Abstract

Tubers of forty four indigenous potato varieties were assessed for storage behaviour at room temperature, tuber dry matter content and cooking quality during 2010, 2011 and 2012. The maximum, minimum temperatures and relative humidity during storage period ranged between 26 to 40 °C, 17–28 °C and 18 to 82 %, respectively. The lowest total weight loss was recorded in variety Kufri Pushkar (7.7 %) followed by Kufri Lalima (7.9 %), Kufri Surya (8.3 %), Kufri Red (9.2 %), Kufri Dewa, Kufri Sheetman (9.3 %), Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Jyoti (9.5 %), Kufri Sindhuri (9.6 %), Kufri Kuber (9.7 %), Kufri Chipsona-1 (9.8 %), Kufri Kundan (9.9 %) and Kufri Chamatkar (10.0 %). Highest tuber dry matter content (%) was observed in Variety Kufri Kundan (24.2) followed by Kufri Himsona (23.7), Kufri Frysona (23.6), Kufri Kuber (22.7), Kufri Chipsona-2 (22.3). Kufri Khasigaro (22.0), Kufri Sheetman (21.9), Kufri Chipsona-3 (21.7) and lowest in Variety Kufri Khyati and Kufri Pukhraj (16.1 %). Of the total varieties, 14 were adjudged as floury, 15 mealy, 14 waxy and one (Kufri Ashoka) as soggy. The total weight loss had highly significant and positive correlation with sprout weight/Kg tubers (r = 0.76**), physiological weight loss (r = 0.97**). Based on the results potato varieties namely, Kufri Chamatkar, Kufri Chipsona-1, Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Dewa, Kufri Jyoti, Kufri Kuber, Kufri Kundan, Kufri Lalima, Kufri Lauvkar, Kufri Pushkar, Kufri Red, Kufri Safed, Kufri Sheetman, Kufri Sindhuri possessed excellent keeping quality with medium to long tuber dormancy, low storage losses, medium to high tuber dry matter and good flavour. The information generated in this study can be utilized in the breeding programme. This can also help the farmer to choose and cultivate the potato varieties as per demand of the consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Potato (Solanuim tuberosum L) is one of the important food crops after wheat rice and maize. It is cultivated worldwide under various climatic conditions. India ranks third in terms of potato area after China and Russia and second in terms of potato production after China in the world during 2011. Potatoes can be consumed in many ways, including baking, boiling, roasting, frying, steaming, and microwaving. Potato is integral part of food and traditional cousins and likely to find more importance in the dietary habit of Indian people. To cater the demand of different agro climatic regions Central Potato Research Institute, Shimla has released 50 potato varieties for cultivation since 1958. Potato is a semi-perishable crop but can be stored for over 6 months at 3–4 °C in cold store. Storage is necessary for a regular supply of potatoes to the consumers during offseason. In India 90 % of the potatoes are grown in sub-tropical plains during winter crop season. The harvesting of potato crop generally coincides with rising temperatures which force the farmers/producers to take immediate decision whether to dispose it off in the table/processing market or to keep it in cold stores. However, many of the small and marginal farmers cannot afford to store as they need cash to meet their production expenses or don’t have access to cold store in their surroundings. Under such circumstances, farmers resort to distress sale. Traditional storage system could be an answer to this but for this knowledge of storage behavior of different varieties which can withstand ambient temperatures at least for 60–75 days is very important enabling the farmers to sale their produce periodically. Previous studies on keeping quality (Kang and Gopal 1993; Singh et al. 2001; Patel et al. 2002; Pande and Luthra 2003; Das et al. 2004; Kumar et al. 2005) conducted under ambient conditions or under non refrigerated storage like heaps, pits and evaporative cooled potato stores (Kumar et al. 1995; Mehta and Kaul 1997 and Mehta et al. 2006) were limited to a few varieties or hybrids. Pande et al. (2007), conducted an extensive study on sprouting behaviour and weight loss of 37 Indian potato varieties under controlled conditions, but, consolidated information on storage behavior of indigenous potato varieties under ambient conditions is lacking.

Beside storage behviour, texture is one of the most important quality attributes of potato tubers. It not only affects consumer preference, but it also influences the release of volatile flavor components during chewing (Lucas et al. 2002). Solid or dry matter is highly correlated with texture. A mealy potato is dry and granular, while a waxy potato is moist and gummy. That means some varieties after cooking, are glistening in appearances feel more or less dry and granular on the tongue. These are characterized as mealy. On the other hand, varieties have a translucent appearance when cooked and feel wet and pasty on the tongue. These are characterized as soggy and waxy (Frederick and Bettelheim 1955). Flavor consists of taste (due to nonvolatile compounds), aroma (due to volatile compounds) and texture (mouth feel). All three components interact to produce a flavour response. Flavour is strongly influenced not only by potato clone, but also by production and storage environments (Jansky 2010). Therefore, in the present study both storage behviour and culinary attributes of Indian potato varieties were evaluated.

Materials and methods

Material and crop management

The experimental material consisted of 44 indigenous potato varieties of different maturity group like, early maturing (7), medium maturing (28) and late maturing (9) released during 1958 to 2009. Seed tubers of these varieties were planted during 20–27 October, in all the three years of study at Central Potato Research Institute Campus, Modipuram, Meerut, UP, India (222 m above mean sea level; 290 N, 760 E). Recommended crop management practices were followed to grow the crop. Haulms were cut 90 days after planting. The crop was harvested 15–20 days after haulm cutting to allow the tubers to attain skin firmness. Subsequently, tubers were kept in heap under shade for 15–20 days for proper curing of tuber skin. These skin cured tubers were utilized for studying the storage behavior and culinary attributes.

Storage behaviour

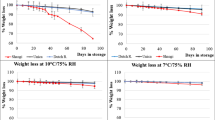

Five Kg clean and uniform size tubers of each variety were packed individually in Hessian cloth bags. This formed one replication. Three such replications were kept at room temperature during first week of March during all the years of experimentation. The number of tubers in each bag was recorded at the beginning of experiment. The bags containing tuber material were stored for 75 days allowing sufficient space of air movement between bags at ambient room temperatures. The maximum and minimum temperatures and relative humidity were recorded every day (Fig. 1 and 2). Percent sprouting of tubers (as calculated from tubers having one or more sprouts above 2 mm long) and number and weight of healthy and rotted tubers were recorded at 45, 60 and at 75 days of storage. The data on Sprout Weight (g) / Kg tuber, % Rottage (number) and % Rottage (weight) were transformed into square roots (√x +0.5) and analyzed as per the statistical methods proposed by Gomez and Gomez (1984).

Tuber dry matter content (TDMC)

Samples of five randomly drawn tubers of each variety were used for dry matter estimation. The tubers were cut horizontically and half part was chopped into small pieces. The chopped pieces were mixed properly and 50 g sample of each variety in 3 replications were kept in oven at 800 C for 72 h (Luthra et al. 2003). The final dry content of the sample was estimated when the weight of the sample reached to a constant level.

Cooking quality

Internal colour, texture and flavour of microwave baked tubers were carried out during 2011–12 after one month of harvesting with panel consisting of four persons. The micro wave baked (for 10–15 min) tubers after cooling were examined. Precaution was taken to wash the mouth before testing the sample (Meitei and Barooah 1980) and the final decision about each organoleptic characteristic was taken on consensus. The texture was adjudged in four major categories i.e. 1) extremely mealy–floury, 2) medium to slightly mealy/granular-Mealy, 3) gummy/pasty−waxy and 4) watery or translucent−soggy. Similarly, flavor (a combination of feel of taste, texture and aroma) of the baked potatoes was examined in four categories i.e. 1) Excellent, 2) Very Good, 3) Good and 4) Average.

Results and discussion

The maximum and minimum temperatures ranged between 26–40 °C to 17–28 °C during the period of storage (Fig. 1 and 2). Relative humidity on the other hand ranged from 43–82 % (morning) and 18–53 % (evening). The results on different storage parameters and cooking quality of potato varieties are described below.

Sprouting beahviour and dormancy period

Large variations were recorded with respect to sprouting behavior and dormancy period. The results on sprouting behaviour (Table 1) revealed that varieties namely, Kufri Dewa and Kufri Lalima did not sprout till 45 days of storage whereas, Kufri Swarna showed short tuber dormancy (83.7 % sprouting). Cultivars Kufri Kumar (76.3 %), Kufri Lauvkar (68.0 %), Kufri Khasigaro (61.0 %), Kufri Bahar (54.5 %) showed relatively higher sprouting but their sprouting level remined below the critical level (80 %) of dormancy. At 60 days of storage sprouting in 15 varieties remained below 80 % with no sprouting in Kufri Lalima followed by Kufri Jyoti (10.0 %), Kufri Red (10.7 %), Kufri Sindhuri (18.5 %), Kufri Safed (20.7 %), Kufri Dewa (26.7 %) and Kufri Pushkar (45.6 %). Whereas, Kufri Arun, Kufri Bahar, Kufri Chipsona-3, Kufri Frysona, Kufri Giriraj, Kufri Jawahar, Kufri Kumar, Kufri Kundan, Kufri Lauvkar, Kufri Naveen, Kufri Pukhraj and Kufri Swarna attained 100 % sprouting at 60 days storage. At 75 days only six varieties showed sprouting less than 80 %. Sprouting in Kufri Lalima was lowest (2.1 %) followed by Kufri Jyoti (24.9 %), Kufri Sindhuri (35.1 %), Kufri Dewa (51 %), Kufri Pushkar (59.2 %) and Kufri Red (60.4 %). The study did not show apparent differences in days to sprout between different maturity class (i.e. early, medium and late). As late maturing variety Kufri Kumar, medium maturing variety Kufri Swarna took 45 days to reach 75–80 % sprouting. No relation between maturity class and days to 80 % sprouting was found as reported by earlier workers (Burton 1989, Roztropowicz and Wardzynska 1974).

Dormancy is considered to be the varietal character that might gets influenced by the soil and environmental conditions during crop growth and storage environment (Ezekiel and Singh 2003). Among various factors temperature is considered to be most important physical factors affecting dormancy and it is reported that within the range of 3–200 C, tubers stored at lower temperature have a longer period of innate dormancy than those stored at higher temperatures (Wiltshire and Cobb 1996).

Physiological weight loss and weight loss due to sprouts

Reduction in weight of tubers due to evaporative losses from the tuber surface (skin) is considered as physiological weight loss. Excessive evaporative losses not only reduce weight but also cause shrinkage on the tuber skin and consequently affect the market value of tubers. Physiological weight loss in test varieties ranged from 7.5 % (Kufri Lalima, Kufri Pushkar) to 17.5 % (Kufri Jeevan) up to 75 days of storages. As many as 10 varieties namely, Kufri Lalima, Kufri Pushkar, Kufri Sindhuri, Kufri Surya, Kufri Dewa, Kufri Jyoti, Kufri Sheetman, Kufri Red, Kufri Kundan, Kufri Chandramukhi exhibited lower mean physiological weight loss (<9 %). However, the magnitudes of losses were higher during 2009–10 as compared to 2010–11 and 2011–12. This could be attributed to high temperatures (minimum and maximum) and relative humidity especially up to 5th week of storage period. It is generally believed that varieties with longer dormancy period may perform better under non-refrigerated storage conditions. It has been reported that sprouted potatoes loose much more weight than un-sprouted potatoes (Van Es and Hartmans 1987). Among the varieties tested, percent weight loss due to sprouts was in higher range in varieties, Kufri Swarna (13 g /Kg tuber at 75 days of storage) followed by Kufri Kumar (9.5 g) and Kufri Jeevan (9.4 g) which might have contributed to high physiological weight loss in these varieties (Table 2). Ezekiel et al. (2004) based on studies in un-sprouted tubers of 11 varieties reported that weight loss in potato varieties during storage is related with the periderm thickness, number of cell layers in the periderm and also with the number of lenticels on the tuber surface. They found Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Chipsona-1 and Kufri Sindhuri as superior over a period of 120 days as the weight loss was under acceptable limit compared to other varieties under study. They observed relatively higher weight loss in varieties Kufri Chipsona-2, Kufri Anand and Kufri Badshah.

Tuber rottage

Rottage makes the tuber unfit for consumption and also induces the infection in the adjacent tubers kept for storage. The mean percent rottage by weight, in most of the varieties remained below 1.0 %, however, three varieties of medium maturity group viz., Kufri Arun (3.9 %), Kufri Sherpa (3.7 %), Kufri Giriraj (3.5 %); one early variety Kufri Khyati (3.0 %) and two late varieties viz., Kufri Jeevan (2.2 %), Kufri Naveeen (1.8 %) exhibited relatively higher rottage as compared to other varieties. Significantly higher rottage during first year (2009–10) of experiment was recorded in most of the varieties (Table 3). The variable response of different genotypes, prevailing temperature and humidity might have attributed to variable rottage percentage during different year of experiment. Raghav and Singh (2003) in an experiment involving 12 potato varieties under room temperature, found maximum rottage in Kufri Jawahar followed by Kufri safed. However, Mehta et al. (2006) reported highest rottage in Kufri Arun at 105 days of storage.

Total weight loss

Total weight loss in potato varieties determines the longevity of their storage and also their keeping quality. Total weight loss (including evaporative and respiratory weight loss of tubers & sprouts and weight loss due to rottage) at 75 days of storage showed large variation between varieties and year in the study (Table 4). Mean total weight loss was recorded lowest in variety Kufri Pushkar (7.7 %) followed by Kufri Lalima (7.9 %), Kufri Surya (8.3 %), Kufri Red (9.2 %), Kufri Dewa, Kufri Sheetman (9.3 %), Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Jyoti (9.5 %), Kufri Sindhuri (9.6 %), Kufri Kuber (9.7 %), Kufri Chipsona-1 (9.8 %), Kufri Kundan (9.9 %), Chamatkar (10.0 %). Whereas, varieties viz., Kufri Jeevan (20.6 %) followed by Kufri Swarna and Kufri Sherpa (17.0 %) exhibited higher mean total weight loss in comparison to other varieties under study. Total weight loss, like rottage and physiological weight loss was also significantly high during first year of experiment due to higher temperature and relative humidity. A number of studies (Singh et al. 2001, Patel et al. 2002, Bhutani and Khurana 2005, Mehta et al. 2006 and Kang et al. 2007) related to Indian potato varieties are in accordance with the present findings. The keeping quality of Indian potato varieties based on total weight loss observed in this study, can be grouped as excellent (<10 % total weight loss), very good (10–12 %), good (12–15 %), average (15–20 %) and poor keeper (>20 % weight loss). Based on the results the 13 varieties namely, Kufri Pushkar, Kufri Lalima, Kufri Surya, Kufri Red, Kufri Dewa, Kufri Sheetman, Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Jyoti, Kufri Sindhuri, Kufri Kuber, Kufri Chipsona-1, Kufri Kundan and Kufri Chamatkar were found to be excellent keeper (<10 % total weight loss). Varieties viz., Kufri Badshah, Kufri Anand, Kufri Sutlej, Kufri Safed, Kufri Ashoka, Kufri Girdhari, Kufri Himalini, Kufri Jawahar, Kufri Lauvkar, Kufri Muthu, Kufri Pukhraj, Kufri Frysona, Kufri Kanchan, Kufri Neela, Kufri Chipsona-3 and Kufri Bahar found to be very good keeper (10–12 % total weight loss). However, 10 varieties viz., Kufri Alankar, Kufri Shailja, Kufri Himsona, Kufri Khasigaro, Kufri Megha, Kufri Chipsona-2, Kufri Khyati, Kufri Sadabahar, Kufri Naveen, Kufri Arun and Kufri Giriraj were found to be good keeper (12–15 % total weight loss). Three varieties namely, Kufri Kumar, Kufri Sherpa and Kufri Swarna were average keeper (15–20 % total weight loss) and one variety Kufri Jeevan was poor in keeping quality (>20 % total weight loss). The potato varieties with minimum total weight loss retains the tuber firmness and fetches good market prices for longer period of time. Such varieties could also be promoted for long distance transportation and export purpose as well.

Tuber dry matter content

Tuber dry matter is important parameter for considering the suitability of potatoes for different purposes. It ranges from 16.1 % to 24.2 % in Indian varieties at 90 days of harvest (Table 4). The highest percent tuber dry matter (Table 5) was observed in Variety Kufri Kundan (24.2 %) followed by Kufri Himsona (23.7 %), Kufri Frysona (23.6 %), Kufri Kuber (22.7 %), Kufri Chipsona-2 (22.3 %), Kufri Khasigaro (22. 0 %), Kufri Sheetman (21.9 %) and Kufri Chipsona-3 (21.7 %). Potato varieties like Kufri Chiposna-1. Kufri Chiposna-2, Kufri Chipsona-3, Kufri Himsona and Kufri Frysona possess comparatively high dry matter and are suitable for processing purposes (chips, French fries and flakes) to meet demand of growing processing industry. Potato varieties with relatively low-moderate in dry matter content namely, Kufri Khyati, Kufri Pukhraj (16.1 %) followed by Kufri Anand (17.3 %), Kufri Giriraj (17.4 %) and Kufri Pushkar (17.4 %) are suitable for table purposes.

Cooking quality

Out of 44 varieties, 14 were adjudged as floury, 15 as mealy, 14 as waxy and one (Kufri Ashoka) as soggy (Table 5). Similarly, 28 of them had cream, 7 light yellow and 9 white flesh colour after peeling. All the 14 floury varieties possessed moderately high mean dry matter content (20.9 %) with a range of 18.1 % (Kufri Badshah) to 23.7 % (Kufri Himsona). Jansky (2008), Leung et al. (1983), van Dijk et al. (2002) and Mosley and Chase (1993) also observed association of mealiness with high tuber dry matter content. Average tuber dry matter content of mealy textured varieties was 18.84 % and ranged from 16.1 (Kufri Khyati) to 22.7 % (Kufri Kuber). However, average tuber dry matter content of waxy varieties was slightly higher than mealy (19.59 %) varieties. It indicated that dry matter content did not always associate with the mealiness. As in the present study variety Kufri Jawahar with 18.6 % tuber dry matter categorized as mealy and other variety Kufri Jyoti with same percentage of tuber dry matter content was adjudge as waxy. These findings are in confirmation with results of Brittin and Trevino (1980), True and Work (1981) and Unrau and Nylund (1957). Besides dry matter, texture is also influenced by cultivars having varying cell wall density and the degree of solubilization of the middle lamella and cell walls. (van Marle et al. 1997). In general floury texture is preferred for processing purposes whereas waxy texture is liked for boiling and canning. The varieties with soggy texture are suitable for pan frying, salads, boiling and canning (Mosley and Chase, 1993).

Potato flavour

On the basis of consensus of panel tasters, four varieties were adjudged as excellent, 13 very good, 24 good and three of them were found to have average flavour. Potato varieties namely, Kufri Chipsona-1, Kufri Khasigaro, Kufri Neela and Kufri Sherpa possessed excellent flavor. Among these, the flavour of the Kufri Chipsona-1 is one of reason for its popularity as table potato apart from its wide use in processing purpose. Potato varieties namely, Kufri Badshah, Kufri Bahar, Kufri Chamatkar, Kufri Chipsona-2, Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Dewa, Kufri Frysona, Kufri Himsona, Kufri Kumar, Kufri Kundan, Kufri Pushkar, Kufri Red and Kufri Safed possessed very good flavour (Table 5). The reason for varying flavours includes plant genotype, production & storage environment and the enzymes that react with them to produce flavour compounds (Jansky 2010).

Correlation between different attributes of potato storage parameters

The weight loss increased with sprout growth. This is primarily due to the fact that sprout growth adds to the surface area of the tuber and high permeability of sprout wall to water vapour leads to greater water loss. It has been reported that the surface area of sprouts equivalent to 1 % of that of tuber could double the potential rate of evaporation (Singh and Ezekiel 2003). In this study also sprouting percentage at 75 days of storage had highly significant positive correlation with percent physiological weight loss (r = 0.52**, n = 42), sprout weight g/Kg tuber (r = 0.31**, n = 42) and percent total weight loss (r = 0.45**, n = 42) (Table 6). Percent rottage by weight had positive and significant correlation with physiological weight loss (r = 0.51**), total weight loss (r = 0.70**), sprout weight g/Kg tuber (r = 0.27**), and negatively correlated with percent tuber dry matter (r = −0.21). Pande and Luthra (2003) also reported that genotypes with high physiological weight loss and rottage resulted in high total weight loss leading to deterioration of keeping quality.

Correlation coefficients (n = 42) between tuber dry matter and texture (r = 0.33*) and tuber dry matter and flavour (r = 0.32*) were significant and positive which indicated that potato varieties with high tuber dry matter possess floury texture which endorsed the findings of Mosley and Chase (1993). Although starch is tasteless, it influences texture and can interact with flavouring compounds during cooking (Jitsuyama et al. 2009; Solms and Wyler 1979). The correlation between texture and flavour was low (0.10).

Conclusions

Besides high yield, the storage and cooking quality of potatoes are the most important features which insure high returns to the producer but at the same time it provides security to the traders and consumers for deriving assured benefits/satisfaction. A number of varieties (old and new) have traditionally been popular for various uses in different parts of India. Based on these results potato varieties namely, Kufri Chamatkar, Kufri Chipsona-1, Kufri Chandramukhi, Kufri Dewa, Kufri Jyoti, Kufri Kuber, Kufri Kundan, Kufri Lalima, Kufri Lauvkar, Kufri Pushkar, Kufri Red, Kufri Safed, Kufri Sheetman, Kufri Sindhuri possessed excellent keeping quality with medium to long tuber dormancy, low storage losses, medium to high tuber dry matter and good flavour.

References

Bhutani RD, Khurana SC (2005) Storage behaviour of potato genotypes under ambient conditions. Potato J 32(3/4):209–210

Brittin HC, Trevino JE (1980) Acceptability of microwave and conventionally baked potatoes. J Food Sci 45:1425–1427

Burton WG (1989) Post harvest physiology. The Potato, third edn, Longman Scientific and Technical, Essex, pp 423–522

Das M, Ezekiel R, Pandey SK, Singh AN (2004) Storage behaviour of potato varieties and advanced cultures at room temperature in Bihar. Potato J 31(1/2):71–75

Kumar D, Kaul HN, Singh SV (1995) Keeping quality in advanced potato selections during non-refrigerated storage. J Indian Potato Assoc 22(3/4):105–108

Ezekiel R, Singh B (2003) Seed physiology. In: Khurana SM P, Minhas JS, Pandey SK (eds) The potato production and utilization in sub-tropics. Mehta Publishers, New Delhi, pp 301–313

Ezekiel R, Singh B, Sharma ML, Garg ID, Khurana SM P (2004) Relationship between weight loss and periderm thickness in potatoes stored at different temperatures. Potato J 31:135–140

Frederick A, Bettelheim CS (1955) Factors associated with potato texture i specific gravity and starch content. J Food Sci 20(1):71–79

Gomez KA, Gomez AA (1984) Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. Wiley, New York, 680 p

Jansky SH (2008) Genotypic and environmental contributions to baked potato flavor. Am J of Potato Res 85:455–465

Jansky SH (2010) Potato Flavor. Am J Potato Res 87:209–217

Jitsuyama Y, Tago A, Mizukami C, Iwama K, Ichkawa S (2009) Endogenous components and tissue cell morphological traits of fresh potato tubers affect the flavor of steamed tubers. Am J Potato Res 86:430–441

Kang GS, Gopal J (1993) Differences among potato genotypes in storability at high temperature after different periods of storage. J Indian Potato Assoc 20(2):105–110

Kang GS, Kumar R, Gopal J, Pandey SK, Khurana SMP (2007) Kufri Pushkar - a main crop potato variety with good keeping quality for Indian plains. Potato J 34(3/4):147–152

Kumar R, Pandey SK, Khurana SM P (2005) Keeping quality of potato processing varieties during room temperature storage. Potato J 32(1–2):55–59

Leung HK, Barron FH, Davis DC (1983) Textural and rheological properties of cooked potatoes. J Food Sci 48:1470–1474

Lucas PW, Prinj JF, Agarwal KR, Bruce IC (2002) Food physics and oral physiology. Food Qual Prefer 13:203–213

Luthra SK, Gopal J, Pandey SK (2003) Selection of superior parents and crosses in potato for developing cultivars suitable for early planting in UP. J Indian Potato Assoc 30(1–2):1–2

Mehta A, Kaul HN (1997) Physiological weight loss in potatoes under non-refrigerated storage: contribution of respiration and transpiration. J Indian Potato Assoc 24(3/4):106–113

Mehta A, Singh SV, Pandey SK, Ezekiel R (2006) Storage behaviour of newly released potato cultivars under non-refrigerated storage. Potato J 33(3/4):158–161

Meitei WI, Barooah S (1980) Organoleptic test of potato varieties under agro-climatic conditions of Jorhat (Assam) J. Indian Potato Assoc 7(3):162–164

Mosley AR, Chase, RW (1993) Selecting Varieties and Obtaining Healthy Seed Lots. In: Potato Health Management, APS Press pp. 19–27

Pande PC, Luthra SK (2003) Performance and storability of advanced potato hybrids in west central plains. J Indian Potato Assoc 30:21–22

Pande PC, Singh SV, Pandey SK, Singh B (2007) Dormancy sprouting behaviour and weight loss in Indian potato (Solanum tuberosum) varieties. I J Agr Sci 77(11):715–720

Patel RN, Kanbi VH, Patel CK, Patel NH, Chaudhari SM (2002) Room temperature storage of some advanced potato hybrids and varieties in the plains of Gujarat. J Indian Potato Assoc 29(3/4):159–161

Raghav M, Singh NP (2003) Differences among potato cultivars for their storability under room temperature. Progress Hortic 35(2):196–198

Roztropowicz S, Wardzynska H (1974) Observation of tuber dormancy in twenty Polish potato varieties. Biul Inst Ziem 14:147–164

Singh B, Ezekiel R (2003) Influence of relative humidity on weight loss in potato tubers stored at high temperatures. Indian J Plant Physiology 8:141–144

Singh SV, Pandey SK, Khurana SMP (2001) Storage behaviour of some advanced potato hybrids in plains of Western UP at ambient temperatures. J Indian Potato Assoc 28(1):135–136

Solms J, Wyler R (1979) Taste components of potatoes. In: Boudreau JC (ed) Food taste chemistry. American Chemical Society, Washington, pp 175–184

True RH, Work TM (1981) Sensory quality of Ontario potatoes compared with principal varieties grown in Maine. Am Potato J 58:375–379

Wiltshire JJJ, Cobb AH (1996) A review of the physiology of potato tuber dormancy. Ann Ap Biol 129:553–569

van Dijk C, Fischer M, Holm J, Beekhuizen JG, Stolle-Smits T, Boeriu C (2002) Texture of cooked potatoes (Solanum tuberosum). 1. Relationships between dry matter content, sensory-perceived texture, and near-infrared spectroscopy. J Agr Food Chem 50:5082–5088

van Marle JT, Stolle-Smits T, Donkers J, van Dijk C, Voragen AGJ, Recourt K (1997) Chemical and microscopic characterization of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cell walls during cooking. J Agr Food Chem 45:50–58

van Es A, Hartmans KJ (1987) Dormancy, sprouting and sprout inhibition. In: Storage of potatoes Rastovski A and van Es A et al. (Eds). Pudoc, Wageningen, the Netherlands pp 114–32

Unrau AM, Nylund RE (1957) The relation of physical properties and chemical composition to mealiness in the potato. I Physical properties Am J Potato Res 34(9):245–253

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the taste panelists who contributed to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, V.K., Luthra, S.K. & Singh, B.P. Storage behaviour and cooking quality of Indian potato varieties. J Food Sci Technol 52, 4863–4873 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-014-1608-z

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-014-1608-z