Abstract

Introduction

People who trade sex face violence and discrimination across individual, community, and systemic levels. The goal of the current study is to examine the impact of the terms used for people who trade sex (e.g., sex worker, prostitute, individual who sells sex, whore, escort) on people’s perceptions of individuals who trade sex within the United States.

Methods

The current study used a prototype methodology to understand the impact of these terms. Data were collected in 2022 and participants were asked to provide 5 characteristics of each term describing a person who trades sex and designate these characteristics as positive, negative, or neutral.

Results

Participants attributed more negative than positive characteristics to people who trade sex, broadly. When describing a Prostitute, an Individual who Sells Sex (ISS), and a whore, participants reported markedly more negative characteristics than when describing a Sex Worker or an Escort.

Conclusion

Greater attention to the language used to describe people who trade sex is needed.

Policy Implications

At present, the term prostitute and/or prostitution is used consistently in legal statutes and literature. Given the markedly negative perceptions associated with these terms, reforming social and legal policies utilizing this and other stigmatizing terms is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

People who trade sex continue to face increased rates of violence and discrimination across the USA (Chan, 2021). Scholars have theorized that systemic societal, political, and interpersonal challenges faced by this population are at least in part due to pervasive stigma and dehumanization of people who trade sex (Lazarus et al., 2012). Dehumanization, which is the process of depriving someone of the positive aspects of a human being, has been historically perpetuated through societal policies, laws, and language (Haslam, 2021). Though many labels and terms have been historically used to identify people who trade sex, little is known about the impact of these terms on the perception of this population and the resulting level of stigma/discrimination towards them. The current study aims to examine perceptions of people who trade sex through the varying terms used to identify them.

Defining Sex Trade

Sex trade occurs across a continuum of agency-to-victimization that encompasses sex work, commercial sexual exploitation, and sex trafficking (Gerassi & Nichols, 2017). Diverse pathways bring people into sex trade whether as adults trading sex voluntarily (i.e., in the presence of alternatives) and/or as independent workers (Kurtz et al., 2005; Lazarus et al., 2012). People may also trade sex in order to meet their basic needs or in a context of constrained choices (Benoit et al., 2019; McCarthy et al., 2014); through exploitation of preexisting vulnerabilities (e.g., addiction, intellectual disability, citizenship status, and homelessness); or through force, fraud, or coercion (Trafficking Victims Protection Act, 2020). Sex trade can take place in many settings (e.g., indoors, outdoors, online) and in many forms (e.g., commercial sex, erotic webcamming, pornography).

Stigmatizing Attitudes Towards People who Trade Sex

Stigma is the assignment of an inferior status to individuals and groups on the basis of a social attribute that distinguishes them from others and is often tied to the attitudes and beliefs one has about a person or a group of people (Goffman, 1963). Stigmatizing attitudes play a driving role in the discrimination people who trade sex face across individual, community, and systemic levels (Nadal et al., 2014). These attitudes have been shown to affect this population’s ability to adequately access and receive necessary healthcare services (Cohan et al., 2006; Lazarus et al., 2012), access quality, affirming mental health services (Koken, 2012; Pederson et al., 2019), maintain custody and supervision over children (McClelland & Newell, 2016), avoid employment and housing discrimination (Nadal et al., 2014), and receive fair and unbiased treatment in the court and criminal justice system (PROS Network & Sex Workers Project, 2012). Incidents of harassment, discrimination, and physical or sexual violence are often under reported to law enforcement due to the legitimate fear of being dismissed, stigmatized, and/or harassed by the police (Lyons et al., 2017; Stenersen et al., 2022). Ultimately, these factors result in and perpetuate a collective stigma and dehumanization of people who trade sex in the USA.

At an inter- and intrapersonal level, stigma impacts individuals’ self-concept and social interactions as they may experience exclusion, judgment, and shame (Benoit et al., 2018; Wolf, 2019). Benoit and colleagues write that people who trade sex experience high levels of stigma because they are aware that they may be “seen as ‘symbolically dirty’… stereotyped as irresponsible, criminal or vectors of disease and are treated as a threat to self or public” (Benoit et al., 2019, p. 2). Literature regarding the opinion of the public toward this population further emphasizes this point, noting that the public often holds attitudes towards people who trade sex as a nuisance, inferior, and immoral (Nadal et al., 2014; Stenersen et al., 2020). As this stigma remains pervasive in society, people who trade sex are left exposed to public shame, social estrangement, state monitoring, and police harassment (Grittner & Walsh, 2020). Grittner and Walsh (2020) tie this back to stigma, writing that “many sex workers identify stigma as intertwined with pervasive beliefs that sex workers are personally to blame or deserve the violence and discrimination they experience” (p. 1673).

People may also internalize stigmatizing attitudes, expect rejection, and navigate challenging choices related to concealing or disclosing trading sex (Bloomquist & Sprankle, 2019). Koken (2012) qualitatively explored how sex workers’ (N = 30) perceived sex work stigma and what strategies they used to manage the impact of stigma on their lives. Many of the women Koken (2012) interviewed anticipated rejection from family and friends if they disclosed sex work. As such, they opted to cope by concealing their involvement in sex work rather than face potential blame, shame, and judgement (Koken, 2012). However, coping with stigma by relying primarily on concealment was often linked to increased social isolation and decreased social support. These findings illustrate how stigma functions to perpetuate the exploitation, control, or exclusion of people (Link & Phelan, 2014).

Finally, the choice to resist and manage stigma is one that is constantly navigated by people who trade sex (Grittner & Walsh, 2020; Morrison & Whitehead, 2005; Weitzer, 2018). In their 2018 article, Weitzer outlines the comprehensive stigma faced by sex workers in addition to laying out actions and efforts needed to decrease and ultimately eliminate this stigma. In doing so, this article also highlights the need to understand and implement non-stigmatizing language when referring to sex workers and their associates (e.g. client, worker, provider, manager; Weitzer, 2018).

Language

Language is central to the expression and maintenance of prejudiced beliefs, stigmatizing attitudes, and resulting dehumanization (Burgers & Beukeboom, 2020; Collins & Clément, 2012; Ng, 2007). Language, as a facet of communicative interaction, creates and recreates reality through shared agreements that reflect and reinforce broader cultural, social, and political contexts (Riley & Wiggins, 2019). The current study’s focus on the influence of labels is informed by previous research illustrating how different labels (i.e., derogatory vs. non-derogatory labels) used to refer to members of the same stigmatized group have distinct connotations and cue vastly different perceptions of that group (Carnaghi & Maass, 2007; Collins & Clément, 2012). This is important given the known influences attitudes and perceptions of groups can have on subsequent behavior (Glasman & Albarracin, 2006; Jain, 2014). In this way, the terms used to describe people who trade sex matter, especially in the contexts of healthcare, social services, education, research, policy, and advocacy.

In addition, research has shown language to be critical to how historically stigmatized groups perceive their place in society. For example, Matsick and colleagues (2022) extended previous work exploring the impact of labels on people’s perceptions of sexual minorities to focus on the specific impact of linguistic heterosexism on those being labeled (i.e., lesbian and gay people). The authors found that people in this stigmatized group attended to the labels others used to describe them and utilized this choice of label to draw conclusions about how others perceived them, with particular attention to the ways in which labels may communicate cues related to threat or safety (Matsick et al., 2022). These findings align with literature noting the impact of stigmatizing interpersonal experiences on people who trade sex (Benoit et al., 2019; Pederson et al., 2019).

When examining studies regarding attitudes towards and experiences of people who trade sex, terms used to identify this group vary widely and include terms such as prostitute (Boache et al., 2021), sex worker (Ma & Loke, 2020), people who exchange sex (Kislovskiy et al., 2022), and individual who sells sex (Stenersen & Ovrebo, 2020). Further, many studies have emphasized attitudes towards prostitution and the act or legal status of selling sex rather than towards the individual who engages in sex trade (Ma et al., 2018). Though previous studies use different language when describing this population, little is known about how the use of these terms may have influenced the attitudes captured by these studies.

The Current Study

Despite knowing the immense impact of stigma on the lives of people who trade sex, no known research has examined the impact of specific terms when exploring perceptions and stigma. Indeed, the language used to describe people who trade sex within societal and legal context has often been inconsistent and a source of conflict among scholars, policy makers, advocates, and people with lived experience in the sex trade. It is important to explore the impact of these terms on the public’s perception of people in the sex trade. The current study aims to accomplish this goal using a prototype methodology to examine perceptions of people who trade sex based on varying identifying terms. This information can be used to inform future policy, research, and intervention strategies regarding this population by helping us to understand the impact and implications of the words we choose to use when we discuss people who trade sex.

Method

Procedure

The current study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Memphis prior to recruitment and data collection. All participants completed an online survey through the Qualtrics survey platform. Just under half of all final included participants (n = 27) were recruited using online means including posting a link and information regarding the survey to online social media sites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) as well as blog sites (e.g., Reddit). Participants recruited through these methods participated in the survey voluntarily without compensation. The remaining participants (n = 33) were recruited and participated in the survey through Amazon MTurk. Amazon MTurk participants were compensated $0.25 for their time.

Participants

Participants in the current study included a total of 60 adults currently residing in the USA. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 70 years old with a mean age of 36.72 years old and a median age of 33. A majority of participants identified their race as White (n = 40, 66.7%) followed by Asian/Asian American (n = 10, 16.7%), Black/African American (n = 7, 11.7%), Latinx/Hispanic (n = 5, 8.3%), and South Asian (n = 1, 1.7%). Of note, participants were able to identify all races that they identified with so racial identification is not mutually exclusive. Regarding gender, the majority of participants identified their gender as cisgender woman (n = 30, 50%) followed by cisgender man (n = 24, 40%), non-binary (n = 3, 5%), transgender man (n = 1, 1.7%) and other, not specified (n = 1, 1.7%). When asked to self-identify (i.e. write in) the specific terms participants used to describe their gender, the most frequently endorsed responses included woman (n = 26, 43.3%), man (n = 21, 35%), and cisgender (n = 21, 35%). Two participants reported using the terms non-binary (n = 2, 3.3%) and/or Two Spirit (n = 2, 3.3%). The terms agender, gender non-conforming, transgender, transmasculine, and femboy all received one response each (1.7%).

Participants were also asked about their engagement in either purchasing sex and/or sexual services and trading sex and/or sexual services. A majority of participants reported that they had never purchased sex or sexual services during their lifetimes (n = 52, 86.7%). A total of four participants reported having engaged in sex trade either currently (n = 2, 3.3%) or previously but not currently (n = 2, 3.3%).

Instrument

The current study utilized demographic and prototype data. Consistent with prototype methodology (Martz et al., 2009; McCaughey & Strohmer, 2005; Stenersen et al., 2020), participants were asked to “list at least 5 words and/or phrases that define and describe a…” each of the five terms used to refer to people who trade sex (i.e., prostitute, sex worker, individual who sells sex, whore, escort). As they were entering their words and/or phrases, participants were asked to designate each word/phrase as either positive, negative, or neutral. Each participant was presented with these instructions for all five terms; however, the terms were presented to participants in random order. For example, one participant may be asked to describe first the term prostitute, followed by whore, escort, individual who sells sex, and sex worker. A second participant would be presented with these same words but in a different order. Participants were asked to provide at least five words and/or phrases but were given space to provide up to six words and/or phrases for each term. Finally, it should be noted that the basis for this study was to understand how these prototypes are created, what they consist of, and how they shape perceptions of people who trade sex. Though the authors recognize and appreciate the vast heterogeneity in services the sex trade, to ensure the collection of genuine prototypic characteristics, participants were intentionally given no leading stimuli regarding the type of sex trade.

Subjectivity and Trustworthiness

The four people making up the research team of the current study each have unique backgrounds and experiences with this study’s content area. The research team is diverse in their career stage, professional role, clinical experience, gender identity, and race. At the time of writing, one author is a professor, one is a second-year postdoctoral fellow, and two are late-stage doctoral students. All authors have a disciplinary background in counseling psychology and conduct research with, and/or have engaged in advocacy, and/or clinical work with individuals involved in the sex trade and/or have worked in sex work. Given our shared clinical focus, it is likely that in the process of analysis, the research team was especially attentive to issues of clinical importance. Further, our shared social justice, anti-oppression, liberation-oriented values have resulted in taking great care and intentionality within data creation, data analysis, and dissemination of results. Since biases and subjectivity are inevitable components of all research endeavors (Schweber, 2006), we approach the current study with the intent to cultivate research trustworthiness.

In qualitative research, trustworthiness (see Lincoln & Guba, 1985) can be accomplished through attending to a study’s degree of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. In addition to coming to consensus in pairs, the authors came to consensus about all aspects of data coding, interpretation, and theme building to establish credibility. Further, our results build on existing research and scholarship, thus corroborating our findings and conclusions. To ensure transferability, we have been intentional about anchoring our results in broader systems of power to richly describe how current social, cultural, and political structures reflect and reinforce discourses about people who trade sex. Confirmability has been demonstrated by critically and rigorously examining the extent to which our assumptions and biases have impacted the entire research process, thus adding richness and sincerity to our audit trail. Finally, peer review and future additional research and replication will aid in ensuring our study is dependable.

Data Analysis

Immediately following data collection, data were cleaned and organized by completing the following steps: (1) giving each participant a unique identifier, (2) removing any participants who did not provide any prototype responses and (3) removing any responses that consisted of “don’t know,” “not applicable,” or likewise. Following data cleaning, analysis was conducted consistent with extant literature using prototype methodology (Martz et al., 2009; McCaughey & Strohmer, 2005; Stenersen et al., 2020). Specifically, each term provided to participants (i.e., prostitute, whore, ISS, escort, sex worker) was analyzed independently to construct a prototype of that term according to participant responses. Of the four study authors, two authors analyzed two of the terms (escort, sex worker), and the remaining two authors analyzed the remaining three terms (ISS, prostitute, whore). Analysis began by each author independently examining all the words and/or phrases given by participants to describe each term. From there, each author independently sorted each word and/or phrases into categories representative of characteristics of a person. For example, one would not have a category named “education” but may have a category named “educated.” Each author was encouraged to first crudely sort the characteristics into categories then modify and shift characteristics and categories until they were satisfied that all categories were mutually exclusive.

Once each rater was satisfied with their list of categories and the words/phrases included in them, they met with the author analyzing the same term with the goal of coming to consensus on the list of categories for each term and the words/phrases included in these categories. Once each pair had determined their category list the entire team of authors met to discuss their categories, resolve any remaining conflicts, and come to consensus on the wording of categories that occurred in more than one term. This process took place over the course of multiple meetings totaling approximately 12 hours of analysis and discussion. In total, 1535 responses from the 60 participants were analyzed with 879 meeting criteria for inclusion in the final categories. Responses were excluded from the final categories if they exclusively consisted of a term used to describe a person who trades sex (e.g., “sex worker,” “prostitute”).

Finally, after final categories and superordinate categories were determined, frequency level of each category and superordinate category was determined as outlined by McCaughey and Strohmer (2005) and based on the number of participants who noted words and/or phrases in each category and superordinate category. A core frequency level indicated that over 50% of all participants reported a word/phrase included in the category/superordinate category. Secondary frequency level included a category/superordinate category reported by 29–49% of participants and a tertiary frequency level reported by 20–28% of participants.

Results

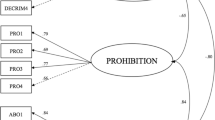

Results revealed a total of 17 categories of participant responses regarding their perceptions of each of the terms give to describe people who trade sex. Seven of these categories were designated by participants as positive or neutral (positive/neutral) and fell within superordinate categories of behavioral (professional) or personal (physically attractive, confident, independent, sex positive, classy, private). The remaining 10 categories were designated at negative or neutral (negative/neutral) and fell within superordinate categories of behavioral (substance use, sexually promiscuous), situational (exploited, marginalized, poor, in need of help), or personal (sad, disgusting, desperate, bad). Full categories and frequency levels for each term are outlined in Table 1. Terms that reached meaningful frequency are described in greater detail below. Consistent with prototype methodology, the n figures noted in the results refer to the number of participants who noted characteristics in each category.

Behavioral

The superordinate category of behavioral represents categories of characteristics regarding behaviors or actions of people who trade sex. Positive/neutral behavioral characteristics were mentioned most frequently for the term escort and least frequently for the terms prostitute, sex worker, and whore. Negative/neutral behavioral characteristics were mentioned most frequently for the term prostitute followed by sex worker, whore, escort, and least frequently for the term individual who sells sex.

The behavioral superordinate category contains one category designated as positive/neutral (professional) and two categories designated as negative/neutral (substance using, sexually promiscuous). The positive/neutral category of professional was mentioned at a secondary frequency for the term escort and tertiary frequency for individual who sells sex. Professional did not reach a meaningful frequency for any other terms. Negative behavioral characteristics were mentioned across all terms at either a tertiary (individual who sells sex, sex worker, whore, escort) or secondary (Prostitute) frequency level. This superordinate category is made up of two categories including substance use and sexually promiscuous. The category of substance use did not reach a meaningful frequency level for any of the terms provided.

Professional (Positive/Neutral)

Positive behavioral characteristics were made up by a single category of professional. This category included terms such as “professional”, “running a business”, and “business” and was most frequently reported by participants when asked to describe an escort. When referring to escort, the term professional was mentioned by 37% of participants (n = 22). The next most frequent term described as professional was individual who sells sex, for which this category was mentioned by 25% of participants (n = 15). The frequency of professional for all other terms (prostitute, whore, escort) did not reach a meaningful frequency level.

Sexually Promiscuous (Negative/Neutral)

The category of sexually promiscuous included references to an individual who was frequently and indiscriminately sexually active and included responses such as “easy”, “promiscuous”, and “flirt”. This category was meaningful across all terms and was most frequently mentioned when participants were asked to describe a prostitute (n = 33). Specifically, over 50% (n = 33) of participants mentioned a characteristic within this category. Sex worker (n = 25), whore (n = 24), and escort (n = 20) were described within the category of sexually promiscuous at a secondary level and individual who sells sex (n = 17) at a tertiary level.

Personal

The personal superordinate category represents categories that note characteristics related to one’s personal physical appearance, personality, or personhood. As outlined in Table 1, both positive/neutral and negative/neutral personal characteristics are mentioned at a meaningful frequency for all terms. Of note, positive/neutral personal characteristics were mentioned most frequently for the term escort and least frequently for the term whore. Conversely, negative/neutral personal characteristics were mentioned most frequently for prostitute, individual who sells sex, and whore and least frequently for escort and sex worker.

This superordinate category is made up of 10 categories total, 6 positive/neutral (physically attractive, confident, independent, sex positive, classy, private) and 4 negative/neutral (sad, disgusting, desperate, bad). A total of 8 categories (4 positive/neutral: confident, independent, sex positive, and private; 2 negative/neutral: sad, desperate) did not reach a meaningful frequency level. Further, the remaining two positive/neutral categories (physically attractive, classy) reached meaningful frequency for the term escort only.

Physically Attractive (Positive/Neutral)

Physically attractive includes characteristics referencing the attractive physical attributes of an individual and included characteristics such as “sexy”, “pretty”, and “beautiful.” This category reached a meaningful frequency level only for the term escort where it was mentioned by a total of 16 participants, leading to a tertiary frequency level.

Classy (Positive/Neutral)

The category classy included reference to personal characteristics of an individual regarding a high level of societal class. Characteristics in this category were noted exclusively when prompted to think of an escort and included responses such as “classy”, “high end”, “upscale”, and “luxurious.” Characteristics in the classy category were mentioned by 26 participants referring to the term escort, reaching a secondary frequency level.

Disgusting (Negative/Neutral)

The category of disgusting included responses referring to characteristics of an individual that were either physically undesirable (e.g., “filthy”, “gross”) or personally undesirable (e.g., “trashy”, “waste”) and reached a meaningful frequency level for all terms except sex worker and escort. In particular, characteristics in the disgusting category were mentioned most frequently for the term whore (n = 25) followed by prostitute (n = 19) both of which reached a secondary frequency level among participants. Finally, 12 participants noted characteristics in this category for the term Individual who sells sex.

Bad (Negative/Neutral)

The negative/neutral category of bad reached a meaningful frequency level only for the term whore which was mentioned at a secondary frequency level. Bad included personal characteristics of an individual who has a bad influence on others and/or society. This included reference to individuals as “evil”, “bitch”, “rude”, and “manipulative.”

Situational

Finally, the superordinate category of situational is made up of entirely negative/neutral categories that reference characteristics of an individual’s situation and/or context. Characteristics in this superordinate category were mentioned most frequently for the term prostitutes at a core level (n = 37), followed by sex worker (n = 27), whore (n = 24), and individual who sells sex (n = 18) at a secondary level. Finally, situational characteristics were mentioned for escort at a tertiary frequency level (n = 13). Of the four categories in this superordinate category (exploited, marginalized, poor, in need of help), only one (exploited) reached a meaningful frequency level for any of the terms.

Exploited (Negative/Neutral)

The category of exploited included responses referencing an individual who is under the influence of another. Specifically, characteristics reported in the exploited category included “coerced”, “trafficked”, “controlled”, and “used.” Responses in this category were reported most frequently for the term prostitute (n = 16) followed by the term whore (n = 9) both at a tertiary frequency level.

Discussion

The current study aimed to understand the perceptions underlying common terms used to refer to people who trade sex. Underlying this aim is the potential for language routinely used in both societal and legal contexts to influence the level of stigma, discrimination, and violence experienced by people who trade sex in the USA. Given the alarming rate of discrimination and violence enacted toward people who trade sex (Deering et al., 2014; Stenersen et al., 2022; Stotzer, 2009), the critical examination of language use is essential to promoting effective discrimination and violence prevention measures at individual, community, and systemic levels.

Results of the current study allow readers to not only visualize how our participants perceive people who trade sex, but also to compare and contrast how participants’ perception of people who trade sex vary greatly depending on the term chosen to describe them. Several patterns of results clearly emerged from this analysis and comparison that are valuable to informing future choice of the terms in social, legal, and policy settings. First, participants reported markedly more negative characteristics when asked to describe a prostitute, an individual who sells sex (ISS), and a whore than when describing a sex worker or an escort. In particular, over half of our participants associated negative personal characteristics (e.g., sad, disgusting, desperate, bad) with a prostitute, an ISS, and a whore. Though still frequent at a secondary level, fewer participants attributed negative personal characteristics when describing a sex worker and an escort. Relatedly, the term escort received the most mentions of positive personal characteristics, at least double the frequency compared to all other terms. The categories of classy and private were exclusively mentioned when participants were describing an escort. Taken together, these results point to a perception of people who use the terms sex workers and escorts as more personally attractive, whereas terms like prostitutes, ISS, and whores are conversely seen personally in a negative light. Yet, because language reflects and reinforces social, cultural, and political humanization or dehumanization of people, these results point to perceptions of people who trade sex as being much more consequential than the seemingly benign opinions about attractiveness or acceptability might indicate.

As the term prostitute and/or prostitution is currently utilized most consistently in legal statutes and frequently in academic literature concerning people who trade sex, the view of this term has particular implications for policy and societal structure. Broadly speaking, when describing a prostitute, participants attributed more negative behavioral, personal, and situational characteristics. Compared to all other terms, prostitute received the most characteristics mentioned referring to a prostitute as sexually promiscuous and exploited. Participants noted almost three times the amount of negative situational characteristics (e.g., exploited, marginalized, poor) and twice as many negative personal characteristics (e.g., disgusting bad, desperate) when describing a prostitute compared to escort. These perceptions and the prevalence of this term in criminal justice and legal policy have clear implications for the ability of people who trade sex to access equitable, and respectful societal services (e.g., healthcare, law enforcement; Lazarus et al., 2012). Additionally, though it is certainly not only the language of these policies that is necessary to reduce stigma and violence, language used colludes with the social and cultural dehumanization of this population, increasing their risk of discrimination and violence.

While participants primarily used negative terms when describing people who trade sex, the positive characteristics they attributed must also be addressed. Indeed, more accurate narratives about sex trade will not focus exclusively on the risks and challenges, but also that which is gained through sex trade (e.g., flexibility, independence, community, access to basic needs, pleasure). Broadly, participants used positive terms more frequently when describing an escort or an ISS. The theme of professionalism is reflective of the discourse around sex trade as a valid occupation that requires significant skill, emotional labor, and hard work (Antebi-Gruszka et al., 2019; Pederson et al., 2019). Further, sex trade may be framed in career or vocational terms, centering the role of labor rights for people who trade sex. The theme of independence also emerged as a positive characteristic within the data. This reflects narratives related to pathways into sex trade as well as factors that keep people in sex trade. For example, sex trade can be a means for accessing wants or needs both inside and outside the context of constrained choices (e.g., when facing job discrimination; Nichols, 2016). Within qualitative interviews, sex workers have also described how sex trade can provide the independences of being one’s own boss and having autonomy to make one’s own schedule, which can be particularly useful for people who have caregiving responsibilities, are managing chronic illness or disabilities, or are pursuing education/creative pursuits (Pederson et al., 2019). Participants also used a number of positively designated words to physically describe people who trade sex (e.g., sexy, pretty, beautiful). Future research should explore the meaning embedded in such terms and the way factors such as racism, colorism, and anti-fat bias relate to perceptions of people who trade sex (e.g., degree of dehumanization, perceptions of agency vs. victimization). Overall, the positively designated characteristics our participants shared allowed us to unearth both the inkling of shifts in narratives around sex trade that can continue to be explored and uplifted.

Finally, the results of the current study further exemplify the broader recognition of oppression of people who trade sex in the USA by study participants. Specifically, though unknown to authors prior to final review, several negative result categories integrate neatly into the five faces of oppression framework first introduced by Young (2009). Young proposed oppression as the accumulation of five elements including exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence. The current study’s categories of exploited and marginalized represent the first two of these elements with in need of help and desperate speaking to the element of powerlessness. Regardless of term, this theme of oppression against people who trade sex was known and voiced by participants. Further, the results of the current study appear to demonstrate a relative dissonance between the recognition of people who trade sex as an oppressed group, while also overwhelmingly attributing negativity to this group personally.

Implications

The current results have implications for multiple sectors of society including research, social policy, clinical practice, and broader societal discourse. First, despite the broad array of terms used in different contexts to refer to people who trade sex, little to no research has examined the impact of language on the broader experience of this population. Future research would benefit from expansion of the current results and examination of the context in which this language is used to inform societal policies. Continuing to use language that perpetuates stigmatizing and dehumanizing views such as those expressed by many of our participants may contribute to a context where people who trade sex are viewed as personally responsible for the violence and discrimination the experience (Grittner & Walsh, 2020). Placing blame on individuals can distract from the role of social-, legal-, and policy-level processes in perpetuating harm towards people who trade sex. On a legal and policy level, we must also acknowledge that the criminalization of people who trade sex has an incredible impact in perpetuating this stigma and dehumanization. The language used in these contexts (largely prostitute/prostitution) only serves to further cement this dehumanization. Though changes in language and terms remain critical, and have the potential to assist in the prevention of oppression and violence against people who trade sex, there must also remain focus and action on the larger conversation of criminalization and the great impact of the policies themselves on the lives of people who trade sex.

In clinical spaces, preliminary research has shown that language in the context of mental health treatment can impact a client’s willingness to initiate, engage, and attend services (Grittner & Walsh, 2020; Pederson et al., 2019; Wolf, 2019). In a 2019 study involving the wants and needs of sex workers in mental health treatment, Pederson and colleagues found that sex workers voiced a need for therapists to, among other things, mirror their clients’ own language when referring to their work and use judgement-free language when talking about sex trade. To avoid clinician’s own preconceptions and assumptions about people who trade sex, like the ones reported in the current study, engaging in critical self-reflection regarding biases and taking a firm client-centered approach to language could be quite beneficial (Antebi-Gruszka et al., 2019; Bloomquist & Sprankle, 2019; Wolf, 2019). This is especially true because the results of the current study provide a clear indication of terms that perpetuate the stigmatization and dehumanization of people who trade sex and should be avoided. Thus, learning and using the language people with lived experience use to describe themselves is a vital step towards humanization and could help move away from the detrimental effects of self-stigmatization.

Finally, the results of the current study have the potential to bolster the community-based literature including white pages and fact sheets put out by sex work advocacy organizations across the USA (National Sex Workers Project, n.d.; Bloomquist & Sprankle, 2017). For example, a 2017 study by the Sex Workers Outreach Project found that, among their undergraduate sample, vignettes of a sexual assault survivor using various sex worker terms (e.g., sex worker, prostituted woman, prostitute) received significantly less victim empathy and more victim blame compared to the non-sex worker terms (e.g., social worker, woman). Somewhat contrast to the current study, however, researchers found no significant difference in victim empathy based on the term used within the sex worker terms (Bloomquist & Sprankle, 2017). Ultimately, as collective dehumanization of people who trade sex in the USA remains pervasive, the use of humanizing language is a small but critical step towards ensuring the safety, equity, and respect people who trade sex deserve.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is not without limitations. First, while relatively large compared to similar qualitative studies, the current study’s results reflect the responses of 60 adults. Given this, the generalizability of the current findings to the broader public of the USA should be considered with caution. Second, though participants responses were valuable in constructing a prototype of each term, the prototype methodology did not allow for the examination of perceptions based on other demographic characteristics (e.g., race, ethnicity, age, gender identity, history of sex trade). Given the disproportionate rates of discrimination and violence experienced by people of color and trans people who trade sex, future studies should consider expanding on current results to examine whether and how the perceptions of this population differ based on these minoritized identities. Future research may also benefit from increased understanding of the preference and prototype of people involved in sex trade regarding identifying terms. Third, though participants were presented with each term in a random order and were able to return to their previous responses, it is possible that the order in which they were presented with the prototype terms could have influenced their attitudes towards subsequent terms. Finally, the current study’s sample was taken from across the USA. Future research may benefit from the examination of these perceptions and their consequences within smaller geographic areas. For example, the examination of perceptions and rates of violence in a city that uses the term prostitute in policy language compared to another location that may use a different term.

Conclusion

This prototype study aimed to uncover the impact of the different terms for people who trade sex on perceptions of individuals who trade sex within the USA. Our results highlight the often stigmatizing and dehumanizing ways in which people who trade sex are viewed. Such perspectives are important to understand given their role in reflecting current societal perspectives and perpetuating violence and discrimination against people who trade sex. Important differences emerged in the degree of negative characteristics attributed to people who trade sex based on the specific terms used, which point to concrete implications for practice and policy. In practice, our results contribute to a body of literature emphasizing the importance of medical, mental health, and other social service providers challenging their biases towards people who trade sex taking a client-centered approach in practice. Similarly, legal and legislative realms ought to consider how social and cultural anti-sex worker violence is enacted and invited through language use. In law, policy, and literature, we recommend not only moving away from using the term prostitute and/or prostitution, but also examining institutional contributions to dehumanization of people who trade sex given the markedly negative perceptions associated with this term.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Antebi-Gruszka, N., Spence, D., & Jendrzejewski, S. (2019). Guidelines for mental health practice with clients who engage in sex work. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 34(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2019.1573978

Benoit, C., Jansson, S. M., Smith, M., & Flagg, J. (2018). Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 457–471.

Benoit, C., Smith, M., Jansson, M., Magnus, S., Maurice, R., Flagg, J., & Reist, D. (2019). Canadian sex workers weigh the costs and benefits of disclosing their occupational status to health providers. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 16(3), 329–341.

Bloomquist, K., & Sprankle, E. (2017). The effects of language & identity of sex work on stigma & the sex workers’ rights movement. Retrieved from https://swopusa.org/blog/2017/09/19/research-summary-the-effects-of-language-identity-of-sex-work-on-stigma-the-sex-workers-rights-movement/

Bloomquist, K., & Sprankle, E. (2019). Sex worker affirmative therapy: Conceptualization and case study. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 34(3), 392–408.

Boache, H., Delgado, N., Pina, A., & Hernandez-Cabrera, J. A. (2021). Prostitution policies and attitudes towards prostitutes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 1991–2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01891-9

Burgers, C., & Beukeboom, C. J. (2020). How language contributes to stereotype formation: Combined effects of label types and negation use in behavior descriptions. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39(4), 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0261927X20933320

Carnaghi, A., & Maass, A. (2007). In-group and out-group perspectives in the use of derogatory group labels: Gay versus fag. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(2), 142–156.

Chan, H. C. (2021). Sex worker homicides and sexual homicides: A comparative study of offender, victim, and offense characteristics. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 39(4), 402–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2528

Cohan, D., Lutnick, A., Davidson, P., Cloniger, C., Herlyn, A., Breyer, J., ... & Klausner, J. (2006). Sex worker health: San Francisco style. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(5), 418–422.

Collins, K. A., & Clément, R. (2012). Language and prejudice: Direct and moderated effects. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 31(4), 376–396.

Deering, K. N., Amin, A., Shoveller, J., Nesbitt, A., Garcia-Moreno, C., Duff, P., ... & Shannon, K. (2014). A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. American Journal of Public Health, 104(5), e42–e54. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301909

Gerassi, L. B., & Nichols, A. J. (2017). Sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Prevention, advocacy, and trauma-informed practice. Springer Publishing Company.

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster.

Grittner, A. L., & Walsh, C. A. (2020). The role of social stigma in the lives of female-identified sex workers: A scoping review. Sexuality & Culture, 1–30.

Haslam, N. (2021). The social psychology of dehumanization. In M. Kronfeldner (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429492464

Jain, V. (2014). 3D model of attitude. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 3(3), 1–12.

Kislovskiy, Y., Erpenbeck, S., Martina, J., Judkins, C., Miller, E. & Chang, J. C. (2022). HIV awareness, pre-exposure prophilaxis perceptions and experiences among people who exchange sex: Qualitative and community partnered participatory study. BMC Public Health. Under Review. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1374001/v1

Koken, J. A. (2012). Independent female escort’s strategies for coping with sex work related stigma. Sexuality & Culture, 16(3), 209–229.

Kurtz, S. P., Surratt, H. L., Kiley, M. C., & Inciardi, J. A. (2005). Barriers to health and social services for street-based sex workers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16(2), 345–361.

Lazarus, L., Deering, K. N., Nabess, R., Gibson, K., Tyndall, M. W., & Shannon, K. (2012). Occupational stigma as a primary barrier to health care for street-based sex workers in Canada. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(2), 139–150.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (2014). Stigma Power. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 24–32.

Lyons, T., Krüsi, A., Pierre, L., Kerr, T., Small, W., & Shannon, K. (2017). Negotiating violence in the context of transphobia and criminalization: The experiences of trans sex workers in Vancouver. Canada. Qualitative Health Research, 27(2), 182–190.

Ma, H., & Loke, A. Y. (2020). Knowledge of, attitudes towards, and willingness to care for sex workers: Differences between general and mental health nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 36(4), 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.01.002

Ma, P. H. X., Chan, Z. C. Y., & Loke, A. Y. (2018). A systematic review of the attitudes of different stakeholders towards prostitution and their implications. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15, 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0294-9

Martz, E., Strohmer, D., Fitzgerald, D., Daniel, S., & Arm, J. (2009). Disability prototypes in the United States and the Russian Federation: An international comparison. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 53(1), 16–26.

Matsick, J. L., Kruk, M., Palmer, L., Layland, E., & Salomaa, A. (2022). Extending the social category label effect to stigmatized groups: Lesbian and gay people’s reactions to “homosexual” as a label. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 10(1), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.6823

McCarthy, B., Benoit, C., & Jansson, M. (2014). Sex work: A comparative study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(7), 1379–1390.

McCaughey, T. J., & Strohmer, D. C. (2005). Prototypes as an indirect measure of attitudes toward disability groups. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 48(2), 89–99.

McClelland, G. M., & Newell, R. (2016). A qualitative study of the street-based prostitution. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13, 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987108095409

Morison, T. G., & Whitehead, B. W. (2005). Strategies of stigma resistance among Canadian gay-identified sex workers. In J. T. Parson (Ed.), Contemporary Research on Sex Work (pp. 169–179). Routledge.

Nadal, K. L., Davidoff, K. C., & Fujii-Doe, W. (2014). Transgender women and the sex work industry: Roots in systemic, institutional, and interpersonal discrimination. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 169–183.

National Sex Workers Project. (n.d.). Resources. Retrieved June 26, 2023, from https://www.nswp.org/resources

Ng, S. H. (2007). Language-based discrimination: Blatant and subtle forms. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(2), 106–122.

Nichols, A. J. (2016). Sex trafficking in the United States: Theory, research, policy, and practice. Columbia University Press.

Pederson, A., Stenersen, M. & Bridges, S. (2019). Towards affirming therapy: What sex workers want and need from mental health providers. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0022167819867767

PROS Network and Sex Workers Project. (2012). Public health crisis: The impact of using condoms as evidence in New York City. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://swp.urbanjustice.org/news-room/resources/

Riley, S., & Wiggins, S. A. L. L. Y. (2019). Discourse analysis. In M. Forrester (Ed.) Doing qualitative research in psychology: A practical guide. (pp. 233–256) Sage Publications.

Schweber, S. S. (2006). Insights into Big Science. Metascience, 15(1), 167–171.

Stenersen, M., & Ovrebo, E. (2020). The development and validation of the attitudes towards individuals who sell sex inventory (ATISS). Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30, 843–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1758272

Stenersen, M., Thomas, K. & McKee, S. (2022). Police and transgender and gender diverse people in the United States: A brief note on interaction, harassment, and violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F08862605211072161

Stenersen, M. R., Ovrebo, E., Adams, K. L., & Hayes, L. R. (2020). Foreigners’ attitudes toward individuals who sell sex in Thailand: A prototype study. International Perspectives in Psychology, 9(2), 131–144.

Stotzer, R. L. (2009). Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(3), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.006

Trafficking Victims Protection Act. (2020). 22 U.S.C. § 7101–7110.

Weitzer, R. (2018). Resistance to sex work stigma. Sexualities, 2(5–6), 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460716684509

Wolf, A. (2019). Stigma in the sex trades. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 34(3), 290–308.

Young, I. M. (2009). Five faces of oppression. In G. L. Henderson & M. Waterstone (Eds.), Geographic thought: A praxis perspective (pp. 55–71). Routledge.

Funding

The first author’s contribution was partially funded by NIH grant T32DA019426.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The current study involved human participants and was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Memphis. Each participant was provided with and consented to an informed consent document outlining the procedures of the study as approved by the aforementioned institutional review board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosure

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stenersen, M., Pederson, A.C., Domínguez, S. et al. “Please Describe a Person who Sells Sex”: (De)humanizing Prototypic Perceptions in the USA. Sex Res Soc Policy 21, 493–502 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00845-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00845-9