Abstract

The purpose of the study is to evaluate whether laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy (LPD) is safe and feasible for elderly patients. From December 2015 to January 2019, 142 LPD surgeries and 93 OPD surgeries were performed by the same surgeon in the third affiliated hospital of Soochow University. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we retrospectively collected the date of three defined groups: LPD aged < 70 years (group I, 84 patients), LPD aged ≥ 70 years (group II, 56 patients) and OPD aged ≥ 70 years (group III, 28 patients). Baseline characteristics and short-term surgical outcomes of group I and group II, group II and group III were compared. Totally, 168 patients were included in this study; 100 cases were men; 68 cases were women; mean age was 67.9 ± 9.5 years. LPD does not perform as well in elderly as it does in non-elderly patients in terms of intraoperative blood loss (300.0 (200.0–500.0) ml vs. 200.0 (100.0–300.0) ml, p = 0.003), proportion of intraoperative transfusion (17.9% vs. 6.0%, p = 0.026) and time to oral intake (5.0 (4.0–7.0) day vs. 5.0 (3.0–6.0) day, p = 0.036). Operative time, conversion rate, postoperative stay, and proportion of reoperation, Clavien–Dindo classification, 30-day readmission and 90-day mortality were similar in two groups. In elderly patients, when compared with OPD, LPD had the advantage of shorter time to start oral intake (5.0 (4.0–7.0) day vs. 7.0 (5.0–11.3) day, p = 0.005) but the disadvantage of longer operative time (380.0 (306.3–447.5) min vs. 292.5 (255.0–342.5) min, p < 0.001) and higher hospitalization cost (12447.3 (10,189.7–15,340.0) euros vs. 7251.9 (8994.0–11,717.4) euros, p < 0.001). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of postoperative stay, and proportion of reoperation, Clavien–Dindo classification, 30-day readmission and 90-day mortality. LPD is safe and feasible for elderly people, but we need to consider its high cost and long operative time over OPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy which is thought as the sole potentially curative option in several types of benign and malignant periampullary tumors is still the first choice of pancreatic cancer. With the aging of the world’s population, the proportion of elderly patients receiving the operation will be higher and higher, which will be even more pronounced in China. According to the data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, those aged 65 and above account for 11.9% of the total population by the end of 2018 [1]. However, an older age means poorer health, which brings greater risk of perioperative complications and poorer prognosis, which means there will be increasingly age-related challenges duo to the high incidence of mobility and mortality. Although OPD can be successfully applied to elderly patients in many centers, advanced age was still a risk factor for post-operative complications and mortality [2,3,4].

With the development of laparoscopic instruments and techniques, laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) has been widely used due to its advantages of less intraoperative blood loss, the low incidence of postoperative complications, shorter hospitalization stays and comparable overall survival compared to open pancreaticoduodenectomy (OPD) [5]. One possible reason might be that OPD has obvious disadvantages of adding inflammatory and affecting respiratory movement due to postoperative incision pain [6], which can be avoided by LPD. Thus, LPD may be a potential way to improve perioperative outcomes in elderly patients. However, the elderly patients are more frail, have more cardiopulmonary comorbidities, the long duration of laparoscopic surgery and the effect of pneumoperitoneum pressure may affect the prognosis of surgery. Although a 92-year-old female patient was reported as the oldest patient who underwent LPD for pancreatic head cancer [6], whether LPD is suitable for elderly patients remains controversial. This research aims to explore whether LPD is safe and feasible for elderly patients and its characteristics through a retrospective study of short-term surgical outcomes of patients in a group with mature LPD surgical techniques. At the same time, hospital expenses were compared.

Materials and methods

Information

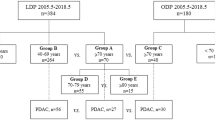

From December 2015 to January 2019, 142 LPD surgeries and 93 OPD surgeries were performed by the same surgeon in the third affiliated hospital of Soochow university (the first people’s hospital of Changzhou). After screening of Inclusion and exclusion criteria, we excluded 2 LPD surgeries and 1 OPD surgeries. To address the research needs, we defined three groups: patients < 70 years old who underwent LPD were assigned to group I, patients ≥ 70 years old who underwent LPD were assigned to group II, and patients ≥ 70 years old who underwent OPD were assigned to group III. Thus, 64 patients were excluded for did not match the rule of the three groups (The OPD patients who are younger than 70). First, group I and group II were compared to explore whether the prognosis of LPD in elderly patients was the same as that in non-elderly patients. Then, we compared group II and group III to explore the advantages and disadvantages of LPD and OPD in elderly patients. Based on the above two analyses, the conclusion is drawn as to whether LPD is suitable for elderly patients. The choice of laparoscopy or traditional open approach was made by the patients or by a random clinical trail from a multicenter study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for inclusion in the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were appropriate for all cases we include, whether it was an open surgery or a laparoscopic surgery.

Inclusion criteria (1) Patients undergoing LPD or OPD surgery for ampullary tumor, pancreatic head tumor, lower common bile duct tumor and descending duodenal tumor. (2) The preoperative imaging assessment without distant metastases, portal vein invasion is less than 180°.

Exclusion criteria (1) Patients who are physically unable to tolerate the effect of pneumoperitoneum pressure or unable to establish pneumoperitoneum. (2) Patients with severe systemic comorbidities. (3) Patients with combined resection of other abdominal organs.

According to the above criteria, three patients were excluded for combined laparoscopic partial transverse colectomy. Then, 64 patients were excluded for did not matching the rule of the three groups (The OPD patients who are younger than 70). Finally, a total of 168 patients were included in the study.

Surgical procedures

All LPD were performed in a total laparoscopic procedure. Patients were placed in the supine position with legs apart, the surgeon was on the right side of the patient, the assistant was on the left side of the patient, the people holding the laparoscope were standing between the legs of the patient, with routine tracheal intubation and general anesthesia, the pneumoperitoneum pressure was 12 mmHg. The artificial pneumoperitoneum was established 1 cm above the umbilicus, and 12-mm trocar was inserted. After laparoscopic exploration of the abdominal cavity, and the peritoneal and visceral surface metastases were excluded, 5- and 10-mm trocar were inserted, respectively, at the right upper axillary front and the middle line of the right clavicle; 5- and 10-mm trocars were inserted, respectively, at the left upper axillary front and the middle line of the left clavicle under the observation of laparoscope. (1) Separation: The gastric collateral ligament was opened below the gastroepiploic artery arch with the ultrasonic dissector, and the right artery of the gastroepiploic was transected. At the upper border of the pancreas, the gastroduodenal artery was isolated and transected, the common hepatic artery and right gastric artery were identified and isolated, and the hepatic artery and common bile duct were isolated along the portal vein, corresponding lymph nodes were cleaned, and the hepatic pedicle was suspended. A tunnel was established between the pancreatic neck and the SMV or portal vein (PV). (2) Dissection of the tissue: the gastric, gallbladder and pancreas were successively dissected, the Kocher incision was opened, the duodenum was dissociated, the jejunum was transected, the uncinate process was dissected, and finally, the Common hepatic duct was dissected, and the specimen was taken out. (3) Reconstruction: the anastomotic of the pancreatic intestine, biliary intestine and gastrointestinal tract were successively reconstructed, mesangial hiatus was closed, and abdominal drainage tube was placed. All OPD surgeries were performed in a traditional manner with Child’s anastomosis procedure. Besides, in all the cases, we performed duct-to-mucosa technique no matter it was LPD or OPD, and we also performed classical Whipple’s resection rather than employing pylorus-preserving technique.

Observational index

(1) General condition: age, gender (male, female), body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (ASA score), initial symptom, hypertension and diabetes mellitus; (2) Operation-related indicators: operation time, blood loss, presence or absence of vascular reconstruction, intraoperative blood transfusion, (3) Postoperative recovery indicators: time to oral intake, all drainage tube removal time, classification of pancreatic fistula (referring to ISGPF standard in 2016 [7]), complications such as delayed gastric emptying, postoperative bleeding, Clavien–Dindo classification, secondary surgery, postoperative time of hospitalization; (4) Oncology related indicators: tumor pathological type, tumor size, lymph node status, R0 resection.

Statistical treatment

SPSS 20.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and those with a non-normal distribution were reported as median with interquartile rage (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as number and proportion. Statistical methods include Student’s t test, Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic characteristics of all patients

The entire cohort consisted of 168 patients operated by the same surgeon. In the first analysis, the baseline characteristics and perioperative outcomes were compared across all LPD patients in groups of 56 elderly patients and 84 non-elderly patients. In the second analysis, the same data were compared between 56 elderly patients who underwent LPD and 28 elderly patients who underwent OPD. Among all the patients (100 men and 68 women), the mean age was 67.9 ± 9.5 years (35–88 years). The mean BMI was 22.8 ± 2.9 (range from 13.2 to 32.4). One hundred and twenty-two (72.6%) and 46 (27.4%) patients were classified as ASA II and III, respectively. Sixty-five (38.7%) patients had hypertension and 32 (19.0%) patients had diabetes. Jaundice and Epigastric pain were the most common initial symptoms, accounting for 36.9% (62 cases) and 45.2% (76 cases), respectively. Of these patients, 15 had both symptoms.

LPD subgroup: elderly versus non-elderly patients

The baseline characteristics and pathological outcomes of group I and group II are shown in Table 1. Comparing elderly to not-elderly LPD patients, there were similar results in gender and ASA score. However, elderly LPD patients had a smaller BMI (22.2 ± 2.9 kg/m2 versus 23.3 ± 2.7 kg/m2, p = 0.022) and a higher hospitalization expenses (12,447.3 (10,189.7–15,340.0) euros versus 11,069.3 (9505.7–13,359.2) euros, p = 0.026) than no-elderly patients. There was no difference between the two groups in terms of pathologic diagnosis, harvest lymph nodes and the proportion of R0 resection cases. The tumor size of elderly group was higher than the other (2.5 (1.9–4.3) cm versus 2.2 (1.7–3.0) cm, p = 0.068). The short-term surgical outcomes are shown in Table 2. There was no difference between elderly and not-elderly LPD patients in terms of operative time, conversion rate, all drainage tube removal time, time of postoperative stay, and proportion of vascular reconstruction, reoperation, pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, Hemorrhage, Clavien–Dindo classification, 30-day readmission and. 90-day mortality. However, the elderly LPD patients had a higher blood loss (380.0 (306.3–447.5) ml versus 370.0 (310.0–420.0) ml, p = 0.003), longer time to oral intake (5.0 (4.0–7.0) day versus 5.0 (3.0–6.0), p = 0.036), and higher proportion of intraoperative transfusion (17.9% versus 6.0%, p = 0.026).

Elderly subgroup: OPD versus LPD

The baseline characteristics and pathological outcomes of group II and group III are shown in Table 1. There was no difference between elderly OPD patients and elderly LPD patients in terms of age, gender, BMI, ASA score, pathological outcomes, tumor size, harvest lymph nodes and the proportion of R0 resection cases. However, hospitalization costs are higher for older patients who choose LPD (12,447.3 (10,189.7–15,340.0) euros vs. 7251.9 (8994.0–11,717.4) euros, p < 0.001). The short-term surgical outcomes are shown in Table 2. Elderly patients who choose LPD had longer operative time (380.0 (306.3–447.5) min versus 292.5 (255.0–342.5) min, p < 0.001), but shorter time to oral intake (5.0 (4.0–7.0) day versus 7.0 (5.0–11.3) day, p = 0.005). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of blood loss, drainage tube removal time and 30-day readmission. Elderly patients who choose LPD performed better in postoperative stay and proportion of intraoperative transfusion, vascular reconstruction, reoperation, pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, Hemorrhage, Clavien–Dindo classification and. 90-day mortality, but not statistically significant.

Discussions

Although some reports showed OPD can be performed safely in selected elderly people [8,9,10], it is too early to say for sure [2, 3]. LPD may be more suitable for the elderly due to its advantages of reduced postoperative pain, less intraoperative blood loss, low incidence of postoperative complications, shorter hospitalization stays and a longer progression-free survival compared with OPD [5, 11,12,13]. but whether elderly patients will also benefit from this minimally invasive approach is still controversial. Laparoscopic approach is like a double-edged sword for the elderly: on the one hand, it can reduce postoperative pain and improve postoperative recovery; on the other hand, the relatively long time of operation and the effect of pneumoperitoneum pressure may be harmful to the elderly. The purpose of this study was to present data and results from a mature surgical team and to put forward our views.

The main conclusions of the relevant data in this study are as follows: first, LPD does not perform as well in elderly as it does in non-elderly patients (with more intraoperative blood loss, higher proportion of intraoperative transfusion and longer time to oral intake), but the overall surgical outcomes were almost the same; then, in elderly patients, when compared with OPD, LPD has the advantage of shorter time to start oral intake but the disadvantage of longer operative time. Due to our data, in elderly patients, LPD always performed better in short-term surgical outcomes, but not statistically significant. On the basis of the above two points, we conclude that LPD is safe for the elderly.

However, LPD had a higher hospitalization cost than OPD in elderly patients. The result contradicted two studies from the United States, which estimated total hospital costs for LPD and OPD at the same level [14, 15]. A group of West China Hospital compared the costs of LPD with OPD during the initial learning curve and found that the higher cost of the LPD group may be due to the higher cost of the surgery and anesthesia [16]. Considering the higher cost of surgical equipment and supplies in China, this may also be the reason for the high cost of our LPD group. However, in the LPD subgroup, the cost of hospitalization in the elderly was significantly higher than that in the non-elderly, which was consistent with Yuan’s findings [3]. This may be related to more complex disease and poorer physical condition in the elderly, which lead to more complications that tend to be more severe [3].

Many studies have shown that LPD may lead to earlier discharge from the hospital compared to OPD [11, 13, 17, 18], even in elderly patients [19]. In this study, though LPD had a shorter mean postoperative stay, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Compared with OPD, LPD is always associated with less intraoperative bleeding [11, 13, 20], even in elderly patients [19, 21], but this study did not reach such a significant difference.

It is worth mentioning that LPD surgery should also take into account the number of LPD surgeries performed each year. A study of 1768 patients aged ≥ 75 years who underwent LPD or OPD in the National Cancer Database (NCDB) from 2010 to 2013 pointed out that the 30-day and 90-day mortality rates of the center where more than 10 LPDs are performed each year are significantly lower than the center where less than 10 LPDs are achieved per year [22]; while, the other two studies pointed out that the annual surgical amount of minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy (MIPD) or LPD should be no less than 22 cases or 25 cases [23, 24].

Our study has several significant limitations. Since it is a retrospective study, there is a selection bias. As our sample size is relatively small, a larger sample size and multi-center study need to be carried out to confirm our findings. Secondly, we lack long-term follow-up data, which is also common in two similar articles [19, 21]. Although Chapman et al. [22] found that LPD had a longer median survival time in older people than OPD, 66.5% of the data were from institutions performing 1–4 cases per year, and these centers would definitely select cases that are healthier, more physically fit, have fewer comorbidities, and less advanced cancers when carrying out LPD, which resulted in selection bias. Last, as an evaluation of a specific surgical technique in elderly patients, it is important to pay attention to cognitive aspects, recovery of autonomy, quality of life and other related issues. Since this is a retrospective study, no relevant data were collected when we performed these surgeries, we couldn’t study the issues. The newly defined perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PND) [25], which include cognitive decline diagnosed before operation; postoperative delirium, delayed neurocognitive recovery, and postoperative neurocognitive disorder, are associated with increased lengths of hospital stay, costs, morbidity, mortality and overall decreased quality of life [26, 27]. Although there have been several reports of better quality of life [28] and lower incidence rate of postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) [29] in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery as compared to open surgery, whether laparoscopic surgery has these advantages is still controversial [30, 31], and we hope that relevant prospective studies can be conducted in the future to make up for this deficiency.

In conclusion, compared with non-elderly patients, LPD resulted in more intraoperative blood loss, more proportion of intraoperative transfusion, and longer time to oral intake in elderly patients. However, in elderly patients, when compared with OPD, LPD performed satisfactory, and the only thing we need to be concerned about LPD is the advantage of shorter time to start oral intake and the disadvantage of longer operative time and a higher hospitalization cost. On the whole, LPD is safe and feasible for elderly people, but we need to consider its high cost and long operative time over OPD.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

He X, Song M, Qu J et al (2019) Basic and translational aging research in China: present and future. Protein Cell 10(7):476–484

Sukharamwala P, Thoens J, Szuchmacher M et al (2012) Advanced age is a risk factor for post-operative complications and mortality after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. HPB 14(10):649–657

Yuan F, Essaji Y, Belley-Cote EP et al (2018) Postoperative complications in elderly patients following pancreaticoduodenectomy lead to increased postoperative mortality and costs. A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 60:204–209

Chen YT, Ma FH, Wang CF et al (2018) Elderly patients had more severe postoperative complications after pancreatic resection: a retrospective analysis of 727 patients. World J Gastroenterol 24(7):844–851

Chen K, Liu XL, Pan Y et al (2018) Expanding laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy to pancreatic-head and periampullary malignancy: major findings based on systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 18(1):102

Zhou J, Xin C, Xia T et al (2017) Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in A-92-older Chinese patient for cancer of head of the pancreas: a case report. Medicine 96(3):e5962

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C et al (2017) The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 161(3):584–591

Lu L, Zhang X, Tang G et al (2018) Pancreaticoduodenectomy is justified in a subset of elderly patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a population-based retrospective cohort study of 4,283 patients. Int J Surg 53:262–268

Shamali A, De’Ath HD, Jaber B et al (2017) Elderly patients have similar short term outcomes and five-year survival compared to younger patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Int J Surg 45:138–143

Ito Y, Kenmochi T, Irino T et al (2011) The impact of surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients. World J Surg Oncol 9:102

Croome KP, Farnell MB, Que FG et al (2014) Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: oncologic advantages over open approaches? Ann Surg 260(4):633–638 (discussion 638-640)

de Rooij T, Lu MZ, Steen MW et al (2016) Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative cohort and registry studies. Ann Surg 264(2):257–267

Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC et al (2017) Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg 104(11):1443–1450

Mesleh MG, Stauffer JA, Bowers SP et al (2013) Cost analysis of open and laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single institution comparison. Surg Endosc 27(12):4518–4523

Gerber MH, Delitto D, Crippen CJ et al (2017) Analysis of the cost effectiveness of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 21(9):1404–1410

Tan CL, Zhang H, Peng B et al (2015) Outcome and costs of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy during the initial learning curve vs laparotomy. World J Gastroenterol 21(17):5311–5319

Poves I, Burdio F, Morato O et al (2018) Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 268(5):731–739

Torphy RJ, Friedman C, Halpern A et al (2019) Comparing short-term and oncologic outcomes of minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy across low and high volume centers. Ann Surg 270(6):1147–1155

Liang Y, Zhao L, Jiang C et al (2019) Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06982-w

Lee CS, Kim EY, You YK et al (2018) Perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign and borderline malignant periampullary disease compared to open pancreaticoduodenectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg

Tee MC, Croome KP, Shubert CR et al (2015) Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy does not completely mitigate increased perioperative risks in elderly patients. HPB 17(10):909–918

Chapman BC, Gajdos C, Hosokawa P et al (2018) Comparison of laparoscopic to open pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc 32(5):2239–2248

Adam MA, Thomas S, Youngwirth L et al (2017) Defining a hospital volume threshold for minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy in the United States. JAMA Surg 152(4):336–342

Kutlu OC, Lee JE, Katz MH et al (2018) Open pancreaticoduodenectomy case volume predicts outcome of laparoscopic approach: a population-based analysis. Ann Surg 267(3):552–560

Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS et al (2018) Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery-2018. Br J Anaesth 121(5):1005–1012

Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF et al (2010) Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 304(4):443–451

Steinmetz J, Christensen KB, Lund T et al (2009) Long-term consequences of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Anesthesiology 110(3):548–555

Hirpara DH, Azin A, Mulcahy V et al (2019) The impact of surgical modality on self-reported body image, quality of life and survivorship after anterior resection for colorectal cancer—a mixed methods study. Can J Surg 62(4):235–242

Gong GL, Liu B, Wu JX et al (2018) Postoperative cognitive dysfunction induced by different surgical methods and its risk factors. Am Surg 84(9):1531–1537

Shin YH, Kim DK, Jeong HJ (2015) Impact of surgical approach on postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing gastrectomy: laparoscopic versus open approaches. Korean J Anesthesiol 68(4):379–385

Tan CB, Ng J, Jeganathan R et al (2015) Cognitive changes after surgery in the elderly: does minimally invasive surgery influence the incidence of postoperative cognitive changes compared to open colon surgery? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 39(3–4):125–131

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This manuscript has not been published nor submitted for publication elsewhere. All authors have contributed significantly, and agree with the content of the manuscript. The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Changzhou First People’s Hospital ethics committee, and has been performed according to the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

The study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standard of the instituional and/or national research committe, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, Y., Tang, T., Zhang, Y. et al. Laparoscopic vs. open pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comparative study in elderly people. Updates Surg 72, 701–707 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00737-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00737-2