Abstract

Introduction

The present study examined father-–child relationships, parenting quality, and child psychological adjustment in 35 gay single father surrogacy families, 30 heterosexual single father surrogacy families, 45 gay two-father surrogacy families, and 45 heterosexual two-parent IVF families, when children were aged 3–10 years.

Methods

In each family, fathers were administered standardized questionnaires and interviews, and participated in three video-recorded observational tasks with their child. Teachers and a child psychiatrist further rated child adjustment.

Results

The only differences across family types indicated greater parenting stress in gay and heterosexual single fathers. Irrespective of family type, lower sensitivity and supportive parenting predicted greater father-reported child internalizing problems; whereas lower rough-and-tumble play quality and sensitivity, greater negative parenting and parenting stress, and the child male gender predicted greater father-reported child externalizing problems. In teachers’ ratings, the child female gender was associated with greater child internalizing problems, whereas greater negative parenting, lower rough-and tumble play quality, and the child male gender were associated with greater child externalizing problems.

Conclusions

The results confirm that the adjustment of children born to gay and heterosexual single fathers through surrogacy is more a function of family processes than family structure.

Policy Implications

The results enable practitioners to develop an informed view of the influence of assisted reproduction on the adjustment of children born to single fathers through surrogacy. In this vein, it is empirically unfounded for policymakers to consider children born to single fathers through surrogacy at risk of developing psychological problems, as well as to continue to ban single men from accessing fertility treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The proportion of children living in single father households varies considerably across countries, but recent regional statistics have demonstrated a rise in the number of single father families globally over the past 50 years (Eurostat, 2019). In Italy, where the present research was conducted, the exact number of single fathers is not available; however, according to the most recent official statistics of the European Union, single father families represented 2.8% of all European households in 2018 (Eurostat, 2019). In line with Golombok’s findings for single mother families (Golombok, 2015), single father families may be formed in a number of ways. The majority are likely formed following parental separation or divorce, or—less commonly—following the death of the mother, when the mother lacks interest in parenting or loses custody due to neglect or abuse, or when children actively seek to live with their father (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Coles, 2015). Very recently, so-called single fathers by choice have emerged. Such fathers are heterosexual, gay, or bisexual men who actively elect to parent alone. The demographically small, but growing, family form that such men comprise may be achieved through adoption or surrogacy—the practice whereby a woman (the “surrogate”) bears a pregnancy for the intended parent(s) with the intention of handing over the resulting child. The present study involved gay and heterosexual single fathers who had children through surrogacy (Carone, Baiocco, & Lingiardi, 2017b).

Policies on and access to assisted reproductive technology for single men vary between countries, according to the law, with some countries prohibiting single men access to these services (e.g., Italy, Norway, France) and others leaving decision-making around access largely up to clinicians (e.g., California, the UK). This is in spite of the ethical call to allow all persons access to fertility services, regardless of marital status or sexual orientation (De Wert et al., 2014). In Italy, surrogacy is banned to everyone and thus people who wish to have children through this path must turn to transnational surrogacy. In the particular case of single father families through surrogacy, a frequently held assumption in the public debate is that the combination of surrogacy and a single father may harm children due to the absence of a mother from the outset (Lingiardi & Carone, 2016). It is thus intuitively evident that gay and heterosexual single father families through surrogacy are situated, to different degrees, in a heteronormative context, in which it is contended that two parents are desirable for children to flourish and that a mother is an essential figure in child development (Scandurra et al., 2019).

Such assumptions particularly apply to Italy, which is bound by traditional family values and the widespread belief that conception without the use of assisted reproductive technologies is central to children’s adjustment (Ioverno et al., 2018). However, these assumptions are also prevalent in many other countries that are reluctant to guarantee equal access to fertility services (De Wert et al., 2014). Insofar as societal attitudes toward diverse family forms and contextual factors influence the development of positive parent–child relationships, parental competencies, and child adjustment (Armesto, 2002), it is paramount for researchers to study the implications of children being born through surrogacy and being raised by a gay or heterosexual single father. Such research is needed to inform the public dialogue on these emerging new family forms and to ground policies relating to the regulation of single parenthood and assisted reproduction in empirical research.

From a theoretical perspective, it is relevant that single father families offer the unique opportunity to assess the quality of fathers’ involvement with their children as primary and, presumably, sole caregivers. To date, parenting research has evaluated father–child interaction mainly during rough-and-tumble play, perpetuating the assumption rooted in mother-father families that fathers mainly provide economic support and interact with their children in a “rough” way, whereas mothers mainly provide sensitive responding and emotional support to their children’s expressions of distress (Cabrera, Volling, & Barr, 2018). However, these views are inaccurate and do not reflect the experiences of contemporary families (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth, & Lamb, 2000); furthermore, they are clearly inapplicable to single father families. It follows that single fathers further challenge researchers in identifying the best approach to measuring father–child relationships in order to capture the types of activities in which single fathers and their children engage, and the extent to which these activities are associated with child development (Volling & Cabrera, 2019).

Research on Single Parent Families Created by Assisted Reproduction

Research has yet to address the quality of parent–child relationships and parenting, as well as child adjustment, in gay and heterosexual single father families through surrogacy. To date, research on single parents through assisted reproduction has focused exclusively on single mothers through donor insemination (DI) (Chan, Raboy, & Patterson, 1998; Golombok, Tasker, & Murray, 1997; Golombok, Zadeh, Imrie, Smith, & Freeman, 2016; MacCallum & Golombok, 2004; Murray & Golombok, 2005a, 2005b). Murray and Golombok (2005a) compared 27 single mother DI families with 50 married DI families on mothers’ psychological wellbeing and the quality of the mother–child relationship when the child was 1 year old. Single DI mothers showed lower levels of mother–child interaction and lower levels of sensitive responding toward their infant than did married DI mothers, possibly due to the presence of a partner, which allowed the married mothers more time with their baby. At a follow-up 1 year later (Murray & Golombok, 2005b), the mother–child relationship was positive in both family types, but the single mothers showed greater joy and less anger toward their child, and the children of single mothers were reported to show fewer emotional and behavioral problems than those of married mothers.

Another recent study by the same research group (Golombok et al., 2016) found that, when children were aged 4–9 years, single mother DI families and mother-father DI families did not differ in parenting quality (apart from lower mother–child conflict in the former group) or child adjustment. Rather, regardless of family type, the factors associated with children’s psychological problems were parenting stress, perceived financial difficulties, and the child’s male gender. Of relevance, these findings echo those of Chan et al. (1998), who compared 21 lesbian single DI mother families and 9 heterosexual single DI mother families with 34 lesbian two-mother DI families and 16 mother-father DI families, all with children aged 7 years. In the study, child adjustment was found to be unrelated to family structure (i.e., parents’ sexual orientation and number of parents in the household), but correlated with parenting stress and, in the two-parent families, interparental conflict and couple satisfaction.

Single father surrogacy families and single mother DI families share challenges related to the need for the parents to come to terms with their concerns about single parenthood (relating to, e.g., their children getting teased about their family type or their children’s lack of a second parent), to face the burden of parenting alone, and to explain the assisted conception to their children (Carone et al., 2017b; Jadva, Badger, Morrissette, & Golombok, 2009). Yet, these two groups also differ in several respects. First, in Italy—and more widely in Western culture—a fundamental conviction prevails that a mother is essential for the healthy psychological development of children (Lingiardi & Carone, 2016; Scandurra et al., 2019). Second, a parallel belief is that fathers do not engage in hands-on parenting (Cabrera et al., 2018), following social norms relating to gender roles. Third, single fathers through surrogacy are more likely unique in terms of their income and thus less likely to experience financial hardship relative to single mothers through DI (Coles, 2015), given the higher cost of the surrogacy procedure.

Fourth, surrogacy conception may raise more concerns than DI with respect to the psychological effects (to the children) of being born to a woman (the surrogate) who conceived the children with the deliberate intention of relinquishing them to other parents—especially if the surrogate is also the genetic mother and money has changed hands (Golombok, 2015; Jadva, 2016). Finally, when surrogacy is pursued abroad (as is the case for Italian single fathers), the large geographical distance between the father and the surrogate may have a detrimental effect on the expectant single father’s emotional responses and his chance to bond with the developing foetus; it may also put additional psychological strain on him in relation to the pregnancy (Carone, Baiocco, & Lingiardi, 2017a; Ziv & Freund-Eschar, 2015). Considering these differences, it cannot be assumed that findings relating to single mother DI families necessarily also apply to single father surrogacy families.

Research on Father-Headed Families Created by Surrogacy

Single father surrogacy families have several commonalities with gay two-father surrogacy families, insofar as, in both family arrangements, children are conceived through surrogacy and are raised with no mother from the outset. Prior evidence with gay two-father surrogacy families indicates that this family type is not tied to children’s poor psychological adjustment, but that indeed external stigmatization is (Carone, Lingiardi, Chirumbolo, & Baiocco, 2018; Golombok et al., 2018; Green, Rubio, Rothblum, Bergman, & Katuzny, 2019; Patterson, 2017). Nonetheless, although single father and two-father families both lack a mother and share the surrogacy conception, an essential difference is that the children of gay partnered fathers grow up with two parents instead of one, and the shared parenting responsibility in this family form may reduce stress for the fathers and the child, alike (Ostberg & Hagekull, 2000).

Of note, some differences also exist within single father families based on the father’s sexual orientation, which may be heterosexual or gay. If heterosexual single fathers through surrogacy re-partner in the future, in fact, they do so with a mother figure; conversely, gay single fathers do not. Furthermore, before undertaking surrogacy, heterosexual single fathers may have the option of conceiving and raising children through different paths (e.g., adoption, conception within a heterosexual relationship), whereas gay single fathers have no authentic choice due to their non-heterosexual orientation and the ban on adoption for single people in Italy; this suggests that the motivations for surrogacy are quite different for these two groups of single fathers (Carone et al., 2017b). Finally, children of heterosexual single fathers do not have to cope with their fathers’ homosexuality and with potential subsequent teasing from peers, both of which have been abundantly shown to affect quality of life and impair social development (Bos & Gartrell, 2010; Bos & van Balen, 2008). That said, both the future prospects of children of single fathers and the differences that may or may not exist between gay and heterosexual single father families require further investigation.

The Present Study

The present study was a multi-method and multi-informant investigation of father–child relationships, parenting quality, and child psychological adjustment in gay and heterosexual single father surrogacy families with children aged 3–10 years. The choice to focus on this age range was guided by several factors, including the small, though growing, number of gay and heterosexual single father surrogacy families worldwide (for a similar approach with emerging new family forms, see, e.g., Bos, van Balen, van den Boom, & Sandfort, 2004; Carone et al., 2018; Golombok et al., 2016, 2018; Green et al., 2019). Most notably, at the age of 3 years, Italian children begin kindergarten and encounter peers with different family types. Furthermore, the upper age limit of age 10 was chosen to optimize the sample size while ensuring the appropriateness of the measures across the age range.

The study was framed by the family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 1997), which states that development results from the transactional regulatory processes of the dynamic systems in which individuals are embedded, including broader systems outside the family (e.g., socio-cultural context). Given the interdependence of family subsystems (e.g., parents, children), the importance of exploring whether—and to what extent—changes occurring in one subsystem are likely to impact functioning in another is particularly appropriate when examining factors (e.g., family structure vs. family processes) associated with child adjustment in single father surrogacy families.

The following two hypotheses were tested:

-

1.

Single father surrogacy families, regardless of the father’s sexual orientation, would face greater difficulties in relation to parenting quality, the father–child relationship, child psychological adjustment, and fathers’ parenting stress and psychological state than the comparison groups of gay two-father surrogacy families and mother-father IVF families. Although existing research suggests that neither single motherhood (Chan et al., 1998; Golombok et al., 1997, 2016; Lansford, Ceballo, Abbey, & Stewart, 2001; Murray & Golombok, 2005a, 2005b) nor surrogacy conception in gay and heterosexual two-parent families (Baiocco, Carone, Ioverno, & Lingiardi, 2018; Carone et al., 2018; Golombok, 2015, 2018; Green et al., 2019) nor the fathers’ non-heterosexual orientation (e.g., Farr, 2017; Fedewa, Black, & Ahn, 2015; Patterson, 2017) have a negative influence on parent and child outcomes, no study has been conducted thus far on single father families through surrogacy, which are characterized by the simultaneous presence of single parenthood, parents’ male gender (and non-heterosexual orientation, in the case of gay single fathers), and surrogacy conception. Furthermore, in line with the family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 1997), consideration of the broader Italian socio-cultural context is especially relevant in guiding our hypothesis, as gay and heterosexual single father surrogacy families must navigate a particularly complicated and sometimes hostile environment in relation to their family structure (Lingiardi & Carone, 2016). In the same vein, as all children in this study had already transitioned to kindergarten or primary school, all were being confronted—to some degree—with their family diversity and reactions to this from the outside world. If the outcomes found by research with single mother families through DI, gay two-father surrogacy families, and heterosexual two-parent surrogacy families, living in different socio-cultural contexts from Italy, can be further extended to Italian gay and heterosexual single father families is thus unknown.

-

2.

Once parenting quality, fathers’ sensitivity, father–child mutuality during interaction, the quality of rough-and-tumble play, parenting stress, and fathers’ psychological state will be taken into account, such family processes would better explain variations in child adjustment than would family type. This hypothesis is consistent with the broader literature on parenting in diverse families (e.g., Collins, Maccoby, Steinberg, Hetherington, & Bornstein, 2000; Goldberg & Gartrell, 2014; Golombok, 2015; Lamb, 2012), indicating that a more negative parenting quality and a more negative quality of parent–child relationship, as well as greater parenting stress and parents’ psychological problems, are associated with greater problems in child adjustment across all family types.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-five gay single father families through surrogacy and 30 heterosexual single father families through surrogacy were compared with 45 gay two-father surrogacy families and 45 mother-father IVF families, all with a child aged 3–10 years (n = 155). In families with more than one child in the relevant age range, the oldest child was studied. In mother-father IVF families the father’s data were used, whereas in gay two-father surrogacy families the genetic father’s data were used. In this way, the study controlled for the parent’s male gender, his genetic relationship with the child, and the use of IVF to conceive (i.e., all surrogacy arrangements had been gestational and thus all embryos had been created through IVF). The inclusion criteria for single fathers were as follows: (a) self-identified as gay or heterosexual, (b) decided to undertake parenting alone, (c) had not cohabited since the birth of the child, (d) had not been involved in a non-cohabiting relationship for longer than 6 months, and (e) had conceived the target child through surrogacy (similar criteria were used by Golombok et al., 2016). Gay partnered fathers were required to still be living with their partner and to have conceived their target child through surrogacy, whereas heterosexual partnered fathers were required to still be living with the child’s mother and to have conceived their target child through IVF (without a donor egg or donor sperm).

Single fathers were recruited using multiple strategies: first, the researchers posted online advertisements on the websites of single parent groups (n = 22, 33.9%); second, participants passed information about the study to their friends, colleagues, and acquaintances who fit the study criteria and/or disseminated information about the study through social media (n = 37, 56.9%); third, an association of same-sex parents distributed information about the study via their mailing list (n = 6, 9.2%). In addition, multiple sources were employed to recruit heterosexual partnered fathers: first, three of the largest fertility clinics that provide treatments to heterosexual couples in the area local to the research team (i.e., Rome and Milan) invited (by phone) potential families who met the study criteria and gave them mail contact of the research team (n = 16, 35.6%); second, the researchers posted online advertisements on the websites of parents who had conceived through assisted reproduction (n = 9, 20.0%); third, participants passed information about the study to their friends, colleagues, and acquaintances who fit the study criteria and/or disseminated information about the study through social media (n = 20, 44.4%). Finally, with regard to gay partnered fathers, 19 were recruited in the context of another study run by the research group (Carone et al., 2018) and an additional 26 gay partnered fathers were recruited by participating fathers who passed information about the study to other gay partnered fathers they knew who fit the study criteria. Due to the variable sources of recruitment employed for each family group, it was not possible to determine the exact number of fathers who were informed about the study; however, of the 210 fathers who contacted the research team, 155 agreed to take part, constituting a participation rate of 73.8%. Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology of Sapienza University of Rome. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from parents and teachers, whereas verbal assent was obtained from children. Data were collected between November 2016 and May 2019. Specifically, one researcher and two graduate students, all with expertise in developmental and family psychology, visited families at their homes. During these 3-h visits, single and partnered fathers were administered standardized questionnaires and participated in three video-recorded observational tasks with their child. Researchers were introduced to children explaining them that they were interested in their family life. In order to both facilitate familiarization between the child and the researchers and elicitate children’s views on their family relationships, the Apple Tree Family (Tasker & Granville, 2011) was used. A drawing of a tree and small cards in the shape of apples were offered to the child. The tree was presented as the child’s “family.” Each child was then asked to think about who belonged to their family and was invited to place an apple for each person on the sheet. Once they finished, children were asked which aspect they liked most of their family member. Following this home visit, due to time constraints and geographical distance from the research team, fathers were administered two standardized interviews over Skype; this data collecting method has been recognized as both commonplace in social science research and a viable methodological approach (Deakin & Wakefield, 2014).

To obtain an independent assessment of child problems, one teacher per family and a child psychiatrist also took part. After the home visit, parents were asked to pass an information sheet about the study to their child’s preschool/school teacher. The information sheet also contained the researchers’ contact details, which the teachers could use to gain more information about the study before deciding whether or not to participate. Parents were informed that they were not obliged to pass on the information, and teachers were informed that their responses would not be reported back to the child’s family or the school. Seven parents (i.e., 3 gay single fathers, 4 heterosexual single fathers) refused to involve their child’s teacher, whereas 30 teachers (i.e., 8 of children with gay single fathers, 6 of children with heterosexual single fathers, 6 of children with gay partnered fathers, and 10 of children with heterosexual partnered fathers) did not email back the questionnaires, constituting a final response rate of 76.1% (n = 118, of whom 112 were women).

Measures

Observed Father–Child Interaction

Within each family, each father–child dyad participated in a video-taped assessment of their interaction in “real time” during the Etch-A-Sketch task (Stevenson-Hinde & Shouldice, 1995). The Etch-A-Sketch is a drawing tool with two knobs on the front of the frame that allow users to draw vertically and horizontally, respectively. In the Etch-A-Sketch task, each dyad was asked to reproduce a picture of a house, with clear instructions that the child was to use one knob and the parent the other knob, without overlapping activity. Father–child interactions were coded using the Coding of Attachment-Related Parenting (CARP; O’Connor, Matias, Futh, Tantam, & Scott, 2013), which is a global measure of parent–child interaction quality derived from attachment theory. Reliability and validity data for the coding system have been reported in several samples (O’Connor et al., 2013; O’Connor, Woolgar, Humayun, Briskman, & Scott, 2018). The CARP places conceptual emphasis on patterns of sensitivity, emotional attunement, and bi-directional dyadic processes such as mutuality.

In the present study, the following two variables were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (no evidence) to 7 (pervasive/extreme evidence), with higher values indicating more positive behaviors throughout the interaction: (a) sensitive responding assessed the degree to which the fathers showed awareness of their child’s needs and sensitivity to his/her signals, promoted the child’s autonomy, adopted the child’s psychological point of view, and physically or verbally expressed positive emotion and warmth toward the child; and (b) mutuality reflected the degree to which the father and child in each dyad accepted and sought the other’s involvement in a joint activity, built on each other’s input and coordinated their efforts/actions while conducting a task together, maintained shared attention and fluid conversation, reciprocated positive affectionate behaviors, and maintained physical proximity/closeness when interacting with each other. To establish interrater reliability, approximately one-third of the videos (n = 38) were randomly selected and coded by an undergraduate student who was trained by the first author and was blind to family type. The intraclass correlations (ICCs) for sensitive responding and mutuality were .81 and .75, respectively. Disagreements between coders were discussed until a consensus was reached. Means and standard deviations of the two CARP scales are provided in Table 3.

Observed Rough-and-Tumble Play Quality

Each father–child dyad was asked to play two rough-and-tumble games: “Get-Up” and “Sock Wrestle” (Fletcher et al., 2013). Each game lasted 5 min. In the Get-Up game, fathers were instructed to lie on their back and, at the word “Go” from the group leader, to try to stand up while their child tried to hold them down. In the Sock Wrestle game, father and child played on their hands and knees, with each trying to get the other’s socks off without losing his/her own. Both games were played within the confines of a large square rug, with a small camcorder mounted on a tripod approximately 3 m away. A researcher instructed the father and child on the procedure of the two games and, after turning on the camera, left the room. Two independent coders rated the interactions using the RTP-Q scale (Fletcher et al., 2013).

This measure comprised items related to warmth, control, sensitivity, winning and losing, physical engagement, and playfulness, captured as both individual and dyadic behaviors. Five global narrative descriptions were developed to describe the quality of the interaction and behavior of the father and child (i.e., poor = 1, fair = 2, good = 3, very good = 4, and excellent = 5). The behaviors at each of the five levels of RTP quality were operationalized to form a 16-item scale and a specific rating level within each item (using 5-point Likert scales). These items captured the individual and dyadic affective states and behaviors of the father and child, including verbal and non-verbal behaviors. Each item was assessed for frequency and/or intensity, with higher ratings corresponding with increased frequency and intensity. Overall judgements about the presence of the behaviors, or “global ratings,” were used, because the primary research interest was not specific behaviors (i.e., micro-level analysis), but clusters of behaviors that, together, shaped the quality of the father–child interaction during the games (Fletcher et al., 2013). Scores obtained on the two tasks were averaged for each dyad and approximately one-third of the videos (n = 38) were randomly selected and coded by an undergraduate student who was trained by the first author and was blind to family type. Of note, videos referring to the father–child dyads that had already been coded with the CARP were excluded from the selection; furthermore, the second rater who coded the videos with the RTP-Q was different from the second rater who coded the videos with the CARP. The intraclass correlations (ICC) for the overall level of RTP quality was .78. Disagreements between coders were discussed until a consensus was reached. Following Fletcher et al. (2013), after the two tasks, fathers were asked whether the Get-Up and Sock Wrestle play interactions were more or less similar to their usual interactions with their child. Fathers indicated that there were no major differences between the video-taped play and regular play with their children. Means and standard deviations of the two RTP-Q scales are provided in Table 3.

Parenting Quality

Fathers completed the Parenting Quality Interview (Shlafer, Raby, Lawler, Hesemeyer, & Roisman, 2015) over Skype, which is a semi-structured interview designed to assess their individual parenting attitudes, beliefs, and practices. Specifically, fathers were asked to describe their ideal parent–child relationship and to supply examples of their parenting behaviors to support their stated views, as well as to describe their parenting experiences of providing support, affection, and setting limits. Each interview lasted approximately 1 h and was audio-recorded. The interview allowed the researcher to rate each variable according to a detailed standardized coding scheme described in an accompanying interview manual, rather than relying on parents’ self-report data. For the present study, the original English version of the interview measure was translated into Italian and back-translated into English to check for problems in the translation. A pilot version of the interview was administered to 16 parents (i.e., 4 for each family type) who were not involved in the study, and any questions that were reported as unclear were reworded. Parenting quality was assessed from the parenting interviews using six 7-point rating scales, including the following codes: (a) positive emotional connectedness, which concerned the father’s warmth toward the child and pleasure in being a parent; (b) parental investment/involvement, which described the father’s belief in the importance of being a parent and clear commitment to parenting; (c) parental confidence, which assessed the father’s sense of efficacy in the parental role; (d) hostile parenting, which represented the degree to which the father derogated or rejected the child throughout the interview; (e) parent–child boundary dissolution, which assessed role-reversal in the father–child relationship; and (f) coherence of parenting philosophy, which referred to the organization and consistency of the father’s parenting beliefs and practices. Ratings for all participants were completed by two independent coders, and interrater reliabilities (ICCs) were .76, .84, .78, .81, .82, and .88 for positive emotional connectedness, parental investment/involvement, parental confidence, hostile parenting, parent–child boundary dissolution, and coherence of parenting philosophy, respectively. Disagreements between coders were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Given that multiple indicators of parenting were assessed, to reduce overlap in variance and to retain greater power for the analyses, principal components analysis with oblimin rotation was used to create composite variables of positive and negative parenting. Oblimin rotation was chosen because there were theoretical and empirical reasons to expect correlation between the component factors. Principal components analysis indicated that a two-component structure accounted for the variability in the parenting interview ratings reasonably well: supportive parenting included positive emotional connectedness, parental investment/involvement, and coherence of parenting philosophy (α = .79), whereas negative parenting included hostile parenting and parent–child boundary dissolution (α = .76). Higher scores reflected greater supportive parenting and negative parenting. As in the original study (Shlafer et al., 2015), parental confidence significantly cross-loaded (< .20 difference in loadings) and was therefore dropped from further analysis. These two factors explained more than 60% of the variance in the items, with all factor loadings above .70. The correlation between supportive and negative parenting factors (r = − .38, p < .001) showed a moderate negative relationship.

Parenting Stress

Fathers completed the 36-item short form of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI-SF third edition; Abidin, 1990; for the Italian adaptation, see Guarino, Di Blasio, D’Alessio, Camisasca, & Serantoni, 2008) to assess their stress associated with parenting. Using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 [strongly disagree] to 5 [strongly agree]), they were asked to indicate the extent of their agreement or disagreement with statements describing them as stressed (e.g., “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent”) or describing the father–child relationship (e.g., “My child rarely does things for me that make me feel good”) or their child’s characteristics as difficult to manage (e.g., “My child reacts very strongly when something happens that my child doesn’t like”). In the present study, a total stress score was used, with higher scores reflecting greater parenting stress. The normal range for scores is within the 15th to 80th percentiles (Abidin, 1990). The instrument has been shown to demonstrate high internal consistency and good test–retest reliability after 1 year (Abidin, 1990). For the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

Fathers’ Psychological Adjustment

The Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983; Derogatis, 2001) comprises 18 items that evaluate fathers’ depressive, anxious, and somatic symptoms. Fathers were asked to rate the frequency with which they had experienced a list of symptoms (e.g., feeling no interest in things, feeling suddenly scared for no reason, feeling weak in parts of their body) within the past 7 days on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). For this measure, the Global Severity Index (GSI score) was used, with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological symptoms. The BSI-18 has been shown to demonstrate adequate to good internal consistency (Derogatis, 2001). The total normative score for the three scales used (i.e., somatization, depression, and anxiety) is 5.81 (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). For the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .79.

Children’s Psychological Adjustment (Father and Teacher Reports)

In each family, both the father and the child teacher completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997; for the Italian adaptation, see Tobia, Gabriele, & Marzocchi, 2013; Tobia & Marzocchi, 2018) to assess child adjustment over the last 6 months (e.g., internalizing domain: “Many worries, often seems worried”; externalizing domain: “Restless, overactive, cannot stay still for long”). Total scores of internalizing and externalizing problems were used, as recommended by Goodman, Lamping, and Ploubidis (2010) for the study of low-risk samples, with higher scores indicating greater psychological problems. For the parent version, scores of internalizing and externalizing problems of Italian children from a community sample of the same mean age of children in this study are 3.24 and 4.52 (Tobia & Marzocchi, 2018), whereas, for the teacher version, scores of internalizing and externalizing problems are 3.74 and 4.61, respectively (Tobia et al., 2013). For the present sample, Cronbach’s alphas for the parent- and teacher-rated internalizing problems were .83 and .79, respectively; Cronbach’s alphas for parent- and teacher-rated externalizing problems were .85 and .80, respectively.

Children’s Psychiatric Symptoms (Interview with Father and Psychiatric Ratings)

Fathers were also administered a portion of the Development and Well-Being Assessment interview (Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward, & Meltzer, 2000) over Skype to provide detailed descriptions of the symptoms displayed by their child over the prior 12 months in several psychiatric domains (e.g., anxiety, conduct disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, speech delay). Each interview lasted approximately 30 min and was audio-recorded. When definite symptoms were reported, open-ended questions and supplementary prompts were used to get parents to describe (in their own words) the contexts in which symptoms were shown, as well as their severity, frequency, precipitants, course, and impact on the child and the family. These descriptions were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer and rated by a child psychiatrist who was unaware of the nature of the study. The reliability between interviewer and psychiatrist ratings was high (ĸ = .80, p < .001). Psychiatric problems, when identified, were rated according to severity on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no disorder) to 1 (slight disorder) and 2 (marked disorder).

Analytic Plan

All analyses were performed using the statistical software R (R Development Core Team, 2018). Effects that were significant at p < .05 were interpreted. For all analyses, bootstrapping was used to understand the stability of the results within a larger simulated sample (n = 1000 families). To compare child outcomes and family processes across family types (hypothesis 1), six separate multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) were conducted with family type (gay single father family vs. heterosexual single father family vs. gay two-father family vs. heterosexual two-parent family) and child gender (boy vs. girl) as the between-subjects factors. Given significant differences between family types on number of children and annual household income, both variables were entered as covariates in all analyses. Of note, comparisons using the traditional null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) were further supplemented by Bayesian analyses, as the latter allow for a more robust examination of the null hypothesis than NHST (Dienes, 2011). A Bayes Factor (BF01) of 1–3 indicates anecdotal evidence, whereas a BF01 of 3–10 indicates substantial evidence for the null hypothesis (i.e., the data are 3–10 times more likely to support the null vs. alternative hypothesis) (Dienes, 2011).

To identify the likelihood that the data would detect what best explains children’s internalizing and externalizing problems (hypothesis 2), given a set of parameters (van de Schoot et al., 2014), several Bayesian multiple linear regression models were computed and compared using the total coefficient of determination (TCD; Bollen, 1989) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Schwarz, 1978). The TCD method shows the combined effect of variables on the dependent variables; the BIC method measures the efficiency of the parameterized model in terms of predicting data and, at the same time, penalizes the complexity of the model, wherein complexity refers to the number of unnecessary parameters. The higher the TCD (range 0–1), the more variance is explained; the lower the BIC, the better the model. As a consequence, the model with the highest TCD and lowest BIC can be said to best fit the data. Bayesian statistical inference was run with orthodox statistics in order to overcome the possible limitations of the small sample while maintaining predictive accuracy and preventing specific problems associated with NHST (i.e., falsification of the null hypothesis without any support for alternative hypotheses, lack of information on which data support the hypotheses, and comparison of non-nested models) (Dienes, 2011). This approach was useful in guiding the selection of covariates to be retained based on the best fit indices: models containing child age, father age, and annual household income as covariates were excluded as they fitted worse than the null model and the TCD was not significant. The set of investigated predictors of children’s internalizing and externalizing problems comprised family type (for analyses coded as “Number of parents [-1 = single fathers, 1 = partnered fathers] * Fathers’ sexual orientation [-1 = gay, 1 = heterosexual]”), sensitivity, mutuality, rough-and-tumble play quality, supportive parenting, negative parenting, parenting stress, father’s psychological state, and the interaction between family type and each of the family process variables. Child gender (coded as -1 = boy, 1 = girl) and number of children were also entered as covariates due to their significant associations with child outcomes. All variables were centered in advance, in order to reduce multicollinearity.

Results

Associations among children’s and fathers’ characteristics, child outcomes, and family process variables are displayed in Table 2, whereas descriptive analyses are displayed in Table 3.

Father–Child Relationships, Parenting, and Fathers’ Adjustment as a Function of Family Type

All the following factorial MANCOVAs were conducted with family type and child gender as the between-subjects factors and number of children and annual household income as covariates. Regarding the quality of observed father–child interaction (fathers’ sensitivity, mutuality, and rough-and-tumble play), the main effect for child gender was significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.87; F(3,143) = 6.95, p < .001, ηp2 = .13, indicating that father–male child dyads showed both greater mutuality, F(1,145) = 15.77, p < .001, ηp2 = .10, and rough-and-tumble-play quality, F(1,145) = 10.77, p = .001, ηp2 = .07, than father–female child dyads, and that fathers were more sensitive while interacting with their male children, F(1,145) = 4.92, p = .028, ηp2 = .03. Conversely, neither the main effect for family type, Wilks’ λ = 0.95; F(9,348) = 0.84, p = .582, ηp2 = .02, nor the interaction between family type and child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.96; F(9,348) = 0.63, p = .773, ηp2 = .01, were significant. With respect to covariates, annual family income was not significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.99; F(3,143) = 0.55, p = .652, ηp2 = .01, whereas number of children had a significant effect, Wilks’ λ = 0.92; F(3,143) = 3.94, p = .010, ηp2 = .08.

Findings related to supportive parenting (emotional connectedness, parental investment, coherence of parenting philosophy) indicated that gay single fathers, heterosexual single fathers, gay partnered fathers, and heterosexual partnered fathers did not differ in their levels of supportive parenting dimensions, Wilks’ λ = 0.99; F(9,348) = 0.23, p = .990, ηp2 = .01. Likewise, neither the main effect of child gender, Wilks’ λ = 1.00; F(3,143) = 0.05, p = .987, ηp2 = <.01, nor the interaction between family type and child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.90; F(9,348) = 1.66, p = .097, ηp2 = .03, were significant. With respect to covariates, neither annual family income, Wilks’ λ = 0.98; F(3,143) = 0.97, p = .409, ηp2 = .02, nor number of children had a significant effect, Wilks’ λ = 1.00; F(3,143) = 0.13, p = .945, ηp2 = < .01.

Likewise, no differences were found between gay single fathers, heterosexual single fathers, gay partnered fathers, and heterosexual partnered fathers in relation to negative parenting (hostile parenting, parent–child boundary dissolution), Wilks’ λ = 0.96; F(6,288) = 1.00, p = .423, ηp2 = .02. Furthermore, neither the main effect of child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.99; F(2,144) = 0.95, p = .389, ηp2 = .01, nor the interaction between family type and child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.94; F(6,288) = 1.53, p = .167, ηp2 = .03, were significant. With respect to covariates, neither annual family income, Wilks’ λ = 0.99; F(2,144) = 1.11, p = .331, ηp2 = .02, nor number of children had a significant effect, Wilks’ λ = 0.97; F(2,144) = 2.52, p = .084, ηp2 = .03.

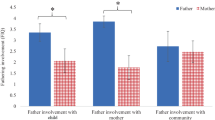

Finally, regarding fathers’ psychological adjustment (parenting stress and fathers’ psychological state), a significant main effect for family type was found, Wilks’ λ = 0.77; F(6,288) = 6.72, p < .001, ηp2 = .12, reflecting greater parenting stress in gay single fathers compared to gay partnered fathers (p = .004) and heterosexual partnered fathers (p = .001), as well as in heterosexual single fathers compared to gay partnered fathers (p = .005) and heterosexual partnered fathers (p = .001). However, there was no significant difference on the basis of child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.98; F(2,144) = 1.86, p = .160, ηp2 = .03, or any interaction between family type and child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.98; F(6, 288) = 0.47, p = .833, ηp2 = .01. With respect to covariates, number of children was significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.83; F(2,144) = 15.21, p < .001, ηp2 = .17, whereas annual household income was not significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.99; F(2,144) = 1.10, p = .337, ηp2 = .02.

When the analysis was repeated without covariates, the same significant and non-significant effects were found in all analyses. Alongside, Bayes factors supported all previous significant and non-significant results obtained using NHST (Table 3).

Child Adjustment as a Function of Family Type

Two separate factorial MANCOVAs with family type and child gender as between-subjects factors and number of children and annual household income as covariates for the fathers’ and teachers’ reports of internalizing and externalizing problems were carried out. With respect to child adjustment as reported by fathers, family type was not significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.99; F(6,288) = 0.34, p = .915, ηp2 = .01, indicating that children of gay single fathers, heterosexual single fathers, gay partnered fathers, and heterosexual partnered fathers did not differ in their levels of reported internalizing and externalizing problems. However, child gender was significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.88; F(2,144) = 9.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .12, reflecting greater externalizing problems in boys, F(1,145) = 8.44, p = .004, ηp2 = .06, and greater internalizing problems in girls, F(1,145) = 4.21, p = .042, ηp2 = .03. These patterns were consistent across family types, since the interaction between family type and child gender was not significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.97, F(6,288) = 0.63, p = .707, ηp2 = .01. Finally, while number of children had a significant effect, Wilks’ λ = 0.94, F(2,144) = 4.95, p = .008, ηp2 = .06, annual household income did not, Wilks’ λ = 0.98, F(2,144) = 1.24, p = .293, ηp2 = .02.

When teachers’ reports of child internalizing and externalizing problems were entered into the analyses, both family type, Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(6,214) = 0.15, p = .988, ηp2 < .01, and the interaction between family type and child gender, Wilks’ λ = 0.98, F(6,214) = 0.46, p = .838, ηp2 = .01, remained non-significant. Conversely, child gender was significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.79; F(2,107) = 14.35, p < .001, ηp2 = .21, reflecting greater internalizing problems in girls, F(1,108) = 11.02, p = .001, ηp2 = .09, and greater externalizing problems in boys, F(1,108) = 10.33, p = .002, ηp2 = .09. Finally, number of children tended toward non-significance, Wilks’ λ = 0.95; F(2,107) = 2.75, p = .069, ηp2 = .05, whereas annual household income was not significant, Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F(2,107) = 0.30, p = .741, ηp2 = .01. Bayes factors supported all previous significant and non-significant results obtained using NHST (Table 3).

Finally, the child psychiatrist identified slight adjustment difficulties among three (8.6%) children of gay single fathers (two with conduct disorders, one with speech delay), two children (6.7%) of heterosexual single fathers (one with a conduct disorder, one with speech delay), two (4.4%) children of gay partnered fathers (one with a conduct disorder, one with emotional problems) and three (6.7%) children of heterosexual partnered fathers (two with conduct disorders and one with speech delay). Furthermore, only one (2.2%) child of heterosexual partnered fathers showed marked speech delay. The psychiatrist’s ratings showed no differences in the proportion of children with a psychiatric disorder between family types, according to Fisher’s exact test (p = .86).

Family Processes Versus Family Type for Child Outcomes

To examine the most significant variables (family type vs. family processes) and the extent to which these affected children’s internalizing and externalizing problems, four separate regression analyses were computed and compared using fathers’ and teachers’ scores. Given the relatively limited sample size, to preserve statistical power, covariates were introduced separately and then retained in the full models only when they demonstrated significant predictive value in isolation. This choice was further substantiated by model fit indices: covariates that produced worse model fit indices were dropped from further analyses (i.e., models containing fathers’ age, child’s age, and annual household income were excluded). Fit indices and the details of the models used are reported in Table 4. First, family type was tested as the main predictor with child gender and number of children as covariates (model 1); next, fathers’ sensitivity, mutuality, rough-and-tumble play quality, supportive parenting, negative parenting, parenting stress, and psychological state were included as additive terms (model 2); finally, the interactions between family type and each family process (model 3) were introduced.

With respect to fathers’ reports of children’s internalizing problems, the total variance explained by the introduction of family processes into the model (model 2) was six times higher (i.e., TCD = .25, BIC = 602.60, n = 155) than that explained by family type and covariates, only (model 1) (i.e., TCD = .04, BIC = 611.96, n = 155). When the interactions between family type and each family process were further considered (model 3), the model did not show better fit indices than the model 2 (i.e., TCD = .26, BIC = 627.85, n = 155). Therefore, following the convention that the model with the highest global variance (see TCD, Bollen, 1989) and the lowest BIC (Schwarz, 1978) best contributes to explaining the data, model 2 resulted as the best model, explaining 25% of the variance in children’s internalizing problems. Specifically, in this model, greater children’s internalizing problems were associated with lower fathers’ sensitivity, β = − .24, p = .009 and, marginally, lower supportive parenting, β = − .15, p = .052. Conversely, family type, β = − .04, p = .608, child gender, β = .12, p = .144, annual household income, β = .08, p = .277, observed mutuality, β = − .14, p = .146, rough-and-tumble play quality, β = .03, p = .758, negative parenting, β = .05, p = .567, parenting stress, β = .11, p = .227, and father’s psychological state, β = .11, p = .141, showed no significant effects.

When father-reported children’s externalizing problems were considered, the total variance explained by the introduction of family processes in the model (model 2) was more than five times higher (i.e., TCD = .44, BIC = 676.18, n = 155) than that explained by family type and covariates only (model 1) (i.e., TCD = .08, BIC = 724.66, n = 155). Model 2 remained the best model, explaining 44% of the variance in children’s externalizing problems, even when the interactions between family type and each family process were further considered (model 3) (i.e., TCD = .43, BIC = 706.75, n = 155). Specifically, the factors significantly associated with greater children’s externalizing problems in model 2 were child male gender, β = − .32, p < .001, lower rough-and-tumble play quality, β = − .30, p < .001, lower fathers’ sensitivity, β = − .20, p = .011, greater negative parenting, β = .15, p = .032, and greater parenting stress, β = .16, p = .041. Conversely, there were no significant effects for family type, β = − .07, p = .242, annual household income, β = .04, p = .564, observed mutuality, β = − .05, p = .508, supportive parenting, β = − .08, p = .245, and fathers’ psychological state, β = .04, p = .502.

Of relevance, unlike the regression models predicting father-reported child adjustment problems, regression models using teachers’ reports found that internalizing problems were only associated with the child female gender, β = .35, p = .001, whereas externalizing problems were associated with the child male gender, β = − .42, p < .000, negative parenting, β = .23, p = .008, and rough-and-tumble play quality, β = − .33, p = .000. In all analyses, the effects were unlikely to have arisen due to multicollinearity, as all predictors showed tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values of collinearity within acceptable levels (> 0.50 and < 2.00, respectively; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2012). A bootstrapping simulation indicated that repeated samples with n = 1000 ratings would be unlikely to detect different statistically (non-)significant effects from those detected by the present sample for any of the developmental outcomes.

Discussion

The present study used a multi-method and multi-informant approach to examine the adjustment of children born through surrogacy and raised by gay or heterosexual single fathers, in comparison to the adjustment of children of gay partnered fathers through surrogacy and heterosexual partnered fathers through IVF, respectively. The findings indicate that, across family types, children’s internalizing and externalizing difficulties were in the normal range and very low in relation to the cut-off points for clinical problems as found in Italian community samples (Tobia & Marzocchi, 2018). Alongside, both single and partnered fathers, regardless of their sexual orientation, were well adjusted and characterized by similarly high and low levels of supportive and negative parenting, respectively, as assessed by the interview, as well as by similarly high levels of parental sensitivity, mutuality, and rough-and-tumble play quality, as assessed by direct observation.

Specifically, contrary to our first hypothesis, no differences were found across the four family types on parenting quality, fathers’ observed sensitivity and rough-and-tumble play quality, father–child mutuality, child psychological adjustment, and fathers’ psychological state. However, differences were noted in relation to parenting stress, which was reported as higher in gay and heterosexual single fathers relative to their partnered counterparts. A closer inspection lends more insight to this finding. Despite the differences found between family types (single vs. partnered fathers), the parenting stress scores of both groups were under the cutoff for clinical significance (> 75th percentile) and lower than the scores of the normative sample (Guarino et al., 2008). Second, central to the definition of parenting stress “is the parent’s perceptions of having access to available resources for meeting the demands of parenthood […] relative to the perceived demands of the parenting role” (Deater-Deckard, 1998, p. 315). Thus, single fathers’ reports of parenting stress might reflect a greater mismatch between their expectations and their perceptions of available resources (e.g., less knowledge, less emotional, and instrumental support), relative to partnered fathers.

In this vein, although the present study did not assess fathers’ social support system and preparation for parenthood, a preliminary study with a small sample of Italian single fathers (Carone et al., 2017b) indicated that they were greatly concerned with their lack of resources (e.g., lack of acceptance from one’s family of origin, lack of support from friends, and lack of support at work). Third, the hostile social climate in Italy toward single fatherhood through surrogacy and the lack of social policies supporting diverse family forms and parenting (Ioverno et al., 2018; Lingiardi & Carone, 2016; Scandurra et al., 2019) might have further contributed to this group’s negative perception. Finally, although prior research by Patterson (Chan et al., 1998) and Golombok (Golombok et al., 1997, 2016; Murray & Golombok, 2005a, 2005b) has not found single mothers to be more stressed than partnered mothers, other evidence suggests that the number of parents in the household does affect parenting stress, with single parents more likely than those in two-parent households to face a heavier workload and to experience more child caretaking tasks; both of these things may increase parenting stress (Ostberg & Hagekull, 2000).

The ratings of both fathers and teachers, as well as the child psychiatrist, indicated that child adjustment was unrelated to family type. This result comes in line with the abundant evidence found in prior research on emerging new family forms (i.e., family forms that differ from the heterosexual two-parent family with children conceived through sexual intercourse, such as gay two-father surrogacy families, lesbian two-mother and single mother families through DI, and adoptive gay and lesbian parent families, among others) (e.g., Baiocco et al., 2018; Bos & Gartrell, 2010; Carone et al., 2018; Farr, 2017; Farr, Bruun, & Patterson, 2019; Gartrell, Bos, & Koh, 2018; Golombok et al., 2016, 2018; Green et al., 2019).

The fact that single fathers had actively decided to parent alone and embark on a particularly demanding path to parenthood despite the legal ban on domestic surrogacy in Italy and the fairly negative social attitudes toward unconventional family forms (Ioverno et al., 2018) may have contributed to the positive outcomes found in their children. It is reasonable to speculate that these fathers’ high motivation, commitment to parenthood, and internal resilience—or a combination of these factors—may have influenced their children’s positive adjustment. By the same token, because elective fatherhood and surrogacy conception are not common among single men—particularly in socio-cultural contexts bounded by traditional family values such as Italy (Ioverno et al., 2018; Lingiardi & Carone, 2016)—the single fathers in this study may have experienced their parenthood as a triumph over widespread heterosexist messages that the mother-father family is the best environment in which to raise children; with this attitude, they may have been more likely to support their children’s adjustment. Earlier research with gay two-father families indicates that this may be the case (Carneiro, Tasker, Salinas-Quiroz, Leal, & Costa, 2017; Erez & Shenkman, 2016; Shenkman & Shmotkin, 2014; van Rijn-van Gelderen et al., 2017).

As hypothesized, variations in child adjustment were better explained by family processes. Specifically, fathers reporting greater internalizing problems in their children showed lower supportive parenting and sensitivity during parent–child interactions. This finding has been well documented in parenting research with heterosexual two-parent families, which has shown that parents who are more aware of their child’s needs, more able to perceive and respond to their child’s cues, more promoting of their child’s autonomy and accepting of their psychological points of view, more physically and verbally expressive of warmth toward their child, and less prone to show rejection are more likely to detect and alleviate their child’s symptoms of anxiety and depression, should they be present (Kok et al., 2013; Lansford et al., 2018; McLeod, Wood, & Weisz, 2007). These parenting behaviors are thought to mitigate against the development of anxiety in children because, in the context of supportive and sensitive parenting, children may learn to regulate their emotions, including those related to anxiety-provoking situations, and be reassured that parental assistance is available when needed (Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003).

Generally, such research findings have been found to apply more directly to mothers than to fathers. This is typically explained by the fact that mothers tend to spend more time with their children than fathers and are thus more knowledgeable of their children’s difficulties and involved in their care (Lansford et al., 2018). In light of the family composition in the present sample (only fathers with no mothers in three of the four groups), it may be that what has previously been interpreted as an effect of motherhood (vs. fatherhood) in heterosexual two-parent families is instead an effect of being a primary (vs. secondary) caregiver. This is a novel finding of the present study. By the same token, given that the effects of supportive parenting and sensitivity on internalizing problems were found to be consistent in the group of IVF partnered fathers (who co-parented with their child’s mother), it may be that conception through assisted reproduction (i.e., surrogacy and IVF) enhances a high commitment to and involvement with children in all fathers, regardless of the presence of the mother in the home.

As supported by the parenting literature, the present research found greater father-reported externalizing problems in children to be associated with family processes such as greater negative parenting and parenting stress, and lower sensitivity and rough-and-tumble play quality (Collins et al., 2000; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004), as well as with the child male gender (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987). Given the variety of fathers included in this study, the fact that sensitivity and rough-and-tumble play quality were significantly associated with children’s externalizing problems has important methodological implications, suggesting the importance of including both factors in studies measuring fatherhood and child development (Volling & Cabrera, 2019). This finding further aligns with research on heterosexual two-parent families showing that fathers’ sensitive play, and not only rough-and-tumble play, uniquely contributes to child adjustment (John, Halliburton, & Humphrey, 2013; Menashe-Grinberg & Atzaba-Poria, 2017; Notaro & Volling, 1999). With respect to other family processes associated with children’s externalizing problems, research supports the direct effects between negative parenting and parenting stress on externalizing behaviors (McKee, Colletti, Rakow, Jones, & Forehand, 2008), as found in this study; however, transactional frameworks indicate that parenting and child outcomes are likely to have reciprocal links over time (Deater-Deckard, 1998).

With respect to teachers’ reports, the present study confirmed the effects of child male gender, negative parenting, and rough-and-tumble play quality on children’s externalizing problems, but not those of sensitivity and parenting stress; furthermore, only the child female gender was found to be a significant predictor of internalizing problems. Whether these findings were influenced by informant effects cannot be ruled out (Rescorla et al., 2013). It is relevant, however, to note that the reports from fathers and teachers reflected different settings (i.e., home and school) in which the children interacted, and the children may have shown different behaviors between these settings (Achenbach et al., 1987). In the same vein, from a family systems perspective (Cox & Paley, 1997), parenting behaviors may be understood to have a closer association with child behaviors observed at home and within the family, rather than at school. That said, most teachers (95%) involved in the present study were women. For this reason, future studies should investigate whether the fathers’ and teachers’ different perceptions of child internalizing problems reflected the different socialization of men and women, resulting in fathers (men) being less capable of detecting their children’s internalizing problems than teachers (mostly women) (a similar hypothesis has been reported by Golombok et al., 2018 and Carone et al., 2018 to explain differences in gay fathers’ and lesbian mothers’ perceptions of children’s internalizing problems).

Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths of the study should be acknowledged. First, the multi-method (drawing on interviews, observations, and questionnaires) and multi-informant (involving parents, children, teachers, and a child psychiatrist) design helped to minimize socially desirable responding, limiting the influence of the observed subject’s tendency to “fake good” (Aspland & Gardner, 2003). Second, a criticism of research on diverse family forms relates to statistical power (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010), but such a critique could not be leveled against the present findings. Following Cohen’s recommendations (1988), power analyses revealed that the sample size was large enough to generate sufficient power to detect at least medium effect sizes with an alpha of .05. Specifically, in regression analysis with 10 predictors of father-reported and teacher-reported child adjustment problems (model 2), power reached .92 and .80, respectively, for medium effects, but only .16 and .13, respectively, for small effects. Third, a bootstrapping simulation revealed that a larger sample size would be unlikely to reveal differences in child or parent outcomes as a function of family type. Finally, considering the demographic characteristics of the participants (male, highly educated, and relatively affluent parents; long-awaited children), in many respects, our study of single father families enabled an examination of the joint impact of male and single parenthood and surrogacy conception on child development in the absence of risk factors such as parental conflict, economic hardship, and parental mental health problems, which usually occur in single parent families formed in the aftermath of divorce or the death of the co-parent (Coles, 2015; Golombok, 2015).

However, the present study is not without limitations. As is often the case with initial studies of minority and hidden groups, the sample of single father families was not large and non-random sampling techniques were used for recruitment. Furthermore, it is difficult to precisely estimate the representativeness of the volunteer sample of 35 gay and 30 heterosexual single father families through gestational surrogacy to the general population of single fathers through surrogacy, though their very high annual household income and the prohibitive cost of surrogacy suggest that persons who take this path to parenthood comprise a demographically homogeneous group (Carone et al., 2017b). Finally, a perfect comparison between groups would have required heterosexual partnered fathers to have also conceived through surrogacy. This was not possible due to recruitment problems, likely related to the extremely hostile societal attitudes in the Italian context toward surrogacy (Lingiardi & Carone, 2016), which may have fostered reluctance in heterosexual parents through surrogacy to participate in the research and disclose their method of conception. Conversely, even if this hostility also concerns single fathers and gay partnered fathers, these groups might have been more motivated to participate in the research in order to contribute to empirical findings on their specific family forms given the lack of equal access to assisted reproduction for same-sex couples and single persons in Italy. However, it is relevant to note that surrogacy conception in single father and gay two-father families implied a form of IVF, and all family types were likely to experience stress related to their use of assisted reproduction and the social stigma attached to this method of conception.

Implications for Policy and Future Directions

The investigation of factors associated with child adjustment in emerging new family forms has been a sustained research focus over past decades (for a review, see, Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Fedewa et al., 2015; Goldberg & Gartrell, 2014; Golombok, 2015; Lamb, 2012; Patterson, 2017), given its potential to inform social policies and expand theoretical knowledge on whether and how particular family types interact with family processes in influencing child adjustment. Nonetheless, this study was the first to involve gay and heterosexual single father families formed through surrogacy—two small, but growing, family forms (Carone et al., 2017b; Eurostat, 2019) that raise concerns over whether the simultaneous presence of single parenthood, parents’ male gender (and non-heterosexual orientation, in the case of gay single fathers), and surrogacy conception is detrimental for child developmental outcomes (Lingiardi & Carone, 2016).

The lack of differences found in any of the outcome variables between family types (with the exception of parenting stress) supports the conclusion that child adjustment is more a function of parenting and relational processes within the family than family type. The findings enable practitioners to develop an informed view of the influence of assisted reproduction on the adjustment of children born to single fathers through surrogacy; they should also inform future decision making on regulation and the form such regulation should take in order to optimize family functioning and child adjustment in diverse family forms. In this vein, it is empirically unfounded for policymakers to consider children born to single fathers through surrogacy at risk of developing psychological problems, as well as to continue to ban single men from accessing fertility treatments.

Since children of single fathers were mean aged 5.5 years, several of them will begin elementary school in the next few years. From this point onward, these children will spend an increasing amount of time at school and in other peer contexts, and they will be more frequently confronted with views on their family and how it should be constructed. Amendments to the school syllabus that explain family diversity and human reproduction should inform children’s wider social environment about the existence of different family arrangements while preparing the children to cope with potential disapproval and stigmatization.

Although the findings of the present study do not confirm concerns about the detrimental effect of surrogacy and single fatherhood on child adjustment, it would be erroneous, however, to overlook or minimize the potential impact that such societal negative attitudes may have on children in these family forms, especially as they grow older and feel challenges associated with their family type and issues surrounding identity formation in relation to their conception method more acutely. In this vein, future research should address children’s conceptualizations of their single father family and their use of coping strategies to manage teasing experiences (should these occur) in order to better inform families, childcare providers, and schools about how to socialize these children around their family diversity, talk about issues such as discrimination and resilience, and support their learning to cope with adversity. Additionally, it will be important to follow up with these families over time to investigate whether “sleeper effects” are likely to operate at later developmental stages, such that the negative effects of surrogacy and single parenthood on children’s psychological adjustment, identity formation, and relationships with their fathers become apparent.

References

Abidin, R. (1990). Parenting stress index (PSI) – Test manual. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press.

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232.

Armesto, J. C. (2002). Developmental and contextual factors that influence gay fathers’ parental competence: A review of the literature. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 3, 67–78.

Aspland, H., & Gardner, F. (2003). Observational measures of parent-child interaction. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8, 136–144.

Baiocco, R., Carone, N., Ioverno, S., & Lingiardi, V. (2018). Same-sex and different-sex parent families in Italy: Is parents’ sexual orientation associated with child health outcomes and parental dimensions? Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 39, 555–563.

Biblarz, T. J., & Stacey, J. (2010). How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 3–22.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bos, H. M. W., & Gartrell, N. K. (2010). Adolescents of the USA National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Can family characteristics counteract the negative effects of stigmatization? Family Process, 49, 559–572.

Bos, H. M. W., & van Balen, F. (2008). Children in planned lesbian families: Stigmatization, psychological adjustment and protective factors. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 10, 221–236.

Bos, H. M. W., van Balen, F., van den Boom, D. C., & Sandfort, T. G. (2004). Minority stress, experience of parenthood and child adjustment in lesbian families. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 22, 291–304.

Cabrera, N., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bradley, R. H., Hofferth, S., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71, 127–136.

Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12, 152–157.

Carneiro, F. A., Tasker, F., Salinas-Quiroz, F., Leal, I., & Costa, P. A. (2017). Are the fathers alright? A systematic and critical review of studies on gay and bisexual fatherhood. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1636.

Carone, N., Baiocco, R., & Lingiardi, V. (2017a). Italian gay fathers’ experiences of transnational surrogacy and their relationship with the surrogate pre-and post-birth. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 34, 181–190.

Carone, N., Baiocco, R., & Lingiardi, V. (2017b). Single fathers by choice using surrogacy: Why men decide to have a child as a single parent. Human Reproduction, 32, 1871–1879.

Carone, N., Lingiardi, V., Chirumbolo, A., & Baiocco, R. (2018). Italian gay father families formed by surrogacy: Parenting, stigmatization, and children’s psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1904–1916.

Chan, R. W., Raboy, B., & Patterson, C. J. (1998). Psychosocial adjustment among children conceived via donor insemination by lesbian and heterosexual mothers. Child Development, 69, 443–457.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Coles, R. L. (2015). Single-father families: A review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7, 144–166.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting. The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55, 218–232.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267.

De Wert, G., Dondorp, W., Shenfield, F., Barri, P., Devroey, P., Diedrich, K., et al. (2014). ESHRE task force on ethics and law 23: Medically assisted reproduction in singles, lesbian and gay couples, and transsexual people. Human Reproduction, 29, 1859–1865.

Deakin, H., & Wakefield, K. (2014). Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14, 603–616.

Deater-Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 314–332.

Derogatis, L. R. (2001). Brief symptom inventory (BSI) 18: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson.

Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605.

Development Core Team, R. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org.

Dienes, Z. (2011). Bayesian versus orthodox statistics: Which side are you on? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 274–290.

Erez, C., & Shenkman, G. (2016). Gay dads are happier: Subjective well-being among gay and heterosexual fathers. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12, 451–467.

Eurostat (2019). People in the EU – statistics on household and family structures. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=People_in_the_EU_-_statistics_on_household_and_family_structures#Single-person_households.

Farr, R. H. (2017). Does parental sexual orientation matter? A longitudinal follow-up of adoptive families with school-age children. Developmental Psychology, 53, 252–264.

Farr, R. H., Bruun, S. T., & Patterson, C. J. (2019). Longitudinal associations between coparenting and child adjustment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parent families. Developmental Psychology, 55, 2547–2560.

Fedewa, A. L., Black, W. W., & Ahn, S. (2015). Children and adolescents with same-gender parents: A meta-analytic approach in assessing outcomes. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 11, 1–34.

Fletcher, R., StGeorge, J., & Freeman, E. (2013). Rough and tumble play quality: Theoretical foundations for a new measure of father–child interaction. Early Child Development and Care, 183, 746–759.

Gartrell, N. K., Bos, H. M. W., & Koh, A. (2018). National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study—Mental health of adult offspring. New England Journal of Medicine, 379, 297–299.

Goldberg, A. E., & Gartrell, N. K. (2014). LGB-parent families: The current state of the research and directions for the future. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 46, 57–88.

Golombok, S. (2015). Modern families: Parents and children in new family forms. Cambridge, UK: University Press.

Golombok, S., Blake, L., Slutsky, J., Raffanello, E., Roman, G. D., & Ehrhardt, A. (2018). Parenting and the adjustment of children born to gay fathers through surrogacy. Child Development, 89, 1223–1233.