Abstract

While it is clear that there are existing prejudices directed toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people across the globe, very few studies have provided in-depth investigations of such attitudes from an international comparative perspective, and no cross-cultural studies to date have investigated attitudes toward bisexual and transgender individuals. Without understanding how correlates of attitudes toward LGBT individuals are both similar and different across multiple international locations, it is unclear how we can learn to counteract negative prejudices toward these groups. In the current study, we explore how measures of politics, feminism, and religion affect attitudes toward LGBT individuals using Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales and data from four college student samples in Oklahoma, Texas, Italy, and Spain (N = 1311). Results suggest three trends: (1) negative attitudes toward LGBT individuals are more pervasive in Oklahoma than in any of the other university samples and are most positive among Spanish students; (2) negative attitudes toward LGBT individuals are related to the individual and multiplicative effects of political beliefs, feminism, and religiosity across all four samples; and (3) constructs related to attitudes toward gays/lesbians differ from those that relate to attitudes toward bisexual and transgender individuals. Such findings indicate that there are important similarities and differences in prejudices toward LGBT individuals and that attitudes toward bisexual and transgender individuals should be included in future international comparative research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals are a topic of interest across the globe (e.g., Bolton 1994; Hagland 1997; Smith et al. 2014); however, research examining cross-cultural differences in attitudes is limited. The existing data suggest some global trends toward greater support of lesbian and gay rights in some countries; however, such findings vary by world region (e.g., Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Lippincott et al. 2000), and much research relies exclusively on comparisons across European countries (e.g., Kuntz et al. 2015; Slenders et al. 2014; van den Akker et al. 2013). Furthermore, no studies to date have examined attitudes toward bisexual or transgender persons using cross-cultural data. This is especially significant because prejudices about bisexual and transgender individuals differ from those directed toward gays and lesbians (Worthen 2013), and while gay and lesbian rights have been at the forefront of many recent political debates, issues facing bisexual and transgender people remain largely on the outskirts of most political platforms.

Examining attitudes toward LGBT people and issues is especially important because attitudinal changes can lead to significant cultural shifts. Indeed, there may be an important relationship between public attitudes and changes in laws and public policy (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). For example, when same-sex marriage was legalized in Spain in 2005, this was the result of a culmination of a series of demands that the general public and left-wing politicians sought after (Platero-Méndez 2007), and a similar pattern of events led to same-sex marriage legalization in the USA in 2015 (Harrison 2015). Perhaps due to its profoundly Catholic cultural milieu, same-sex marriage continues to be a polarizing issue in Italy in 2016 (Povoledo 2016). Thus, there may be an important relationship between public support of LGBT issues and changes in laws that affect LGBT individuals (Fingerhut et al. 2011; Hull 2006; Inglehart and Welzel 2005).

However, laws comprise only one form of social regulation, while social attitudes and prejudices can sometimes control and regulate sexual behavior more so than criminal law and policy (Frank et al. 2010). For example, the hesitance of both right-wing politics and mainstream Christian belief systems to embrace the rights of LGBT individuals restricts both laws and informal social control systems effecting LGBT people’s lives. Thus, LGBT prejudices can affect laws and policy on a global scale. In the current study, we examine how measures of politics, feminism, and religion affect attitudes toward LGBT individuals using Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales and data from the USA (Oklahoma and Texas), Italy, and Spain with the larger goal of developing a more in-depth understanding of global LGBT prejudices.

Existing Research and the Importance of Cross-Cultural Attitudes Toward LGBT People

In general, existing cross-cultural public opinion surveys in this area of inquiry have investigated simplistic measures of tolerance of “homosexuals” and “gay” rights (Gallup World Poll, Eurobarometer, European Social Survey, International Social Survey Program, Latinobarometer, Pew Research Center Global Attitudes Survey, World Values Survey, see Smith et al. 2014). Trends suggest that there has been an increasingly positive attitudinal shift when it comes to gay/lesbian rights in many parts of Europe as well as in the USA (Smith et al. 2014). Across the three countries of interest in the current study, the USA is least tolerant, followed by Italy, with Spain reporting significantly higher levels of tolerance toward “homosexual” behavior (Smith et al. 2014). Such international public opinion surveys are effective at providing cross-cultural samples that can be compared easily; however, their measures are typically limited. In general, these surveys ask questions about “homosexuality” or “same-sex behavior” but do not inquire about attitudes toward bisexual or transgender individuals specifically nor do they consistently include diverse measures that may allow us to better understand attitudes toward LGBT individuals using multiple dimensions. Thus, we have little information regarding cross-cultural US and European prejudices about bisexual and transgender individuals and the diverse belief systems associated with attitudes toward LGBT people.

This is significant because often the dominant discourse in political, legal, and criminal realms is about gay and lesbian rights. As a result, much of what we know is relatively specialized to issues effecting gay and lesbian people. This is highly problematic because as Bauer et al. (2009) suggest, transgender people currently represent one of the most marginalized groups in the USA. Indeed, recent research with 6450 transgender and gender non-conforming study participants determined that a staggering 41 % reported attempting suicide (compared to 1.6 % of the general population) and 90 % reported experiencing harassment, mistreatment, or discrimination in the workplace (Grant et al. 2011). In a global survey of over 2500 respondents, 90 % of Italian transgender people indicated experiencing harassment in public places (Turner et al. 2009) and nearly one third (28 %) of the 71 murders of transgender people in Europe from 2008 to 2013 occurred in Italy (the second-highest rate in Europe after Turkey) (Prunas et al. 2015). Bisexual people and issues remain virtually invisible and are largely buried in the rubric of “LGBT” issues, which mainly focus on lesbian and gay rights in both the USA and Europe despite the fact that bisexual prejudices remain especially prominent (Worthen 2012) and that the risk of suicide is higher for bisexual people as compared to gay and lesbian people (Brennan et al. 2010; Steele et al. 2009). Thus, it is essential to call attention to bisexual and transgender prejudices when examining the belief systems associated with attitudes toward LGBT people.

Political, Feminist, and Religious Belief Systems and Attitudes Toward LGBT Individuals

Currently, the political and religious climates in the USA, Italy, and Spain are filled with debate about LGBT rights. Many of these perspectives about “LGBT issues” are actually built from and within larger belief systems. A belief system can be defined as a “configuration of ideas and attitudes in which the elements are bound together by some form of constraint or functional interdependence” (Converse 1964, p. 206). Such belief systems can function as heuristic devices that individuals use to organize their opinions and attitudes about important issues. For example, researchers have found that most people utilize “information shortcuts” when making political decisions (Brody and Lawless 2003, p. 54; see also Popkin 1994). Indeed, political parties themselves are organized in such a way to allow voters to be able to use these information shortcuts to choose the political candidate they would like to support. Some even suggest that “voters need to know only what liberals and conservatives generally support” in order to choose who they will vote for in the next election (Brody and Lawless 2003, p. 55).

Political Beliefs

General measures of political beliefs are often employed by researchers to understand attitudes toward specific topics. Within the USA, political beliefs are usually measured on a simple spectrum (typically a Likert-type index from liberal to conservative) with those identifying as more liberal usually being more supportive of the rights of LGBT individuals. Studies utilizing such measures in the USA indicate a strong relationship between self-reported conservative political ideology and negative attitudes toward homosexuals (Tygart 1999), bisexuals (Mohr and Rochlen 1999), and transgender people (Norton and Herek 2013). Similarly, studies of political attitudes among Europeans also utilize simplistic Likert-type indices and show that those with “right-wing” (conservative) views tend to have more negative attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men than those with “left-wing” (liberal) views (Calvo 2008; Pichardo-Galán et al. 2007; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights FRA 2009; European Commission 2008; Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015). Although the operationalization of political beliefs as “conservative” to “liberal” and right-wing to left-wing may seem rather unsophisticated, interestingly, studies indicate that most people organize their political leanings in these simplistic ways. For example, American social psychological research shows that students overwhelmingly support policies if they align with their preferred party (Republican or Democrat). They need not even know the particulars of such policies, instead they blindly support them because they have the seal of approval from their preferred party candidate who embodies either a conservative or liberal political ideology (Cohen 2003). Indeed, there is an established trend in previous studies that finds that these simplistic measures of political beliefs are significantly related to LGBT prejudices (e.g., Mohr and Rochlen 1999; Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015; Norton and Herek 2013).

While such previous studies show a link between political beliefs and attitudes toward LGBT individuals, it is important to understand why this relationship exists. D’Emilio’s (2002) work shows that the role of gays and lesbians in marriage, the military, parenting, media/arts, hate crimes, politics, public school curricula, and religion became a part of predominant political and social discourse in the 1990s, “Gay issues in this period became a permanent part of the world of politics and public policy, and gay people became a regularly visible part of American cultural and social life” (p. 91). Similarly, the political contexts of Italy and Spain have been painted with debates about LGBT rights in recent decades; many of which continue today (Baraldi 2008; Cartabia et al. 2010; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights FRA 2011; Povoledo 2016). We suggest that “liberal vs. conservative” may be currently organized as “pro-LGBT rights vs. anti-LGBT rights.” Indeed, political candidates may actually classify their platforms based on their stance toward LGBT issues (Lewis 2005). At their core, the foundational components of political conservatism include “avoidance of uncertainty and an intolerance of ambiguity as well as resistance to change and justification of inequality” (Norton and Herek 2013, p. 741; see also Jost et al. 2003). Thus, politically conservative people are less likely to support LGBT people because they challenge core aspects imbued within conservative paradigms. Furthermore, the relationship between political beliefs and attitudes toward LGBT individuals may be especially salient due to the current heated political debates about LGBT rights in both the USA and Europe.

Feminist Identity

Another important belief system that may be related to attitudes toward LGBT individuals is feminism. Millett (1970) suggests that the structured relationships of power that exist between the sexes create a system of dominance in which men control women. Contemporary scholars would agree that “feminism” is based on this idea that this system is flawed and there should be equality between the sexes (e.g., Morgan 1996). While a great deal of work has identified the multifaceted perspectives of feminism (e.g., Collins 2000), the choice to identify as “feminist” has always been controversial. Williams and Wittig (1997) report that while many support the goals and feminist values of the women’s movement, few are willing to identify as “feminists.” Those who do identify as feminists are more likely to support the goal of equality between the sexes and liberal sex role ideologies (Williams and Wittig 1997). Some studies have also shown that support of a basic tenet of feminism, “equality between men and women,” has been found to be related to more positive attitudes toward gays and lesbians (Ojerholm and Rothblum 1999), bisexuals (Mayfield and Carrubba 1996), and transgender individuals (Hill and Willoughby 2005; see also Norton and Herek 2013).

Connell (1990) further contextualizes sexual politics in the realm of the slogan “the personal is political.” Connell (1990) purports that this relationship between the personal and the political is a basic feature of both feminist and gay/lesbian politics and a link between personal experience and power relations (see also Taylor and Rupp 1993). Generally speaking, fights for LGBT rights and feminism represent challenges to traditional definitions of sex roles and efforts to combat prejudices (Worthen 2012, 2016). Research indicates that self-identified feminists are more likely than non-feminists to report supportive attitudes toward gays and lesbians (Minnigerode 1976; Ojerholm and Rothblum 1999) and are less likely to focus on the need to maintain traditional sex role divisions (MacDonald et al. 1973). In addition, using Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales, Worthen (2012, 2016) found that self-identifying as a feminist is strongly related to supportive attitudes toward gay men, lesbian women, bisexual men and women, and trans individuals. While the relationships between feminism and attitudes toward LGBT individuals have been explored in US studies, we did not locate similar research in Italy and Spain. Thus, the current study is the first that has examined how feminist identity may affect attitudes toward LGBT individuals among Italians and Spaniards.

Religiosity

Religiosity is often explored as a correlate of attitudes toward LGBT individuals. Studies in the USA and Europe show that negative attitudes toward LGBT individuals are correlated with higher levels of religiosity (Herek 2002; Hinrichs and Rosenberg 2002; Larsen et al. 1980; Mohr and Rochlen 1999; Nagoshi et al. 2008; Tygart 1999; Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015; Pichardo-Galán et al. 2007; Sotelo 2000; Kelly 2001; van de Meerendonk and Scheepers 2004; Worthen 2012, 2014). Indeed, using Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales, Worthen (2012, 2016) found that religiousness, biblical literalism, and frequent church attendance are all strongly related to LGBT prejudices. However, it is important to examine the relationship between religiosity and prejudicial attitudes within cultural context. US researcher Allport (1966) states, “It is a well-established fact in social science that, on the average, churchgoers…harbor more…prejudice than do non-churchgoers” (p. 447). While it has been 50 years since this work on the religious context of prejudice was published, the origins of this relationship may still have meaning. For example, it is true that almost every religious group has (at least at one point in time) been a target of hostility. Thus, religious groups in both the USA and Europe have historical investments in group loyalty that can sometimes lead to distancing from outsiders (Adamczyk and Pitt 2009). This “distancing” may also be related to higher levels of prejudice directed toward outsiders. While we certainly see increasing diversity and acceptance in contemporary churches and religions, there is little doubt that societal prejudices directed toward particular groups are built from two pillars, one from religious doctrine and another from “clichés of secular prejudice” (Allport 1966, p. 450).

Furthermore, researchers suggest that religious belief systems have strong effects on social and political attitudes (DiMaggio et al. 1996; Green et al. 1996; Jaspers et al. 2007; Manza and Brooks 1997). Indeed, Boswell (1980) writes “hostility to gay people provides singularly revealing examples of the confusion of religious beliefs with popular prejudice…as long as the religious beliefs which support a particular prejudice are generally held by a population, it is virtually impossible to separate the two” (p. 5). Furthermore, church leaders may shape church attendees’ attitudes toward particular topics (Wald et al. 1988; Welch et al. 1993). For example, in studies of college students, researchers found that those identifying with a fundamentalist protestant religion and those who attend church more often report less supportive attitudes toward gays and lesbians (Hinrichs and Rosenberg 2002; Larsen et al. 1980; Worthen 2012, 2014). Alignment with fundamentalist protestant religions and Catholicism may be related to unsupportive LGBT attitudes because, generally, such religions utilize teachings from the Old Testament that have been described as condemnatory of homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender lives (although some interpret such biblical passages quite differently) (Boswell 1980; Tygart 1999). Furthermore, biblical literalists are typically strong supporters of “traditional” (i.e., cisgenderFootnote 1 man + woman) family values leaving little space for gay/lesbian, bisexual, and transgender relationships and families (Burdette et al. 2005; McDaniel and Ellison 2008). Thus, interpreting the bible “literally” may be significantly related to unsupportive LGBT attitudes (McDaniel and Ellison 2008; Worthen 2012). Church attendance may also amplify such negative LGBT attitudes since more involvement in church may represent more intense involvement with religion, which may also be related to higher levels of emersion within biblical literalism (Van de Meerendonk and Scheepers 2004). For example, Lubbers et al. (2009) found that religious practices (i.e., church attendance) were more strongly related to attitudes toward homosexuality than religious denonimation (see also Jost et al. 2003). Furthermore, those who attend church more often may also distance themselves from LGBT individuals. Indeed, research shows that higher levels of church attendance are related to social distancing from lesbians and bisexuals (Hinrichs and Rosenberg 2002) and negative attitudes toward LGBT individuals (Worthen 2012, 2014).

Relationships Among Political, Feminist, and Religious Belief Systems

There is clear evidence to support the individual ways that political, feminist, and religious belief systems relate to attitudes toward LGBT individuals; however, it is also important to recognize the relationships among these belief systems. Indeed, research indicates that there may be important interrelationships between attitudes toward sociopolitically motivated topics (such as LGBT rights) and religion, feminism, and political conservatism. For example, Brody and Lawless (2003) found that self-designated liberals were more likely than self-designated conservatives to support equality for women in social, economic, and political institutions and were also less likely to attend church. In the USA, the Republican (conservative) Party has defined itself as “anti-feminist” and anti-feminist groups (many of which are religious in nature) have rallied to combat laws and policies directed toward feminist goals (Young and Cross 2003, p. 207). Indeed, studies show that those who identify with feminism are less likely to have politically conservative beliefs compared to non-feminists (Cowan et al. 1992; Jackson et al. 1996; Liss et al., 2001; Roy et al. 2007. Thus, feminism may be a strong component of a liberal political ideology, and both may be related to attitudes toward LGBT individuals (Worthen 2012).

Furthermore, biblical literalists have aligned themselves with the Republican (conservative) Party (Layman 2001; McDaniel and Ellison 2008); thus, there may be an important relationship between conservative political ideology, biblical literalism, and attitudes toward LGBT individuals. Moreover, a recent cross-national study showed that attitudes about homosexuality are shaped by both religious beliefs and cultural contexts in both the USA and Europe (Adamczyk and Pitt 2009), and both religion and attitudes toward gender egalitarianism have been found to impact the degrees of public acceptance of homosexuality (Beckers 2010) and support of transgender people (Norton and Herek 2013). Finally, LGBT rights movements in the USA, Italy, and Spain certainly contribute to the politicization of attitudes toward LGBT individuals with liberal and left-wing political belief systems more likely to incorporate LGBT rights (Cartabia et al. 2010; Sanjuán et al. 2008). Since belief systems exhibit “remarkable durability and resilience” (Inglehart and Baker 2000; p. 49), it is important to examine how they affect prejudicial attitudes.

Furthermore, the interactive quality of belief systems and attitudes suggests the need for understanding the interrelationships between multiple beliefs systems (i.e., political, feminist, and religious) and the ways they may affect attitudes toward LGBT individuals. For example, overarching conservative perspectives may represent a general aversion toward anyone or anything that is perceived as a challenge to existing social and traditional values (Norton and Herek 2013). In this respect, negative attitudes toward LGBT people are collectively underscored by negativity toward outgroups, a perspective that has been historically linked to conservativism in both political and religious realms. In these ways, political, feminist, and religious belief systems are intimately and interactively tied to LGBT prejudices.

Current Study

In the current study, we offer comparisons of LGBT attitudes using data from the USA, Italy, and Spain (N = 1311). We expect that measures of political, feminist, and religious belief systems will operate in similar ways across all four samples but will vary in their intensity. As Lingiardi et al. (2005) suggest, the same trends regarding homophobia that American researchers usually find are reflected in Italian samples because the Catholic Church’s position regarding homosexuality as “intrinsically disordered” is arguably using religious and social conservatism in Italy in much the same way that both the Evangelical movement and the Catholic Church do in America. We expect to find similar processes at work in Spain as well. In doing so, we promote a global dialogue that speaks to a deeper understanding of how correlates of attitudes toward LGBT individuals are both similar and different across multiple international studies so that we can learn how to counteract negative prejudices toward these groups.

Methods

Locations of Research

We focused on the following four locations: Oklahoma (N = 829), Texas (N = 162), Italy (N = 218), and Spain (N = 102). For the US samples, we chose southern states since studies have shown that those in the south hold more negative attitudes toward homosexuals (Loftus 2001), bisexuals (Herek 2002), and transgender people (Norton and Herek 2013) compared to those living in other regions of the USA. We specifically chose Italy because it is one of the only countries in western Europe that does not currently recognize same-sex marriages (as of 2016) and there is limited existing research on homonegativity in Italy (see Lingiardi et al. 2015). For contrast, we chose Spain as a location for this research because Spain legally permits same-sex marriages but also experiences similar influences from the Catholic Church (Platero-Méndez 2007). Below, the cultures of these four locations are briefly described.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is located in the “bible belt” of the USA, which is a geographical region populated by large groups of fundamentalist Christians (Heyrman 1998). The bible belt is not only characterized by a strong religious culture, but it is also much more likely to be populated by “red states” (states that are dominated by republican votes in elections).Footnote 2 As far as rights for LGBT individuals, states in the bible belt are generally less supportive than states in other parts of the country. For example, Oklahoma does not prohibit employment discrimination based on sexual orientation (lgbtmap.org 2016). Although same-sex marriages are recognized, overall, Oklahoma is not only unsupportive of LGBT rights, but also, there is a strong concentration of political conservatism and religious fundamentalism; both of which negatively impact LGBT people’s lives in Oklahoma.

Texas

Texas is also located in the southern USA; however unlike Oklahoma, the large Mexican-American population of Texas makes Catholicism a very real part of the religious context of Texas (Bremer 2004). Texas is also a “republican state” but is not as “red” as Oklahoma. In addition, Texas has several “liberal pockets”; in the 2012 presidential election, 26 counties (10 %) in Texas supported Democratic candidate Obama. We chose to focus on a university located in a city in Texas that is often thought of as a “liberal pocket” within the highly conservative state. Even so, the statewide laws affecting LGBT individuals are very similar to those in Oklahoma. Thus, the similarities and differences between Oklahoma and Texas allow for an interesting juxtaposition of attitudes in the conservative bible belt (Oklahoma) and attitudes in a liberal pocket (Texas).

Italy

Italy’s heavily religious culture and political context is characterized by a growing social conservatism and negation of LGBT rights. The indifference of the state and the clear interference of the Vatican into “public affairs” justify and reinforce the invisibility of LGBT people and, indirectly, the discrimination and violence against LGBT individuals (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights FRA 2010). The only notable exception is legislative decree 216/2003, which includes sexual orientation as a protected characteristic in employment discrimination. Currently in 2016, Italy does not permit same-sex marriages; however, Italy was one of the first European countries to decriminalize same-sex sexual behavior. Even so, Rifelli (1998) describes strong prescriptions of “normal” sexuality that are evident within Italian culture. These include a dominant conservative, religious norm that sexuality should only occur between people of the opposite sex (cisgender, married, monogamous, and who have procreative intentions). Furthermore, LGBT identities violate the convictions, values, and moral customs about masculinity and femininity that are pervasive in Italian Catholic society (Capozzi and Lingiardi 2003).

Spain

The cultural context of Spain has been heavily influenced by the Catholic Church. During Franco’s fascist dictatorship, gays and lesbians were persecuted and the Catholic Church, traditionally very influential on Spanish society, heavily opposed LGBT rights (Arnalte 2003). Currently, although Catholicism is still pervasive, many Spaniards do not share the Church’s strict positions on LGBT issues (Calvo and Montero 2005) and Spain has seen some recent radical changes in support of LGBT rights. Indeed, from 2004 (when Zapatero was elected as Prime Minister), major legislative reforms took place, implementing not only the EU Directives on equal treatment but also granting same-sex marriages (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights FRA 2010). When a hate crime (based on sexual orientation) is committed, this is considered an aggravating circumstance and the penal code also prohibits the denial of public services/benefits for reasons of sexual orientation (Sanjuán et al. 2008). According to European Commission (2008), less than 35 % of Spaniards maintain a conservative (i.e., anti-LGBT rights) political position. Thus, Spain may be an important setting for understanding attitudes toward LGBT individuals in a country that both grants and protects LGBT rights but still experiences the influence of the Catholic Church.

Overall, the locations for this project allow for important international comparisons of LGBT attitudes as they vary by cultural landscape. As Inglehart and Welzel (2005) note, “a society’s cultural heritage is remarkably enduring” (p. 46), and since society’s culture shapes the values and behaviors of its people, it is important to examine how LGBT attitudes differ cross culturally. For example, although these locations are all industrialized, they are not “uniform” in culture (Inglehart and Welzel 2005, p. 47). Indeed, while the USA is often seen as world leader among industrialized nations, it is not the leader in cultural change, rather it is against the norm since it has much more traditional and religious values than other rich industrialized societies (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). While it is certainly true that the USA is (generally) much more conservative than some European nations, we go beyond “USA vs. Europe” and allow for a more nuanced investigation of a specific liberal pocket as compared to bible belt location within the USA while also offering explorations of attitudes in Spain and Italy (a country that has been historically excluded from studies about homonegativity; Lingiardi et al. 2015) to better understand LGBT prejudices.

Data

The data for this project were derived from anonymous paper/pencil surveys completed by undergraduate students who were recruited in classroomsFootnote 3 at large public universities located in urban areas.Footnote 4 For the US samples, students were recruited from 39 sociology classesFootnote 5 at two universities located in Oklahoma and Texas. The Italian and SpanishFootnote 6 samples were composed of university studentsFootnote 7 in a variety of majors.Footnote 8 All respondents with missing data were eliminated from analyses.

Dependent Variables

To measure attitudes toward LGBT individuals, we used Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales that are based on items from scales created by Raja and Stokes (1998), Mohr and Rochlen (1999), and Hill and Willoughby (2005). Using the items listed in Appendix A, Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales were initially developed through PCF analyses and optimized through orthogonal varimax rotation (retaining eigenvalues over one), which yielded five separate scales (see Worthen 2012 for more details about the construction of these scales; see e.g., Lin et al. 2016; Worthen 2012, 2014, 2016 for studies utilizing these scales). After investigating potential differences in attitudes toward lesbians and gays and attitudes toward bisexual men and women based on theoretical arguments outlined by Worthen (2013), these constructs were combined into the following two scales: attitudes toward gays/lesbians and attitudes toward bisexuals due to lack of significant differences in original constructs. The third scale, attitudes toward trans individuals, remained intact as described by Worthen (2012). Higher numbers represent higher levels of support for LGBT individuals.

Independent Variables

Conservative Political Beliefs

Respondents were asked to identify as (1) extremely liberal, (2) liberal, (3) moderate, (4) conservative, or (5) extremely conservative. Higher scores represent higher levels of political conservatism.

Non-Feminist Beliefs

Respondents were asked “Do you think of yourself as a feminist?” Response options were (1) yes, a strong feminist; (2) yes, a feminist; (3) no, I am not a feminist; and (4) no, I disagree with feminism. Higher scores represent greater alignment with non-feminist beliefs.

Religious Beliefs/Behavior

First, respondents were asked, “How often do you attend church?” Response options were (1) never, (2) a few times a year, (3) about once a month, (4) several times a month, and (5) every week. Second, respondents were also asked to describe how they felt about the bible. Those responding that they believed that “The bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word” were coded as (1) for Biblical Literalism while others were coded as (0).

Sociodemographics

There is evidence that sociodemographic factors contribute to attitudinal differences. Indeed, men have been found to hold significantly more negative attitudes toward LGBT individuals when compared to women in both US and European research (COGAM 1997; D’Augelli and Rose 1990; Eliason 1997; Hill and Willoughby 2005; Hinrichs and Rosenberg 2002; Larsen et al. 1980; Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015; Norton and Herek 2013; Pichardo-Galán et al. 2007; Worthen 2012, 2014, 2016). Furthermore, many have found that younger age is related to more positive attitudes toward homosexuals (Inglehart and Welzel 2005; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights FRA 2009; European Commission 2008), bisexuals (Eliason 1997), and transgender individuals (Landen and Innala 2000). Sexual orientation has also been found to be a correlate of attitudes toward LGBT people with LGBT people being more likely to support LGBT rights (Worthen 2016), and graduating from a large high school has also been shown to be related to more positive attitudes toward LGBT people (Worthen 2012).

Method of Analysis

First, means were compared by location using t tests in Table 1. Second, OLS regressions explored how measures of political beliefs, feminism, and religion affect attitudes toward LGBT individuals. Three separate sets of models predicting attitudes toward the three groups of individuals were estimated for all four samples. We conducted the STATA “powerreg” analysis and determined that the sample sizes are large enough to yield significant results (Cohen 1988). In Table 2, political beliefs, feminist beliefs, and religious beliefs/behavior, and controls are estimated as they relate to attitudes toward LGBT individuals. Table 3 includes the addition of interaction effects that were created using mean-centered variables. To adjust for skewness, a natural logarithmic transformation of each dependent variable was conducted (Cohen et al. 2003). A variance inflation factor (VIF) check was run following each regression to check for multicollinearity, and the mean VIF is reported at the bottom of Tables 2 and 3. Chatterjee et al. (2000) suggest that multicollinearity may exist when the largest VIF is greater than 10 or the mean of the VIF is considerably larger than 1. Using these criteria, none of our regressions presented problems with multicollinearity.

Results

t Test Results

Overall, attitudes toward LGBT individuals were mostly positive for all four locations; however, t tests results in Table 1 indicated several statistically significant differences (reported in superscripts next to mean values). For all attitudinal scales, the four samples were significantly different from one another with Oklahomans reporting the lowest level of support, followed by Texans and Italians, with Spaniards reporting the highest level of support. Oklahomans reported significantly higher levels of conservative political beliefs and biblical literalism compared to the other three locations; however, there were no significant differences in feminist identification levels across the four locations. In addition, Americans reported significantly higher levels of church attendance when compared to Europeans. Overall, the general pattern suggests that US samples have higher levels of conservative beliefs and religiosity when compared to the European samples, with Oklahomans reporting the highest and Spaniards reporting the lowest.

Regression Results

Attitudes Toward Gays and Lesbians: Column 1, Table 2

For Oklahomans and Italians, political beliefs, non-feminist identification, church attendance, and biblical literalism are all significantly related to attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Among Texans, there is a similar pattern; however, non-feminist identification is not significant. In contrast, among Spaniards, the only measure that is significantly related to attitudes toward gays and lesbians is political beliefs. Among the controls, being female is a consistent positive predictor of supportive attitudes toward gays and lesbians, while other controls offer little consistency. The R 2 values range from .26 (Spain) to .58 (Texas).

Attitudes Toward Bisexuals: Column 2, Table 2

Similar to the results from column 1, for Oklahomans, all four measures are significantly related to attitudes toward bisexuals; however, only two measures are significant for the other three samples. Among Texans and Italians, political beliefs and church attendance are significantly related to attitudes toward bisexuals and among Spaniards, the significant correlates are political beliefs and biblical literalism. Among the controls, being female is consistently related to supportive attitudes toward bisexuals in the US samples but not in the European samples. The R 2 values range from .25 (Italy) to .44 (Texas).

Attitudes Toward Transgender Individuals: Column 3, Table 2

For Oklahomans, all four measures continue to be significantly related to attitudes toward transgender people. For Texans, the following two measures are significant: political beliefs and biblical literalism. While two measures of are significant for Italians (political beliefs and non-feminist identification), there is only one measure that is significant for Spaniards, political beliefs. Among the controls, being female is related to supportive attitudes toward transgender individuals for three samples (Oklahoma, Texas, and Italy). The R 2 values range from .26 (Spain) to .45 (Texas).

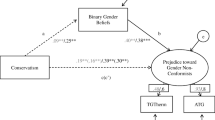

Regression Results with Interaction Effects: Table 3

Focusing on the interaction effects, we see that only a few are significant. The interaction of political beliefs and non-feminist identity is significantly related to attitudes toward gays and lesbians (Italy and Spain) and bisexuals (Oklahoma and Spain). This suggests that those with conservative political beliefs who also disagree with feminism are less likely to be supportive of gays and lesbians and bisexuals (in some locations). The only other significant interaction effect was the interaction of political beliefs and biblical literalism. This was significantly negatively related to attitudes toward bisexuals (Spain) and transgender individuals (Texas), suggesting that those with conservative political beliefs who are also biblical literalists are less likely to be supportive of bisexuals and transgender individuals. The individual effects of the belief system measures remain largely unchanged from Tables 2 and 3. As in Table 2, being female is relatively consistently related to supportive attitudes. The R 2 values range from .26 (Italy, attitudes toward bisexuals) to .60 (Texas, attitudes toward gays/lesbians).

Discussion

Overall, scholars suggest that the sexual culture of human beings is strongly affected by societal influences (Abramson and Pinkerton 1995; Terry 1999). Indeed, what it means to be “gay” or “transgender” in one society may differ from another. For example, Greenberg (1995) posits that cultures attach sexual meanings to certain behaviors and experiences, but not all cultures do so in the same ways (see also Koltko-Rivera 2004). As a result, social structures can facilitate or discourage certain sexual activities and gender identities, and this, in turn, can also affect attitudes toward sexual behaviors and identities (Greenberg 1995). These social structures can be informal (e.g., social interactions between individuals) and formal (e.g., formal messages from the church).

The current study shows that measures of politics, feminism, and religiosity are significantly related to attitudes toward LGBT individuals. Among all of the measures, the most consistent was political beliefs. For all models across all samples, more conservative political alignment was negatively related to supportive LGBT attitudes, and this is not surprising given the robustness of the relationship between political conservatism and LGBT prejudices found in previous research (e.g., Norton and Herek 2013; Lingiardi et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2014). Biblical literalism produced significant results for each location; however, the results were not as consistent as the effects of conservative political beliefs. Viewing the bible as “the word of god” may actually result in quite a bit of variance in attitudes. For example, some biblical literalists may view god as “wrathful,” while others might view god as “all loving” and such different perceptions affect prejudices in varying ways (Froese et al. 2008). Church attendance was also found to be significantly associated with LGBT prejudices in all locations except Spain (in which church attendance is comparatively lower than in the other three locations; Mazurczak 2014) but was also not as robust as political beliefs. This finding is consistent with past research that shows that church attendance is not as strongly related to prejudices toward outgroups when compared to biblical literalism (Froese et al. 2008). Among the interaction effects, only those that that included political beliefs were significant. Thus, measures of political conservativism may operate as a more consistent “information shortcut” for understanding attitudes toward LGBT issues when compared to church attendance and biblical literalism. In other words, while religious values, attitudes, and behaviors may entwine with perspectives about LGBT issues in various ways, being politically “conservative” is more strongly related to LGBT prejudices, and this is adequately captured in the current study with simplistic measures of self-reported political conservatism as seen in previous work (e.g., Norton and Herek 2013; Lingiardi et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2014).

The least consistent belief measure was non-feminist identification. Although being a non-feminist was strongly and significantly related to LGBT prejudices in Oklahoma as found in other US studies (Worthen 2012, 2016), surprisingly Italy was the only other location where the individual measure of non-feminist self-identification produced significant results. Feminist issues may entwine with LGT attitudes in Italy in unique ways because these issues have been historically linked. Indeed, in the 1990s, the intersections between feminist and lesbian politics coalesced into a women-only branch of Arcigay (Italy’s first and largest national gay organization) known as Arcilesbica, and thus, there is a very real overlap between feminist and lesbian movements in Italy (Malagreca 2006). And while lesbian activism also has an historical relationship within feminist movements in Spain as well including within the Grupo de Lesbianas, a lesbian feminist subgroup of COGAM (an LGBT rights organization based in Madrid) (Calvo and Trujillo 2011), findings from the current study show that Italian LGT prejudices more closely align with anti-feminism. However, among Spanish respondents, the interaction effect between political beliefs and non-feminist identification is also significantly related to lesbian/gay and bisexual prejudices. Thus, results indicate that both feminist identity and political conservativeness play a role in LGBT attitudes. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the current study asked students to self-identify as feminist or not which most likely parceled out the “most non-feminist” from the “most feminist” students. Thus, the significant relationships between non-feminist identity and LGBT attitudes in the current study are likely underestimates, and future research with more nuanced measures of feminism could bolster the findings presented here.

Beyond emphasizing the significance of politics, feminism, and religiosity in LGBT attitudes, it is also important to underscore the importance of examining bisexual and transgender prejudices. As noted earlier, much of what we already know is relatively specialized to issues effecting gay and lesbian people due to the dominant discourse that often neglects issues specific to bisexual and transgender people despite the fact that many studies illustrate the high levels of harassment, violence, and risk of suicide evident in transgender and bisexual populations (Bauer et al. 2009; Brennan et al. 2010; Grant et al. 2011; Prunas et al. 2015; Turner et al. 2009). Furthermore, bisexual and transgender people and issues remain largely obscured and politically neglected. Thus, in the current study, we have called attention to global bisexual and transgender prejudices to better understand the belief systems associated with attitudes toward LGBT people and this has been fruitful. In particular, there are different correlates of attitudes toward gay/lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people, and these also vary cross culturally. For example, gay/lesbian prejudices are largely entwined with both political and religious beliefs/behaviors, while transgender prejudices in Spain appear to be mostly related to political beliefs.

Results from the current study suggest that there may be both similar and different roots and/or reinforcing mechanisms behind gay/lesbian, bisexual, and transgender prejudices that vary by culture. For example, research using a Chinese adaptation of Worthen’s (2012) Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales finds that measures of filial piety (parental respect, honor, and obedience) relate to Chinese college student attitudes toward gays/lesbians (Lin et al. 2016), and additional research also finds that disapproval of homosexuality in Confucian societies (Japan, South Korea, China, Taiwan, and Vietnam) is greater than in non-Confucian countries (Adamczyk and Cheng 2015). Other work comparing American and Dutch attitudes toward gays and lesbians finds that Americans are likely to justify their attitudes using beliefs related to social norms and religious opposition, while the Dutch are more likely to justify their attitudes using beliefs related to individual rights (Collier et al. 2015). Thus, the complexity behind motivations and justifications for LGBT prejudices may manifest differently from culture to culture but may also have some overarching similarities.

Overall, these results suggest that alignment with conservative political beliefs is a robust cross-cultural correlate of attitudes toward LGBT people. Such results are not surprising since past studies in both the USA and in Europe indicate that more conservative political beliefs are related to anti-LGBT attitudes (e.g., Calvo 2008; Norton and Herek 2013; Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015; Pichardo-Galán et al. 2007; Tygart 1999). Furthermore, the following two interaction effects involving conservative political beliefs were significant: the interaction effect of conservative political beliefs and non-feminist identity and the interaction effect of conservative political beliefs and biblical literalism. These findings suggest that these belief systems may amplify or “interact” with one another in ways that influence attitudes toward LGBT individuals. These ideologies may be inherently related to an underlying theme, the preference for a “traditional” family arrangement that includes a cisgender male husband and female wife who are in a marriage recognized by the church and state. Indeed, politically conservative groups, non-feminists, and biblical literalists would all agree that this traditional family arrangement is preferred (Bendroth 1999; Brody and Lawless 2003; Young and Cross 2003). Furthermore, this preference for such a traditional family arrangement obfuscates and delegitimizes LGBT families. Thus, the conservative, non-feminist, and biblical literalist belief systems may “feed” off one another and may simultaneously influence negative attitudes toward LGBT individuals, as found in the current study. They may also be part of an overarching conservative value system or encompassing “worldview” that privileges power by rejecting members of outgroups (Koltko-Rivera 2004, p. 3; Kuntz et al. 2015; Norton and Herek 2013). Indeed, worldviews that simultaneously privilege power and promote prejudice and inequality may encompass such conservative value systems which can be reinforced in social, political, and religious realms that are culturally variant (Koltko-Rivera 2004).

Such belief systems are not easily changed; indeed, they are embedded within individual and sociocultural history and the cultural significance of belief systems cannot be overlooked. While past research underscores the significance of the interplay between religious, societal norms, and cultural context (Boswell 1980; D’Emilio 2002; Terry 1999), it is especially important to understand how these belief systems affect LGBT prejudices. Since the current political landscapes of both the USA and Europe are ripe with debate about LGBT individuals and their rights, the current study has cultural significance. For example, since college students who report conservative, non-feminist, and biblical literalist beliefs are likely to have less supportive LGBT attitudes, it is essential that colleges utilize curricula that expose students to diverse ideologies so that we may be able to promulgate supportive LGBT attitudes. Indeed, college students may be the “face of the future” in that their ideas may represent signs of change in both the political and social realms of society. In the realm of LGBT rights, it is especially important to understand college student attitudes toward these issues so that we can contribute to movement toward inclusivity and the promotion of LGBT rights across the globe. Furthermore, since studies show a relationship between pervasive public prejudices, criminal laws, and public policy (Frank et al. 2010), changes in LGBT prejudices may also be reflective of movement toward changes in laws that affect LGBT individuals (Fingerhut et al. 2011; Hull 2006). Thus, if we can begin to understand LGBT prejudices at the collegiate level, we may be able to contribute to changes in college students’ LGBT prejudices. Such shifts may also affect changes in general public attitudes toward LGBT individuals which may, in turn, contribute to improvements in policy and laws that affect LGBT individuals.

While the findings of the current study are informative, there are some limitations worth noting. First, small non-random cross-cultural college samples may be biased in the following ways: (1) they may be unrepresentative of both the college population and the larger population in general, (2) they may represent a more liberal-leaning segment of society due to the well-documented relationship between education and liberal attitudes toward LGBT individuals (e.g., Astin 1998; Brake 2010; Norton and Herek 2013), and (3) they may misrepresent “college” populations since those who attend college in the USA may differ from those who attend college in Europe. Although efforts were made to choose comparable university samples, it is likely that the complexities within college populations may make the conclusions of this research speculative. Even though there are international public opinion surveys that make cross-cultural comparisons easier (i.e., World Values Survey 2005), their limited measures led us to collect our own data; however, we understand that this makes it especially difficult to provide robust cross-cultural comparisons. Even so, we feel that the results from the current study offer important contributions to the literature (discussed below). Second, even though STATA powerreg analyses determined that the sample sizes are large enough to yield significant results (Cohen 1988), the small sample sizes are a potential limitation to the current study. Third, our measures of politics, religion, and feminism are all based on simplistic indices, and although there is an established trend in previous research that finds that these types of measures yield significant relationships with LGBT prejudices (e.g., Mohr and Rochlen 1999; Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015; Norton and Herek 2013; Worthen 2012, 2016), future studies would benefit from more sophisticated measurement of these complex constructs. Related, these measures may have very different cultural significance and meanings. Although efforts were made to ensure the integrity of the translation of the survey from English (as originally created by the first author) to Italian and Spanish (as done by the second and third authors and a Spanish colleague), any conclusions drawn from the relationships between LGBT attitudes and these belief systems should be culturally sensitive and deserve further investigation. Finally, we did not have measures of race, ethnicity, class, or social desirability; thus, it would be most beneficial to include such variables in future work.

International comparative research can be especially informative; thus, future studies could expand upon the current study in several ways. First, the predictors explored in this project do not offer explanations for the psychological foundations of individual attitudes. Future studies might investigate individuals’ psychological backgrounds to best understand how anti-LGBT attitudes develop and flourish (see Lingiardi et al. 2015). Second, past studies conducted in the USA (e.g., Eliason 1997; Herek 2002), in Italy (Lingiardi et al. 2005, 2015), and Spain (Acuña-Ruiz and Vargas 2006; Pichardo-Galán et al. 2007) indicate that who know LGBT people have more supportive LGBT attitudes (i.e., Allport’s (1954) contact hypothesis). Thus, future studies might incorporate measures of LGBT affiliation and attitudes toward LGBT persons using an international comparative lens (for an exploration of this type, see Worthen, Lingiardi, and Caristo (under review)). Third, some research shows that income inequality, economic distress, and membership in the “working class” are negatively related to tolerance of gays and lesbians (Andersen and Fetner 2008; Inglehart and Baker 2000; Svallfors 2006; Slenders et al. 2014). Thus, future studies might examine how these factors may be related to more complex measures of LGBT attitudes. Finally, it would be most informative if more nationally representative international comparative research was conducted with non-college based samples so that LGBT prejudices could be better understood, especially in the realm of attitudes toward bisexual and transgender people.

Overall, the current study provides three important contributions to the literature. First, this is the only study to date that has examined attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals using an international comparative framework. Second, this study shows that among multiple measures of political, feminist, and religious belief systems, alignment with conservative political beliefs is the most consistent predictive measure of attitudes toward LGBT individuals across all four locations. Furthermore, the interactive effects of conservative political beliefs, feminism, and biblical literalism also influenced attitudes toward LGBT individuals. Thus, there may be important nuances in measures of conservative politics and interrelationships between belief systems that are especially informative when examining LGBT prejudices. Third, by examining LGBT prejudices as separate constructs, this study shows that attitudes toward gay/lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people may have different correlates that also vary cross culturally. Such findings demonstrate the importance of future international comparative studies examining LGBT attitudes so that US and European initiatives can be designed to counteract negative prejudices.

Notes

Cisgender is a label for individuals who have a match between the sex they were assigned at birth, their bodies, and their

personal gender identity (Worthen 2013).

For example, in the 2012 US presidential elections, all 77 counties in Oklahoma supported Republican candidate Romney; thus, Oklahoma is sometimes described as “the reddest state in the USA” (npr.com 2008).

Students were asked to take the survey and they told that if they did not want to complete the survey, they could sit quietly and read while others were completing the survey. The instructor was asked to leave the room while students completed the survey in order to reduce any potential biasing effects that might result from the presence of the instructor.

It is important to note that the structures of the US and European university systems do differ in ways that may affect the study body composition. For example, most European universities are “public” institutions, in which fees to attend are relatively low (most universities charge an enrollment fee between 500 and 1500€), while US universities require tuition payments that are much higher (ranging from $5000/year to more than $30,000 per year) (Sheng 2012). Thus, there may be some differences in socioeconomic status between the US and European samples.

US respondents were recruited from sociology classes, but only 26 % were sociology majors. Even so, it is important to note that some US research has shown that those with academic majors in humanities and liberal arts, especially those in majors that have classes about gender and sexuality (such as sociology), have been found to be more supportive of gay men and lesbian women when compared to students majoring in business and hard sciences (Bierly 1985; Larsen, Reed, and Hoffman 1980).

The survey was originally created by the first author, who is American, in English and the second and third authors, who are both Italian, translated the survey into Italian. The Spanish version was translated by a mother tongue Spanish psychologist who collaborated on the administration of the survey in Spain.

The majority of students in Spain were recruited from Madrid, while in Italy, most students were from Rome. Students were recruited from several universities, for Spain, Complutense, Università Autonoma, Alicante, Rey Juan Carlos, Carlos Tercero, and Santiago de Compostela, and for Italy, University of Milan, University of Turin, University of Rome, University of Siena, and University of Ancona. To test for differences by university, we ran each model with dummy variables to control for potential university effects. Results show that there were not significant differences by particular university in Spain or Italy, supporting the grouping of “Italian” and “Spanish” students.

The most common major among the European respondents was psychology (39 %) followed by liberal arts (19 %), law (11 %), engineering (9 %), medicine (7 %), and business (5 %).

References

Abramson, P., & Pinkerton, S. (1995). Sexual nature, sexual culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Acuña-Ruiz, A., & Vargas, R. (2006). Diferencias enlos prejuicios frente ala homosexualidad masculina en tres rangos deedad en una muestra de hombres y mujeres heterosexuals. Psicología desde el caribe. Universidad del Norte, 18, 58–88.

Adamczyk, A., & Cheng, Y. (2015). Explaining attitudes about homosexuality in Confucian and non-Confucian nations: is there a ‘cultural’ influence? Social Science Research, 51, 276–289.

Adamczyk, A., & Pitt, C. (2009). Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: the role of religion and cultural context. Social Science Research, 38, 338–351.

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. MA: Addison-Wesley.

Allport, G. (1966). The religious context of prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 5, 447–457.

Andersen, R., & Fetner, T. (2008). Economic inequality and intolerance: attitudes toward homosexuality in 35 democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 4, 942–958.

Arnalte, A. (2003). Retada de violetas. La represión delos homosexuales durante el Franquismo. La esfera delos libros España.

Astin, A. (1998). The changing American college student: thirty-year trends, 1966–1996. The Review of Higher Education, 21(2), 115–135.

Baraldi, M. (2008). Family vs solidarity: recent epiphanies of the Italian reductionist anomaly in the debate on de facto couples. Utrecht Law Review, 4(2), 175–193.

Bauer, G., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, M., & Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: how erasure impacts health care for transgender people. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20, 348–361.

Beckers, T. (2010). Islam and the acceptance of homosexuality: the shortage of socioeconomic well-being and responsive democracy, pp. 57–98 in Habib (ed.) Islam and Homosexuality. CA: Greenwood.

Bendroth, M. (1999). Fundamentalism and the family: gender, culture, and the American pro-family movement. Journal of Women’s History, 10(4), 35–54.

Bierly, M. (1985). Prejudice toward contemporary outgroups as a generalized attitude. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 15(2), 189–199.

Bolton, R. (1994). Sex science and social responsibility: cross-cultural research on same-sex eroticism and sexual intolerance. Cross-Cultural Research, 28, 134–190.

Boswell, J. (1980). Christianity, social tolerance and homosexuality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Brake, R. (2010). The shaping of the American mind. Intercollegiate Studies Institute American Civic Literacy Program. Available at http://chronicle.com/items/biz/pdf/2010%20Civic%20Lit%20Report%2012%2015%20FINAL_small_2_0.pdf

Bremer, T. (2004). Blessed with tourists: the borderlands of religion and tourism in San Antonio. U of North Carolina Press.

Brennan, D. J., Ross, L. E., Dobinson, C., Veldhuizen, S., & Steele, L. S. (2010). Men’s sexual orientation and health in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101(3), 255–258.

Brody, R. & Lawless, J. (2003). Political ideology in the United States: conservatism and liberalism in the 1980s and 1990. pp. 53–80 in Conservative Parties and Right-Wing Politics in North America. Schultze, Sturm, Eberle (eds.). Leske + Budrich: Opalden.

Burdette, A., Ellison, C., & Hill, T. (2005). Conservative Protestantism and tolerance toward homosexuals: an examination of potential mechanisms. Sociological Inquiry, 75, 177–196.

Calvo, K. (2008). The situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation in Spain. Sociological Country Report for FRA.

Calvo, K. & Montero, J. (2005). Valores Y Religiosidad. Pp. 147–170 in Torcal Pérez-Nievas and Morales (eds) España: Sociedad Y Política En Perspectiva Comparada. Tirant Lo Blanch: Valencia.

Calvo, K., & Trujillo, G. (2011). Fighting for love rights: claims and strategies of the LGBT movement in Spain. Sexualities, 14(5), 562–579.

Capozzi, P., & Lingiardi, V. (2003). Happy Italy?The Mediterranean experience of homosexuality psychoanalysis and mental health professions. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 5(1), 29–57.

Cartabia, M.; Crivelli, E.; Lamarque, E.; & Tega, D. (2010). Legal study on homophobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity. Available at: http://www.fra.europa.eu/fraWebsite/attachments/LGBT-2010_thematic-study_IT.pdf

Chatterjee, S., Hadi, A., & Price, B. (2000). Regression analysis by example. NY: John Wiley & Sons.

COGAM. (1997). Investigación sobre las Actitudes hacia la Homosexualidad enla Población Adolescente Escolarizada dela Comunidad de Madrid. Available at: http://www.cogam.org/_cogam/archivos/1437_es_Investigaci%C3%B3n%20sobre%20las%20actitudes%20hacia%20la%20homosexualidad.PDF

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cohen, G. (2003). Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 808–822.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Collier, K., Horn, S., Bos, H., & Sandfort, T. (2015). Attitudes toward lesbians and gays among American and Dutch adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(2), 140–150.

Collins, P. (2000). Black feminist thought. Boston: Routledge.

Connell, R. (1990). The state, gender, and sexual politics: theory and appraisal. Theory and Society, 19(5), 507–544.

Converse, P. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In Ideology and Discontent, Apter (ed.), pp. 206–61. NY: Free Press.

Cowan, G., Mestlin, M., & Masek, J. (1992). Predictors of feminist self-labeling. Sex Roles, 27(7/8), 321–330.

D’Emilio, J. (2002). The world turned. Durham: Duke University Press.

D’Augelli, A., & Rose, M. (1990). Homophobia in a university community: attitudes and experiences of heterosexual freshman. Journal of College Student Development, 31, 484–491.

DiMaggio, P., Evans, J., & Bryson, B. (1996). Have Americans’ social attitudes become more polarized? American Journal of Sociology, 102, 690–755.

Eliason, M. (1997). The prevalence and nature of biphobia in heterosexual undergraduate students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(3), 317–326.

European Commission (2008). Special eurobarometer 296. Discrimination in the European Union, chapter 9. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_296_en.pdf

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2009). Homophobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in the EU member states. Available at: http://www.fra.europa.eu/fraWebsite/attachments/FRA_hdgso_report_part2_en.pdf

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2010). Homophobia transphobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity. Available at: http://www.fra.europa.eu/fraWebsite/attachments/FRA-LGBT-report-update2010.pdf

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2011). Homophobia, transphobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in the EU member states. Available at: http://fra.europa.eu/fraWebsite/attachments/FRA-homophobia-synthesis-report-2011_EN.pdf

Fingerhut, A., Riggle, E., & Rostosky, S. (2011). Same-sex marriage: the social and psychological implications of policy and debates. Journal of Social Issues, 67(2), 225–241.

Frank, D., Camp, B., & Boutcher, S. (2010). Worldwide trends in the criminal regulation of sex, 1945 to 2005. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 867–893.

Froese, P., Bader, C., & Smith, B. (2008). Political tolerance and god’s wrath in the United States. Sociology of Religion, 69(1), 29–44.

Grant, J., Mottet, L., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: a report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Green, J., Guth, J., Smidt, C., & Kellstedt, L. (1996). Religion and the culture wars. Rowman Littlefield.

Greenberg, D. (1995). The pleasures of homosexuality, pp. 223–256 in Abramson, Pinkerton (eds.) Sexual Nature, Sexual Culture. Chicago: UC Press.

Hagland, P. (1997). International theory and LGBT politics testing the limits of a human rights-based strategy. GLQ, 3, 357–384.

Harrison, J. (2015). At long last marriage. American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law 24(1).

Herek, G. (2002). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. The Journal of Sex Research, 39(4), 264–274.

Heyrman, C. (1998). Southern cross. U of North Carolina Press.

Hill, D., & Willoughby, B. (2005). The development and validation of the genderism and transphobia scale. Sex Roles, 53(7/8), 531–544.

Hinrichs, D., & Rosenberg, P. (2002). Attitudes toward gay lesbian and bisexual persons among heterosexual liberal arts college students. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(1), 61–84.

Hull, K. (2006). Same-sex marriage. Cambridge Press

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65, 19–51.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy. NY: Cambridge Press.

Jackson, L., Fleury, R., & Lewandowski, D. (1996). Feminism: definitions, support, and correlates of support among female and male college students. Sex Roles, 34(9/10), 687–693.

Jaspers, E., Lubbers, M., & De Graaf, N. (2007). Horrors of Holland: explaining attitude change toward euthanasia and homosexuals in the Netherlands. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 19(4), 451–473.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Kelly, J. (2001). Attitudes towards homosexuality in 29 nations. Australian Social Monitor, 4(1), 15–22.

Koltko-Rivera, M. (2004). The psychology of worldviews. Review of General Psychology, 8(1), 3–58.

Kuntz, A., Davidov, E., Schwartz, S., & Schmidt, P. (2015). Human values, legal regulation, and approval of homosexuality in Europe: a cross-country comparison. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 120–134.

Landen, M., & Innala, S. (2000). Attitudes toward transsexualism in a Swedish national survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29, 375–388.

Larsen, K., Reed, M., & Hoffman, S. (1980). Attitudes of heterosexuals toward homosexuality: a Likert-type scale and construct validity. The Journal of Sex Research, 16(3), 245–257.

Layman, G. (2001). The great divide. NY: Columbia Press.

Lewis, G. (2005). Same-sex marriage and the 2004 presidential election. Political Science and Politics, 38(2), 195–199.

Lgbtmap.org. (2016). State policy profile—Oklahoma. Available at: http://lgbtmap.org/equality_maps/profile_state/37

Lin, K., Button, D., Su, M., & Chen, S. (2016). Chinese college students’ attitudes toward homosexuality: exploring the effects of traditional culture and modernizing factors. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(2), 158–172.

Lingiardi, V., Falanga, S., & D’Augelli, A. (2005). The evaluation of homophobia in an Italian sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34(1), 81–93.

Lingiardi, V., Nardelli, N., Ioverno, S., Falanga, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Tanzilli, A., & Baiocco, R. (2015). Homonegativity in Italy: cultural issues, personality characteristics, and demographic correlates with negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(2), 95–108.

Lippincott, J., Wlazelek, B., & Schumacher, L. (2000). Comparison: attitudes toward homosexuality of international and American college students. Psychological Reports, 87, 1053–1056.

Liss, M., O’Connor, C., Morosky, E., & Crawford, M. (2001). What makes a feminist? Predictors and correlates of feminist social identity in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 124–133.

Loftus, J. (2001). America’s liberalization in attitudes toward homosexuality 1973 to 1998. American Sociological Review, 66(5), 762–782.

Lubbers, M., Jaspers, E., & UIltee, W. (2009). Primary and secondary socialization impacts on support for same-sex marriage after legalization in the Netherlands. Journal of Family Issues, 30(12), 1714–1745.

MacDonald, A., Huggins, J., Young, S., & Swanson, R. (1973). Attitudes toward homosexuality: preservation of sex morality or the double standard? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40, 161.

Malagreca, M. (2006). Lottiamo ancora: reviewing one hundred and fifty years of Italian feminism. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 7(4), 69–89.

Manza, J., & Brooks, C. (1997). The religious factor in U.S. presidential elections, 1960–1992. American Journal of Sociology, 103, 38–81.

Mayfield, W. & Carrubba, M. (1996). Validation of the attitudes toward bisexuality inventory. 104th American Psychological Association Convention, Toronto.

Mazurczak, F. (2014, June 11). Is Spain regaining its faith? First Things Retrieved from: http://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2014/06/is-spain-regaining-its-faith

McDaniel, E., & Ellison, C. (2008). God’s party? Race, religion, and partisanship over time. Political Research Quarterly, 61, 180–191.

Millett, K. (1970). Sexual politics. NY: Doubleday Press.

Minnigerode, F. (1976). Attitudes toward homosexuality: feminist attitudes and sexual conservatism. Sex Roles, 2(4), 347–352.

Mohr, J., & Rochlen, A. (1999). Measuring attitudes regarding bisexuality in lesbian gay male and heterosexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(3), 353–369.

Morgan, B. (1996). Putting the feminism into feminism scales. Introduction of a liberal feminist attitude and ideology scale (LFAIS). Sex Roles, 34, 359–390.

Nagoshi, J., Adams, K., Terrell, H., Hill, E., Brzuzy, S., & Nagoshi, C. (2008). Gender differences in correlates of homophobia and transphobia. Sex Roles, 59, 521–531.

Norton, A., & Herek, G. (2013). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward transgender people: findings from a national probability sample of U.S. adults. Sex Roles, 68, 738–753.

Npr.com. (2008). Oklahoma: the reddest state December 6 2008. Available at: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId = 97905041

Ojerholm, A., & Rothblum, E. (1999). The relationships of body image, feminism, and sexual orientation in college women. Feminism & Psychology, 9(4), 431–448.

Pichardo-Galán J., Molinuevo P., Rodríguez M., & Romero-López, M. (2007). Actitudes ante la diversidad sexual dela población adolescente de Coslada (Madrid) y San Bartolomé de Tirajana (Gran Canaria). Available at: http://www.ampgil.org/mm/file/estudis/estudiocoslada.pdf

Platero-Méndez, R. (2007). Love and the state: gay marriage in Spain. Feminist Legal Studies, 15, 3.

Popkin, S. (1994). The reasoning voter. Chicago: UC Press.

Povoledo, E. (2016, February 16). Italian lawmakers’ vote on same-sex civil unions stalls, New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/17/world/europe/italy-same-sex-civil-unions.html

Prunas, A., Clerici, C., Gentile, G., Muccino, E., Veneroni, L., & Zoja, R. (2015). Transphobic murders in Italy: an overview of homicides in Milan (Italy) in the past two decades (1993–2012). Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(16), 2872–2885.

Raja, S., & Stokes, J. P. (1998). Assessing attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: the Modern Homophobia Scale. Journal of Gay Lesbian and Bisexual Identity, 3, 113–134.

Rifelli, A. (1998). Psicologia e psicopatologia della sessualità. Bologna, Italy: Il Mulino.

Roy, R., Weibust, K., & Miller, C. (2007). Effects of stereotypes about feminists on feminist self-identification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 146–156.

Sanjuán, T., Callejón, F. & Méndez, C. (2008). Legal study on homophobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation in Spain FRALEX.

Sheng, J. (2012) Comparison of tuition costs of higher education around the world. Accessed from http://jimsheng.hubpages.com/hub/Comparison-of-cost-of-higher-education-around-the-world

Slenders, S., Sieben, I., & Verbakel, E. (2014). Tolerance towards homosexuality in Europe: population composition, economic affluence, religiosity, same-sex union legislation and HIV rates as explanations for country differences. International Sociology, 29(4), 348–367.

Smith, T., Son, J., & Kim, J. (2014). Public attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights across time and countries. The Williams Institute. Available at: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/international/public-attitudes-nov-2014/

Sotelo, M. (2000). Political tolerance among adolescents toward homosexuals in Spain. Journal of Homosexuality, 39(1), 95–105.

Steele, L. S., Ross, L. E., Dobinson, C., Veldhuizen, S., & Tinmouth, J. M. (2009). Women’s sexual orientation and health: results from a Canadian population-based survey. Women & Health, 49(5), 353–367.

Svallfors, S. (2006). The moral economy of class. CA: Stanford Press.

Taylor, V., & Rupp, L. (1993). Women’s culture and lesbian feminist activism: a reconsideration of cultural feminism. Signs, 19(1), 32–61.

Terry, J. (1999). An American obsession. Chicago: UC Press.

Turner, L., Whittle, S., & Combs, R. (2009). Transphobic hate crime in the European Union. http://www.ilga-europe.org/sites/default/files/transphobic_hate_crime_in_the_european_union_0.pdf

Tygart, C. (1999). Genetic causation attribution and public support of gay rights. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 12(3), 259–275.

Van de Meerendonk, B., & Scheepers, P. (2004). Denial of equal civil rights for lesbians and gay men in the Netherlands, 1980–1993. Journal of Homosexuality, 47(2), 63–80.

van den Akker, H., van der Ploeg, R., & Scheepers, P. (2013). Disapproval of homosexuality: comparative research on individual and national determinants of disapproval of homosexuality in 20 European countries. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(1), 64–86.

Wald, K., Owen, D., & Hill, S. (1988). Churches as political communities. American Journal of Political Science, 82, 531–548.

Welch, M., Leege, D., Wald, K., & Kellstedt, L. (1993). Are the sheep hearing the shepherds? Cue perceptions, congregational responses, and political communication processes. pp. 235–54 in Rediscovering the Religious Factor in American Politics, edited by Leege and Kellstedt. M.E. Sharpe.

Williams, R., & Wittig, M. (1997). “I’m not a feminist, but…”: factors contributing to the discrepancy between pro-feminist orientation and feminist social identity. Sex Roles, 37(11/12), 885–904.

World Values Survey. (2005), World values survey association. Aggregate File Producer: ASEP/JDS, Madrid. Available at www.worldvaluessurvey.org.