Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the 1- and 3-year overall survival rates. This prospective observational study was conducted at a tertiary care center in Bihar state, India. The study analyzed 228 patients in Bihar with a median age at diagnosis of 55 ± 12.05 years. The most common symptoms included upper abdominal pain (26.3%), weight loss (14%), and ascites (13.6%). The majority of patients presented at stage IV (72.8%), with liver metastasis being prevalent (61.4%). Interventional biliary drainage was performed in 9.6% of cases, and systemic chemotherapy was received by 84.64%, while 15.36% opted for best supportive care. Univariate Cox regression analysis identified Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, stage, gallstone disease, and surgical intervention as significant risk factors influencing overall survival (OS) (p < 0.001). Multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed ECOG performance status (p < 0.001), stage (p = 0.039), and surgical intervention (p = 0.038) as independent factors impacting OS. One-year OS rates for stages II, III, and IV were 100%, 97%, and 44%, respectively, while 3-year OS rates were 29%, 4%, and 0%. Surgical intervention significantly influenced OS (p < 0.001). OS for surgical intervention was 28 months, and for inoperable cases, it was 12 months. One- and 3-year OS for surgical intervention were 95% and 11%, while for inoperable cases, they were 41% and 0%, respectively. Patients with gallbladder cancer, particularly in Bihar’s Gangetic plains, face poor survival, especially with advanced disease. Adequate surgery improves outcomes, prompting a call for enhanced strategies, particularly for locally advanced GBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) has a marked variation of incidence around the globe. It is an aggressive and highly lethal neoplasm of the biliary tract [1]. GBC constitutes the most common biliary tract malignancy and the 7th most common among gastrointestinal neoplasms and accounts for 80–95% of the biliary tract cancer [2, 3]. The incidence of GBC is notably higher among the Indian population when compared to global statistics as a whole. In terms of GBC, the population in North and Northeast India exhibits a notably higher incidence rate compared to Chile and Bolivia [4, 5]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, GBC accounts for 84,695 deaths in 2020 and 115,949 new cases globally [6]. GBC accounts for 14,736 deaths and 19,570 new cases in 2020 in India [7]. The regions near the river Ganges in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh and western Bihar are identified as the highest-risk areas for GBC [8]. One possible explanation for this disparity could be the significant impact of environmental factors on the development of GBC etiology in these regions [9]. Carcinogens such as heavy metals and azo dyes are known to enhance the risk of cancer in this region, possibly due to mutation in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [10, 11]. The clinical presentation is often nonspecific resulting in a significant delay in diagnosis. Most of the time, GBC is detected incidentally at the time of cholecystectomy or due to symptoms advanced disease such as jaundice, ascites, or obstruction [12]. The management of GBC continues to pose challenges due to the vague and nonspecific nature of its signs, symptoms, and the delay in diagnosis. Surgery remains the sole potential cure for GBC, but its effectiveness is limited to patients diagnosed in the early stages of the disease. Patients with advanced-stage GBC often cannot undergo radical resection due to the frequent metastasis of tumors to nearby organs [13]. The objective of this study is to assess the prognostic factors influencing survival and examine the survival outcomes of patients with GBC residing in state of Bihar, India.

Methods

This prospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Radiotherapy at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Patna, Bihar. The study spanned a period of 3 years, from January 2017 to December 2019. The workup and diagnosis of the GBC included history and clinical examination of the patients, ultrasonography (USG) of whole abdomen, contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) whole abdomen, CT scan thorax, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CEMRI) abdomen when needed. USG/CT-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed on the gallbladder lesion/mass. Patients with obstructive jaundice underwent percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) stenting if possible. Workup of hematological and biochemical parameters included complete blood count (CBC), liver function test (LFT), kidney function test (KFT), prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and CA19.9. Following multidisciplinary tumor board discussion, operable cases underwent extended cholecystectomy and postoperative cases were advised for adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients were staged according to AJCC TNM (American Joint Committee on Cancer) staging system 8th edition [14]. Incidental diagnosis of GBC following open cholecystectomy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients was considered for extended cholecystectomy with port site excision if operable and followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Advanced GBC or patients with poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status were considered for best supportive care.

Objective: to find out the 1-and 3-year overall survival (OS) and factors influencing it.

Inclusion criteria: age > 18 years of age, histopathologically or cytopathologically confirmed cases of GBC. Exclusion criteria: age < 18 years, pregnancy or lactation, residence outside of Bihar, diagnosed with concurrent second primary.

Variables: demographic data, clinicopathological information of GBC, management of GBC, follow-up (survival status). Outcome variable included the overall survival (the length of time from the diagnosis of GBC until the death due to progression of the GBC). Progression of GBC included the evidence of progressive disease (radiological or biochemical) after the intended completion of treatment.

Data analysis: data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (IBM® SPSS® Inc., Chicago, USA). Descriptive statistics were employed to describe the patient demographics. Cox regression model was utilized for univariate analysis of OS; variables having statistically significant influence on OS were included in Cox regression model for multivariate analysis to identify independent factors affecting OS. The Kaplan–Meier method was employed to determine the cumulative survival rate, and group comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

Result

Clinicopathological Characteristics

Two hundred and twenty-eight patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were analyzed. The median age at diagnosis was 55 ± 12.05 years, with a majority falling within the 50–60-year age group (30.70%). The female-to-male ratio was 2.86:1, with females constituting 74.1% of the total patients. Geographical distribution of GBC patients in Bihar state is depicted in heat map (Fig. 1).

The most common presenting symptom was upper abdominal pain (26.3%), followed by weight loss (14%) and ascites (13.6%). Thirty-seven point three percent (37.3%) of patients presented with an ECOG performance status of 2. Gallbladder stones were noted in 57% of patients at presentation, and surgical intervention was feasible in only 27.6% of cases. Histopathologically, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma were observed in 95.6%, 3.5%, and 0.9% of cases, respectively. Most patients presented at stage IV (72.8%). Immunohistochemistry confirmed that all two (0.9%) patients with undifferentiated carcinoma had neuroendocrine tumors. In these two patients, there was no evidence of metastasis to other site. Both of these patients have undergone PET CT scan at staging workup to exclude primary site other than the gallbladder. The liver (61.4%) was the most common site of metastasis, followed by omental deposits (3.1%) at the presentation of metastatic gallbladder cancer. Table 1 illustrates the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with gallbladder carcinoma.

Interventional biliary drainage, either in the form of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (6.1%) or stenting at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (3.5%), was performed in 9.6% of patients (details given in Table 2). The median value of CA 19.9 was 366.60, with its distribution among patients categorized as < 200, 200–400, > 400–600, and > 600 showing percentages of 9.6%, 48.7%, 25.9%, and 15.8%, respectively. Systemic chemotherapy, either with adjuvant intent or palliative intent, was received by 84.64% of patients, while 15.36% were considered for best supportive care. 27.2% of the patients were considered for adjuvant chemotherapy and 57.5% of the patients were considered for palliative chemotherapy and the rest of 15.4% patients were considered for best supportive care. None of the patients received adjuvant radiotherapy. During data analysis, 221 (96.9%) patients showed disease progression, and among those with progressive disease, 206 patients died.

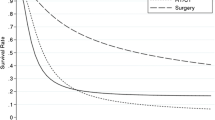

Clinical Characteristics and Survival

The overall median survival was 14 months (95% CI 12.518–15.482), as depicted in Fig. 2. One- and 3-year OS rates were 57% and 3%, respectively. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that the survival rates of the patients with different categorical variables progressively decrease with the increase in the duration of follow-up in months. The result of log-rank test showed a statistically significant difference (log-rank test; χ2 = 132.45; p = < 0.001) in OS when comparing the stage of the GBC. The median OS in stage II, stage III, and stage IV was 30 months (95% CI of 26.501–33.499), 26 months (95% CI of 23.255–28.745), and 12 months (95% CI of 11.473–12.527) shown in Fig. 3. One-year OS in stage II, stage III, and stage IV was 100%, 97%, and 44%, respectively, while the 3-year OS in stage II, stage III, and stage IV was 29%, 4%, and 0%. A statistically significant difference (log-rank test; χ2 = 128.87; p < 0.001) in OS was observed when comparing the surgical interventions (radical cholecystectomy and cholecystectomy), as depicted in Fig. 4. The OS in patients who underwent surgical intervention was 28 months (95% CI of 25.195–30.805), while the OS in patients with inoperable gallbladder carcinoma was 12 months (95% CI of 11.473–12.527). The 1- and 3-year OS for patients who underwent surgical intervention were 95% and 11%, respectively, whereas the 1- and 3-year OS for patients with inoperable gallbladder carcinoma were 41% and 0%, respectively. No difference in OS was observed when comparing the values of CA19.9 among groups at the time of diagnosis.

Risk Factors and Overall Survival

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to analyze the hazard ratio (HR). The results of Cox regression univariate analysis indicated that ECOG performance status (p < 0.001), stage (p < 0.001), gallstone disease (p < 0.001), and surgical intervention (p < 0.001) at diagnosis were the risk factors influencing the OS in gallbladder carcinoma. Age group (p = 0.168), gender (p = 0.921), histopathological subtypes (p = 0.855), and CA19.9 group (p = 0.061) did not influence the OS in gallbladder carcinoma.

The multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that ECOG performance status (p < 0.001), stage (p = 0.039), and surgical intervention (p = 0.038) were the independent factors influencing the OS in gallbladder carcinoma. The univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses are depicted in Table 3.

Discussion

Gallbladder carcinoma is the predominant malignancy in the biliary tract system, with the highest incidence observed in northern and central India. In developing nations, it commonly presents in advanced stages, significantly diminishing the chances of successful curative resection [15,16,17,18].

The median age at presentation was 67 years in a Memorial Sloan–Kettering report of 435 GBC patients [19]. In our study, the median age is 55 years, suggesting that the incidence of GBC increases with age. These findings align with previous studies conducted in India [18, 20, 21].

GBC exhibits a higher incidence in females globally, ranging from 2 to 6 times more than in males. This trend is particularly notable in the northern part of India, Pakistan, and among American-Indian females. In our study, the female-to-male ratio is 3.53:1 [22, 23]. A previous study from New Delhi reported GBC incidence as 1/100,000 in males and 3.3/100,000 in females during 1987–1996, with a female-to-male ratio of 3.3:1 [20, 24]. Our study similarly highlights GBC as predominantly affecting females, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.8:1. This observation aligns with other studies reporting a female-to-male ratio of 2.5–3:1 [21, 25].

Upper abdominal pain emerged as the most common presenting symptom in our study. The clinical signs mimic those of benign gallbladder disease until the invasion of surrounding structures provides a clue leading to an accurate diagnosis [26]. Similar observations were reported by other studies [27,28,29]. In our study, adenocarcinoma (95.6%) was the most common histology, followed by squamous cell carcinoma (3.5%). Lal et al. reported 89.15% adenocarcinoma and 2.4% squamous cell carcinoma in their study. Hamdani et al. and Beltz et al., in their studies, also reported a similar distribution of histopathological types of GBC [27, 30].

In this study, the majority of patients presented in stage IV (72.8%), with the liver (61.4%) being the most common site of metastasis. Dubey et al., in their study, reported almost similar findings, with 72.06% of patients in stage IV and 57.14% having metastasis to the liver [31]. Batra et al. reported in their study that about 76% of GBC patients presented with stage IV [12]. Similarly, Gupta et al. reported findings consistent with our study, where 71.4% of patients presented in stage IV [32].

In our study, the median value of CA 19.9 was 366.60 U/mL, with 48.7% of patients having CA19.9 levels within the range of 200–400. Sinha SR et al. reported a median value of CA 19.9 of 112.9 U/mL in their study [33], while Zhijian et al. reported a median value of CA 19.9 of 278 U/mL [34]. Elevated CA19.9 levels in patients with GBC without jaundice have been associated with metastatic disease, showing high specificity and potential for prognostication. CA19.9 was found to be superior to CEA in predicting tumor burden and recurrence [35].

In our study, 15.36% of patients were considered for best supportive care due to their poor ECOG performance status. Singh et al. reported a similar finding in their study, with 18.6% of patients considered for best supportive care due to poor performance status [36].

Gallstones have been reported to be present in 61–90% of patients with gallbladder cancer [37]. However, the incidence of GBC in a population with gallstones varies from 0.3 to 3% only. In our study, 57% of patients had evidence of gallstones, aligning with the existing literature.

Our study demonstrated that surgical intervention was associated with improved OS. Surgery remains the sole treatment modality offering a survival benefit in cases of GBC. Over the past decade, various studies have shown a significant increase in 5-year survival rates, rising from 5 to 12% and even up to 38%. In contrast, palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy has shown limited effectiveness for GBC, providing only a few months of survival benefit, if any. Given this situation, an aggressive surgical approach for locally confined disease is entirely justified. There is a lack of consensus worldwide on what constitutes aggressive surgery for a given stage of GBC [36]. Surgeons must exercise heightened caution when overseeing patients who have fortuitously discovered gallbladder cancers subsequent to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. During laparoscopic removal of the gallbladder, it is essential to use a protective bag to prevent the potential dissemination and implantation of tumor cells. Surgeons should consistently document instances of gallbladder wall breach and whether the specimen was enclosed within a bag before extraction during the cholecystectomy procedure [15, 17, 38, 39].

In this study, the OS was 14 months, with 1- and 3-year OS rates of 53% and 3%, respectively. Patients who underwent surgical intervention experienced significantly improved OS compared to those who were unable to undergo surgical intervention. The 1-year OS rates in stage II, stage III, and stage IV were 100%, 97%, and 44%, respectively. The 3-year OS rates in stage II, stage III, and stage IV were 29%, 4%, and 0%. A study by Singh et al. reported 1-year survival rates of 100%, 76%, and 36.6% in stage II, III, and IV, respectively [36], and similar findings were observed in the study by Principe et al. [40].

Conclusion

The survival of GBC patients is very poor, especially for those diagnosed with advanced disease. The geographical region of the patients, namely, the Gangetic plains of Bihar, is one of the areas with a high incidence of GBC. Patients with gallstone disease should be considered at high risk for developing GBC, especially in the context of this geographical area and the age group at risk. It is essential to provide adequate workup and surgical intervention for these high-risk group patients. While adequate surgical intervention is associated with improved OS, there is room for improvement in the treatment strategies for locally advanced GBC. More focused efforts are needed to enhance the outcomes for patients facing locally advanced GBC.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Feroz Z, Gautam P, Tiwari S et al (2022) Survival analysis and prognostic factors of the carcinoma of gallbladder. World J Surg Onc 20:403. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-022-02857-y

Donohue JH, Stewart AK, Menck HR (1998) The national cancer data base report on carcinoma of the gall bladder, 1989–1995. Cancer 83:2618–2628

Hundal R, Shaffer EA (2014) Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol 6:99–109

Schmidt MA, Marcano-Bonilla L, Roberts LR (2019) Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and genetic risk associations. Chin Clin Oncol 8:31

Dutta U, Bush N, Kalsi D, Popli P, Kapoor VK (2019) Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer in India. Chin Clin Oncol 8:33

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A et al (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71:209–249

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/356-india-fact-sheets.pdf (assessed on 19/6/2023)

Dixit R, Shukla VK (2014) Why is gallbladder cancer common in the gangetic belt? In: R. Sudhakaran P (eds) Perspectives in Cancer Prevention-Translational Cancer Research. Springer, New Delhi. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-1533-2_12

Pérez-Moreno P, Riquelme I, García P, Brebi P, Roa JC (2022) Environmental and lifestyle risk factors in the carcinogenesis of gallbladder cancer. J Pers Med 12:234

Dwivedi S, Mishra S, Tripathi RD (2018) Ganga water pollution: a potential health threat to inhabitants of Ganga basin. Environ Int 117:327–338

Soliman AS, Lo AC, Banerjee M, El-Ghawalby N, Khaled HM, Bayoumi S et al (2007) Diferences in K-ras and p53 gene mutations among pancreatic adenocarcinomas associated with regional environmental pollution. Carcinogenesis 28:1794–1799

Batra Y, Pal S, Dutta U et al (2005) Gallbladder cancer in India: a dismal picture. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:309–314

Miller G, Jarnagin WR (2008) Gallbladder carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 34(3):306–312

Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL et al (eds) (2017) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edn. Springer, New York

Mishra S, Chaturvedi A, Mishra NC (2003) Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Lancet Oncol 4:167–176

Sharma A, Dwary AD, Mohanti BK (2010) Best supportive care compared with chemotherapy for unresectable gallbladder: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Oncol 28:4581–4586

Zhu AX, Hong TS, Hazel AF (2010) Current management of gallbladder carcinoma. The Oncol 15:168–181

Kapoor VK, McMichael AJ (2003) Gallbladder cancer: an ‘Indian’ disease. The Nat Med Jour India 16:209–213

Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil D, Jarnagin W, Fong Y et al (2008) Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC). J Surg Oncol 98:485–489

Shukla VK, Khandelwal C, Roy SK (1985) Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder: a review of a 16 year period at the University hospital. J Surg Oncol 28:32–35

Pandey M, Pathak AK, Gautam A (2001) Carcinoma of the gallbladder: a retrospective review of 99 cases. Digest Dis and Sci 46:1145–1151

Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2006) Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer 118:1591–1602

Konstantinidis IT, Deshpande V, Genevay M, Berger D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Tanabe KK et al (2009) Trends in presentation and survival for gallbladder cancer during a period of more than 4 decades: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg 144:441–447

Rai A, Mohanpatra SC, Shukla HS (2004) A review of association of dietary factors in gallbladder cancer. Indian J Cancer 41:147–151

Nandakumar A, Gupta PC, Gangadharan P, Visweswara RN, Parkin DM (2005) Geographic pathology revisited: development of an atlas of cancer in India. Int J Cancer 116:740–754. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.21109

Piehler JM, Crichlow RW (1978) Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder. Surg Gynecol Obstet 147:929–942

Hamdani NH, Qadri SK, Aggarwalla R (2012) Clinicopathological study of gall bladder carcinoma with special reference to gallstones: our 8-year experience from Eastern India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13:5613–5617

Khan RA, Wahab S, Maheshwari V, Khan MA, Siddiqui S et al (2010) Advanced presentation of gallbladder cancer: epidemioclinicopathological study to evaluate the risk factors and assess the outcome. J Pak Med Assoc 60:217–219

Lal M, Raheja S, Bhowmik KT (2018) Carcinoma gallbladder-epidemiological trends in a tertiary hospital in North India. Arch Surg Oncol 4:131. https://doi.org/10.4172/2471-2671.1000131

Beltz WR, Condon RE (1974) Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder. Ann Surg 180:180–184

Dubey AP, Rawat K, Pathi N, Viswanath S, Rathore A, Kapoor R, Pathak A (2018) Carcinoma of gall bladder: demographic and clinicopathological profile in Indian patients. Oncol J India 2(1):3–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/oji.oji_1_18

Gupta A, Gupta S, Siddeek RAT, Chennatt JJ, Singla T, Rajput D, Kumar N, Sehrawat A, Kishore S, Gupta M (2021) Demographic and clinicopathological profile of gall bladder cancer patients: study from a tertiary care center of the sub-Himalayan region in Indo-Gangetic Belt. J Carcinog 9(20):6. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcar.JCar_3_21

Sinha SR, Prakash P, Singh RK, Sinha DK (2022) Assessment of tumor markers CA 19–9, CEA, CA 125, and CA 242 for the early diagnosis and prognosis prediction of gallbladder cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 14(11):1272–1284

Wen Z, Si A, Yang J, Yang P, Xinwei Yang Hu, Liu XY, Li W, Zhang B (2017) Elevation of CA19-9 and CEA is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with resectable gallbladder carcinoma. HPB 19(11):951–956

Sachan A, Saluja SS, Nekarakanti PK, Nimisha, Mahajan B, Nag HH, Mishra PK (2020) Raised CA19–9 and CEA have prognostic relevance in gallbladder carcinoma. BMC Cancer 20(1):826. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07334-x

Singh SK, Talwar R, Kannan N et al (2018) Patterns of presentation, treatment, and survival rates of gallbladder cancer: a prospective study at a tertiary care centre. J Gastrointest Cancer 49(3):268–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-017-9940-y

Reid KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Donohue JH (2007) Diagnosis and surgical management of gallbladder cancer: a review. J Gastrointest Surg. 11:671–81

Giuliante F, Ardito F, Vellone M (2006) Port-sites excision for gallbladder cancer incidentally found after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 191:114–116

Steinert R, Nestler G, Sagynaliev E (2006) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and gallbladder cancer. J Surg Oncol 93:682–689

Principe A, Del Gaudio M, Ercoloni G, Golfieri R, Cucchetti A, Pinna AD (2006) Radical surgery for gallbladder carcinoma: possibilities of survival. Hepatogastroenterology 53(71):660–664

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Dr Dharmendra Singh, Dr Pritanjali Singh, Dr Avik Mandal, and Dr Amrita Rakesh. The first draft of the manuscript along with figures was prepared by Dr Dharmendra Singh, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna (IEC/2018/315 dated 04/10/2018).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, D., Singh, P., Mandal, A. et al. Prognostic Insights and Survival Analysis of Gallbladder Cancer in Bihar, India: a Prospective Observational Study Emphasizing the Impact of Surgical Intervention on Overall Survival. Indian J Surg Oncol 15 (Suppl 2), 196–203 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-024-01925-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-024-01925-x