Abstract

Malawi has the highest incidence of cervical cancer in the world. Due to various challenges the country faces in terms of cervical cancer control, women have a poor chance to survive this disease. The purpose of our study was to describe the knowledge and practices of cervical cancer and its screening as well as the educational preferences of women living in a rural community in the Chiradzulu District. We conducted a survey among women between the ages 30 and 45, used convenience sampling, a calculated sample size (n = 282) and structured interviews to collect the data. A questionnaire adapted from a previous study served as data collection instrument. The data were analysed in Microsoft Excel and chi-square (p < .05) was used to investigate the relationships between the variables. Content analyses analysed the open-ended questions. The mean age of the sample was 36.1 (SD ± 5.1) and the highest percentage (37.4%; n = 98) belonged to the Yao ethnic group. The majority attended primary school (66.0%; n = 173), were married (74.4%; n = 195) and depended on a small business as source of income (55.7%; n = 146). Most of the women (93.4%; n = 247) had heard of cervical cancer and the visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) screening programme (67.9%; n = 178) but only 22.9% (n = 60) indicated they had been screened. Lack of knowledge of the screening programme was the most common reason for not being screened. Having a demonstration of the VIA procedure was the most popular educational method (92.0%; n = 241) which gives a fresh approach to educational programmes aimed at preventing cervical cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a significant universal public health problem, with an estimated mortality rate of 50.4% worldwide. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women and the seventh overall, with about 85% of women suffering from this disease living in the less developed regions of the world. Africa is considered to have high-risk regions, specifically Eastern, Southern and Middle Africa [1]. Malawi, which forms part of Southern Africa, has the highest incidence and mortality rate of cervical cancer in the world. The incidence age-standardised rate (ASR) is 75.9 per 100,000 population and the mortality rate 49.8 per 100,000. In addition, cervical cancer accounts for 45.5% of all cancers in Malawian women [2]. Each year, an estimated 3684 women are newly diagnosed with this disease whilst causing the deaths of 2314 [3]. According to Anorlu [4], 60 to 75% of women diagnosed with cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa live in rural areas, which adds to the high mortality rates. This situation is not limited to sub-Saharan Africa, as Palacio-Mejía and others [5], in a study conducted in Mexico, found that women living in rural communities have a lesser chance of surviving cervical cancer compared to those living in urban communities.

The primary cause of cervical cancer is persistent infection with one or more of the oncogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV), usually types 16 and 18 are found in most cervical cancers. In addition, cervical cancer is an AIDS-defining cancer, meaning women with HIV and AIDS have a high risk of developing this disease due to having more persistent HVP infections. Women suffering from HIV and AIDS also develop cervical cancer earlier than those not infected with HIV [6]. Other factors such as tobacco smoking, co-infection with other sexually transmitted diseases, long-term use of oral contraceptives, high parity, early sexual onset, multiple sexual partners and having sexual intercourse with partners with multiple sexual partners add to the risk for developing cervical cancer [7].

Cervical cancer is a preventable and treatable disease if detected early. Despite being a life-threatening condition, screening has been known to reduce cervical cancer morbidity and mortality dramatically [8]. Various methods are used to screen for cervical cancer of which the Pap smear is the best known; however, other methods including visual tests such as visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), also known as direct visual inspection (DVI), are also used. Similar to the Pap smear, VIA requires a speculum examination to expose the cervix and the external os, where after 3 to 5% acetic acid is applied to the cervix to identify abnormal areas which would have a distinct white appearance. VIA is inexpensive and can be performed with modest equipment, does not require laboratory infrastructure and can be implemented in a wide range of settings by trained nurses, midwives and doctors. VIA provides immediate results allowing the provision of treatment, such as cryotherapy, during the same visit [9].

Malawi initiated a cervical cancer-screening programme in 2004. A single visit approach was selected to screen women for cervical cancer as it allows screening and initial management during the same visit. The screening programme targets women aged 30 to 45 and offers VIA and cryotherapy or referral to other services should the woman be VIA positive. The screening programme recommends that women who are VIA negative are screened at least every 5 years, whilst those who were VIA positive and received subsequent treatment are screened 1 year after the initial screening [10]. According to Mysamboza and colleagues [2], VIA is offered at more than 130 public health facilities across the country and is free of cost [11]. The programme’s target was set at screening 80% of the eligible population within 5 years, which has not been realised. However, according to Maseko and others [8], screening increased from 9.3% of the target population in 2011 to 26.5% at the end of 2015. The ICO/IARC HPV Centre [12] fact sheet published in 2017 reported only 2.6% of all women aged 25 to 64 years old are screened every 3 years.

In addition to the low screening uptake, Malawi faces various other challenges in terms of cervical cancer control. Women suffering from this disease are young and present with later-stage disease, most commonly inoperable. Curative treatment options are limited due to the scarcity of pathological services and surgery and the absence of radiotherapy. Women have a poor chance to survive this disease and a 5-year survival rate of 2.9% has been reported, which is much lower than the 26.5% 5-year survival rate reported in Zimbabwe and the 17.7% in Uganda [6]. In addition, it does not seem as if palliative care services reach all patients resulting in many women dying in miserable conditions [13]. Considering these circumstances, preventative measures seem the only logical alternative. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe the knowledge and practices of cervical cancer and its screening in women living in a rural community in the Chiradzulu District in Malawi. As this study was part of a larger study aimed at developing and testing an educational programme to improve screening utilisation, the respondents’ teaching preferences were also investigated.

Methods

The study setting was Chiradzulu District in Southern Malawi. Chiradzulu is a rural district hosting a population of 288,546 of which 153,200 are women, of whom 23% are in childbearing age [14]. The district has a small urban centre near Blantyre, Malawi’s commercial capital but more than 90% of people live in rural areas. Land is scarce and 97% of households reported an average per capita income of less than 1USD per day [15]. Chiradzulu district is served by 11 health centres that provide primary healthcare free of cost and one second level hospital. In addition to the hospital and clinic staff, health surveillance assistants, trained by hospital staff, provide community outreach services such as health education and vaccines [16]. Women in Malawi are generally not well educated; 15% of women never attended school, 56% have some primary education and 9% complete primary school; rural women are less educated than urban women [17]. People living in Chiradzulu District also consult traditional healers and use local herbs, which could delay them from seeking healthcare. The commonest means of transport in this district are bicycles.

After obtaining ethical clearance (M151043 and P.02/16/1892) and permissions from the district governance structures, we conducted a survey among women between the ages 30 and 45, living within a 5-km radius from the Chiradzulu District hospital. Convenience sampling was used to select the sample as it allowed us to include women who were readily available [18]. The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft ® sample calculator. The population was 820, margin error 5%, confidence interval 95% and response distribution 50%, which resulted in a sample size of 262 (n = 262). Structured interviews were conducted to collect the data. The data collection instrument was adapted from a questionnaire developed to investigate men’s knowledge of cervical cancer [19], translated into the local Chichewa language. The questionnaire consisted of open- and closed-ended questions and were divided into sections allowing us to collect socio-demographic data as well as data regarding knowledge of cervical cancer, the VIA screening programme, screening practices and teaching preferences. Women meeting in central places, such as water boreholes, maize mills, clinics, markets, homes and churches, were recruited. An information leaflet was handed to those recruited and the study was explained to them. It was also explained to the women that by taking part in the survey, it would be deemed they had consented to participate in the study. Data were collected between May and June 2016 and continued until the sample size was realised. Completed questionnaires were placed in a sealed box, numbered sequentially and entered onto an Excel spreadsheet. The data were analysed in Microsoft Excel and the chi-square test of independence (p < 0.05) was used to investigate the relationships between the variables. Content analyses were used to analyse the open-ended questions [18].

Results

The mean age of the sample was 36.1 (SD ± 5.1) and the median age 35 years. The women belonged primarily to the Yao ethnic group (37.4%; n = 98). The majority attended primary school (66.0%; n = 173), were married (74.4%; n = 195) and more than half (55.7%; n = 146) depended on a small business as source of income. The reported monthly personal income ranged from 0 to 200,000 Malawian Kwacha (MK) (± 274 USD) per month, on average 15,909 MK (21.8 USD) which is below the Malawi poverty line of 1.25 USD per day (Hami et al. 2014). The number of dependents depending on this income ranged from 0 to 11 with an average of 4.6 (Table 1).

When the respondents were asked whether they had ever heard of cervical cancer, the majority (94.3%; n = 247) responded positively, whilst 5.7% (n = 15) said they had never heard of this disease. On asking those who had ever heard of cervical cancer whether they think they are at risk for developing this disease and whether cervical cancer can be cured if detected early, 90.3% (n = 223) responded yes to cure, but only 56.9% (n = 149) acknowledged their risk. The chi-square test of independence did not find a significant relationship between risk perception and age (p = 0.240) and risk perception and having ever been screened (p = 0.301).

On asking the same respondents what the causes of cervical cancer could be, 25.9% (n = 64) said they did not know, whilst 2.8% (n = 7) indicated that they had forgotten. Having multiple sex partners was the most well-known cause (23.9%; n = 59), followed by having many children (9.7%; n = 24); HPV was not mentioned at all (Table 2). When comparing knowledge of the causes of cervical cancer and having ever been screened, the chi-square test of independence did not find a significant relationship between the variables (p = 0.403).

To investigate whether the respondents knew the warning signs of cervical cancer, we asked them what changes in their bodies would make them think they have cancer of the mouth of the womb. Abnormal vaginal bleeding was the most common symptom identified (35.6%; n = 88), followed by a foul smelling vaginal discharge (24.3%; n = 60) (Table 2). When comparing knowledge of the symptoms and having ever been screened, no significant relationship was found (p = 0.350).

To investigate knowledge of the screening programme, we asked the respondents whether they had ever heard of the VIA screening programme to check up for cancer of the mouth of the womb. Most of the respondents (67.9%; n = 178) indicated they had heard of the screening programme, whilst 32.1% (n = 84) said they had never heard of such a programme. The chi-square test of independence did not find a statistical significant relationship between having ever heard of VIA and age (p = 0.240), but a significant relationship was found between having ever heard of VIA and educational level (p = 0.004). On asking those who had heard of the screening programme to give some information on what they knew about it, 42.1% (n = 75) said they did not know, followed by to detect and treat cervical cancer (13.5%; n = 24). Table 3 presents the details pertaining to what the respondents knew about the screening programme.

To investigate screening practices, we asked the respondents whether they had ever been screened and if not, what the reason for not being screened could be. Only 22.9% (n = 60) indicated they had been screened, whilst the majority (77.1%; n = 202) indicated they had never been screened. There was no statistically significant relationship between having been screened and having heard of VIA (p = 0.301) and having been screened and believing that cervical cancer could be cured if detected early (p = 0.158). Lacking information about the screening programme was the most common reason for not being screened (29.2%; n = 59), followed by being too lazy to go for screening (17.8%; n = 36). A small percentage (4.5%; n = 9) reported they presented for screening but were not screened due to reasons such as lack of equipment (Table 3). When asked whether they would indeed be willing to be screened if told the VIA is simple, painless and good for early detection of cervical cancer, 96.6% (n = 253) of respondents said they would have the screening, whilst 3.4% (n = 9) indicated they would not be prepared to be screened. These women represented the Ngoni, Yao and Lomwe ethnic groups; three had never heard of cervical cancer, whilst three who had ever heard of cervical cancer believed it cannot be cured.

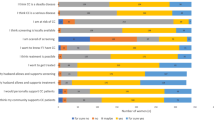

When asking the respondents about their teaching preferences, they could choose between “yes” and “no” to indicate whether they would like to be educated by means of flip charts, posters, a model of the pelvis, a demonstration of the VIA procedure, a drama and video or mobile phones. Having the VIA procedure demonstrated to them was the most popular choice (92.0%; n = 241), followed by posters (81.7%; n = 214), a drama (79.0%; n = 207), flip charts and using a model of a pelvis 76.0% (n = 199); videos and mobile phones were the least chosen (61.1%; n = 160). The preferred time for the teaching was also investigated and women could choose between 0900 to 1100, 1000 to 1200 and 1400 to 1600. Having an educational session in the afternoon was the most popular and selected by 75.2% (n = 197) of the respondents.

Discussion

When comparing the socio-demographical information of our respondents to the Malawian Country Profile [20], the profile of the women was similar in terms of educational level and income but differed in terms of ethnic group representation and economic activity. The highest percentage of our respondents represented the Yao ethnic group and depended on small businesses, whilst the Chewa represented most of the Malawian population. Agriculture is the largest economic activity in the country. Our study revealed that 4.6 people on average depended on the income of the respondents, which is slightly higher than the 4.4 children per woman reported by the World Bank [21]. However, not only children may be dependent on the respondents’ income, which could be responsible for the slightly higher figure.

It was positive to find that more than 90% of the women had heard of cervical cancer, which was higher than the 82.5% reported in another Malawian study [8] and the 78% found in a Kenyan study [22]. What is less positive is that only 56.9% of the women were aware of their risk to develop cervical cancer. Although other studies [8, 23] report better results, our findings compare positively to the Malawian study of Hami and colleagues [11], who found only 5.8% of their sample believed they might have cervical cancer. Irrespective of the higher percentage of women in our study who were aware of their risk, it is still of great concern as women who believe they are not susceptible to cervical cancer could be less likely to use screening opportunities, which deprives them from having abnormalities detected and treated when cure is still possible [23]. What is positive is the finding that more than 90% of the respondents were prepared to have screening if they had more information and were reassured the procedure is not painful. Whether their preparedness to be screened would indeed lead to screening is debatable, as seen in our study, there is no positive relationship between having knowledge of screening and being screened. Sheeran and Orbell [24] found that women who have formed implementation intentions, such as having planned where and when they would be screened, are more likely to have screening compared to those who also intended screening but did not form implementation intentions. Another benefit of implementation intentions is that it also weakens previous delay behaviour. Therefore, it might be of benefit to ask women to write down which screening clinic is nearest to them, how they would get to the clinic and when they plan to have the screening during education campaigns to alert women to cervical cancer and screening opportunities.

Knowledge of the causes of cervical cancer was low. For instance, nobody mentioned the HPV, and all the other possible causes, except for having many sex partners, were identified by less than 10% of the respondents. Lacking knowledge of the HPV as cause of cervical cancer is not limited to our study, as Hami and others [11] found a similar trend as 96.8% of their respondents did not identify the HPV. A low level of knowledge about the other contributing factors relating to cervical cancer was also found in the study of Hami and others [11] and Maseko and colleagues [8]. What is interesting is that a small percentage of women in the current study believed that inserting herbs into the vagina can cause cervical cancer; these beliefs are not limited to Malawi, but seem to be shared among people living in Africa.

Abnormal vaginal bleeding was the most known symptom of cervical cancer among the women in our study, with 35.6% of respondents mentioning it. Getahun and others [25], when investigating Ethiopian women’s knowledge of cervical cancer, found the same trend as 42.9% of the women in their study mentioned some form of abnormal bleeding as a symptom. A foul smelling vaginal discharge was the second commonly known symptom in our study and that of Getahun and colleagues [25], but better known in the latter (35.3%) compared to 24.3% in the former. However, more women in the Ethiopian study (39.6%) said they did not know any symptom of cervical cancer compared to the 29.1% in our study. As seen in the current study, there was no link between knowledge of the symptoms of cervical cancer and using screening opportunities. It seems as if women who lack knowledge would be less inclined to be screened, as Maree and Wright [26] found women who do not know the signs of cancer would not be suspicious of cancer should they experience these signs and delay seeking healthcare which, in the Malawian context, is least affordable.

Our study provided evidence that less than a quarter (22.9%) of the sample had been screened, lacking knowledge of the VIA programme the most commonly reported reason. The low screening percentage concurs with the findings of Hami and others [11], who reported 24.7% of the women in their study had undergone screening. In contrast, our study found the lack of information about the screening programme was the most common reason for not being screened, whilst the study of Hami and colleagues [11] found the most common reasons were not being sick and not having pain, whilst lack of knowledge about cervical cancer screening tests was the least reported. Similarly, Fort and others [27], who conducted a study in the Mulanje District of Malawi, found lack of knowledge as the reason why women are not screened but added low perceived benefits and not regarding screening as a critical healthcare action to the list of reasons for not being screened.

It was interesting to find that a demonstration of the VIA procedure was the most preferred method for being taught about screening followed by posters. Literature focusing on teaching preferences about cancer prevention is limited and except for a South African study conducted by Rwamugira and others [19], no literature could be found. The study of Rwamugira investigated men’s preferences for being taught about cervical cancer, where more than 90% preferred either posters, a pamphlet or a drama. It is noteworthy that the educational level of the men was higher than that of the women in the current study. It seems essential to pilot test demonstration of the VIA procedure as part of educational programmes to determine whether it would indeed motivate women to be screened.

Limitations

Due to the fact that our study was conducted in one rural area, generalisation should be made with great caution. Using a survey design allowed us to investigate relatively superficial knowledge and not a deep understanding of the phenomena under study. In addition, self-report data were collected, which could have led to social desirable and recall bias and guessing. Despite these limitations, we believe the study provided sufficient information to guide the development and implementation of the educational programme aimed at improving of cervical cancer screening utilisation among women living in the study setting.

Conclusion

Our study provided evidence that most of the women had heard of cervical cancer and believed cervical cancer could be cured if detected at an early stage. However, their knowledge of the causes and symptoms of the disease was poor and many did not believe they were at risk for developing cervical cancer. Most of the women had heard of the VIA screening programme, but less than a quarter had ever been screened. A lack of knowledge about this programme was presented as the most common reason for not being screened. Most were willing to be screened if they were reassured that VIA was a simple, painless procedure. Knowing that women would like to have a demonstration of the VIA procedure gives a fresh approach to educational programmes aimed at preventing cervical cancer and it would be interesting to know whether it would enhance cervical screening uptake if implemented.

References

World Health Organization (2015) Cervical cancer: estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/cervix-new.asp. Accessed 31 July 2018

Msyamboza KP, Dzamalala C, Mdokwe C, Kamiza S, Lemerani M, Dzowela T, Kathyola D (2012) Burden of cancer in Malawi; common types, incidence and trends: national population-based cancer registry. BMC Res Notes 5(1):149

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI 85:365–376

Anorlu RI (2008) Cervical cancer: the sub-Saharan African perspective. Reprod Health Matters 16:41–49

Palacio-Mejía LS, Rangel-Gómez G, Hernández-Avila M, Lazcano-Ponce E (2003) Cervical cancer, a disease of poverty: mortality differences between urban and rural areas in Mexico. Salud Pública Mex 45:315–325

Rudd P, Gorman D, Meja S, Mtonga P, Jere Y, Chidothe I, Msusa AT, Bates MJ, Brown E, Masamba L (2017) Cervical cancer in southern Malawi: a prospective analysis of presentation, management, and outcomes. Malawi Med J 29(2):124–129

World Health Organization (2006) Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice. World Health Organization, Geneva

Maseko FC, Chirwa ML, Muula AS (2014) Client satisfaction with cervical cancer screening in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res 14:420

Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention (2004) Planning and implementing cervical cancer prevention and control programs: a manual for managers. Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention, Seattle

Malawi Ministry of Health (2005) National service delivery guidelines for cervical cancer prevention. https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/malawi-hivaids/national-service-delivery-guidelines-cervical-cancer-prevention. Accessed 1 August 2018

Hami MY, Ehlers VJ, Van der Wal DM (2014) Women’s perceived susceptibility to and utilisation of cervical cancer screening services in Malawi. Health SA Gesondheid 19(1)

ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (2017) Malawi. Human papillomavirus and related cancers, fact sheet 2017. http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/MWI_FS.pdf. Accessed 2 August 2018

Kayange P (2005) Fighting against cervical cancer: the case of Malawi. Malawi Med J 17(2):43–44

Kumbani LC, Chirwa E, Malata A, Odland JØ, Bjune G (2012) Do Malawian women critically assess the quality of care? A qualitative study on women’s perceptions of perinatal care at a district hospital in Malawi. Reprod Health 9(30)

Kamanga P, Vedeld P, Sjaastad E (2009) Forest incomes and rural livelihoods in Chiradzulu District, Malawi. Ecol Econ 68:613–624

Ports KA, Reddy DM, Rameshbabu A (2015) Cervical cancer prevention in Malawi: a qualitative study of women’s perspectives. J Health Commun 20:97–104

National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF Macro (2011) Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. NSO and ICF Macro, Maryland

Grove SK, Burns N, Gray J (2014) Understanding nursing research: building an evidence-based practice. Elsevier Health Sciences, Philadelphia

Rwamugira J, Maree JE, Mafutha N (2017) The knowledge of South African men relating to cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening. J Cancer Educ 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1278-4

United Nations (2014) Malawi Country Profile. http://www.mw.one.un.org/country-profile/. Accessed 31 July 2018

World Bank (2018) The World Bank in Malawi. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malawi/overview. Accessed 2 August 2018

Rosser JI, Zakaras JM, Hamisi S, Huchko MJ (2014) Men’s knowledge and attitudes about cervical cancer screening in Kenya. BMC Womens Health 14:138

Mokhele I, Evans D, Schnippel K, Swarts A, Smith J, Firnhaber C (2016) Awareness, perceived risk and practices related to cervical cancer and pap smear screening: a crosssectional study among HIV-positive women attending an urban HIV clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. SAMJ 106:1247–1253

Sheeran P, Orbell S (2000) Using implementation intentions to increase attendance for cervical cancer screening. Health Psychol 19:283–289

Getahun F, Mazengia F, Abuhay M, Birhanu Z (2013) Comprehensive knowledge about cervical cancer is low among women in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Cancer 13:2

Maree JE, Wright SC (2010) How would early detection be possible? An enquiry into cancer related knowledge, understanding and health seeking behaviour of urban black women in Tshwane, South Africa. Eur J Oncol Nurs 14:190–196

Fort VK, Makin MS, Siegler AJ, Ault K, Rochat R (2011) Barriers to cervical cancer screening in Mulanje, Malawi: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 5:125

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maree, J.E., Kampinda-Banda, M. Knowledge and Practices of Cervical Cancer and Its Prevention Among Malawian Women. J Canc Educ 35, 86–92 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1443-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1443-4