Abstract

People who seek health information frequently may be more likely to meet health behavior goals; however, people use many different information sources. The purpose of this paper is to assess how different sources of health information influence likelihood of meeting cancer prevention behavior guidelines. Logistic regression of cross-sectional data from 6 years of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) was conducted. Independent variables included first source of health information, gender, age, race, education level, income, cancer history, general health, and data year; dependent variables were fruit and vegetable intake, exercise, smoking, mammography, Pap test, and colon cancer screening. Those who seek health information from doctors, the internet, or publications had higher odds of meeting more cancer prevention guidelines than those who do not seek health information. Those who used healthcare providers as an initial information source had higher odds of meeting diet, cervical, and colon cancer screening recommendations, while using the internet as an initial source of health information was associated with higher odds of meeting diet, smoking, and colon cancer screening recommendations. No health information source was associated with meeting either exercise or mammography recommendations. People should be encouraged to seek health information to help them meet their behavior goals, especially from sources that are more likely to be accurate and encourage cancer prevention behavior. Future research is needed to understand the accuracy of health information and what kinds of health information have positive influences on cancer prevention behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Various sources are used to seek for health information including the internet, print sources, family and friends, and medical providers [1]. Evidence suggests that individuals who seek and more frequently scan health information may be more likely to perform cancer prevention behaviors [2, 3]. These prevention behaviors, including diet, exercise, and smoking cessation, are associated with lowering the risk of developing cancer [4,5,6]. Additionally, individual that seek health information may be more likely to receive cancer screenings [7], increasing their chance of early cancer identification and reducing risk of death [8,9,10]. This evidence encourages information seeking as a potential mechanism to increase cancer prevention and screening behavior.

Given the benefits of health information seeking, it is encouraging that research documents an increase in the number of individuals seeking health information from any source between 2003 and 2013 [11]. However, during this time period, the sources people use to identify health information have changed; there have been increases in the percentage of adults that use the internet as a health information source [12, 13]. Despite this frequency, many distrust the accuracy of information from the internet [14, 15]. Doctors/healthcare providers remain the most trusted source of health information, despite being used as the first source of health information less often [16, 17]. Evidence suggests that people who use more trustworthy or accurate sources of health information may be more successful than others at cancer prevention behaviors [18,19,20].

As there are many information sources available providing cancer prevention advice, it is important to identify the modalities that are particularly helpful in improving cancer prevention behaviors. In 2010, Redmond et al. assessed achievement of cancer behavior recommendations by health information source, including print media, television, internet, community organizations, and friends and family using data from the 2005 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) [21]. Questions were reformulated in latter iterations of HINTS to only ask the first source of healthcare information used when people seek health information, and added doctors/healthcare providers as an information source. Redmond et al. then used 2007 HINTS data to assess those meeting healthy lifestyle goals by using doctors/healthcare providers as the first information source [21]; however, the 2007 analysis ignored sources of health information besides doctors/healthcare providers.

Thus, questions remain about the characteristics of individuals that seek any health information, those who use the internet as an information source, and whether trends continued across additional data years. The proliferation of the internet and the wider availability of health information may have altered how people find and use health information since 2007. The goal of this study is to examine how trends in health information seeking and cancer prevention behavior have changed in the past decade. To achieve this goal, we extended this prior research by Redmond et al. through the years 2011–2017. Given the prior evidence available regarding sources of health information, we hypothesize that those who seek any information and who seek information from doctors/healthcare providers first will be more successful at meeting cancer prevention recommendations, while those who do not seek health information may not meet recommendations.

Methods

Data Collection

This study used data obtained through the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) [22], sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). HINTS is fielded to a representative sample of US civilian, non-institutionalized adults over 18 years of age. HINTS collects data about how respondents seek and use information about cancer, as well as cancer risk perception, cancer prevention behavior, and demographics [23]. This study uses data from HINTS 3 (2007), HINTS 4, cycles 1 (2011), 2 (2012), 3 (2013), 4 (2014), and HINTS 5, cycle 1 (2017). The HINTS 3 survey collected data by random-digit-dialing respondents to participate in a telephone interview and also collected data using a mailed questionnaire. No differences were detected between survey administration modes based on chi-square comparison of key variables (i.e., age and gender), resulting in combining both telephone and mailed survey responses. The fourth version of HINTS was administered by mail in four separate cycles: 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014, and HINTS 5 is also administered by mail, with 2017 being the first cycle available. The survey uses a stratified postal address frame to randomly sample residential addresses. HINTS 3 had a response rate of 21% by telephone and 31% by mail in 2007, HINTS 4 had response rates of 37% in cycle 1 (2011), 40% in cycle 2 (2012), 35% in cycle 3 (2013), and 34% in cycle 4 (2014), and HINTS 5, cycle 1 (2017) had a response rate of 32% [23]. HINTS is published with survey weights to allow the results to be generalized to the population.

To facilitate comparison with the findings identified by Redmond et al. [21], our study results are presented in tables that compare the analysis for each year, as well as combining all years into a pooled cross-section. Following Redmond’s approach, we limited analyses of mammography to women > = 40 and colonoscopy to participants > = 50 to be consistent with guidelines at the time of data collection and the previous study design. Analyses controlled for gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, education level, cancer history, and general health status.

Measures

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics used in this analysis included gender (male/female), age (18–34/35–49/50–64/65–74/≥ 75), income (< $50,000/≥ $50,000), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White/non-Hispanic Black/Hispanic/Other), education (high school graduate or less/some college or more), cancer history (no history of cancer/cancer survivor), and general health (excellent/very good/good/fair/poor). Health information seeking behavior was first quantified by asking “Have you ever looked for information about health or medical topics from any source?” followed by “The most recent time you looked for information about health or medical topics, where did you go first?” [22]. Potential responses to this question included internet, doctor/healthcare provider, books, brochures/pamphlets, magazines, newspapers, family, friends/coworkers, telephone service, cancer organization, library, complementary, alternative, or unconventional medicine practitioner, television, health insurance providers, and other. These responses were categorized into five types of sources: publications (i.e., books, brochures/pamphlets, magazines, and newspapers); social network (i.e., family, friends/coworkers); internet; doctors/healthcare providers; and other (i.e., other, telephone service, cancer organization, library, television, health insurance provider, and complementary or alternative medicine practitioner) for analysis.

There were 7 dependent variables, including meeting 6 guidelines for diet, exercise, smoking, mammography, Pap test, and colonoscopy, along with a composite variable combining all eligible behaviors. The diet variable assessed whether fruit and vegetable intake recommendations were met. HINTS asked about fruit intake: “About how many cups of fruit (including 100% pure fruit juice) do you eat or drink each day?” and an identically worded question for vegetable intake [22]. If servings equaled 5 or more cups of fruits and vegetables combined, participants met guidelines. For physical activity: “In a typical week, how many days do you do any physical activity or exercise of at least moderate intensity, such as brisk walking, bicycling at a regular pace, swimming at a regular pace, and heavy gardening?” and exercise on 5 days was considered meeting guidelines [22]. Smoking was assessed by: “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” with the choices of every day, some days, or not at all [22]. Those who said no to the first question, or answered “not at all” to the second question, met the smoking goal. For mammograms, after 2007 women aged 35 or more were asked “When did you have your most recent mammogram to check for breast cancer, if ever?” and any answer other than “never” for women 40 and over was considered meeting guidelines [22]. Although guidelines for mammography have changed, the majority of data collection for this study occurred when the American Cancer Society guidelines recommended women start receiving mammograms at age 40 [24]. All women answered the question: “Have you ever had a Pap Smear?” in 2007 and in 2011–2017 were asked “When did you have your most recent Pap test to check for cervical cancer?” with answers other than “never” meeting guidelines [22]. For Pap test, frequency guidelines differ by age and HPV testing status, and previous guidelines recommended different age cutoffs (testing previously recommended at age 18, now age 21 or later) [25]. Due to the change in guidelines for this variable and different frequency recommendations, researchers did not want to make a stricter cutoff for this variable. Respondents 45 or older were asked “When did you have your most recent colonoscopy to check for colon cancer?” and “When did you have your most recent sigmoidoscopy to check for colon cancer?” in 2007 [22]. For HINTS 4, colon cancer screening questions changed to “Has a doctor ever told you that you could choose whether or not to have a test for colon cancer?” followed by “Have you ever had one of these tests to check for colon cancer?” [22] There were no longer questions asking about colon cancer screening 2014 or later. Participants aged 50 and older were considered having met guidelines if they answered that they had ever had colon cancer testing. Responses to these questions were transformed into binary variables indicating whether guidelines were met or not; these became the dependent variables in our analysis. The composite variable was created by adding together the number of guidelines that participants met and dividing by the number of guidelines that participants were eligible to meet for a percentage.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses used survey weighting and jackknife variance estimations provided by HINTS [23]. Analyses were first performed using the data from 2005 (not reported) and 2007 to replicate the findings from Redmond et al. and ensure model fidelity. These analyses were then extended from 2007 across 2011–2014 and 2017.

Maintaining fidelity to the analyses conducted by Redmond et al., the data was analyzed using the same demographic categories. Weighted descriptive statistics were analyzed for participants who were included in the composite outcome category. A weighted multivariable logistic regression model was created to explore the adjusted association between the dependent variables, meeting behavioral guidelines, and the independent variable, source of health information versus no health information seeking, controlling for gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, education, cancer history, and health status. A composite outcome assessed the percentage of eligible guidelines met using restricted logistic regression. For example, a woman over 50 would be eligible for all 6 behaviors, while a 35-year-old man would be eligible only for diet, exercise, and smoking behaviors. Participants that were not eligible for meeting at least 2 guidelines (due to nonresponse for outcome variables) were excluded from analysis of the composite outcome. Participants without data for the primary independent variable of interest, health information seeking, were not included in this analysis. For all other demographic variables, missing data was included as a separate category to maximize usable data. Results were considered significant for p values less than 0.05. All analyses were completed using Stata version 14 (2015, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) in 2019.

Results

Participants

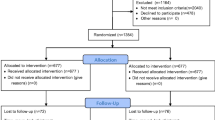

A population sample was obtained from the combined 2007, 2011–2014, and 2017 HINTS data. There was a total of 25,410 participants for these 6 data years, and 23,301 were included because they had data for the primary independent outcome of interest (Table 1). The demographic categories were consistent across years for all variables.

Health Information Sources

The percent that answered “yes” to “Have you ever looked for information about health or medical topics from any source?” ranged from 69.7% in 2007 to 79.5% in 2012. The most common sources for health information (2007–2017) were the internet (52.3%), doctors/healthcare providers (11.2%), publications (7.5%), and social networks (3.5%) (Fig. 1). All other sources, including television, complementary or alternative medicine practitioners, cancer organizations, phone services, insurance providers, and libraries combined were less than 2% of initial information sources.

Meeting Recommendations

In the combined data (2007–2017), 16.3% met fruit and vegetable recommendations, 26.0% met exercise recommendations, and 81.9% met smoking recommendations (Fig. 2). Excluding 2007, 90.4% of women above age 40 met mammography recommendations. Among women, 93.6% met Pap test recommendations. Excluding 2014 and 2017, 68.7% of respondents 50 or older had a colon cancer screening test (colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy).

Meeting Recommendations by Source of Health Information

Meeting fruit and vegetable recommendations was associated with using doctors/healthcare providers, the internet, publications, or other sources of health information compared with no information seeking (Table 2). Women, those with higher education levels, and those with higher incomes, were also more likely to meet fruit and vegetable recommendations, while those with lower self-rated health and from years after 2007 were less likely to meet recommendations (Table S1). No information sources were associated with meeting exercise guidelines, and women, those 35–49 or 75+ years old, those with race category “Other,” people with lower general health, and people in years after 2007, were less likely to meet exercise guidelines. Meeting smoking guidelines was associated with higher odds of using the internet for health information, being female, age 50 or older, being races other than White, higher income, higher education level, and being part of the 2011, 2014, or 2017 cohort.

Meeting mammogram recommendations did not have any association with health information seeking, but those in age groups over 50, Black race, those with higher incomes, those with higher education, cancer survivors, and respondents in the year 2017 had higher odds of meeting these recommendations (Table 3). Women seeking health information from doctors/healthcare providers, those age 35 or older, higher education level, and cancer survivors had higher odds of meeting Pap test recommendations, while those in the race category “Other” were less likely to meet these recommendations (Table S2). Individuals who used the internet, doctors/healthcare providers, or publications for health information, people 65 or older, those with higher incomes, those with higher education levels, cancer survivors, and survey respondents from years 2011, 2012, and 2013 had higher odds of meeting colon cancer test recommendations, while women had lower odds than men. For the composite outcome, those using the internet, doctors/healthcare providers, or publications for health information had higher odds of meeting a greater percentage of guidelines compared with those who do not seek health information. Women, those age 50 or older, Hispanic people, those with a higher income, those with a higher education level, and cancer survivors, had higher odds of meeting multiple guidelines, while those with lower general health and in years after 2007 had lower odds of meeting multiple guidelines.

Discussion

Despite the availability of multiple sources that individuals can use to seek health information, achieving health behavior change remains a challenge. To examine whether the altered landscape of health information has affected health behaviors, we investigated the relationship between health information seeking behavior and cancer prevention behaviors. Briefly, we found that those seeking health information from the internet, doctors/healthcare providers, or publications were more likely to meet a higher number of cancer prevention guidelines compared with those that do not seek information.

We found that recommendations for fruit and vegetable consumption, smoking avoidance, screening for cervical cancer, screening for colon cancer, and the composite of all behaviors had higher odds of being met among people seeking health information from at least one source compared with those who do not seek health information. As both behaviors that are associated with lower risk of developing cancer [4,5,6] and behaviors that screen for cancer [8,9,10] may prevent cancer death, it is important that people attempt to meet these recommendations. As health awareness has been tied to prevention behaviors in prior research [2, 26], the 20–30% of people who did not seek health information at all may not meet recommendations if they are not aware of recommendations. To improve awareness about prevention behaviors, health professionals should seek ways to communicate with those that do not seek health information on their own.

Using health providers as an initial source of information was associated with increased odds of meeting diet, Pap test, and colon cancer screening guidelines, adjusted for demographics. There may be a relationship between age and utilizing healthcare providers as information sources, as both Pap test and colon cancer guidelines had higher odds of being met by older adults, and previous research has shown that all age groups have higher odds of talking to doctors/healthcare providers as a first source of health information compared with 18–45-year-olds [18]. There is a plethora of diet information available from all information sources, but there is evidence that exposure to conflicting nutrition information leads to confusion, distrust of recommendations, and decreased fruit and vegetable consumption [27, 28]. While some sources may provide a variety of potentially contradictory nutrition advice, health professionals may be more likely to recommend diet behaviors that help with cancer prevention [29].

There were no associations between meeting exercise recommendations and health information seeking. A wide range of sources may be used by those meeting exercise recommendations, and prior research indicates that publications and social networks were more frequently used by those meeting these recommendations rather than health professionals, though even those sources were not significant in our results [26]. There is evidence that both diet and physical activity behavior are socially influenced [30,31,32]; if people are more likely to eat vegetables and exercise if friends and family do, they may not exercise due to health information acquired but rather because of social reasons. Those who are more likely to be health information seekers may also have overlapping qualities with those who are less likely to exercise. Prior evidence shows that women, cancer survivors, and those who do not have a usual place of healthcare are more likely to be information seekers, and these demographic categories may also be less likely to exercise [33, 34].

Unlike in the previous analysis by Redmond, et al., no health information source was associated with meeting the mammography recommendations, while meeting Pap test recommendations was associated with doctors/healthcare providers as a source of health information [21]. Meeting Pap test guidelines was not more likely among those seeking information from any other source, and was not associated with seeking information from health providers in 2007 in the paper by Redmond et al. [21]. The majority of women were meeting mammography and Pap test recommendations, and a small percentage who were not meeting these recommendations may have barriers to screening that are not related to information seeking behavior or knowledge of recommendations.

Limitations to this analysis are inherently related to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Trends over time cannot be examined in individuals, only in populations, so changes in behavior or preferred information source cannot be established. There may be recall bias; people may not remember having received certain screenings or using certain information sources. In addition, poor health literacy may also lead to bias if participants do not know what a specific screening test is called. Assessment of meeting guidelines is difficult over 10 years of cross-sectional data, as some guidelines have changed, namely Pap test and mammography guidelines [24, 25]. To maintain fidelity to the original study and because the majority of data collection occurred before the mammography guideline changed, women 40 or over rather than 50 or over were included in this analysis for mammography. Finally, another limitation is the lack of data about the legitimacy of information sources, as print sources, the internet, and interpersonal sources widely vary in accuracy.

Conclusion

In a nationally representative sample, seeking information was associated with higher odds of meeting cancer prevention and screening behaviors, including fruit and vegetable consumption, not smoking, and screening for cervical and colon cancer. Additionally, using healthcare providers as an initial information source was associated with higher odds of meeting diet, cervical, and colon cancer screening recommendations. Using the internet as an initial source of health information was associated with higher odds of meeting diet, smoking, and colon cancer screening recommendations. No health information source was associated with meeting either exercise or mammography recommendations. While people should be encouraged to seek health information in general, it is important for people to seek information from sources that are more likely to be accurate and encourage cancer prevention behaviors.

Data Availability Statement

This study uses publicly available data from the National Cancer Institute at hints.cancer.gov.

References

Blanch-Hartigan D, Viswanath K (2015) Socioeconomic and sociodemographic predictors of cancer-related information sources used by cancer survivors. J Health Commun 20(2):204–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.921742

Hornik R, Parvanta S, Mello S, Freres D, Kelly B, Schwartz JS (2013) Effects of scanning (routine health information exposure) on cancer screening and prevention behaviors in the general population. J Health Commun 18(12):1422–1435. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.798381

Shim M, Kelly B, Hornik R (2006) Cancer information scanning and seeking behavior is associated with knowledge, lifestyle choices, and screening. J Health Commun 11(Suppl 1):157–172

Kabat GC, Matthews CE, Kamensky V, Hollenbeck AR, Rohan TE (2015) Adherence to cancer prevention guidelines and cancer incidence, cancer mortality, and total mortality: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 101(3):558–569. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.094854

Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V, Collaborators MWS (2013) The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 381(9861):133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6

Thomson CA, McCullough ML, Wertheim BC, Chlebowski RT, Martinez ME, Stefanick ML et al (2014) Nutrition and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines, cancer risk, and mortality in the women’s health initiative. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 7(1):42–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0258

Shneyderman Y, Rutten LJ, Arheart KL, Byrne MM, Kornfeld J, Schwartz SJ (2016) Health information seeking and cancer screening adherence rates. J Cancer Educ 31(1):75–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0791-6

Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M (2014) Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ 348:g2467. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2467

Landy R, Pesola F, Castañón A, Sasieni P (2016) Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case-control study. Br J Cancer 115(9):1140–1146. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.290

Nelson HD, Fu R, Cantor A, Pappas M, Daeges M, Humphrey L (2016) Effectiveness of breast cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis to update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med 164(4):244–255. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0969

Finney Rutten LJ, Agunwamba AA, Wilson P, Chawla N, Vieux S, Blanch-Hartigan D, Arora NK, Blake K, Hesse BW (2016) Cancer-related information seeking among cancer survivors: trends over a decade (2003-2013). J Cancer Educ 31(2):348–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0802-7

Fox S (2011) Health topics: 80% of internet users look for health information online. Pew Research Center. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/HealthTopics.aspx. Accessed 8 Mar 2019

Prestin A, Vieux SN, Chou WY (2015) Is online health activity alive and well or flatlining? Findings from 10 years of the Health Information National Trends Survey. J Health Commun 20(7):790–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018590

Sbaffi L, Rowley J (2017) Trust and credibility in web-based health information: a review and agenda for future research. J Med Internet Res 19(6):e218. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7579

Benigeri M, Pluye P (2003) Shortcomings of health information on the Internet. Health Promot Int 18(4):381–386

Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, Viswanath K (2005) Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med 165(22):2618–2624

Shea-Budgell MA, Kostaras X, Myhill KP, Hagen NA (2014) Information needs and sources of information for patients during cancer follow-up. Curr Oncol 21(4):165–173. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.21.1932

Volkman JE, Luger TM, Harvey KL, Hogan TP, Shimada SL, Amante D et al (2014) The National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey [HINTS]: a national cross-sectional analysis of talking to your doctor and other healthcare providers for health information. BMC Fam Pract 15:111. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-111

Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou WY, Prestin A (2014) Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res 16(7):e172. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3117

Moldovan-Johnson M, Martinez L, Lewis N, Freres D, Hornik RC (2014) The role of patient-clinician information engagement and information seeking from nonmedical channels in fruit and vegetable intake among cancer patients. J Health Commun 19(12):1359–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.906521

Redmond N, Baer HJ, Clark CR, Lipsitz S, Hicks LS (2010) Sources of health information related to preventive health behaviors in a national study. Am J Prev Med 38(6):620–627.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.001

National Cancer Institute (2019) HINTS survey instruments. http://hints.cancer.gov/instrument.aspx. Accessed 8 Mar 2019

National Cancer Institute (2019) Frequently asked questions about HINTS. http://hints.cancer.gov/faq.aspx. Accessed 22 July 2019

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih YC, Walter LC, Church TR, Flowers CR, LaMonte S, Wolf AM, DeSantis C, Lortet-Tieulent J, Andrews K, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Smith RA, Brawley OW, Wender R, American Cancer Society (2015) Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA 314(15):1599–1614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12783

Feldman S (2011) Making sense of the new cervical-cancer screening guidelines. N Engl J Med 365:2145–2147. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1112532

Ramírez AS, Freres D, Martinez LS, Lewis N, Bourgoin A, Kelly BJ, Lee CJ, Nagler R, Schwartz JS, Hornik RC (2013) Information seeking from media and family/friends increases the likelihood of engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors. J Health Commun 18(5):527–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.743632

Nagler RH (2014) Adverse outcomes associated with media exposure to contradictory nutrition messages. J Health Commun 19(1):24–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.798384

Lee CJ, Nagler RH, Wang N (2018) Source-specific exposure to contradictory nutrition information: documenting prevalence and effects on adverse cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Health Commun 33(4):453–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1278495

Demark-Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, Thomson CA, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, Stout NL, Kvale E, Ganzer H, Ligibel JA (2015) Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 65(3):167–189. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21265

Sirard JR, Bruening M, Wall MM, Eisenberg ME, Kim SK, Neumark-Sztainer D (2013) Physical activity and screen time in adolescents and their friends. Am J Prev Med 44(1):48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.054

Simpkins SD, Schaefer DR, Price CD, Vest AE (2013) Adolescent friendships, BMI, and physical activity: untangling selection and influence through longitudinal social network analysis. J Res Adolesc 23(3):537–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00836.x

Graham DJ, Pelletier JE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lust K, Laska MN (2013) Perceived social-ecological factors associated with fruit and vegetable purchasing, preparation, and consumption among young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 113(10):1366–1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.06.348

Huerta TR, Walker DM, Johnson T, Ford EW (2016) A time series analysis of cancer-related information seeking: hints from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 2003-2014. J Health Commun 21(9):1031–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1204381

Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Hesse B (2006) Cancer-related information seeking: hints from the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Health Commun 11(Suppl 1):147–156

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect the National Cancer Institute.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 37.1 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Swoboda, C.M., Walker, D.M. & Huerta, T. Odds of Meeting Cancer Prevention Behavior Recommendations by Health Information Seeking Behavior: a Cross-Sectional HINTS Analysis. J Canc Educ 36, 56–64 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01597-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01597-0