Abstract

Introduction

Attitudes toward non-normative families, such as those composed of LGBTQ parents and stepparents, have improved over the last few decades. However, prejudice has not disappeared, but has only mutated into modern forms. This experimental study aimed to investigate the conditional mechanisms explaining negative attitudes toward non-normative mothers. We predicted that when evaluating conflicts within a family, a heterosexual biological mother would be viewed as being less responsible for her children’s misbehavior than non-normative mothers, and these attributions would, in turn, impact on perceptions of competence and morality as a manifestation of modern prejudice for those with highly heteronormative beliefs.

Methods

Four hundred and two Italian heterosexual and cisgender participants from the general public took part in a questionnaire from November to December 2022. Each participant read one of four different vignettes describing a conflict between two children and their mother. Specifically, a target mother’s sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. lesbian mother) and her biological connectedness to children (biological mother vs. stepmother) were manipulated. Then, the participants responded to measures on mothers’ competence, morality, and responsibility for the children’s misbehavior, and scales on gender role beliefs and sexual prejudice.

Results

Results of moderated mediation showed that the familial conflict provided a rationalization according to which people with high levels of gender role beliefs—or sexual prejudice—attributed more responsibility and less competence—or less morality—to non-normative mothers compared with heterosexual biological mothers.

Conclusions

This study found that non-normative mothers are stigmatized on competence or moral bases eliciting attributions for conflict with their children.

Policy Implications

These results contribute to the growing number of studies exploring attitudes toward non-normative family arrangements and are relevant for clinicians and policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent research shows that people’s attitudes toward “non-normative” families, such as those composed of LGBTQ parents and stepparents, have improved over the last few decades (Kranz, 2022; Saint-Jacques et al., 2020). Furthermore, scholars have found that children in LGBTQ families and stepfamilies positively evaluate the quality of relationship with their parents (Clarke & Demetriou, 2016; Jensen & Howard, 2015). For instance, adult children of LGBTQ parents clearly reject the attribution of being “damaged” by their parents’ sexual orientation or parents’ gender identity, even when reporting some difficulties experienced in heterosexist cultures (Clarke & Demetriou, 2016). Furthermore, in stepfamilies in which the stepparent concluded the process of adoption, stepchildren report high-quality perception in stepparent–stepchildren relationships (Jensen & Howard, 2015). However, these positive results do not represent the evidence that prejudice has disappeared.

In many Western societies, as a result of new social norms and legislation, discrimination has become less tolerable and prejudice has mutated into subtle and modern forms that are sometimes difficult to detect (Dovidio, 2001; Morrison & Morrison, 2011; Morrison et al., 2009). For instance, LGBTQ persons can still be the target of subtle forms of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination through micro-aggressions, denial of contact, or denial of discrimination (ILGA, 2023; Massey et al., 2013; Salvati et al., 2020). Also, same-sex parents are still targets of stigma and high scrutiny in terms of their competence and capacity to offer a nurturing environment for their children (e.g., Ballone et al., 2023; Di Battista et al., 2020a, 2020b; Leal et al., 2021; Pacilli et al., 2017). This is true for gay men who stereotypically are assumed to have a marginal interest in fatherhood (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Ioverno et al., 2018), as well as for lesbian women who tend not to be linked with the traits generally associated with mothers, such as being self-sacrificing or nurturing (Hequembourg & Farrell, 1999; Salvati et al., 2018). Stepfamilies, potentially including both same-sex parents and different-sex parents, continue to be stigmatized compared to the nuclear family (Ganong & Coleman, 2018), being considered as an incomplete institution (Coleman et al., 1997), or a deviant family form with a high risk of being conflictual and less stable than intact families are (Claxton-Oldfield & O'Neil, 2007; Planitz & Feeney, 2009). Recent reviews (Goldberg, 2022) have further revealed that LGBTQ people continue to face stigma and invisibility in becoming parents, especially when they represent multiple marginalized statuses, such as in the case of lesbian or gay stepparents.

Perceptions of Non-normative Parents’ Competence

In many studies on prejudice, by using a vignette approach depicting a parent having a conflict with their children or partner, participants were asked to rate same-sex parental competence (Di Battista et al., 2020a; Kranz, 2022; Massey et al., 2013; McLeod et al., 1999; Štrbić et al., 2019; Tušl et al., 2020), or stepparents’ competence (Claxton-Oldfield, 1992; Di Battista, 2023; Di Battista et al., 2022, 2023). These studies did not find that parents were directly judged negatively on competence and skills as expected. On the contrary, prejudice toward stepparents or same-sex parents was found to arise only in certain situations, particularly those with a negative connotation that were also attributed to parents, provided with a subtle or socially acceptable way to do so (e.g., Claxton-Oldfield, 1992; Di Battista et al., 2020a; Moreno & Bodenhausen, 2001). For instance, Ballone et al. (2023) found that a predictor of negative attitudes toward gay fathers’ competence was the attribution of higher conflicts for gay parental couples than for a different-sex couple. Other studies similarly found that perceptions of lesbian mothers’ and stepmothers’ competence were lower than for heterosexual biological mothers through the mediation of attributions of mothers’ responsibility for a conflict with children (e.g., Di Battista et al., 2022, 2023). In other words, past research showed that a conflict between mothers and children was used by people with high levels of gender role beliefs to attribute responsibility to “non-traditional” mothers and, in turn, this attribution predicted judgments of low competence for these targets. This strategic interpretation of a conflict or a negative situation within the family was confirmed in other studies (Massey, 2007; Massey et al., 2013). Massey and colleagues (2013) found that participants with high levels of modern homonegativity rated negative behaviors of a parent in a same-sex couple more negatively than the same behaviors of a heterosexual parent; however, this effect did not emerge in a positive vignette scenario. Massey (2007) explained these results as a negative causal attribution for out-group members representing a subtle channel with which to express sexual prejudice. In other words, the fact that a child displayed misbehaviors or conflicts with parents allows the prejudice to manifest itself via a negative attribution to parents from people with high levels of modern homonegativity.

Moral Stigmatization and Motherhood

Authentic and essential motherhood has been predominately viewed as biological, mono-maternal, and positioned within a hetero-patriarchal family and, in this sense, motherhood has been expected to meet the high moral standards of intensive mothering (Park, 2013). The bulk of research has consistently shown that few evaluative dimensions drive judgment toward others (Brambilla & Leach, 2014 for a review). Starting from the classical distinction between warmth and competence, researchers ascertained that morality—a subdimension of the original warmth—represents the most important antecedent of judgment processes (Leach et al., 2007; see also Ellemers et al., 2013). Furthermore, there is evidence that both evaluations of motherhood and attitudes toward same-sex parents are strongly moralized (see Rhee et al., 2019 for a review). However, moral stigmatization of non-normative mothers is an underexplored field of research and to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored the relationship between attribution of responsibility and moral stigmatization of lesbian (step)mothers.Footnote 1

LGBTQ people can be perceived as immoral especially by religious and politically conservative groups (Costa et al., 2014; Ioverno et al., 2018). A morality framework in which media and politics promote the traditional family model is typically presented by those opposing all forms of non-traditional family (Clarke, 2001; Lingiardi et al., 2016). Judgments of immoral behaviors are indeed one of the most common arguments against gay men and lesbian women parents (Clarke, 2001; Costa et al., 2014). However, research is not clear on the processes through which some beliefs become moralized for certain groups of parents. Some scholars (Pacilli et al., 2011; van der Toorn et al., 2020) have argued that strongly believing that social roles are naturally divided for gender and heterosexuality is a given rather than one of the possible identities (“view of what is”) may predict attitudes concerning what is normative or, on the contrary, immoral (“view of what should be”) through processes of system justification. In other words, the fact that social roles are mostly divided along a binary gender line and that children are conceived “naturally” through sexual intercourses of different-sex persons is something which is viewed as a natural order to respect. Furthermore, following Massey (2007), a familial conflict can represent further negative evidence that same-sex parents do not respect this natural order and that they are culpable and, ultimately, less moral than heterosexual parents.

In the literature, the judgment of mothers’ morality seems to be more qualified by their non-normative sexual orientation than by their missing biological bond with their children as in the case of stepmothers (Valiquette-Tessier et al., 2016). In general, stepparents tend to receive many negative attributions related to competence, conflict management, and maladaptation (Planitz & Feeney, 2009; Saint-Jacques et al., 2020), and lesbian stepmothers tend to be rated as being not very stable and secure (Claxton-Oldfield & O’Neil, 2007). However, judgments pertaining to morality do not seem specific for stepmothers. For instance, investigating the contents of stereotypes attributed to different typologies of mothers, Ganong and Coleman (1995) found that stepmothers were judged as having poor family relationships, being incompetent in raising children, lacking many positive personal characteristics (e.g., being patient, caring), and possessing several undesirable personal attributes (e.g., being unkind, unreasonable). However, the level of attribution of immorality was extremely low and lower compared with the same attribution for the targets “women in general” and “never married mothers.”

This study aimed, on the one hand, to confirm previous findings concerning perceptions of competence (e.g., Di Battista et al., 2022, 2023), exploring attitudes toward mothers with multiple marginalized or invisible statuses. On the other hand, this study aimed to extend the previous investigations, exploring the impact of negative attributions of responsibility on perceptions of mothers’ morality.

The Current Study

In Italy, there is no specific distinction between stepparent adoption and second-parent adoption, but a unique form of adoption in “particular cases” that regulates, among others, the adoption of the biological child of one of the partners in a couple. This kind of adoption is defined “adoption for particular cases” or “non legitimizing adoption” (1983, Law no. 184). This kind of adoption does not fit with the same discipline of full adoption because a permanent state of the adoptive child’s abandonment is not declared. It includes two conditions that need to be recognized: the biological parents’ consent must be obtained and the adoption must satisfy the child’s best interests (Montanari Vergallo, 2019). This adoption does not sever the original family bonds and is not automatic but arranged by the Italian Minors Court only after careful screening of partner prerequisites such as emotional suitability, competence, and personal and economic situation (Montanari Vergallo, 2019).

Italian lawmakers have made a distinction between marriage for different-sex couples and civil union for same-sex couples, also in terms of parenthood rights. In this sense, civil union legislation does not allow, in principle, an adoption of any kind for same-sex couples. However, since 2007, the Courts of Milan and Florence have extended the “adoption for particular cases” to same-sex couples. In 2014, Rome Tribunal affirmed that parental competence is independent from sexual orientation of the adopting adults, and in 2016, the Italian Constitutional Court has recognized the “adoption for particular cases” for same-sex couples implementing the sentence passed by the Tribunal of Rome. However, in the Italian system, judges are bound by the law and judicial decisions are not a source of law. Therefore, the role of the courts is limited to just applying the right norm to the dispute, interpreting it if necessary. For its part, the Italian parliament continued to regulate adoptions only for married different-sex couples, since only this model is assumed to offer the necessary stability in parental relationships (Montanari Vergallo, 2019).

However, in the Italian context, it has become common for two women, a stepmother and a biological one, to raise children from previous different-sex relationships or donor-insemination abroad (Montanari Vergallo, 2019). Considering that the “adoption for particular cases” is not automatic and that, in the case of same-sex parents, municipal registrars had sometimes refused to register a child born abroad, claiming it would be contrary to public order, the recognition and protection of non-normative families seem to be highly influenced by “the degree of open-mindedness and on the conscience of each judicial panel” (Montanari Vergallo, 2019, p. 15). Based on these premises, it is still important to consider the biases that may influence perceptions toward non-normative parents.

This study investigated perceptions of normative and non-normative mothers’ competence and morality in the Italian context presenting a vignette scenario in which two children had a conflict with their—heterosexual or lesbian—biological mother or adoptive stepmother (Di Battista et al., 2022). Heterosexual biological mothers were supposed to be perceived as being more competent and less responsible for their children’s misbehavior compared to lesbian (step)mothers and heterosexual stepmothers due to a stereotypical view of family roles. However, following previous study results (e.g., Di Battista et al., 2022, 2023), it was not predicted the lesbian stepmothers would be doubly stigmatized due to both their sexual orientation and biological disconnectedness with their children.

Furthermore, this study intended to explore perceptions of mothers’ morality predicting a moral stigmatization of lesbian (step)mothers (i.e., lesbian stepmothers and biological lesbian mothers) due to their sexual orientation.

More specifically, it was predicted that when evaluating an identical conflict within a family, a heterosexual biological mother would be viewed as being less responsible than non-normative mothers, and these attributions would, in turn, impact on perceptions of competence as a manifestation of modern prejudice for those with high gender role beliefs (Ballone et al., 2023; Di Battista et al., 2022; Massey et al., 2013). Also, the same conflict scenario could provide a similar rationalization by which people with high levels of sexual prejudice would attribute more responsibility and less morality to lesbian (step)mothers compared with heterosexual (step)mothers, regardless of biological connectedness with their children (see Fig. 1). Therefore, based on the rationale described above, we expected:

For participants with high levels of gender role beliefs, heterosexual biological mothers would be judged as being more competent than all non-traditional mothers (i.e., heterosexual stepmothers and lesbian (step)mothers) through the mediation of attribution of responsibility for a mother-children conflict (H1).

For participants with high levels of sexual prejudice, heterosexual (step)mothers would be judged as being more moral than lesbian (step)mothers through the mediation of attribution of responsibility for a mother-children conflict (H2).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Four hundred and thirteen people participated in a self-reported questionnaire from November to December 2022. However, 3 people were not Italian and 8 failed the manipulation check questions. Inclusion criterion was “To be older than 18 years old.” We did not indicate specific exclusion criteria. However, we considered important not to include in the analysis those who had failed the attention control questions and foreign participants who could have had difficulty understanding the language of the questionnaire. The remaining participants were N = 402 heterosexual and cisgender people with Italian nationality from the general public (283 female participants; 70.4%; M age = 38.85, SD = 15.61, from 18 to 78). Almost half of the participants self-identified as biological parents (44.3%; n = 178), 5 participants were adoptive parents (1.2%), and n = 116 were childfree participants (53.7%; 3 were missing concerning this information).

A self-report questionnaire was administered electronically via the Qualtrics platform. The study was presented to participants as a survey collecting perceptions toward different forms of motherhood. Potential participants were recruited by using a convenience sample strategy and were notified that the study was completely anonymous and that they could skip any of the question(s) they did not wish to answer. Only then did they give their consent to participate. After filling out the socio-demographic section, each participant was randomly assigned to one of four vignettes to prevent any survey ordering effects (Vignettes from Di Battista et al., 2022).

The research complied with the WMA Declaration of Helsinki (1964/2013). Approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board for Research in Psychology, University of Verona (Italy; protocol code: 159372).

Materials and Measures

Socio-Demographic Section

Participants’ age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, parenting status, and nationality were collected.

The Vignettes

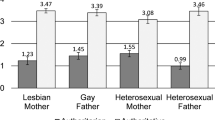

In four different vignettes (Di Battista et al., 2022) depicting some episodes of mild conflict between 5-year-old twins and their mother, the mother’s pathway to parenthood (i.e., biological mother vs. non-biological adoptive mother of the biological partner’s children) and sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual mother vs. lesbian mother) were manipulated. Specifically, in the vignettes, four different families were presented in which the active parent was always the mother: (1) a biological heterosexual mother (n = 99); (2) a biological stepmother (n = 96); (3) a lesbian stepmother (n = 105); (4) a biological lesbian mother (n = 102). In all the scenarios, a negative mother-children interaction was presented. In general, at the end of a day of school, two 5-year-old twins were misbehaving, crying, and wanting their mother to buy toys and sweets for them. Their mother, who engaged with her children, was frustrated and lost her temper. Each participant read only one version of the vignettes and then, they responded to three manipulation and attention-checking items (e.g., “Antonio and Sara are the biological children of Anna;” responses: 1 = true; 2 = false).

Morality

Three bipolar adjectives measuring parenting traits of the target mother (from Weed & Nicholson, 2015) were assessed at opposite poles of a 6-point scale. The items measured a subscale in which higher scores corresponded to a more moral/honest perception of the depicted mother’s behavior: immoral/moral, promiscuous/faithful, delinquent/law-abiding. A total score was computed on the grounds of the mean (α = 0.91, M = 4.23, SD = 1.14; skewness = − 0.28, kurtosis = − 0.56).

Competence

Three ad hoc items were administered in order to measure the perception of the target mother’s competence (from Di Battista et al., 2022): competence, preparation, and capacity as a mother on a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = absolutely disagree; to 6 = absolutely agree). Higher scores indicated a better perception of the mother’s competence. A total score was computed on the grounds of the mean (α = 0.93, M = 4.10, SD = 1.21; skewness = − 0.35, kurtosis = − 0.38).

Attribution of Responsibility

Participants also attributed the depicted children’s misbehavior to the mother described in the vignette on a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree; to 6 = strongly agree; 9 items; e.g., “Antonio and Sara are misbehaving because Anna doesn't act as a good mother;” from Di Battista et al., 2022). Higher scores corresponded to higher participants’ attribution of the mother-children conflict to a perceived inappropriate mothering role. A total score was computed on the grounds of the mean (α = 0.87, M = 2.31, SD = 0.95, skewness = 1.12, kurtosis = 1.27).

Gender Role Beliefs

The 8-item subscale “Gender Linked” of the Social Roles Questionnaire (e.g., “Mothers should work only if necessary;” Baber & Tucker, 2006) assessed participants’ attitudes toward gender roles on a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree; to 6 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicated more stereotypical attitudes toward gender roles. Items were added (α = 0.83, M = 18.54, SD = 8.11, skewness = 0.93, kurtosis = 0.13).

Sexual Prejudice

The 7-item subscale “Modern Heterosexism” of the Multidimensional Scale of Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men (e.g., “I believe same-sex parents are as capable of being good parents as heterosexual parents;” Reversed item; Gato et al., 2012; the Italian validation in Scierri & Batini, 2019) measured sexual prejudice on a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = absolutely disagree; to 6 = absolutely agree). An index of sexual prejudice was created on the grounds of the mean (α = 0.86, M = 2.95, SD = 1.31, skewness = 1.12, kurtosis = − 0.63).

Data Analyses

Statistical preliminary analyses such as reliability analyses, descriptive statistics, and correlations were conducted. The values for asymmetry and kurtosis were acceptable, with few exceptions slightly exceeding |1|. The sample size was established by means of two distinct power analyses—one related to the interaction hypothesis and the other to the mediation hypothesis. With one tested predictor (i.e., the interaction) on a total of three (i.e., two main effects and interaction), the power analysis for moderated regression yielded a required sample size of 395 (f2 = 0.02, 1-β = 0.80, α = 0.05). Power analysis for mediation was estimated taking as the reference sample size the one emerging from the interaction power analysis (see Pellegrini et al., 2021). We opted for a conservative parameter in terms of effect size and number of replications. Specifically, we set low expected correlations (i.e., 0.20) among predictor, mediator, and criterion. As suggested by Schoeman et al. (2017), we set values of 5000 and 20,000 for the total number of power analysis replications and the number of coefficients draws per replication, respectively. Analysis revealed a statistical power of 0.90 associated with the sample size of 395 observations.

The hypotheses were tested performing moderated mediation analyses in which the effects of the mother’s conditions on the evaluation of competence—and morality—through the mediation of the attribution of responsibility depended on levels of participants’ gender role beliefs—and sexual prejudice. To test these models, we used the SPSS PROCESS macro for testing moderated mediation (model 7; Hayes, 2013). Attitudes toward the mother’s competence or morality were modelled as dependent variables (Y), while gender role beliefs or sexual prejudice were modelled as moderators (W). The attribution of responsibility was modelled as mediator (M) and the vignette scenario was the categorical independent variable (X).

Results

Table 1 shows correlations among variables.

As can be observed in the correlation matrix, regardless of the mother’s sexual orientation or the pathway to parenthood, attribution of responsibility was negatively related to perceptions of competence and morality and, on the contrary, positively related to gender role beliefs and sexual prejudice.

Competence Perceptions

Following the first hypothesis, a model tested the effects of the four types of mothers on the perception of competence through the mediation of the attribution of responsibility moderated by the levels of participants’ gender role beliefs. Results showed that the equations for both the effects on the attribution of responsibility, R2 = 0.34, F (7, 394) = 29.33, p < 0.001, and competence, R2 = 0.30, F (4, 397) = 42.18, p < 0.001, were significant. Furthermore, the interaction between the independent variable and gender role beliefs significantly impacted on the attribution of responsibility, ΔR2 = 0.06, F (3, 394) = 11.31, p < 0.001. In line with H1, the indexes of moderated mediation for the difference between the heterosexual biological mother and the heterosexual stepmother (X1) or the lesbian stepmother (X2) were significant indicating that the conditional indirect effects were defined by the levels of gender role beliefs (see Table 2). Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation for the difference between the heterosexual biological mother and the lesbian biological mother (X3) was significant.

Moral Stigmatization

Following the second prediction, a model tested the effect of sexual orientation (i.e., − 1 = heterosexual (step)mothers or 1 = lesbian (step)mothers) on the perception of morality through the mediation of the attribution of responsibility moderated by the levels of participants’ sexual prejudice. Equations for both the effects on attribution of responsibility, R2 = 0.23, F (3, 390) = 38.16, p < 0.001, and morality, R2 = 0.23, F (2, 391) = 59.58, p < 0.001, were significant. The interaction between the independent variable and sexual prejudice significantly impacted on the attribution of responsibility, ΔR2 = 0.04, F (1, 390) = 18.5, p < 0.001. The index of moderated mediation indicated conditional indirect effects that was defined by different levels of sexual prejudice (see Table 3).

Discussion

Recent research examining societal prejudice toward non-normative families compared to heterosexual and nuclear families did not reveal the expected differences (Kranz, 2022). However, prejudice was sometimes found to arise in experimental studies using the vignette approach (Ballone, 2023; Di Battista, 2022) in which participants were provided with a subtle or socially acceptable way to express prejudice, such as to evaluate a possible—dispositional—attribution to parents for a negative familial situation.

In the present study, as for perception of mothers’ competence, participants endorsing medium and high levels of stereotypical gender role beliefs judged the depicted heterosexual or lesbian stepmothers to be less competent compared to the heterosexual biological mothers by attributing them more responsibility for the depicted conflict with their children. Furthermore, participants holding medium and high levels of stereotypical gender role beliefs perceived the lesbian biological mother as being less competent compared to the heterosexual biological mothers by attributing her more responsibility for the same familial conflict. Therefore, moderated mediation analyses evaluating predictors of non-normative mothers’ competence perceptions confirmed previous similar studies’ results (Di Battista et al., 2022, 2023). Specifically, when evaluating identical conflicts within a family, the non-normative mothers were viewed as being more responsible for the conflict, and these attributions, in turn, predicted perceptions of competence as an expression of modern prejudice for those with high levels of heteronormative beliefs (Ballone et al., 2023; Di Battista et al., 2022; Massey et al., 2013). In other words and in line with the literature (Massey et al., 2013), a vignette scenario in which a familial conflict between mother and children arises was the means by which people expressed their prejudice toward "non-traditional" forms of motherhood. These results are also in line with the gendered ideology of the intensive mothering mandate (Hays, 1996), and heteronormative beliefs endorsing that biological and heterosexual mothers are the most appropriate parent (DiLapi, 1989; Valiquette-Tessier et al., 2016).

Concerning moral stigmatization, results showed that at high levels of sexual prejudice, the lesbian (step)mothers were perceived as being less moral compared to the heterosexual (step)mothers by attributing them responsibility for the familial conflict. Again, the scenario of a conflict provided a rationalization by which people with high levels of sexual prejudice attributed more responsibility and less morality to lesbian (step)mothers compared with heterosexual (step)mothers. These results are in line with studies showing that negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians include perceptions of moral contamination and moral impurity (Dasgupta et al., 2009; Vezzali et al., 2017). For instance, Koleva and colleagues (2012) demonstrated strong and negative associations between moral foundations and attitudes about same-sex marriage and relations, over and above political ideology, age, gender, and religious attendance.

However, participants with low levels of gender role beliefs or low levels of sexual prejudice perceived the normative mother as being less moral and less competent as compared with the non-normative mothers by attributing them responsibility for the family conflict. As a tentative interpretation, to verify in future studies, these results could be a reflection of a discriminatory context, within which people with low prejudices and low gender stereotypes try to adjust their responses and contrast the victimization of minority groups. This is in line with studies finding that LGBTQ allies are strongly aware of the risks of victimization that LGBTQ parents and family members face in a highly stigmatizing context (Duncan et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2014). Indeed, non-normative families are still targets of thorough scrutiny and judgments from the scientific community and political stakeholders as well as from lay people in general and they are expected to exhibit hyper-appropriate and “perfect” behaviors to avoid discrimination (Ballone et al., 2023; Clarke & Demetriou, 2016; Lingiardi & Carone, 2016).

Clinical and Social Policy Implications

These findings are interesting for both clinicians and policy implications. On the one hand, clinicians working with different types of families could gain valuable insights from these findings about how prejudice impacts on non-normative parents, their children, and people who relate to these families at various levels. Subtle forms of prejudice, microaggressions, and social rejection can still have a negative impact on both stepfamilies and families with same-sex parents (Massey et al., 2013; Morrison & Morrison, 2011). The ways in which people try to counter heteronormativity and sexual prejudice may not always be functional. For example, in interviews with children from LGBTQ families, Clarke and Demetriou (2016) found the children’s understandable desire to feel as normal and valued as possible while simultaneously defending their parents from social judgments. As a result of stigmatizing contexts, these children’s narratives tended to downplay differences with other heterosexual and cisgender parents’ families and place any possible difficulties in the broader social context. However, it was not clear if these children still had a chance to express possible familial conflicts that were independent from the sexual orientation and gender identity of parents, and if they could express their own family queer differences and pride.

At the policy level, these findings can help to reflect on the difficulties of stepmothers, whether lesbian or heterosexual, whose pathways to parenting are different from those of heterosexual parents who have access to full adoption in Italy. Furthermore, our results confirm that prejudice toward non-normative parents is still present in the Italian context and may be manifested in subtle forms. The changing role of women in Italian society, the recognition of divorce, unmarried couples, and their children have led to a new notion of family in the last decades (Montanari Vergallo 2019). However, perceptions of motherhood continue to be strictly traditional with several implications in the expectations of parental roles (Di Battista, 2023). The negative attitudes toward non-normative mothers’ competence as well as the perceived lower morality of lesbian (step)mothers can make the path toward recognition and protection of non-normative mothers and families difficult. In 2019, the Italian Constitutional Court (n. 221) stated that there was no fundamental right to parenthood for same-sex couples, and in January 2023, the Italian government ordered that municipalities stop the registration of children with same-sex parents, leaving these children in limbo. As a result, in April 2023, Italy was condemned by the EU parliament for anti-rights, anti-gender, and anti-LGBTIQ rhetoric.

In general, understanding that prejudice can manifest itself at an overt level or an implicit level through attributions of responsibility for conflicts that may arise regularly in any family can help to understand the importance of spreading a culture of inclusion and respect. This insight might be used when dealing with training sessions as well as when approaching intervention strategies seeking to reduce prejudice and discrimination against non-normative parents.

We are convinced that socio-psychological research might offer a relevant contribution in limiting the negative effects of stereotypes and prejudice against same-sex and stepparents, and it can be useful to develop interventions aimed at promoting scientific knowledge and inclusion among both the scientific and the general public. As already mentioned, stereotypes and prejudices against these family typologies persist in Italy (Baiocco et al., 2015); therefore, we believe that educational programs should be structured to deconstruct stereotypes regarding non-normative families. We hope that our work will help to offer some useful insights for this goal.

Limitations and Future Directions

The sample is unbalanced with respect to gender and age since it mainly includes young women. Many studies have suggested that these variables could have a role in prejudice since women (Gubernskaya, 2010; Kinlaw et al., 2015; Lingiardi et al., 2016), younger people, and those having a diversified family context have a less conservative view of the family (Kinlaw et al., 2015). These variables were not part of the hypotheses of this study. Entered as covariates in order to test whether they had an effect on the results of this study or, if they modified the observed effects, they did not produce significant results. However, future studies should replicate the moderated mediation models in more representative samples. Among the limitations, it should be also considered that the directionality of the associations between the variables cannot be determined because of the cross-sectional design. Administering a social desirability scale could also help test its effect on the expression of prejudice. Furthermore, the dimensions of competence and morality are highly correlated in the observed results. The fact that they are kept as separate dimensions in this study is a choice based on the hypotheses and the literature, which shows that we can refer to two distinct dimensions of social perception and judgment (Leach et al., 2007; see also Ellemers et al., 2013). In future studies, the two dimensions could be appropriately manipulated to observe interaction effects with parental sexual orientation. A further research direction might deepen and extend the investigations of people’s perceptions of competence and morality of parents and/or stepparents with other sexual and gender identities (i.e., trans* or gender variant parents), and might investigate the LGBTQ people’s perceptions of competence and morality of different scenarios. On the one hand, this would allow us to extend the generalizability of our results. On the other hand, the inclusion of scenarios with parents and/or stepparents with other sexual and gender identities or the inclusion of LGBTQ participants would allow a broader and more inclusive understanding of these processes, lending a voice to individuals who risk remaining invisible even in research on LGBTQ issues (Salvati & Koc, 2022).

Conclusions

This study found support for the prediction that non-normative forms of motherhood, such as those in which mothers have a non-heterosexual orientation or care for their partners’ children, could be stigmatized on competence or moral bases eliciting internal attributions for a conflict with their children. Even if egalitarian ideals may lead individuals to avoid being influenced by their negative beliefs toward minorities, negative attitudes toward non-normative forms of parenting are still present and were found when participants were provided with some apparently legitimate bases for negative evaluations.

Availability of Data and Material

Data will be provided by the corresponding author under reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

We used the term “stepmothers” to indicate all mothers who were non-biological mothers, independently from their sexual orientation. We used the term “lesbian (step)mothers” in all the cases in which we referred to lesbian mothers, both biological ones (i.e., lesbian mothers) and step ones (i.e., lesbian stepmothers). Similarly, we used the term “heterosexual (step)mothers” in all the cases in which we referred to heterosexual mothers, both biological ones (i.e., heterosexual mothers) and step ones (i.e., heterosexual stepmothers).

References

Baber, K. M., & Tucker, C. J. (2006). The social roles questionnaire: A new approach to measuring attitudes toward gender. Sex Roles, 54,459–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9018-y

Baiocco, R., Santamaria, F., Ioverno, S., Fontanesi, L., Baumgartner, E., Laghi, F., & Lingiardi, V. (2015). Lesbian mother families and gay father families in Italy: Family functioning, dyadic satisfaction, and child well-being. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0185-x

Ballone, C., Pacilli, M. G., Teresi, M., Taurino, A., Paolini, D., & Pagliaro, S. (2023). Same-sex parenting competence evaluation: The role of gender essentialism, political orientation, and attribution of conflict. Social Sciences, 12(3), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030128

Di Battista, S., Pivetti, M., & Salvati, M. (2023). Attitudes toward heterosexual and lesbian stepmothers: An experimental test in the Italian context. Journal of Family Issues, 0192513X221150986. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X221150986

Biblarz, T. J., & Stacey, J. (2010). How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x

Brambilla, M., & Leach, C. W. (2014). On the importance of being moral: The distinctive role of morality in social judgment. Social Cognition, 32(4), 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2014.32.4.397

Clarke, V. (2001, September). What about the children? Arguments against lesbian and gay parenting. Women's Studies International Forum, 24(5), 555–570. Pergamon.

Clarke, V., & Demetriou, E. (2016). ‘Not a big deal’? Exploring the accounts of adult children of lesbian, gay and trans parents. Psychology & Sexuality, 7(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2015.1110195

Claxton-Oldfield, S. (1992). Perceptions of stepfathers: Disciplinary and affectionate behavior. Journal of Family Issues, 13(3), 378–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251392013003007

Claxton-Oldfield, S., & O’Neil, S. (2007). Perceptions of gay and lesbian stepfamilies. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 46(3–4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v46n03_01

Coleman, M., Ganong, L. H., & Cable, S. M. (1997). Perceptions of stepparents: An examination of the incomplete institutionalization and social stigma hypotheses. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 26(1–2), 25–48

Costa, P. A., Almeida, R., Anselmo, C., Ferreira, A., Pereira, H., & Leal, I. (2014). University students’ attitudes toward same-sex parenting and gay and lesbian rights in Portugal. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(12), 1667–1686. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.951253

Dasgupta, N., DeSteno, D., Williams, L. A., & Hunsinger, M. (2009). Fanning the flames of prejudice: The influence of specific incidental emotions on implicit prejudice. Emotion, 9(4), 585. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015961

Di Battista, S. (2023). Gender role beliefs and ontologization of mothers: A moderated mediation analysis. Social Sciences, 12(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010048

Di Battista, S., Paolini, D., & Pivetti, M. (2020a). Attitudes toward same-sex parents: Examining the antecedents of parenting ability evaluation. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 17(3), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2020.1835596

Di Battista, S., Pivetti, M., Paolini, D., & Poliandri, M. (2020b). Dehumanization of same-sex parents in Italy: An exploratory study. Psicologia Sociale, 15(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1482/96296

Di Battista, S., Salvati, M., Ertan, I., & Pivetti, M. (2022). Attitudes toward “non-traditional” mothers: Examining the antecedents of mothers’ competence perceptions. Social Sciences, 11(11), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110495

DiLapi, E. (1989). Lesbian mothers and the motherhood hierarchy. Journal of Homosexuality, 18, 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v18n01_05

Dovidio, J. F. (2001). On the nature of contemporary prejudice: The third wave. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 829–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00244

Duncan, L. E., Mincer, E., & Dunn, S. R. (2017). Assessing politicized sexual orientation identity: Validating the queer consciousness scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(8), 1069–1091. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1236599

Ellemers, N., Pagliaro, S., & Barreto, M. (2013). Morality and behavioural regulation in groups: A social identity approach. European Review of Social Psychology, 24(1), 160–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2013.841490

Ganong, L. H., & Coleman, M. (1995). The content of mother stereotypes. Sex Roles, 32(7), 495. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01544185

Ganong, L., & Coleman, M. (2018). Studying stepfamilies: Four eras of family scholarship. Family Process, 57(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12307

Gato, J., Fontaine, A. M., & Carneiro, N. S. (2012). Escala multidimensional de atitudes face a lésbicas e a gays: Construção e validação preliminar. Paidéia (ribeirão Preto), 22, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2012000100003

Goldberg, A. E. (2022). LGBTQ-parent families: Diversity, intersectionality, and social context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 101517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101517

Gubernskaya, Z. (2010). Changing attitudes toward marriage and children in six countries. Sociological Perspectives, 53(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2010.53.2.179

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based (approach). Guilford Publications

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press

Hequembourg, A. L., & Farrell, M. P. (1999). Lesbian motherhood: Negotiating marginal-mainstream identities. Gender & Society, 13(4), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124399013004007

ILGA-Europe. (2023). Annual review of the of the human rights situation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex people in Europe and Central Asia. https://www.ilga-europe.org/report/annual-review-2023/

Ioverno, S., Carone, N., Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Pagone, P., Pistella, J., ... & Baiocco, R. (2018). Assessing prejudice toward two-father parenting and two-mother parenting: The beliefs on same-sex parenting scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1348460

Jensen, T. M., & Howard, M. O. (2015). Perceived stepparent–child relationship quality: A systematic review of stepchildren’s perspectives. Marriage & Family Review, 51(2), 99–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2015.1006717

Jones, K. N., Brewster, M. E., & Jones, J. A. (2014). The creation and validation of the LGBT Ally Identity Measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(2), 181. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000033

Kinlaw, C. R., Gatins, D., & Dunlap, L. L. (2015). Differences in views of family life according to age, gender, and parental marital status. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 56(7), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2015.1080080

Koleva, S. P., Graham, J., Iyer, R., Ditto, P. H., & Haidt, J. (2012). Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially Purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.006

Kranz, D. (2022). The attribution of parental competence to lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples: Experimental and correlational results. Journal of Homosexuality, 69(7), 1252–1274. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1909395

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: The importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(2), 234. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234

Leal, D., Gato, J., Coimbra, S., Freitas, D., & Tasker, F. (2021). Social support in the transition to parenthood among lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons: A systematic review. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00517-y

Lingiardi, V., & Carone, N. (2016). Madri lesbiche, padri gay: Genitori de-generati? Giornale Italiano Di Psicologia, 43(1–2), 57–80.

Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Ioverno, S., Falanga, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Tanzilli, A., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Homonegativity in Italy: Cultural issues, personality characteristics, and demographic correlates with negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13, 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0197-6

Massey, S. G. (2007). Sexism, heterosexism, and attributions about undesirable behavior in children of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual parents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 3(4), 457483. https://doi.org/10.1300/J461v03n04_05

Massey, S. G., Merriwether, A. M., & Garcia, J. R. (2013). Modern prejudice and same-sex parenting: Shifting judgments in positive and negative parenting situations. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.765257

McLeod, A. C., Crawford, I., & Zechmeister, J. (1999). Heterosexual undergraduates’ attitudes toward gay fathers and their children. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 11(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v11n01_03

Montanari Vergallo, G. (2019). The transforming family: Heterologous fertilization and the new expressions of family relationships in Italian jurisprudence and European Court of Human Rights rulings. Medical Law International, 19(4), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0968533220909412

Moreno, K. N., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2001). Intergroup affect and social judgment: Feelings as inadmissible information. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 4(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430201041002

Morrison, M. A., & Morrison, T. G. (2011). Sexual orientation bias toward gay men and lesbian women: Modern homonegative attitudes and their association with discriminatory behavioral intentions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(11), 2573–2599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00838.x

Morrison, M. A., Morrison, T. G., & Franklin, R. (2009). Modern and old-fashioned homonegativity among samples of Canadian and American university students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(4), 523–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109335053

Pacilli, M. G., Pagliaro, S., Taurino, A., Spaccatini, F., Giovannelli, I., Massaro, G., & Caporale, F. (2017). Impact of gender essentialism on heterosexuals’ negative attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Psicologia Sociale, 3, 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1482/87888

Pacilli, M. G., Taurino, A., Jost, J. T., & van der Toorn, J. (2011). System justification, right-wing conservatism, and internalized homophobia: Gay and lesbian attitudes toward same-sex parenting in Italy. Sex Roles, 65, 580–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9969-5

Park, S. M. (2013). Mothering queerly, queering motherhood: Resisting monomaternalism in adoptive, lesbian, blended, and polygamous families. Suny Press

Pellegrini, V., Giacomantonio, M., De Cristofaro, V., Salvati, M., Brasini, M., Carlo, E., and Leone, L. (2021). Is COVID-19 a natural event? COVID-19 pandemic and conspiracy beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 181, 111011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111011

Planitz, J. M., & Feeney, J. A. (2009). Are stepsiblings bad, stepmothers wicked, and stepfathers evil? An assessment of Australian stepfamily stereotypes. Journal of Family Studies, 15(1), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.327.15.1.82

Rhee, J. J., Schein, C., & Bastian, B. (2019). The what, how, and why of moralization: A review of current definitions, methods, and evidence in moralization research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(12), e12511. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12511

Saint-Jacques, M. C., Godbout, É., & Ivers, H. (2020). People’s opinions and stereotypes about stepfamilies. Journal of Family Issues, 41(11), 2136–2159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19896060

Salvati, M., De Cristofaro, V., Fasoli, F., Paolini, D., & Zotti, D. (2020). Introduction to the special issue: Sexual prejudice and stereotyping in modern societies. Psicologia Sociale, 15(1), 5–14

Salvati, M., & Koc, Y. (2022). Advancing research into the social psychology of sexual orientations and gender identities: Current research and future directions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 52(2), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2875

Salvati, M., Pistella, J., & Baiocco, R. (2018). Gender roles and internalized sexual stigma in gay and lesbian persons: A quadratic relation. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2017.1404542

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

Scierri, I. D. M., & Batini, F. (2019). Misurare l’omonegatività: Validazione Italiana della Multidimensional Scale of Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men [Measuring homonegativity: The validation of the Italian Multidimensional Scale of Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men]. Journal of Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies, 21, 169–190

Štrbić, M., Jeleković, T., Popović, D., Brajković, M., Žukina, P., & Štambuk, M. (2019). Evaluations of parenting by same-sex vs different-sex couples among heterosexual university students: Experimental between-subjects vignette design study. Revija Za Sociologiju, 49(2), 253–281. https://doi.org/10.5613/rzs.49.2.6

Tušl, M., Gato, J., Tasker, F., & Figueroa, V. (2020). Czech psychology students’ attitudes towards same-sex parenting. Psychology & Sexuality, 11(3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1674365

Valiquette-Tessier, S. C., Vandette, M. P., & Gosselin, J. (2016). Is family structure a cue for stereotyping? A systematic review of stereotypes and parenthood. Journal of Family Studies, 22(2), 162–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1049955

van der Toorn, J., Pliskin, R., & Morgenroth, T. (2020). Not quite over the rainbow: The unrelenting and insidious nature of heteronormative ideology. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.03.001

Vezzali, L., Brambilla, M., Giovannini, D., & Paolo Colucci, F. (2017). Strengthening purity: Moral purity as a mediator of direct and extended cross-group friendships on sexual prejudice. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(6), 716–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1196998

Weed, K., & Nicholson, J. S. (2015). Differential social evaluation of pregnant teens, teen mothers and teen fathers by university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 20(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2014.963630

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Silvia Di Battista conceived the idea of this research. Silvia Di Battista and Marco Salvati collected data. All the authors contribute to analyzing and interpreting data. Silvia Di Battista drafted the first version of the paper, and all the authors contributed to finalizing it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Verona.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Battista, S., Salvati, M., Pellegrini, V. et al. Perceptions of Mothers’ Competence and Morality: the Role of Attribution of Responsibility, Gender Role Beliefs, and Sexual Prejudice. Sex Res Soc Policy 21, 352–363 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00828-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00828-w