Abstract

The gold standard surgical management of curable rectal cancer is proctectomy with total mesorectal excision. Adding preoperative radiotherapy improved local control. The promising results of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy raised the hopes for conservative, yet oncologically safe management, probably using local excision technique. This study is a prospective comparative phase III study, where 46 rectal cancer patients were recruited from patients attending Oncology Centre of Mansoura University and Queen Alexandra Hospital Portsmouth University Hospital NHS with a median follow-up 36 months. The two recruited groups were as follows: group (A), 18 patients who underwent conventional radical surgery by TME; and group (B), 28 patients who underwent trans-anal endoscopic local excision. Patients of resectable low rectal cancer (below 10 cms from anal verge) with sphincter saving procedures were included: cT1-T3N0. The median operative time for LE was 120 min versus 300 in TME (p < 0.001), and median blood loss was 20 ml versus 100 ml in LE and TME, respectively (p < 0.001). Median hospital stay was 3.5 days versus 6.5 days (p = 0.009). No statistically significant difference in median DFS (64.2 months for LE versus 63.2 months for TME, p = 0.85) and median OS (72.9 months for LE versus 76.3 months for TME, p = 0.43). No statistically significant difference in LARS scores and QoL was observed between LE and TME (p = 0.798, p = 0.799). LE seems a good alternative to radical rectal resection in carefully selected responders to neoadjuvant therapy after thorough pre-operative evaluation, planning and patient counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The gold standard surgical management of curable rectal cancer is proctectomy with total mesorectal excision. Total mesorectal excision (TME) reduced the 5-year local recurrence rate to less than 10%. Adding preoperative radiotherapy improved local control of resectable rectal cancer. 5-year local control rate using a short course (5 × 5 Gy) pre-operative radiotherapy was 6% compared to 11% after TME surgery alone [1, 2].

Surgical morbidity is variable from anastomotic leakage (9%), early or late complications for 25–50% of patients (including stoma-related complications), and postoperative mortality in up to 2% of patients [3]. Distal cancers are often treated by abdomino-perineal resection (APR) with a permanent colostomy [4].

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) gives the potential of increasing number of patients who can have sphincter preservation, although only few prospective trials have declared this [5, 6]. Moreover, rectal preservation strategies in such patients would be a revolution and may have a significant impact on the quality of life, by avoiding radical surgery and its side effects [7].

A tumour pathological complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant CRT was documented in 8–27% of the patients [8, 9]. Complete “responders” have showed enhancing overall survival and local recurrences with ypT0 and ypT1 (pT0 and pT1 postneoadjuvant) ranging from 0 to 6% [10].

The promising results of neoadjuvant CRT raised the hopes for more conservative, preservative, yet oncologically safe management, probably using local excision technique [9, 11].

Patients and Methods

This study is a prospective comparative non-randomized phase III study, where 46 rectal cancer patients were recruited from patients attending Oncology Centre of Mansoura University and Queen Alexandra Hospital Portsmouth University Hospital NHS with a median follow-up 36 months. The two recruited groups were as follows: group (A), 18 patients who underwent conventional radical surgery by TME; and group (B), 28 patients who underwent trans-anal endoscopic local excision. The selection of surgical option was discussed with each patient after thorough evaluation by the multidisciplinary team. Patients of resectable rectal cancer with sphincter saving procedures were included in the study: distal rectal adenocarcinoma (below 10 cm from the anal verge), received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, T1-T3 tumour with 0–3 lymph nodes ≤ = 8 mm, or non-suspiciously enlarged lymph nodes by radiology on initial staging. We excluded patients planned for abdomino-perineal resection, T4 tumours, metastatic disease, perforated or obstructed tumours, and medically unfit patients for surgery and chemoradiotherapy.

Preoperative Preparation

Pre-neoadjuvant therapy assessment included staging by chest and abdominal CT with contrast and MRI pelvis with contrast. Colonoscopy and biopsy were done to obtain histopathology and exclude synchronous lesions. Neoadjuvant therapy given was either long course chemoradiotherapy course in 27 patients (50 Gy over 5 weeks, 5 days a week) with concomitant capecitabine and oxaliplatin or short-course radiotherapy which was implemented in 19 patients (45 Gy over a week) after 5-flurouracil radio-sensitization. Restaging was done 6–8 weeks after neoadjuvant, by digital rectal examination, whole body CT scan, and MRI pelvis with contrast, in addition to tumour markers (CEA, CA19.9). Patterns of response were then assessed by endoscopic examination, in addition to MRI evaluation of response (mrTRG) in patients who received long course chemoradiation.

Surgical Technique

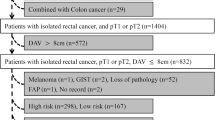

After at least 6 weeks of long-course chemoradiation (LCRT) or the nearest operative list after short-course radiation (SCRT) group, good responders underwent either: radical rectal resection by proctectomy with total mesorectal excision, in which the anal sphincter is preserved, or covering ileostomy. Total mesorectal excision patients were surgically approached either laparoscopically, trans-anal assisted (taTME), robotically, or open. While for trans-anal endoscopic local excision group, the tumour was excised with adequate safety margins using either Karl-Storz trans-anal endoscopic operations (TEO), Richard-Wolff trans-anal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS), or Parks proctoscope. Completion (secondary) TME was done in patients with poor tumour response in LE specimen. The study protocol is summarized in a flow-chart (Fig. 1).

Follow-Up

The postoperative specimen was pathologically evaluated and re-staged (ypTNM) according to AJCC system. The surgical outcomes in terms of intra- and post-operative complications were reported (early and late). The oncological outcomes in terms of recurrence, DFS, and OS were analysed, by the digital rectal examination (plus or minus EUA) every 3 months, follow-up whole-body post-contrast CT every 6 months, and follow-up post-contrast MRI every 6 months. The functional outcomes including the defecatory function by LARS (low anterior resection syndrome) score were obtained either by post or interview or telephone call at least 6 months after finishing adjuvant therapy and/or reversal of stoma. Patient satisfaction, and quality of life (QoL) were assessed by European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QoL-C30 questionnaire, after at least 3 months from reversal of the temporary stoma.

Statistical Analysis

-

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Qualitative data were described using number and percent. Quantitative data were described using median (minimum and maximum) for non-parametric data and mean, standard deviation for parametric data after testing normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the (0.05) level. Qualitative data was analysed using Chi-square or Monte Carlo or Fisher Exact correction as appropriate, while quantitative data was analysed using Student’s t test for parametric tests, and Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric tests. Kaplan–Meier test was used to calculate k χ2.

Results

The mean age for local excision group was younger in TME group (64.5 and 55.5 respectively) but was not statistically significant (p = 0.098). Gender was equally distributed in the local excision group, with male predominance in the TME group. Poorer performance was noted in local excision group which was reflected by the more advanced age in this group, and tendency of patients to avoid morbidity of radical surgery of TME. Neither gender nor ASA were statistically significant between the two study groups (Table 1).

TME group showed more advanced tumours; 6 patients were T2, 12 patients were T3, which was statistically significant (p = 0.019). Maximum tumour diameter at pretherapy was not statistically significant between local excision and TME group (2.1 and 2.9, respectively, p = 0.9). Five patients of local excision group showed an enlarged meso-rectal lymph node but with no suspicious criteria (median size 11 mm), versus four patients in TME group (median size 8.5 mm) (p = 0.905) (Table 1).

Long-course chemoradiation was implemented more in patients of TME (17 out of 18 against 10 out of 28 in local excision group), while short course was administered in 64.3% of patients of local excision and in only one patient of TME group, which showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.001). This is attributed to the more locally advanced tumours of TME group, in addition to variations of MDT decisions between the UK and Egypt.

The difference between the two groups in timing of surgery after neoadjuvant was not statistically significant (median was 12 weeks in LE group versus 10 weeks in TME group, p = 0.22), with three exceptionally long-time intervals in local excision group (20, 22, and 45 weeks) due to logistic issues and long waiting lists (Table 1).

The operative data summarized in Table 1 is consistent with what is expected from such a less invasive surgical approach as LE against radical surgery which involves pelvic dissection, colonic mobilization, re-joining the bowel, and diverting stoma.

R0 resections were accomplished in 16 TMEs (88.9%). In LE group, only four patients had R1 resection. Three of them refused completion surgery and referred for brachytherapy. Secondary TME was done in only three patients, one because of metabolically active meso-rectal lymph node in a postoperative PET scan, which was biopsied using EUS, and another because of persistent bleeding per rectum (with no data of recurrence) (Table 2).

Of the three patients of secondary TME, only one patient showed a pathologically positive node. While only one LE specimen retrieved an adjacent meso-rectal lymph node which was pathologically negative. Postoperative local excision specimen showed complete pathologic response (ypT0) in 6 patients (21.4%), while in TME group, complete pathologic response was shown in specimens of nine patients (50%) (Table 2).

As regards postoperative morbidity, early complications were reported in 4 patients of LE group and 10 patients in TME group. In LE group, one vaginal tear was encountered during excision of an anterior tumour, abscess complicated another patient which was followed by inter-sphincteric peri-anal fistula, and persistent bleeding per rectum has led another patient to undergo salvage proctectomy. In TME group, three patients were encountered by ileus which resolved by supportive treatment, three suffered from leakage and collection which was managed by interventional techniques, and two suffered from surgical site infection which was managed by antibiotics according to culture and sensitivity. One patient experienced postoperative bleeding and hematoma which mandated re-operation.

Late complications reported in local excision group was two, one of them was severe colitis near the site of excision (as diagnosed by colonoscopy) and was managed by medical treatment. Left ureteric injury, pelvic abscess, and anovaginal fistula have complicated a secondary TME after local excision; the patient did not undergo definitive fistula surgery yet and is still retaining her ileostomy. In TME group, late complications rate 33.3%. Two male patients suffered from sexual dysfunction, and four patients showed anastomotic stricture which required multiple sessions of anal dilatation, two of them required revision of colo-anal anastomosis with uneventful postoperative course. No operative related mortality was encountered in both groups.

In LE, six patients showed pCR (21.4%). Only one patient of pCR showed metastatic relapse. Pathologic partial response was in 15 patients of LE group, they were counselled for completion TME but refused, and only two patients accepted completion surgery. Of the 15 patients, 9 showed no recurrence, while 6 patients relapsed (4 local recurrences, one distant and a very early synchronous local and distal recurrence at 3 months). Of the six patients who relapsed, three patients had R1 resections. Near-complete pathologic response was evident in 7 patients of LE group; none of them developed local or distal relapses. In TME group, nine patients showed pCR (50%); only one of them developed relapse in the form of synchronous local and metastatic disease.

During median follow-up period of 40.5 months (range: 7–84 months) of LE patients, a total of eight patients suffered from relapse. Five patients showed local recurrence within time periods: 8, 18, 19, 27, and 29 months. Four patients died (two with local recurrences) with survival rate (85.2%). In addition, all patients of completion TME are alive and cancer-free till the last follow-up. While the median follow-up period of TME group was 30 months (range: 5–81 months), a total of five recurrences were reported: one local recurrence (with cancer-free interval reaching 59 months), three metastatic, and an early synchronous local and metastatic recurrence (at 7 months). Mortality was reported in one patient of local recurrence, with survival rate (94.4%). No statistically significant difference in relapses and mortality between the two study groups (p = 0.953 for overall recurrence, p = 0.227 for local recurrence, p = 0.365 for distal recurrence, and p = 0.634 for mortality rate).

Survival

Our study has achieved a combined median DFS of 64.23 months, with 2-year DFS 87.9% and 5-year DFS 64.9%. By analysing independent factors that impact DFS, it was concluded that full thickness and complete local excision/R0 TME resections are the only independent factors affecting DFS (p < 0.001 for complete excision/R0 versus incomplete/R1 and p = 0.013 for full thickness versus partial thickness excision) (Table 3). No statistically significant difference in DFS between both treatment groups (p = 0.692) (Fig. 2).

Our study has achieved a combined median OS of 74.46 months, with 2-year OS 94.8% and 5-year OS 81.02%. By analysing the independent factors that affect OS, it was concluded that full thickness and complete local excision/R0 TME resections, in addition to complete or near complete pathologic response (evident in ypT0/ypT1 stage), are the only independent factors affecting OS (p = 0.004 for complete excision/R0 versus incomplete/R1, p = 0.002 for full thickness versus partial thickness excision, and p = 0.017 for ypT stage) (Table 3). No statistically significant difference in overall survival was observed (80% versus 87% for LE and TME, respectively, p = 0.54), with tendency of better OS with TME group (Fig. 3).

Neither neoadjuvant type, nor the surgical approach for each technique, nor the postoperative morbidities had a statistically significant impact on DFS and OS (Table 3).

Functional Outcomes

Our study has achieved a stoma-free rate of 89.1%, only 5 patients did not reverse the stomas (3 ileostomies, in addition to two colostomies: one of them was done due to intractable incontinence, and the other was Hartmann’s after difficult pelvic dissection in a secondary TME).

Low anterior resection syndrome score for bowel function and faecal continence was fulfilled for twenty patients of LE group and twelve patients of the TME group. Half of patients of LE group showed minor LARS score. Five showed no LARS, and five patients reported major LARS. While more than half of patients of TME showed minor LARS, four reported no LARS and one patient experienced major LARS. No statistically significant difference in LARS score was observed between LE and TME (p = 0.798).

Patient satisfaction and quality of life were evaluated by QoL-EORTC questionnaire. For LE group, more than one-third of responded patients reported good quality of life (scores 6 and 7), and other factors shared in low QoL scores (3–5) in LE group, as patients’ advanced age and relatively higher co-morbidities. While for TME group, more than half of responded patients reported good quality of life (score 6 and 7), and less patients showed lower scores (3–5). No significant difference was observed in QoL between LE and TME groups (p = 0.799).

Discussion

In our study, both groups have received upfront therapy (either chemoradiation or short-course radiotherapy after induction chemotherapy), placing it in the short list of studies that addressed that topic. Our results concluded that neither short-course nor long-course chemoradiation had a statistically significant impact on survival for both groups with a tendency of more pCR rates with long course, which is consistent with the published literature [12].

Median time interval to surgery after neoadjuvant was not significant between both groups (12 weeks for LE versus 10 weeks for TME, p = 0.22), that is longer than the traditional optimal time (6–8 weeks for long-course chemoradiation and next week for short course), due to long waiting lists especially in UK subset of patients. Recent studies suggest that extending wait time after long-course chemoradiation is linked to increasing pCR rates, but with still unknown impact on survival [13].

MRI evaluation after neoadjuvant showed controversial results. Complete clinical response (mrTRG1) was evident in 10 patients out of 20 in LE group (50%). Three of them were true pathologic responders. As regards TME group, four out of 15 patients (26.7%) showed complete clinical response (mrTRG1). Three of them were true pathologic responders. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in detecting actual pathologic responders was 42.8%. So, the surgical decision was based on combined clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic assessment, which is consistent with the literature [14, 15].

Only one patient showed a residual positive lymph node in the TME specimen. This theoretically implies that eleven patients (after excluding seven patients of TME specimen ypT2/T3N0) may have been spared primary TME based on the radiologic/clinical estimation of response. On the other hand, the only patient of primary TME group that showed ypN1 was ypT0. This means leaving a residual positive lymph node if LE was implemented.

One of secondary TME patients showed ypT3 tumour in LE specimen, this was followed by completion surgery which was complicated by left ureteric injury and anovaginal fistula, while the final pathology specimen showed no residual cancer in lymph nodes (ypN0). This situation is what was reported in literature as “unnecessary” completion TME [16].

Our study showed combined pCR rate of 32%, which lies in range of pCR rates reported in literature [8, 9]. Correlating pCR to survival outcomes in rectal cancer is still a controversy [17]. Our data implied that pCR stands for better oncologic outcome, especially overall survival, but does not affect local recurrence or disease-free survival as long as R0/complete resection is achieved; this finding was confirmed by a former systematic review by Martin ST et al. and a recent study by Karagkounis et al. The latter showed poorer survival for non-responders and R1 resections [18, 19].

We reported no significant differences in LARS scores between LE and TME. The prevalence of LARS after LE in literature was reported in up to 55%; neoadjuvant radiotherapy, female gender, and specimen size were identified as independent risk factors [20]. No statistically significant difference was noted between the two study groups for the satisfaction, body image, capabilities, and defecatory function. Using the same questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), Ambrosio and colleagues scoped QoL in their study and concluded similar results [21, 22].

Conclusion and Recommendations

Our study showed that local excision of good responding rectal cancers after neoadjuvant chemoradiation showed comparable oncologic outcomes to traditional rectal resection by total meso-rectal excision, while failed to prove superiority in terms of defecatory function. Still, LE provides lesser operative morbidity, shorter operative time, and hospital stay. The limited accuracy of imaging tools hinders optimal selection of candidates of this conservative approach, in addition to the possibility of completion radical surgery which is more complicated than primary resection, faced by a higher rate of refusal from the patients, and based on certain findings; unnecessary.

LE seems a good alternative to radical rectal resection in carefully selected responders to neoadjuvant therapy (especially frail patients with good anorectal function in which radial resection would be of high morbidity) after thorough pre-operative evaluation, planning, and patient counselling. However, more well-constructed randomized studies are waited for standardizing this approach.

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations including small sample size, non-randomization, heterogenous groups in which some patients received neoadjuvant long-course chemoradiation and others received short-course RT, and missed some reliable radiological data, e.g. pretherapy MRI staging was not done in seven patients and only CT was done, due to logistic issues. In addition, mrTRG was not assigned in all situations and with variable interpretations. There were delays of date of index surgery due to logistic issues, pTRG was not assigned in all specimens, and missed some follow-up data.

References

Bosset J, Collette L, Calais G et al (2006) Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 355(11):1114–1123. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa060829

van Gijn W, Marijnen C, Nagtegaal I et al (2011) Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol 12(6):575–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70097-3

Snijders H, Wouters M, van Leersum N et al (2012) Meta-analysis of the risk for anastomotic leakage, the postoperative mortality caused by leakage in relation to the overall postoperative mortality. Eur J Surg Oncol (EJSO) 38(11):1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2012.07.111

Cornish J, Tilney H, Heriot A, Lavery I, Fazio V, Tekkis P (2007) A meta-analysis of quality of life for abdominoperineal excision of rectum versus anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 14(7):2056–2068. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9402-z

Gerard J, Rostom Y, Gal J et al (2012) Can we increase the chance of sphincter saving surgery in rectal cancer with neoadjuvant treatments: lessons from a systematic review of recent randomized trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 81(1):21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.02.001

Kim D, Lim S, Kim D et al (2006) Pre-operative chemo-radiotherapy improves the sphincter preservation rate in patients with rectal cancer located within 3cm of the anal verge. Eur J Surg Oncol (EJSO) 32(2):162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2005.10.002

Peeters K, van de Velde C, Leer J et al (2005) Late side effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: increased bowel dysfunction in irradiated patients—a Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol 23(25):6199–6206. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.14.779

Garcia-Aguilar J, Renfro L, Chow O et al (2015) Organ preservation for clinical T2N0 distal rectal cancer using neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and local excision (ACOSOG Z6041): results of an open-label, single-arm, multi-institutional, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 16(15):1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00215-6

Rullier E, Rouanet P, Tuech J et al (2017) Organ preservation for rectal cancer (GRECCAR 2): a prospective, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 390(10093):469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31056-5

Maas M, Beets-Tan R, Lambregts D et al (2011) Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 29(35):4633–4640. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.37.7176

Rullier E, Vendrely V, Asselineau J et al (2020) Organ preservation with chemoradiotherapy plus local excision for rectal cancer: 5-year results of the GRECCAR 2 randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 5(5):465–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30410-8

Wang X, Zheng B, Lu X et al (2018) Preoperative short-course radiotherapy and long-course radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of long-term survival data. PLoS ONE 13(7):e0200142. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200142

Macchia G, Gambacorta M, Masciocchi C et al (2017) Time to surgery and pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer: a population study on 2094 patients. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 4:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctro.2017.04.004

Memon S, Lynch A, Bressel M, Wise A, Heriot A (2015) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of MRI and endorectal ultrasound in the restaging and response assessment of rectal cancer following neoadjuvant therapy. Colorectal Dis 17(9):748–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12976

Sclafani F, Brown G, Cunningham D et al (2017) Comparison between magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and pathology in the assessment of tumour regression grade (TRG) in rectal cancer (RC). Ann Oncol 28:v170–v171. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx393.030

Calmels M, Collard M, Cazelles A, Frontali A, Maggiori L, Panis Y (2020) Local excision after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus total mesorectal excision: a case-matched study in 110 selected high-risk patients with rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 22(12):1999–2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15323

Hoendervangers S, Burbach J, Lacle M et al (2020) Pathological complete response following different neoadjuvant treatment strategies for locally advanced rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 27(11):4319–4336. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08615-2

Martin S, Heneghan H, Winter D (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 99(7):918–928. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8702

Karagkounis G, Thai L, Mace A et al (2019) Prognostic Implications of Pathological Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation in Pathologic Stage III Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg 269(6):1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002719

van Heinsbergen M, Leijtens J, Slooter G, Janssen-Heijnen M, Konsten J (2019) Quality of life and bowel dysfunction after transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal cancer: one third of patients experience major low anterior resection syndrome. Dig Surg 37(1):39–46. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496434

D’Ambrosio G, Paganini A, Balla A et al (2015) Quality of life in non-early rectal cancer treated by neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy and endoluminal loco-regional resection (ELRR) by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Surg Endosc 30(2):504–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4232-8

D’Ambrosio G, Picchetto A, Campo S et al (2018) Quality of life in patients with loco-regional rectal cancer after ELRR by TEM versus VLS TME after nChRT: long-term results. Surg Endosc 33(3):941–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6583-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Our study is approved by our Institutional Review Board, with proposal code: MD.18.05.48.R1—2018/06/28.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fareed, A.M., Eldamshety, O., Shahatto, F. et al. Local Excision Versus Total Mesorectal Excision After Favourable Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy in Low Rectal Cancer: a Multi-centre Experience. Indian J Surg Oncol 14, 331–338 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-022-01674-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-022-01674-9