Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between perceived barriers to self-care, illness perceptions, metabolic control and quality of life. Sixty patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, aged 30–60 years, were recruited from the endocrinology department of a general hospital in Bangalore. They were assessed on the Barriers to Self-Care scale, Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (Revised), Summary of Diabetes-Specific Self-Care Activities. The outcomes were assessed by the brief Diabetes Quality of Life scale and the current glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level. Results were analysed using descriptive statistics, correlation coefficients and regression analysis. Perceived barriers to self-care were significantly associated with identity, consequence, timeline cyclical, and emotional representation, personal control, treatment control and illness coherence dimensions of illness perceptions. Self-care was associated with personal and treatment control and illness coherence dimensions of illness perceptions. Self-care was positively associated with metabolic control. Barriers to self-care were associated with self-care and were an important predictor of self-care and quality of life. The findings of this study emphasize the importance of social cognitive variables such as illness perceptions, self-efficacy beliefs and perceived barriers in impacting self-care and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Diabetes mellitus is a challenging disease to manage, and self-care is crucial for optimal control [1, 2]. Attaining adequate metabolic control is difficult, and patients continue to experience health problems [3].

India has the largest number of patients with diabetes [4]. Asian Indians are more prone to developing diabetes and at younger ages due to a combination of Asian Indian phenotype and low levels of physical activity [4–7]. Management of diabetes mellitus is marked by challenging behavioural complexities, often difficult to sustain over time [8].

Non-adherence is related to patient, treatment, illness or doctor-patient relationship factors [9]. Barriers to self-care are an important factor affecting self-care and a central component of the Health Belief Model. It helps understand adherence to health behaviour on the basis of social cognitive variables such as illness beliefs [10].

A perceived barrier is the person’s estimation of the level of challenge of various social, economic and personal obstacles to a specified behavioural target [11]. It is associated with significantly worse diet and exercise behaviours [12]. Health beliefs are a major source of barriers to self-care in diabetes mellitus and include denial, failure to recognize risks and consequences of an asymptomatic condition, lack of perceived costs and benefits [13, 14]. Inadequate knowledge, helplessness and frustration due to poor glycemic control and continued disease progression despite one’s efforts are important along with system barriers [15]. Perceived barriers are affected by cognitions pertaining to health and illness.

Illness representations determine a person’s appraisal of an illness situation and health behaviour [16]. Negative emotional representations, such as beliefs that diabetes is permanent, are difficult to control and have serious consequences and are linked to poor health outcomes. Patients who believe their condition is more controllable have better self-care with regard to diet, exercise and glucose testing [17].

In India, patients with diabetes face additional challenges including poor awareness, poor accessibility to health-care facilities, medical costs cultural beliefs and practices [18]. Studies on minorities report the experience of culturally intertwined barriers in achieving metabolic control [19]. Research on barriers to lifestyle change in south Asian communities has been conducted on patients living in western societies and cannot be generalized to those living in India [20]. Lifestyle modification programmes must be culturally sensitive. Literature identifies various barriers to physical activity in migrant South Asian women such as the barriers in the use of mixed-gender groups for physical activity; clothing, unsuitable for exercise; not viewing exercise as culturally appropriate [21, 22]. Studies from India show that men report significantly greater exercise-related barriers such as problems with location, negative attitude, lack of time and equipment, while in women, barriers were related to feelings, time and cost [23].

The outcome of a treatment regimen is measured in terms of its ability to achieve desired health outcomes. Optimal metabolic control and quality of life (QoL) are important health outcomes in diabetes care. Diabetes mellitus places serious constraints on patient activities, impacting QoL. Long-term micro- and macro-vascular complications of diabetes negatively impact health and QoL [24].

Barrier identification is critical in minimizing adverse effects on adherence to self-management programmes [25]. Practitioners are encouraged to facilitate patients in the identification of strategies to reduce barriers, facilitate integration of self-care into daily activities and promote self-care behaviours. Self-efficacy beliefs and negative mood affect self-care behaviours. They must be addressed in clinical practice with reference to adherence. Although India has a large population of patients with type 2 diabetes, there is a dearth of studies examining barriers to self-care. The present study explored perceived barriers to self-care, illness perceptions in relation to self-care, metabolic control and QoL.

Research design and methods

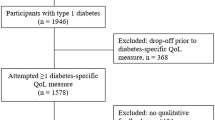

Design and participants

The study was cross-sectional. The sample consisted of 60 patients aged 30–60 years (mean = 50.72, SD = 7.00) with type 2 diabetes mellitus, attending outpatient services of the department of endocrinology of a medical college in Bangalore, India.

Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and illness duration of at least 1 year. The diagnosis was reviewed by a senior endocrinologist (GB). Patients with myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular illness, major psychiatric disorders and current substance dependence were excluded. Psychiatric conditions were ruled out based on a clinical interview by the first author (AMA). Consecutive patients presenting to the endocrinology outpatient who met the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria were screened by the consultant physician (GB), and informed consent was obtained from the patients, and assessments were carried out. Out of the 65 patients contacted, three refused consent and two did not complete the assessments. Thus, the final sample consisted of 60 participants. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institute Ethics Committee. The data collection was carried out between August 2010 and December 2010. Assessments were carried out in English and the local language Kannada. All tools were translated and back translated and reviewed by an expert from the field of clinical psychology.

Measures

Barriers to Self-Care (BSC) scale [26] is a 31-item instrument that assesses perceived barriers to self-care. Patients rated frequency of barriers to self-care on five subscales: barriers to glucose testing, diet, exercise, medication-taking and general barriers. Intercorrelations among the subscale scores are reported to range from r = 0.39 to 0.72. This scale was administered as a semi-structured interview. Participants were also asked a question “What other barriers do you experience in taking care of your diabetes?” in order to obtain relevant data that was not captured by the BSC scale. The findings on this question were collated and are presented as a separate table (Table 5).

The Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) [27] measures perceptions across domains of identity, cause, timeline cyclical, consequences and cure-control. The subscales have good internal reliability and has an adequate test-retest reliability for 3 weeks and 6 months.

The Summary of Diabetes-Specific Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) is a 11-item self-report measure that assesses adherence to diabetes self-care tasks performed over a period of 1 week [28].

Diabetes-specific quality of life was assessed using the brief Diabetes Quality of Life questionnaire [29]. Patients ranked responses on a 5-point Likert scale. It provides a total health-related QoL score that predicts self-reported diabetes care behaviours and satisfaction with diabetes control.

The data on glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was obtained from the most recent medical records of the patient, and no blood samples were drawn for this purpose.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data was analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version15.0). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were conducted to examine relationships among barriers to self-care, illness perceptions self-care, QoL and metabolic control. Predictors of self-care, QoL and metabolic control were determined using stepwise linear regression. Responses to the open-ended question were collated and tabulated based on the type of barriers mentioned.

Results

More than half the sample was women (58.3 %), little less than half the sample (40 %) consisted of homemakers. Fifty-two percent had diabetes between 3 and 10 years (Table 1). A majority (62 %) were on oral medication, 33 % were on a combination of oral medication and insulin therapy. Family history of diabetes mellitus was present in 65, and 36.7 % had comorbid hypertension.

The most significant barriers perceived were general barriers such as having visitors, being too busy and being unwell (3.19 SD = 1.07), followed by diet (2.80 SD = 1.21) and exercise (2.54 SD = 0.98). The total barriers scale score was 2.37 (SD = 0.70). In addition, participants’ response to the open-ended question about barriers to self-care suggested that inflexible diet plans, faulty beliefs related to diet, prioritization of other roles, low mood, and inaccurate beliefs associated with insulin and lack of easy access to laboratory facilities were barriers in self-care.

Patients perceived few changes in their symptoms, and few of these were attributed to their illness (identity = 3.72 and cyclicality = 8.60 on IPQ-R). They perceived consequences of illness in terms of financial costs (mean = 18.5).

Adherence to general care was an average of 5.29 and 5.42 days per week of specific diet recommendation. Variability in following exercise recommendations was greatest (average of 4.08 days per week). The mean days per week blood sugar was tested was 1.33. Foot care was the least frequently practised self-care activity (0.55 days/week).

Participants reported experiencing a moderate QoL (mean = 33.40, SD = 10.36). A substantial portion of the sample had poor metabolic control with a mean HbA1c count of 8.20 (SD = 1.84, 66 mmol/mol).

Associations between variables

Illness representations and barriers to self care (Table 2), identity (r = 0.442; p < 0.01), consequence (r = 0.628; p < 0.01), timeline cyclical-dimension on IPQ-R (r = 0.350; p < 0.06) and emotional representation dimension (r = 0.707; p < 0.01) were positively correlated with total barriers score on the Barriers of Self-Care scale. Individuals who experienced a greater number of symptoms attributed to their illness and believed that the illness is long standing with negative consequences, experienced barriers more frequently. Personal control (r = −0.416; p < 0.01), treatment control (r = −0.416; p < 0.01), and illness coherence (r = −0.455; p < 0.01) were negatively correlated with the total barriers scale, indicating that the belief that one was in control of their illness was associated with self-efficacy beliefs and fewer perceived barriers to self-care.

Perceived barriers to diet were associated with poor self-care with regard to adherence to diet-general (r = −0.441; p < 0.01) and specific (r = −0.378; p < 0.01), and perceived barriers to exercise was associated with poor adherence to exercise regimens (r = −0.709; p < 0.01) (Table 3).

General diet (r = −0.293; p < 0.05), specific diet (r = −0.316; p < 0.05) and exercise (r = −0.299; p < 0.05) were associated with lower HbA1c, indicating better metabolic control (Table 4).

Better self-care was associated with better QoL (Table 4). Self-care with regard to general diet (r = −0.658; p < 0.01), specific diet (r = −0.661; p < 0.01) and exercise (r = −0.731; p < 0.01) were associated with lower scores on the diabetes QoL, indicating that adherence to treatment regimens are associated with better perceived QoL (Table 5).

Barriers to self-care was a significant predictor of self care (F = 49.93; p < 0.05, R 2 = 0.453). Barriers to self-care, illness-perception identity, self-care exercise, self-care-specific diet and illness perception-timeline cyclical were significant predictors of diabetes-specific QoL, accounting for 83.5 % (R 2 = 0.453) of the variance in QoL.

Discussion

We explored perceived barriers to self-care, illness perceptions and self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus from the Indian subcontinent. Our sample is representative of patients seeking treatment at general hospitals in India [11]. Over half the sample had duration of illness between 3 and 10 years and 15 % had diabetes for longer than 10 years.

The concept of perceived barriers is central to health behaviour theories. Perceived barriers are crucial in shaping one’s self-efficacy expectations and problem-solving attempts, which in turn, lead to the performance of self-care behaviours [12].

General barriers such as being busy, having visitors, and being unwell were the most frequently experienced barriers, followed by barriers in following healthy dietary patterns. Poor knowledge about diabetes-specific diet was also a barrier to self-care. Participants also cited that inflexible diet charts and not having assistance with cooking healthy food were barriers. Some also held faulty beliefs such as the consumption of food such as garlic or bitter gourd would improve sugar levels thereby allowing them to indulge in unhealthy food. Studies report that the most frequently reported barriers patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus experience include high cost of medication, lack of time, competing demands, social pressures, poor self-efficacy and negative cognitions about the illness [24]. These findings emphasize the need for psychological and educational interventions such as practical, skill-based information that are easily comprehended and empower patients in treatment.

Exercise-related barriers were common and lack of time and motivation, being at an inconvenient location were reasons cited. Other barriers to exercise included low mood states or stress, the perception of exercise as monotonous, and frustration associated with not experiencing immediate weight loss or improvement in sugar levels. Homemakers cited responsibility towards their family as being of greater priority than self-care. This finding is consistent with a study carried out in southern India that reports gender differences in barriers to self-care [24].

Barriers to glucose testing were least frequently cited and this is probably because the overall incidence of participants testing glucose at home was low. Over half the participants tested blood at medical centres, only prior to visits to the physician. Inability to afford the costs of home blood glucose testing was also reported, as a majority belonged to the middle and lower middle economic background. Participants also reported not testing blood glucose levels in order to avoid negative mood states associated with high sugar levels. In addition, we found that incorrect beliefs such as “insulin is synonymous with death” and “once a person starts taking insulin, it would have to be taken lifelong”, interfered with compliance to insulin.

Individuals’ illness representations influence the coping strategies they use to deal with the illness and minimize the threat posed by the illness. Personal beliefs about health problems have been reliably associated with emotional and behavioural responses to health problems and outcomes [30].

The most commonly identified symptoms were fatigue and weakness, likely due to poor metabolic control. Cyclical changes in symptoms were infrequently experienced, and participants experienced diabetes as a stable and long-lasting illness without the major fluctuations in symptoms. Type 2 diabetes is often asymptomatic in many individuals [31].

There was a sense of clarity and coherence with respect to the illness and meaning-making about the condition, possibly because over 66 % had the illness for a minimum duration of 3 years and had been on regular follow-up. Patients who are on regular follow-up experience significantly lower levels of anxiety and greater levels of energy and QoL than those with less frequent follow-up [32].

Financial costs of the illness were perceived as an important consequence of the illness. Cost was a barrier to medication use. Dose omissions were frequent among participants from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, especially when they were unable to present for follow-ups.

Men reported that their spouses had to make additional efforts to follow the recommended diet, while women required the assistance of male family members to attend follow-ups. This highlights the differential impact that a chronic illness like diabetes mellitus has on gender.

According to the self-regulatory model [17] people develop parallel cognitive and emotional representations in response to illness, which determine problem-based and emotion-focused coping procedures, respectively [17]. In the present sample, scores on emotional representation dimension was moderate. More than 66 % had been diagnosed for at least 3 years, possibly resulting in greater acceptance [32].

The belief in chronicity of the condition was high as seen on the timeline dimension. Chronicity is an important cognition and is associated with wavering motivation and poor self-care. While participants had adequate knowledge about diabetes, research indicates that knowledge regarding diabetes is still grossly inadequate in India, indicating the need for diabetes education programmes both in urban and rural India [33]. Studies have demonstrated that educational interventions can be successful in reducing obesity parameters and improving dietary patterns of individuals with prediabetes and diabetes [33]. The present sample reported positive beliefs about controllability of diabetes, on personal and treatment control dimensions. Participants reported being confident that their actions could influence their well-being and determine the course of the illness. Increased perceptions of control and understanding of diabetes are associated with better adherence to diet and lesser interference with social and personal functioning. Perceived control was associated with a more positive attitude towards life in general [34].

Self-care on the domains of diet was fair. Over a 1-week period, participants exercised for about 4.08 (SD = 2.79) days, 20–30 min per day. There was considerable variability with respect to recommendations for exercise being followed. While some reported high motivation and regularity with engaging in physical exercise, others cited lack of time, fatigue, pain in the lower limbs, prioritization of other tasks, as barriers.

There was considerable variability on the measure of QoL. A majority indicated experiencing a moderately satisfying QoL. Our findings were contrary to studies that report QoL among people with diabetes to be worse than that of a general population [35].

Patients experienced greater barriers to self-care across various dimensions more frequently. Barriers such as being at a restaurant during meal times, poor knowledge about diabetes-specific diet and the lack of clarity about portion size were associated with poorer adherence to diet. This is largely consistent with the findings of an Indian study that found that busy lifestyles made it more difficult to follow regimented inflexible printed diet charts [36] and suggests that recommendations should be more patient friendly. The study also highlights the importance of family support in adherence to dietary regimens.

Patients’ perceptions of their diabetes have been found to influence emotional well-being and self-care. The findings on IPQ-R suggest that identity was negatively associated with self-care in terms of diet and exercise. Individuals who experienced multiple symptoms and attributed them to diabetes engaged in less frequent self-care behaviours. It is possible that distressing symptoms experienced by participants can themselves be barriers to self-care and contribute to poor self-efficacy with respect to self-care behaviours.

The consequence dimension (IPQ-R) was negatively correlated with self-care. The perceived consequences dimension of the personal model is to both perceived severity of diabetes and perceived susceptibility to complications of diabetes and to perceived impact of diabetes. Perceived consequences may be important in determining an individual’s emotional response to diabetes, which in turn impacts self-care.

The belief regarding control plays an important role in determining illness outcome and contributes to a sense of responsibility about engaging in self-care activities. Research also indicates that patients who believe their condition is more controllable have better self-care in the areas of diet, exercise and glucose testing [37]. In the present study, negative illness perceptions and unpleasant emotional representations of the illness were associated with greater perceived barriers to self-care. These illness perceptions were also associated with poorer self-care with regard to diet and exercise.

Self-care was positively related to QoL and metabolic control. Contrary to the belief that treatment regimens that require adherence leads to decreased QoL, we found that better self-care can empower patients, helping them have QoL. Our finding is consistent with studies that have demonstrated that better glycaemic control is associated with better mood and well-being, while lower adherers tend to perceive more negative effects of the illness, contributing to poorer perceived QoL [38].

Barriers to self-care emerged as the single largest predictor of self-care with regard to general and specific diet. Forty-five percent of the variance in self-care general diet was explained by barriers to self-care such as diet- and exercise-related barriers, barriers to medication and glucose testing and general barriers. The more frequent the experience of barriers to self-care, the poorer was self-care, in line with previous research. This finding highlights the need for diabetes care providers to address environmental and psychosocial barriers to optimal self-care during routine consultations in order to sustain healthy behaviours.

The present study had certain limitations that restrict generalizability of findings. These include a small sample size, a restrictive age range and the use of self-report measure of self-care that reduces the reliability of information. A larger, more proportionately stratified sample would enable greater understanding of these variables in younger patients. However, there is an inherent difficulty in the measurement of self-care. Unequal representation of treatment type did not allow for comparison across treatments.

Conclusions

Barriers to self-care and illness beliefs impact self-care and health outcomes. They must be included when planning effective, culturally relevant psychological and educational interventions for chronic medical illnesses.

References

Sigurdardottir AK. Self-care in diabetes: model of factors affecting self-care. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(3):301–14.

Polly RK. Diabetes health beliefs, self-care behaviors and glycemic control among older adults with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ. 1992;18:321–7.

Delamater AM. Improving patient adherence. Clin Diabetes. 2006;24:71–7.

Mohan V, Sandeep S, Deepa R, Shah B, Varghese C. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:217–30.

Hayes L, White M, Unwin N, Bhopal R, Fischbacher C, Harland J, et al. Patterns of physical activity and relationship with risk markers for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and European adults in a UK population. J Public Health Med. 2002;24(3):170–8.

Fischbacher CM, Bhopal R, Steiner M, Morris AD, Chalmers J. Is there equity of service delivery and intermediate outcomes in South Asians with type 2 diabetes? Analysis of DARTS database and summary of UK publications. J Public Health. 2009;31(2):239–49.

Mather HM, Chaturvedi N, Fuller JH. Mortality and morbidity from diabetes in South Asians and Europeans: 11-year follow-up of the Southall Diabetes Survey, London, UK. Diabet Med. 1998;15(1):53–9.

Gary TL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioural interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:488–501.

Levensky ER, O’Donohue WPO. Patient adherence and nonadherence to treatment. In: Levensky ER, O’Donohue WPO, editors. Promoting treatment adherence: a practical handbook for healthcare providers. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2006. p. 6.

Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1.

Patel M, Patel I, Patel YM, Rathi SK. A hospital-based observational study of type 2 diabetic subjects from Gujarat, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(3):265–72.

Glasgow RE. Perceived barriers to self management and preventive behaviours. National Cancer Institute. 2003. Available from: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/constructs/barriers/barriers.pdf. Accessed 05 July 2011.

Aljasem L, Peyrot M, Wissow L, Rubin R. The impact of barriers and self-efficacy on self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27:393–404.

Gazmararian J, Ziemer D, Barnes C. Perception of barriers to self-care management among diabetic patients. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(5):778–88.

Tu KS, Barchard K. An assessment of self-care barriers in older adults. J Community Health Nurs. 1993;10:113–8.

Nagelkerk J, Reick K, Meengs L. Perceived barriers and effective strategies to diabetes self-management. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(2):151–8.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to medical psychology. 2nd ed. New York: Pergamon; 1980.

Paddison C, Alpass F, Stephens C. Psychological factors account for variation in metabolic control and perceived quality of life among people with type 2 diabetes in New Zealand. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:180–6.

Potluri R, Purmah Y, Dowlut M, Sewpaul N, Lavu D. Microvascular diabetic complications are more prevalent in India compared to Mauritius and the UK due to poorer diabetic control. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;86(2):39–40.

Rosal MC, Ockene IS, Restrepo A, White MJ, Borg A, Olendzki B, et al. Literary-sensitive, culturally tailored diabetes self management intervention for low income Latinos. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):833–44.

Simmons D, Williams R. Dietary practices among Europeans and different South Asian groups in Coventry. Br J Nutr. 1997;78(1):5–14.

Vishram S, Crosland A, Unsworth J, Long S. Engaging women from South Asian communities in cardiac rehabilitation. Br J Community Nurs. 2007;12(1):13–8.

Stone M, Pound E, Pancholi A, Farooqi A, Khunti K. Empowering patients with diabetes: a qualitative primary care study focusing on South Asians in Leicester, UK. Fam Pract. 2005;22:647–52.

Sridhar GR, Madhu K, Veena S, Madhavi R, Sangeetha BS, Rani A. Living with diabetes: Indian experience. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2007;1:181–7.

U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group: Diabetes Study Group: Quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients is affected by complications but not by intensive policies to improve blood glucose or blood pressure control (UKPDS 37). Diabetes Care. 1999;22(7):1125–36

Nam S, Chesla C, Stotts NA, Kroon L, Janson SL. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93:1–9.

Glasgow RE. Social-environmental factors in diabetes: barriers to diabetes self care. In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of psychology and diabetes. Newark: Harwood Academic; 1994. p. 335–50.

Moss-Morris AD, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The revised illness perceptions questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health. 2002;17:1–16.

Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE. Assessing diabetes self-management: the summary of diabetes self-care activities questionnaire. In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of psychology and diabetes. Newark: Harwood Academic; 1994. p. 351–78.

Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA, Patrick-Miller L, et al. Illness representations: theoretical foundations. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman J, editors. Perceptions of health and illness. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic; 1997. p. 19–46.

Engelgau MM, Narayan KMV, Herman WH. Screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults. Diabetes Care. 2000;18:1563–80.

Deepa M, Deepa R, Shanthirani CS, Manjula D, Unwin NC, Kapur A, et al. Awareness and knowledge of diabetes in Chennai—the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (Cures—9). J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:283–7.

Balagopal P, Kamalamma N, Patel TG, Mishra R. A community-based diabetes prevention and management education program in a rural village in India. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1097–104.

Connell CM, Davis WK, Gallant MP, Sharpe PA. Impact of social support, social cognitive variables, and perceived threat on depression among adults with diabetes. Health Psychol. 1994;13:263–73.

Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–18.

Kapur K, Kapur A, Ramachandran S, Mohan V, Aravind SV, Badgandi M, et al. Barriers to changing dietary behavior. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:27–32.

Glasgow RE, Hampson SE, Strycker LA, Ruggiero L. Personal-model beliefs and social environmental barriers related to diabetes self management. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:556–61.

Al-Shehri AH, Taha AZ, Bahnassy AA, Salah M. Health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:352–60.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. D. K. Subbakrishna for his inputs on the study.

Funding

None

Conflict of interest

None

Author contributions

The paper is based on the academic research carried out by A.M.A. A.M.A. carried out the assessments, wrote the manuscript; P.M.S. supervised the planning of the study and assessments, reviewed and edited the manuscript; M.P. contributed to the statistical analysis of the data and reviewed the manuscript; G.B. screened patients for the study, reviewed the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abraham, A.M., Sudhir, P.M., Philip, M. et al. Illness perceptions and perceived barriers to self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: an exploratory study from India. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 35 (Suppl 2), 137–144 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-014-0266-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-014-0266-z