Abstract

While it is recognized that cancer treatment can contribute to problems in sexual function, much less is currently known about the specific sexual health concerns and information needs of cancer survivors. This study tested a new instrument to measure cancer survivors’ sexual health concerns and needs for sexual information after cancer treatment. The Information on Sexual Health: Your Needs after Cancer (InSYNC), developed by a multidisciplinary team of experts, is a novel 12-item questionnaire to measure sexual health concerns and information needs of cancer survivors. We tested the measure with a sample of breast and prostate cancer survivors. A convenience sample of 114 cancer survivors (58 breast, 56 prostate) was enrolled. Results of the InSYNC questionnaire showed high levels of sexual concern among cancer survivors. Areas of concern differed by cancer type. Prostate cancer survivors were most concerned about being able to satisfy their partners (57 %) while breast cancer survivors were most concerned with changes in how their bodies worked sexually (46 %). Approximately 35 % of all cancer survivors wanted more information about sexual health. Sexual health concerns and unmet information needs are common among breast and prostate cancer survivors, varying in some aspects by type of cancer. Routine screening for sexual health concerns should be included in comprehensive cancer survivorship care to appropriately address health care needs. The InSYNC questionnaire is one tool that may help clinicians identify concerns facing their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of sexual function as an aspect of cancer survivors’ quality of life after treatment has gained recognition in the research literature during the last decade [1–3]. Some quality of life (QOL) measures developed during this time began to include sexual function domains [1, 2]. The Institute of Medicine now recommends screening and assessment of the survivors’ psychosocial well-being and describes sexual function as an important aspect of survivors’ psychosocial functioning [3]. A growing number of studies have documented the occurrence of sexual dysfunction as a result of cancer and cancer treatment providing a greater understanding about the effect of cancer and its treatment on sexual function [2, 4–7]. However, more information is needed on cancer survivors’ specific concerns about their sexual function, their feelings about themselves as sexual beings, and about their sexual relationships.

To date, several studies have found that survivors are interested in information about sexuality but that their sexual concerns tend to be overlooked by health care providers [8–11]. The providers’ lack of focus on and, in some cases, lack of expertise about survivors’ sexual concerns and information needs make it difficult for survivors to access and benefit from interventions designed to improve their sexual health after cancer treatment. Interventions are emerging that offer ways to improve the recovery of sexual intimacy. These include models for brief couples’ counseling for sexual rehabilitation after localized prostate cancer diagnosis [12, 13] as well as interventions comparing Internet-based counseling to traditional, i.e., face-to-face counseling, for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment [14].

In order to fill this gap in the literature, we designed a brief questionnaire for prostate and breast cancer survivors about their sexual concerns and information needs. We chose breast and prostate cancer survivors because both cancers are common and both groups share similarities with respect to the number of people newly diagnosed each year and the number of long-term survivors (at 5 years, relative survival rate for breast cancer survivors is 90 % and for prostate cancer survivors approaches 100 %) [15]. In addition, treatments for both of these cancers have substantial sexual side effects due in part to their hormone-dependent nature. The primary aim of this study was to test a novel questionnaire in order to (1) identify the sexual concerns of breast and prostate cancer survivors and their needs for information, (2) compare their types of sexual concerns, and (3) determine the relationship between extent of sexual concern and their QOL.

Methods

Instrument Development

The authors, working in collaboration with an interdisciplinary group of content experts from the fields of medicine, nursing, psychology, public health, and social work, developed the Information on Sexual Health: Your Needs after Cancer (InSYNC) questionnaire. This instrument was designed to assess sexual health concerns and information needs after a cancer diagnosis. The questionnaire items were developed after review of the empirical literature addressing sexual health concerns for cancer survivors and their partners. The team of content experts included two certified sex therapy specialists whose focus was the treatment of cancer survivors with sexual problems, and a PhD level oncology nurse with many years of clinical experience. Input was sought from the rest of the team, all of whom were prostate and breast cancer clinicians or investigators. The 12 items were designed to represent the biopsychosocial aspects of sexuality and the most commonly described concerns clinically and in the research, such as how the body will function sexually and reproductively after treatment, confidence in one’s sexual ability with a changed sexual function and an altered body, and the impact of these changes on relationships. (See Fig. 1 for complete list). For each item, the respondents indicated their level of concern on a 5-point Likert scale from “not concerned” to “very concerned.” An additional question for each sexual health concern inquired about their desire for more information (yes/no). After institutional review board (IRB) approval, a pilot study was conducted to evaluate this measure, including time needed to complete the questionnaire, clarity of directions, understanding of questions, discomfort in answering questions, importance of the topic, and recommendations on questions to add or delete. The pilot sample consisted of 10 breast cancer and 16 prostate cancer survivors. Pilot participants indicated that they understood the questions and that none of the questions made them feel uncomfortable. They did not suggest new questions and did not recommend that any questions be deleted. The questionnaire was completed in a relatively short time (average 4 min, range 2–10 min). Following the initial pilot feedback, all 12 items were retained (Fig. 1).

Sample

The study sample consisted of participants age 18 years and older, with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer (stage T1 or T2) or non-metastatic breast cancer (stages 0–III) who were currently receiving or had completed therapy, could read English, and could provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included having a major psychiatric illness, limited life expectancy due to other debilitating medical conditions, metastatic disease, or a previous history of cancer except for squamous or basal cell skin cancer and/or cervical carcinoma in situ. Participants who met eligibility criteria were recruited consecutively by providers in breast and urology clinics. Final screening and recruitment were conducted by member of research team.

Other Measures

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) is a 27-item instrument that measures overall quality of life with subscales on physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well- being [16]. Total scores range from 0 to 108. The measure has been used with cancer survivors and has established reliability and validity [16].

Demographic information obtained included age, gender, self-reported race, education completed, employment status, income level, and partnership status. Date of diagnosis, stage of disease, clinical pathology, treatment type, and date of completion of treatment were obtained from the medical record. As active treatment was thought to continue to impact sexual health, follow-up time was calculated as the time from end of primary treatment to the assessment. Subjects still receiving active treatment were assigned a follow-up time of 0 day.

Procedures

This study was reviewed and approved by the Internal Review Board—Medicine and the University of Michigan Medical School. Potential participants were identified by their providers in the breast and urologic oncology clinics and referred to a member of the research team for final determination of study eligibility. Upon completion of eligibility screening, informed consent was obtained. Participants completed the InSYNC and FACT-G self-administered questionnaires in the clinic setting. A medical history form was completed for each participant by a member of the research team following the visit.

Analysis

Demographic data and time of follow-up differences between breast and prostate cancer survivors were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Each InSYNC item was dichotomized into high (4–5) vs low (1–3) levels of concern to improve reliability given the limited sample size. The levels of concern and information needs for each item were reported for the whole sample with Fisher’s exact test used to determine differences in the levels of concerns by type of cancer. Psychometric testing did not proceed as we considered this a brief screening measure with face validity. Finally, the impact of sexual health concerns on general QOL was assessed, by calculating mean FACT-G scores for the high and low concern groups for each InSYNC item, separately for each type of cancer. Due to the pilot nature of this study, no analyses of the measures took place. All tests were performed using SAS, v9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 131 breast and prostate cancer survivors that were pre-screened and then approached for the study, 115 agreed to participate (response rate 88 %). Fifteen survivors declined participation while one participant withdrew after completing the questionnaire. The study sample consisted of 56 breast cancer survivors and 58 prostate cancer survivors. Breast cancer survivors were younger (median age 52 years vs 64 years, P < 0.001) and were assessed closer to treatment end (5.2 vs. 9.7 months, P = 0.04) than prostate cancer survivors. The majority of participants in both groups were white, married, well-educated, and had a high income, which is consistent with the demographic profile of the study site (Table 1). All participants were assessed within 5 years of their primary cancer treatment end date.

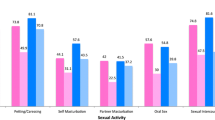

Significant concern levels were common for most items of the InSYNC questionnaire (Table 2), with 10 of the 12 items showing high levels of concern for at least 25 % of the study sample. The items that were most concerning to the study population included changes in how the body works sexually, ability to sexually satisfy their partner, ability to have sexual pleasure, and the effect of their cancer on their overall sexual relationship. Of the two items with lower rates of high concern levels, concerns about the “ability to have children” were likely lower due to the older median age of the study population. Over 80 % of the study population reported being married, which likely alleviated the concerns about “starting a new physically intimate relationship.” Approximately half of the participants with high levels of concern wanted more information on the subject; this level stayed generally consistent across items.

Prostate cancer survivors were significantly more concerned about losing confidence as a sexual partner than breast cancer survivors (p = 0.02, Table 3). There were an additional four items for which the prostate cancer survivors had rates of high concern that were at least 10 % higher than breast cancer survivors (“satisfying partner sexually,” “ability to have sexual pleasure,” “changes in orgasm experience,” and “coping with sexuality changes”). Conversely, breast cancer survivors had rates of high concern that were even 5 % higher than prostate cancer survivors for only two items (“being physically attractive after cancer” and “pain with intercourse”).

A high level of concern was associated with a reduced general QOL for every item for both breast and prostate cancer survivors (Table 4). The effect in prostate cancer survivors was more consistent, ranging from a 0.7- to 5.3-point decline in the mean FACT-G scores. In contrast, six items exceeded a 5.3-point decline in breast cancer survivors, with concerns about “satisfying partner sexually,” “starting a new physically intimate relationship,” and “being physically attractive after cancer” associated with a greater than 8-point difference in the mean FACT-G score. While 39 % of breast cancer survivors were concerned with the “effect on overall sexual relationship,” this concern was associated with only a 0.8-point decline in general QOL.

Overall, there was a bimodal distribution of the number of concerns identified, with both breast and prostate cancer survivors likely to have either no concerns or many (7–10) concerns (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that women and men with a diagnosis of early-stage breast or prostate cancer have similar concerns related to sexual health and functioning. The InSYNC questionnaire appears to be a clinically useful tool for identifying sexual health concerns among cancer survivors. Both breast cancer and prostate cancer survivors had concerns about satisfying their partners sexually and how their bodies work sexually. The additional concerns related to physical changes posttreatment, ability to have sexual pleasure, and concern about the effect on their overall sexual relationship reflect the biopsychosocial nature of sexual health.

The high level of endorsement for both men and women survivors about satisfying a partner sexually suggests the need for further study and intervention. Prostate cancer survivors were mostly concerned about the way their physical changes affect their sexual relationships and their ability to have and give pleasure. These concerns support Messaoudi and colleagues’ [17] finding that erectile dysfunction after prostatectomy leads to lower partner satisfaction and men’s concomitant distress, diminished feeling of masculinity, and anxiety about performance.

Breast cancer survivors reported concerns related to the way their body worked sexually and were concerned about their attractiveness and ability to have sexual pleasure. The highest concerns focused on the physical changes, attractiveness, ability to have sexual pleasure, and pain with intercourse. Since over a third of the women in this study reported concern about their physical attractiveness, body image may be a significant contributor to women’s concerns about satisfying their partners. Our findings are consistent with the report by Scott and Kayser who in their review of interventions in sexual health for women with gynecological cancers (2009) found that interventions that address body image along with other health concerns are more effective [18]. It also supports studies of the general population that indicate that appearance is a part of the way in which a woman judges her sexual performance with a male partner [19–22].

The InSYNC questionnaire findings also suggest that when men and women have sexual concerns, they also would like more information about the how to manage those concerns. Providers should include questions about sexual concerns during routine visits and provide information or referral sources that can address those concerns.

It is important to note the finding that women who had lower FACT-G scores were more concerned than women with higher FACT-G scores about satisfying a partner sexually, starting a new intimate relationship, and being physically attractive. These women may be more concerned about their ability to establish and maintain a successful sexual relationship. It is also possible that women who indicate lower quality of life on the FACT-G may have more fatigue and less energy to engage in sexual relationships. Since there was no difference in women’s sexual concerns by age (median age 52), it appears that women of all ages have concerns related to sexual health and partner sexual satisfaction.

This study has several strengths. The identification and comparison of sexual concerns and information needs of individual cancer survivor groups are areas that have been largely neglected in survivorship care, and this study begins to address this gap in the literature. While sexual concerns and information needs have been identified in breast and prostate cancer survivors, this study provides a model for assessment in cancer survivors with other diagnoses. Additionally, this study contributed to the further development of a novel instrument, the InSYNC questionnaire, that identifies sexual health concerns and need for sexual health information in cancer survivors. The InSYNC questionnaire is a practical measure that could be used in a busy clinic to identify cancer survivors in need of additional counseling and information. The format of this measure could be easily adapted from pencil-and-paper to an electronic format that could be used to assess sexual health concerns and information needs between clinic visits.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size collected at a single institution, lack of diversity in relationship status, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation, and a single time point for data collection. This may affect generalizability. Future work in sexual health concerns of cancer survivors should include studies with large and more diverse samples. We believe the InSYNC questionnaire could be used with survivors of cancers other than prostate and breast cancer. Larger studies would allow for stratification of participants by length of time as a survivor and would help clinicians understand more about the natural history of sexual concerns in cancer survivors. Based on understanding cancer survivors’ sexual concerns and information needs, interventions tailored by concern could be developed and evaluated. Sexual health is an important and legitimate part of survivors’ expression and self-care.

References

Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG (2000) Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 56(6):899–905

Wilmoth MC, Tingle LR (2001) Development and psychometric testing of the Wilmoth Sexual Behaviors Questionnaire-Female. Can J Nurs Res 32(4):135–151

Adler NE, Page AEL (eds) (2008) Institute of medicine: cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. The National Academies Press, Washington

Hughes M (2008) Alternations of sexual function in women with cancer. Semin Onc Nurs 24:91–101

Hollenbeck BK et al (2004) Sexual health recovery after prostatectomy, external radiation, or brachytherapy for early stage prostate cancer. Curr Urol Rep 5:212–219

Incrocci L (2005) Changes in sexual function after treatment of male cancer. J Mens Health Gend 2:236–243

Gomella L (2007) Contemporary use of hormonal therapy in prostate cancer: managing complications and addressing quality-of-life issues. BJU Int 99(Suppl):25–29

Baker F et al. (2005) Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer 104(Suppl. 11):2565–76

Hordern AJ, Street AF (2007) Communicating about survivor sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust 186:224–227

Hill EK et al. (2011) Assessing gynecological and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer 15:2643–2651

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E (2012) Changes to sexual well-being and intimacy after breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 35(6):456–65

Canada A, Nesse L, Sui D, Schover L (2005) Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 104(12):2690–2700

Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T (2011) Intimacy-enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: a pilot study. J Sex Med 8(4):1197–1209

Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, Sui D, Neese L, Jenkins R, Rhodes MM (2011) A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. doi:10.1002/cncr.26308

American Cancer Society (2012) Cancer treatment and survivorship facts & Figs. 2012–2013. American Cancer Society, Atlanta

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G et al (1993) The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11:570–579

Messaoudi R et al (2011) Erectile dysfunction and sexual health after radical prostatectomy: impact of sexual motivation. Int J Impot Res March 23(2):81–86

Scott JL, Kayser K (2009) A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women’s sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J 15(1):48–56

Pujols Y, Meston CM, Seal BN (2009) The association between sexual satisfaction and body image in women. J Sex Med 7:905–916

Dove NL, Wiederman MW (2000) Cognitive distraction and women’s sexual functioning. J Sex Mar Ther 26:67–78

Seal BN, Meston CM (2007) The impact of body awareness on sexual arousal in women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 4:990–1000

Meana M, Nunnink SE (2006) Gender differences in the content of cognitive distraction during sex. J Sex Res 43(1):59–67

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Matthias Kirch, MS, for editorial assistance.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge use of the services and facilities of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Michigan.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crowley, S.A., Foley, S.M., Wittmann, D. et al. Sexual Health Concerns Among Cancer Survivors: Testing a Novel Information-Need Measure Among Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients. J Canc Educ 31, 588–594 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0865-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0865-5