Abstract

Introduction

With Trump’s presidency came a rise in the oppression of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people, as the nation witnessed a removal of protections for TGD people.

Methods

We examined the daily experiences of 181 TGD individuals (ages 16–40, M age = 25.6) through their reflections about daily stressors over the course of 8 weeks (data collected fall 2015–summer 2017), some of which reflected shifts during the election period.

Results

During the 2016 presidential election, participants reported a rise in marginalization stress and the subsequent impact on safety, mental health, and well-being. There were three emergent themes: External Rejection and Stigma from Dominant Culture; Supporting the TGD Community; and Fear for the Self and Development of Proximal Stressors.

Conclusions

In line with marginalization stress theory, participants vocalized the progression from exterior stigmatization to proximal stressors and their heightened sense of vigilance and fear of the dominant culture.

Policy Implications

Based on the results of this study, policy makers and TGD advocates must work to ensure that political rhetoric and action do not serve to further marginalize and erase TGD communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On July 26, 2017, President Donald Trump tweeted “After consultation with my Generals and military experts, please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military.” Throughout his time in office, Trump has actively sought to roll back Obama administration protections for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people. This has included actions such as banning TGD people from military service, working to limit bathroom and public restroom access, and spouting volatile and stigmatizing rhetoric. TGD people have been systematically erased and rendered invisible through the exclusion and stigmatization from social, political, personal, and medical spheres of the United States (Bauer et al., 2009). Trump’s vocal affirmation of this prejudice and marginalization, along with similar racist and heterosexist rhetoric (Carter, 2018; Perry, 2018), directly impacts the lives of individuals who fall outside of the White, cisgender male, heterosexual hegemony. In other words, Trump’s rhetoric disregards civility and respect for others and opens the door for further discrimination and violence against these groups.

The minority stress model, which has been termed marginalization stress by others, elaborates upon the health issues related to stigma and marginalization from hegemonic culture (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). This model outlines the cycle of support and rejection through experiences of both direct discrimination and internalized expectations of rejection that arise as a product of social oppression. Although Meyer’s model specifically referred to lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people, marginalization stress can be extended to include the discrimination faced by TGD people (Breslow et al., 2015; Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Testa, Habarth, Peta, Balsam, & Bockting, 2015). Breslow et al. (2015) assert that, although the identities themselves are different, the types of discrimination and stigmatization likewise directly contribute to internalized stigma and an increase in mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. The caustic discourse about TGD people in the political sphere has created an echo chamber of cissexist sentimentality and discrimination. As the political and social voices of cissexism reverberate off of each other, they become stronger and more aggressive, perpetuating and reinforcing the systemic cissexism present throughout American culture. This echo chamber of external cissexism leads to expected stigmatization, internalization of stigma, and a cycle of continued marginalization stress with heightened risks of negative health outcomes.

Although some research has been done on the negative health impacts of the 2016 election on LGBTQ people (Gonzalez, Ramirez, & Galupo, 2018), to the authors’ knowledge little to no research has been done on the effects of Trump’s election and anti-trans rhetoric on TGD people. This study takes a qualitative approach, examining the daily stressors and ruminations of TGD people during the 2016 presidential election. Based on this data, there are clear trends of anxiety and distress due to political events and rhetoric, specifically in relation to the cissexist actions of Trump and his (then upcoming) administration. Through the lens of marginalization stress, this study seeks to explore TGD stigmatization in relation to national political discourse.

Stigma, Marginalization Stress, and Gender Identity

Stigma is a systematic process of negative stereotyping and discrimination leading to social and cultural rejection. This rejection and social isolation can result in an internalization of these negative stereotypes and concealment of identity for those labeled as a stigmatized group. Link and Phelan (2006) define stigma as a variety of overlapping elements creating a label of otherness and rejection of the stigmatized identity from dominant culture. Stigma becomes normalized and rationalized on a national level, infiltrating not only social interactions, but structures of power and hegemonic control. This structural stigma restricts the resources and opportunities available to these stigmatized groups, placing them at a disadvantage within socioeconomic, medical, social, and political environs and increasing their risk of negative health outcomes (Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013; Hope et al., 2016; Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015; Link, 2017; Link & Phelan, 2006).

The stigma and oppression of TGD people can result in concealment of either their transgender identity or transition history (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Holt et al., 2019a) and fear of discrimination (Holt, Hope, Mocarski, & Woodruff, 2019b; Meyer, 2003; Testa et al., 2015). Marginalization stress details how stigmatization places extreme stress upon minority groups and subsequently how this stress leads to higher rates of mental health problems as well as internalized stigma. These stressors often come in the form of social and political stigma and discrimination, resulting in rejection and isolation from the dominant culture. As a product of this social rejection, TGD people may experience a negative self-image, identity concealment, and expectations of future rejection, which can adversely impact mental health (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003, 2013; Testa et al., 2015).

According to marginalization stress, TGD individuals develop a sense of extreme vigilance in order to deal with expectations of discrimination and othering (Gonzalez et al., 2018; Holt et al., 2019c; Meyer, 2003). Eventually, these stigmatizing messages may be internalized by individuals as the dominant culture continues to assert hegemonic definitions of normalcy and deliver extreme consequences, such as physical violence, for those who fall outside of cisgender identities (Mocarski et al., 2019; Testa et al., 2015). As such, individuals can come to expect rejection from others or develop internalized stigma as a result of social marginalization (Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Rood et al., 2016, 2017). Marginalization stress thereby allows for an understanding of how minority stressors impact the mental health and resiliency of TGD people when they are forced to navigate the constructed world of hegemonic control and stigma.

Community connection and engagement aids in building individual resiliency. Meyer (2013) asserts that interactions with others are “crucial for the development of a sense of self and well-being” (p. 4). These interactions and connections with others are especially important as TGD people and other minority groups begin to anticipate and develop an expectation of rejection from members of the dominant culture (Gamarel, Reisner, Laurenceau, Nemoto, & Operario, 2014; Testa et al., 2015). One way that TGD people may cope with this targeting is to develop a sense of cohesiveness and connection within TGD communities. It also is important to note that concealing an identity may serve a protective function rather than being based out of shame or other explanations (Rood et al., 2016). Social and political environment, as well as geographical, religious, and socioeconomic factors, may also influence stigma and how this is experienced (Goffman, 1963; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Hughto et al., 2015; Link, 2017; Link & Phelan, 2006; Meyer, 2013; Smart & Wegner, 2000).

As the current presidential administration continues to spout its cissexist political rhetoric into the public sphere, hegemonic definitions of the gender binary are reasserted upon TGD individuals through political, social, and medical regulations and stigma (Brown, 2009; Gonzalez et al., 2018; Gressgård, 2010; Stryker, Currah, & Moore, 2008). The negative effects that these forms of policy-based stigmatization and outright discrimination have on sexual and gender minorities are proven to have long-lasting effects, even once these prejudiced policies have been rescinded or overturned (Gonzalez et al., 2018; Russell, Bohan, McCarroll, & Smith, 2011). The 2016 elections were observed by sexual and gender minorities with a general increase in the expectation of discrimination, and a general fear met with the disruption of support networks due to the undercurrents of political vitriol (Gonzalez et al., 2018; Veldhuis, Drabble, Riggle, Wootton, & Hughes, 2018).

In this article, we ask the questions: (1) how does national political discourse impact gender minorities and expectations of stigma and discrimination? and, more specifically, (2) how did the 2016 presidential election impact TGD people? Through a qualitative analysis utilizing marginalization stress theory, this article includes an analysis of daily ruminations and diary entries regarding stressors encountered by TGD individuals in order to understand the ways in which political discourse directly impacts the well-being of TGD people.

Methods

The study consisted of two parts of data collection, with participants being eligible to participate in only one of the following: (1) a daily diary study on marginalization stress, mental health, substance use, and HIV risk behaviors; and (2) a one-time survey about marginalization stress, mental health, and related variables. In order to be eligible for the daily diary study portion, participants had to be between the age of 16–40 years old; live in the United States; identify as trans men, trans women, genderqueer, or non-binary; had sex in the past 30 days, and either binge drank or used substances in the past 30 days. Those that did not meet the full criteria but who were at least 16 years old, TGD identifying, and living in the United States were asked to participate in the one-time survey. The findings reported in this article are specifically from the daily diary data. These inclusion criteria were used because the daily diary study was intended to examine the associations between minority stress, mental health, substance use, and HIV risk behaviors. Some of these behaviors may be infrequent, such as sexual activities, so these criteria were used to help ensure that such events would be reflected across the 2 months of the study.

Participants were recruited through a variety of means, including online social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and others; via electronic study flyers shared with various community organizations that work with TGD individuals; and via in-person at community events. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the investigators’ institutions with a waiver of parental permission under 45 CFR 46.408(c). All participants provided their consent/assent to participate in the study, which was completed via an online survey. Because this was an online study, we took several steps to ensure the quality of the data, such as conducting a screening procedure and screening for duplicates (a full description of these procedures is described elsewhere; Puckett, Maroney, Wadsworth, Mustanski, & Newcomb, 2020). We also incorporated a community advisory board who helped to provide feedback about the study aims, questions, and preliminary data interpretations.

After cleaning the data (e.g., removing duplicate responses, removing participants with minimal data), there were 181 participants enrolled in the daily diary study. After completing a baseline questionnaire, participants received daily surveys for 8 weeks, followed by a final, follow-up survey. The data for the current analysis was derived specifically from the daily surveys that the participants completed repeatedly for the 56 days. There were 177 participants who completed any of the daily surveys and we removed participants with less than a week’s worth of data, resulting in a final sample of 167 individuals with daily survey data. Across the 167 participants with daily survey data, there were 7436 daily surveys completed out of the 9352 possible daily observations (completion rate of 79.5%). Of these 167 participants, 166 (99.4%) provided written responses at some points in response to the items on rumination topics, with 2431 written responses overall. The number of responses across the 8 weeks ranged from 1 to 53, with an average of 15 responses per participant. And, across all participants and all days, there were a total of 446 written responses about stressful events that occurred during the daily surveys, which were provided by 116 (69.5%) of the 167 participants retained in the daily survey portion. Of the participants who provided responses about stressful events, these ranged from 1 to 22 responses over the 56 days (M = 4).

Participants in the full sample across the duration of the study (N = 181) included 88 trans men, 34 trans women, 17 genderqueer individuals, and 42 non-binary individuals from ages 16 to 40 (M age = 25.6 years; SD = 5.6). Approximately 41% of the sample had an income below $10,000 per year. The majority of the sample, 85.1%, were White. See Table 1 for the full sample demographics.

Rumination Responses

Participants were asked, “Yesterday, did you have a hard time getting things off your mind? This includes things that are completely unrelated to your gender identity.” with response options of “yes” and “no.” If participants indicated “yes,” they were given the following prompt: “Briefly, tell us what you weren’t able to stop thinking about.” Participants then rated how strongly this was related to their gender identity on a 5-point scale from 1 (very strongly related) to 5 (not related at all) to assist with the interpretation of responses.

Daily Stressors

Participants were provided with a checklist of stressors that they could have encountered. Participants were also allowed to indicate that something else stressful happened to them related to being TGD (“Were there any other experiences where you felt like you were treated differently or where you felt like you encountered stigma related to being trans or gender nonconforming?”). If participants responded “yes,” they were provided a textbox to elaborate on this experience.

Analytic Procedures

For the written responses, we conducted a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The thematic analysis included the following steps: (1) familiarization with the data by reviewing all written responses; (2) generating initial codes via the development of a codebook with definitions of each code; (3) searching for themes by comparing codes to one another and examining relationships between themes; (4) reviewing potential themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing a written description of these findings. More specifically, the second author developed an initial codebook by reviewing all data, in which descriptive codes and definitions were developed. The first author conducted another review of the rumination data, applying these codes and making modifications as needed to the codebook to clarify wording or the boundaries of codes. The first and second author reviewed their coding of 10% of the rumination data to ensure that coding was consistent across coders and that the definitions were clear. This review was conducted during a meeting in which these two authors discussed discrepancies in coding and the rationale behind such coding to reach consensus on the proper application of codes to the data and agreement on the coding procedures moving forward. Following this, the first author coded all rumination data. The second author then reviewed all codes to ensure consistency within each code. All qualitative analyses were conducted in NVivo. Although a variety of codes and themes emerged in the data, we focus here on a specific analysis of data related to political discourse, pulling data from the questions about rumination and daily stressors.

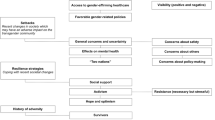

Analysis: Political Discourse and the Self

Throughout the data, the theme of political fear and unrest was distinctly prevalent in the process and aftermath of the 2016 elections. The rumination responses focused on the rising popularity of Trump and his supporters throughout the campaign process, the horror and disgust felt when he won the election, and the subsequent fear surrounding his early days in office as he began to roll back protections for TGD people (Gonzalez et al., 2018). The comments and ruminations of TGD participants in regard to the political landscape during the study centered on three emergent themes: (1) External Rejection and Stigma from Dominant Culture, (2) Seeking to Support the TGD Community, and, finally, (3) Fear for the Self and the Development of Proximal Stressors. These three themes fall in line with marginalization stress theory, as the participants vocalized the progression from exterior stigmatization, seeking connection with the TGD community, and finally individual internalization of stigma and a heightened sense of vigilance and fear of the dominant culture. Through this data, the tangible effects of discriminatory political rhetoric on the mental health and well-being of TGD people are mapped out as participants vocalized their fear and gradual increases in experiences of prejudice and stigma. The Trump administration’s political rhetoric was tied to perceived, expected, and enacted stigma, and the subsequent, often unavoidable internalization of stigma and rise in expectations of rejection for TGD people throughout the United States.

External Rejection and Stigma from Dominant Culture

One of the most prevalent themes was persistent feelings of rejection and abandonment from the dominant culture through Trump’s election. Participants regularly commented on having been betrayed by close friends and family who voted for Trump, demonstrating an understanding that Trump’s election served to further cast them out of hegemonic culture. The sense of rejection was articulated through feelings of mistrust, abandonment, and outright anger against a society that decided, through their voting, that TGD people did not matter. One participant outlined their preoccupation with the results of the election explaining:

My fear of post-election will be on my mind for a long time. So many of my old friends are republicans and are saying ‘I voted for Trump but I’m not racist, anti LGBT, etc.’ but they are and I can’t stop thinking about that and how I can possibly say something. I’m so full of fear and anger and I’m helpless.

This feeling of helplessness was vocalized by many of the participants as they suddenly felt their voice within the political sphere vanish, as half of the country voted to support a man who acted so clearly against equal rights and respect for TGD people. This denial or ignorance from the hegemonic culture left many participants feeling as though the little political power they had gained within the prior administration was suddenly pulled out from under them, casting them back further into a cycle of fear and discrimination. As another participant stated, “How do so many people in this country hate me?”

Hopelessness and a sense of losing control pervaded many of the ruminations. Participants commented on the increase in anti-TGD rhetoric and action during and after the election. As a participant explained, “Someone on the radio said, ‘liberals are making up new genders now.’ I don’t know how to avoid hearing someone take a shit on nonbinary people.” Later in their ruminations they also stated, “Some pile of shit on radio blamed transgender kids for being suicidal.” This public anti-TGD rhetoric and sentiment increased stigmatization and the threat of violence in the public sphere. Many participants, this person included, mentioned fear for personal safety as a result of how the elections turned out and a sudden rise in hate speech. Another participant explained:

I am dealing with a lot of online hate and people defending that online hate. There is a whole lot of violence going on in the US right now because of the results of the election and it is scaring me and affecting me. Yesterday I spent over an hour trying to convince a person who I thought was my friend that discrimination and hate is bad... I never thought that was in question.

Some that were considered friends and allies became suspect for their ignorance and support of the Republican Party. This suspicion turned to mistrust, fear, and in many cases anger as participants reacted to those in power that allowed this to happen. One participant exclaimed, “HOW COULD THIS HAPPEN?! I hate all of my Libertarian friends… I need to be drunk.” This feeling of despair, anger, and helplessness against a dominant culture that allowed a man like Trump to be president led to a reactivity towards those who had previously been perceived as friends. Furthermore, this participant’s rumination points to a larger trend of turning to coping mechanisms such as drinking in order to deal with the stress of Trump’s election. Many participants articulated losing support systems of family and friends, as those they had previously trusted “allowed” Trump to be elected. This loss of support networks and increase in felt discrimination further isolated participants.

Trump’s election and political presence led to the deterioration of many family and support networks for participants. For example, one participant lost faith in their religious community: “I learned that Hasidic Jews support Trump. As someone who is Jewish (though not Hasidic) it completely blows my mind and I can’t understand it.” They went on to elaborate how the election process and voting measures made it difficult for Hasidic and non-Hasidic Jewish people to oppose Trump as many of the DNC caucuses happened on a Saturday, meaning that “Jews here who are registered Democrats will not be able to go without violating Shabbat.” This participant experienced a sense of rejection and abandonment from the Jewish community as sects of their religion advocated for a man that spoke against this participant’s gender identity. Furthermore, this participant detailed the sensation of rejection by the DNC because they only held their caucuses in the area on Saturdays, making it difficult for the Jewish community to attend. This rumination demonstrates how hegemonic political actions on both sides of the aisle are ignorant of those outside of the dominant culture. This participant experienced feelings of rejection and stigmatization by both their religious community and by their political party. This abandonment factors into the increased experiences of betrayal and discrimination by hegemonic culture, as even the “safe spaces” allow for the continuation of political vitriol targeting TGD people. This rejection increased the expectation and experience of outright discrimination from the dominant culture.

Throughout these entries, experiences of rejection and abandonment by dominant social culture pervade the perceptions of the 2016 presidential election. This rejection and abandonment quickly turned to outright discrimination and anti-TGD rhetoric coming from within the support systems of TGD people. Some support networks fell apart as TGD people were isolated from the dominant culture through stigma and discrimination. As one participant explains,

I spent a good hour yesterday arguing with my father about the fact that lgbtq rights were important and how the hate crimes in this country have skyrocketed because of Trump’s win in the election. He kept pushing his opinions and ignoring mine and minimizing the suffering of minorities in this counter, including lgbtq people… He knows I’m not straight and he still believes these things… My mother isn’t straight and she voted for him too… I didn’t argue with my mother about it, but she told me that she thought it was the right thing to do to vote for Trump even though he is a threat to us and everything we hold dear.

This denial and ignorance by some family members and support networks led to a sense of hopelessness and helplessness as participants were exposed to the political vitriol that denied their right to exist, with this creeping throughout their support networks.

The majority of participants commented on an increase in anxiety and outright fear for their lives as a result of the 2016 elections, as racist, heterosexist, and cissexist sentiment was brought out into the open and given a strong platform in the Presidential office, as one participant noted, that Trump supporters were “being openly hostile, both [in] person and on social media.” This increase in fear and anxiety led to vigilance as expectations of discrimination increased. This heightened vigilance placed an increased strain on many TGD people as they were in a constant state of fear and mistrust of those around them in an attempt to protect themselves from anti-TGD rhetoric and violence. As cissexist voices in the dominant culture increased, they reverberated upon themselves and became stronger—allowing and encouraging acts of discrimination and violence against TGD people while also leading to an increase in the risk of psychological distress for TGD people.

Seeking to Support the TGD Community

Past research has demonstrated that feelings of community belongingness and connection serve to mitigate the negative effects of minority stress and expectations of discrimination (Frost & Meyer, 2009; Gonzalez et al., 2018). Many participants articulated a distinct fear of the changes in TGD rights under the Trump administration and fear for the broader LGBTQ community. However, this fear for the LGBTQ community served to further reinforce feelings of isolation from both the dominant culture and the TGD community. Fear was largely demonstrated through either fear of specific policy changes or as a general fear for TGD and other marginalized groups. For example, one participant commented on their preoccupation with Trump winning the election, explaining that they were “Very concerned for my rights and safety and the rights and safety of all people of minority groups.” Another participant mirrored this preoccupation: “Wondering how trans rights are going to be rolled back in this country. I’m from [Conservative Southern State], so wondering if it will ever be safe to move home.” Safety for individual members of the TGD community was a major theme throughout the ruminations as participants worried not only about themselves, but about their friends and the repercussions of Trump’s policy changes on the lives of TGD people. As one participant stated:

The election results have me in a panic and I'm scared. Yesterday was quiet on campus in a weird way. Still, many of my friends expressed that strangers singled them out for being trans or queer and POC [person of color]. At my office we put out information urging trans people to get their marker changed for passports and social security ASAP. I'm scared for myself and everyone I care about.

From the beginning of Trump’s presidential term, he began scaling back Obama era protections for LGBTQ people. Specifically, many of the TGD participants mentioned the rolling back of bathroom rights, Trump’s transgender military ban, and regulations inhibiting access to gender affirming healthcare. These policy changes targeting the TGD community increased the sense of powerlessness and oppression facing TGD people. On a state level, participants voiced concerns about needing to move for their safety and protection, leaving states that are less supportive of TGD rights. These comments were generally voiced in relation to a general fear for the protections and rights of the TGD community, as they watched many of their protections be stripped away. “Privilege and oppression, grief and change,” as one participant commented, were at the forefront of these discussions.

Despite articulation of fears for the general community, a sense of isolation and loneliness pervaded these ruminations. Paired with the loss of family and friends in their support networks, many participants similarly reported feelings of isolation from the larger TGD and LGBTQ communities. This isolation from LGBTQ and TGD communities can lead to heightened risk of internalization of cissexist messages and decreases in self-worth (Gonzalez et al., 2018; Holt, Hope, Mocarski, Meyer, et al., 2019a). Rather than demonstrating community cohesion and belongingness, the majority of these ruminations came from a mindset of hopelessness, as the dominant culture stripped away their power and protections, leaving them little recourse to fight back against the injustices piled against them. As one participant said:

I am scared for myself but also for my queer, homeless clients. Right now, government issues are the scariest part considering they will dictate my own, my clients, and other folks access to medical and mental health care[...] I am stressed about work--staff are dropping like flies around here. I am the only queer Case Manager in [Name] County, so I feel obligated to stay even when the environment is unhealthy […] They do not support me, nor do they care about my clients.

This participant in particular was faced with a growing sense of isolation and abandonment from the dominant culture, which manifested at work, and they were shouldering the burden of hopelessness for the queer community in their county. This latter action is noble, as they had become a defacto community leader due to the erosion of support from the dominant culture.

Many participants expressed anger and frustration, but the majority focused more specifically on feelings of despair. Even in instances of protest and attempts to fight back, one participant vocalized, “How hopeless I feel that the anti-Trump protest I went to had more alt-right screaming men than protesters.” This is both a feeling of hopelessness and betrayal by the dominant culture and a feeling of isolation and abandonment as too few people showed up to make the protest strong enough to stand against the counterprotest. These ruminations of community helplessness and isolation served to further internalize marginalization stress and stigma throughout the TGD community, as TGD people were faced with seemingly insurmountable levels of stigma and discrimination from the Trump administration.

Fear for the Self and Development of Proximal Stressors

Feelings of community isolation heightened the echo chamber of cissexist messaging, allowing the infiltration of anti-trans discrimination and stigma from the dominant culture onto TGD people. This can lead to an increase in fear, worthlessness, and guilt in the face of the pervasive negative TGD image forced upon participants by hegemonic systems of power and oppression. These entries reflected vigilance and terror as participants felt threatened by violent physical attacks, instilling a lack of agency. For example, as one participant explained, “I was worried about the future. What if trump gets elected and this country starts heading down a path of purging everyone not deemed normal. I’ll definitely be taken and killed for being trans.” Many participants questioned their safety in the United States and spoke of preparing themselves to face violence and discrimination, as one participant explained, “Neo Nazi’s flooded into my town last night and a giant protest was held against it. The protest turned very violent and I felt like being a small male, as a result of being trans, left me as a target.” Fear and lack of safety play directly into marginalization stress theory as these led to an increase in vigilance, mistrust, and overall anxiety. As TGD people heard the aggressive and violent cissexist rhetoric from right-wing politicians, fear for personal safety was at the forefront of their minds, increasing anxiety and fear of being “outed” as TGD to the general public. As a participant commented, “I’m concerned now with the results of the election if I’ll even be able to come out safely, let alone transition smoothly.” This fear led to discussions of moving and hiding throughout the ruminations as some participants questioned whether moving to a new state would help protect them from some of the more extreme anti-TGD national sentiment. A number of participants spoke of developing their plan of action, where they would go, and what steps they needed to take to ensure their safety through hiding records of their gender identity or gender history.

The ability to affirm one’s gender under the Trump administration was another major theme throughout the discourse about political events. For example, a participant stated, “How am I going to afford transitioning during the trump regime? Talk about regretting not doing it earlier. Of course, I didn’t figure out I was nonbinary until last year.” Another participant mirrored this concern: “I am also still trying to get my next month’s supply of testosterone. And beginning to worry that I may not be able to access testosterone for a long time due to the political climate of the country...” This theme of fear based on access to gender affirming healthcare points to the physical as well as mental effects of marginalization stress. As the Trump regime took over the public sphere, cissexist sentiment crept into all aspects of American life, including the healthcare system. With the scale back of TGD protections, as well as the military ban, President Trump’s hateful rhetoric and policies have made it harder for TGD people to find gender-affirming care.

Furthermore, many participants reported fear about being able to affirm their gender at all without discrimination and being outed as TGD. This fear of discrimination caused many of the participants to conceal their gender identity and avoid interacting with the medical community in order to protect themselves from discrimination and violence. Trump’s anti-TGD policies also forced many TGD people to “out” themselves through bathroom policies and gender markers. During the voting process, some participants sought ways to conceal their gender identity in order to avoid cissexist repercussions. As one participant explained, “Voting was a weird experience due to my i.d. not matching my name, but I dressed masculinely to avoid any bother.” Another participant shared their fears of having to revert back to marking their gender assigned at birth on official documents, stating “I couldn’t stop thinking about having to check the sex assigned at birth instead of what I identify as on work documents.” In the workplace, this could lead directly to discrimination. This means that political policies dictating gender identifiers on government and work-based documents serve to identify TGD people, placing them in a situation where they are at higher risk of discrimination and stigmatization by cissexist sentiment.

Trump’s vitriolic anti-TGD rhetoric has real-world implications, as TGD people are bombarded with discriminatory attacks and hate speech, making it difficult for them to get the resources they need to affirm their gender. In order to counteract this public “outing,” a number of participants discussed plans to ensure that their documents were all in order and changed to their affirmed gender identity to avoid having to use their gender assigned at birth on official documents. Depending on the state in which they resided and were born, this may not have been possible as the process to changing gender markers on birth certificates, drivers licenses, and other forms of identification is often lengthy and difficult, and in some cases not allowed.

The deleterious nature of this cissexist rhetoric was echoed throughout the entries, as participants voiced fear for personal safety and finally with some participants noting feelings of guilt alongside their own powerlessness in this scenario. Some participants commented on feelings of guilt for Trump’s rise to power either for having voted for Johnson or simply by feeling as though they had not done enough to speak out against Trump. This seemed to emphasize that participants were searching for some sense of agency and meaning making amidst a period when they felt severely disempowered. As one participant commented, “I voted for Johnson, I thought Hillary would win...I feel so much guilt.” This sentiment was paired with trends of negative self-image and uncertainty as to how to continue to reside in a nation that allowed for the election of Trump. Many participants voiced internal fears of not having done enough to fight against him as they assumed that there was no way that he could win.

What these testimonies point to is a demonstrated internalization of powerlessness and attempts to make meaning in the face of the cissexist rhetoric bombarding TGD people from the dominant culture, as one participant noted:

Well the president elect is a bigot, the Senate is republican and supreme court is at risk. Fuck, as a nonbinary person I don’t have legal recognition to begin with. Suffice to say, today is a bad day for all of us.

Increased expectations of rejection was paired with a decreased sense of power and agency over the individual body as gender affirmation was made more and more difficult. TGD people were therefore living in a constant state of vigilance with fear of retaliation and some were forced to hide their gender identity from the dominant culture in order to avoid violence and discrimination. These entries demonstrated the direct impact that political rhetoric and policy has on minority stress for TGD people throughout the United States.

Conclusion

Trump’s election and subsequent presidency have increased the negative impacts of minority stress on TGD people through the vitriolic rhetoric surrounding TGD identities and rights. These daily entries demonstrated the pattern of hegemonic stigmatization and discrimination through the public displays of prejudice and rolling back of TGD protections and rights. These political and rhetorical actions had a direct impact on the lives of TGD people as the Trump administration sought to eradicate their right to exist and continues to do so. This cissexist discourse in the public sphere created a cycle of anti-TGD sentimentality and discrimination, increasing stigmatization against TGD people, isolating them, and divesting them of their agency and power in the hegemonic sphere.

The daily experiences of TGD people throughout the election and the early days of the Trump presidency demonstrate the process of marginalization stress through external stigma and betrayal by the dominant culture, feelings of isolation from and fear for the larger TGD community, and the subsequent proximal effects of this fear and stigma. The political cissexist rhetoric forces TGD people into a state of vigilance, separating them from their support networks both in the dominant culture and within the TGD community. This isolation and the perpetual sense of helplessness, fear, and anger increase both the mental and physical deleterious effects of minority stress as TGD individuals seek to cope with the increase in hate speech and policy changes. Although the data clearly demonstrates this cycle, we must also consider methodological effects. Daily diaries are meant to center the writer as the topic and rumination is meant to ask about what someone is stressed about, therefore positive community building and connections may be excluded from the data due to these issues.

Although novel, this study is not without limitations. For one, the inclusion criteria of the study may have influenced the results. More specifically, by including participants who reported binge drinking or substance use in the month prior to their enrollment in the study, these participants may have been experiencing higher levels of stress or different methods of managing stressors that would be seen in a broader sample of TGD people. The limited racial diversity of our sample is another significant limitation. Our sample was 85% White and we know from other research that TGD people who are Black and other people of color are disproportionately targeted with violence and marginalization compared to White TGD people (Gossett, Stanley, & Burton, 2017). As such, future research is needed to verify that the processes found in this study would look similar in a more diverse sample.

Marginalization stress creates a lens through which these ruminations can be analyzed and serves to demonstrate the direct lines of power and oppression that stigmatize TGD people, starting from the presidency and trickling down through all aspects of life. These findings may be self-evident for those within the TGD community; however, what this study demonstrates is how political action and rhetoric directly impact the lives of marginalized people. With such a volatile man in the presidency, aggressive and hateful speech has become more common throughout American culture, as Trump’s rhetoric gives rise and force to those who seek to oppress others different from themselves. This is clear when looking at TGD people and how the Trump administration has treated those who identify outside of the cisnormative US society. This rhetoric and stigmatization of TGD people have substantial lasting effects on both the mental and the physical health of TGD people through the increased threat of physical violence and the proximal effects of marginalization stress.

References

Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., & Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20(5), 348–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004.

Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Breslow, A. S., Brewster, M. E., Velez, B. L., Wong, S., Geiger, E., & Soderstrom, B. (2015). Resilience and collective action: Exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000117.

Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Brown, W. (2009). Regulating aversion: Tolerance in the age of identity and empire. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400827473.

Carter, C. (2018). The paradox of dissent: Bullshit and the Twitter Presidency. In President Donald Trump and His Political Discourse: Ramifications of Rhetoric Via Twitter, edited by Michele Lockhart (pp. 93–113). Routledge.

Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2009). Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of counseling psychology, 56(1), 97–107.

Gamarel, K. E., Reisner, S. L., Laurenceau, J.-P., Nemoto, T., & Operario, D. (2014). Gender minority stress, mental health, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgender women and their cisgender male partners. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037171.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Shuster.

Gonzalez, K. A., Ramirez, J. L., & Galupo, M. P. (2018). Increase in GLBTQ minority stress following the 2016 US presidential election. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14(1–2), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2017.1420849.

Gossett, R., Stanley, E. A., & Burton, J. (2017). Trap door: Trans cultural production and the politics of visibility. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gressgård, R. (2010). When trans translates into tolerance-or was it monstrous? Transsexual and transgender identity in liberal humanist discourse. Sexualities, 13(5), 539–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460710375569.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069.

Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597.

Holt, N. R., Hope, D. A., Mocarski, R., Meyer, H., King, R., & Woodruff, N. (2019a). The provider perspective on behavioral health care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals in the Central Great Plains: A qualitative study of approaches and needs. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000406.

Holt, N. R., Hope, D. A., Mocarski, R., & Woodruff, N. (2019b). First impressions online: The inclusion of transgender and gender nonconforming identities and services in mental healthcare providers’ online materials in the USA. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1428842.

Holt, N. R., Huit, T. Z., Shulman, G. P., Meza, J. L., Smyth, J. D., Woodruff, N., Mocarski, R., Puckett, J. A., & Hope, D. A. (2019c). Trans collaborations clinical check-in (TC3): Initial validation of a clinical measure for transgender and gender diverse adults receiving psychological services. Behavior Therapy, 50, 1136–1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.04.001.

Hope, D. A., Mocarski, R., Bautista, C. L., & Holt, N. R. (2016). Culturally competent evidence-based behavioral health services for the transgender community: Progress and challenges. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(4), 361–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000197.

Hughto, J. M. W., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010.

Link, B. G. (2017). Commentary on: Sexual and gender minority health disparities as a social issue: How stigma and intergroup relations can explain and reduce health disparities. Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12236.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2006). Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet, 367(9509), 528–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-673(06)68184-1.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674. http://dx.doi.org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.3–626.

Meyer, I. (2013). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.3.

Mocarski, R., King, R., Butler, S., Holt, N. R., Huit, T. Z., Hope, D. A., Meyer, H. M., & Woodruff, N. (2019). The rise of transgender and gender diverse representation in the media: Impacts on the population. Communication, culture & critique, 12(3), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz031.

Perry, S. (2018). President Trump and Charlottesville: Uncivil mourning and White supremacy. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 8.

Puckett, J. A., Maroney, M. R., Wadsworth, L. P., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2020). Coping with discrimination: The insidious effects of gender minority stigma on depression and anxiety in transgender individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76, 176–194.

Rood, B. A., Reisner, S. L., Surace, F. I., Puckett, J. A., Maroney, M. R., & Pantalone, D. W. (2016). Expecting rejection: Understanding the minority stress experiences of transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgender Health, 1, 151–164.

Rood, B. A., Reisner, S. L., Puckett, J. A., Surace, F. I., Berman, A. K., & Pantalone, D. W. (2017). Internalized transphobia: Exploring perceptions of social messages in transgender and gender nonconforming adults. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18, 411–426.

Russell, G. M., Bohan, J. S., McCarroll, M. C., & Smith, N. G. (2011). Trauma, recovery, and community: Perspectives on the long-term impact of anti-LGBT politics. Traumatology, 17(2), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610362799.

Smart, L., & Wegner, D. M. (2000). The hidden costs of hidden stigma. The Social Psychology of Stigma, 220–242.

Stryker, S., Currah, P., & Moore, L. J. (2008). Introduction: Trans-, trans, or transgender? Women’s Studies Quarterly, 36(3/4), 11–22.

Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77.

Veldhuis, C. B., Drabble, L., Riggle, E. D., Wootton, A. R., & Hughes, T. L. (2018). “We won’t go back into the closet now without one hell of a fight”: Effects of the 2016 presidential election on sexual minority women’s and gender minorities’ stigma-related concerns. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 15(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0305-x.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Trans Health Community Advisory Board who assisted with this project for their time, feedback, and dedicated involvement. We also would like to thank the participants who took part in this research for their time and effort. We dedicate this work to Aimee Stephens who fought until her death for protections in our community. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F32DA038557.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Price, S.F., Puckett, J. & Mocarski, R. The Impact of the 2016 US Presidential Elections on Transgender and Gender Diverse People. Sex Res Soc Policy 18, 1094–1103 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00513-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00513-2