Abstract

The objective is to study the clinico-demographic profile, treatment patterns and oncological outcomes in borderline mucinous tumours of the ovary. Retrospective cohort analysis was carried out between January 2017 and December 2019 for patients with a diagnosis of borderline mucinous tumours of the ovary who were treated at our centre. Kaplan–Meier method was used for the estimation of the probability of DFS and OS. Univariate and multivariate analyses based on the Cox proportional hazard model were performed to identify factors associated with DFS and OS. A p-value ≤ 0.05 in a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant. The study population included 75 patients and the median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 24 months. The 5-year DFS for the entire cohort was 79.6% and OS was 90.5%, whereas for stage I disease, 5-year OS was 92.6% as opposed to 60% in the advanced stage. On univariate analysis, only the stage of the disease had a significant association with DFS and OS. Fertility-preserving surgeries had no impact on OS or DFS, and hence, it is suggested that fertility-sparing surgeries may be considered a viable option in young patients with mucinous ovarian tumours. Borderline mucinous tumours of the ovary have excellent survival outcomes and fertility-sparing surgeries should be done whenever feasible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mucinous tumours of the ovary (MOT) are a rare histologic type, accounting for 3–5% of cases of all epithelial ovarian tumours [1]. Borderline mucinous tumours account for 15% of ovarian mucinous tumours, and among them, the intestinal type and endocervical type are the two main histological subtypes [2]. Clinical presentation, biological tumour markers, histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) are fairly distinct from the other epithelial ovarian tumours [3]. There is a considerable overlap in behaviour and clinical presentation among borderline mucinous ovarian tumours and mucinous tumours of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract especially low-grade variants, thereby causing difficulty in diagnosis and their management [4, 5]. There is a paucity of data in literature with regard to accurate clinical and oncological behaviour of borderline mucinous ovarian tumours. In this study, we aimed to study the clinico-demographic profile, treatment patterns and oncological outcomes in borderline mucinous tumours of the ovary.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective cohort analysis of all patients with a diagnosis of borderline mucinous tumours of the ovary who were treated at our tertiary cancer care centre between January 2017 and December 2019. Patients with a diagnosis of benign mucinous tumours or invasive mucinous tumours were excluded. All information was retrieved from electronic medical records after the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board (IEC No: 3828/2021). Clinico-demographical data, treatment details, survival outcomes and follow-up data were gathered. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (the statistical package for social sciences) version 25.0 IBM Corp. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time interval between the date of surgery and the date of recurrence or death due to any cause or the date of last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval between the date of surgery to the date of death due to any cause or the date of last follow-up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for the estimation of DFS and OS. Univariate and multivariate analyses based on the cox proportional hazard model were performed to identify factors associated with DFS and OS. A p-value ≤ 0.05 in a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study population included 75 patients treated primarily with surgery between January 2017 and December 2019 (Table 1). The median age at presentation was 39.3 years and 70.6% of cases were in premenopausal and perimenopausal age groups. The majority of patients presented with abdominal distension (93% of cases) and had disease confined to one ovary presenting as an enlarged adnexal mass in 79% of cases and with ascites in only 7% of cases. In patients presenting with abdominal lumps, only one patient had a fixed mass on clinical examination along with radiological findings of hydroureteronephrosis. Only four patients (5.3%) were diagnosed incidentally. Tumour markers were not elevated in the majority of our patients with median values for CA125 being 25.9 (range 5–125,925), CEA 2 (range 0.5–527) and CA19.9 15 (range 1–9820).

Out of 75 patients, 71 patients (95.9%) underwent surgical staging, and three were taken up for interval debulking surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) (Table 2). One patient was not operated upon as she was in stage III at presentation and had a very poor performance status. Among the patients with stage I who underwent surgery, five had tumour spillage or intraoperative tumour rupture. Peritoneal washings were negative in two and one patient had atypical cells. None of these received adjuvant chemotherapy, and two of them had a recurrence in the opposite ovary for which they underwent repeat surgery. A total of 36 patients (48%) out of 75 had fertility-sparing surgery in the form of either unilateral adnexectomy or cystectomy. Hysterectomy was omitted in those undergoing conservative surgery with unilateral adnexectomy. In 48% of the patients, the uterus was not removed which corresponds with the patients undergoing unilateral adnexectomy. Lymph node dissection was not commonly performed in our series and only two patients underwent lymphadenectomy; nodes were uninvolved in both of them.

Appendicectomy was initially considered a part of staging surgery for mucinous tumours, 8.1% of these, i.e., 6 patients, underwent appendicectomy in a grossly normal-looking appendix intraoperatively and no evidence of malignancy subsequently on histopathology. One patient required resection and anastomosis of the transverse colon in a primary setting with optimal surgery. A total of 72 patients (97.3%) had optimal cytoreduction. Among the two suboptimally operated cases, one patient received adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) and the other was kept on observation. Both of them recurred in the form of peritoneal disease; one patient who was initially kept on observation was subsequently planned for secondary cytoreduction while the other who received adjuvant CT was advised palliative care and treatment.

A total of 9 patients were given chemotherapy during primary treatment in adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting. Five patients were given in adjuvant setting after primary surgery and 4 in neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings. All stage III–operated patients received chemotherapy, one in adjuvant, and three in neoadjuvant and adjuvant basis. Four patients with stage IC disease received adjuvant chemotherapy in view of positive cytology. Out of these 9 patients who received CT, 4 cases recurred and 3 of them were stage III disease.

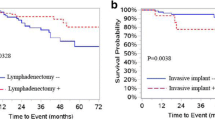

A total of 11 recurrences (14.9%) were noted in the study population (Table 3). Seven of these recurrences were in patients with stage I disease. The 5-year RFS for the entire cohort was 79.6% and OS was 90.5%, whereas for stage I disease, the 5-year OS was 92.6% as opposed to 60% in the advanced stage (Table 3; Figs. 1 and 2) On univariate analysis, only the stage of disease was significantly associated with increased recurrence rate and worse OS (Table 4).

Discussion

Characteristically mucinous tumours are more commonly seen in young females and are one of the predominant neoplasms of the reproductive age group [6, 7]. SEER cancer registry analysis showed that 26% of mucinous tumours occurred in women less than 40 years [8]. Their serous counterparts also are more common in the younger age group, mean age being 45 years [9]. In this age group, primary invasive mucinous tumours of the ovary are less common and need to be distinguished from metastatic mucinous tumours of the pancreas, colon, breast and gall bladder [10].

Primary mucinous tumours are clinically characterised by unilateral large masses occupying the entire abdomen, smooth surface and absence of extraovarian disease like ascites and peritoneal deposits [10]. Bilateral disease, ovarian surface involvement and/or size < 10 cm usually favour metastatic ovarian involvement [11]. Around 83% of primary ovarian MOT is present in stage I [12]. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas are rarely of primary ovarian origin, and such cases deserve thorough metastatic workup to rule out primary tumours from the colorectal, breast, endocervix or pancreatico-biliary tract [13].

Tumour markers are a part of the routine workup for ovarian masses. CA125, CEA and CA19.9 are routinely done for suspected epithelial ovarian cancers. Levels of CA125 are usually elevated in the serous subtype while CEA and CA19.9 are raised in the mucinous subtype [14]. CEA is more specific for mucinous histology and is frequently raised in mucinous rather than non-mucinous histology (88% v/s 19%) [15, 16]. In our study, 4 cases out of 6 of stage II/III had raised CEA, as opposed to 5 out of 69 cases of stage I tumours. The study by Tamakoshi et al. and Cho et al. suggested that CA125 has a higher association with mucinous tumour workup followed by CA19.9 and CEA [16]. Endoscopic evaluation of the upper GI and lower GI tract is mandatory during workup for mucinous tumours when they present as advanced malignancies or bilateral tumours so as to differentiate primary from metastatic tumours of the ovary [17, 18]. In our study, 15 patients underwent endoscopic evaluation either due to raised CEA/CA19.9 values or imaging suggestive of advanced disease or IHC markers in favour of GI primary. Nine patients underwent preoperative cytology and 4 had preoperative biopsy in our study; all these patients had imaging suggestive of metastatic disease with ascites and peritoneal deposits. The majority of patients who had ovary-confined disease on CT/MRI was taken up for primary surgery.

Surgery has always been a cornerstone in the treatment of ovarian cancer. It is done either as a staging laparotomy for early disease or as a cytoreductive procedure in advanced stage III/IV disease. Staging surgery comprises of adnexectomy with or without a frozen section followed by hysterectomy, exploration of the entire abdominal cavity and viscera systematically for evidence of disease, biopsies from suspicious areas, lymphadenectomy and omentectomy. Cytoreductive surgeries usually are ultra-radical surgeries comprising of multi-visceral resections, peritonectomy, upper abdominal surgeries such as diaphragmatic stripping and/or splenectomy. Considering that the majority of patients with borderline MOTs present at an early stage and in younger population, an individualised and tailored approach is needed in surgical management rather than a blanket treatment. Areas which can be considered for modification are fertility-sparing surgery, omission of lymphadenectomy and the need of appendicectomy.

Meta-analysis by Hoogendam et al. studying the role of lymphadenectomy in early stage I and II disease showed that lymph-nodal involvement is as low as 0.8% and 1.2% and concluded that routine lymphadenectomy should be avoided as the risks outweigh the benefits [19]. Another study by Matsou et al. studied 4066 patients with mucinous histology, out of which 2210 underwent lymphadenectomy but did not show any benefit in survival [20]. Mulyderman et al. retrospectively studied lymph node involvement in subtypes of MOTs and confirmed higher lymph node involvement in the infiltrative subtype than expansile. In our study, only 2.7% of the patients underwent lymphadenectomy as a part of surgical staging, and all the nodes were uninvolved [21]. Hence, lymphadenectomy can be safely omitted during staging for mucinous tumours without affecting the survival outcomes.

Traditionally appendicectomy is included as a part of staging for mucinous tumours. Ozcan et al. studied the role of appendicectomy in a retrospective study and concluded that normal-looking appendix should not be removed and appendicectomy should be done only for abnormal-looking appendix [22]. This was also supported by another study by Cheng et al., who recommended careful intraoperative inspection of the appendix and omitting appendicectomy in normal-looking appendix [23]. On the contrary, a Danish study by Rosendahl and colleagues found microscopic involvement of the appendix in grossly normal-looking appendix in 2 out of 179 cases, advocating appendicectomy as a part of staging surgery in mucinous tumours [24]. In our study, 8.1% patients underwent appendicectomy for a normal-looking appendix, and there was no evidence of malignancy on histopathology. Should appendicectomy still be considered a part of staging in mucinous ovarian tumours? We advocate the omission of appendicectomy in a normal-looking appendix during staging for borderline MOTs.

Mucinous tumours are prevalent in the reproductive age group, and fertility-sparing management is often discussed as most of these tumours present in the early stage. A study by Bentivegna et al. studied the role of fertility-sparing surgery in ovarian cancer and included 280 patients with mucinous ovarian tumours [25]. It showed a recurrence rate of 6.3% and observed that recurrences occurred mainly in the peritoneum than in the preserved/opposite ovary and were often fatal. Guoy et al. studied fertility-sparing surgery in subtypes of MOTs and showed FSS had similar oncological outcomes in expansile as well as infiltrative subtypes [26]. They recommended FSS in stage I tumours but not beyond stage IC. On the contrary, Rodrigeuz et al. limited fertility-sparing options only to the expansile type of MOTs as the infiltrative subtype showed inferior outcomes [27]. In our study, 48% of patients underwent conservative surgery including cystectomy and unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Our study showed that the type of surgery has no significant association with DFS (HR 1.126 CI 0.290–6.077, p = 0.890) and OS (HR 0.357 CI 0.037–3.484, p = 0.376). We strongly suggest fertility-sparing as a viable option in young patients with mucinous tumours.

Studies till now have shown an inferior response to chemotherapy in mucinous tumours. Even though the molecular profile of MOTs is similar to GI tumours, chemotherapy response to GI-based combination CT like capecitabine or 5-FU (5-flurouracil) is not superior to standard CT for ovarian cancers. The GOG 241 study was designed to evaluate whether GI-based or platinum-based regimen was superior in mucinous tumours, but due to poor accrual, the trial was closed prematurely [28]. In our study, we have preferred paclitaxel and carboplatin doublet in neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings. Another retrospective study by Nasioudis et al. analysed 4000 patients with early-stage MOTs and concluded that adjuvant chemotherapy did not show any favourable outcomes in DFS and OS [29]. Platinum resistance looks like an important prognostic factor for advanced-stage MOTs. All patients with advanced stage received chemotherapy in our study, and all of them recurred. In our study, chemotherapy had no significant association with DFS (HR 1.457 CI 0.269–7.892, p = 0.662) and OS (HR 1.498 CI 0.225–9.964, p = 0.6760.376).

Residual disease is one of the most important prognostic factors in borderline MOTs [30]. Out of 75 patients, only two patients had suboptimal resection and they presented as advanced stage III disease at presentation. After suboptimal resection, they received adjuvant chemotherapy, had recurrent peritoneal disease and were declared palliative. Poor response to chemotherapy mainly platinum resistance is also a reason for poor outcomes in advanced and recurrent mucinous ovarian tumours [31]. Our study had five patients in advanced stage III. One of them was declared palliative during the initial workup due to extensive disease burden mainly in the upper abdomen and poor performance status. Two of the five stage III tumours received neoadjuvant CT followed by interval surgery and adjuvant CT, and two underwent primary cytoreductive surgery—one was kept on observation and the other received adjuvant chemotherapy. All of these five patients recurred and three of them were declared palliative; one patient who was kept on observation was planned for secondary cytoreduction but later defaulted.

Stage I borderline mucinous tumours of ovaries have an excellent prognosis with an excellent 5-year OS > 90%. This is at par with stage I borderline serous tumours which have prognosis and 5-year OS as good as 99% [18, 32]. With advanced-stage tumours, 5- and 10-year survival for serous tumours is 95% and 88%, respectively, but advanced stage in borderline mucinous tumours have survival as low as 12–33 months [32]. Our study showed significant difference in both DFS (HR 3.072 CI 1.265–7.458, p = 0.013) and OS (HR 2.661 CI 0.608–11.641; p = 0.194) among early-stage versus advanced-stage tumours. This stark contrast can be attributed to the aggressive biology with peritoneal and visceral involvement along with poor sensitivity to any type of chemotherapy.

Borderline MOTS are usually characterised by the absence of WT1, estrogen and expression of progesterone receptors and PAX8 during IHC. They usually demonstrate diffuse expression of cytokeratin 7 with uneven co-expression of cytokeratin 20 and variable, generally low expression, CDX2 in approximately 40% of cases [33].

This study is limited by its retrospective single-centre study design. The study lacks data on the use of IHC, the role of HIPEC and targeted therapy in mucinous tumours. Future studies emphasising the role of IHC and targeted therapy may be done in collaboration with other centres to reach better conclusions.

Conclusion

Borderline mucinous tumours of the ovary have excellent survival outcomes, and fertility-sparing surgeries should be done whenever feasible. Regular follow-up is essential, and the need to differentiate primary from metastatic tumours of ovary with the help of radiology, pathology and IHC is mandatory.

References

Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Huntsman DG, Santos JL, Swenerton KD, Seidman JD, Gilks CB (2010) Differences in tumor type in low-stage versus high-stage ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 29:203–211

Prat J, D’Angelo E, Espinosa I (2019) Ovarian carcinomas: at least five different diseases with distinct histological features and molecular. Hum Pathol 80:11–27

Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Köbel M et al (2019) Invasive epithelial ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage. J Natl Cancer Inst 111:60–68

McCluggage WG (2012) Immunohistochemistry in the distinction between primary and metastatic ovarian mucinous neoplasms. J Clin Pathol 65:596–600

Kurman RJ, Shih I-M (2016) The dualistic model of ovarian carcinogenesis: revisited, revised, and expanded. Am J Pathol 186:733–747

Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Haiba M, Boice CR, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM (2004) The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol 23:41–44

Yoshikawa N, Kajiyama H, Mizuno M, Shibata K, Kawai M, Nagasaka T, Kikkawa F (2014) Clinicopathologic features of epithelial ovarian carcinoma in younger vs. older patients: analysis in Japanese women. J Gynecol Oncol 25:118–123

Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Köbel M, Harris HR, Berchuck A, Rossing MA, Schildkraut JM, Doherty JA (2019) Invasive epithelial ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage. J Natl Cancer Inst 111:60–68

Carbonnel M, Layoun L, Poulain M, Tourne M, Murtada R, Grynberg M, Feki A, Ayoubi JM (2021) Serous borderline ovarian tumor diagnosis, management and fertility preservation in young women. J Clin Med 10(18):4233

McGuire V, Jesser CA, Whittemore AS (2002) Survival among U.S. women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 84:399–403

Yemelyanova AV, Vang R, Judson K et al (2008) Distinction of primary and metastatic mucinous tumors involving the ovary: analysis of size and laterality data by primary site with reevaluation of an algorithm for tumor classification. Am J Surg Path 32:128–138

Seidman JD, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM (2003) Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas in the ovaries: incidence in routine practice with a new approach to improve intraoperative diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 27:985–993

Zaino RJ, Brady MF, Lele SM et al (2011) Advanced stage mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary is both rare and highly lethal: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 117:554–562

Clement PB, Young RH (2014) Atlas of gynecologic surgical pathology, 3rd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Tuxen MK, Sölétormos G, Dombernowsky P (1995) Tumor markers in the management of patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 21:215–245

Tamakoshi K, Kikkawa F, Shibata K et al (1996) Clinical value of CA125, CA19-9, CEA, CA72-4, and TPA in borderline ovarian tumor. Gynecol Oncol 62:67–72

Cho HY, Kyung MS (2014) Serum CA19-9 as a predictor of malignancy in primary ovarian mucinous tumors: a matched case-control study. Med Sci Monit 20:1334–1339

Morice P, Gouy S, Leary A (2019) Mucinous ovarian carcinoma. N Engl J Med 380:1256–1266

Hoogendam JP, Vlek CA, Witteveen PO, Verheijen RHM, Zweemer RP (2017) Surgical lymph node assessment in mucinous ovarian carcinoma staging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 124:370–378

Matsuo K, Machida H, Mariani A, Mandelbaum RS, Glaser GE, Gostout BS, Roman LD, Wright JD (2018) Adequate pelvic lymphadenectomy and survival of women with early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol 29:1–15

Muyldermans K, Moerman P, Amant F, Leunen K, Neven P, Vergote I (2013) Primary invasive mucinous ovarian carcinoma of the intestinal type: importance of the expansile versus infiltrative type in predicting recurrence and lymph node metastases. Eur J Cancer 49:1600–1608

Ozcan A, Töz E, Turan V, Sahin C, Kopuz A, Ata C, Sancı M (2015) Should we remove the normal-looking appendix during operations for borderline mucinous ovarian neoplasms?: A retrospective study of 129 cases. Int J Surg 18:99–103

Cheng A, Li M, Kanis MJ, Xu Y, Zhang Q, Cui B, Jiang J, Zhang Y, Yang X, Kong B (2017) Is it necessary to perform routine appendectomy for mucinous ovarian neoplasms? A retrospective study and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 144:215–222

Rosendahl M, Haueberg Oester LA, Høgdall CK (2017) The importance of appendectomy in surgery for mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer 27:430–436

Bentivegna E, Fruscio R, Roussin S, Ceppi L, Satoh T, Kajiyama H, Uzan C, Colombo N, Gouy S, Morice P (2015) Long-term follow-up of patients with an isolated ovarian recurrence after conservative treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer: review of the results of an international multicenter study comprising 545 patients. Fertil Steril 104:1319–1324

Gouy S, Saidani M, Maulard A, Bach-Hamba S, Bentivegna E, Leary A, Pautier P, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Genestie C, Morice P (2018) Results of fertility-sparing surgery for expansile and infiltrative mucinous ovarian cancers. Oncologist 23:324–327

Rodríguez IM, Prat J (2002) Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 75 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 26:139–152

Gore ME, Hackshaw A, Brady WE, Penson RT, Zaino RJ, McCluggage WG, Ganesan R, Wilkinson N, Perren T, Montes A et al (2015) Multicentre trial of carboplatin/paclitaxel versus oxaliplatin/capecitabine, each with/without bevacizumab, as first line chemotherapy for patients with mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC). J Clin Oncol 33:5528

Nasioudis D, Haggerty AF, Giuntoli RL, Burger RA, Morgan MA, Ko EM, Latif NA (2019) Adjuvant chemotherapy is not associated with a survival benefit for patients with early stage mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 154:302–307

Kajiyama H, Suzuki S, Utsumi F, Yoshikawa N, Nishino K, Ikeda Y, Niimi K, Yamamoto E, Kawai M, Shibata K et al (2019) Comparison of long-term oncologic outcomes between metastatic ovarian carcinoma originating from gastrointestinal organs and advanced mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 24:950–956

Xu W, Rush J, Rickett K, Coward JIG (2016) Mucinous ovarian cancer: a therapeutic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 102:26–36

Trimble CL, Kosary C, Trimble EL (2002) Long term survival and patterns of care in women with ovarian carcinoma: a population based analysis. Gynecol Oncol 86:34–37

Sahraoui G, Fitouri A, Charfi L, Driss M, Slimane M, Hechiche M, Mrad K, Doghri R (2022) Mucinous borderline ovarian tumors: pathological and prognostic study at Salah Azaiez Institute. Pan Afr Med J 29(41):349

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gynecological Oncology DMG (disease management group) for their constant support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S.S.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization; D.M.: data curation, writing—review and editing, methodology, investigation; A.C.: data curation, writing—review and editing, methodology, investigation; S.G.: methodology, formal analysis; P.P.: data curation, writing—review and editing, methodology, investigation, formal analysis; SM: data curation, writing—review and editing; M.T.: writing—review and editing, supervision. AM: writing—review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shylasree, T.S., Mahajan, D., Chaturvedi, A. et al. Clinicopathological and Oncological Outcomes of Borderline Mucinous Tumours of Ovary: a Large Case Series. Indian J Surg Oncol 15, 88–94 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-023-01849-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-023-01849-y