014). New partners, more kids: Multiple-partner fertility in the United States. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 66–86.

Guzzo, K. B., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (2007). Multipartner fertility among American men. Demography, 44, 583–601.

Halpern-Meekin, S., & Tach, L. (2008). Heterogeneity in two-parent families and adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 435–451.

Harcourt, K., Adler-Baeder, F., Erath, S., & Pettit, G. (2015). Examining family structure and half-sibling influence on adolescent well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 36, 250–272.

Härkönen, J., Bernardi, F., & Boertien, D. (2017). Family dynamics and child outcomes: An overview of research and open questions. European Journal of Population, 33, 163–184.

Hofferth, S. L. (2006). Residential father family type and child well-being: Investment versus selection. Demography, 43, 53–77.

Hofferth, S. L., & Anderson, K. G. (2003). Are all dads equal? Biology versus marriage as a basis for paternal investment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 213–232.

Hofferth, S. L., & Goldscheider, F. (2010). Family structure and the transition to early parenthood. Demography, 47, 415–437.

Högnäs, R. S., & Carlson, M. J. (2012). “Like parent, like child?”: The intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing. Social Science Research, 41, 1480–1494.

Holland, J. A., & Thomson, E. (2011). Stepfamily childbearing in Sweden: Quantum and tempo effects, 1950–99. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 65, 115–128.

Kahn, J. R., & Anderson, K. A. (1992). Intergenerational patterns of teenage fertility. Demography, 29, 39–57.

Kalmijn, M. (2015). Father-child relations after divorce in four European countries: Patterns and determinants. Comparative Population Studies, 40, 251–276.

Kalmijn, M., & Poortman, A.-R. (2006). His or her divorce? The gendered nature of divorce and its determinants. European Sociological Review, 22, 201–214.

Kohler, H.-P., Rodgers, J. L., & Christiansen, K. (1999). Is fertility behavior in our genes? Findings from a Danish twin study. Population and Development Review, 25, 253–288.

Kolk, M. (2014). Multigenerational transmission of family size in contemporary Sweden. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 68, 111–129.

Lappegård, T., & Rønsen, M. (2013). Socioeconomic differentials in multipartner fertility among Norwegian men. Demography, 50, 1135–1153.

Lappegård, T., Rønsen, M., & Skrede, K. (2011). Fatherhood and fertility. Fathering, 9, 103–120.

Lyngstad, T. H., & Engelhardt, H. (2009). The influence of offspring’s sex and age at parents’ divorce on the intergenerational transmission of divorce, Norwegian first marriages 1980–2003. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 63, 173–185.

Manning, W. D., Brown, S. L., & Sykes, J. B. (2014). Family complexity among children in the United States. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 48–65.

Manning, W. D., Smock, P. J., & Majumdar, D. (2004). The relative stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 135–159.

Marsiglio, W. (1992). Stepfathers with minor children living at home: Parenting perceptions and relationship quality. Journal of Family Issues, 13, 195–214.

McLanahan, S., & Bumpass, L. (1988). Intergenerational consequences of family disruption. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 130–152.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

Meyer, D. R., Cancian, M., & Cook, S. T. (2005). Multiple-partner fertility: Incidence and implications for child support policy. Social Service Review, 79, 577–601.

Murphy, M., & Knudsen, L. B. (2002). The intergenerational transmission of fertility in contemporary Denmark: The effects of number of siblings (full and half), birth order, and whether male or female. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 56, 235–248.

Murphy, M., & Wang, D. (2001). Family-level continuities in childbearing in low-fertility societies. European Journal of Population, 17, 75–96.

Pollet, T. V. (2007). Genetic relatedness and sibling relationship characteristics in a modern society. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 176–185.

Pope, H., & Mueller, C. W. (1976). The intergenerational transmission of marital instability: Comparisons by race and sex. Journal of Social Issues, 32(1), 49–66.

Raley, S., & Bianchi, S. (2006). Does gender of children matter? Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 401–421.

Riise, B. S., Dommermuth, L., & Lyngstad, T. H. (2016). Intergenerational transmission of timing of first birth in Norway. European Societies, 18, 47–69.

Rijken, A. J., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2009). Influences of the family of origin on the timing and quantum of fertility in the Netherlands. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 63, 71–85.

Rossi, A. S., & Rossi, P. H. (1990). Of human bonding: Parent-child relations across the life course. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Sobotka, T. (2008). Does persistent low fertility threaten the future of European populations? In J. Surkyn, P. Deboosere, & J. van Bavel (Eds.), Demographic challenges for the 21st century (pp. 27-89). Brussels, Belgium: VUB Press.

Statistics Sweden. (2013). Barnafödande i nya relationer [Having children in new relationships] (Demografiska Rapporter No. 2013:2). Stockholm, Sweden: Statistics Sweden, Forecast Institute.

Steenhof, L., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2008). Intergenerational transmission of age at first birth in the Netherlands for birth cohorts born between 1935 and 1984: Evidence from municipal registers. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 62, 69–84.

Stewart, S. (2005a). Boundary ambiguity in stepfamilies. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 1002–1029.

Stewart, S. (2005b). How the birth of a child affects involvement with stepchildren. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 461–473.

Strow, C., & Strow, B. (2008). Evidence that the presence of a half-sibling negatively impacts a child’s personal development. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67, 177–206.

Sundström, M. (2013). Growing up in a blended family or stepfamily: What is the impact on education? (SOFI Working Paper 2/2013). Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University.

Sweeney, M. (2007). Stepfather families and the emotional well-being of adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 33–49.

Tanskanen, A. O., & Danielsbacka, M. (2014). Genetic relatedness predicts contact frequencies with siblings, nieces and nephews: Results from the Generational Transmission in Finland Surveys. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 5–11.

Teachman, J. D. (2004). The childhood living arrangements of children and the characteristics of their marriages. Journal of Family Issues, 25, 86–111.

Thomson, E. (2014). Family complexity in Europe. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 245–258.

Thomson, E., Hanson, T. L., & McLanahan, S. S. (1994). Family structure and child well-being: Economic resources vs. parent socialization. Social Forces, 73, 221–242.

Thomson, E., Hoem, J. M., Vikat, A., Buber, I., Fuernkranz-Prskawetz, A., Toulemon, L., . . . Kantorova, V. (2002). Childbearing in stepfamilies: Whose parity counts? In E. Klijzing & M. Corijn (Eds.), Dynamics of fertility and partnership in Europe: Insights and lessons from comparative research (Vol. II, pp. 87–99). Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations.

Thomson, E., Lappegård, T., Carlson, M., Evans, A., & Gray, E. (2014). Childbearing across partnerships in Australia, the United States, Norway and Sweden. Demography, 51, 485–508.

Thomson, E., Mosley, J., Hanson, T. L., & McLanahan, S. S. (2001). Remarriage, cohabitation and changes in mothering. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 370–380.

Tillman, K. H. (2008a). Coresident sibling composition and the academic ability, expectations, and performance of youth. Sociological Perspectives, 51, 679–711.

Tillman, K. H. (2008b). “Non-traditional” siblings and the academic outcomes of adolescents. Social Science Research, 37, 88–108.

Turunen, J. (2014). Adolescent educational outcomes in blended families: Evidence from Swedish Register Data. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 55, 568–589.

Turunen, J., & Kolk, M. (2017, November). The prevalence of half-siblings over the demographic transition in Northern Sweden 1750–2007. Paper presented at the IUSSP International Population Conference, Cape Town, South Africa.

Vikat, A., Thomson, E., & Hoem, J. M. (1999). Stepfamily fertility in contemporary Sweden: The impact of childbearing before the current union. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 53, 211–225.

Washington, C. (2018, April). The effects of family structure transitions on young adults’ union instability. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Denver, CO.

White, L., & Riedmann, A. (1992). When the Brady Bunch grows up: Step/half- and fullsibling relationships in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 197–208.

Wolfinger, N. H. (1999). Trends in the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Demography, 36, 415–420.

Wolfinger, N. H. (2000). Beyond the intergenerational transmission of divorce: Do people replicate the patterns of marital instability they grew up with? Journal of Family Issues, 21, 1061–1086.

Wolfinger, N. H. (2005). Understanding the divorce cycle: The children of divorce in their own marriages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wolfinger, N. H. (2011). More evidence for trends in the intergenerational transmission of divorce: A completed cohort approach using data from the General Social Survey. Demography, 48, 581–592.

Wu, L. L. (1996). Effects of family instability, income, and income instability on the risk of a premarital birth. American Sociological Review, 61, 386–406.

Wu, L. L., & Martinson, B. C. (1993). Family structure and the risk of a premarital birth. American Sociological Review, 58, 210–232.

Zartler, U. (2011). Reassembling family ties after divorce. In E. Widmer & R. Jallinoja (Eds.), Families and kinship in contemporary Europe: Rules and practices of relatedness (pp. 178–191). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (202442/S20) and the Swedish Research Council through support for the Linneaeus Center for Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe (SPaDE) as well as by Stockholm University Demography Unit and Statistics Norway Research department. The register collection, Sweden in Time – Activities and Relations (STAR) is supported in part by grants from the Swedish Research Council. We are grateful for research assistance on the Swedish data from Jani Turunen. The findings and views reported in this article are those of the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lappegård, T., Thomson, E. Intergenerational Transmission of Multipartner Fertility. Demography 55, 2205–2228 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0727-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0727-y