Abstract

Progress in treatments has led to HIV+ patients getting older. Age and HIV are risk factors for neurocognitive impairment (NCI). We explored the role of cognitive reserve (CR) on cognition in a group of virologically suppressed older HIV+ people. We performed a multicenter study, consecutively enrolling asymptomatic HIV+ subjects ≥60 years old during routine outpatient visits. A comprehensive neuropsychological battery was administered. Raw test scores were adjusted based on Italian normative data and transformed into z-scores; NCI was defined according to Frascati criteria. All participants underwent the Brief Intelligence Test (TIB) and the Cognitive Reserve Index (CRI) questionnaire as proxies for CR. Relationships between TIB, CRI, and NCI were investigated by logistic or linear regression analyses. Sixty patients (85 % males, median age 66, median education 12, 10 % HCV co-infected, 25 % with past acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining events, median CD4 cells count 581 cells/μL, median nadir CD4 cells count 109 cells/μL) were enrolled. Twenty-four patients (40 %) showed Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment. At logistic regression analysis, only CRI (OR 0.94; 95 % CI 0.91–0.97; P = 0.001) and TIB (OR 0.80; 95 % CI 0.71–0.90; P < 0.001) were associated with a lower risk of NCI. Higher CRI and TIB were significantly correlated with a better performance (composite z-score) both globally and at individual cognitive domains. Our findings highlight the role of CR over clinical variables in maintaining cognitive integrity in a virologically suppressed older HIV-infected population. A lifestyle characterized by experiences of mental stimulation may help to cope aging and HIV-related neurodegeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Progress in antiretroviral treatment has given the chance to those living with HIV to get older. Recent data shows that elders represent 17.7 % of new HIV diagnoses and 33.3 % of those living with HIV (Linee Guida Italiane sull’utilizzo dei farmaci antiretrovirali e sulla gestione diagnostico-clinica delle persone con infezione da HIV-1. Available at: www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17pubblicazioni_2261_allegato.pdf).

As people age with HIV, they are at greater risk to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), which can interfere with everyday functioning, medical decision making, and quality of life (Antinori et al. 2007; Valcour et al. 2004). Since the introduction of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART), several groups have reported a reduction in the overall incidence of the most severe forms of HAND, which, however, continue to affect HIV-infected population. The current diagnostic categories of HAND recognize three conditions: asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND), and HIV-associated dementia (HAD), the most severe form. Overall, the prevalence of HAND based on current criteria is approximately 50–60 % (Antinori et al. 2007; Heaton et al. 2010).

Studies of cognitive aging in HIV-uninfected subjects demonstrated a clear relationship between age-related reductions in white matter integrity and the consequent decline on tests of processing speed, episodic memory, and executive functions (Gunning-Dixon et al. 2009). Older HIV-infected subjects with neurocognitive impairment (NCI) appeared to have greater deficits in executive functioning, probably due to an increased prevalence of cerebrovascular disease (Valcour et al. 2011).

Despite both HIV status and age are risk factors for cognitive decay, not all elders with HIV showed the expected cognitive decline (Valcour et al. 2004). Some authors have recently observed a 32 % prevalence of successful cognitive ageing in a cohort of older HIV-infected people, defined as “the absence of neurocognitive decay as measured by both performance-based tests and self-report of cognitive difficulties in daily life” (Malaspina et al. 2011). These findings suggested that at least one third of older individuals with HIV were able to evade even the mildest forms of HAND (Malaspina et al. 2011).

Previous studies reported the role of cognitive reserve (CR), defined as the ability to make flexible and efficient use of cognitive networks when performing tasks, to the maintenance of neuropsychological integrity in HIV-infected people (Basso et al. 2000; Satz et al. 1993; Stern et al. 1996; Stern 2002). Such a definition of CR implies that the brain actively attempts to compensate or cope for brain damage (Stern 2002, 2013). CR might help to understand individual differences in clinical resilience to brain pathology.

CR has been investigated in several contexts: Alzheimer’s disease, normal aging, vascular injury, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, neuropsychiatric disorders, and multiple sclerosis (Elkins et al. 2006; Dufouil et al. 2003; Glatt et al. 1996; Kesler et al. 2003; Barnett et al. 2006; Sumowski et al. 2010).

With regard to older HIV-infected population, recent findings have highlighted the importance of a high CR in protecting against cognitive decline due to HIV status as well as the aging process. A study showed that a significant proportion of older HIV-infected subjects (57/102, 56 %) was cognitively unimpaired despite the high risk for compromise, due to the higher CR of this group of subjects than other subgroups included in the study (Foley et al. 2012). In another work, the CR was found to be the most robust predictor of neurocognition (Patel et al. 2013). Finally, while the HIV-uninfected subjects and HIV-infected people with normal cognition were able to compensate for the age-related decline, older HAND subjects were unable to fully compensate or activate the reserve network, thus resulting in cognitive impairment (Chang et al. 2013).

In the abovementioned studies, the mean age for the older group of patients was around 50 years, which in HIV research has been traditionally used as the cutoff for groups defined as “old” (Foley et al. 2012; Patel et al. 2013; Chang et al. 2013; Wendelken and Valcour 2012). However, currently, the inclusion of individuals over age 60 rather than 50 would be more representative of the current population of people living with HIV, considering longer lifespan due to cART and older age at seroconversion. Furthermore, factors related to the severity of HIV infection such as current and nadir CD4 cell count, plasma viral load, and time from HIV diagnosis may impact neurocognitive functioning.

Given these considerations, the target population of the current study was selected to minimize the potential confounder effects of the abovementioned variables and to better explore the role of protective mechanisms other than clinical conditions in a sample of seropositive adults at greater risk for HAND. Particularly, in this study, we sought to examine the role of CR over clinical variables in maintaining optimal neuropsychological functioning among a viro-immunologically controlled group of HIV-infected subjects over 60 years of age.

Methods

Participants

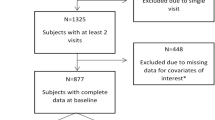

Asymptomatic HIV-infected participants, with no active opportunistic diseases, acute infections, or other acute medical conditions, were recruited from September 2014 to February 2015 during regular outpatient follow-up in three clinical centers (Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome; S. Caterina Novella Hospital, Galatina and Siena University Hospital, Siena). All participants were required to sign informed consent prior to enrollment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: age <60 years, active or past central nervous system (CNS) opportunistic infections, history of neurological disorders, active psychiatric disorders and alcoholism or drug abuse, and HIV-RNA >50 copies/mL (see also Fabbiani et al. 2013). Subjects were also required to be Italian speaking.

Data on the following demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables were collected for each participant at the time of neuropsychological testing: sex, age, education, risk factors for HIV infection, time from HIV diagnosis, co-infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining events, current antiretroviral regimen, CD4 cell count, CD4 cell count nadir, and HIV-1 viral load. History of diabetes (defined as fasting glucose plasma levels >126 mg/dL and/or treatment with glucose-lowering agents), hypertension (defined as blood pressure >140/90 mmHg and/or treatment with antihypertensive medications), and dyslipidemia (defined as low-density lipoprotein (LPL) cholesterol levels ≥130 mg/dL and/or treatment with lipid-lowering drugs) was collected as well (see also Fabbiani et al. 2013; National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) 2002).

CNS penetration-effectiveness (CPE) rank was calculated for each antiretroviral regimen according to the CHARTER group criteria revised in 2010 (Letendre et al. 2010). Antiretroviral regimens showing a CPE rank ≥6 were considered effective in the treatment of CNS infection (Ciccarelli et al. 2013).

Neuropsychological examination

All participants underwent an extensive neuropsychological evaluation exploring multiple cognitive domains: memory, language, attention and executive functions, fine motor skills, and working memory. Participants completed the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale to evaluate for depressed symptoms, whereas the Instrument Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale was used to assess everyday functioning.

When the score on each cognitive test was below the age-, gender- and education-adjusted normative cutoff, we classified the performance as impaired.

According to HAND criteria, subjects were diagnosed as cognitively impaired if the decreased cognitive function involved at least two ability domains among those assessed: the profiles of ANI, MND, and HAD were differentiated on the basis of the severity of NCI and its impact on everyday life activities (Antinori et al. 2007).

For each cognitive test, raw scores were transformed into z-scores using means and standard deviations of Italian normative data (Capitani et al. 1997; Carlesimo et al. 1996). Finally, global cognitive performance was obtained by calculating a composite z-score consisted of the average of single z-score on each test.

CR factors

The factors thought to maintain or improve CR include premorbid intelligence and intellectual experiences throughout the lifespan (i.e., education, occupational achievement, and engagement in leisure activities) (Stern 2002). In order to assess and quantify the amount of CR for each subject, all participants of this study underwent (i) the Cognitive Reserve Index (CRI) questionnaire for the measurement of the quantity of CR accumulated by individuals throughout their lifespan and (ii) the Brief Intelligence Test (TIB), found to be correlated with intelligence quotient (IQ) (Nucci et al. 2011; Colombo et al. 2002).

The CRI questionnaire includes demographic data and items grouped into three sections: education, working activity, and leisure time, each of which returns a subscore (Nucci et al. 2011). By administering this instrument, four different subscores are derived: CRI-total score, CRI-education, CRI-working activity, and CRI-leisure time. A score performance ≤70 at CRI is classified as abnormal (Nucci et al. 2011).

Instead, the TIB test, an Italian version of the National Adult Reading Test (NART), requires the subject to read out a list of Italian words with a dominant (regular) and a less frequent (irregular) stress pattern (Colombo et al. 2002). Performance on the TIB provides a good estimate of premorbid intelligence, allowing to obtain a general score (TIB-total score) from the numbers of errors made by the subject and to estimate verbal and performance IQ (TIB-verbal and TIB-performance). Scores <93.1 at TIB indicate a pathological performance (Colombo et al. 2002).

Intelligence is often used as a CR proxy due to the correlation between IQ and CR, even though some authors argued that they are not necessarily overlapping factors in terms of what they really measure. While the IQ is a measure of performance, CR represents the cognitive abilities acquired and gathered over a lifetime (Nucci et al. 2011). Thus, in the current study using the CRI and TIB as proxies for CR, we were able to take into account all the factors thought to be strongly correlated with CR and to explore their individual associations with neuropsychological performance. Although education is used in some studies as a good estimate for CR either alone or in association with other variables, the CRI questionnaire allows to get a subscore for education. Therefore, we preferred to include the CRI-education subscore rather than years in school in our analyses.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for quantitative variables [mean, standard deviation (±SD), 95 % confidence intervals (CIs), median, interquartile range (IQR)], and qualitative variables (absolute and percent frequencies).

We performed logistic regression analyses to explore the association between any demographic and clinical variable with NCI, while we ran linear regression analyses to identify factors associated with global cognitive performance (as measured by the composite z-score) or with cognitive performance on each domain (as measured by the z-score of each domain).

Variables showing a significant P value in univariate analysis were further investigated either in bivariate analysis models when the collinear relationship between the predictors was a concern or in multivariate analysis when appropriate.

P value was set at 0.05 for level of significance. All analyses were performed using the SPSS Version 13.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 60 subjects were enrolled in this study; their main demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 60 participants, 85 % (n = 51) were male and the median scores for age and education were 66 and 12 years, respectively. Most of the participants (52 %, n = 31) had been infected through heterosexual contact.

At the time of testing, all patients were on cART, of which 35 (58.3 %) were on protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimens, 17 (28.4 %) were on nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based regimen, and 8 (13.3 %) were on other combinations. The median current CD4 count was 581 cells/μL, while the median nadir CD4 count was 109 cells/μL. Six subjects (10 %) were co-infected with HCV.

Neuropsychological performance

Overall, 24 patients (40 %) were classified as being affected by NCI, all showing a profile of ANI; none of the patients revealed a cognitive profile of MND or HAD.

Results of the neuropsychological performances in each test are shown in Table 2. A higher proportion of pathological performances was observed in multiple features target cancellation (MFTC) test either false positive (27 %, n = 16) or accuracy (24 %, n = 14), digit span (18 %, n = 11), and grooved pegboard for dominant (17 %, n = 10) and nondominant (16 %, n = 9) hand.

Nine (15 %) and 7 (12 %) subjects showed a pathological performance on the Rey auditory verbal learning test (RAVLT) immediate and delayed recall, respectively; finally, 7 (12 %) patients scored poorly on the WAIS digit symbol.

Overall, mean Zung Depression Scale score was 34.4 (±7.4): 14 subjects (23 %) obtained a borderline score (40–49), while only one subject got a frank pathological score ≥50. On functional evaluation, IADL score was at ceiling for all (8/8).

CR’s estimate

The median CRI-total score was 114 (IQR 96.2–132.5), while the median scores on CRI-education, CRI-working activity, and CRI-leisure time were 106.5 (IQR 92.5–118), 108.5 (IQR 98.2–123.5), and 115.5 (IQR 93.2–135.5), respectively. Only one patient (2 %) obtained a CRI-total score lower than the suggested cutoff (i.e., ≤70). Analyzing the CRI-total score by cognitive status, we found that the mean value was 100 (±19.5) for those participants affected by ANI and 124 (±21.8) for cognitively unimpaired subjects (P < 0.001).

Regarding the performance at TIB, the median value was 112.6 (IQR 104.7–117.6) for TIB-total score, 110 (IQR 103.2–116.2) for TIB-verbal, and 114.4 (IQR 106.2–117.9) for TIB-performance. Finally, the mean of errors made at TIB was 6.3 (±7.2). Six patients (10 %) showed a poor performance at TIB (i.e., <93.1). Comparing ANI versus cognitively normal participants, the mean scores were 102 (±11.3) and 115 (±4.5), respectively (P < 0.001). We also found a significant difference between ANI (12.4; ±7.9) and unimpaired (2.2; ±2.3) participants for number of errors at TIB (P < 0.001).

Factors associated with cognitive impairment

Factors associated with NCI were identified by univariate and bivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Univariate analysis showed that longer education, higher CRI (total score, working activity, and leisure time subscores), and TIB score (total score, verbal and performance subscores) were associated with a lower risk to be diagnosed with NCI, while older age and higher number of errors at TIB were associated with a higher risk (P < 0.05).

We could not enter the variables resulted significantly associated with NCI at univariate analysis in a multivariate model due to the collinearity issue between our primary predictors: CRI and TIB (r s = 0.72, P < 0.001). However, we performed different sets of bivariate analyses each including age and every different variable resulted significantly associated with NCI at the univariate analysis. In all the analyses, older age confirmed to be independently associated with a greater risk to develop HAND (see Table 3 for the statistics of age in each bivariate model) except when age was entered in the bivariate analysis with the number of errors at TIB. In this latter model, only the number of errors at TIB (adjusted odd ratio (aOR) 1.54 per one error more, 95 % CI 1.20–1.97, P = 0.001) was significantly correlated with greater risk of cognitive decline.

Higher CRI-total score (aOR 0.93, 95 % CI 0.89–0.97, P < 0.001), CRI-education (aOR 0.87, 95 % CI 0.82–0.94, P < 0.001), and CRI-leisure time (aOR 0.93, 95 % CI 0.90–0.96, P < 0.001), as well as TIB-total score (aOR 0.77, 95 % CI 0.67–0.89, P < 0.001), TIB-verbal (aOR 0.77, 95 % CI 0.67–0.89, P < 0.001), and TIB-performance (aOR 0.77, 95 % CI 0.66–0.89, P < 0.001), confirmed to be independently associated with HAND diagnosis after adjusting for age.

Variables related to the severity of HIV infection or, in general, factors with a documented impact on cognitive functioning (current and nadir CD4 cell count, time from HIV diagnosis, HCV co-infection, time from ART current regimen start, CPE rank) were not found to be associated with NCI.

Lastly, unlikely other studies which have documented a relationship between depression and neurocognitive deficits, we did not observe a significant association between mood status and NCI, probably due the low number of subjects with a frank pathological score at the Zung scale (Castellon et al. 2006; Cole et al. 2007).

Factors associated with neuropsychological performance

Factors influencing global cognitive performance as measured by composite z-score were investigated by linear regression analysis. In univariate analysis, higher educational level (β 0.50, 95 % CI 0.06–0.17, P < 0.001) and higher scores on CRI-total (β 0.39, 95 % CI 0.01–0.03, P = 0.002), CRI-education (β 0.51, 95 % CI 0.02–0.04, P < 0.001), CRI-leisure time (β 0.36, 95 % CI 0.01–0.03, P = 0.005), TIB-total (β 0.52, 95 % CI 0.03–0.07, P < 0.001), TIB-verbal (β 0.53, 95 % CI 0.03–0.07, P < 0.001), and TIB-performance (β 0.51, 95 % CI 0.03–0.07, P < 0.001) were associated with better neuropsychological performance, while a greater number of errors at TIB (β −0.55, 95 % CI −0.10/−0.04, P < 0.001) was associated with worse performance. As previously stated, we could not perform a multivariate analysis due to the high correlation among main variables.

In order to investigate the factors impacting on each cognitive domain, we ran univariate linear analyses (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the supplementary material for factors associated with neuropsychological performance in each cognitive domain). In general, the findings confirmed the impact of CR as measured by CRI and TIB on all the domains explored. However, we found independent significant associations between lower CRI-total score (mean change in z-score 0.31, 95 % CI 0.00–0.01, P = 0.012), diabetes (mean change in z-score −0.29, 95 % CI −0.67/−0.07, P = 0.016), and older age (mean change in z-score −0.33, 95 % CI −0.05/−0.01, P = 0.007) with worse performance in the working memory domain and between all the scores on TIB (mean change in z-score 0.27, 95 % CI 0.00–0.11, P < 0.05) and younger age (mean change in z-score −0.28, 95 % CI −0.19/−0.01, P = 0.028) with fine motor skills.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the impact of CR on cognition among a sample of HIV-infected people aged 60 and older with a good viro-immunological control, using CRI and TIB measures as proxies for skills acquired over a lifetime and premorbid intelligence, respectively.

Our findings confirmed that CR represents a resilience factor against cognitive decline in a group of virologically suppressed older HIV-infected patients.

Nevertheless, we found that 40 % of subjects were affected by HAND, all showing an ANI profile according to standard criteria, providing further evidence that HAND remains an important complication even in the cART era, despite the decreased incidence of HAD as a natural outcome of therapy (Antinori et al. 2007; Heaton et al. 2010; Tozzi et al. 2007; Sacktor et al. 2001).

With the prolonged life expectancy of individuals with HIV, age is also a factor which may contribute to the prevalence and severity of HAND (Valcour et al. 2004). Indeed, we found that older age was independently associated with greater risk of NCI and with worse performance in the working memory and motor domains. On the other hand, 60 % of the subjects enrolled in our study were cognitively normal. Unimpaired participants were also those subjects who scored better on CRI and TIB measures, which resulted significantly correlated with neuropsychological performance as measured by global z-score.

None of the factors related to the severity of HIV infection (current and nadir CD4 cell count, time from HIV diagnosis, HCV co-infection, time from ART current regimen start, CPE rank) was found to be associated with NCI (Hammond et al. 2014; Fabbiani et al. 2014).

The effect of CR (as measured by both CRI and TIB tests) was greater on the domains of episodic memory, attention, and language when compared to the working memory and motor speed areas. For these latter domains, we also found significant relationships between age and diabetes with working memory performance and between older age with a worse performance on motor speed. According to previous evidences, our study provided further evidence that increased age is a risk factor for cognitive changes in executive and psychomotor speed performance (Sacktor et al. 2007).

Several studies focusing on CR in the HIV context reported the specific role of CR in protecting against neuropsychological dysfunction in early HIV infection (Glatt et al. 1996; Pereda et al. 2000). Recently, some authors examined whether CR might explain vulnerability to syndromic forms of HAND and found that subjects affected by MND or HAD evidenced lower reserve scores when compared to ANI or cognitively unimpaired HIV-infected patients (Morgan et al. 2012). However, we could not better explore this hypothesis in this study because all cognitively impaired participants showed an ANI profile. The difference across studies in the estimated prevalence of each HAND category may reflect either differences in the cohort studied or the neuropsychological battery used but may be also due to the inclusion criteria for enrollment in the current study.

Among the few works that addressed the role of CR in elders with HIV, one found that age was not significantly predictive of cognition, while the CR continued to account for most of the variance in cognitive functioning (Patel et al. 2013). In another one, the HIV-infected subjects with the greatest number of risk factors (i.e., HIV status and older age) for cognitive decline but who remained cognitively unimpaired also showed the highest level of CR when compared to other groups with varying levels of risk factors (Foley et al. 2012). In this light, our findings confirmed the relevant impact of CR on cognition among older virologically suppressed patients, suggesting that a higher CR could provide people with skills and abilities, which may help them to cope with neurodegeneration related to the HIV status and to aging process itself.

It has been hypothesized that the noradrenergic system represents a possible neural network, which may contribute to CR. Growing evidence indicates that noradrenaline may mediate between reserve and reduced risk of diagnosis of AD (Wilson et al. 2013; Robertson 2013). Repeated noradrenergic activation over a lifespan may enhance brain reserve through mechanisms such as synaptogenesis and neurogenesis or by protecting other neurotransmitter systems like dopamine (Robertson 2013). CR markers such as education, occupational complexity, and premorbid intelligence activate the brain’s noradrenaline system and are likely to contribute to increased brain reserve through a well-connected set of networks better able to function in the presence of pathology. In addition, noradrenaline activity may also facilitate networks for arousal, novelty, attention, awareness, and working memory, which provide for a set of additional, cognitive mechanisms that help the brain to adapt to age-related changes and disease (Robertson 2013, 2014). Even if further investigations are needed to explore this hypothesis in the context of HIV, the neuroprotective effects of the noradrenergic system mediated by environmental enrichment make this hypothesis a viable one in the effort of elucidating the biological mechanism of CR.

We acknowledge that our study might have some limitations because uncontrolled biases can occur in cross-sectional surveys performed in routine clinical practice. Thus, future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the findings and to better clarify the impact of CR on cognitive functioning in elders with HIV. Further, we must note our lack of a control group as a limitation to this study. Lastly, our sample was comprised predominantly of men (85 %, n = 51), which might limit generalizability of results, given also the gender effect found to affect the CRI questionnaire (Nucci et al. 2011). On the other hand, this study had important strengths. Among these, there was the enrollment of subjects aged 60 and above, which is more representative of the current HIV-infected population. Moreover, all the subjects had achieved a good viro-immunological control at the time of the assessment.

In conclusion, according to the CR theory, the richer the life a person has had in terms of cognitively challenging experiences or abilities, the more that person will be able to cope with cognitive dysfunction derived from a certain brain pathology by using pre-existing cognitive processes or enlisting compensatory strategies (Stern 2002). The findings of this study suggest that higher CR may protect against negative effects of aging- and HIV-related neurodegeneration in a group of virologically suppressed older HIV-infected subjects. In clinical settings, CR may help to identify patients at greater risk for HAND. Encouraging factors associated with CR throughout the lifespan may allow a greater number of people living with HIV to age successfully, which in turn may have a positive impact on their quality of life and reduce the burden on caregivers and health care system.

References

Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VEJT (2007) Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 69:1789–1799

Barnett JH, Salmond CH, Jones PB, Sahakian BJ (2006) Cognitive reserve in neuropsychiatry. Psychol Med 36:1053–1064

Basso MR, Bornstein RA (2000) Estimated premorbid intelligence mediates neurobehavioral change in individuals infected with HIV across 12 months. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 22:208–218

Capitani E, Laiacona M (1997) Composite neuropsychological batteries and demographic correction: standardization based on equivalent scores, with a review of published data. The Italian group for the neuropsychological study of ageing. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 19:795–809

Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Gainotti G (1996) The mental deterioration battery: normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. The group for the standardization of the mental deterioration battery. Eur Neurol 36:378–384

Castellon SA, Hardy DJ, Hinkin CH, Satz P, Stenquist PK, van Gorp WG, Myers HF, Moore L (2006) Components of depression in HIV-1 infection: their differential relationship to neurocognitive performance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 28:420–437

Chang L, Holt JL, Yakupov R, Jiang CS, Ernst T (2013) Lower cognitive reserve in the aging human immunodeficiency virus-infected brain. Neurobiol Aging 34:1240–1253. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.012

Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Colafigli M, Trecarichi EM, Silveri MC, Cauda R, Murri R, De Luca A, Di Giambenedetto S (2013) Revised central nervous system neuropenetration-effectiveness score is associated with cognitive disorders in HIV-infected patients with controlled plasma viraemia. Antivir Ther 18:153–160. doi:10.3851/IMP2560

Cole MA, Castellon SA, Perkins AC, Ureno OS, Robinet MB, Reinhard MJ, Barclay TR, Hinkin CH (2007) Relationship between psychiatric status and frontal-subcortical systems in HIV-infected individuals. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 13:549–554

Colombo L, Sartori G, Brivio C (2002) Stima del quoziente intellettivo tramite l’applicazione del TIB (Test Breve di Intelligenza). G Ital Psicol 613–638

Dufouil C, Alperovitch A, Tzourio C (2003) Influence of education on the relationship between white matter lesions and cognition. Neurology 60:831–836

Elkins JS, Longstreth WT Jr, Manolio TA, Newman AB, Bhadella RA, Johnston SC (2006) Education and the cognitive decline associated with MRI-defined brain infarct. Neurology 67:435–440

Fabbiani M, Ciccarelli N, Tana M, Farina S, Baldonero E, Di Cristo V, Colafigli M, Tamburrini E, Cauda R, Silveri MC, Grima P, Di Giambenedetto S (2013) Cardiovascular risk factors and carotid intima-media thickness are associated with lower cognitive performance in HIV-infected patients. HIV Med 14:136–144. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01044.x

Fabbiani M, Grima P, Milanini B, Mondi A, Baldonero E, Ciccarelli N, Cauda R, Silveri MC, De Luca A, Di Giambenedetto S (2014) Antiretroviral neuropenetration scores better correlate with cognitive performance of HIV-infected patients after accounting for drug susceptibility. Antivir Ther. doi:10.3851/IMP2926

Foley JM, Ettenhofer ML, Kim MS, Behdin N, Castellon SA, Hinkin CH (2012) Cognitive reserve as a protective factor in older HIV-positive patients at risk for cognitive decline. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 19:16–25. doi:10.1080/09084282.2011.595601

Glatt SL, Hubble JP, Lyons K, Paolo A, Tröster AI, Hassanein RE, Koller WC (1996) Risk factors for dementia in Parkinson’s disease: effect of education. Neuroepidemiology 15:20–25

Gunning-Dixon FM, Brickman AM, Cheng JC, Alexopoulos GS (2009) Aging of cerebral white matter: a review of MRI findings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24:109–117. doi:10.1002/gps.2087

Hammond ER, Crum RM, Treisman GJ, Mehta SH, Marra CM, Clifford DB, Morgello S, Simpson DM, Gelman BB, Ellis RJ, Grant I, Letendre SL, McArthur JC, CHARTER Group (2014) The cerebrospinal fluid HIV risk score for assessing central nervous system activity in persons with HIV. Am J Epidemiol 180:297–307. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu098

Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I, CHARTER Group (2010) HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 75:2087–2096. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727

Kesler SR, Adams HF, Blasey CM, Bigler ED (2003) Premorbid intellectual functioning, education, and brain size in traumatic brain injury: an investigation of the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Appl Neuropsychol 10:153–162

Letendre S, Fitzsimons C, Ellis RJ, Clifford D, Collier AC, Gelman B, Marra C, McArthur J, McCutchan JA, Morgello S, Simpson D, Vaida F, Heaton R, Grant I and the CHARTER Group (2010) Correlates of CSF viral loads in 1,221 volunteers of the CHARTER cohort. 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 16–19 February, San Francisco, CA, USA, Abstract 172

Malaspina L, Woods SP, Moore DJ, Deep C, Letendre SL, Jeste D, Grant I, HIV Neurobehavioral Research Programs (HNRP) Group (2011) Successful cognitive aging in persons living with HIV infection. J Neurovirol 17:110–119. doi:10.1007/s13365-010-0008-z

Morgan EE, Woods SP, Smith C, Weber E, Scott JC, Grant I, HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group (2012) Lower cognitive reserve among individuals with syndromic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). AIDS Behav 16:2279–2285. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0229-7

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (2002) Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation 106:3143–3421

Nucci M, Mapelli D, Mondini S (2011) Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): a new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin Exp Res 24:218–226. doi:10.3275/800

Patel SM, Thames AD, Arbid N, Panos SE, Catellon S, Hinkin CH (2013) The aggregate effects of multiple comorbid risk factors on cognition among HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 35:421–434. doi:10.1080/13803395.2013.783000

Pereda M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Gomez Del Barrio A, Echevarria S, Farinas MC, Garcia Palomo D, Gonzáles Macias J, Vázquez-Barquero JL (2000) Factors associated with neuropsychological performance in HIV-seropositive subjects without AIDS. Psychol Med 30:205–217

Robertson IH (2013) A noradrenergic theory of cognitive reserve: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 34:298–308. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.05.019

Robertson IH (2014) Right hemisphere role in cognitive reserve. Neurobiol Aging 35:1375–1385. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.028

Sacktor N, Lyles RH, Skolasky R, Kleeberger C, Selnes OA, Miller EN, Becker JT, Cohen B, McArthur JC, Multicenter AIDS Cohrt Study (2001) HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes: multicenter AIDS cohort study, 1990–1998. Neurology 56:257–260

Sacktor N, Skolasky R, Selnes OA, Watters M, Poff P, Shiramizu B, Shikuma C, Valcour V (2007) Neuropsychological test profile differences between young and old human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals. J Neurovirol 13:203–209

Satz P, Morgenstern H, Miller EN, Selnes OA, McArthur JC, Cohen BA, Wesch J, Becker JT, Jacobson L, D’Elia LF, van Gorp W, Visscher B (1993) Low education as a possible risk factor for cognitive abnormalities in HIV-1: findings from the multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 6:503–511

Stern RA, Silva SG, Chaisson N, Evans DL (1996) Influence of cognitive reserve on neuropsychological functioning in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Arch Neurol 53:148–153

Stern Y (2002) What is cognitive reserve? theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 8:448–460

Stern Y (2013) Cognitive reserve: implications for assessment and intervention. Folia Phoniatr Logop 65:49–54. doi:10.1159/000353443

Sumowski JF, Wylie GR, Deluca J, Chiaravalloti N (2010) Intellectual enrichment is linked to cerebral efficiency in multiple sclerosis: functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for cognitive reserve. Brain 133:362–374. doi:10.1093/brain/awp307

Tozzi V, Balestra P, Bellagamba R, Corpolongo A, Salvatori MF, Visco-Comandini U, Vlassi C, Giulianelli M, Galgani S, Antinori A, Narciso P (2007) Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits despite long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-related neurocognitive impairment: prevalence and risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 45:174–182

Valcour V, Paul R, Chiao S, Wendelken LA, Miller B (2011) Screening for cognitive impairment in human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 53:836–842. doi:10.1093/cid/cir524

Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, Poff P, Watters M, Selnes O, Holck P, Grove J, Sacktor N (2004) Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii aging with HIV-1 cohort. Neurology 63:822–827

Wendelken LA, Valcour V (2012) Impact of HIV and aging on neuropsychological function. J Neurovirol 18:256–263. doi:10.1007/s13365-012-0094-1

Wilson RS, Nag S, Boyle PA, Hizel LP, Yu L, Buchman AS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA (2013) Neural reserve, neuronal density in the locus ceruleus, and cognitive decline. Neurology 80:1202–1208. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182897103

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all the study’s participants.

Preliminary results of this work were previously presented as poster at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Seattle, Washington, USA, February 23–26, 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No specific funding was received for this study. MF received speakers’ honoraria from Abbott Virology, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Janssen-Cilag. RC has been advisor for Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, and Basel Pharmaceutical, received speakers’ honoraria from ViiV, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Abbott, Gilead, and Janssen-Cilag, and research support from “Fondazione Roma.” SDG received speakers’ honoraria and support for travel meetings from Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, and GlaxoSmithKline. All the other authors declare that they have not conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 87.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milanini, B., Ciccarelli, N., Fabbiani, M. et al. Cognitive reserve and neuropsychological functioning in older HIV-infected people. J. Neurovirol. 22, 575–583 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-016-0426-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-016-0426-7