Abstract

The effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) activities on corporate financial performance (CFP) could be linear or nonlinear. However, inconsistent results remain a research gap and thus need to be re-examined. By drawing on stakeholder theory and the neoclassical economics perspective while using the panel data of 155 Chinese listed firms from 2010 to 2020, system generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation results revealed an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP. Moreover, by drawing on the institutional-based view, it was determined that government subsidies moderate the inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP. Specifically, we found that the inverted U-shaped effect of ESG on CFP is weakened when government subsidies are high. This study contributes to the literature by confirming the presence of a curvilinear relationship between ESG and CFP. This study also generates meaningful implications suggesting that the governmental role in ESG is salient in mitigating associated financial costs for firms, thereby ultimately affecting CFP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Firms have increasingly engaged in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities to both maximize profitability and fulfill social goals. This has led to considerable interest in academia and practical considerations regarding firms that have embraced CSR principles (Barrena et al., 2016; Bhardwaj et al., 2018). For instance, the relationship between CSR and corporate financial performance (CFP) has been a longstanding topic in management studies (Lu et al., 2014; McWilliams & Siegel, 2000; Wang et al., 2016). Some studies have revealed a positive association between CSR and CFP, positing that the former could enhance firms’ reputations and competitive advantages (e.g., Kang et al., 2016; Wang & Choi, 2013). Others have argued that CSR could hurt CFP by imposing financial costs on firms (e.g., Smith & Sims, 1985; Wright & Ferris, 1997).

In recent years, firms have turned to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) activities as pillars of CSR, toward developing competitive advantages which could eventually affect their financial performance (Eccles & Serafeim, 2013). Following this trend, the topic of linkages between a firm’s ESG engagement and CFP has garnered attention in academia (Friede et al., 2015; Ortas et al., 2015). Similarly to assessments on CSR in general, studies have disagreed in their assessments on the effects of ESG on CFP, with some maintaining that ESG could improve CFP (e.g., Lo & Sheu, 2007; Rodriguez-Fernandez, 2016) and others identifying negative effects in ESG investment (e.g., Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Lee et al., 2016). At the same time, few studies have posed questions about or explored the possibility of U-shaped or inverted U-shaped relationships between ESG and CFP; such areas have remained underexplored (Sun et al., 2019).

Although the extant literature provides valuable insights, we have found several research gaps. First, previous studies have mostly examined the relationship between CSR and CFP (Lu et al., 2014; McWilliams & Siegel, 2000; Wang et al., 2016) rather than focusing on the effect of ESG on CFP. Although few nascent studies have investigated the relationship between ESG and CFP specifically, they display inconsistent results regarding this relationship (Bing & Li, 2019; Friede et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2019). In some studies, a short data period may be to blame for inconsistent results (Ruan and Liu, 2021), while the unique context of ESG in countries was not considered by others (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019). Moreover, the ESG-CFP relationship could be more complex than a simple linear relationship. However, the prior research has tended to simply assume a linear relationship between ESG and CFP. This assumption lacks sufficient supporting evidence and adequate consideration of a potential nonlinear relationship between ESG and CFP.

Second, few studies have explored how the unique context of emerging countries influences the relationship between ESG and CFP. Notably, existing studies have largely focused on developed countries (Buallay, 2019; Eliwa et al., 2021; Velte, 2017; Vishwanathan et al., 2020). However, the impact of ESG on CFP in emerging markets—where ESG initiatives are underdeveloped—remains far from clear (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019). Importantly, empirical evidence on the efficacy of ESG in developed countries cannot be generalized and applied to emerging countries (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2016; Ruan and Liu, 2021). Unlike developed countries, emerging countries are different in terms of having less favorable ESG cultures, lack of relevant initiatives, and poor business practices (Sharma & Sathish, 2022; Zhao et al., 2018). Therefore, the question of whether the involvement of ESG will improve CFP in emerging markets remains.

Third, although studies have investigated how CSR may increase or decrease CFP via micro and macro variables, insufficient number of studies have investigated the conditions under which the ESG-CFP relationship could be strengthened or weakened. The recent ESG literature has identified the moderating effects of multiple firm factors (Sun et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2015), while the roles of institutional factors have received little attention. Institutional determinants may significantly influence the ESG-CFP relationship since the institutional force is pivotal in driving ESG engagement and implementation—especially in emerging markets (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019). Relevant studies have argued that government subsidies, one of the essential institutional factors, are an effective incentive for firm social responsibility adoption and reap corporate benefits in the long run (Liu et al., 2019; Palmer et al., 1995; Porter & Van der Linde, 1995). However, the question of how and whether both ESG and government subsidies simultaneously affect CFP for firms is unexplored. Little attention has been paid to analyzing the combined effect of CFP on firms in emerging markets.

To address the aforementioned research gaps, this study attempts to find the accurately determine the relationship between ESG and CFP. Based on theoretical foundations, we hypothesize that an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP exists. An increasing number of studies have claimed that firms’ social responsibility has tended to be positive at the outset of ESG activities; however, after an inflection point, returns have tended to diminish and adversely affect CFP. Thus, by employing arguments from relevant studies, we posit whether a curvilinear relationship exists between ESG and CFP.

Furthermore, by drawing on the institutional-based view, we attempt to investigate whether government subsidies could moderate this relationship. The role of institutions has long been considered in CSR and CFP studies. For example, government support has tended to play a significant role in promoting CSR activities in emerging markets (Li et al., 2017). Following this logic, we consider whether government subsidies, as government support, could moderate the association between ESG and CFP.

To test our hypotheses, we examine Chinese firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges between 2010 and 2020. China is an ideal setting to highlight the unique context of emerging markets. Engaging in ESG creates additional cost burdens on administrative and human resources for Chinese firms (Ruan & Liu, 2021), which impair financial returns. Therefore, the question of whether engaging in ESG may improve CFP remains. To date, Chinese investors and firms cannot completely understand the effect of ESG on financial performance (Zhao et al., 2018). Furthermore, we choose China as our research setting because we aim to determine the actual roles of government. In China, firms engage in social-responsibility activities amid the government’s top-down interventionist approach (Wu et al., 2022). On the one hand, government coercion imposes costs when Chinese firms initiate ESG (Deng & Cheng, 2019; Dorfleitner et al., 2020) , while on the other, government subsidies are pervasive in China and tend to facilitate firms’ engagement in social-responsibility activities (Liu et al., 2019). Hence, the advantages and disadvantages of governmental roles coexist here.

This study makes two main theoretical contributions. First, it advances CSR studies, especially in disentangling the contradictory findings around ESG and its impact on CFP. Drawing upon stakeholder theory and neoclassical economics, we attempt to explain the circumstances in which ESG has positive or negative effects on CFP, and whether a curvilinear relationship exists. We expand upon limited studies on ESG to provide an in-depth understanding of the relationship between ESG and CFP.

Second, our study contributes to ESG studies by incorporating the theoretical underpinnings of the role of institutions in social responsibility. In particular, based on institutional theory, our study provides a holistic understanding of how institutional context and the role of government may shape ESG behaviors and outcomes in emerging countries. Since governments can facilitate CSR initiatives, our study empirically assesses whether government subsidies can moderate the ESG-CFP relationship. Hence, we generate theoretical implications to help understand how institutions could affect social responsibility in general, including ESG.

Literature review

ESG and CFP

ESG activities have tended to pertain to a firm’s management of natural resources, human rights, ethics, and community relationships (Aouadi & Marsat, 2018; Velte, 2017). Embodying the firm’s performance toward the goal of sustainable development, the “ESG score” has been closely linked to the company’s strengths, risks, and effectiveness (Almeyda & Darmansya, 2019). Hence, ESG has served as a measure of corporate culture and image, demonstrating to stakeholders and society the level of a firm’s commitment to sustainability (Buallay, 2019). In this regard, an increasing number of papers have come to argue that ESG activities could influence CFP (Dorfleitner et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2019).

We identified three main schools of thought on the relationship between ESG and CFP. The first school has tended to positively correlate ESG with CFP. Employing stakeholder theory, scholars under this tradition have argued that firms’ social-responsibility activities, such as ESG, could satisfy the interests of various shareholders, and ultimately increase CFP (Mohammad & Wasiuzzaman, 2021; Tarmuji et al., 2016). “Doing good while doing well,” a well-known CSR slogan, has typically been used to encapsulate the positive relationship between ESG and CFP (Mukherjee & Nuñez, 2019). It implies that firms engaging in social-responsibility activities such as ESG would be more attractive to potential stakeholders (Vishwanathan et al., 2020). ESG engagement would supposedly satisfy customers and job seekers looking for ways to identify with the firm’s image, culture, and future goals—all of which could reflect organizational commitment and enhance a firm’s reputation (Zhang et al., 2020). Also, a firm’s ESG engagement would be a testament to its willingness to allocate reasonable resources to maintain a sustainable relationship with stakeholders. This could help strengthen the firm’s access to critical stakeholder resources and create more long-term opportunities for client and business partnerships (Chedrawi et al., 2020). Therefore, engaging in ESG could attract attention and elicit confidence among stakeholders, thus bolstering firm reputation and customer satisfaction, as well as enhancing CFP (Yim et al., 2019).

Evidence of positive links between ESG and CFP is largely based on developed markets. Scholars have argued that ESG disclosure conveys better stakeholder engagement and transparency in a CSR environment, thereby increasing a firm’s competitive advantage (Buallay, 2019; Vishwanathan et al., 2020). Studies by Eliwa et al. (2021) and Velte (2017) also showed that ESG disclosure in developed markets tends to lower systemic market risk and idiosyncratic risk since it increases the transparency of information between investors and firms, thus leading to higher financial performance. Alareeni and Hamdan (2020) suggested that firms in counties where ESG disclosures are high (e.g., the US and European countries) tend to have high financial performance and competitive advantage through better firm reputation and customer satisfaction.

The second school of thought has subverted the above relationship to produce the slogan “doing good but not well” (Aouadi & Marsat, 2018; Hamilton et al., 1993). The neoclassical approach has argued that a firm’s main purpose would be to maximize its shareholders’ wealth, with any other non-financial objectives making a firm less effective; therefore, investing in ESG activities would create additional costs and hurt CFP (Friedman, 2007). According to this view, ESG activities beyond legal requirements, charitable donations, and measures to combat pollution, poverty, or unemployment would place undue financial burdens on firms (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001; Zhang & Guo, 2018). This school of thought has tended to portray ESG as an overinvestment (Ruan & Liu, 2021), which could lead to a competitive disadvantage and upset the stakeholders envisioning no benefits from the expenditure on ESG activities (Campbell, 2007; Farooq, 2015; Jia & Zhang, 2011). In transferring scarce resources away from the goal of maximizing shareholders’ wealth, ESG engagement could squeeze investments dry and consequently weaken CFP (Barnea & Rubin, 2010).

Numerous studies involving developing/emerging countries have found a negative association between ESG and CFP. They have largely argued that CSR activities are a far-reaching possibility in developing nations, highlighting a concern that overinvestment decisions for ESG initiatives and immature ESG environments in such countries would impair financial returns (Bing & Li, 2019; Sharma & Sathish, 2022). When ESG initiatives are in the initial stage, firms need to invest and adopt a series of ESG standards and requirements, which lowers their profits (Deng & Cheng, 2019). Bing and Li’s (2019) investigation of 1028 Chinese firms from 2010 to 2017 showed that ESG practices can harm a firm’s financial performance. This study provided evidence suggesting that engaging in CSR practices leads to more expenditures, thereby lowering a firm’s competitive advantage. From the context of the emerging market of Latin America, Duque-Grisales and Aguilera-Caracuel (2019) also provided empirical evidence suggesting that ESG is negatively associated with CFP. ESG activities lead to additional costs for a firm because they require investments in the improvement of products and processes to satisfy ESG requirements. Furthermore, this study also argued that the low legitimacy and low loyalty of firms in emerging countries generate image problems rather than improve firm reputation. Consequently, ESG suppresses the profit margins of emerging market firms.

The third and final school of thought has argued for a nonlinear relationship between ESG and CFP, associating concurrent positive and negative influences with it (Wang et al., 2008). During the early stages of ESG implementation, CFP could decline amid an increase in expenses. However, a higher level of firms’ social responsibility could enhance their value and display a competitive advantage to shareholders, increasing CFP and creating a U-shaped relationship (Chen et al., 2018; Trumpp & Guenther, 2017). In contrast, while ESG initiatives could help firms generate positive financial incomes, after an inflection point, they would likely become less attractive if shareholders were to perceive it as too much exposure. Increasing costs could also outweigh the advantages of ESG activities, creating an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP (Sun et al., 2019; Zhang & Guo, 2018).

ESG in China

In China, ESG initiatives started late and remained in the juvenile stage (Zhao et al., 2018). In December 2015, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange started the ESG initiatives and amended the “Guidelines for ESG Reporting.” When China introduced a green finance system in 2016 and started gaining momentum toward its 2060 goal of carbon neutrality, authorities started to require the disclosure of ESG information. Furthermore, in 2017 and 2019, the US Nasdaq Stock Exchange and European countries issued “ESG Reporting Guide 1.0 and 2.0,” which implemented the compliance of mandatory ESG activity disclosure (Ruan & Liu, 2021).

In line with shifts in international markets, the Chinese government continuously stressed the importance of ESG and improved related policies. In 2017, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) revised the “Listed Company Governance Guidelines” to require firms to disclose environmental information and social responsibility performance. In 2018, the CSRC revised the “Listed Company Governance Code,” stipulating that listed companies will have the responsibility to disclose ESG information.Footnote 1 The implementation of ESG is largely driven by policy incentives and regulation (i.e., using a top-down approach) to achieve high-quality societal development. In 2019, the Shanghai Stock Exchange mandated ESG-related information disclosure requirements, while the Hong Kong Exchange also required ESG information disclosure through the revision of “How to Prepare Environmental, Social and Governance Reports” (Ruan & Liu, 2021). As a result, in 2020, more than a quarter of A-share companies published annual ESG/CSR reports—compared to 371 Chinese listed firms in 2009.Footnote 2

Although China’s ESG information disclosure has leapfrogged, unlike developed economies where voluntary norms are voluntary and proactively implemented by firms (Almeyda & Darmansya, 2019), ESG remains a relatively new concept in China (Zhao et al., 2018). As previously noted, establishing the construction of ESG started late in China. Moreover, Chinese firms tend to consider ESG reporting as a future activity. Their lack of expertise and systems for ESG reporting has resulted in their slow development in this regard (Zhao et al., 2018). This may be because Chinese firms have not paid sufficient attention to ESG and there has been a lack of initiatives aimed to ensure the objectiveness of ESG information disclosure (Ruan & Liu, 2021). Chinese firms largely recognize that ESG/CSR activities may improve a firm’s reputation and brand image while also feeling that a firm’s ratings on non-accounting indicators suggest how risk is controlled (Alareeni & Hamdan, 2020). Therefore, firms believe that ESG disclosure could aggravate the information asymmetry between investors and firms (Ruan & Liu, 2021), and investors and firms in China do not ascribe enough importance to ESG.

Moreover, many in China doubt whether engaging in ESG activities yields benefits. To settle the ESG practices, Chinese authorities mandated that Chinese firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Exchanges must report ESG activities to meet global standards. This top-down approach from the Chinese government has prompted Chinese firms to add independent directors, replace obsolete equipment with greener technology, and invest in systems for streamlined data collection procedures and monitoring systems to meet the regulatory requirements of ESG information disclosure (Cui et al., 2021). Therefore, achieving compliance in this regard has created additional cost burdens for companies (Ruan & Liu, 2021). Hence, the government’s pressure on firms to initiate ESG imposes direct costs on firms (Duque-Grisales and Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019). As such, firms that adopt ESG practices must cope with increased stress regarding financial performance and are at a competitive disadvantage over those who do not engage in ESG practices (Bing & Li, 2019; Wang et al., 2008).

Furthermore, the lack of trust in and loyalty toward ESG among Chinese stakeholders has forced firms to invest more in ESG, thereby imposing costs on the firms. Despite the endeavors made to develop initiatives on ESG, emerging market firms have not yet earned sufficient trust and loyalty from their workers, consumers, and society in general (Reimann et al., 2012). A lack of trust is caused by corruption, unclear information disclosure, and low degrees of investor protection. To demonstrate greater legitimacy in questions relevant to its stakeholders, Chinese firms must invest more in corporate governance mechanisms (i.e., hiring external auditors), which imposes high expenses on Chinese firms (Ruan & Liu, 2021).

Taken together, the question that remains is whether the involvement of ESG will positively influence a firm’s performance in China. Due to institutional conditions and the discrepancy between perceptions and practices, investors and firms in China cannot clearly understand neither the specific impact of ESG practices on firm performance nor the contingent determinants between the link. Only a few studies have attempted to answer this question (c.f., Deng & Cheng, 2019). Therefore, at this time, it is vital to provide the theoretical and practical implications of the value of ESG on CFP.

Hypotheses development

Curvilinear relationship between ESG and CFP

Our discussion thus far has proposed that the relationship between ESG and CFP is more complex than in the aforementioned studies’ bipolar views (Aouadi & Marsat, 2018; Buallay, 2019; Dorfleitner et al., 2020). In particular, the relationship could be more complicated when ESG practices are not conducted in the effective manner (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019). By analyzing the likely trends around the specific benefits and costs of ESG and integrating these opposing effects, we posit an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP.

As previously noted, adopting a standard certification and endeavors associated with ESG activities helps to strengthen the sustainable relationship with stakeholders by conveying quality information, creating more opportunities with stakeholders, strengthening the firm’s legitimacy, and distinguishing its capability from competitors (Su et al., 2016). A good ESG record can positively impact a firm’s reputation and brand image. Thus, such positive links help improve CFP (Yim et al., 2019). However, increases in benefits (i.e., the slope of the curve for the total benefits of ESG) would be expected to gradually level off for several reasons (Wang et al., 2008).

First, despite stakeholders’ willingness to support ESG initiatives, there are limits to the amount and type of resources that socially conscientious stakeholders could control and thus potentially provide to the firm. These limitations have tended to place a natural ceiling on the amount of benefits a firm could obtain from voluntary activities, including ESG (Zhang et al., 2018). Second, and perhaps more importantly, even if we were to assume that stakeholders would be able to provide unlimited resources, a constant linear relationship would be highly unlikely. In subscribing to the traditional perspective of neoclassical economics, one encounters a trade-off between ESG and CFP. From this perspective, if social-responsibility activities were to run counter to the pursuit of profit maximization for shareholders, the firm would suffer losses (Friedman, 2007).

Social-responsibility activities have tended to raise direct costs and thus affect CFP (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001). This could extend to investments in ESG, specifically: For instance, a firm could find it necessary to establish a separate department devoted to ESG if considerably raising its engagement in it. Such commitment would likely increase the firm’s overall human resources and administrative costs (Wang et al., 2016). Furthermore, a firm would be expected to spend heavily to complete its transformation, including upgrading its operations and products (Palmer et al., 1995).

The additional costs from such initiatives could suppress financial performance since corporate funds would be compromised (Ruan & Liu, 2021). These higher direct costs could further impair CFP by making the firm less attractive to stakeholders (Aouadi & Marsat, 2018). As also mentioned earlier, expenditures on ESG activities could be seen as a drain on resources without any financial return (Hillman & Keim, 2001). Therefore, stakeholders might regard the firm as overspending on activities beyond the core business, and thus less profitable. At a certain point, maintaining high ESG-related costs could no longer be justified, as such activities have been found to eventually stop delivering an acceptable level of added value (Sun et al., 2019).

Taken together, these countervailing forces should lead to an inverted U-shaped, curvilinear relationship between ESG and CFP. Within certain limits, ESG initiatives could help a firm enhance its reputation, elicit stakeholder support, secure essential resources, and provide protections against the risk of resource loss (Godfrey, 2005; Vishwanathan et al., 2020). However, if ESG activities were to increase beyond a certain level, their positive effects would likely level off due to increased direct costs and resource control by stakeholders (Hillman & Keim, 2001; Wang et al., 2008). Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H1. ESG and CFP will have an inverted U-shaped relationship.

Moderating role of government subsidies

Compared to developed countries, firms in emerging markets with underdeveloped social responsibility mechanisms are normally influenced by state intervention (Wang et al., 2008). The driver of CSR initiatives would be supports from related legislation and regulations, with the government demonstrating a strong commitment to social responsibility through varying policies. These measures can entail stringent command-and-control regulations, including penalties and fines, while also providing voluntary incentives such as economic incentives and subsidies (Wu et al., 2022). For instance, since firm’s voluntary program and strategy are undeveloped in China, its government is a central actor in both establishing legislation and pursuing societal development (Cui et al., 2021). Therefore, the government plays a more strategic role in providing impetus by harnessing related laws and regulations.

Studies from the institutional-based approach have long argued that government regulations could promote firms’ social-responsibility engagement and implementation (Kim et al., 2013; Vallentin, 2015). Regulators, including those involved in reporting and policy enforcement, have tended to raise awareness of social responsibility, provide guidelines for procurement, and improve transparency and voluntary disclosures (Dorobantu et al., 2017). In doing so, regulatory institutions could shape firms’ social-responsibility behaviors and outcomes by engaging in the societal goals around sustainable development (Jamali et al., 2020). If firms were to adopt a flexible, laissez-faire approach or facilitate voluntary codes on social responsibility issues, the government could step in and act as an impactful “push variable,” providing guidelines and policies to facilitate ESG engagement (Marquis & Qian, 2014).

According to Albareda et al. (2007), government roles in fostering firms’ social responsibility have been to mandate (“command-and-control” legislation) and facilitate (policies, fiscal funding, and support to create incentives). Governments launch legal instruments, including laws and regulations, to encourage firms to embrace social responsibility. Such legislative power often requires disclosures from firms. “Command-and-control,” as the term suggests, tends to be compulsory. Thus, the government could compel firms to conduct social-responsibility activities by urging them to comply with directives and regulations and monitoring auditing and reporting systems (Škare & Golja, 2014; Zhang et al., 2018).

Governments could also provide economic incentives such as tax breaks, financial support, and other subsidies to persuade firms to engage in social responsibility (Bradly & Nathan, 2019). Such a market-based system has tended to be flexible, incentivizing firms to voluntarily adopt social responsibility and creating a self-reinforcing mechanism, unlike coercive measures like compulsory government intervention (Sarker, 2013). Therefore, neoclassical economists have long argued for less government intervention and more of a market-based incentive system, claiming that firms allowed to voluntarily participate in social responsibility would be incentivized to reap the benefits in the long run (Palmer et al., 1995; Porter & Van der Linde, 1995).

Government subsidies have been regarded as the most effective type of public incentive for social responsibility adoption (Qi et al., 2021). Firms receiving government subsidies have tended to be more willing to initiate social-responsibility activities toward realizing societal goals (Liu et al., 2019). This has included proactive engagement in charity and environmental protection to address related political pressures (Qi et al., 2021).

Since ESG activities have clearly been costly, government subsidies may relieve the pressure on cash flow and financial resources (Deng et al., 2020; Marquis & Qian, 2014) and provide solutions to cost-related financial constraints as well as improve product efficiency, which could lead firm to continuous ESG (Liu et al., 2019). Therefore, governments hold the power to mitigate the additional cost burden from social responsibility: After obtaining government subsidies, firms may have sufficient financial slack to engage in ESG activities.

Firms with higher government subsidies could channel them into making ESG activities more efficient and be more flexible in choosing how to enhance their ESG abilities (Marquis & Qian, 2014). Firms armed with government subsidies might more proactively adopt ESG initiatives by, for instance, upgrading to green technology and developing eco-friendly products (Li et al., 2018). Such companies would then be positioned to inform stakeholders of their ESG activities (Su et al., 2016). Such reinforcement could also reduce costs since stakeholders could come to perceive ESG as a valuable pursuit; their greater commitment would, in turn, potentially bolster competitive advantage and reputation (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019). With these considerations, we hypothesize thus:

-

H2. Government subsidies will moderate (flatten) the inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP. Specifically, the effect of this inverted U-shape is strengthened for firms with lower government subsidies.

Methodology

Data collection

ESG activities have been considered crucial since the term ESG was introduced in 2005 (Almeyda & Darmansya, 2019). The databases of Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters started to provide firm ESG scores in 2008 by developing in-house ESG expertise (Tarmuji et al., 2016). However, ESG information disclosure is concentrated on the firms of developed economies. Latecomers to ESG initiatives in developing/emerging markets, including those in China, have a more limited number of available ESG scores (Alareeni & Hamdan, 2020). The collection of Chinese firms’ ESG scores became feasible around 2010 (Deng & Cheng, 2019). Thus, extant studies on ESG in China were conducted after 2010 (Bing & Li, 2019; Garcia et al., 2017; Ruan & Liu, 2021).

Accordingly, we collected data on Chinese A-share companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2010 to 2020. To collect ESG scores, we used Datastream software provided by Thomson Reuters. We combined the China Stock Market Accounting Research Data Service (CSMAR, https://cn.gtadata.com) database with the annual reports of each company from the WIND database (https://www.wind.com.cn) to collect government support information and other firm-related variables. After adopting a 1-year lag and deleting missing data, we obtained unbalanced panel data from 155 firms. The final sample consists of 355 observations.

Measures

ESG

The Thomson Reuters Eikon database provides a firm’s total ESG score, which is the combined ESG performance value of three subgroups: environmental (E score), social (S score), and governance (G score) (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019; Taylor et al., 2018). The environmental dimension pertains to resource use “reduction, emission reduction, and product innovation”; the social dimension to “human rights, workforce opportunities, society and community, training and development, product responsibility, employment quality, and health and safety”; and the governance dimension to “vision and strategy, shareholder rights, board functions, board structure, and compensation policy”. The value ranges from 0 to 100. The higher the combined value of ESG, the higher the ESG score.

CFP

We used the return on assets (ROA) ratio to measure CFP, which is net income divided by total assets (Fisher & McGowan, 1983; Hillman & Keim, 2001). Relevant studies on ESG-CFP argued that CFP could be estimated on accounting- or market-based measures (c.f., Atan et al., 2018). In this study, we used accounting-based measures rather than market-based measures because the accounting-based measures could provide more appropriate information in a “transaction economy” such as China’s, where the capital market is not perfectly competitive (Velte, 2017). We used ROA—a proxy of accounting-based measurement—because it is the most commonly used measure to evaluate firms’ financial performance (Hambrick & Quigley, 2014; Waddock & Graves, 1997).

Government subsidies

For this study, a government subsidy refers to a free monetary allocation (not including government capital investments) (Deng et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). We obtained government subsidies and reward figures for firms’ ESG activities from CSMAR and the annual reports of each company. Following the study of Jiang et al. (2020), to measure ESG-related government subsidies, we first obtained a firm’s total subsidies received from central and local governments. We then carefully screened the specifications of the subsidies and subtracted those unrelated to ESG from the totals. For example, government subsidies for environmental protection and renewable energy were among those included in this study. We used natural logarithm of the value of government subsidies to correct for its skewness (Deng et al., 2020).

Control variables

Based on previous studies’ frameworks, five firm-level variables were controlled for, due to their potential impact on a firm’s financial performance. These were namely firm size, firm age, debt ratio, growth ratio, and R&D intensity. Firm size was measured according to the natural logarithm of the company’s total assets, to control for the effect of economies of scale on ESG activities and firm performance (Orlitzky, 2001). Since a company’s performance can be dependent on its accumulated experience, we added firm age and past financial index to control for the effect of accumulated experience and financial conditions on its performance (Wang & Choi, 2013). Firm age was the number of years since the firm’s establishment; debt ratio was the firm’s total debt over its total assets; growth ratio was the percentage increase of the firm’s total sales; and R&D intensity was the ratio of R&D expenditures to the firm’s total sales. Finally, at the industry level, we controlled for competitive intensity, calculated by subtracting the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) from 1 (Deng et al., 2020).

Estimation methodology

Given that our data comprise both cross-sectional and time-series data, this study employs panel data estimation. We set out to consider the presence of latent unobservable effects for each firm. Moreover, we use an instrumental variable approach to address potential endogeneity problems, namely the system GMM (generalized method of moments) estimator (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). The system GMM estimator addresses simultaneity biases and endogeneity problems by using first-difference estimators as instrumental variables.

This study employed three tests to ensure the reliability and validity of the system GMM estimator (Roodman, 2009). For the Sargan and Hansen tests, not all instruments were related to the dependent variable, which implies the validity of all instruments. Additionally, for the second-order autocorrelation test, there was no absence of the second autocorrelation for the error term. We estimated the system GMM by applying STATA15.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among all variables. Before testing our hypotheses, we tested the multicollinearity among variables. We verified that the highest value of VIF was 1.26. As this turned out to be significantly lower than the acceptable value of 10, it appeared that multicollinearity was not a major concern for our study (Hair et al., 2010).

Table 2 displays the results from system GMM estimation. We included the independent variable in model 1 and the independent and control variables in model 2. Model 3 tested hypothesis 1 (H1). Model 4 included the moderating variable to test hypothesis 2 (H2).

As shown in model 2, the coefficient of ESG scores was positive, but not statistically significant (\(\beta =0.001\), n.s.). In model 3, the coefficient of ESG scores was positive, the coefficient of the square term of ESG scores was negative, and both of them became statistically significant (\(\beta =0.008\), \(p=0.008\); \(\beta =-0.004\), \(p<0.001\), respectively). The latter confirms the inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP, supporting H1. Finally, in model 4, the interaction between the squared term for ESG and government subsidies was positive and statistically significant (\(\beta =0.001\), \(p<0.05\)), supporting H2.

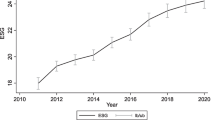

To gain further insights into the moderating effects of government subsidies, we plotted the results from model 4. Figure 1 depicts the effects of ESG and government subsidies on CFP, indicating that the inverted U-shaped relationship changes as government subsidies increase. This finding suggests that government subsidies moderate the effects of an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG on CFP. The relative slopes of the graphs at low, middle, and high government subsidy levels further confirm these findings: The figure demonstrates that the relationship between ESG and CFP within the high government subsidy curve is flatter than the relationship within the low government subsidy curve.

Conclusion

This study examined the associated ESG and CFP of 155 Chinese listed firms on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2010 to 2020. We began by investigating the relationship between ESG and CFP and found it to have an inverted U-shaped relationship. We also found that government subsidies appeared to flatten this relationship. As we had hypothesized and shown in Fig. 1, the inverted U-shape effect of ESG on CFP appeared weaken for firms with more government subsidies. Based on our findings, we present the following theoretical implications for relevant fields of study.

Theoretical implications

Our study makes several contributions to our understanding of ESG and CFP in general. First, it provides detailed arguments and empirical support for a curvilinear relationship between ESG and CFP. Therefore, our study contributes to both management studies and CSR studies. The existing CSR studies have focused on the simple linear relationship between ESG and CFP, rather than exploring its complexity. Unlike extant studies, our research has managed to prove the presence of a curvilinear relationship between ESG and CFP. We articulate this process in detail, drawing from and integrating stakeholder theory and neoclassical economics. Even with respect to ESG and CFP in general, we are aware of only a handful of studies—including Sun et al. (2019), Wang et al. (2008), and Zhang and Guo (2018)—which have alluded to the possibility of a curvilinear relationship.

Our findings imply that while ESG activities may positively influence CFP, after a certain point, ESG is likely to hurt CFP by imposing financial costs, which could eventually become intolerable to firms. Our results are consistent with the arguments of Sun et al. (2019) and Wang et al. (2008). Although ESG engagement may arise from stakeholders’ support, complex circumstances may adversely influence CFP. Our research calls for caution regarding how to consider ESG costs when evaluating firm performance. In this regard, not only have we provided detailed theoretical foundations, but also empirical support for a curvilinear ESG–CFP relationship.

Second, we enrich the theoretical underpinnings of ESG by identifying the related mechanism in further detail, in examining the moderating effects of government subsidies on the ESG–CFP relationship. While institutional-based perspectives have tended to portray political instruments as pronounced catalysts for ESG activities (Dorobantu et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2013), previous studies did not sufficiently discuss the mechanism through which the circumstances of policy instruments could affect ESG and CFP (Qi et al., 2021). Our results indicate that government subsidies can flatten an inverted U-shaped relationship between ESG and CFP, meaning that governmental subsidies can mitigate the direct financial costs originating from ESG initiatives. This may be related to firms’ perception of government subsidies as financial resources; the larger the amount, the better the chance of relief from ESG-related costs.

Our findings are in line with the tenet of the institutional-based approach that CSR effectiveness may be dependent on institutional context (Kim et al., 2013; Vallentin, 2015). The results of the present study imply that policy instruments may mitigate the pressure of financial costs and facilitate social-responsibility engagement, affecting the firm’s financial performance. By building a more comprehensive outlook, our research marks an attempt to examine how government subsidies moderate the ESG–CFP relationship, complementing CSR studies and also capturing a more complete picture of ESG.

In this regard, our study differs from extant studies by demonstrating the institutional context and government role in ESG-CFP. Traditionally, studies of ESG have not investigated the interaction between policy instruments and ESG (Cui et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2015). Given the importance of both regulatory instruments and ESG to firms, combining them produces valuable insights into understanding the essential drivers of firm performance (Marquis & Qian, 2014). Our study suggests that ESG represents endeavors that link societal goals with its external environments, and the institutional environment indicates more than conditions that influence financial outcomes. From this perspective, the integration of two theoretical rationales—CSR and the institutional-based perspective—embodies a new vision of firm traits, such that institutions affect ESG activities in a way that sustains engagement in social responsibility.

Our study also hints at which policy instruments may benefit the ESG-CFP relationship. Relevant studies have long discussed how and which two contradictory types of regulations—command-and-control regulation vs. the market-based regulatory approach—affect the CSR behaviors and outcomes (Albareda et al., 2007; Palmer et al., 1995; Porter & Van der Linde, 1995). The former is coercive (e.g., via fines and sales bans), while the latter emphasizes voluntary good behavior and self-determination with flexible instruments (e.g., subsidies and tax incentives) (Sarker, 2013; Zhang et al., 2018).

Some argue that solid government intervention and punitive measures via command-and-control regulation are more effective in supporting CSR activities (Albareda et al., 2007; Škare & Golja, 2014). Other studies argue that voluntary norms that serve as market-based incentives are better because flexible instruments are proactively fulfilling the expectation of society by motivating firms via a bottom-up approach (Bradly & Nathan, 2019; Palmer et al., 1995). Our findings illustrate that market-based incentives may be effective and also suitable as regulative measures for driving a firm’s ESG engagement. Although costs related to ESG activities may impair a firm’s financial performance, by obtaining government subsidies, firms could continue social responsibility activities by mitigating the pressure of financial burdens. Our findings can help compile in-depth knowledge regarding the role of government in ESG engagement.

Lastly, our study advances ESG studies by illustrating the ESG-related circumstances of an emerging economy. “Doing well by doing good” has been the standard motto in explaining the role of ESG on CFP (Vishwanathan et al., 2020). However, our research shows that ESG maturity can affect CFP in an emerging economy. Very few studies have considered how the institutional context of countries may shape the maturity of ESG (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2019; Garcia et al., 2017). Relevant studies have largely treated institutional context as the background (Bing & Li, 2019; Zhao et al., 2018), while the impact of such circumstances on the ESG-CFP relationship has been neglected.

By providing detailed circumstances of an exogenous environment in an emerging market such as China, our study suggests that institutional context may influence the maturity of ESG. Furthermore, our results reveal that immature ESG circumstances may foment critical cost burdens to firms engaging in ESG activities in the emerging market context. Thus, this study addresses the research gap with respect to what has been explored in the previous CSR/ESG studies in the context of emerging economies. Our study illustrates that firms in emerging economies may experience different stages of ESG maturity; therefore, previous findings on the ESG-CFP cannot be generalized to emerging markets due to heterogeneous institutional conditions. In this sense, our findings hint at the factors and underlying mechanisms that firms in emerging economies should understand when deploying ESG into strategic decisions. This study incorporated meaningful variables that can illuminate the complexity of ESG, thereby offering in-depth knowledge.

Managerial implications

Our study also carries practical implications for managers and policymakers, as more firms become eager to engage in ESG. Companies have increasingly recognized ESG as a means to enhance competitive advantage, and as a win–win strategy to fulfill societal goals and boost their own performance. At the same time, managers must realize that ESG activities inevitably consume financial resources, such as investments in human resources and green facilities (Ruan & Liu, 2021). An acceptable rate of return on such investments may become elusive after a certain point. Therefore, managers ought to weigh the potential benefits of ESG against the expenditures necessary for ESG activities.

In addition, policymakers in emerging economies, where ESG tends to be less mature, ought to be aware that regulatory means could help drive ESG at the national level. Economic incentives and government subsidies to firms can steer the latter into fulfilling societal goals (Sarker, 2013). Therefore, regulatory authorities ought to more proactively work on creating a system of incentives. The Chinese government, for instance, provides environmental subsidies to promote green innovation and combat pollution, but fewer subsidies to address social- and governance-related concerns. It has long been argued that a “command-and-control” regulatory system has been more effective in driving social responsibility, since, unlike a flexible, market-based incentive system, it demands action (Škare & Golja, 2014). However, Chinese policymakers ought to realize that a market-based system involving government subsidies may bring benefits by reducing pressure on firms’ cash flow, thus driving ESG initiatives. Therefore, more consideration of ESG-related options is needed in China.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Although this study provides several theoretical and managerial implications, it has certain limitations. For example, the ESG—the object of the sample selection—was obtained only from Chinese firms. Parameters among the firms selected constitute another limitation: All the firms in the sample were listed on China’s stock market exchanges, meaning that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) which were not publicly listed were excluded. Moreover, since all the firms had to be in sound financial condition to be included in the sample, firms with poor ESG and financial weaknesses did not make the cut, either. Future research should expand the sample to such companies, so that analyses of the effects of ESG on financial performance become generalizable.

Furthermore, since we only used Chinese firms, our sample may give the limited knowledge about more developed country context. Hence, future research should consider a larger sample of firms from diverse countries to improve the generalizability of the results. In particular, a comparative study between developing and developed economies can be conducted to examine the ESG circumstances of different countries (Kulshreshtha et al., 2019).

There may be a time lag in the effects of ESG. Based on our findings, increases in profitability after investing in ESG seem to be inferior to the total expenditures on it, at least in the short run (i.e., 1 year in this study). However, if the term under analysis were to be lengthened, the findings on investments in ESG could be different. Considering the recent rise in ESG activities among Chinese firms, further studies are necessary to gain insights into the effects such initiatives could exert on CFP in the long run.

This study also did not analyze various indicators of CFP to ESG. We used ROA to represent CFP, the variables most commonly used for analysis in prior research. We did not include a detailed exploration of how other indicators of CFP (e.g., Tobin’s Q, PE, EVA) could be related to ESG. Further research could examine the various CFP indicators in light of ESG initiatives. Also, for ESG, we used the secondary data of ESG scores provided by Thomson Reuters. Although these data have been widely used in recent literature (Bing & Li, 2019; Garcia et al., 2017; Ruan & Liu, 2021; Tarmuji et al., 2016), the evaluation method of ESG scores could be subjective according to the database companies, which may influence the results of our study. Recently, local database companies have also provided ESG scores by developing evaluation methods and hiring experts (Bing & Li, 2019). Such measurements could also be reliably to reflect the local circumstances of ESG. Thus, future studies should consider other alternative measures of ESG scores, such as interviews and survey data from local database companies.

As a final consideration, our paper addresses the important question of whether policy instruments may influence the ESG-CFP relationship. To address the impact of government role on ESG-CFP in this study, we only examined voluntary norms (i.e., government subsidies). As previously noted, two different types of regulations—command-and-control regulations and voluntary norms—can have varying impacts on the ESG-CFP relationship (Qi et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2015). Hence, the future studies should compare and identify which policy instruments flatten and steepen the ESG-CFP relationship. In this manner, a more comprehensive picture of government roles can be drawn to fortify the results of academics and guide policymakers.

Notes

China Briefing, What is ESG Reporting and Why is it Gaining Traction in China? https://www.china-briefing.com/news/what-is-esg-reporting-and-why-is-it-gaining-traction-in-china/ (accessed July 28, 2022).

Capital Monitor, China’s new ESG disclosure standard “of limited use” to investors, https://capitalmonitor.ai/regions/asia/china-esg-disclosure-standard-investors/ (accessed July 28, 2022).

References

Alareeni, B. A., & Hamdan, A. (2020). ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society.

Albareda, L., Lozano, J. M., & Ysa, T. (2007). Public policies on corporate social responsibility: The role of governments in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 391–407.

Almeyda, R., & Darmansya, A. (2019). The Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure on Firm Financial Performance. IPTEK Journal of Proceedings Series, 5, 278–290.

Aouadi, A., & Marsat, S. (2018). Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 1027–1047.

Arellano, M., & Bover, S. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-component models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51.

Atan, R., Alam, M. M., Said, J., & Zamri, M. (2018). The impacts of environmental, social, and governance factors on firm performance: Panel study of Malaysian companies. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal.

Barnea, A., & Rubin, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 71–86.

Barrena, J., López, M., & Romero, P. M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25(1), 8–14.

Bhardwaj, P., Chatterjee, P., Demir, K. D., & Turut, O. (2018). When and how is corporate social responsibility profitable? Journal of Business Research, 84(3), 206–219.

Bing, T., & Li, M. (2019). Does CSR signal the firm value? Evidence from China. Sustainability, 11(15), 4255.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bradly, A., & Nathan, G. (2019). Institutional CSR: Provision of public goods in developing economies. Social Responsibility Journal, 15(7), 874–887.

Branco, M. C., & Rodrigues, L. L. (2008). Social responsibility disclosure: A study of proxies for the public visibility of Portuguese banks. The British Accounting Review, 40(2), 161–181.

Buallay, A. (2019). Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 30(1), 98–115.

Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967.

Capital Monitor, China’s new ESG disclosure standard “of limited use” to investors, https://capitalmonitor.ai/regions/asia/china-esg-disclosure-standard-investors/ (accessed July 28, 2022)

Chedrawi, C., Osta, A., & Osta, S. (2020). CSR in the Lebanese banking sector: A neo-institutional approach to stakeholders’ legitimacy. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 14(2), 143–157.

Chen, C. J., Guo, R. S., Hsiao, Y. C., & Chen, K. L. (2018). How business strategy in non-financial firms moderates the curvilinear effects of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility on corporate financial performance. Journal of Business Research, 92, 154–167.

China Briefing, What is ESG reporting and why is it gaining traction in China? https://www.china-briefing.com/news/what-is-esg-reporting-and-why-is-it-gaining-traction-in-china/ (accessed July 28, 2022)

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2016). Multilatinas as sources of new research insights: The learning and escape drivers of international expansion. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 1963–1972.

Cui, Y., Khan, S. U., Li, Z., & Zhao, M. (2021). Environmental effect, price subsidy and financial performance: Evidence from Chinese new energy enterprises. Energy Policy, 149, 112050.

Deng, X., & Cheng, X. (2019). Can ESG indices improve the enterprises’ stock market performance?—An empirical study from China. Sustainability, 11(17), 4765.

Deng, X., Long, X., Schuler, D. A., Luo, H., & Zhao, X. (2020). External corporate social responsibility and labor productivity: A S-curve relationship and the moderating role of internal CSR and government subsidy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 393–408.

Dorfleitner, G., Kreuzer, C., & Sparrer, C. (2020). ESG controversies and controversial ESG: About silent saints and small sinners. Journal of Asset Management, 21(5), 393–412.

Dorobantu, S., Kaul, A., & Zelner, B. (2017). Nonmarket strategy research through the lens of new institutional economics: An integrative review and future directions. Strategic Management Journal, 38(1), 114–140.

Duque-Grisales, E., & Aguilera-Caracuel, J. (2019). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of Multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. Journal of Business Ethics, 168(2), 315–334.

Eccles, R. G., & Serafeim, G. (2013). The performance frontier: Innovating for a sustainable strategy: Interaction. Harvard Business Review, 91(7), 17–18.

Eliwa, Y., Aboud, A., & Saleh, A. (2021). ESG practices and the cost of debt: Evidence from EU countries. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 79, 102097.

Farooq, O. (2015). Financial centers and the relationship between ESG disclosure and firm performance: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Applied Business Research, 31(4), 1239–1244.

Fisher, F. M., & McGowan, J. J. (1983). On the misuse of accounting rates of return to infer monopoly profits. American Economic Review, 73(1), 82–97.

Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233.

Friedman, M. (2007). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In Corporate ethics and corporate governance (173–178). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Garcia, A. S., Mendes-Da-Silva, W., & Orsato, R. J. (2017). Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 150, 135–147.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Harlow: Pearson.

Hambrick, D. C., & Quigley, T. J. (2014). Toward more accurate contextualization of the CEO effect on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 35(4), 473–491.

Hamilton, S., Jo, H., & Statman, M. (1993). Doing well while doing good? The investment performance of socially responsible mutual funds. Financial Analysts Journal, 49(6), 62–66.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–139.

Jamali, D., Jain, T., Samara, G., & Zoghbi, E. (2020). How institutions affect CSR practices in the Middle East and North Africa: A critical review. Journal of World Business, 55(5), 101127.

Jia, M., & Zhang, Z. (2011). Agency costs and corporate philanthropic disaster response: The moderating role of women on two-tier boards–evidence from People’s Republic of China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(9), 2011–2031.

Jiang, Z., Wang, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2020). Can voluntary environmental regulation promote corporate technological innovation? Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(2), 390–406.

Kang, C., Germann, F., & Grewal, R. (2016). Washing away your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility, and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 80(2), 59–79.

Kim, C. H., Amaeshi, K., Harris, S., & Suh, C. J. (2013). CSR and the national institutional context: The case of South Korea. Journal of Business Research, 66(12), 2581–2591.

Kulshreshtha, K., Bajpai, N., Tripathi, V., & Sharma, G. (2019). Cause-related marketing: an exploration of new avenues through conjoint analysis. Benchmarking: An International Journal.

Lee, K. H., Cin, B. C., & Lee, E. Y. (2016). Environmental responsibility and firm performance: The application of an environmental, social and governance model. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(1), 40–53.

Li, D., Cao, C., Zhang, L., Chen, X., Ren, S., & Zhao, Y. (2017). Effects of corporate environmental responsibility on financial performance: The moderating role of government regulation and organizational slack. Journal of Cleaner Production, 166, 1323–1334.

Li, Z., Liao, G., Wang, Z., & Huang, Z. (2018). Green loan and subsidy for promoting clean production innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 187, 421–431.

Liu, Y., Quan, B. T., Xu, Q., & Forrest, J. Y. L. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and decision analysis in a supply chain through government subsidy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 208, 436–447.

Liu, J. J., Zhao, M., & Wang, Y. (2020). Impacts of government subsidies and environmental regulations on green process innovation: A nonlinear approach. Technology in Society, 63, 101417.

Lo, S., & Sheu, H. (2007). Is corporate sustainability a value-increasing strategy for business? Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(2), 345–358.

Lu, W., Chau, K. W., Wang, H., & Pan, W. (2014). A decade’s debate on the nexus between corporate social and corporate financial performance: A critical review of empirical studies 2002–2011. Journal of Cleaner Production, 79, 195–206.

Marquis, C., & Qian, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organization Science, 25(1), 127–148.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2000). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 603–609.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

Mohammad, W. M. W., & Wasiuzzaman, S. (2021). Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosure, competitive advantage and performance of firms in Malaysia. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 2, 1–11.

Mukherjee, A., & Nuñez, R. (2019). Doing well by doing good: Can voluntary CSR reporting enhance financial performance? Journal of Indian Business Research, 11(2), 100–119.

Orlitzky, M. (2001). Does firm size comfound the relationship between corporate social performance and firm financial performance? Journal of Business Ethics, 33(2), 167–180.

Ortas, E., Álvarez, I., Jaussaud, J., & Garayar, A. (2015). The impact of institutional and social context on corporate environmental, social and governance performance of companies committed to voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 673–684.

Palmer, K., Oates, W. E., & Portney, P. R. (1995). Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 119–132.

Porter, M. E., & Van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 97–118.

Qi, Y., Chai, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2021). Threshold effect of government subsidy, corporate social responsibility and brand value using the data of China’s top 500 most valuable brands. PLoS ONE, 16(5), e0251927.

Reimann, F., Ehrgott, M., Kaufmann, L., & Carter, C. R. (2012). Local stakeholders and local legitimacy: MNEs’ social strategies in emerging economies. Journal of International Management, 18(1), 1–17.

Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. (2016). Social responsibility and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(2), 137–151.

Roodman, D. (2009). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136.

Ruan, L., & Liu, H. (2021). Environmental, social, governance activities and firm performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 13(2), 767.

Sarker, T. K. (2013). Voluntary codes of conduct and their implementation in the Australian mining and petroleum industries: Is there a business case for CSR? Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 2(2), 205–224.

Sharma, E., & Sathish, M. (2022). “CSR leads to economic growth or not”: An evidence-based study to link corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities of the Indian banking sector with economic growth of India. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 67–103.

Škare, M., & Golja, T. (2014). The impact of government CSR supporting policies on economic growth. Journal of Policy Modeling, 36(3), 562–577.

Smith, J. B., & Sims, W. A. (1985). The impact of pollution charges on productivity growth in Canadian brewing. The Rand Journal of Economics, 16(3), 410–423.

Su, W., Peng, M. W., Tan, W., & Cheung, Y. L. (2016). The signaling effect of corporate social responsibility in emerging economies. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 479–491.

Sun, J., Yoo, S., Park, J., & Hayati, B. (2019). Indulgence versus restraint: The moderating role of cultural differences on the relationship between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance. Journal of Global Marketing, 32(2), 83–92.

Tarmuji, I., Maelah, R., & Tarmuji, N. H. (2016). The impact of environmental, social and governance practices (ESG) on economic performance: Evidence from ESG score. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 7(3), 67–74.

Taylor, J., Vithayathil, J., & Yim, D. (2018). Are corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives such as sustainable development and environmental policies value enhancing or window dressing? Corporate Social Responsibility, 25(5), 971–980.

Trumpp, C., & Guenther, T. (2017). Too little or too much? Exploring U-shaped relationships between corporate environmental performance and corporate financial performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(1), 49–68.

Vallentin, S. (2015). Governmentalities of CSR: Danish government policy as a reflection of political difference. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(1), 33–47.

Velte, P. (2017). Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(2), 169–178.

Vishwanathan, P., Van Oosterhout, H., Heugens, P. P., Duran, P., & Van Essen, M. (2020). Strategic CSR: A concept building meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 57(2), 314–350.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 303–319.

Wang, H., & Choi, J. (2013). A new look at the corporate social-financial performance relationship: The moderating roles of temporal and interdomain consistency in corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 39(2), 416–441.

Wang, H., Choi, J., & Li, J. (2008). Too little or too much? Untangling the relationship between corporate philanthropy and firm financial performance. Organization Science, 19(1), 143–159.

Wang, H., Tong, L., Takeuchi, R., & George, G. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: An overview and new research directions. Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 534–544.

Wright, P., & Ferris, S. P. (1997). Agency conflict and corporate strategy: The effect of divestment on corporate value. Strategic Management Journal, 18(1), 77–83.

Wu, C., Xiong, X., & Gao, Y. (2022). Does ESG certification improve price efficiency in the Chinese stock market? Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 29(1), 97–122.

Yim, S., Bae, Y. H., Lim, H., & Kwon, J. (2019). The role of marketing capability in linking CSR to corporate financial performance. European Journal of Marketing, 53(7), 1333–1354.

Zhang, X., & Guo, R. (2018). The inverted U-shaped impact of corporate social responsibility on corporate performance. Journal Finance and Economics, 6(2), 67–74.

Zhang, H., Zheng, Y., Zhou, D., & Zhu, P. (2015). Which subsidy mode improves the financial performance of renewable energy firms? A panel data analysis of wind and solar energy companies between 2009 and 2014. Sustainability, 7(12), 16548–16560.

Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Xue, Y., & Yang, J. (2018). Impact of environmental regulations on green technological innovative behavior: An empirical study in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 188, 763–773.

Zhang, Q., Cao, M., Zhang, F., Liu, J., & Li, X. (2020). Effects of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and organizational attractiveness: A signaling perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review, 29(1), 20–34.

Zhao, C., Guo, Y., Yuan, J., Wu, M., Li, D., Zhou, Y., & Kang, J. (2018). ESG and corporate financial performance: Empirical evidence from China’s listed power generation companies. Sustainability, 10(8), 2607.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, E.T., Li, X. Too much of a good thing? Exploring the curvilinear relationship between environmental, social, and governance and corporate financial performance. Asian J Bus Ethics 11, 399–421 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00157-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00157-y