Abstract

Homophobic name-calling is one of the most common forms of gender-based violence that occurs among young people at school. Yet students are reluctant to seek teacher help when homophobic bullying occurs. We investigated what enables bystanders to seek help from teachers when they witness the homophobic harassment of a peer who may be unwilling to seek help for themselves. Respondents were a sample of 2119 secondary students from 11 Australian schools. Data analysed using generalised mixed linear modelling demonstrated that student connectedness to teachers at the individual and school level were the strongest predictors of the likelihood of reporting the homophobic harassment of a peer. Findings suggest that above and beyond the effects of student relationships with teachers, a culture of teacher care at the school level is crucial in enabling students who witness homophobic bullying to seek teacher help.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Homophobic harassment is a persistent form of gender-based violence, commonly targeted towards people on the basis of their perceived deviation from heterosexual gender norms (Meyer, 2008; Poteat & Russell, 2013). Despite increased imperatives to prevent bias-based harassment in schools, adolescents continue to report that homophobic behaviour goes largely unaddressed (J. G. Kosciw et al., 2012). Homophobic victimisation tends to intensify in adolescence and is a widely reported experience among sexual and gender minority students in secondary schools (Mitchell et al., 2014). One research study conducted in Australia found that at least 80% of same-sex attracted and gender diverse students experienced verbal or physical harassment at school based on their sexual orientation or gender identity (Hillier, 2010). A survey of secondary school students in the United States also found that 33.7% reported calling peers homophobic names, and 31.3% reported being the victim of homophobic name-calling (Rinehart & Espelage, 2016), highlighting the pervasive and normalised nature of homophobic harassment among both heterosexual and non-heterosexual young people.

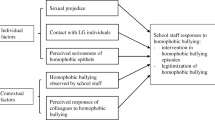

In this paper, we focus on bystander responses to homophobic name-calling, a particular yet common form of harassment that involves the use of pejorative language related to a person’s perceived sexual orientation (e.g. calling others “gay” in a denigrating way). Our interest follows the assumption that bullying is a social phenomenon, and thus it is important to understand school factors that influence the intentions of peers to intervene on the part of victimised classmates. In particular, we sought to find if, beyond the quality of student relationships with teachers, that student perceptions of being part of a school environment of care contributes to their intentions to seek help from a teacher on behalf of a friend.

Homophobia and peer policing of gender expression

Peer group culture plays an important role in the formation, perpetuation and normalisation of homophobic bullying (Birkett & Espelage, 2015). Homophobic name-calling is a form of verbal harassment used to police expressions of masculinity amongst both LGBTIQ + and heterosexual young people. Given the nature and prevalence of homophobic name-calling, researchers have argued that the concept of homophobia is insufficient to describe adolescents’ use of homophobic epithets (Thompson, 2019). This practice does not require queer-identified subjects to operate (Allen, 2018), and has been described as the most common form of aggression used to enforce narrow expressions of masculinity, regardless of sexual orientation (McCormack, 2011). Homophobic epithets are used as a means of asserting and maintaining dominant gender norms within groups (Fulcher, 2017; Swearer et al., 2008). They function to ‘warn’ others not to subvert the heterosexual norms perceived to be integral to the status and membership of a group (Merrin et al., 2018). They are also used to target non-heteronormative or gender non-conforming young people in an effort to punish or shame those who have already deviated from these norms (Ringrose & Renold, 2010).

Impacts of homophobic bullying on wellbeing

Efforts to prevent homophobic harassment are important, as LGBTIQ + youth experience more serious harm than their peers from homophobic language use at school (Poteat et al., 2011). Studies demonstrate increased rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicidality amongst LGBTIQ + youth (Collier et al., 2013; Poteat & Espelage, 2007), as well as negative impacts upon their school attendance and achievement (Rivers, 2000).

These practices also diminish school connectedness for all members of school communities, including bystanders and allies (Rasmussen et al., 2017). Those who witness the homophobic victimisation of others may also experience negative mental health outcomes, including heightened anxieties around their own vulnerabilities (D'Augelli et al., 2002; Rivers et al., 2009). Perpetration of homophobic harassment in early adolescence, moreover, has been associated with escalation into sexual violence perpetration in later adolescence (Espelage et al., 2018), pointing to the importance of interventions which work to avert such behaviour. Given this, gender-based violence prevention efforts should explicitly include a focus on the prevention of homophobic name-calling, and address the traditional heterosexual gender norms that contribute to sexual violence. This is consistent with evidence that whole school approaches to reducing homophobic discrimination have positive impacts on overall student wellbeing (Poteat et al., 2013; Russell et al., 2016).

Seeking help from teachers for homophobic harassment

Teachers often underestimate the extent, nature, and locations of homophobic victimisation at school (Yablon, 2010), and this lack of awareness can inhibit their use of effective prevention and intervention strategies. Consistent with broader patterns of reluctance to seek help for bullying, students tend not to seek help from teachers around perpetration of homophobic name-calling (J. Kosciw et al., 2014). Low levels of reporting about bias-based harassment can lead to underestimation by teachers of the prevalence, severity and impact of this form of gender-based violence (Waasdorp et al., 2011).

Help-seeking intentions and actions are influenced both by peer norms and relationships and by student/teacher relationships. Studies demonstrate that students are more likely to seek help from teachers with whom they have positive relationships (Eliot et al., 2010). Indeed strong teacher/student relationships positively impact many aspects of students’ lives, including enhanced mental health, social competence, relationships with peers and adults, and academic success (Holfve-Sabel, 2014).

The inclusion of education initiatives which explicitly teach about gender, sexuality, and bias-based harassment have also been shown to improve the likelihood of student help-seeking, with students more likely to report homophobic bullying to those teachers who have provided these kinds of lessons for them (O’Donoghue & Guerin, 2017). In schools where teachers are seen to intervene upon witnessing homophobic bullying, student willingness to report or to seek help is higher and prevalence rates are lower (Berger et al., 2019). Seeing teachers intervene normalises and empowers students to intervene themselves (Wernick et al., 2013). A study conducted in Chilean high schools found that students were more likely to trust teachers who consistently intervened against homophobic comments, which in turn was associated with higher student willingness to report homophobic victimisation (Berger et al., 2019). One explanation for this association might be that such trust reduces barriers associated with help-seeking, such as fear of exacerbation, and lack of confidence in adults to respond effectively (Gulliver et al., 2010). In turn, seeing peers intervene against homophobic harassment positively influences student willingness to report their own or others’ victimisation to an adult (Berger et al., 2019).

Conversely, students are less willing to report or to seek help for homophobic victimisation in schools where students find teacher intervention efforts to be ineffective, where they believe that little action will be taken, or that asking for help will exacerbate the situation (Goldweber et al., 2013). Such beliefs are common, with LGBTIQ + students reporting that reporting homophobic victimisation to a teacher was most frequently met with inaction or an ineffective response (J. Kosciw et al., 2014).

Teachers and school environments

A range of educational outcomes have been associated with student/teacher relationships. Students who find their teachers to be caring and supportive show higher academic progress (Gregory & Weinstein, 2004), higher school and academic engagement (Maehr, 1991) and achieve higher grades (Goodenow, 1993). Positive relationships between students and teachers improve student well-being and contribute to a conducive climate for learning (Hamre & Pianta, 2001).

According to Gregory et al. (2010), secondary schools have lower rates of student victimisation and bullying among students when they provide fair enforcement of clear rules along with adults who demonstrate a caring and supportive relational style.

In this article we add to this interest in exploring student perceptions of the quality of student–teacher relationships at the school level by investigating their intentions to seek help from a teacher on behalf of a friend who experiences homophobic name-calling. We sought to investigate the extent to which their overall perception that the school has caring and supportive teachers influences their help-seeking intentions, and the extent to which perceptions of school climate as well as teacher-student relations might influence help-seeking. We sought to understand if student likelihood to seek help for a friend is associated with an overall perception that, beyond the individual student experiences with teachers at school, the staff culture of the school would be conducive to a positive response. We investigated whether students who believe that teachers in the school are caring and supportive are more likely to intend to seek help for a friend victimised by homophobic name-calling regardless of the opinion of his/her classmates about these issues. Are overall perceptions of teacher care and support at the school level relevant beyond student personal experiences with teachers? Ultimately, do supportive school environments contribute to student intentions to seek help from a teacher beyond their individual perceptions of student–teacher relationships?

The study

There is a dearth of quantitative research which investigates the factors that influence the likelihood of bystanders to report instances of homophobic harassment to teachers, as much of the research thus far has examined the help-seeking intentions and action of the direct targets of harassment. In response, this paper explores the relationship between teacher/student relationships and willingness of bystanders to seek help from a teacher on behalf of a victimised peer.

This paper uses survey data collected from secondary students within a broader study (Cahill et al., 2016, 2019) investigating the implementation of a social and emotional learning program and respectful relationships education program (Cahill & Dadvand, 2020; Dadvand & Cahill, 2020). Within this study students were surveyed about their mental health and social relationships, including their witnessing of gender-based bullying and victimisation. Most questions were on a 5-point Likert style scale, with higher scores indicating higher endorsement of the item. Questions on bullying, coping, and help-seeking provided participants with a list of options, and respondents selected all that applied to them. Ethics approval for the data collection was provided by the ethics committees of the University of Melbourne and the Department of Education Victoria, and a full opt in was required involving active informed consent from students and their parents.

Research methods

The study collected data from 2119 students in Year levels 7 to 10, in 11 schools (10 secondary schools and one P-12 school) in the state of Victoria, Australia during 2017 and 2018. Almost half of the students were female (48.9%), and the remaining were male (46.5%), or identified as other gender (38 students, 1.8%). Data reported in this paper correspond to a selected subsample of 1750 students that had valid data in all the variables included in the study. Due to this restriction in responses across all the variables, students who identified as other gender were not in the selected subsample, which is composed of 871 females and 879 males (see Table 5 in Appendix). This subsample includes students from Year 7 (N = 693), Year 8 (N = 560), Year 9 (N = 357) and Year 10 (N = 140). Using the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) value to denote the relative level of socio-economic disadvantage, two schools were in the low SES category (with 13.2% of respondents), six were in the middle SES level (with 37.5% of respondents), and three were in the high SES category (with 49.3% of respondents). (For more detail see Table 7 in Appendix).

Demographic data included age, school, and options to identify gender as male, female or other, with optional comment box to self-nominate gender. Students were surveyed to gather information about their physical, social and mental health, as well as their attitudes to school and teachers, their coping strategies, and their experiences in relation to victimisation, witnessing or perpetration of bullying and gender-based violence. Data about student mental health are analysed elsewhere (Kern et al., 2020). It demonstrates that females were approximately 1.5 times as likely as males to report high levels of mental health distress, and the highest rates of distress were reported by students identifying as non-binary gender, with 43% (2017) and 35% (2018) of this latter group indicating probable severe psychological distress as identified via use of the K6 measure.

Variables of interest

In the survey, students were given several alternatives to answer the question “If someone was being mean by calling another person gay, it would be more like me to: (i) laugh, (ii) join in, (iii) ignore it, (iv) tell them to stop, (v) tell a friend, (vi) tell my parents/carers, (vii) tell a teacher, (viii) say mean things to them, (ix) hit them, (x) go away, (xi) do nothing”. Students could mark all the alternatives that applied, and students who marked the alternative “Tell a teacher” among them were coded 1, and 0 if they left it blank. Choosing the option to “tell a teacher” among several other alternatives is important, as it implies that it is included in students’ “toolkit” against homophobic name-calling of peers. We interpreted this single-item measure as the likelihood of students reporting homophobic name-calling to a teacher among several actions they can take. A total of 31.6% of students in the sample chose the option to “tell a teacher”, and it is used as the outcome variable to explore student and school characteristics associated with the likelihood of students reporting to a teacher that the word “gay” had been used in a pejorative way about a peer.

Student/teacher and peer connectedness

Students were asked how much they agreed with three statements related to their connectedness to teachers: “My teachers care about me as a person”, “My teachers treat me fairly” and “My teachers respect my ideas and opinions”. Possible answers ranged on a 5-level Likert scale from “Strongly disagree” (coded as 1) to “Strongly agree” (coded as 5). Principal component analysis was conducted to create an index for teacher connectedness at the student level (for properties of this and other scales at the student level see Tables 2 and 8 in Appendix). Values in this multi-item index range from − 3.4 to 1.7, and scores were standardised to have a mean score of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.0, so that positive numbers represent scores above the mean and negative numbers indicate scores below the mean. Standardising scores has the advantage of centring the variables and facilitating the interpretability of the generalised linear mixed model estimates. Scores close to − 3.4 represent low levels of student connectedness to teachers, and values close to 1.7 represent high levels of connectedness.

Students answered four statements about their peer relationships, which were used to create a multi-item measure denominated “peer connectedness”. These included, “I get along well with my friends”, “I’m able to talk about everything with my friends”, “I spend a lot of time with my friends” and “I can rely on my friends”. Possible answers for the first three statements ranged from “Not at all like me” (coded as 1) to “Totally like me” (coded as 5), and for the last statement, from “Strongly disagree” (coded as 1) to “Strongly agree” (coded as 5). The principal component analysis resulted in a minimum value of − 3.9 and maximum value of 1.6, with a mean score of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.0. Scores close to − 3.9 represent low quality peer relationships and values close to 1.6 represent high quality relationships.

Prevalence of homophobic name-calling

The perceived prevalence of homophobic bullying was assessed using two items to create an index through principal component analysis. The index was based on literature highlighting verbal harassment as the most common form of homophobic bullying, with boys more often perpetrators than girls (Birkett & Espelage, 2015; Collier et al., 2013). Students were asked to indicate how many times they had heard boys calling other boys gay or saying they were like a girl during the last week at school, and how many times they had heard girls calling other boys gay or saying they were like a girl. Response options include four alternatives, from 1 = Zero times to 4 = Many times. The minimum and maximum values in the multi-item index are − 0.9 and 2.9, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.0. Values close to − 0.9 indicate low levels of prevalence of homophobic name-calling as perceived by students, and values close to 2.9 indicate high levels of prevalence.

School-level influences as an indicator of school supportive relationships

An aggregate mean score of student–teacher connectedness and an aggregate mean score of quality of peer relationships at the school level were created to explore whether the average level of teacher connectedness and peer relationships in schools influence the likelihood of students reporting homophobic name-calling to a teacher beyond their individual characteristics. In line with work on school support for positive school climate (Gregory & Cornell, 2009) we conceptualised these variables as proxies for school supportive relationships, as they represent the extent to which schools create environments where students feel that their teachers care about them, respect their ideas, and treat them fairly, and where students can develop meaningful and caring friendships. We also created a school level variable of perceived prevalence of homophobic bullying at school, consisting of the aggregate average score across students in each school.

Control variables

Three control variables (two at the student level and one at the school level) were used to ensure the accuracy of estimations about the likelihood of students reporting homophobic behaviour. At the student level, we used gender and year level. In the sample, 50.2% of the students identify themselves as male, while 49.8% identify themselves as female. The gender variable used in the inferential analysis is coded 1 for female and 0 for male. Year level was used to control for student life and academic stages. In the sample, 39.6% of students were in Year 7, 32.0% in Year 8, 20.4% in Year 9 and 8.0% in Year 10.

School size is included as a single-measure control variable at the school level, with data taken from the My School website in 2017. The sample includes schools ranging in size from 110 to 1634 students.

Analytical strategy

First, we conducted a descriptive analysis of the variables of interest by school to examine the relationship between student connectedness to teachers and the likelihood to report homophobic harassment of a peer. This analysis enabled the examination of differences between schools.

Next, we fitted a set of three binary logistic multilevel regression models to examine the association between student connectedness to teachers and the likelihood to tell a teacher if someone was ‘being mean by calling another person gay’. Because students are nested in schools, we employed generalised linear mixed modelling (GLMM) using the GENLIN MIXED program in SPSS version 26, an extension of GLM techniques to multilevel data structures, as it is a suitable command to estimate effects in nested and unbalanced samples using dichotomous outcome variables (Heck et al., 2013). Specifically, we used random intercept models for binomial outcomes. As it is widely known, multi-level modelling recognises that observations are not independent, but rather related to each other as they are nested in higher units that influence them, such as schools. Generalised linear mixed modelling, therefore, allows for better estimation of the degree of variation in the dependent variable by student and school characteristics (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In the first model we included three student level explanatory variables (perceptions of prevalence of homophobic bullying at school, peer connectedness and student/teacher connectedness) and in the second model we included the two student level control variables (gender and year level). All school level variables were added in the third and last model. This strategy allowed us to investigate whether the likelihood of reporting homophobic name-calling to a teacher was significantly related to student connections to peers, teachers and to perceptions of prevalence of homophobic bullying at school, and whether those associations held once gender and year level were included in the model. It also helped to explore whether aggregate student perceptions of supportive teacher relationships at the school level were associated with higher likelihood of approaching teachers when witnessing homophobic name-calling once we accounted for student level and other school control variables. This last component was essential to test if caring and supportive environments at school make a difference in student willingness to report homophobic name-calling to a teacher beyond student individual perceptions of prevalence of bullying at school and the quality of their relationships with peers and teachers.

Results

Table 1 shows the results of the intra-class correlation (ICC) analysis performed to describe the proportion of variance that lies between schools relative to the total variance in student scores in the outcome variable and the three explanatory indices. Considering that the outcome variable is dichotomous and that the variance of a logistic distribution with a scale factor 1.0 is approximately 3.29 (see for example Heck et al., 2013; Hedeker, 2007; Hox, 2002) the estimated ICC, or the variance found between-schools in students reporting homophobic name-calling to a teacher is 7.8%. This means that while most of the variance in the probability of reporting homophobic name-calling to a teacher lies within schools, there is some variability at the school level that could be accounted for student and school level differences between schools.

To illustrate the differences in the proportion of students that reported that they would tell a teacher in case of homophobic bullying between schools, Table 2 shows the percentage of students who reported it would be like them to either tell a teacher, their parents and/or a friend if someone was being mean by calling another person gay. Students could select more than one option. The information is presented for all students in the sample (bottom row) and by the 11 schools in the sample. The most commonly selected option was to report homophobic name-calling to a teacher, with an average of 31.6% selecting this option. The proportion who would tell their parents or a friend was considerably lower (14.1% and 21.7%, respectively).

Table 2 also shows that the proportion of students who believed they would tell a teacher varied between schools. While only 22.4% of students in School C believed they would tell a teacher, as many as 51.0% in School E reported they would take this action. In 10 of the schools, telling a teacher was the most likely action, whilst in one school (C) it was slightly less likely than telling a friend.

Schools also differed in the perceived prevalence of homophobic bullying at school. Table 1 shows that 4.1% of the total variance in student perceptions of prevalence of homophobic name-calling was found between schools. The most frequent form of homophobic bullying perceived by students was to hear boys calling other boys gay or saying that they were like a girl, with 58% of students in the sample reporting that this had happened more than once during the last week at school. Hearing girls use this form of bullying was less frequent, with slightly more than 1 in 3 students reporting it had happened more than once during the last week. Rates varied between schools, with 20.0% of students in one school perceiving this compared to 73.7% of students in another school. Although less prevalent, a similar difference by school was found for perceived perpetration by girls, with 10.0% of students in one school reporting this had happened more than once during the previous week, compared with 51.0 and 50.0% of students in other two schools.

As reported in Table 3, the different proportions in prevalence of homophobic name-calling between schools are reflected in the aggregated index created at the school level. Recall that the multi-item indices were created with a mean of 0.0 and a standard deviation of 1.0, which means that on average, students in the sample had a mean of 0.0 perception of prevalence of homophobic name-calling at school, and under a normal distribution, around 34.1% of cases were expected to be contained within 1.0 standard deviation from the mean. Table 3 shows variability between schools in the index of average student perception of prevalence of homophobic name-calling, with School J scoring 0.72 standard deviations below the mean, and School E scoring 0.27 standard deviations above the mean, confirming the need of exploring school level associations between prevalence of homophobic name-calling at the school level and student likelihood of reporting it to a teacher.

In general, students had positive perceptions about peer connectedness: 84.2% reported that it was totally or a lot like them to get along with friends, and 73.0% felt similar about relying on friends. However, only just over half of students (53.6%) answered that it was totally or a lot like them to be able to talk about everything with friends. In this item there was considerable variations between schools, ranging from 42.4% of students reporting that it was totally or a lot like them to be able to talk about everything with friends in one school, compared to 70.0% of students in another school. However, the ICC coefficient indicated that only 1.1% of the variance in the index of peer connectedness was found between schools (see Table 1), and results in Table 3 confirmed lower levels of variability in average peer connectedness between schools. Due to these findings, average peer connectedness at the school level is only included as a control variable in the generalised linear mixed modelling below.

In all schools, half or more of the students agreed or strongly agreed that their teachers cared about them as a person, treated them fairly and respected their ideas and opinions. On average, around 2 in 3 students in the sample agreed or strongly agreed with these statements. However, student responses differed by school. Results in Table 1 show that 3.0% of the total variance in the index of student/teacher connectedness was found between schools, and Table 3 confirms this variability in terms of the aggregated mean index score between schools. Consequently, the aggregated mean score of student/teacher connectedness at the school level was included as an explanatory variable in the generalised linear mixed modelling that follows.

In all, the previous findings suggested that some schools were more effective at creating environments of supportive relationships, potentially explaining differences in the comfort students felt sharing concerns about homophobic bullying with teachers. The next section presents the results of the generalised linear mixed modelling analysis.

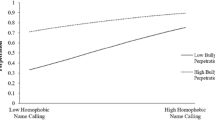

Model 1 in Table 4 revealed that students who perceive high prevalence of homophobic name-calling at school were less likely to say they would tell a teacher when they witnessed homophobic bullying. This is the case in every model in Table 4, with the effect size of prevalence of homophobic name-calling being quite stable across models even in the presence of other variables, suggesting a strong independent effect of perceived prevalence of homophobic name-calling on the likelihood of reporting it to a teacher.

Model 1 also showed that student perceptions of peer connectedness were not significantly associated with the likelihood of telling a teacher if they witnessed someone being a victim of homophobic name-calling at school. However, this likelihood was significantly associated with student opinions about their connectedness to teachers, with a 1.0 unit increase in the student/teacher connectedness scale (1 standard deviation) significantly increasing the odds of reporting homophobic bullying to a teacher by 1.70. In other words, students who felt that their teachers cared about them, treated them fairly and respected their ideas and opinions were more likely than students who did not feel this way to intend to tell a teacher in case of homophobic name-calling, regardless of student perceptions of prevalence of these issues at school.

The inclusion of the student level control variables in Model 2 revealed that girls were significantly more likely than boys to intend to report homophobic bullying to a teacher (1.76 times more likely than boys) and that students in higher year levels were less likely to intend to report homophobic bullying to a teacher. These effects were independent of the effect of all other variables included in Model 2.

Perhaps more interestingly is that Model 2 showed that the association between student perceptions of prevalence of homophobic bullying and student/teacher connectedness at school remained significant even after controlling for student level control variables in the model. Noticeably, the effect sizes of prevalence of homophobic bullying and student/teacher connectedness at the student level did not change considerably by the introduction of student-level control variables, suggesting no moderation effects of gender and year level.

Model 3 incorporates the explanatory and control variables at the school level, and shows that the only significant association with student likelihood of reporting homophobic bullying was average student/teacher connectedness. A 1.0 unit increase in the average student/teacher connectedness scale (1 standard deviation) at the school level increased the odds of telling a teacher by almost 12, holding constant all other variables in the model, including the effect of student level perceptions of student/teacher connectedness. Regardless of student personal relationships with teachers and peers and perceived levels of bullying at school, students were more likely to intend to tell a teacher in case of homophobic name-calling in schools where most students felt that teachers cared about them, treated them fairly and respected their ideas and opinions.

As suggested in the descriptive analysis, average peer connectedness at the school level was not significantly associated with student likelihood of reporting homophobic bullying to a teacher. More surprising was the lack of significant association between average prevalence of homophobic name-calling and student likelihood of reporting homophobic bullying to a teacher. This result suggests that two students with the same high perception of prevalence of homophobic bullying at their school were equally less likely to tell a teacher, even if one of them was in a school with a high average level of perceived prevalence and the other in a school with low perceived prevalence, which denotes that individual perception about prevalence is of greater relevance for students to approach teachers than school level perceptions.

Limitations

As with any cross-sectional study, our analysis could only explore associations between variables and does not pretend to inference causality.

One limitation of our study was our inability to add those who identified as other gender to the sample, and to conduct further analysis on the experiences of this sub-group. Whilst this was due to the lack of data across all the relevant variables used in the analysis, and whilst this group was small (38), it would be of particular interest to learn from their perspective and experiences, and ideally further research should be conducted to do so.

Another limitation occurs in relation to our finding which showed significant differences between schools in the levels of student/teacher connectedness, and the associated likelihood of believing teachers to be a viable source of help. More research is needed to understand the factors that lead students to experience a less supportive relational culture in some schools than in others and the ways in which these factors might intersect with or respond to school initiatives around promotion of respectful relationships.

Discussion and implications

Young people are more likely to experience homophobic harassment at school than in any other location (Hillier et al., 2010), with significant negative impacts for both LGBTIQ + as well as heterosexual or cisgender students. Our study explored peer intentions to report responses to a very common form of homophobic harassment: witnessing students calling male students gay in a derogatory way. It found that 58% of students in our sample reported hearing boys calling other boys gay or saying that they were like a girl more than once during the last week at school. It is important for teachers to be aware of the levels and nature of homophobic harassment that occur in their school, so that they are motivated and informed in their responses. Awareness of the prevalence of bias-based harassment is key to mobilising teacher support for proactive prevention and response strategies to be put in place (Kolbert et al., 2015).

Our study was particularly interested in exploring the school level characteristics that may be associated with the likelihood of students reporting peer homophobic name-calling. It found that positive school level, as well as individual level perceptions of student connectedness to teachers was associated with a higher inclination towards using teachers as a source of help on behalf of classmates. By using individual and school level variables of student–teacher connectedness, we demonstrated the extent to which caring environments at the school level influence student intention to seek help from a teacher. This finding was consistent with more generic bullying prevention research which has demonstrated that students who perceived that their teachers will both intervene to directly address the bullying as well as to support the person who has been targeted are more likely to report instances of interpersonal violence, in this indicating the importance of observable teacher response in generating student belief that teachers care (Demol et al., 2020).

The variance we found between schools in the quality of student/teacher relationships suggested that school supportive relations are amenable to change, with some schools showing evidence of creating more supportive peer and teacher relationships than others, and in turn providing environments in which students were more likely to intend to report homophobic harassment. In addition, the variance in perceived prevalence of homophobic name calling between schools also indicated that these practices are amenable to change, and that school-wide approaches can be harnessed to clearly transmit the message that this form of harassment will not be tolerated.

Our findings support evidence that positive teacher-student relationships promote student wellbeing and are associated with higher likelihood that students will use peers and teachers as a source of help in response to instances of violence (Eliot et al., 2010). They also highlight the important contribution that supportive and inclusive relational climates make in terms of student engagement and participation (M. Holfve-Sabel, 2014; Johnson, 2008; Klem & Connell, 2004; Roorda et al., 2011). Importantly, our findings suggest that above and beyond the effects of independent relationships between student and teachers, school environments of care and support are important to reduce the acceptability and prevalence of homophobic harassment. By building environments of respect, care and support, schools can offer safe contexts for students to feel comfortable to report occurrences of homophobic name-calling, independent of the quality of individual student relationships with teachers. In other words, school cultures where teachers are perceived to care, respect and treat students fairly are better equipped to intervene against homophobic name-calling, despite the individual experience students may have with their respective teachers.

Of concern is the finding that students who perceived that homophobic name-calling was common in their school were less likely to intend to approach a teacher in case of witnessing a student being called gay than students who felt that homophobic name-calling was less common in their school. This may reflect a situation in which due to the widespread nature of this practice, students deduce that teachers and the school as an institution will not take a strong stand against this form of harassment, or that they may be unlikely to respond in a helpful way. This finding adds weight to the importance of investing in school-wide policy, curriculum and behaviour management approaches to prevent all forms of gender-based violence, including homophobic harassment. It also indicates the importance of schools collecting and responding to data about the extent to which students perceive that teachers in the school are caring and supportive, and would respond in proactive and helpful ways to reports of violence.

Narrow masculinity norms have been found to constrain help-seeking as a viable response and certain masculinity norms can work to excuse or even endorse homophobic practices (Gorski, 2010). Our study showed that girls were more likely than boys to indicate a willingness to seek help on behalf of a victimised peer. Bullying research in secondary schools has also demonstrated this gender discrepancy, and has also found that the presence of a supportive culture in the school is particularly important in encouraging help-seeking on the part of males, with smaller gender differences in attitudes towards reporting violence in the more supportive schools (Eliot et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings indicate that male students may perceive a greater degree of social risk in relation to reporting peer-perpetrated harassment. This may be why they particularly benefit from surrounding positive norms in relation to expressions of care within the school community. These norms may play a key role both in providing reassurance about likely helpful response, and via modelling of positive and inclusive relationships.

Overall, this research suggests that investment in building positive student–teacher relationships and creating a school-wide culture of care might be pivotal within efforts to prevent all forms of homophobic and gender-based harassment. Further research into the nexus between school culture, and gender and peer norms relating to expressions of care may contribute insight into the ways in which school policies, practices and curriculum might model and support respectful and inclusive befriending between all students, regardless of gender and orientations.

References

Allen, L. (2018). Reconceptualising homophobia: by leaving ‘those kids’ alone. Discourse Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1495617

Berger, C., Poteat, V. P., & Dantas, J. (2019). Should I report? The role of general and sexual orientation-specific bullying policies and teacher behavior on adolescents’ reporting of victimization experiences. Journal of School Violence, 18(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1387134

Birkett, M., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Homophobic name-calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents. Social Development, 24(1), 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12085

Cahill, H., Beadle, S., Higham, L., Meakin, C., Farrelly, A., Crofts, J., & Smith, K. (2016). Resilience, rights and respectful relationships: Level 7–8 (Vol. Level 7–8). http://fuse.education.vic.gov.au/ResourcePackage/ByPin?pin=2JZX4R

Cahill, H., & Dadvand, B. (2020). Triadic labour in teaching for the prevention of gender-based violence. Gender and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1722070

Cahill, H., Kern, P., Dadvand, B., Walter-Cruickshank, E., Midford, R., Smith, C., . . . Oades, L. (2019). An integrative approach to evaluating the implementation of social and emotional learning and wellbeing education in schools. International Journal of Emotional Education 11(1), 135–152.

Collier, K. L., Bos, H. M., & Sandfort, T. G. (2013). Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9823-2

D’Augelli, A. R., Pilkington, N. W., & Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854

Dadvand, B., & Cahill, H. (2020). Structures for care and silenced topics: Accomplishing gender-based violence prevention education in a primary school. Pedagogy, Culture and Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2020.1732449

Demol, K., Verschueren, K., Salmivalli, C., & Colpin, H. (2020). Perceived teacher responses to bullying influence students’ social cognitions. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.592582

Eliot, M., Cornell, D., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2010). Supportive school climate and student willingness to seek help for bullying and threats of violence. Journal of School Psychology, 48(6), 533–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.07.001

Espelage, D. L., Basile, K. C., Leemis, R. W., Hipp, T. N., & Davis, J. P. (2018). Longitudinal examination of the bullying-sexual violence pathway across early to late adolescence: Implicating homophobic name-calling. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 47(9), 1880–1893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0827-4

Fulcher, K. (2017). That’s so homophobic? Australian young people’s perspectives on homophobic language use in secondary schools. Sex Education, 17(3), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1275541

Goldweber, A., Waasdorp, T., & Bradshaw, C. (2013). Examining the link between forms of bullying behaviors and perceptions of safety and belonging among secondary school students. Journal of School Psychology, 51(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.04.004

Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 3, 21–43

Gorski, E. (2010). Stoic, stubborn, or sensitive: How masculinity affects men’s help-seeking and help-referring behaviors. UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research, XIII, 1–6.

Gregory, A., & Cornell, D. (2009). “Tolerating” adolescent needs: Moving beyond zero tolerance policies in high school. Theory into practice, 48(2), 106-113

Gregory, A., & Weinstein, R. S. (2004). Connection and regulation at home and in school: Predicting growth in achievement for adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 405–442

Gregory, A., Cornell, D., Fan, X., Sheras, P., Shih, T. H., & Huang, F. (2010). Authoritative school discipline: High school practices associated with lower bullying and victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 483

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children's school outcomes through eighth grade. Child development, 72(2), 625-638

Hillier, L., Jones, T., Monagle, M., Overton, N., Gahan, L., Blackmen, J., & Mitchell, A. (2010). Writing themselves in 3 (WTi3): The third national study on the sexual health and wellbeing of same sex attracted and gender questioning young people (1921377925). Retrieved from Melbourne, Australia. https://hdl.handle.net/1959.11/10504

Holfve-Sabel, M.-A. (2014). Learning, interaction and relationships as components of student well-being: Differences between classes from student and teacher perspective. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1535–1555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0557-7

Kern, P., Cahill, H., Morrish, L., Farrelly, A., Shlezinger, K., & Jach, H. (2020). The responsibility of knowledge: Identifying and reporting students with evidence of psychological distress in large-scale school-based studies. Research Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016120952511

Kolbert, J. B., Crothers, L. M., Bundick, M. J., Wells, D. S., Buzgon, J., Berbary, C., . . . Senko, K. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions of bullying of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning (LGBTQ) students in a Southwestern Pennsylvania Sample. Behavioural Science (Basel), 5(2), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs5020247

Kosciw, J., Greytak, E., Palmer, N., & Boesen, M. (2014). The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Bartkiewicz, M. J., Boesen, M. J., & Palmer, N. A. (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

Maehr, M. L. (1991). The “psychological environment” of the school: A focus for school leadership. Advances in Educational Administration, 2, 51–81

McCormack, M. (2011). Mapping the terrain of homosexually-themed language. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(5), 664–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.563665

Merrin, G. J., De La Haye, K., Espelage, D. L., Ewing, B., Tucker, J. S., Hoover, M., & Green, H. D. (2018). The co-evolution of bullying perpetration, homophobic teasing, and a school friendship network. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 47(3), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0783-4

Meyer, E. J. (2008). Gendered harassment in secondary schools: Understanding teachers’ (non)-interventions. Gender and Education, 20(6), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802213115

Mitchell, K. J., Ybarra, M. L., & Korchmaros, J. D. (2014). Sexual harassment among adolescents of different sexual orientations and gender identities. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38(2), 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.008

O’Donoghue, K., & Guerin, S. (2017). Homophobic and transphobic bullying: Barriers and supports to school intervention. Sex Education, 17(2), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1267003

Poteat, V. P., & Espelage, D. (2007). Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431606294839

Poteat, V. P., Mereish, E. H., DiGiovanni, C. D., & Koenig, B. W. (2011). The effects of general and homophobic victimization on adolescents’ psychosocial and educational concerns: The importance of intersecting identities and parent support. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 597. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025095

Poteat, V. P., & Russell, S. T. (2013). Understanding homophobic behavior and its implications for policy and practice. Theory into Practice, 52(4), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.829729

Poteat, V. P., Sinclair, K. O., DiGiovanni, C. D., Koenig, B. W., & Russell, S. T. (2013). Gay–straight alliances are associated with student health: A multischool comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00832.x

Rasmussen, M. L., Sanjakdar, F., Allen, L., Quinlivan, K., & Bromdal, A. (2017). Homophobia, transphobia, young people and the question of responsibility. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 38(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1104850

Ringrose, J., & Renold, E. (2010). Normative cruelties and gender deviants: The performative effects of bully discourses for girls and boys in school. British Educational Research Journal, 36(4), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903018117

Rivers, I. (2000). Social exclusion, absenteeism and sexual minority youth. Support for Learning, 15(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.00136

Rivers, I., Poteat, V. P., Noret, N., & Ashurst, N. (2009). Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly, 24(4), 211.

Russell, S. T., Day, J. K., Ioverno, S., & Toomey, R. B. (2016). Are school policies focused on sexual orientation and gender identity associated with less bullying? Teachers’ perspectives. Journal of School Psychology, 54, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.10.005

Swearer, S. M., Turner, R. K., Givens, J. E., & Pollack, W. S. (2008). “You’re so gay!”: Do different forms of bullying matter for adolescent males? School Psychology Review, 37(2), 160–173.

Thompson, J. D. (2019). Predatory schools and student non-lives: A discourse analysis of the Safe Schools Coalition Australia controversy. Sex Education, 19(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1475284

Waasdorp, T., Pas, E., O’Brennan, L., & Bradshaw, C. (2011). A multilevel perspective on the climate of bullying: Discrepancies among students, school staff, and parents. Journal of School Psychology, 10(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.539164

Wernick, L. J., Kulick, A., & Inglehart, M. H. (2013). Factors predicting student intervention when witnessing anti-LGBTQ harassment: The influence of peers, teachers, and climate. Children Youth Services Review, 35(2), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.11.003

Yablon, Y. B. (2010). Student–teacher relationships and students’ willingness to seek help for school violence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(8), 1110–1123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510381255

Funding

This project was funded by an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant #LP160100428 (Helen Cahill Principal Investigator), with industry partners the Department of Education and Training Victoria and VicHealth Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molina, A., Shlezinger, K. & Cahill, H. Asking for a friend: seeking teacher help for the homophobic harassment of a peer. Aust. Educ. Res. 50, 481–501 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00492-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00492-2