Abstract

This paper is the result of a research that evaluated the levels of prejudice against sexual and gender minorities within 28 Brazilian public schools. The research considered a sample of 413 teachers, 97 employees, and 1829 students from 28 public high schools, located in four Brazilian states: Rio Grande do Sul, Minas Gerais, Ceará, and Pernambuco. All of them answered a questionnaire on sociodemographic data, the revised version of the Prejudice Against Sexual and Gender Diversity scale. The resulting analysis highlighted that religious individuals and followers of the Neo-Pentecostal church in the three study groups presented higher levels of prejudice than the other groups involved. All groups that have done previous training in the subject of prejudice presented inferior scores to those that had not done. Individuals that stated they have gay man, lesbian woman, travestis persons, or transsexual persons as friends, relatives, and acquaintances in the groups of teachers and students presented a lower level of prejudice compared to those who did not have relationships with people with these characteristics. Our results suggest the need for methodological changes in schools so that institutions can prepare their curriculum and their pedagogical practices considering the current multiple existing sexual and gender orientations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

LGBT Prejudice in Brazil

Brazil is the country with the highest number of murders motivated by homophobia and transphobia (Borges & Meyer, 2008). According to data from the Report for Homophobic Violence in Brazil (Secretaria de Direitos Humanos da Presidência da República, 2018), the Brazilian Federal Government registered 1876 crimes motivated by homophobia and transphobia in 2016.

A survey published in 2009 by the Ministry of Health of Brazil with 18,500 students, mothers, parents, directors, and teachers pointed out that more than 90% of the respondents demonstrated biased attitudes toward non-heterosexual individuals (Mazzon, 2009). Another study conducted by ABGLT (2016), with a sample of 1016 Brazilian students between 13 and 21 years old, indicated that school environment is perceived as threatening and violent for LGBT (lesbian woman, gay man, bisexual, and transgender person) teenagers. Seventy-three percent of LGBT students reported having suffered verbal violence as a result of their sexual orientation. This percentage was the worst among the countries participating in the survey, followed by Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. More than 25% of students reported avoiding wearing certain clothes (30.6%) and a fifth reported avoiding sports facilities or institutions of the educational institution (22.1%). In addition, 60.2% reported feeling insecure in the educational institution last year because of their sexual orientation while 42.8% reported feeling the same insecurity because of the way they expressed their gender.

Based on the research results herein analyzed, the initial hypothesis indicates that men have higher levels of prejudice against sexual and gender minorities than women. Also, the international studies appoint that certain religions have higher rates of prejudice than other religions. On average, heterosexual men express less comfort with sexual minorities and more negative attitudes toward sexual minorities than heterosexual women (Herek, 2002; Herek & Gonzalez-Rivera, 2006). In relation to religions, there are also an expressive number of studies that discuss the associations between sexual prejudice and religion (Herek, 1994; Whitley, 2009), showing that homosexuality and sexual minority individuals seem to evoke a bad representation to certain religions, even when compared to acts that are not accepted such as divorce (Herek & McLemore, 2013).

Empirical studies measuring prejudice against sexual and gender minorities in Brazilian schools are limited in both number and scope (Costa et al., 2015b; Costa & Nardi, 2015). Even though these surveys have repercussions in a context-dependent manner and analyzed in given place and social experience, they help to compose a framework on the subject in Brazil. Research about prejudice against sexual and gender minorities seems to be relevant in contributing to change Brazilian social reality in this field.

Defining Prejudice

Prejudice is a positive or negative attitude directed at a group of people, or directly at the people who are part of it, which creates or maintains a hierarchical status relationship (Dovidio, Hewstone, Glick, & Esses, 2010). It is formed according to stereotypes present in certain cultures in order to justify and maintain social inequalities. According to Herek (2016), prejudice is a social conception, which can be translated into a sexual stigma (relating to homosexual people, bisexual, or heterosexuals) or a gender stigma (relating to transsexual persons, transgender persons, and travestis persons), which manifests in different forms in aggressors and victims. Travesti is a Brazilian culturally specific transgender identity—designated male at birth, but who affirms female gender identity, in general, with no genital modification (Barbosa, 2013). Victims, apart from being subject to discrimination (felt stigma), also incorporate a negative model of themselves, manifested in negative attitudes that may be associated with negative mental health (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003).

Brazilian society is defined by heterosexism, cissexism, and genderism. Heterosexism is a belief system that defines heterosexuality more valuable than homosexuality/bisexuality. Cissexism is a social belief that discriminates those who do not identify themselves with the sex given at birth. Genderism is a cultural belief that disseminates negative judgments of everyone who do not conform to sociocultural expectations of gender (woman or man). Those expressions propose to establish rules for sexual orientation and gender identity—sexual attraction must be directed exclusively to the opposite sex and gender identity must necessarily be linearly constructed according to the sex designated at birth (Morin, 1977; Hill & Willoughby, 2005; Bilodeau, 2007; Jourian, 2015; Serano, 2016).

Brief Notes About Brazilian Educational History

Schools should ensure a space where young people can make their first social interactions beyond the gaze of their families, learning to compose unique perceptions about the world and themselves. They can transform society, helping to create an inclusive and safe space for learning (Borges & Meyer, 2008).

Currently, the 9th world economy (IMF, 2018), Brazil is a Latin American, Portuguese-speaking country, colonized by Portugal in the sixteenth century. The first public education institution was built in the city of Salvador in 1549, by Manuel da Nóbrega, a Portuguese Jesuit priest, head of the first Jesuit mission to the land. Right after their arrival, colonizers began imposing the European culture original people in the land: the children of families involved in the cultivation of sugar cane began to receive humanistic education (learning about art, painting, poetry, and literature in general), and the indigenous (native people) and African people, the latter trafficked from Africa as slaves, were forced to follow the Catholic faith (Cunha & Barbosa, 2015). Brazilian education remains marked by religious doctrine until now (de Almeida, 2014). An example of this is the 2017 Brazilian Supreme Court ruling reaffirming that public schools could have religious classes even though attendance is not mandatory.

Following the enactment of the 1988 Federal Constitution, a series of changes occurred in the education legal frame. Initially, sexuality was treated in biology classes with a purely biological approach (Quirino & Rocha, 2012). In the 1990s, schools’ main concern was with sexually transmitted disease prevention. The creation of the National Curricular Parameters (NCPs), which are guidelines developed by the Brazilian Federal Government to guide professors, school principals, and educators in general through the Brazilian educational system (promoting discussions, orientations, and educational recommendations), made possible for the topic of sexuality be approached in the initial years as a way of reducing the violence caused by prejudice (Palma, Piason, Manso, & Strey, 2015).

In addition to the NPCs, other post-Constitution rules should be cited: (i) National Education Guidelines and Bases Law (Law 9394/96), (ii) National Human Rights Program II, (iii) National Rights Education Plan Human Rights, (iv) National Plan of Policies for Women, and (v) Brazil Without Homophobia Program—guidelines and bases of national education with the aim of guaranteeing equality and respect for minorities, fairness, women’s autonomy, and social justice (Borges & Meyer, 2008). Other important programs launched in Brazil in recent years were Health and Prevention in Schools, developed jointly between the Ministry of Education and Health, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations Fund for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) all aiming to integrate health and education (approaching topics such as sexually transmitted infections and teenage pregnancies) among young students aged 10 to 24 years old (Mello, Freitas, Pedrosa, & Brito, 2012).

The “Brazil Without Homophobia” program, launched by the Federal Government in 2004, focused in combating violence and prejudice against sexual and gender minorities. In 2011, an agreement signed by the National Fund for the Development of Education (FNDE) prepared pedagogical material (“Educational Kit Against Homophobia”) that would be distributed to public education institutions throughout Brazil. UNESCO had expressed support for the project when it stated that it would contribute to the reduction of stigma and discrimination, as well as to the promotion of equality and quality education. However, conservative sectors of society with representation in the National Congress were able to block the distribution of these materials (Mello et al., 2012).

Religious conservatism in Brazil was also responsible for the non-validation of topics involving sexual and gender minorities in educational institutions in the last National Education Plan (PNE), which determines strategies and guidelines on Brazilian educational policy every decade. According to the Brazilian Basic Educational Guidelines Law, since 1996, the responsibility of schools should go beyond the classical curriculum. They must promote actions aimed at the citizenship of their students and support the promotion of democratic experiences through curricular policies for an education that is inclusive and potentially open to cultural diversity (Mello et al., 2012).

In practice, however, the curricular proposals and educational policies of schools usually end up reproducing social patterns derived from the disciplinary and normative logic, legitimizing power relations and hierarchy, silencing in situations of violence reported by LGBT students (Palma et al., 2015). Brazilian educational policies aligned with a normative culture, classify as out of the context those who do not consider themselves heterosexual, generate an often hostile and prejudiced environment (Unesco, 2015).

Research Goals

The main objective of the present study was to investigate prejudice toward gender and sexual minorities (GenSex prejudice) in Brazilian public high schools using a psychometrically valid instrument and representative sample. Although researches on this subject are frequent in the international scientific scenario, in Brazil, they are scarce. We were interested in identifying a broad range of variables that predict anti-LGBT prejudice. To achieve this goal, we worked with a relevant number of variables, such as sexual orientation, gender, and religiosity and the scientific literature points out that those variables are the most associated with prejudice against sexual and gender minorities (Herek & McLemore, 2013).

Method

Participants

A sample of 2784 people (485 teachers, 126 employees, and 2173 students) participated in the study. The average age of the participants was 22.69 (40.07 for teachers, 40.33 for employees, and 17.83 for students), ranging from 13 to 67 years old. Most participants declared themselves to be heterosexual (91.80%). A total of 30.90% of people identified themselves as male and 69.10% as female. The characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 1.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Variables and Psychosocial Characteristics

Participants answered questions related to sociodemographic information about the Brazilian state where the school was located, age, gender (female, male, or other), sexual orientation (heterosexual, non-heterosexual, or I do not know), place of residence (urban or rural), place of work/study (urban or rural), level of education, social class (approximate monthly family income) (A = R$ 9263/US$ 3000; B = R$ 5241/US$ 1600; C = R$ 1685/US$ 535; D/E = R$ 776/US$ 246 – Exchange Rate verified on 07/19/2017, according to the Brazilian Association of Research Companies - ABEP, 2011). Participants were asked if they had a religion. Those who answered affirmatively were asked about which religion they belonged to and their religious attendance. They were asked about access to information in their residence—measured by five questions related to the consumption of radio, newspapers, magazines, internet, and television if they had already participated in any training, class, or related course on gender identity, sexuality, and sexual diversity. Finally, they were asked if they had friends, relatives, and acquaintances who were gay man, lesbian woman, travestis persons, or transsexual persons. Those who answered affirmatively were asked about the degree of relationship with these people.

Prejudice Against Sexual and Gender Diversity

A questionnaire of 16 items investigated GenSex prejudice (Costa, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2015a), although there is also a revised version of this instrument (Costa, Machado, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2016). Participants were consulted about their attitudes (beliefs, feelings, and behaviors) toward gay man, lesbian woman, travesti, transgender person, and gender non-conforming people. Although assess gender and sexuality prejudice altogether, the scale is unidimensional. The processes of item selection were based in two systematic reviews (Costa, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2013a; Costa, Peroni, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2013b) and a panel of specialists. Validation was performed using item response theory and classical methods (exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and criterion validity). All analyses appointed to good evidence of validity and veracity. This scale is composed of items such as “homosexual men are perverts” and “travestis make me sick.” Participants responded to a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree completely). Cronbach’s alpha indicated high internal consistency (α = .93).

Procedures

This study was conducted in 28 public high schools, located in 4 states and 12 cities of Brazil: Porto Alegre, Venâncio Aires, and Santa Cruz do Sul (in the Rio Grande do Sul state); Belo Horizonte, Araçuaí, Contagem, Juiz de Fora, and Divinópolis (in the Minas Gerais state); Fortaleza, (in Ceará state); and Recife, Goiana and Vitória de Santo Antão (in Pernambuco state). In Brazil, the high school corresponds to basic education, consisting of a period of 3 years, directed to the students of the age group between 16 and 18 years old. It is equivalent to the period from 10th to 12th year in high school in the USA. Participating schools and cities were selected by convenience.

Data were collected between February 2013 and March 2014. The principals of the schools signed a letter of institutional agreement in order to authorize the conduction of the research. After receiving information about the purpose of the study, the participants were asked to answer the self-administered questionnaire. The terms of consent were obtained directly from the participants—those over 18 signed for themselves, and, in the case of minors, the signature of the responsible (s) gave authorization. The instruments were administered by trained researchers, individually in the case of teachers and employees, and in the group in the case of students. Participants who responded to less than 80% of the prejudice against sexual and gender diversity (PASGD) were excluded from analyses. Then, the missing cases were inputted by regression considering gender, age, and group membership (student, teacher, or employee). After removing the missing cases (445), 2339 people remained (413 teachers, 97 employees, and 1829 students).

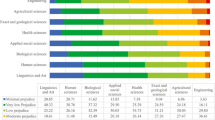

We also conducted a Pearson correlation between all metric and ordinal variables. Table 2 shows the correlation between all the metric and ordinal variables. The total score of the scale was computed by calculating the arithmetic average of the items. Student’s t tests were performed to establish the difference in the total score between gender groups (male or female), religiosity (yes or no), place of residence (urban or rural), workplace/school (urban or rural), level of access to information (high or low), LGBT friends (yes or no), and previous training in the subject (yes or no). ANOVA was used for those variables with more than two groups: level of education (fundamental incomplete, fundamental complete, high school incomplete, high school complete, undergraduate, postgraduate), social class (A, B, C, D, E), state (RS, MG, CE, PE), sexual orientation (heterosexual, non-heterosexual, I do not know), religion (Buddhism, Afro-Brazilian (Candomblé/Umbanda), Catholicism, Neo-Pentecostals, Spiritism, Protestantism, Judaism, Islam or other), and religious attendance (high attendance, low attendance, no attendance). Bonferroni comparisons were also used. All analyses considered teachers, employees, and students separately. The magnitude of the effect and a 95% confidence interval were calculated for all analyses. The analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package (21.0) (Tables 3, 4, and 5).

Ethical Procedures

This research was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul – UFRGS, under project number 04642712.9.0000.5334.

Results

General Prejudice—Teachers

ANOVAs and Student’s t test indicated that there was no significant difference in the scale of prejudice between the average of men and women, nor among social class, level of education, place of residence, and place of work.

There was a difference in relation to the state of residence (F(3,409) = 9.99, CI95% = 1.90, 2.10, p < .001, ηp2 = .07), with teachers from the Northeast presenting higher prejudice scores than teachers residing in other regions. Teachers residing in Ceará presented higher averages than those residing in Minas Gerais (p < .001) and the Rio Grande do Sul (p < .001). Teachers residing in Pernambuco presented higher averages in comparison to those residing in Minas Gerais (p = .002) and the Rio Grande do Sul (p = .002).

There was also a difference in relation to the level of information (t(23.201) = 3.308, 95% CI 2.27, 2.67, p = .003, d = 1.37), with teachers with high access to information presenting lower average scores (M = 2.00, DP = 0.93) than teachers with low access to information (M = 2.96, SD = 1.37). There was a significant difference in relation to being religious (t(101.884) = 5.11, 95% CI = 1.72, 1.97, p < .001, d = .62), in which professors who declared themselves as religious persons had a higher average (M = 2.36, SD = 1.03) than those who declared were not religious persons (M = 2.15, SD = 0.97).

A difference was observed in relation to the religion affiliation (F(8,337) = 12.49, CI95% = 1.77, 2.32, p < .001, ηp2 = .23). Neo-Pentecostals teachers had a higher average than catholic teachers (p < .001), spiritists (p < .001), Afro-Brazilian religions (candomblé/umbanda) (p < .001), and others (p = .002). Spiritist teachers had a lower average than protestants (p = .013) and catholics (p = .049). Muslims were not included in the post hoc analysis because there were fewer participants than two. Religion attendance led to a statistical significant difference (F(2,343) = 14.94, 95% CI = 1.93, 2.20, p < .001, ηp2 = .08): professors whom declared themselves as very religiously engaging had a higher average of prejudice (p < .001) than non-engaged professors (p < .001).

Student’s t test indicated a significant difference between previous training in the subject (t(95) = − 2.73, 95% CI = 2.02, 2.24, p = .008, d = .33), with non-trained teachers presenting higher averages (M = 2.31, SD = 1.15) than teachers who underwent training (M = 1.96, SD = 0.89). There was a significant difference in having LGBT friends (t(33.49) = − 4.68, 95% CI = 2.35, 2.68, p < .001, d = .98). Teachers who declared that did not have LGBT friends presented a higher average (M = 3.07, SD = 1.31) than teachers who reported having LGBT friends (M = 1.97, SD = 0.90).

Finally, there was a significant difference in relation to sexual orientation (F(2,410) = 2.21, 95% CI = 1.29, 2.76, p < .001, ηp2 = .32), with heterosexual teachers presenting a higher average of prejudice against gender and sexuality minorities (M = 2.09, SD = 0.97) than non-heterosexual teachers (M = 1.68, SD = 1.02).

General Prejudice—Employees

ANOVAs and Student’s t test indicated that there was no significant difference on the average between men and women, social class, a state in which the employees reside, place of residence, place of work, level of access to information, religious attendance, having LGBT friends, and sexual orientation.

However, in relation to educational level there was a difference (F(5,91) = 2.78, 95% CI = 2.02, 2.62, p = .019, ηp2 = .14), with postgraduate employees presenting a significantly lower average than employees who completed high school only (p = .015).

There was a significant difference in relation to having a religion (t(95) = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.75, 2.37, p = .013, d = .82). The ones who declared themselves as religious persons had a higher average (M = 2.45, SD = 1.02) than the ones who declared did not have one (M = 1.67, SD = .88). There was a difference in relation to which religion they were affiliated (F(4,80) = 3.49, 95% CI = 2.21, 2.92, p = .011, ηp2 = .15), with neo-pentecostals having an average higher than spiritists (p = .016).

Student’s t test indicated a significant difference between having previous training in the subject on the prejudice scale (t(95) = − 2.73, 95% CI = 2.20, 2.61, p = .008, d = .55). Employees who did not perform training presented higher average (M = 2.69, SD = 1.11) than employees who underwent training (M = 2.13, SD = 0.92).

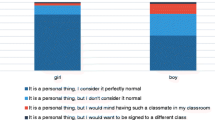

General Prejudice—Students

The only variable that did not present a significant difference was social class. Student’s t test indicated that there was a difference between students with respect to gender (t(1595.59) = 10.26, 95% CI = 2.33, 2.42, p < .001, d = .49), with male students presenting higher mean scores (M = 2.61, SD = 1.03) than female students (M = 2.14, SD = 0.92).

There was a difference in relation to sexual orientation on the prejudice scale (F(2,183) = 29.51, 95% CI = 1.30, 2.761, p < .001, ηp2 = .03). Those who defined themselves as non-heterosexuals had a lower average than heterosexual students (p < .001), as well as in relation to the ones who declared did not know their sexual orientation (p = .001).

There was a difference in relation to the level of information (t(1.82) = 2.80, 95% CI = 2.35, 2.48, p = .005, d = .13), in which students with low access to information had a higher average (M = 2.52, SD = 1.01) than students with high access to information (M = 2.32, SD = 0.99).

Similarly, the difference according to the location of the school was significant (t(1.83) = − 4.62, 95% CI = 2.47, 2.63, p < .001, d = .43). Students in rural schools (M = 2.74, SD = 1.01) presented a higher average than students studying in urban schools (M = 2.32, SD = 0.99).

There was a difference in relation to the state in which the student resided (F(3,1825) = 30.35, 95% CI = 2.36, 2.45, p < .001, ηp2 = .05). Students residing in Minas Gerais presented lower averages that students residing in the Rio Grande do Sul (p = .001), Ceará (p < .001), and Pernambuco (p < .001). Students residing in the Rio Grande do Sul had a lower average than students residing in Ceará (p < .001) and Pernambuco (p < .001).

There was a significant difference in relation of religion (t(652.49) = 8.36, 95% CI = 2.16, 2.27, p < .001, d = .31). Students who declared themselves as religious had higher averages (M = 2.44; SD = 1.00) than the non-religious ones (M = 2.00, SD = 0.89). A difference was observed in relation to the religion affiliations (F(7,1440) = 20.55, 95% CI = 2.07, 2.40), p < .001, ηp2 = .09). Neo-pentecostal students had a higher average than catholic (p < .001), spiritists (p < .001), Afro-Brazilian religions (candomblé/umbanda) (p < .001), buddhists (p = .02), and other (p = .001). Students of the spirit religion had a lower average than catholics (p < .001), protestants (p < .001), and other (p = .003) students. Religious attendance led to a significant difference (F(2,144) = 13.93, 95% CI = 2.36, 2.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .02). Students who declared high religious attendance had a higher average than students with low attendance (p < .001) or no attendance (p < .001).

Student’s t test indicated a significant difference between having previous training in the subject on the scale of prejudice among students (t(1,827) = − 2.48, 95% CI = 2.31, 2.41, p = .013, d = .12). Those who did not attend training presented higher average (M = 2.43, SD = 0.98) than students who underwent training (M = 2.30, SD = 1.00). There was a significant difference in having LGBT friends (t(1,827) = − 11,726, 95% CI = 2.53, 2.65, p < .001, d = .75). Students who declare that did not have LGBT friends presented higher average (M = 2.95, DP = 0.97) than students who reported having an LGBT friend (M = 2.23, SD = 0.96).

Discussion

The sample presented significant results in relation to GenSex prejudice in the three groups, reinforcing arguments that support the need for reformulation and implementation of anti-discrimination policies in the Brazilian educational system.

The analysis indicated that teachers and students living in the states of Ceará and Pernambuco had a higher degree of prejudice than the ones in the states of the South and Southeast. Regional differences in income and education may help to account for these findings. According to Atlas Brazil (2013), the municipal human development index in education, per capita income, and life expectancy of the population, in general, is higher in the states of the South and Southeast and lower in the states of the Northeast: MG (0.638, US $ 232, 75.30 years), RS (0.642, US $ 270, and 75.38 years), PE (0.574, US $ 163, and 72.32 years), and CE (0.615, US $ 143, and 72.60 years). Regions, where there is greater socioeconomic development, tend to have more public policies and campaigns, which could also explain the lower level of prejudice in these locations. The State of Rio Grande do Sul, for example, enacted Law No. 11,872 in 2002, which prohibits acts that threaten the dignity of the human person, especially in relation to freedom of orientation, practice, manifestation, identity, and sexual preference.

Students residing and studying in rural areas had a higher level of prejudice compared to the ones in urban areas. International studies point out that students living in urban areas can be more tolerant in having gay man and lesbian woman as classmates compared to the ones living in rural areas (Pitonak & Spilková, 2015).

Teachers, employees, and students who declared to be affiliated to one religion presented a higher degree of prejudice than those who reported being not affiliated. In relation to religious attendance, teachers and students who declared high attendance had a higher degree of prejudice than the ones with no or lower attendance. Students of the neo-pentecostal religion had a higher degree of prejudice than the other religions. Spiritist students showed less prejudice than the Catholics, protestants, or any other religion. A large number of religious doctrines, while repudiating certain kinds of prejudice, such as racial prejudice, are far less tolerant to GenSex minorities because they understand that gay man, lesbian woman, and transgender people challenge the value systems of their beliefs (Whitley, 2009). This is the case of the evangelical (Pentecostal and neo-pentecostal) religions that often understand homosexuality as a sin, psychic illness, and demonic act (Mesquita & Perucchi, 2016). Monotheistic religions, such as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, also tend to be more conservative, unlike Afro-Brazilian, spiritism, and Buddhist religions, which may have more tolerant attitudes. In Brazil, spiritism springs from the multiplicity of other doctrines, such as Catholicism and Afro-Brazilian religions, carrying a more plural religious tone (Camurça, 2009).

Although the variable educational level was not significant for the group of teachers, postgraduate employees showed a lower degree of prejudice than those who declared that they only had undergraduate or high school degrees. Several studies on GenSex prejudice have found the idea that higher levels of education are more common to be associated with lower levels of prejudice (Bartos, Berger, & Hegarty, 2014; Costa, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2015a).

Teachers, employees, and students who reported having participated in past GenSex discrimination training had less prejudice than the ones who reported had never participated. Studies have shown that educating people on certain topics through participation in workshops or courses helps to modify pre-established concepts, modifying negative attitudes toward minority groups and targets of discrimination (Riggs & Fell, 2010; Riggs, Rosenthal, & Smith-Bonahue, 2011; Burford, Lucassen, & Hamilton, 2017).

Teachers and students who stated that they had LGBT friends presented a lower degree of prejudice compared to the ones who answered negatively. Studies have shown that individuals who maintain relationships with people with sexual orientations and other genders than their own may present a lower degree of prejudice than those who do not maintain this kind of social and affective interaction (Cunningham & Melton, 2013; Unlu, Beduk, & Duyan, 2016). Some studies have also shown that keeping in touch with lesbian and gay man is more associated with lower degrees of prejudice in heterosexual people (Smith, Axelton, & Saucier, 2009).

Male students (identified at birth) presented a higher degree of prejudice than female students. There is already consensus in several studies that women tend to present few prejudice attitudes and beliefs against GenSex minorities (Mata, Ghavami, & Wittig, 2010; Pitonak & Spilková, 2015). Men may be socially more pressured to adopt a traditional view of gender (Davies, 2004). More negative attitudes toward the lesbian woman, gay man, and transgender person could be more related to a general adherence in men to traditional gender roles (Fisher et al., 2017). In addition, the male gender still occupies a space of greater access to rights in contemporary society, which is confirmed by research that demonstrates that being in a socially dominant position is more positively associated with prejudice against subjects of subordinate groups (Mata et al., 2010).

Educational Policy Implication

In recent years, Brazil is dealing with conservative values from part of society. This can be evidenced for example by the “Escola Sem Partido” (“School Without Parties”) a draft bill that aims to prevent schools from dealing with students on issues such as gender and sexual orientation. Since the October 2018 election, a significant number of federal congressmen from conservative political parties have been elected, which may result in approval of this kind of legislation.

More than ever, it is fundamental that educational networks need broadening their views and promoting the good of all, leveraging actions to challenge prejudices of origin, sex, color, age, and any other forms of discrimination, exactly as highlighted in article 3 of the Federal Constitution of Brazil of 1988. Thus, from our point of view, educational institutions must include in their conceptions of individuals all perspectives of GenSex orientation, so that LGBT students can feel part of society at all levels (Magnus & Lundin, 2016).

It is important that school undergoes through a deep reformulation on its basic principles, with the participation of educators (Mello et al., 2012). Experiences of good practice in other countries can also be applied in the Brazilian context. This is the case of Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs). GSAs are school groups, devised by students and teachers, which emerged in the state of Massachusetts in the early 1980s, with the goal of promoting respect among students regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. Since then, GSAs have been implemented throughout the USA to promote individual support, discuss and resolve GenSex conflicts, increase the visibility of the problems faced by LGBT students, and ensure that the school becomes a safe place for all that live there (Marx & Kettrey, 2016). The groups are operated by the youth themselves and have an adult counselor; together, they promote a space of mutual support and self-esteem building, placing the students in an agency position. Schools that rely on GSAs have presented lower rates of health and academics risks (Davis, Stafford, & Pullig, 2014; Poteat, Heck, Yoshikawa, & Calzo, 2016).

Limitations

There are several limitations to the present study. The main purpose of this article was to produce a descriptive analysis prioritizing univariate statistics, due to its correlational nature, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship between a variable and thus have certainty about the direction of the effects. We worked on this paper with indications based on our results and other researches. An experimental, longitudinal, and/or multivariate analysis should also be explored in future manuscripts. This study worked with a sample of only four Brazilian states. For future researches, it is suggested wider samples due to the territorial and cultural amplitude of Brazil. Also, future investigations should include legal guardians as the fourth group of participants, given family constitutes an important link in the search of the confrontation of prejudice.

Conclusions

This study presents the need to stimulate the regular training and awareness of populations to contribute to the reduction of stigma and discrimination in relation to individuals whose sexuality is not normative. It proposes to promote public policies to combat GenSex prejudice, with the aim to outline strategies for coping with this phenomenon. Schools need to receive concise orientation from government with mechanisms to implement in the education guidelines. This will depend on changes in many levels. The political parties representing the evangelical party in the Brazilian National Congress have been systematically opposing to proposed legislation focused on sexuality, allowing religious moral dogmas influencing the voting of such kind of legislation, causing Religion influencing State guidance (Souza, 2013), which challenges the provision of article 19, I, of the Brazilian Constitution that provides about the secularity of the Brazilian State.

The presence of professionals with critical training in gender and sexuality, whether in psychology or in other fields, could facilitate the management of the discussions for the implementation of such an agenda in the school context. This kind of professional could act as a mediator between school and family, helping understanding the urgency of combating GenSex prejudice. Public and private campaigns promoting the problematization of discrimination, its risks, and losses, also appear to be fundamental in the search for a more equal society.

The Ministry of Education has promoted publications on the subject of homophobia and school diversity in recent years, but it is fundamental the continuous production of materials about the topic; thus, the relationship between State and science does not dissolve (Mello et al., 2012). It is essential that this interaction follows a scientific and non-partisan approach as a State rather than a Government policy; otherwise, every exchange of government may jeopardize the visibility of the subject of prejudice. GenSex discrimination needs to be presented in numbers in order to such information is firmly inserted in the society, ending the false impression that such violence does not exist in Brazil.

References

Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa - ABEP. (2011). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Brazil’s Economic Classification Criteria]. Retrived 02 January 2017, from http://www.abep.org.

Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais (2016). Secretaria de Educação. Pesquisa Nacional sobre o Ambiente Educacional no Brasil 2015: As experiências de adolescentes e jovens lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis e transexuais em nossos ambientes educacionais. Retrived 20 October 2018, from http://static.congressoemfoco.uol.com.br/2016/08/IAE-Brasil-Web-3-1.pdf.

Atlas do Desenvolvimento Humano do Brasil. (2013). Retrived 02 January 2017, from http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/2013.

Barbosa, B. C. (2013). “Freaks and whores”: Uses of travesti and transsexual categories. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad, 14(2), 352–379.

Bartos, S. E., Berger, I., & Hegarty, P. (2014). Interventions to reduce sexual prejudice: A study-space analysis and meta-analytic review. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(4), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.871625.

Bilodeau, B. L. (2007). Genderism: Transgender students, binary systems and higher education. Germany: VDM Verlag.

Borges, Z. N., & Meyer, D. E. (2008). Limites e possibilidades de uma ação educativa na redução da vulnerabilidade à violência e à homofobia [Limits and possibilities of an educational action in the reduction of the vulnerability to violence and homophobia]. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 16(58), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-40362008000100005.

Brasil. Ministério da Educação, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais, & Fundação Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas. (2009). Pesquisa sobre discriminação e preconceito no ambiente escolar. Brasília: Ministério da Educação Retrived from 10 October2013,fromhttp://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/download/texto/me04651a.pdf.

Burford, J., Lucassen, M. F., & Hamilton, T. (2017). Evaluating a gender diversity workshop to promote positive learning environments. Journal of LGBT Youth, 14(2), 211–227.

Camurça, M. A. (2009). Entre sincretismos “guerras santas” dinâmicas e linhas de força do campo religioso brasileiro [Between sincretismos dynamic “holy wars” and lines of strength of the Brazilian religious field]. Revista USP, 81, 173–185. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9036.v0i81p173-185.

Costa, A. B., & Nardi, H. C. (2015). Homofobia e preconceito contra diversidade sexual: Debate conceitual. [Homophobia and prejudice against sexual diversity: Conceptual debate]. Temas em Psicologia, 23(3), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2015.3-15.

Costa, A. B., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2013a). Systematic review of instruments measuring homophobia and related constructs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(6), 1324–1332. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12140.

Costa, A. B., Peroni, R. O., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2013b). Homophobia or sexism? A systematic review of prejudice against nonheterosexual orientation in Brazil. International Journal of Psychology, 48(5), 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.729839.

Costa, A. B., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2015a). Avaliação do preconceito contra diversidade sexual e de gênero: construção de um instrumento [Evaluation of prejudice against sexual and gender diversity: Construction of an instrument]. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 32(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-166x2015000200002.

Costa, A. B., Peroni, R. O., de Camargo, E. S., Pasley, A., & Nardi, H. C. (2015b). Prejudice toward gender and sexual diversity in a Brazilian public university: Prevalence, awareness and the effects of education. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 12(4), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0191-z.

Costa, A. B., Machado, W. d. L., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2016). Validation study of the revised version of the scale of prejudice against sexual and gender diversity in Brazil. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(11), 1446–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1222829.

Cunha, C. F. B., & Barbosa, C. F. (2015). Estado laico: Conhecimento religioso democrático em escola pública contemporânea [Lay state: Democratic religious knowledge in contemporary public school]. Juiz de Fora, MG, Brasil: Anais do XIV Simpósio Nacional da ABHR Retrived from http://www.abhr.org.br/plura/ojs/index.php/anais/article/view/870. Accessed Aug 2018.

Cunningham, G. B., & Melton, E. N. (2013). The moderating effects of contact with lesbian and gay friends on the relationships among religious fundamentalism, sexism, and sexual prejudice. The Journal of Sex Research, 50, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.648029.

Davies, M. (2004). Correlates of negative attitudes toward gay men: Sexism, male role norms, and male sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552233.

Davis, B., Stafford, M. B. R., & Pullig, C. (2014). How gay-straight alliance groups mitigate the relationship between gay-bias victimization and adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(12), 1271–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.010.

de Almeida, J. S. (2014). Meninos e meninas estudando juntos: os debates sobre as classes mistas nas escolas brasileiras: (1890/1930) [Boys and girls learning together: The debates about mixed classes in brasilians schools: (1890/1930)]. Revista HISTEDBR On-line, 58, 115–123. Retrived from http://periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/histedbr/article/view/8640382

Dovidio, J. F., Hewstone, M., Glick, P., & Esses, V. M. (2010). Prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination: Theoretical and empirical overview. The SAGE handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination, 3–29.

Fisher, A. D., Castellini, G., Ristori, J., Casale, H., Giovanardi, G., Carone, N., ... & Ricca, V. (2017). Who has the worst attitudes toward sexual minorities? Comparison of transphobia and homophobia levels in gender dysphoric individuals, the general population and health care providers. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 40(3), 263–273.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730.

Herek, G. M. (1994). Assessing heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A review of empirical research with the ATLG scale.

Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66(1), 40–66.

Herek, G. M. (2016). A nuanced view of stigma for understanding and addressing sexual and gender minority health disparities. LGBT Health, 3(6), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0154.

Herek, G. M., & Gonzalez-Rivera, M. (2006). Attitudes toward homosexuality among US residents of Mexican descent. Journal of Sex Research, 43(2), 122–135.

Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. A. (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333.

Hill, D. B., & Willoughby, B. L. (2005). The development and validation of the genderism and transphobia scale. Sex Roles, 53(7/8), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7140-x.

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (2014). Censo Escolar 2014 [School census 2014]. Brasília, Brazil. Retrived 02 January 2017, From http://portal.inep.gov.br/censo-escolar.

Internacional Monetary Fund (2018). Retrived 20 December 2018, from www.imf.org

Jourian, T. J. (2015). Evolving nature of sexual orientation and gender identity. New Directions for Student Services, 2015(152), 11–23.

Magnus, C. D., & Lundin, M. (2016). Challenging norms: University students’ views on heteronormativity as a matter of diversity and inclusion in initial teacher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 79, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.06.006.

Marx, R. A., & Kettrey, H. H. (2016). Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0501-7.

Mata, J., Ghavami, N., & Wittig, M. A. (2010). Understanding gender differences in early adolescents’ sexual prejudice. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(1), 50–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609350925.

Mazzon, J. A. (2009). Projeto de estudo sobre ações discriminatórias no âmbito escolar, organizadas de acordo com áreas temáticas, a saber, étnico-racial, gênero, geracional, territorial, necessidades especiais, socioeconômica e orientação sexual. São Paulo: Fundação Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas.

Mello, L., Freitas, F., Pedrosa, C., & Brito, W. (2012). Para além de um kit anti-homofobia: Políticas públicas de educação para a população LGBT no Brasil [In addition to an anti-homophobia kit: Public education policies for the LGBT population in Brazil]. Bagoas, 7, 99–122 Retrived 02 January 2017, from https://periodicos.ufrn.br/bagoas/article/view/2238.

Mesquita, D. T., & Perucchi, J. (2016). Não apenas em nome de Deus: Discursos religiosos sobre homossexualidade [Not just in the name of god: Religious discourses on homosexuality]. Psicologia & Sociedade, 28(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-03102015v28n1p105.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Morin, S. F. (1977). Heterosexual bias in psychological research on lesbianism and male homosexuality. American Psychologist, 32(8), 629–637.

Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura [Unesco]. (2015). La violencia homofóbica y transfóbica en el ámbito escolar: hacia centros educativos inclusivos y seguros en América Latina. Paris: Unesco.

Palma, Y. A., Piason, A. D. S., Manso, A. G., & Strey, M. N. (2015). Parâmetros curriculares nacionais: Um estudo sobre orientação sexual, gênero e escola no Brasil. Temas em Psicologia, 23(3), 727–738. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2015.3-16.

Pitonak, M., & Spilková, J. (2015). Homophobic prejudice in Czech youth: A sociodemographic analysis of young people’s opinions on homosexuality. Sexual Research Policy, 13(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0215-8.

Poteat, V. P., Heck, N. C., Yoshikawa, H., & Calzo, J. P. (2016). Greater engagement among members of gay-straight alliances: Individual and structural contributors. American Educational Research Journal, 53(6), 1732–1758. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216674804.

Quirino, G. S., & Rocha, J. B. T. (2012). Sexualidade e educação sexual na percepção docente [Sexuality and sex education in teachers’ perception]. Educar em Revista, 43, 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40602012000100014.

Riggs, D. W., & Fell, G. R. (2010). Teaching cultural competency for working with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans clients. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 9(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2010.9.1.30.

Riggs, A. D., Rosenthal, A. R., & Smith-Bonahue, T. (2011). The impact of a combined cognitive–affective intervention on pre-service teachers’ attitudes, knowledge, and anticipated professional behaviors regarding homosexuality and gay and lesbian issues. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.002.

Secretaria de Direitos Humanos da Presidência da República. (2018). Relatório Sobre Violência Homofóbica no Brasil. Brasília: Author Retrived 18 November 2018, From http://www.mdh.gov.br/biblioteca/consultorias/lgbt/violencia-lgbtfobicas-no-brasil-dados-da-violencia.

Serano, J. (2016). Whipping girl: A transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. UK: Hachette.

Smith, S. J., Axelton, A. M., & Saucier, D. A. (2009). The effects of contact on sexual prejudice: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles, 61(3–4), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9627-3.

Souza, S. D. (2013). Política religiosa e religião política: os evangélicos e o uso político do sexo [Religious Politics and Religion Politics: Evangelicals and the Political Use of Sex]. Estudos de Religião, 27(1), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.15603/2176-1078/er.v27n1p177-201.

Transrespect versus Transphobia. (2016). Retrived 02 January 2017, from http://transrespect.org/en/about/tvt-project.

Unlu, H., Beduk, T., & Duyan, V. (2016). The attitudes of the undergraduate nursing students towards lesbian women and gay men. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3697–3706. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13347.

Whitley, B. E., Jr. (2009). Religiosity and attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A meta-analysis. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508610802471104.

Funding

This project was sponsored by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stucky, J.L., Dantas, B.M., Pocahy, F.A. et al. Prejudice Against Gender and Sexual Diversity in Brazilian Public High Schools. Sex Res Soc Policy 17, 429–441 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00406-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00406-z