Abstract

Introduction

Few studies longitudinally investigate parent-teen communication about sex and data are particularly sparse regarding parent–child communication during emerging adulthood.

Methods

This study assesses continuity and change in parent–child sexuality communication over three time points from adolescence to emerging adulthood. It uses interview data from 15 parents in the USA at three time points over an eight-year period from 2012 to 2019 (when the teen was in 7th grade, when the teen was in 10th grade, and after the teen finished high school). Data were analyzed using content analysis.

Results

Our findings showed that parents continued to talk with their emerging adult children about sex and relationships. Whereas the topics of conversation were similar over time, the content of conversations shifted, with a growing focus on specific relationships and situations. Parents described the gender of their teen/emerging adult children as salient in shaping their comfort in talking with them about sex and relationships.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that emerging adulthood may provide ongoing opportunities for parents and their children to talk in open and connected ways about sex and relationships.

Policy Implications

Programs that support family communication about sex and relationships could expand to address the changing needs of adolescents and emerging adults as they develop, and the ongoing role of parents in supporting their children’s health beyond adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents’ and young adults’ sexual behaviors can put them at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancies, with higher rates than other age groups (CDC, 2019; Finer & Zolna, 2016). Emerging adults (18–25 years old), categorized as in-between adolescence and full-fledged adulthood, are particularly at risk, as this developmental stage often entails exploration of intimacy and sexuality (Arnett, 2000). This exploration contributes to high rates of sexual risk-taking, including casual sex reported by 50–80% of college students (Gute & Eshbaugh, 2008; Jonason & Marks, 2009), and over 20% of emerging adults reporting six or more sexual partners (Caico, 2014).

Family sexuality communication during early (10–13 years old) and middle (14–17 years old) adolescence can be effective in reducing teen sexual risk behavior and increasing comfort with family talk about sex (Bastien et al., 2011; Padilla-Walker, 2018; Santa Maria et al., 2015). However, despite the ongoing role of parents in supporting their children’s health in emerging adulthood (Koepke & Denissen, 2012) less is known about the influence of family conversations about sex during this developmental period or the role of emerging adults’ gender in shaping these conversations. Further, no longitudinal studies of family talk about sex track parents’ communication with their children from adolescence into emerging adulthood. Investigation of family talk about sex over time is key to understanding how parents adapt their communication to address their children’s changing needs and developmental processes over these life stages. If talk with parents continues to support health during emerging adulthood, it is important for parents and health educators to understand how parents can talk with their children in ways that support their health during this developmental stage. The current study adds knowledge to the field of parent–child sexuality communication by 1) focusing on family communication during emerging adulthood, a time of little investigation of family talk about sex, and 2) assessing change over time in parent–child communication using three time points: early adolescence, middle adolescence, and emerging adulthood, and 3) exploring patterns of sexuality communication based on teen and emerging adult gender. This paper can guide parents regarding talk with their emerging adult children about sex and inform policy related to sex education programs.

Each stage of adolescence brings distinct developmental and relational processes (Kirby, 2007), which have implications for family sexuality communication. For example, early adolescence often entails exploration of dating, whereas middle adolescents typically become more involved in romantic relationships and sexual activity. During late adolescence/emerging adulthood more serious romantic relationships and sexual activity become normative, as well as exploration of different types of sexual activity, including one-night stands, which increase teens’ risk for STDs and teen pregnancy (Oswalt, 2010).

Parents’ talk with their children about sex and relationships must be understood in the larger context of change in parent–child relationships in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Theorists describe interplay between individuality and attachment during adolescence, which involves interactive dynamics of teens’ growing separation from parents as well as the development of mutuality and connection with them (Grotevant & Cooper, 1985). Early adolescence is characterized by high parental authority and increasing teen separation from parents, which further develops during middle adolescence, bringing more self-direction and distance from parents. Many emerging adults experience increased autonomy and importance of peer relationships, often associated with leaving home for school or work (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992), although they often continue to live at home with a parent during this period, primarily due to financial constraints (Fry et al., 2020). Emerging adulthood is also a time of increased mutuality and connection with parents, when “reliance on parents and self-disclosure become possible again” (Koepke & Denissen, 2012). Therefore, despite often having physical separation from their children at this time, parents’ potential to serve as trusted resources to support emerging adults’ health should not be dismissed. This developmental framework for parent–child relationships fits with findings that teens can be reluctant to talk with parents about sex when they first become sexually active (Crohn, 2010; Golish & Caughlin, 2002). In our previous analysis of qualitative data from participants in the current study, we found that parents perceived teens as more uncomfortable and avoidant of talk with parents about sex in high school than in middle school (Grossman et al., 2018). However, developmental change during emerging adulthood may allow for increased openness in family communication (Morgan et al., 2010). The unique developmental tasks of emerging adulthood (e.g., increased intimacy and exploration of sex and relationships) and this stage of parental-child relationships (showing both separation and growing mutuality) may require different parenting messages and strategies than earlier adolescent stages.

Few studies assess parents’ talk with their emerging adult children about sex and relationships. Quantitative studies in this area suggest that conversations with parents about sex and relationships may be protective for emerging adults’ sexual health (Fletcher et al., 2015) and for sexual self-esteem among college women (Riggio et al., 2014). A qualitative study of college students found that participants wanted parents to have more frequent and open conversations with them over time about sex, addressing topics such as dating and relationships, protection methods and sexually transmitted diseases (Pariera & Brody, 2018). Another qualitative study assessing emerging adults’ talk with their parents about sex in their first and last year of college found that participants at the end of college described their communication with parents as more reciprocal and focused on relationships over time and reported increased openness and comfort with talk compared to their first year (Morgan et al., 2010). With few exceptions, most studies of family sexuality communication during emerging adult include primarily White samples. Recent research identifies variation in how families from different racial/ethnic backgrounds talk with adolescents about sex and relationships (Flores & Barroso, 2017; Widman et al., 2013). Studies are needed that include racially/ethnically diverse emerging adult samples.

While the timing of adolescents’ development varies, to be effective in reducing adolescent sexual risk, sexuality communication needs to adapt to each stage to fit teens’ social, emotional, and sexual development (Kirby, 2007). For example, messages about delaying sex are protective for early adolescents (Grossman et al., 2014), but are likely to be ineffective for older teens who are already sexually active. A quantitative study of college students found that parents’ messages about sex changed after teens become sexually active, becoming more focused on issues such as how to choose a birth control method and recognizing symptoms of STIs (Beckett et al., 2010). However, this study only followed students for one year. A longitudinal quantitative study which followed families from when adolescents were 14–18 years old found little change over time in parent-teen talk about sex, but family talk during adolescence was predictive of safer sex behaviors at age 21. However, this study was not able to assess quality or nuanced variation within this communication (Padilla-Walker, 2018). A further longitudinal study found low levels of parent-teen communication over time (Padilla-Walker et al., 2020). A paper based on earlier data from this same sample found change in parents’ talk with their teens about sex and relationships from early to middle adolescence. For example, when teens were in middle school, parents’ talk with their teens focused on limit-setting and restrictions on dating, whereas when teens were in high school, parents focused on how to engage in healthy relationships (Grossman et al., 2018). However, no studies of family talk about sex include data which spans adolescence and emerging adulthood.

Throughout adolescence, gender plays a key role in family sexuality communication (Ritchwood et al., 2017; Widman et al., 2016), although less is known about its role during emerging adulthood. Both teens and parents may be more likely to talk with same sex family members about sexual issues (Caughlin et al., 2000; Wright, 2009). During adolescence, the content of parent-teen talk about sex and its associations with teens’ sexual behavior are shaped by teens’ gender (Deutsch & Crockett, 2016; Ritchwood et al., 2017; Widman et al., 2016). The content of parent-teen communication often reflects gender-specific messages about sexual behavior (Heisler, 2014; Manago et al., 2015; Shtarkshall et al., 2007; Ward, 2003), such as parents’ greater likelihood to talk with daughters than sons about postponing sex and avoiding boys’ sexual advances (Kuhle et al., 2015). Parents are also more likely to perceive their early adolescent daughters than sons as not ready to talk about sex (Grossman et al., 2018). Studies are needed to explore whether and how the role of gender in family communication about sex changes over time and whether gender differences in communication during adolescence extend into emerging adulthood.

Despite the critical changes in development, sexual behavior, and parental relationships during emerging adulthood, little research investigates continuity and change in parents’ communication with their children about sex. To our knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively explore parents’ experiences of sexuality communication with their children over three time points: early adolescence, middle adolescence, and emerging adulthood. All analyses are exploratory. A prior paper used data from this sample to assess similarities and differences in parents’ perceptions of sexuality communication when teens were in middle school and high school (Grossman et al., 2018). The current paper focuses on a new wave of interview data (after high school) for a sample of parents in the United States, which compares parents’ perceptions of family talk about sex when their children are emerging adults with early and middle adolescence. It also explores the role of teen/emerging adult gender in family talk about sex.

Methods

Recruitment and Participants

This longitudinal interview sample consisted of parents of adolescents recruited from three schools who participated in a sex education evaluation study when the students were in middle school. Get Real: Comprehensive Sex Education That Works is a 3-year comprehensive sexuality communication program developed by Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts which emphasizes delaying sex while providing medically accurate information about protection. Researchers interviewed participating parents at three time points: when the teen was in 7th grade (Time 1, age = 13–14 years old), when the teen was in 10th grade (Time 2, age = 15–16 years old), and after high school (Time 3, age = 21–22 years old) (see Grossman et al., 2014 for more information about school recruitment and consent). Parents completing interviews at Time 1 and Time 2 were contacted again 4 years later by phone, text, or email and asked to complete an active consent form to participate in a Time 3 interview. Outreach to parents included multiple contacts at various times of day and included all available contact information provided by parents at previous waves of data collection. Of the original 29 parents interviewed at Time 1, 18 parents completed the interview at Time 3, eight families were unreachable, and three families declined to participate. The analysis sample for this paper only includes parents who completed interviews at all three waves. Fifteen parents met this requirement. While the sample is small, it is comparable to that of other qualitative longitudinal studies of adolescents and families (e.g., Lipstein & Britto, 2015). Three parent interviews were excluded from this sample, because the parents did not complete interviews at all three time points.

At all three time points, the research team conducted interviews over the phone. For the final sample who had data at all three waves (N = 15), 14 participants completed interviews in English, and one parent completed an interview in Spanish. Interviews took 45–60 min and were translated, when needed, and transcribed. Parents were given $25 at Time 1 and Time 2, and $40 at Time 3 for their participation in the study. Each parent was asked to create a code name at Time 1 to protect their confidentiality; those pseudonyms are used here. At the end of each interview parents were given a resource list with contact information for organizations supporting youth and family social, emotional, and sexual health. Human subjects’ approval was granted from The Institutional Review Board at Wellesley College to conduct this work at each time point (January 2011, December 2013, August 2018).

The current sample includes thirteen mothers and two fathers. Close to half of this sample self-identified as Black/African American (47%) or as White/Caucasian (47%), and 7% as Hispanic. Over a third of parents (38%) graduated from college or received more training after college, 27% had some college education and 33% had graduated from high school or had some high school education. Participants described their children as eight male and seven female-identified. At Time 3, parents described their emerging adult children as either working (56%) in jobs such as food service and retail, or in college (44%), which included trade school and four-year colleges.

Interview Protocol

Prior to interviews, participants were reminded of the purpose of the study and told that they may feel a bit embarrassed or uncomfortable, and that they could choose not to answer any questions. Interviews followed a semi-structured format, with questions that addressed parents’ communication with their teens and emerging adults about sex and relationships at each time point. Specifically, we asked parents about the content of their communication with their teens/emerging adults, their comfort with this communication, and their understanding and experiences of talking with their teens/emerging adults about sexual issues. Interview questions were similar across all three time points. For content of communication, interviewers stated, “I’m going ask you about some things that families sometimes talk about. For each one, will you tell me whether you’ve talked about this topic with [teen’s name]? Then I’ll ask you to try to remember a conversation you had about each topic.” To address comfort, interviewers asked parents, “How comfortable are you talking about sex and relationships with [teen’s name]? What do you think makes it [comfortable/uncomfortable] for you to talk with [teen’s name] about sex and relationships?” Time 2 and Time 3 interviews included questions about change over time in communication about sex and relationships which were not included at Time 1. For example, at Time 3 participants were asked about their comfort with talk about sex, “Has that changed since [teen’s name] was in high school? [If yes] why do you think this has changed?” Interviewers at each time point included the PI and additional interviewers. There was overlap in interviewers at each time point, as well as interviewers unique to a specific wave of data collection. The PI trained all interviewers to understand the protocol and sample. To minimize bias, such as social desirability related to interviewing participants over multiple time points, the research team discussed bias in interview training. Further, reliability checks included a team member who did not conduct any of the project interviews. Prior to each interview, interviewers were asked to review names and background information for each participant such as their family background, living status and names of family members to avoid asking information already known to the research team about participants and their families.

Analysis

Content analysis was used to systematically identify themes in the interview transcripts (Patton, 2002). In the initial coding of transcripts, overarching themes were identified. These were then discussed, revised, and named by the first and second author. After a theme was identified, additional examples were sought in other interviews. To explore continuity and change in parents’ approaches to and discussion with their teens about sex and relationships, the authors explored how the same themes were addressed over three time points. To ensure coding trustworthiness, the first and second authors conducted reliability checks for coding, in which reliability equals the number of agreements divided by the total of codes (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The researchers coded data in groups of five participants, discussing inconsistencies after comparing each round of coding. The final intercoder reliability of 95% represented a high-level agreement between the two coders. The themes were not mutually exclusive, in that one participant’s responses could generate more than one code. NVivo 10.0 (QSR International, 2012) was used to facilitate coding.

Results

The first three themes reflect parents’ experiences of and approaches to talk with their children about sex and relationships: Reasons for sexuality communication, Comfort (or discomfort) talking about sex, and Perceptions of children’s engagement with family sexuality communication. The final three themes focus on whether and how parents talk with their teens about specific content areas: Talk about dating and relationships, Talk about sexual risk and protection, and Talk about sexual behavior. To provide a window into continuity and change in parents’ approaches to communication with their children about sex and talk with their children about sexual topics, the results provide examples of individual parents’ responses over multiple time points. In addition, the overall percentages of themes across the group for each time point are reported. Table 1 includes the overall percentages for each theme and subtheme across each time point and Table 2 includes comparisons based on teen/emerging adult gender.

Reasons for Talk

In the Reasons for sexuality communication theme, parents described why they talked with their children about sex and relationships. At Time 1 (73%, n = 11) and Time 2 (60%, n = 9), many parents described why they talked frequently with their teens about sex and relationships compared to fewer parents at Time 3 (13%, n = 2). Parents’ descriptions for why they talked with their children about sex had common themes across all three time points, often relating to protecting teens from risk. However, parents’ descriptions at Time 1 of their reasons for talk with their teens often focused on preparing their children for future relationships compared to addressing current relationships at Time 2 and Time 3, with a focus at Time 3 on concrete and specific issues related to teens’ current relationships and sexual behavior. For example, Maria shared her reasons for talking with her son about sex at Time 1 “I want my son to learn from me before he learns from one of his friends in school,” and at Time 2 “Now I can talk to him with more details than before. Before I talked to him a little more limited for age, but now the topics are broad.” At Time 3, Maria explained why she talks with her son now, “He is now on another level, he has his girlfriend, he is with her, he tells me that he wants that intimacy with his girlfriend and the thing is a little more different. There is no curiosity, it is already in another stage, on a more adult stage.” Another mother, Susan, talked about why she talks with her daughter about sex. At Time 1 she shared “She’s old enough for certain things and she’s a teenager now, so I try to talk to her. Yeah, I think that was the best time to talk to her. She’s not a young lady yet, but it is soon. So I’m trying to prepare her.” At Time 2 Susan shared, “I thought it was not necessary too much before because she wasn’t really hooking up with people. But now she’s more social and she’s going to be more adult now. She wants to have a boyfriend, that’s when I know it’s probably the time.” Finally, at Time 3 Susan shared why she talks with her daughter about delaying pregnancy and avoiding STIs, “Just to make sure she stays safe, like sexually protecting herself from the STDs and pregnancy at a young age. She’s 21 and technically there are kids that have kids at that age, but I would want her to secure her future and be established so she’s not struggling.”

At Time 3, parents often described reasons they had little or no talk with their children about sex or relationships (73%, n = 11) as compared to Time 1 (40%, n = 6) or Time 2 (40%, n = 6). At Time 1 and Time 2, parents’ explanations for no talk or little talk with teens about sex or relationships focused on perceptions that teens lacked readiness to have these conversations or were not interested or involved in sex or relationships. In contrast, parents’ primary explanations at Time 3 for not talking or low levels of talk with their children related to teens’ growing maturity and experience and relationship status. For example, Rose explained why she did not talk to her daughter at Time 1, “We didn’t go over details because she’s just waiting to get her period, so she’s kind of like a little girl still.” At Time 2, Rose shared about her daughter, “None of her friends have boyfriends so I don’t think it’s um—I think once that starts happening, I’ll probably start opening up more conversations like that. But right now it’s kind of like I know she’s not dating anybody or seeing anybody because she’s home with us a lot. So I think once that starts happening, I will talk more.” However, at Time 3 Rose described why she rarely talks with her daughter about these issues, “I took her to get the birth control pill and I’ll text her to say, ‘It’s here.’ But I don’t really ask her too much—since it is kind of a serious relationship, it’s like I don’t…I think if it was more of a casual—you know, just kind of starting dating and this and that, I would be more inquisitive.” Another mother, Cara, talked about why she rarely talked with her daughter at Time 1 “I really feel like [my daughter] is far away, you know, from—from, you know, from that. And I know she’s 13, but… um we just—I just know she’s definitely far away from even dating or even being out where—because we have um—how do I say this? Me and my husband, you know, we make sure we know where Sasha is at all times.” At Time 3, Cara discussed how her daughter’s learning from her recent pregnancy relates to why she does not talk with her about sex, “I mean it doesn’t come up often. I think she knows a lot. She learned a lot by going through, you know, the woman’s clinic about, you know, how to protect yourself from future pregnancies.”

Parent Comfort

This theme addresses parents’ comfort and discomfort in talking with their teens about sex and relationships. At all three time points, most parents described feeling comfortable talking with their children about sex and relationships (Time 1: 73%, n = 11, Time 2: 93%, n = 14, Time 3: 80%, n = 12). At Time 1, many parents described relative ease in talking with their teens about sex. At Time 2 and Time 3, many parents described ways their comfort increased over time, often due to their teens’ development and shifting parent–child relationships. Susan’s responses show how her comfort changed over time. At Time 1, Susan shared “I would say very comfortable (talking with her daughter about sex),” and at Time 2 she said, “[My daughter] reached her age now that I’m more comfortable with her.” At Time 3, Susan shared about her daughter, “She’s opened up and I opened up to her too. I think when she was in high school, she was more shy or more—more private. She’s more opened up now.” Other parents were similar in describing their level of comfort across all three waves. For example, at Time 1 Cordelia shared, “I don’t have any trouble talking to my kids about sex,” and at Time 2 she mentioned she was “Very comfortable—pretty comfortable. I’m not embarrassed by the topic and I don’t want my kids to be embarrassed by the topic, so they could say anything to me and I would hope that I could say anything to them.” Lastly, at Time 3 Cordelia said, “I’m pretty comfortable. I’m not a shy person about things. Like I’ve always—you know, I hate the thing where menstruation is supposed to be something you’re embarrassed about and you can’t—you can’t shop for the things. I’ve always told my girls to be out in the open. And similarly, I’m not—I’m not ashamed or embarrassed to talk about these things.”

Some parents at Time 1 and Time 3 described discomfort in talking with their children about sex (Time 1: 33%, n = 5, Time 3: 27%, n = 4), but no parents at Time 2 described discomfort. Parents’ descriptions of discomfort often related to feeling ill at ease discussing sex, with some parents at Time 3 focusing on the role of gender in their discomfort. For example, Jada shared her discomfort in talking with her son at Time 1, “I’m still somewhat uncomfortable... to me it’s more the awkwardness of finding the right words at the right time. But, you know, the sigh of relief is, no matter how uncomfortable I am, I’m willing to do it” and her decreased comfort talking with her son about sex as he got older, “I think I pulled back more…It was definitely a gender thing. Because with my daughter I still talk to her about things like that (Time 3).” A father, Rian, explained his daughter’s openness at Time 1 made him uncomfortable, “Um she’ll just randomly ask like how old was I, or what age you think is too young. Like you know, those are the kind of questions verbatim that’s been asked. You know, and it kind of throws me off. But I do appreciate that um, you know, it’s open enough to ask me something like that,” and at Time 3 some conversations about sex were still outside of his comfort zone, “no, because it’s still—you know, even though I’m comfortable, it’s probably to a certain extent.”

Teen/Emerging Adult Engagement in Talk with Parents

The third theme, Perceptions of children’s experiences of talk about sex, explores how parents view their children’s responses to talking with them about sex and relationships. It includes subthemes of Positive Engagement and Negative Engagement. Most parents at all 3 time points described their children’s Positive Engagement in conversations about sex (67%, n = 10 at Time 1, and 67%, n = 10 at Time 2, 87%, n = 13 at Time 3), particularly at Time 3. Time 1 parent responses often focused on teens expressing positive engagement by asking questions. At Time 2 and Time 3, parents often commented that their children seemed open and comfortable with conversations about sex. For example, Jada at Time 1 talked about the questions her son asked about sex, “[My son] has actually asked me what fellatio is because of that book that I bought him…so the book has actually been a really good tool for us. It actually forced me talk and I think they get a broader picture, and I think that they don’t—it’s not taboo for them anymore.” At Time 2 Jada described her son’s response to her communication, “He kind of listens and just doesn’t say anything. It’s like he’s putting it in his pocket somewhere, and maybe he’ll use it someday.” At Time 3, Jada explains, “he’ll occasionally talk about when they have—you know, when they’re [he and his girlfriend] having disagreements or um, you know, um if he feels like he’s, you know, being too smothered—that type of thing.” Another mother, Alex described her son’s engagement when they talked about sexually transmitted infections at Time 1, “I was like, ‘That’s the way that you can catch something that you can never, ever, ever get rid of because there’s no medicine for it.’ He was like ‘For real?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, for real.’” At Time 3, Alex described her son’s response when she talks with him about sex, “He got comfortable as he got a little older.”

Parents’ descriptions of their children’s Negative Engagement with conversations about sex and relationships were similar over time, with close to half of parents describing negative engagement from their children (Time 1: 40%, n = 6, Time 2: 60%, n = 9, Time 3: 53%, n = 8). At all three time points, parents’ descriptions of their children’s disengagement often included avoiding conversations, eye-rolling and perceived embarrassment. Cara described how her daughter responded to their conversations about dating at Time 1, “I talk to her about really I don’t want her dating in high school. She just gives me a look.” At Time 2, Cara shared how her daughter responds to conversations related to delaying sex, “Well I want to teach her actually to wait because when you’re young you can make um, you know, wrong decisions. I mean I hope she listens to me. You know? I got a good feeling she does, but she puts on an act. You know, sometimes she puts on, you know, she don’t want to tell me, you know, because she’s at that teenage stage where she thinks she knows everything.” Lastly, at Time 3, Cara talked about how her daughter has other people she can ask for help when she feels uncomfortable, “It might be uncomfortable for her to talk to me totally about everything. Which I’m happy she has other people besides me…because I’m her mom still and it’s like, ‘Oh mom,’ you know?” At Time 1 Jasmine talks about her daughter’s reactions to her conversations about sex, “We talk about it all the time, and I always talk about it, you know, if we’re watching movies and something comes on. You know, she’s always like, ‘Ew mom, that’s nasty.’” Jasmine shared similar experiences at Time 2, “She’ll say, ‘Ma, I already know. I already know’” and Time 3, “I guess she’s older now and whatever. And every thing I do—I talk to her, I try to talk to her about every little thing or whatever…and she’ll be like, ‘I know, Ma.’”.

Talk About Dating and Relationships

The first content theme, Talk about dating and relationships, showed high levels of talk at all three time points (Time 1: 100%, n = 15, Time 2: 93%, n = 14, Time 3: 100%, n = 15). However, the focus of conversations shifted at each time point. At Time 1, conversations centered on rules for dating and relationships. At Time 2, communication often addressed teens’ interest or involvement in dating and relationships. At Time 3, conversations often focused on actual relationships, rather than waiting for their children to date or exploring new relationships and parents often described conversations that addressed their children’s current relationships, how to manage them, and giving advice about what is healthy and unhealthy within those relationships. Kevi at Time 1 described her conversations with her son about dating, “I think right now it’s that he’s too young. And I—I say about 15. But there’s no um set rule. But that’s what I suggested to him.” At Time 2, Kevi described a conversation with her son about his involvement in relationships, “I always tell him how to have respect for his girlfriend and it will come back to him as well, and never to be in a bad relationship.” At Time 3, Kevi described how she talked to her son about his relationship “I always say, you know, ‘A relationship goes both ways. You both have to give and take. And you know, if you’re feeling like things aren’t going right, then you guys need to break apart.” Cordelia shared her experiences talking with her daughter about dating at Time 1, “I think it’s premature now, they’re 13. I tell them I don’t know the number because I don’t know how mature they’re going to be at age X. So I’d rather not put an age out there until I see them at that age,” and their conversations about relationships at Time 2, “We’re constantly having discussions about their feelings—they find this one attractive, they find that one attractive.” At Time 3, the conversation shifted to focus on her daughter’s current relationship and her response when her daughter wanted to move in with her boyfriend, “And I tell her, you know, ‘If you get yourself into this situation where you’re living with this guy and he’s abusive but you have nowhere to go and you have no economic choices, then you’re going to be screwed.’”

Talk About Sexual Risk and Protection

This theme showed high levels of communication across all three time points, with Time 1 at 93% (n = 14), Time 2 at 100% (n = 15), and 93% (n = 14) at Time 3. Some aspects of talk were similar across all three time points, with a consistent focus for many parents on delaying pregnancy and using condoms. However, at Time 1 and Time 2, parents’ conversations with their teens were often hypothetical and focused on preparation for future relationships. A new focus in Time 3 was conversations exploring and planning for parenthood. Maria described conversations with her son at Time 1, “Yes, this one time I was at the store. And I was standing where they sell the contraceptives. He looked at them and he started to laugh with his little cousin who is the same age as him. So I told him ‘It’s fine to laugh, but this is no laughing matter. You have to look at this like as a serious matter. This is something normal that people use in order to prevent pregnancy, to keep from ending up pregnant.’ that’s what I told him.” At Time 2 Maria shared, “Yes. I’ve told him that when he feels like he’s ready, that he let me know and I’ll take him to the hospital or to talk to his father so that he can get him condoms and that. But he tells me, ‘Oh Mommy, I’m not thinking about that now. I want to finish my studies first and the girls are crazy.’” At Time 3 Maria describes how her son is now thinking about parenthood, “He asks me what is the most appropriate age to have children, we talk a lot about that, and he tells me that in three or four years, he says he has to have his first son. He wants to be stable, wants to get married first and then have a child.” Lynn describes her engagement with her son about teen pregnancy at Time 1, “I remember watching the American Teenage show… and this one couple, the girl is pregnant, the boy thinks he’s supposed to do the right thing, so he decides to marry her… And then his father, the boy’s father, decides instead of paying for a wedding, he would like to buy them a condo. And so they were very, very excited and now they’re starting to pick out um colors to paint the walls in the condo. And when that show was over, I just had a down-to-earth conversation with both of the kids. I was like, ‘Nobody is buying you a condo if you get anybody pregnant.’ (Laughs) ‘And I am not raising anybody else’s children.’” At Time 2, Lynn shared, “’ My son just pulled a condom out of his back pocket. And we were like, ‘Why do you have that? Where did you get that?’ And he was like, ‘What? I always carry a condom.’ And I was like, ‘Really?’ But it turns out we were at a street fair that day and they were handing them out, so that’s funny. And I did have an opportunity to tell him that they have expiration dates and he needs to look at them to make sure that if he ever needs to use one that it’s not expired.” At Time 3, Lynn described talk with her son about future parenthood, “He doesn’t seem to be somebody that wants to have children because of the future of climate change. But he has mentioned more than once that he would be willing to adopt.”

Talk About Sexual Behavior

The final content theme, Talk about sexual behavior, addresses how parents talk with their children about sexual activity, such as conversations about delaying sex or talk about teens’ sexual relationships. The majority of parents at all three time points addressed sexual behavior (Time 1: 73%, n = 11, Time 2: 60%, n = 9, Time 3: 67%, n = 10), but as with talk about STIs and pregnancy, parents’ discussions with teens at Time 1 and Time 2 were often more hypothetical and future-based than their conversations at Time 3, as well as more focused on delaying sex. At Time 3, parents focused more on how to manage sex within the context of relationships. Rose explained what she told her daughter about sex at Time 1, “I want her to be in love, not to feel cheap or any of that type of thing. I want her to be really ready.” At Time 2, Rose described, “I think she feels not ready but I haven’t asked her. I think it scares her, to tell you the truth. I mean just the whole, you know, relationship thing—being close to somebody like that. Because right now it’s like—it’s not—it’s just in her place—I mean it’s not her time. But going off to college, I feel like I’m going to have to prepare her more.” Lastly, at Time 3 Rose talked about her daughter’s sexual behavior in her current relationship, “She told me like she wasn’t ready [for sex] and he [her boyfriend] was understanding about it.” Kevi described her response when her son asked when he was old enough to have sex at Time 1, “He actually asked me one time when was the right age. And I said, ‘It’s not more of an age, it’s more when you’re in love with somebody.’” At Time 2, Kevi described conversations she had with her son about having sex, “I gave examples of people that have had sex—unprotected sex—and have had babies, um whether it be somebody in our neighborhood or whatever, and just how much responsibility it is and I don’t think they really think of it before and it’s something that you really, really have got to think about because it’s for the rest of your life.” Finally at Time 3, Kevi described a conversation with her son about exploring sex in new relationships, “When he and his girlfriend broke up this year, I just said to him, ‘All I ask is that you don’t jump right into a relationship—you take some time. And when you are jumping into it, take every consideration into waiting to have sex.’”

Role of Teen/Emerging Adult Gender in Family Talk

This section provides preliminary findings for the role of teen gender in family communication about sex, both qualitatively (parents’ responses which reflected on the role of gender) and quantitively (frequency of responses based on parents with male and female teen/emerging adult children). As the sample is primarily mothers, analyses did not address parent gender. For the thirteen mothers in the sample, seven had children who identified as female and six as male. For the two fathers in the sample, one father had a child who self-identified as male and one as female. Given small numbers of parents of male and female emerging adults in this sample, results address tendencies rather than statistical differences. Only one theme, Parent Comfort, showed responses where parents consistently addressed gender as playing a role in their experience of talk about sex. At Time 3, several parents’ explanations for their own discomfort with talk about discussing sexual topics with their children addressed discomfort talking with their children who identify with a different gender from themselves, with a focus on mothers’ reported discomfort talking with their male children.

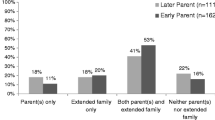

For themes focused on the process of family communication about sex, the percent of parents who addressed different themes often varied based on their children’s gender (see Table 2) as well as by time point. For Reasons for Talk, patterns suggested that at Time 2 and Time 3, parents more often described why they talked with their male than female children, while parents appeared more likely to share why they did not talk with female teens at Time 1. For Parent Comfort, parents tended to report comfort talking with their female compared to male children about sex, which was evident at all three time points. Parents also tended to express more discomfort taking with male than female teens at Time 1. For Teen/Emerging Adult Engagement in Talk with Parents, parents tended to describe both positive and negative engagement with talk for male and female teens.

Themes focused on content of talk with parents showed more consistency than process themes across parents of male and female children. The likelihood of parents’ reported talk with male and female children appeared similar for Talk about Dating and Relationships and Talk about Pregnancy and STIs. However, parents seemed more likely to report talk with their male than female children about sexual behavior at all three time points.

Discussion

Findings across the three waves of data suggest that parent–child talk about sex and relationships is not limited to adolescence. While each stage brings shifts to the content and process of sexuality communication, the communication continues. These results fit with an understanding that emerging adulthood can be a time of connection and mutuality with parents, who continue to be key sources of support for their children (Koepke & Denissen, 2012).

However, parents also described less need to talk with their emerging adulthood children about sex, based on their children’s growing maturity and knowledge, reflecting an awareness of their children’s development. Parents’ reasons for talk also shifted with each time point, moving from preparation for relationships, to relationship exploration, to concrete issues and decision-making in more serious relationships. These changes in how parents talk with their children about sex and relationships reflect developmental stages of adolescent and emerging adult relationships (Arnett, 2000; Kirby, 2007), suggesting that parents’ communication with their children adapted to reflect their children’s changing needs and relationships contexts.

Most parents described comfort talking with their children about sex and relationships, particularly at Time 2 and Time 3. Parents described growing comfort with talk as their teens matured and they grew accustomed to their own roles in addressing sexual issues, which may reflect strengthening parent–child relationships during emerging adulthood (Koepke & Denissen, 2012). More parents described discomfort at Time 1 and 3 than Time 2. Discomfort at Time 1 may reflect parents’ perceptions that it is more difficult to talk with younger than older teens about sex (Coffelt, 2010) and parents’ concerns that younger children may not be mature enough for these conversations (Pluhar et al., 2008; Tobey et al., 2011). Emerging adulthood marks the end of adolescence, which may lead to less clarity about parents’ roles in talk with their children about sex. In contrast, parents may feel clear about the importance of their roles in talking during middle adolescence about sex. Parents’ explanations for discomfort also tied to their children’s gender, with some mothers describing discomfort talking with their male children about sex and relationships. It may be that the time of transition between adolescence and adulthood raised more questions for parents about how to talk with children from a different gender about sexual issues. Given that most of our sample is mothers, it would be useful in future research to investigate parental comfort and discomfort among father-daughter and father-son pairs.

Parents described their children’s ongoing positive engagement over time in talk about sex. At Time 1, parents described teens’ engagement in the form of asking questions, while their descriptions at Time 2 and Time 3 focused on their children’s increasing openness and comfort in talking about sex and relationships. Parents described their children’s negative engagement in similar ways over time, including eye rolls, verbal push-back, and avoidance. Overlap in parents’ descriptions of their children’s positive and negative engagement at each time point suggests that children’s responses to talk about sex is not monolithic. Their disengagement may reflect discomfort in discussing sexual issues, while their engagement may reflect a wish to understand and discuss these topics. Teens’ patterns of engagement and disengagement may also reflect their emotional lability at different developmental stages. These findings suggest that a teen’s avoidance of talk in one moment does not necessarily signal a lack of interest in talking about sex or suggest that a teen will not respond to a conversation at another time. Parents need to show persistence and tolerance of their teens’ mixed messages about these conversations, and look for opportunities when their teens may be open to talking about sexual issues.

Parents’ reports showed that conversations with their children at all three time points often addressed topics of sex and relationships, suggesting that issues of sex and relationships remain a focus of conversations across multiple stages of adolescent and emerging adult development. However, the content of conversations shifted over time, with a growing focus on specific relationships and situations as children got older. This shift occurred across all three content areas: dating and relationships, risk and protection, and sexual behavior. At Time 1 and Time 2, parents described a focus on preparing their children for sex and relationships, laying out ground rules, and exploring hypothetical situations. In contrast, at Time 3 parents described discussions with their emerging adult children about how to address specific relationship and sexual situations. At Time 3, parents also described a new focus on planning for parenthood, such as discussing when to have children, which has been little documented in prior research. Rather than a primary focus on delaying sex, which is a key message parents share with their adolescent children (e.g., Elliott, 2010; Manago et al., 2015), the focus during emerging adulthood on planning for parenthood suggests a major transition in parenting roles as parents shift from a risk prevention focus to one that involves support for navigation of new developmental roles. Exploration of this shifting parental focus would be a productive area for future research, which could also be used to guide parents’ ongoing conversations about this topic. The changes in parents’ talk about sex and relationships suggest that parents adapt their talk to fit the developmental issues facing their children at different time points, consistent with findings that parents’ sexual messages shift after teens became sexually active (Beckett et al., 2010). They also suggest the ongoing relevance of parents in providing support and feedback to their children into early adulthood.

As found in multiple studies (Bulat et al., 2016; Deutsch & Crockett, 2016; Widman et al., 2016), gender plays a role in the content and process of talk about sex and relationships. This study suggests that the role of teen and emerging adult gender changes over time and may be particularly relevant for how and why parents and their children engage with each other about sexual topics. While parents’ explicit focus on gender was limited to their descriptions of comfort and discomfort talking with their children about sex, the data suggest some gendered patterns in communication processes over time. Parents’ focus on reasons for not talking with teens at Time 1 largely reflected their lack of talk with daughters. This may relate to gendered ideas about girls’ readiness to talk about sexual issues and a perceived need to protect them from talk about sex and relationships (Grossman et al., 2018). Parents reported higher comfort with female children at Time 1 and Time 3, but not Time 2 may reflect parents’ clarity described earlier in the discussion at the importance of talking with all teens during middle adolescence. Perceptions of risk for their male children at this developmental period and their need to actively address sexual issues may over-ride their discomfort in talking with opposite gender teens. Consistent with this reasoning, parents were most likely to describe both positive and negative engagement from their male teens at Time 2, suggesting that middle adolescence may be a time when parents are actively reaching out to talk with their sons about sex and relationships, with a mixed reception. Content of communication was relatively consistent across teens’ and emerging adults’ gender, although parents were more likely to describe talk about sexual behavior with male than female children across all three waves, which may reflect traditional gender role socialization, as studies show that parents often focus more on sexual behavior with their sons while avoiding talk about sex or focusing on abstinence messages with their daughters (e.g., Kuhle et al., 2015).

Most research on parents’ talk with their children about sex and relationships and its effects on sexual risk behavior focuses on adolescence (e.g., Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012; Widman et al., 2016). This paper adds to a growing body of research which indicates that parents’ roles in talking with their children about sex extend beyond adolescence (Fletcher et al., 2015; Morgan et al., 2010; Pariera & Brody, 2018). This study suggests that at least from parents’ perspectives, communication continues into emerging adulthood. Further, parents’ changing descriptions of conversations over time suggest their capacities to change and adapt to fit the changing needs and developmental stages of their children. Rather than ending communication about sex and relationships after adolescence, parents may have potential to support and guide their children beyond this period.

This study’s findings show continuity of parental engagement with teens in talk about sex and relationships over time, even as the content and process shifted. While not directly assessed by this study, conversations these parents had with their early adolescent children may have laid the groundwork for their ongoing communication about sexual issues. The US Department of Health and Human Services (2021) recommends that parents talk with their children about sex “early and often” addressing the issues and questions that come with each stage of development. It may also be helpful for parents to build their own comfort with talking about sex when their teens are young, since teens may push back against these conversations when they become sexually active, for fear parents will judge them or worry about their sexual behavior (Crohn, 2010).

Quantitative studies are needed to assess whether and how parent–child conversations continue to support health and reduce risky sexual behaviors into emerging adulthood. Longitudinal qualitative studies with larger and more representative samples would also provide a more complete picture of continuity and change in family communication about sex and relationships. In addition, future research which includes matched pairs of parents and their emerging adult children would bring a more holistic picture of family communication, and could investigate whether and how emerging adults view family communication about sex differently from their parents, as findings show for adolescents (Atienzo et al., 2015; Grossman et al., 2017). Regardless of the approach, assessment of talk with parents about sex and its relationships with emerging adults’ health must reflect the changing content of talk with parents and expectations for emerging adult health and development.

There are several limitations of this paper. First, this sample primarily consists of parents who are highly engaged in conversations with their children about sex. These families’ participation in a comprehensive sex education program when their teens were in middle school, which included activities to support parent-teen communication, may have increased parent-teen talk about sex and relationships. Future research would benefit from inclusion of parents in longitudinal research who talk less or do not talk at all with their teens about sex and relationships during adolescence. This is also a small sample, particularly when split by teen gender, so results should be considered preliminary. However, this longitudinal sample’s unique data, investigating communication over eight years of adolescent and emerging adult development, suggests that it contributes to our understanding of family communication, despite the small sample size. Several parents from our original sample did not complete interviews at all three time points, largely because family contact information had changed, and some families were unreachable at later waves of the study. These parents showed some demographic differences from parents who completed all three waves of interviews. To explore family communication longitudinally, only parents who completed all three waves of interviews were included in the current analysis. In addition, there were only two fathers in this study.

Mothers are more likely to talk with their teens about sex and relationships and are the focus of most research on sexuality communication (Widman et al., 2016). However, research suggests that fathers can play an important role in this communication (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012; Wright, 2009), and future studies would be strengthened by a greater focus on father-teen sexuality communication. This study consists of a sample that is diverse in terms of participants’ racial/ethnic background and education background and achievement, which is a strength of this research. However, given the small sample size and the multiple racial/ethnic groups included, we were unable to explore similarities and differences across these groups. Given variation in family sexuality communication across racial and ethnic groups (Malacane & Beckmeyer, 2016; Wright, 2009), future research would benefit from following individual racial/ethnic groups over time or comparing communication across groups. Further, with few exceptions (Flores & Barroso, 2017), little research investigates the role of social class in family sexuality communication, which would be a useful area of exploration in future research. Despite these limitations, this in-depth exploration of parents’ experiences of and perspectives on family sexuality communication over three time points provides a unique window into parents’ perspectives on family sexuality communication over multiple stages of adolescent and emerging adult development.

Research on family talk about sex documents the importance of ongoing parent–child conversations beyond “the talk” to support teens’ sexual health (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012; Widman et al., 2016), although most parents report only one or few conversations with their teens about sex (Padilla-Walker, 2018). This study’s findings extend that framework to suggest a continuing role for parent–child talk throughout young people’s development. However, parents may face challenges when their comfort or lack of it, and their children’s engagement in conversations about sex and relationships, may not always fit together smoothly. Research suggests that parents struggle with both teens’ resistance to talking about sex and their own discomfort with these conversations (Elliott, 2010). For parents, this may require patience as their children may show avoidance of or negative responses to parents’ efforts to talk with them about sex and relationships, as well as tolerance of their own discomfort with these conversations, which may vary over the course of development.

On a policy level, most school-based sex education programs which include parent involvement focus on middle school or high school-age youth (Marseille et al., 2018; Santa Maria et al., 2015). Whereas programs for emerging adults which support family engagement may not be realistic, existing sex education programs would benefit from a focus on the changing needs of adolescents and emerging adults as they develop, and the ongoing role of parents in supporting their children’s health beyond adolescence. Programs which provide online guidance for parent-teen communication could add a component that addresses an ongoing role for parents beyond adolescence. While the health benefits of teen-parent communication are clear (Grossman et al., 2014; Secor-Turner et al., 2011; Widman et al., 2016), more resources are needed that recognize health-promoting roles that parents can play across their children’ development. Specifically, parents may need guidance as to how to understand family sexuality communication as a process that spans their child’s development, and to adapt the content and process of family sexuality communication as their children develop.

Conclusion

This study’s findings support an understanding of parenting roles as ongoing during emerging adulthood as most families continued to talk about sex and relationships. In this study, parents adapted their communication with teens to reflect their development over time. Overall, these findings suggest that emerging adulthood may provide new opportunities for parents and their children to talk in open and connected ways about sexual topics. Our findings for ongoing family sexuality communication suggest that supports for parent–child talk about sex and relationships should not be limited to adolescence. This study can encourage parents to maintain a health-promoting role by continuing to talk and engage with their teens into emerging adulthood. It can also inform sex-education programs as to the need to continue health education beyond adolescence and into early adulthood.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging Adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 477.

Atienzo, E. E., Ortiz-Panozo, E., & Campero, L. (2015). Congruence in reported frequency of parent-adolescent sexual health communication: A study from Mexico. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 27(3), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2014-0025

Bastien, S., Kajula, L. J., & Muhwezi, W. W. (2011). A review of studies of parent-child communication about sexuality and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health, 8, 25–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-25

Beckett, M. K., Elliott, M. N., Martino, S., Kanouse, D. E., Corona, R., Klein, D. J., & Schuster, M. A. (2010). Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children’s sexual behaviors. Pediatrics, 125(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0806

Bulat, L. R., Ajduković, M., & Ajduković, D. (2016). The role of parents and peers in understanding female adolescent sexuality—Testing perceived peer norms as mediators between some parental variables and sexuality. Sex Education, 16(5), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2015.1110691

Caico, C. (2014). Sexually Risky Behavior in College-Aged Students. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine, 4, 354–364. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2014.45043

Caughlin, J. P., Golish, T. D., Olson, L. N., Sargent, J. E., Cook, J. S., & Petronio, S. (2000). Intrafamily secrets in various family configurations: A communication boundary management perspective. Communication Studies, 51(2), 116–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970009388513

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, National overview of STDs. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2019/overview.htm#Chlamydia

Coffelt, T. A. (2010). Is sexual communication challenging between mothers and daughters? Journal of Family Communication, 10(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431003595496

Crohn, H. M. (2010). Communication about sexuality with mothers and stepmothers from the perspective of young adult daughters. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 51(6), 348–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502551003652108

Deutsch, A. R., & Crockett, L. J. (2016). Gender, generational status, and parent–adolescent sexual communication: Implications for Latino/a adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(2), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12192

Elliott, S. (2010). Talking to Teens about Sex: Mothers Negotiate Resistance, Discomfort, and Ambivalence. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7(4), 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0023-0

Finer, L. B., & Zolna, M. R. (2016). Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(9), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1506575

Fletcher, K. D., Ward, L. M., Thomas, K., Foust, M., Levin, D., & Trinh, S. (2015). Will it help? Identifying socialization discourses that promote sexual risk and sexual health among African American youth. Journal of Sex Research, 52(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.853724

Flores, D., & Barroso, J. (2017). 21st century parent–child sex communication in the United States: A process review. Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 532–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1267693

Fry, R., Passel, J. S., & Cohen, D. (2020). A majority of young adults in the U.S. live with their parents for the first time since the Great Depression. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/04/a-majority-of-young-adults-in-the-u-s-live-with-their-parents-for-the-first-time-since-the-great-depression/ Accessed 5th April 2021

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130905

Golish, T., & Caughlin, J. (2002). “I’d rather not talk about it”: Adolescents’ and young adults’ use of topic avoidance in stepfamilies. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 30(1), 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880216574

Grossman, J. M., Jenkins, L. J., & Richer, A. M. (2018). Parents' perspectives on family sexuality communication from middle school to high school. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010107

Grossman, J. M., Sarwar, P. F., Richer, A. M., & Erkut, S. (2017). “We talked about sex.” “No, wee didn’t”: Exploring adolescent and parent agreement about sexuality Communication. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 12(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2017.1372829

Grossman, J. M., Tracy, A. J., Charmaraman, L., Ceder, I., & Erkut, S. (2014). Protective effects of middle school comprehensive sex education with family involvement. The Journal of School Health, 84(11), 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12199

Grotevant, H. D., & Cooper, C. R. (1985). Patterns of interaction in family relationships and the development of identity exploration in adolescence. Child Development, 56(2), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129730

Guilamo-Ramos, V., Bouris, A., Lee, J., McCarthy, K., Michael, S. L., Pitt-Barnes, S., & Dittus, P. (2012). Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: A structured literature review. Pediatrics, 130(5), e1313–e1325. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2066

Gute, G., & Eshbaugh, E. M. (2008). Personality as a predictor of hooking up among college students. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 25(1), 26–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370010701836385

Heisler, J. M. (2014). They need to sow their wild oats: Mothers’ recalled memorable messages to their emerging adult children regarding sexuality and dating. Emerging Adulthood, 2(4), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814550196

Jonason, P. K., & Marks, M. J. (2009). Common vs. uncommon sexual acts: Evidence for the sexual double standard. Sex Roles, 60(5–6), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9542-z

Kirby, D. (2007). Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Retrieved from Washington, DC:

Koepke, S., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2012). Dynamics of identity development and separation–individuation in parent–child relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood –- A conceptual integration. Developmental Review, 32(1), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2012.01.001

Kuhle, B. X., Melzer, D. K., Cooper, C. A., Merkle, A. J., Pepe, N. A., Ribanovic, A., & Wettstein, T. L. (2015). The “birds and the bees” differ for boys and girls: Sex differences in the nature of sex talks. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000012

Lipstein, E. A., & Britto, M. T. (2015). Evolution of pediatric chronic disease treatment decisions: A qualitative, longitudinal view of parents’ decision-making process. Medical Decision Making, 35(6), 703–713.

Malacane, M., & Beckmeyer, J. J. (2016). A review of parent-based barriers to parent–adolescent communication about sex and sexuality: Implications for sex and family educators. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2016.1146187

Manago, A. M., Ward, L. M., & Aldana, A. (2015). The Sexual Experience of Latino Young Adults in College and Their Perceptions of Values About Sex Communicated by Their Parents and Friends. Emerging Adulthood, 3(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814536165

Marseille, E., Mirzazadeh, A., Biggs, M. A., Miller, P., & A., Horvath, H., Lightfoot, M. Kahn, J. G. (2018). Effectiveness of school-based teen pregnancy prevention programs in the USA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 19(4), 468–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0861-6

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

Morgan, E. M., Thorne, A., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2010). A longitudinal study of conversations with parents about sex and dating during college. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016931

Oswalt, S. B. (2010). Beyond risk: Examining college students’ sexual decision making. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 5(3), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2010.503859

Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2018). Longitudinal change in parent-adolescent communication about sexuality. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(6), 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.06.031

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Rogers, A. A., & McLean, R. D. (2020). Is there more than one way to talk about sex? A longitudinal growth mixture model of parent–adolescent sex communication. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(6), 851–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.031

Pariera, K. L., & Brody, E. (2018). “Talk more about it”: Emerging adults’ attitudes about how and when parents should talk about sex. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC, 15(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0314-9

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand

Pluhar, E., DiIorio, C. K., & McCarty, F. (2008). Correlates of sexuality communication among mothers and 6–12-year-old children. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 34(3), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00807.x

QSR International. (2012). NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software Version 10. QSR International.

Riggio, H. R., Galaz, B., Garcia, A. L., & Matthies, B. K. (2014). Contraceptive attitudes and sexual self-esteem among young adults: Communication and quality of relationships with mothers. International Journal of Sexual Health, 26(4), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2014.885924

Ritchwood, T. D., Powell, T. W., Metzger, I. W., Dave, G., Corbie-Smith, G., Atujuna, M., & Akers, A. Y. (2017). Understanding the Relationship between Religiosity and Caregiver-Adolescent Communication About Sex within African-American Families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(11), 2979–2989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0810-9

Santa Maria, D., Markham, C., Bluethmann, S., & Mullen, P. D. (2015). Parent-based adolescent sexual health interventions and effect on communication outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1363/47e2415

Secor-Turner, M., Sieving, R. E., Eisenberg, M. E., & Skay, C. (2011). Associations between sexually experienced adolescents’ sources of information about sex and sexual risk outcomes. Sex Education, 11(4), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2011.601137

Shtarkshall, R. A., Santelli, J. S., & Hirsch, J. S. (2007). Sex education and sexual socialization: Roles for educators and parents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(2), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1363/3911607

Tobey, J., Hillman, S. B., Anagurthi, C., & Somers, C. L. (2011). Demographic differences in adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behaviors, parent communication about sex, and school sex education. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 14, 1–12.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Talk to your kids about sex. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/everyday-healthy-living/sexual-health/talk-your-kids-about-sex#panel-1. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/everyday-healthy-living/sexual-health/talk-your-kids-about-sex#panel-1

Ward, L. M. (2003). Understanding the role of entertainment media in the sexual socialization of American youth: A review of empirical research. Developmental Review, 23, 347–388.

Widman, L., Choukas-Bradley, S., Helms, S. W., Golin, C. E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2013). Sexual The Journal of Sex Research, 51, 731–741. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.843148

Widman, L., Choukas-Bradley, S., Noar, S. M., Nesi, J., & Garrett, K. (2016). Parent-Adolescent Sexual Communication and Adolescent Safer Sex Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731

Wright, P. J. (2009). Father-child sexual communication in the United States: A review and synthesis. Journal of Family Communication, 9(4), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267430903221880

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: R03 HD095029 and by Wellesley Centers for Women. The authors are grateful for the families who were part of this project for many years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grossman, J.M., Richer, A.M. Parents’ Perspectives on Talk with Their Adolescent and Emerging Adult Children About Sex: a Longitudinal Analysis. Sex Res Soc Policy 20, 216–229 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00656-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00656-w