Abstract

Introduction

Studies examining why heteronormative beliefs shape the coming out process of sexual minority men are still scarce. This study aimed to examine whether heteronormative beliefs result in more internalized homonegativity and more sexual identity stigma. We also compared socio-cultural contexts—Portugal and Turkey—with distinct social policies toward sexual minority people. Lastly, we explored the correlates of coming out to friends and family members.

Methods

A cross-sectional study with 562 sexual minority men (93.4% cisgender; Mage = 26.69, SD = 9.59) from Portugal and Turkey was conducted between March and July 2019.

Results

Heteronormative beliefs were associated with increased internalized homonegativity and, in turn, with increased sexual identity stigma (identity stigma and social discomfort). This mediation was moderated by country, such that conditional direct effects were stronger among Turkish sexual minority men. Conditional indirect effects, however, were stronger among Portuguese sexual minority men. Furthermore, less internalized homonegativity and less social discomfort were associated with coming out to friends and family members in different ways.

Conclusions

This study contributed to the understanding of sexual identity development and acceptance among sexual minority men in two distinct socio-cultural contexts. Findings showed that the internalization of heteronormative beliefs was associated with identity stigma and highlighted the role of socialization in these processes.

Policy Implications

For people working with sexual minority men from diverse socio-cultural contexts, our findings can offer new insights on how to offer the best help in the coming out process of these sexual minority men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The process of sexual identity development in sexual minority people (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual) is complex and entails the experience of cognitive incongruence between expected heterosexuality and the experience of same-sex sexual and romantic feelings (Cass, 1979). This process is often associated with poorer psychological and physical outcomes, such that people who struggle with their sexual identity are at higher risk of developing depressive symptoms later on (Everett, 2015). When people are able to resolve such incongruity, they are more likely to accept their sexual identity and—to some extent—disclose it to others (D’Augelli, 1994; Manning, 2015; Rosario et al., 2001).

The coming out process can have several psychological benefits, including increased self-esteem and sense of belonging, decreased minority stress and psychological distress, and better overall mental health (e.g., Bybee et al., 2009; Meyer, 2013; Morris, 2001; Rosario et al., 2001). However, it can also be associated with negative psychological and physical outcomes, especially when people experience negative reactions or lack of support from their close social network (e.g., Goldbach et al., 2014; Ryan et al., 2015). For example, Legate et al. (2011) showed that sexual minority people were less open about their sexual identity and experienced more anger and less self-esteem in contexts with low autonomy support (e.g., religious community), when compared to contexts with high autonomy support (e.g., friends). There is also evidence that sexual minority people who go through the coming out process in heteronormative socio-cultural contexts experience greater isolation, stigmatization, and violence (Martin & Hetrick, 1988). For example, Wagner et al. (2013) found that sexual minority men who experienced social hostility (e.g., verbal harassment) were less comfortable with their identity, and more likely to develop coping mechanisms (e.g., social avoidance) to limit their exposure to stigma. Arguably, sexual minority people in heteronormative societies integrate negative societal views about sexuality as part of their sexual identity (Berg et al., 2016) and experience greater internalized homonegativity (Herek, 2004). In turn, internalized homonegativity emphasizes negative evaluations and stereotypes about gender. For example, López-Sáez et al. (2020) found that gay men who expressed greater discomfort with their sexuality also reported greater ambivalent sexism. Equally important, internalized homonegativity has been construed as a proximal stressor associated with poorer psychological health and well-being (e.g., Meyer, 2013). Hence, in this study, we examined if heteronormative beliefs—resulting from socially imposed heteronormativity—were associated with sexual identity stigma in sexual minority men and if this association was explained by their internalized homonegativity. We also explored the extent to which these variables were associated with the disclosure of sexual identity to friends and family. To have a more comprehensive understanding of these phenomena, we compared two socio-cultural contexts—Portugal and Turkey—that have distinct social and legal perspectives on same-sex relationships (e.g., Carrol & Mendos, 2017; Costa, 2021), different levels of internalized homophobia (Berg et al., 2013) and different attitudes toward homosexuality and same-sex relationships (Costa et al., 2018; O’Neil & Çarkoğlu, 2020; Pew Research Center, 2020).

Heteronormativity and the Coming Out Process

Heteronormativity refers to a political, social, philosophical, and economic regime that imposes specific gender roles, sexual behaviors, and sexual orientation (e.g., through laws, religion, education, family) to conform with heterosexuality, and with how men and women should behave (Habarth, 2015; Kitzinger, 2005; Nielsen et al., 2000). This norm conveys the notion that heterosexuality is superior to other sexual identities (Eguchi, 2009; Elia, 2003; Habarth, 2015), rendering sexual minority people at risk for stigmatization and violence. Indeed, these people report being victims of physical and verbal harassment, property crime, and employment or housing discrimination (e.g., Drydakis, 2015; Herek, 2009; Swank et al., 2013). For example, heterosexual people are less likely to recommend gay-sounding men for typically masculine job positions (e.g., leadership; Fasoli et al., 2017). These people are also stigmatized by political structures. For example, Arreola et al. (2015) found higher levels of sexual identity stigma in countries that criminalize same-sex behaviors. In this sense, heteronormativity influences and justifies the assumptions of homonegativity.

Heteronormativity shapes not only the identity and behaviors of heterosexual people but also how sexual minority people construe their sexual identity and coming out. Indeed, the coming out process can be influenced by a myriad of values, including societal norms and public policies, and more particularly individual values and religious beliefs (Mohr & Fassinger, 2003; Shapiro et al., 2010). For example, Gough (2007) showed that gay male athletes were more likely to embrace typically masculine behaviors to avoid disclosing their sexual identity because they feared the negative consequences of coming out in a typically hypermasculine context. Similarly, Gottschalk and Newton (2009) found that sexual minority people living in conservative rural contexts were less likely to disclose their sexual orientation, to avoid stigmatization and prejudice. In contrast, Toomey et al. (2012) found that sexual minority students perceived more safety when their schools engaged in policies to reduce heteronormativity. Similarly, Bauermeister et al. (2010) found that sexual minority people were more comfortable with exploring their sexual identity in contexts that supported non-conforming sexual identities.

Theoretical models focusing on the coming out process define self-acceptance as the process whereby people embrace their non-heterosexual identity as part of the self (e.g., Bilodeau & Renn, 2005; Fassinger & Miller, 1997), and disclosure as the process whereby people openly share their sexual identity with others (e.g., Collins & Miller, 1994; Mohr & Fassinger, 2003). Both processes are interrelated, albeit not simultaneous, and can mutually influence each other (McCarn & Fassinger, 1996). Studies typically examine if and why heteronormativity acts as an external force (e.g., heteronormative contexts) in the coming out process. We focused instead on the psychological internalization of social heteronormativity (Crocker et al., 1998).

Heteronormativity Beliefs and Internalized Homonegativity

People are continuously exposed through institutions (e.g., school, family, religion) to heterosexist beliefs (e.g., Jackson, 2006; Nielsen et al., 2000; Seidman, 2009). This likely results in internalized homonegativity, that is, negative attitudes and stigmatization of others solely based on their sexual identity (Habarth, 2015; Herek, 2000; T. G. Morrison et al., 1999). To sexual minority people, internalized homonegativity conflicts with the self-acceptance and disclosure of their sexual identity. According to the minority stress model (Meyer, 1995, 2013), internalized homonegativity can be associated with poorer mental outcomes, such as negative feelings toward one’s sexual identity and discrimination of non-heterosexual people (Herek, 2004), anxiety and depression (Lorenzi et al., 2015), and social anxiety (Lingiardi et al., 2012). These correlates were found to be cross-culturally robust (Sattler & Lemke, 2019). For example, Feinstein et al. (2012) found that sexual minority people who were stigmatized by others and their society reported more social anxiety and depressive symptoms. This occurred, at least in part, because sexual minority people had more internalized homonegativity, and therefore felt worse about themselves and their sexual identity. Internalized homonegativity was also one of the reasons why sexual identity discrimination is related to less subjective well-being (Conlin et al., 2019; Walch et al., 2016). This can have implications for physical health, such that people with more internalized homonegativity were more likely to have been diagnosed with sexually transmitted infections and to report substance abuse (Andrinopoulos et al., 2015; Berg et al., 2015), and are likely to perceive more stress one year later (Tatum & Ross, 2020). Internalized homonegativity can also shape interpersonal experiences. For example, people with more internalized homonegativity have exaggerated gender role performances (Eguchi, 2009) and engage in typically masculine behaviors (Herek et al., 2007), arguably to avoid being discriminated against by others. As such, sexual minority men with more heteronormative beliefs should have more internalized homonegativity, and in turn, report more sexual identity stigma. More broadly, these variables should also be associated with the likelihood of having disclosed one’s sexual identity to friends and family (e.g., Camacho et al., 2020).

Socio-cultural Differences in the Experiences of Sexual Minority Men

Research has shown higher levels of internalized homonegativity in more conservative socio-cultural contexts and lower levels of sexual identity stigma in more inclusive socio-cultural contexts (e.g., Brown et al., 2016; Herek et al., 2015; Riggle et al., 2017; Tran et al., 2018). Hence, a more comprehensive understating of sexual identity stigma and coming out of sexual minority men should examine socio-cultural differences, particularly in contexts typically underrepresented in the literature. Our research was focused on two countries—Portugal and Turkey—that have different approaches to the sexual minority community. Portugal has inclusive social policies and laws for sexual minority people, such that the Portuguese legal framework has laws against discrimination based on sexual identity since 2005, recognized same-sex unions in 2001, legalized same-sex marriage in 2010, and allows same-sex couples to adopt since 2016 (Carrol & Mendos, 2017; Costa, 2021). Despite not criminalizing same-sex behaviors, Turkey does not have socially inclusive policies or protection laws against sexual identity discrimination and does not recognize same-sex marriage (Carrol & Mendos, 2017; Engin, 2015). The way with which heteronormative beliefs are conveyed in both countries is also different. In Portugal, the disapproval of current inclusive policies mainly comes from opposing far-rights political parties and members of the Catholic Church (Brandão & Machado, 2012; Oliveira et al., 2013), although some degree of sexual discrimination is still observed in society. For example, results from the Eurobarometer on Discrimination (European Commission, 2019) showed that 71% of Portuguese people consider sexual identity discrimination to be a common practice in their country, but 78% would be comfortable with having a sexual minority person as a coworker and 50% would be comfortable with having their children be in a same-sex romantic relationship. In another study, Costa et al. (2018) found that most Portuguese people were supportive or extremely supportive of same-sex marriage (78%) and parenting (68%). Contrasting with these findings, results from the Public Perceptions of Gender Roles Survey in Turkey (O’Neil & Çarkoğlu, 2020) showed that 77% of Turkish people considered same-sex relationships to be against the social norm and 55% considered that sexual minority people should not have access to equal rights. In another study, results showed that only 25% of Turkish people believe that homosexuality should be accepted by society, contrasting with an average of 87% reported by some Western European counties (Pew Research Center, 2020). Unsurprisingly, then, research has shown that sexual minority Turkish people tend to engage in different identity concealment strategies to avoid being discriminated against (Bakacak & Ōktem, 2014; Ikizer et al., 2018).

Overview and Hypotheses

Most studies focus on the consequences of socially imposed heteronormativity on the mental health of sexual minority people (Herek et al., 2007; Meyer, 1995, 2013). Yet, research examining the role of the heteronormative beliefs—internalized through socialization—on the coming out process of sexual minority men is still scarce. We focused on this sample because previous research suggested that men tend to be more affected by heteronormative beliefs than women. For example, Eguchi (2009) showed that gay men tend to be more pressured to conform to masculine heteronormative roles, which arguably explains why they tend to engage in typically masculine behaviors in more conservative contexts. Moreover, sexual minority men also tend to report high levels of sexual identity stigma (Lingiardi et al., 2012). We also extended the literature by comparing two distinct and underrepresented socio-cultural contexts—Portugal and Turkey—that differ in heteronormative beliefs and social policies toward sexual minorities (Carrol & Mendos, 2017).

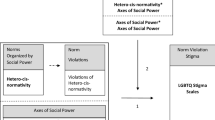

The coming out process results from a balance between heteronormative beliefs and sexual identity (Fassinger & Miller, 1997; Habarth, 2015). Hence, sexual minority men with more heteronormative beliefs should report more sexual identity stigma—more identity stigma and more social discomfort with their sexual identity (Hypothesis 1). The constant exposure to heteronormative values conveyed by society (Nielsen et al., 2000; Seidman, 2009) results in negative views and prejudice toward sexual minority people (Habarth, 2015; Herek, 2000; T. G. Morrison et al., 1999), which conflicts with a sexual minority identity and likely results in stigmatization. Based on this reasoning, we expected heteronormative beliefs to be positively associated with internalized homonegativity (Hypothesis 2). However, heteronormative beliefs and internalized homonegativity differ between socio-cultural contexts (Brown et al., 2016; Riggle et al., 2017; Tran et al., 2018), such that Portugal has more inclusive social policies and laws than Turkey (e.g., Costa, 2021; European Commission, 2019; O’Neil & Çarkoğlu, 2020). As such, we expected heteronormative beliefs to have stronger positive associations with identity stigma (Hypothesis 3) and internalized homonegativity (Hypothesis 4) among Turkish (vs. Portuguese) sexual minority men. Lastly, we expected internalized homonegativity to explain the association between heteronormative beliefs and sexual identity stigma, particularly among Turkish (vs. Portuguese) sexual minority men (Hypothesis 5). The hypothesized moderated mediation model is depicted in Fig. 1.

Lastly, there is a dearth of research examining the correlates of coming out among Portuguese and Turkish sexual minority men. As such, we explored the extent to which heteronormative beliefs, internalized homonegativity, and sexual identity stigma were associated with the likelihood of having disclosed one’s sexual orientation to friends and family. Given their role in the coming out process, we controlled for age, sexual orientation, relationship status, political orientation, and religiosity in all analyses (e.g., Barnes & Meyer, 2012; Crawford & Pilanski, 2014; Dyar et al., 2019; Hooghe et al., 2010; M. A. Morrison & Morrison, 2003; Pacilli et al., 2011; Pistella et al., 2016; Rosario et al., 2001; Ross et al., 2018; Taggart et al., 2019).

Method

Participants

A total of 952 people assessed the survey and 337 abandoned before survey completion. From the eligible sample, we removed participants who identified themselves as women or transgender women (n = 22), and those with missing values in all of our main measures (n = 31). The final sample included 562 sexual minority men (93.4% cisgender) with ages ranging from 18 to 67 (M = 26.69, SD = 9.59). All participants indicated to be sexually and/or romantically attracted to other men, most identified themselves as gay (76.2%), were single (61.9%), had center-left or left political orientations (68.5%), and never attended religious services (50.3%). Country comparisons further showed that Portuguese sexual minority men were more likely to be older, to identify themselves as gay, to be dating or to have a domestic partnership, to have center-right or center-left political orientations, and to attend religious services on special occasions, whereas Turkish minority men were more likely to be younger, to identify with other sexual orientations (e.g., pansexual, asexual, queer), to be single, to have a left political orientation, and to never attend religious services, all ps < .050 (see Table 1 for details).

Measures

Heteronormative Beliefs

We used the Normative Behavior subscale of the Heteronormative Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (Habarth, 2015). Participants were asked to indicate the extent with which they agree or disagree (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree) with eight items, assessing typical gender role expectations in relationships (e.g., “Things go better in intimate relationships if people act according to what is traditionally expected of their gender”). We computed a single index by averaging responses across all items (Portugal: α = .62, Turkey: α = .72), with higher scores indicating more heteronormative beliefs.

Internalized Homonegativity

We used the Modern Homonegativity Scale (Morrison & Morrison, 2003) to assess modern prejudice toward sexual minority people. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree) with 12 items (e.g., “Many gay men use their sexual orientation so that they can obtain special privileges”). One item was modified to fit other socio-cultural contexts (i.e., we rephrased “Canadians’ tax dollars…” to “Taxes…”). We computed a single index by averaging responses across all items (Portugal: α = .89, Turkey: α = .80), with higher scores indicating more internalized homonegativity.

Sexual Identity Stigma

We used two subscales of the Measure of Internalized Sexual Stigma for Gay Men (Lingiardi et al., 2012) to assess negative attitudes sexual minority men hold about their sexual orientation. The Identity stigma subscale (five items; Portugal: α = .74, Turkey: α = .79) assesses negative self-attitudes sexual minority men have about their sexuality and the internalization of sexual stigma as part of the identity (e.g., “Sometimes I think that if I were heterosexual, I could be happier”). The Social discomfort subscale (seven items; Portugal: α = .86, Turkey: α = .84) assesses the fear of public identification as a sexual minority man in social contexts and the fear of disclosure in social spheres (e.g., “I am careful of what I wear and what I say to avoid showing my homosexuality”). Participants were asked to what extent they agree or disagree with each item on a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree). We computed indexes for each subscale by averaging responses, with higher scores indicating more identity stigma and more social discomfort.

Political Orientation and Religiosity

We used two single-item measures to assess political orientation and religiosity (Morrison & Morrison, 2003). Participants were asked to indicate their political orientation (e.g., 1 = Right, 2 = Center-right, 3 = Center, 4 = Center-left, 5 = Left) and the frequency with which they attend to religious services (1 = Never, 2 = On special occasions, 3 = Now and then, 4 = Usually).

Procedure

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Iscte-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ref.: 11/2019) before data collection. An online survey hosted on Qualtrics was available in Portuguese, Turkish, and English, between March and July 2019. The study protocol was the same in both countries and participants could select the language best suited to them. To recruit participants, we advertised the study in LGBTI + oriented Facebook groups and in gay dating apps (e.g., Grindr), used Instagram ads, and asked LGBTI + NGOs from both countries to share the survey in their social media and among their members.

Before starting, people were told that they would be taking part in a study examining their ideas on sexual orientation, gender roles, and relational behaviors. To participate, people had to be Portuguese or Turkish (or at least live in those countries), to have 18 years or older, to identify themselves as men, and to be sexually/romantically attracted to other men. Lastly, they were informed that participation was anonymous and voluntary, that participants had the right to skip or omit any questions or abandon the survey at any time. After providing written informed consent (clicking in the yes option), participants were asked to provide demographic information (e.g., nationality, country of residence, age, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, relationship status) and to indicate if they came out to friends (No/Yes) and family members (No/Yes). This was followed by the main measures. Throughout the survey, participants were free to skip or omit their answers, i.e., they were reminded of any missed questions in the survey but allowed to continue. Upon completion, participants were informed that the study aimed to understand the role of heteronormative beliefs on self-accepting and disclosing one’s sexual orientation, and provided contact information of the main researcher. The mean completion time for the survey was 17 min.

Data Analysis

We first present overall descriptive statistics in our main measures, compared both countries using t tests, and overall correlations between the measures. We then test our theoretical model. We expected heteronormative beliefs to be positively associated with sexual identity stigma (Hypothesis 1) and with internalized homonegativity (Hypothesis 2). We also expected both associations to be moderated by country, such that heteronormative beliefs should have stronger associations with sexual identity stigma (Hypothesis 3) and internalized homonegativity (Hypothesis 4) for Turkish (vs. Portuguese) sexual minority men. Lastly, we expected internalized homonegativity to mediate the association between heteronormative beliefs and identity stigma, especially among Turkish (vs. Portuguese) sexual minority men (Hypothesis 5). We computed two 10,000 bootstrapped moderated mediation models using PROCESS 3.4 for SPSS (Model 8; Hayes, 2017). In both models, heteronormative beliefs were the predictor (X), internalized homonegativity was the mediator (M), and country (− 1 = Portugal; + 1 = Turkey) was the moderator (W). Variables that defined products were mean-centered before the analyses. Identity stigma (Y1) and social discomfort (Y2) were the different outcomes. In both analyses, age, sexual orientation, relationship status, political orientation, and religiosity were entered as covariates (see also Table 1). Lastly, we explored the correlates of coming out to friends and family (− 1 = No; + 1 = Yes) by computing two binary logistic regressions. Country, age, sexual orientation, relationship status, political orientation, and religiosity were entered in Step 1, and heteronormative beliefs, internalized homonegativity, identity stigma, and social discomfort were entered in Step 2.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

As shown in Table 2, Turkish (vs. Portuguese) sexual minority men reported more heteronormative beliefs, p < .001, more homonegativity, p < .001, more identity stigma, p < .001, and more social discomfort, p < .001. We also found significant positive correlations between all measures, all ps < .001. For example, sexual minority men with more heteronormative beliefs also reported more internalized homonegativity, more identity stigma, and more social discomfort.

Main Analysis

Results of the moderated mediation models are summarized in Table 3. As expected, heteronormative beliefs were positively associated with identity stigma, p < .001, and social discomfort, p < .001 (Hypothesis 1). However, the expected interaction with country was only observed in Model B, p = .034 (Hypothesis 3), such that the positive association between heteronormative beliefs and social discomfort was significant for Turkish sexual minority men, p < .001, but not for Portuguese sexual minority men, p = .074 (Fig. 2).

Results also showed the expected positive association between heteronormative beliefs and internalized homonegativity, p < .001 (Hypothesis 2). Although this interaction was moderated by country, p = .002 (Hypothesis 4), we found significant associations for Turkish, p < .001, and Portuguese men, p < .001 (Fig. 3). On a closer inspection of the associations in each country, contrast analyses showed that Portuguese sexual minority men with less heteronormative beliefs (− 1 SD) reported less internalized homonegativity than Turkish sexual minority men, t(463) = 4.56, p < .001, whereas no differences emerged among Portuguese and Turkish men with more heteronormative beliefs (+ 1 SD), t < 1.

Lastly, results showed that internalized homonegativity was positively associated with identity stigma, p = .004, and social discomfort, p < .001. As expected (Hypothesis 5), conditional direct effects were stronger for Turkish sexual minority men. However, indexes of moderated mediation showed stronger indirect effects for Portuguese sexual minority men (see Table 4).

Coming Out to Friends and Family

Considering the overall sample, results showed that most participants made their coming out to friends (87.3%), and this was particularly evident among Portuguese (91.3% vs. Turkish: 81.0%) sexual minority men, χ2 (1) = 11.62, p = .001, V = .15. In contrast, only about half of the overall sample disclosed their sexual orientation to family members (51.7%). Again, such disclosure was more likely among Portuguese (65.1% vs. Turkish: 30.7%) sexual minority men, χ2 (1) = 61.54, p < 0.001, V = .34.

Results of the logistic regressions are summarized in Table 5. Disclosing one’s sexual orientation to friends was more likely among younger sexual minority men, p = .001, those identifying as gay, p < .001, those with less internalized homonegativity, p = .026, and those with less social discomfort, p < .001. Disclosing one’s sexual orientation to family members, on the other hand, was more likely among Portuguese men, p < .001, those identifying as gay, p = .032, those in a relationship, p = 0.010, and those with less social discomfort, p < .001.

Discussion

Building upon the Stress Minority Model (Meyer, 2013), we examined if socially imposed heteronormative beliefs were associated with minority identity (i.e., sexual identity stigma), because sexual minority men experience more proximal minority stress processes (i.e., internalized homonegativity). The study also accounted for socio-cultural contextual differences, by examining if this process differed between Portuguese and Turkish sexual minority men. Lastly, the study examined the correlates of having disclosed one’s sexual orientation to friends and family. Results generally supported our hypotheses, such that heteronormative beliefs were associated with more identity stigma and more social discomfort, and internalized homonegativity explained these associations. As heteronormative values regulate gender roles (Habarth, 2015; Jackson, 2006; Kitzinger, 2005; López-Sáez et al., 2020; Nielsen et al., 2000; Seidman, 2009), the internalization of such norms implies the stigmatization of non-conforming sexual identities and the development of negative attitudes toward people from sexual minorities (Herek, 2004). Faced with internalized homonegativity, sexual minority men have more difficulties in sexual identity development and experience more identity stigma and social discomfort.

These experiences should be particularly evident in socio-cultural contexts in which heteronormativity is endorsed and, consequently, internalized homonegativity is reinforced (for a discussion, see Herek et al., 2015). And yet, our results showed that Portuguese and Turkish sexual minority men have different coming out experiences. Portuguese (vs. Turkish) men reported less heteronormative beliefs, internalized homonegativity, identity stigma, and social discomfort. This is aligned with past evidence showing that contexts with more supportive and inclusive policies—like the Portuguese context—can help sexual minority people develop their sexual identity (e.g., Bauermeister et al., 2010; Toomey et al., 2012), which can benefit the coming out process. We also found that heteronormative beliefs were associated with more identity stigma in both countries—albeit stronger among Turkish sexual minority men—and only with more social discomfort among Turkish sexual minority men. This resulted in stronger direct effects in this sample. These findings may be explained by the fact that identity stigma is a predisposition to consider sexual identity stigma as part of society's values (Lingiardi et al., 2012). To the extent that Portuguese and Turkish minority men acknowledge the existence of sexual identity stigma in their socio-cultural contexts (European Commission, 2019; O’Neil & Çarkoğlu, 2020), it is not surprising that socially imposed heteronormative beliefs shape the stigma sexual minority men experience with their own sexual identity. However, because Portuguese sexual minority men also acknowledge they would accept having a sexual minority person in their immediate social network (European Commission, 2019) and are more accepting of same-sex marriage and parenting (Costa et al., 2018), sexual minority men in this socio-cultural context may be more comfortable with expressing their sexual identity in social contexts, and less restrained by heteronormative social impositions. The opposing reasoning would be applied to the Turkish context (e.g., O’Neil & Çarkoğlu, 2020; Pew Research Center, 2020), which could explain why Turkish sexual minority men tend to conceal their sexual identity (Bakacak & Ōktem, 2014; Ikizer et al., 2018). Our results also showed country differences in the association between heteronormative beliefs and internalized homonegativity. Against our expectations, we found a stronger (rather than weaker) association in the Portuguese sample. A closer inspection of the slopes, however, showed that Portuguese sexual minority men who endorsed less heteronormative beliefs also had significantly less internalized homonegativity, whereas that was not the case with Turkish sexual minority men. In contrast, sexual minority men who endorsed more heteronormative beliefs also had significantly more internalized homonegativity, regardless of their socio-cultural context. As a consequence of these findings, indirect effects were stronger among Portuguese sexual minority men. A possible explanation for the steeper slope in the Portuguese sample could be taken from Oliveira et al. (2013). The authors suggested that Portuguese political strategies for sexual minority inclusion continue to be influenced by historical events and discourses that sustain strong heteronormative values (e.g., the persistence of Catholic morality, the Estado Novo regime). The authors also argued that heteronormativity values are still embedded in inclusive policies, because sexual minority inclusion is still somewhat dependent on how heteronormatively sexual minority people behave. For example, heteronormativity values regulate gender roles and sexual behavior by imposing the idea that sexual minority people are accepted insofar they comply with family-oriented values (Seidman, 2005). Aligned with this argument, Rodrigues et al. (2018) found no evidence of stigmatization when different-sex and same-sex romantic partners were in a committed monogamous relationship. In their analysis of the Portuguese context, Oliveira et al. (2013) further argued that some sexual minority groups and sexual minority people embraced this compliance idea to increase visibility, ensure safety, decrease discrimination and promote inclusive policies. The internalization of this dichotomy as part of the heteronormative beliefs system may explain who sexual minority people have internalized homonegativity toward others who do not comply with societal values, fit in society, or need to constantly draw attention to their sexual identity (Morrison & Morrison, 2003).

Examining the correlates of the coming out process, our results also showed clear country differences. We found that Portuguese and Turkish sexual minority men were likely to have disclosed their sexual orientation to friends—but even more so in the Portuguese sample. However, Portuguese sexual minority men were more likely to have disclosed their sexual orientation to family members, whereas only one third of the Turkish sexual minority men were likely to have done so. Again, these results reflect the socio-cultural differences between Portugal and Turkey, and how these differences shape the likelihood of coming out to close others. Our exploratory results further showed that identifying as a sexual minority and being more socially comfortable with one’s sexual identity increased the likelihood of making one’s coming out to friends and family (see also Rosario et al., 2006). There were also specific correlates of coming out, such that being younger and having less internalized homonegativity were associated with coming out to friends, whereas having a romantic relationship was associated with coming out to family members. These findings suggest that coming out is experienced differently depending on the source of social support. To the extent that friends are often a source of emotional support and identification during identity development (e.g., Barry et al., 2016; Helsen et al., 2000; Rodrigues et al., 2017), a similar process might also occur in the development of sexual identity (e.g., Elizur & Ziv, 2001; Maguen et al., 2002). In this sense, younger sexual minority men might be more comfortable with disclosing their sexual identity to friends with whom they share a sense of belonging. In contrast, sexual minority men may be more comfortable disclosing their sexual identity to family members when they have emotional support from an intimate romantic partner (e.g., Martos et al., 2015; Pistella et al., 2016; Rodrigues, Huic, et al., 2019; Rodrigues, Lopes, et al., 2019; Rodrigues, Lopes, et al., 2019).

Limitations and Future Research

We must acknowledge some limitations to our study. First, our study does not allow us to establish causality between our variables. Nonetheless, it seems more likely that heteronormative beliefs become internalized through socialization and causes sexual minority people to develop homonegativity, rather than the other way around. Still, future research should seek to develop cross-cultural longitudinal studies to understand if heteronormative beliefs indeed predict the coming out process in different socio-cultural contexts and whether these temporal effects are explained by the levels of internalized homonegativity. Second, we did not measure relevant variables that could further moderate our findings or have implications for interpersonal processes. For example, internalized homonegativity has been associated with identity concealment (Gonçalves et al., 2020), dissatisfaction with sex life (Berg et al., 2015), less quality in romantic relationships (Doyle & Molix, 2015; Rostosky & Riggle, 2017), and less emotional intimacy with the romantic partner (Šević et al., 2016; Thies et al., 2016). To the extent that romantic partners, friends, and parents are important sources of emotional support to sexual minority people (e.g., Bauermeister et al., 2010; Doty et al., 2010; Friedman & Morgan, 2009; Rodrigues, Huic, et al., 2019; Rodrigues, Lopes, et al., 2019; Rothman et al., 2012; Whitton et al., 2018), future research should examine if such sources of support moderate some of our findings and their implications for interpersonal relationships and individual well-being. Future research should also seek to further understand the coming out process by using more detailed measures of coming out (e.g., breadth and depth of disclose in the social network) and the engagement in strategies to conceal one’s sexual identity from others, and include other relevant measures to assess prejudice and discrimination (e.g., polymorphous prejudice; Lopes et al., 2017).

Lastly, our sample was recruited from Portuguese and Turkish LGBTI + organizations, internet ads in social media, groups on the internet and dating apps targeting gay men, and flyers in gay venues. This particular strategy of recruitment has some limitations in itself, and may limit the generalizability of our findings to sexual minority men that are less involved with the LGBTI + community, or less knowledgeable about LGBTI + culture. Although we acknowledge the difficulties to collect data with reserved (e.g., closeted) sexual minority men, researchers should seek to collect data from these men to have a broader understanding of how internalized socio-cultural values shape the socialization, identity development, and coming out (or lack thereof) of these men.

Social and Policy Implications

Our study contributes to the existing knowledge about sexual identity. Some models of sexual identity development (e.g., Cass, 1979; Fassinger & Miller, 1997) suggest that sexual minority people experience a phase of identity confusion, defined by the feelings of being different, sexual identity confusion, anxiety, and fear. Our findings suggest that this phase could be fostered by the contradiction between one’s feelings and socially imposed heteronormativity. As identity confusion is the result of sexual minority people feeling they are different because they do not share a heterosexual identity, having non-heterosexuality as a socially valid identity would likely reduce the emotional turmoil of accepting one’s sexual identity. Therefore, to decrease or end the struggles of sexual minority people during their coming out process, heteronormative beliefs imposed by socio-cultural traditions and social institutions (e.g., family, education, neighborhood, religion) should be openly discussed and revised by educators, support providers, opinion leaders, and policymakers to promote sexual diversity in society and more inclusive policies against discrimination, and consequently promote psychological health and well-being (see also Pachankis et al., 2015, 2020; Pachankis & Bränström, 2019).

Our findings can also be relevant to gay affirmative therapy and LGBTI + activism, by offering a new view on how to understand the difficulties sexual minority men experience with self-hate, internalized homonegativity, and lack of connectedness with the LGBTI + community. According to Meyer (1995, 2013), sexual minority people can experience decreased levels of minority stress when they get actively involved with LGBTI + communities because these people stop evaluating themselves in comparison to members of the dominant heteronormative culture. Nonetheless, even after sexual minority people assumed their sexual identity, many of them still struggle with internalized homonegativity. Therefore, and based on our findings, to successfully tackle the issues that compromise the development of sexual identity and the coming out of men, it is crucial to deconstruct the heteronormative beliefs they have internalized. This is consistent with the reasoning of D’Augelli (1994), suggesting that sexual minority people must become aware and demystify internalized stereotypical preconceptions about non-heterosexuals in the development of their sexual identity. This is crucial to reduce the importance of heteronormative beliefs to the internalization of homonegativity and sexual identity stigma and to destigmatize their feelings, experiences, and behaviors. For example, different support groups (e.g., ONGs, associations, online forums) could strive to develop evidence-based awareness campaigns and interventions targeted not only at LGBTI + people of different ages but also at members of close networks (e.g., friends, family) outside the LGBTI + community. Indeed, perceived social support from close networks and identification with the LGBTI + community are positively associated with sexual identity acceptance and psychological well-being (e.g., Brandon-Friedman & Kim, 2016; Snapp et al., 2015). These efforts would help people challenge their heteronormative beliefs, and question their views about gender identity, sexual behavior, sexual orientation, and consequently promote inclusion and acceptance. For sexual minority people, it would also help them accept and be comfortable with their sexual identity, therefore aiding in the coming out process and promote well-being. Lastly, the particular ways heteronormative beliefs are conveyed in different socio-cultural contexts must also be considered. Based on our findings, campaigns and interventions would likely be more beneficial in hostile environments (e.g., Turkey; Engin, 2015), even though specific needs must also be considered even in more inclusive environments (e.g., older gay men in Portugal; Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al., 2021).

Availability of Data and Material

The data and materials used in the research are available and can be obtained via email from the corresponding author.

References

Andrinopoulos, K., Hembling, J., Guardado, M. E., de Maria Hernández, F., Nieto, A. I., & Melendez, G. (2015). Evidence of the negative effect of sexual minority stigma on HIV testing among MSM and transgender women in San Salvador. El Salvador. AIDS and Behavior, 19(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0813-0

Arreola, S., Santos, G. M., Beck, J., Sundararaj, M., Wilson, P. A., Hebert, P., et al. (2015). Sexual stigma, criminalization, investment, and access to HIV services among men who have sex with men worldwide. AIDS and Behavior, 19(2), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0869-x

Bakacak, A. G., & Ōktem, P. (2014). Homosexuality in Turkey: Strategies for managing heterosexism. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(6), 817–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.870453

Barnes, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2012). Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01185.x

Barry, C. M., Madsen, S. D., & DeGrace, A. (2016). Growing up with a little help from their friends in emerging adulthood. In The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood (pp. 215–229). Oxford University Press.

Bauermeister, J. A., Johns, M. M., Sandfort, T. G. M., Eisenberg, A., Grossman, A. H., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2010). Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1148–1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y

Berg, R. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., & Ross, M. W. (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(4), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788

Berg, R. C., Ross, M. W., Weatherburn, P., & Schmidt, A. J. (2013). Structural and environmental factors are associated with internalised homonegativity in men who have sex with men: Findings from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS) in 38 countries. Social Science & Medicine, 78, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.033

Berg, R. C., Weatherburn, P., Ross, M. W., & Schmidt, A. J. (2015). The relationship of internalized homonegativity to sexual health and well-being among men in 38 European countries who have sex with men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 19(3), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2015.1024375

Bilodeau, B. L., & Renn, K. A. (2005). Analysis of LGBT identity development models and implications for practice. New Directions for Student Services, 2005(111), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.171

Brandão, A. M., & Machado, T. C. (2012). How equal is equality? Discussions about same-sex marriage in Portugal. Sexualities, 15, 662–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460712446274

Brandon-Friedman, R. A., & Kim, H.-W. (2016). Using social support levels to predict sexual identity development among college students who identify as a sexual minority. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 28(4), 292–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2016.1221784

Brown, J., Low, W. Y., Tai, R., & Tong, W. T. (2016). Shame, internalized homonegativity, and religiosity: A comparison of the stigmatization associated with minority stress with gay men in Australia and Malaysia. International Journal of Sexual Health, 28(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2015.1068902

Bybee, J. A., Sullivan, E. L., Zielonka, E., & Moes, E. (2009). Are gay men in worse mental health than heterosexual men? The role of age, shame and guilt, and coming-out. Journal of Adult Development, 16(3), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9059-x

Camacho, G., Reinka, M. A., & Quinn, D. M. (2020). Disclosure and concealment of stigmatized identities. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.031

Carrol, A., & Mendos, L. R. (2017). State-Sponsored Homophobia 2017: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition. ILGA. https://www.ilga.org/state-sponsored-homophobia-repor

Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01

Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.457

Conlin, S. E., Douglass, R. P., & Ouch, S. (2019). Discrimination, subjective wellbeing, and the role of gender: A mediation model of LGB minority stress. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(2), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1398023

Costa, P. A. (2021). Attitudes toward LGB families: International policies and LGB family planning. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1177

Costa, P. A., Carneiro, F. A., Esposito, F., D’Amore, S., & Green, R.-J. (2018). Sexual prejudice in Portugal: Results from the first wave European study on heterosexual’s attitudes toward same-gender marriage and parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0292-y

Crawford, J. T., & Pilanski, J. M. (2014). Political intolerance, right and left. Political Psychology, 35(6), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00926.x

Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998). Social stigma. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 504–553). McGraw-Hill.

D’Augelli, A. R. (1994). Identity development and sexual orientation: Toward a model of lesbian, gay, and bisexual development. In E. Trickett, R. Watts, & D. Birman (Eds.), Human Diversity: Perspectives on People in Context (pp. 312–333). Jossey-Bass Inc.

Doty, N. D., Willoughby, B. L. B., Lindahl, K. M., & Malik, N. M. (2010). Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1134–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x

Doyle, D. M., & Molix, L. (2015). Social stigma and sexual minorities’ romantic relationship functioning: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(10), 1363–1381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215594592

Drydakis, N. (2015). Sexual orientation discrimination in the United Kingdom’s labour market: A field experiment. Human Relations, 68(11), 1769–1796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715569855

Dyar, C., Taggart, T. C., Rodriguez-Seijas, C., Thompson, R. G., Elliott, J. C., Hasin, D. S., & Eaton, N. R. (2019). Physical health disparities across dimensions of sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and sex: Evidence for increased risk among bisexual adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1169-8

Eguchi, S. (2009). Negotiating hegemonic masculinity: The rhetorical strategy of “straight-acting” among gay men. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 38(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2009.508892

Elia, J. P. (2003). Queering relationships: Toward a paradigmatic shift. Journal of Homosexuality, 45(2–4), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v45n02_03

Elizur, Y., & Ziv, M. (2001). Family support and acceptance, gay male identity formation, and psychological adjustment: A path model. Family Process, 40(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100125.x

Engin, C. (2015). LGBT in Turkey: Policies and experiences. Social Sciences, 4(3), 838–858. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030838

European Commission. (2019). Report on Discrimination in the European Union. European Comission. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/surveyKy/2251

Everett, B. (2015). Sexual orientation identity change and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146514568349

Fasoli, F., Maass, A., Paladino, M. P., & Sulpizio, S. (2017). Gay- and lesbian-sounding auditory cues elicit stereotyping and discrimination. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(5), 1261–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0962-0

Fassinger, R. E., & Miller, B. A. (1997). Validation of an inclusive model of sexual minority identity formation on a sample of gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 32(2), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v32n02_04

Feinstein, B. A., Goldfried, M. R., & Davila, J. (2012). The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 917–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029425

Friedman, C. K., & Morgan, E. M. (2009). Comparing sexual-minority and heterosexual young women’s friends and parents as sources of support for sexual issues. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 920–936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9361-0

Goldbach, J. T., Tanner-Smith, E. E., Bagwell, M., & Dunlap, S. (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7

Gonçalves, J. A., Costa, P. A., & Leal, I. (2020). Minority stress in older Portuguese gay and bisexual men and its impact on sexual and relationship satisfaction. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(2), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00385-1

Gottschalk, L., & Newton, J. (2009). Rural homophobia: Not really gay. Gay & Lesbian Issues & Psychology Review, 5(3), 153–159.

Gough, B. (2007). Coming out in the heterosexist world of sport: A qualitative analysis of web postings by gay athletes. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 11(1–2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1300/J236v11n01_11

Habarth, J. M. (2015). Development of the heteronormative attitudes and beliefs scale. Psychology & Sexuality, 6(2), 166–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.876444

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(3), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005147708827

Herek, G. M. (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00051

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 1(2), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6

Herek, G. M. (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(1), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508316477

Herek, G. M., Chopp, R., & Strohl, D. (2007). Sexual stigma: Putting sexual minority health issues in context. In I. H. Meyer & M. Northridge (Eds.), The health of sexual minorities (pp. 171–208). Springer.

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2015). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Stigma and Health, 1(S), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/2376-6972.1.S.18

Hooghe, M., Claes, E., Harell, A., Quintelier, E., & Dejaeghere, Y. (2010). Anti-gay sentiment among adolescents in Belgium and Canada: A comparative investigation into the role of gender and religion. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(3), 384–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360903543071

Ikizer, E. G., Ramírez-Esparza, N., & Quinn, D. M. (2018). Culture and concealable stigmatized identities: Examining anticipated stigma in the United States and Turkey. Stigma and Health, 3(2), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000082

Jackson, S. (2006). Gender, sexuality and heterosexuality: The complexity (and limits) of heteronormativity. Feminist Theory, 7(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700106061462

Kitzinger, C. (2005). Heteronormativity in action: Reproducing the heterosexual nuclear family in after-hours medical calls. Social Problems, 52(4), 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.477

Legate, N., Ryan, R. M., & Weinstein, N. (2011). Is coming out always a “good thing”? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611411929

Lingiardi, V., Baiocco, R., & Nardelli, N. (2012). Measure of internalized sexual stigma for lesbians and gay men: A new scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(8), 1191–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.712850

Lopes, D., de Oliveira, J. M., Nogueira, C., & Grave, R. (2017). The social determinants of polymorphous prejudice against lesbian and gay individuals: The case of Portugal. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0230-4

López-Sáez, M. Á., García-Dauder, D., & Montero, I. (2020). Intersections around ambivalent sexism: Internalized homonegativity, resistance to heteronormativity and other correlates. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 608793. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608793

Lorenzi, G., Miscioscia, M., Ronconi, L., Pasquali, C. E., & Simonelli, A. (2015). Internalized stigma and psychological well-being in gay men and lesbians in Italy and Belgium. Social Sciences, 4(4), 1229–1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4041229

Maguen, S., Floyd, F. J., Bakeman, R., & Armistead, L. (2002). Developmental milestones and disclosure of sexual orientation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 23(2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(02)00105-3

Manning, J. (2015). Communicating sexual identities: A typology of coming out. Sexuality & Culture, 19(1), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-014-9251-4

Martin, A. D., & Hetrick, E. S. (1988). The stigmatization of the gay and lesbian adolescent. Journal of Homosexuality, 15(1–2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v15n01_12

Martos, A. J., Nezhad, S., & Meyer, I. H. (2015). Variations in sexual identity milestones among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-014-0167-4

McCarn, S. R., & Fassinger, R. E. (1996). Revisioning sexual minority identity formation: A new model of lesbian identity and its implications for counseling and research. The Counseling Psychologist, 24(3), 508–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000096243011

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286

Meyer, I. H. (2013). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(S), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.3

Mohr, J. J., & Fassinger, R. E. (2003). Self-acceptance and self-disclosure of sexual orientation in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: An attachment perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(4), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.4.482

Morris, J., & F., Waldo, C., F., & Rothblum, E. D. . (2001). A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61

Morrison, M. A., & Morrison, T. G. (2003). Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(2), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v43n02_02

Morrison, T. G., Parriag, A. V., & Morrison, M. A. (1999). The psychometric properties of the Homonegativity Scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 37(4), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v37n04_07

Nielsen, J. M., Walden, G., & Kunkel, C. A. (2000). Gendered heteronormativity: Empirical illustrations in everyday life. The Sociological Quarterly, 41(2), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2000.tb00096.x

Oliveira, J. M., Costa, C. G., & Nogueira, C. (2013). The workings of homonormativity: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer discourses on discrimination and public displays of affections in Portugal. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(10), 1475–1493. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.819221

O’Neil, M., & Çarkoğlu, A. (2020). The perception of gender and women in Turkey 2020. Kadir Has University. https://gender.khas.edu.tr/en/survey-public-perceptions-gender-roles-and-status-women-turkey

Pachankis, J. E., & Bränström, R. (2019). How many sexual minorities are hidden? Projecting the size of the global closet with implications for policy and public health. PLoS ONE, 14(6), e0218084. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218084

Pachankis, J. E., Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2015). The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 890–901. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000047

Pachankis, J. E., Mahon, C. P., Jackson, S. D., Fetzner, B. K., & Bränström, R. (2020). Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 831–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000271

Pacilli, M. G., Taurino, A., Jost, J. T., & van der Toorn, J. (2011). System justification, right-wing conservatism, and internalized homophobia: Gay and lesbian attitudes toward same-sex parenting in Italy. Sex Roles, 65(7), 580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9969-5

Pew Research Center. (2020). The global divide on homosexuality persists. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/

Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., Laghi, F., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Coming-out to family members and internalized sexual stigma in bisexual, lesbian and gay people. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3694–3701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0528-0

Ribeiro-Gonçalves, J. A., Pereira, H., Costa, P. A., Leal, I., & de Vries, B. (2021). Loneliness, social support, and adjustment to aging in older Portuguese gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00535-4

Riggle, E. D. B., Wickham, R. E., Rostosky, S. S., Rothblum, E. D., & Balsam, K. F. (2017). Impact of civil marriage recognition for long-term same-sex couples. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(2), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0243-z

Rodrigues, D. L., Fasoli, F., Huic, A., & Lopes, D. (2018). Which partners are more human? Monogamy matters more than sexual orientation for dehumanization in three European countries. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(4), 504–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0290-0

Rodrigues, D. L., Huic, A., & Lopes, D. (2019). Relationship commitment of Portuguese lesbian and gay individuals: Examining the role of cohabitation and perceived social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(9), 2738–2758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518798051

Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., Monteiro, L., & Prada, M. (2017). Perceived parent and friend support for romantic relationships in emerging adults. Personal Relationships, 24(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12163

Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., & Prada, M. (2019). Cohabitation and romantic relationship quality among Portuguese lesbian, gay, and heterosexual individuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 16(1), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-018-0343-z

Rosario, M., Hunter, J., Maguen, S., Gwadz, M., & Smith, R. (2001). The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(1), 133–160. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005205630978

Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E. W., Hunter, J., & Braun, L. (2006). Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. The Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552298

Ross, L. E., Salway, T., Tarasoff, L. A., MacKay, J. M., Hawkins, B. W., & Fehr, C. P. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755

Rostosky, S. S., & Riggle, E. D. (2017). Same-sex relationships and minority stress. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.011

Rothman, E. F., Sullivan, M., Keyes, S., & Boehmer, U. (2012). Parents’ supportive reactions to sexual orientation disclosure associated with better health: Results From a population-based survey of LGB adults in Massachusetts. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.648878

Ryan, W. S., Legate, N., & Weinstein, N. (2015). Coming out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual: The lasting impact of initial disclosure experiences. Self and Identity, 14(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1029516

Sattler, F. A., & Lemke, R. (2019). Testing the cross-cultural robustness of the Minority Stress Model in gay and bisexual men. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1400310

Seidman, S. (2005). From the polluted homosexual to the normal gay: Changing patterns of sexual regulation in America. In C. Ingraham (Ed.), Thinking Straight: The power, the Promise, and the Paradox of Heterosexuality (pp. 39–61). Routledge.

Seidman, S. (2009). Critique of compulsory heterosexuality. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 6(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2009.6.1.18

Šević, S., Ivanković, I., & Štulhofer, A. (2016). Emotional intimacy among coupled heterosexual and gay/bisexual Croatian men: Assessing the role of minority Stress. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1259–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0538-9

Shapiro, D. N., Rios, D., & Stewart, A. J. (2010). Conceptualizing lesbian sexual identity development: Narrative accounts of socializing structures and individual decisions and actions. Feminism & Psychology, 20(4), 491–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353509358441

Snapp, S. D., Watson, R. J., Russell, S. T., Diaz, R. M., & Ryan, C. (2015). Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations, 64(3), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12124

Swank, E., Fahs, B., & Frost, D. M. (2013). Region, social identities, and disclosure practices as predictors of heterosexist discrimination against sexual minorities in the United States. Sociological Inquiry, 83(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12004

Taggart, T. C., Rodriguez-Seijas, C., Dyar, C., Elliott, J. C., Thompson, R. G., Hasin, D. S., & Eaton, N. R. (2019). Sexual orientation and sex-related substance use: The unexplored role of bisexuality. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 115, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.12.012

Tatum, A. K., & Ross, M. W. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of sexual minorities’ acceptance concerns and internalized homonegativity on perceived psychological stress. Psychology & Sexuality, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1775688

Thies, K. E., Starks, T. J., Denmark, F. L., & Rosenthal, L. (2016). Internalized homonegativity and relationship quality in same-sex romantic couples: A test of mental health mechanisms and gender as a moderator. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000183

Toomey, R. B., McGuire, J. K., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence, 35(1), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001

Tran, H., Ross, M. W., Diamond, P. M., Berg, R. C., Weatherburn, P., & Schmidt, A. J. (2018). Structural validation and multiple group assessment of the Short Internalized Homonegativity Scale in homosexual and bisexual men in 38 European countries: Results from the European MSM Internet Survey. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1380158

Wagner, G. J., Aunon, F. M., Kaplan, R. L., Karam, R., Khouri, D., Tohme, J., & Mokhbat, J. (2013). Sexual stigma, psychological well-being and social engagement among men who have sex with men in Beirut, Lebanon. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(5), 570–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.775345

Walch, S. E., Ngamake, S. T., Bovornusvakool, W., & Walker, S. V. (2016). Discrimination, internalized homophobia, and concealment in sexual minority physical and mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000146

Whitton, S. W., Dyar, C., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2018). Romantic involvement: A protective factor for psychological health in racially-diverse young sexual minorities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000332

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the collaboration of the following organizations, social venues, and websites from Portugal and Turkey for their assistance during the process of data collection: AMPLOS, AMPLOS Porto, Ayı Sözlük, CaDiv-Caminhar na Diversidade, Caleidoscópio LGBT, Casa Qui, Centro LGBT, Checkpoint LX, EsQrever, Genç LGBTİ Derneği İzmir, ILGA Portugal, Istanbul Bears, LGBTI News Turkey, LGBTI Viseu, LISTAG, Motociclistas Alternativos Portugueses, Opus Gay Madeira, Pois.pt, Portogay, Portugalgay.pt, Queer IST, Rumos Novos, Rede ex Aequo, Türkiye LGBTİ Birliği, and Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi ODA. Finally, we wish to express our gratitude with every one of the participants that collaborated in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors work in study conception and design. CAT collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data under the supervision of DLR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CAT and was revised by DLR. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Torres, C.A., Rodrigues, D.L. Heteronormative Beliefs and Internalized Homonegativity in the Coming Out Process of Portuguese and Turkish Sexual Minority Men. Sex Res Soc Policy 19, 663–677 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00582-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00582-x