Abstract

Given the widespread availability of sexual information and content on the internet, together with the web’s corresponding appeal (e.g., anonymity, portability, and social networking), it is likely that many adolescents learn about sex online. However, the internet has rarely been considered in studies on teenagers’ sources of sexual information, and the literature has several limitations and gaps. This study aims mainly to examine the amount of sexual information that a sample of Spanish adolescents receives from the internet, along with its usefulness, differences by sex and developmental stage, and associations with sexual behavior. A total of 3809 secondary students aged 12 to 17 completed a written survey anonymously. According to the analyses, 68.4 % of the participants had received sexual information online. Boys and middle adolescents obtained more (and more useful) information. Receiving more sexual information online was associated with masturbation and engaging in non-coital and coital behavior, but not with age or condom use at first intercourse. Since the internet appears to be a promising, useful, and widely accessed source of sexual information among adolescents, professionals are encouraged to incorporate internet-based approaches into their sexual education interventions with this age group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a high volume and variety of sexual information and content on the internet. According to Döring (2009), the six major areas are as follows: pornography, sex shops, sex work, sex contacts, sexual subcultures, and sex education. Given this context, and the fact that adolescents are early and major users of the internet, it is likely that many of them will receive sexual information from this source. Indeed, according to a recent review of surveys/interviews with adolescents and content analysis of their questions and discussions on sexual health websites (Simon & Daneback, 2013), this age group seeks or engages with a range of sex-related topics online: HIV/AIDS/STIs, pregnancy, sex acts/behavior, contraception, information about the body, relationships/social issues, and sexual identity/orientation.

Thanks to the internet, therefore, teens have “unprecedented access” to sexual information “in a convenient and confidential way” (Gray & Klein, 2006, p. 519). In other words, the internet’s availability, ease of use, and perceived anonymity regarding sensitive topics (Simon & Daneback, 2013) allow adolescents to quickly find answers to their questions about sexuality without engaging in embarrassing discussions with parents, teachers, or even friends. Moreover, adolescents may value online information about the sexual experiences of their peers (e.g., stories submitted by counterparts, teen chats) or, if LGBT, the possibility of avoiding the stigma still associated with sexual identity issues (Kanuga & Rosenfeld, 2004).

Prevalence of Internet Use for Sexual Information Among Adolescents

In an early study with tenth grade students from New York, Borzekowski and Rickert (2001a) found that the internet was the second most frequently reported source of information about birth control and safe sex (31.6 %) surpassed only by friends (61.3 %), although it was not among the top most valuable sources. Fifteen years later, a growing but still small body of research also indicates that the internet is used by a sizable portion of young people to obtain information about sexuality or sexual health, e.g., 44 % in the USA (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2001), 51–82 % in China, Taiwan, and Vietnam (Lou et al., 2012), and 51 % in the UK (Powell, 2008).

In Spain, Lara and Heras (2008) found that nearly half of a sample of 13–17 year-old adolescents sometimes (16.4 %) or quite a lot/always (31.9 %) used the internet as a source of sexual information. Lower, but non-negligible, rates have subsequently been reported in other Spanish studies, as well as differences by sex, suggesting that a higher portion of boys obtain sexual information online than girls, 30.8 vs. 15 % (Varela & Paz, 2010), and 40.9 vs. 30.5 % (Grupo Daphne, 2009) respectively, in keeping with studies from other countries (Fundación Huesped & Unicef, 2012; Lou et al., 2012). Other findings, however, suggest that females are more likely than males to obtain sexual health information online (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2001) or report that there are no differences between the sexes (Borzekowski & Rickert, 2001a). With regard to other sociodemographic factors, in a sample of Argentinean adolescents aged 14 to 19, the Fundación Huesped & Unicef (2012) found that the percentage using the internet as the primary source of sexual health information increased with age.

It is worth mentioning at this point that none of abovementioned studies suggests that the internet is the first source of information about sexuality among young people. On the contrary, research evidence from both Spain (Chas, Dieguez, Diz, & Sueiro, 2003; Gascón et al., 2003; Grupo Daphne, 2009; Lara & Heras, 2008; Robledo et al., 2007) and other countries (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2009; Fundación Huesped & Unicef, 2012; Matziou et al., 2009; Ruiz-Canela, López-del Burgo, Carlos, Calatrava, & Osorio, 2012; Secor-Turner, Sieving, Eisenberg, & Skay, 2011) indicates that adolescents’ sexual information is obtained mainly from friends, parents, school, and the media, in varying order. Nonetheless, many authors have not explicitly included the internet in the list of possible sources of information (e.g., Bleakley et al., 2009; Chas et al., 2003; Matziou et al., 2009; Robledo et al., 2007; Somers & Surmann, 2005), thus raising the question of whether respondents include it under the non-specific categories of “media” or “other sources.” Moreover, the available data on the prevalence of internet use for sexual information may be out of date and may not reflect the current situation since internet use is constantly increasing—and changing its patterns—among the adolescent population.

Associations with Adolescents’ Sexual Behavior

As mentioned above, owing to its accessibility and anonymity, among other advantages, the internet is an attractive source of sexual information for adolescents. For several reasons, however, this technology also raises concerns about its potential risks.

First, some authors have linked adolescent sexual behavior and/or outcomes with exposure to sex in other media (Collins et al. 2011a). For example, a longitudinal study of a sample of American early adolescents found that high exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicted pre-coital sexual activity and sexual intercourse 2 years later (Brown et al., 2006).

Additionally, concerns have grown due to the cross-cultural evidence that around 4 in 10 adolescents are exposed to pornography online (González & Orgaz, 2013; Livingstone & Haddon, 2009; Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2007), and the fact that higher exposure to internet pornography has been correlated with sexual experimentation (e.g., Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009; Brown & L’Engle, 2009), suggesting that adolescents may learn sexual behaviors from observing sexually explicit material online (Owens, Behun, Manning, & Reid, 2012).

Lo and Wei (2005), for example, found that more frequent exposure to internet pornography among Taiwanese adolescents predicted more frequent engagement in sexual behavior (holding hands, kissing, “love touching,” and/or sexual intercourse), even after controlling for the influence of sex, age, and religion. Inconsistently, however, a recent study of American adolescents showed that higher exposure to sexual material through the internet (people kissing, fondling, or having sex) failed to predict either having had sexual intercourse or age at first intercourse, after adjusting for other possibly influential factors such as sex and age (Ybarra, Strasburger, & Mitchell, 2014).

Concerning risky sexual behavior, the findings are also contradictory, some authors reporting that male adolescents exposed to online pornography are less likely to have used a condom during the previous intercourse (Luder et al., 2011), while others find no association between exposure to sexual content on the internet and condom use (Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009; Peter & Valkenburg, 2011; Ybarra et al., 2014).

It should be noted, nonetheless, that the above-cited literature refers only to one of the many types of sexual information that can be obtained online by adolescents: pornography or sexually explicit material. To the authors’ knowledge, only a few studies have examined whether receiving sexual information from the internet—in a variety of topics—is in any way associated with adolescents’ sexual behavior. Specifically, Lou et al. (2012) found that online access to more issues concerning sexual information (AIDS/STDs, sex, pregnancy, and/or contraception) among adolescents in Shanghai and Hanoi predicted higher levels of sex-related behavior, regardless of their sex. Similarly, Ruiz-Canela et al. (2012) observed in El Salvador that the percentage of sexually experienced adolescents was higher among those who usually resorted to “magazines/internet” for sexual information, as compared to those who did not.

In addition to the cases already described, current evidence has several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, studies examining whether teenagers obtain online information about sexuality—not only involving exposure to internet pornography—have placed their focus on sexual health subjects such as AIDS/STDs and contraception (e.g., Fundación Huesped & Unicef, 2012; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2001; Lou et al., 2012), thus ignoring other matters that may be of interest to them (e.g., sexual orientation, sexual values, affectivity, etc.). Moreover, only a few researchers (Borzekowski & Rickert, 2001a; Jones & Biddlecom, 2011) have analyzed teens’ opinions about the sexual information they receive online (e.g., whether it is valuable or useful).

Furthermore, most studies on young people’s sources of sexual information have collected samples from a single city (e.g., Borzekowski & Rickert, 2001a; Lara & Heras, 2008; Powell, 2008; Varela & Paz, 2010) and/or across a wide age range, such as 13–21 (Borzekowski & Rickert, 2001b; Varela & Paz, 2010), 12–19 (Powell, 2008), and 15–24 (Grupo Daphne, 2009; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2001; Lou et al., 2012) without differentiating the results by age or developmental stage, despite the probable relevance of these variables. Also, in some cases, not even the participants’ sex has been taken into account when analyzing the data (e.g., Lara & Heras, 2008; Powell, 2008).

Finally, evidence is lacking about whether receiving sexual information from the internet—on topics other than pornography—is associated with sexual behavior among adolescents. Available studies (Lou et al., 2012; Ruiz-Canela et al. 2012) have considered only interpersonal sexual behaviors (ignoring solitary ones such as masturbation) and do not provide data on whether condom use and age at first intercourse are associated factors, as do studies on adolescents’ exposure to internet pornography. Likewise, little is known about the moderating role that sex and age may play on the above associations.

In sum, the literature is still insufficient and far from conclusive, both in Spain and in other countries, since it provides little or no evidence of the amount of sexual information that teens receive online on topics other than pornography or sexual health, the perceived usefulness of this information, its relation to sexual behavior, and the impact that sex and age have on the findings. Additionally, there is a need for more up-to-date data and larger samples that exclude young adults—who are likely to differ in their internet use, their searches for sexual information, and their sexual behavior—and include early adolescents instead, who are digital natives but rarely recruited by researchers.

Given these limitations, the main purpose of this study is to examine the use of the internet as a source of sexual information in a sample of Spanish adolescents and its association with sexual behavior. Specifically, the first aim is to analyze the amount and usefulness of the sexual information on diverse topics received from the internet, as compared to other sources, while identifying differences by sex and developmental stage. The second aim is to examine whether the amount of sexual information received online is associated with sexual behavior among adolescents of both sexes and at different developmental stages. To the authors’ knowledge, no study has yet examined these issues in Spain.

Based on the above literature, it is first hypothesized that most participants, especially boys and middle adolescents, receive sexual information from the internet, albeit to a lesser extent than from friends, at school, parents, and the media. Second, it is predicted that regardless of sex and developmental stage, and after controlling for sociodemographic effects, receiving more sexual information online is associated with having masturbated and engaged in non-coital and coital behavior, but is not related to age or condom use at first intercourse.

Method

Participants

The sample consists of 3809 adolescents, 49.4 % boys and 50.6 % girls. At the time of data collection (Spring semester 2012), the participants’ mean age was 14 (M = 14.36; SD = 1.37), 52.4 % being early adolescents (12–14), and 47.6 % being middle adolescents (15–17). All of them were secondary school students (22.7 % in the first year, 20.9 % in the second, 31.2 % in the third, and 25.1 % in the fourth) attending 26 high schools—25 of them public—in seven of the nine provinces that make up the Autonomous Community of Castilla y Leon, in Spain. Overall, 53 % of participants attended a rural high school, and the rest an urban one.

According to the available data (Regional Government of Castilla y Leon, 2013), the sample represents 4.5 % of the region’s population of adolescents aged 12–17 that were enrolled in secondary school during 2011–2012 (N = 85,509). The sample distribution by sex and age is similar to that of the above-cited population.

Variables and Instruments

The variables of interest in this study were assessed through a self-administered survey that included diverse instruments, as described below:

Sociodemographic Variables

Two questions asked participants about their sex (male or female) and age. The developmental stage was obtained by recoding age in two categories, early adolescence (12–14) and middle adolescence (15–17), in accordance with the classification by Dixon-Mueller (2008). In addition, school location was obtained by categorizing the participants’ school (information registered by data collectors) as rural or urban.

Amount of Sexual Information Received from a Source

A self-designed instrument based on Somers et al. (Somers & Gleason, 2001; Somers & Surmann, 2005) presented the participants with seven items indicating seven topics commonly included in Spanish school-based sex education programs for adolescents, as well as examples of each topic. These items were as follows: sexual anatomy/physiology (e.g., genitals, menstruation, puberty, pregnancy, and abortion), sexual behaviors/human sexual response (e.g., masturbation, coitus, sexual arousal, and orgasm), sexual health (e.g., contraception, STIs, AIDS, and sexual abuse), affectivity (e.g., love, falling in love, romantic relationships, and intimacy), sexual orientation/gender identity (e.g., homo/hetero/bisexual and transgender), sexuality in society (e.g., sexual violence, sex work, pornography, eroticism, sexual legislation, and sex roles), and sexual values (e.g., whether to engage in sexual acts, when, with whom, and what is right or wrong in sexuality).

Participants were asked to rate how much information they had received about each topic from the internet, as well as from other sources (father, mother, siblings, friends, school, books, and TV/media) on a five-point Likert-type scale (0 = none at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = a moderate amount, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = a lot).

Usefulness of the Sexual Information Received from a Source

Participants were asked to rate how useful the sexual information provided by the internet and by the other above sources had been to them on a five-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much).

Sexual Behavior Variables

Participants were asked whether they had ever masturbated (masturbatory experience) and/or engaged in each one of the following four sexual behaviors: kissing, fondling of genitals/breasts over clothing, fondling of genitals/breasts under clothing, and genital contact (non-coital experience). The latter was coded as a dichotomous variable (no experience vs. experience in at least two of the four behaviors) to facilitate the analysis. Furthermore, respondents were asked whether they had ever had sexual intercourse (coital experience), and if so, whether they had used a condom during their first intercourse experience (condom use at first intercourse) and how old they were at that time (age at first intercourse). In all cases, with the exception of this last variable, the response options were either “yes” or “no.”

Procedure

A convenience sampling procedure was used to select adolescents from Castilla y Leon (Spain). All the high school principals contacted were informed about the study via e-mail and telephone. They were also sent a copy of the survey and an introductory letter to be used to inform both students and parents about the study. In order to ensure ethical treatment of the participants, the letter explained that: (a) participation was voluntary and anonymous, (b) responses would be used solely for research purposes, (c) the survey included questions on sexual information sources and sexual behavior among other sexuality variables, (d) participants could leave any question unanswered or drop out of the survey, and (e) both students and parents could contact researchers for further information. Moreover, the letter requested parents to provide written consent for the student’s participation.

From among the 56 high schools contacted (48 public, 8 private; 24 rural, 32 urban), 18 (32.1 %) rejected collaboration (11 public, 7 private; 3 rural, 15 urban) because of time constraints, the perceived tediousness of completing surveys, or concern about parents’ likely reactions. Participants were recruited at the schools that first accepted the invitation to collaborate.

Written self-administered surveys were conducted in the classrooms. The students were reminded that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and the survey took around 40 min to complete. Only those students that agreed to participate and whose parents had provided consent completed the survey forms, while the rest did their school assignments (only a few students who were willing to participate were not allowed to do so by their parents). Classroom desks were separated in order to preserve privacy.

Analyses

In order to test the first set of hypotheses, descriptive analyses were performed to examine the amount of sexual information received from the different sources (both overall and regarding each topic) as well as its usefulness.Footnote 1 One-way repeated measures ANOVAs (with eight groups corresponding to the eight sources) and Bonferroni post hoc tests were conducted to find significant differences between the sources. Significant differences by sex and developmental stage in the amount and usefulness of the sexual information received online were identified with independent sample t tests.

In order to test the second set of hypotheses, and based on the methodology of similar studies (Lo & Wei, 2005; Lou et al., 2012; Ybarra et al., 2014), ten hierarchical regression analyses were performed.

First, five hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to assess whether the amount of sexual information received from the internet was associated with the five sexual behavior variables among participants of both sexes and the two developmental stages (i.e., regardless of whether they were male/female and early/middle adolescents), after controlling for school location. The rationale for these analyses was to determine whether sex and developmental stage played a moderating role in the above associations (since evidence is lacking), while at the same time accounting for possible school effects. School location was included in a first step as a control variable. Sex, developmental stage, and the amount of sexual information from the internet were entered as main effects in a second step. Finally, two 2-way interactions (amount of sexual information from the internet × sex, amount of sexual information from the internet × developmental stage) were added in a third step to test what they added to the prediction of sexual behavior.

Secondly, five hierarchical regression analyses were performed to assess whether the amount of sexual information received online was associated with the five sexual behavior variables, after controlling for sociodemographics; that is, after the possible overlapping effects of school location, sex, and developmental stage were removed since the latter variables have in fact been related to adolescents’ sexual behavior (e.g., Bermúdez, Buela-Casal, & Teva, 2011). The three sociodemographic variables were included in a first step as control variables, and the amount of sexual information from the internet was entered in a second step to test what it added to the prediction of sexual behavior.

In this study, age at first intercourse and both the amount and usefulness of the sexual information received from a source were used as continuous variables, while the rest were used as dichotomous variables. Consequently, both logistic and linear regression analyses were conducted, depending on whether the outcome variable was dichotomous (masturbatory experience, non-coital experience, coital experience, and condom use at first intercourse) or continuous (age at first intercourse), respectively.Footnote 2 The footnote to Table 3 explains how the variables were coded for analysis.

All the analyses were conducted with SPSS-20. The level of significance was set at .01, and effect sizes were calculated from ANOVAs and t tests because of the large size of the sample.

Results

Overall, 68.4 % of the participants reported having received some kind of sexual information from the internet (since the mean amount of information they obtained online about the seven sexual topics was different from 0), being broken down as follows: 78.1 % of boys and 59.2 % of girls, 60.1 % of early adolescents, and 77.5 % of middle adolescents.

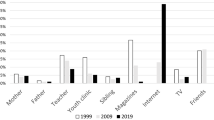

In overall terms, the ANOVA results indicate significant differences in the amount of sexual information received by participants from the various sources [F (7, 25,508) = 814.74, p < .001, eta squared = .18]. According to the Bonferroni test, there were significant differences between the overall scores (p < .01), with the exception of TV/media and the mother. Specifically, as shown in Table 1, the sources that provided the most sexual information were friends, school, TV/media, and the mother, in that order. The internet lay fifth in the ranking with, on average, “a little bit” of information (M = 1.22, SD = 1.2), which was more than that obtained from the father, books, and siblings.

Similarly, the ANOVA results indicated significant differences (p < .001) in the amount of information provided by the various sources about each sexual topic. In all cases, however, the Bonferroni test revealed that the amount of information received from the internet was not significantly different (p > .01) from that obtained from other sources (see Table 1). Taking this into account, the internet was the second source providing participants with the most information on sexual behavior/human sexual response and the third in providing the most information on sexual anatomy/physiology, sexual health, affectivity, and sexuality in society.

Moreover, the sources that provided participants with the most useful sexual information were friends (M = 2.50, SD = 1.3) and the mother (M = 2.16, SD = 1.3). In this case, the internet lay third in the ranking, and its sexual information was also seen, on average, as “moderately” useful (M = 2.02, SD = 1.5), whereas that provided by all the other sources was considered “a little bit” useful (school: M = 1.94, SD = 1.3; siblings: M = 1.87, SD = 1.4; father: M = 1.83, SD = 1.4; TV/media: M = 1.73, SD = 1.3; books: M = 1.37, SD = 1.2).

With regard to sex differences, the boys received significantly more sexual information online (M = 1.47, SD = 1.30) than did the girls (M = 0.96, SD = 1.16), both in overall terms [t (3533.398) = 12.44, p < .001, eta squared = .041] and regarding each sexual topic (p < .001). In fact, the internet was third in the list of sources providing males with the most sexual information, whereas it was in fifth position for females (see Table 2).

Similarly, boys considered the sexual information obtained online to be significantly more useful (M = 1.75, SD = 1.62) than did girls (M = 1.12, SD = 1.37) [t (3272.533) = 12.31, p < .001, eta squared = .042]. As shown in Table 2, the internet was the second source providing males with the most useful sexual information, whereas it was in fifth position for females.

With respect to the differences by developmental stage, middle adolescents obtained significantly more sexual information from the internet (M = 1.43, SD = 1.26) than early adolescents (M = 1.00, SD = 1.20), both in overall terms [t (3509.77) = −10.381, p < .001, eta squared = .029] and regarding each sexual topic (p < .001). Likewise, older adolescents regarded such information as significantly more useful (M = 1.62, SD = 1.51) than their younger counterparts (M = 1.24, SD = 1.52) [t (3412) = −7.354, p < .001, eta squared = .015]. In all cases, however, the effect sizes were small.

Finally, according to the first set of hierarchical regression analyses, neither sex nor developmental stage played a moderating role in the association between the amount of sexual information received from the internet and each of the five sexual behavior variables since all the interactions assessed were non-significant (p > .05).

According to the second set of hierarchical regression analyses (see Table 3), receiving more sexual information online was significantly associated with having masturbated and engaged in non-coital and coital behavior (p < .001), even after controlling for sociodemographics. However, it added a higher percentage of variance to the prediction of non-coital (R 2 c = .055) and masturbatory (R 2 c = .043) experience than to the prediction of coital experience (R 2 c = .013). Neither condom use nor age at first intercourse was associated with the amount of sexual information received online (p > .05).

Discussion

As expected, most of the participants in this study (68.4 %) had at some time used the internet as a source of information about sexuality. This prevalence rate is higher than others encountered both in previous Spanish studies (e.g., Grupo Daphne, 2009; Lara & Heras, 2008) and in international surveys (e.g., Lou et al., 2012; Powell, 2008). This may, to some extent, be due to the fact that internet use has soared worldwide in recent years (Internet live stats, 2014). It should be noted, however, that when this study was conducted, the internet use rate of Spanish adolescents—over 90 % (National Office of Statistics - INE 2013)—was much higher than the rate quoted above. Apparently, therefore, there is a significant portion of teen internet users in SpainFootnote 3 who have not accessed online sexual information; this may be, as some qualitative data suggest (Scarcelli, 2014), because they believe that this information is unreliable and/or mainly consists of pornography.

Beyond prevalence rates, and consistent both with previous findings (Lara & Heras, 2008; Secor-Turner et al., 2011) and our own hypothesis, the results of this study indicate that the internet is not currently the first source of sexual information among the adolescents studied. According to the participants, however, on average, all the sources assessed here provide only “a little bit” of sexual information, possibly because they feel they are still far from receiving the amount of information they expect or wish to obtain from the various socialization agents, including the internet. Furthermore, from the participants’ viewpoint, the sexual information provided by the internet is the third most useful—only surpassed by that provided by friends and mothers, which may be deemed more trustworthy— perhaps because it better meets adolescents’ needs and interests or it answers sensitive questions easily and anonymously that would otherwise elicit embarrassing discussions or are addressed with less detail or explicitness by teachers, books, the TV, etc.

In this study, the three sexual topics about which the internet provides most information for adolescents are sexual anatomy/physiology, sexual behaviors/human sexual response, and sexuality in society (e.g., genitals, masturbation, coitus, orgasm, sex work, and pornography). Thus, in keeping with the review by Simon & Daneback (2013), it appears that adolescents want to learn about more than just sexual health from the internet, although it remains unclear whether these are the issues they are most interested in and/or the ones most readily accessible online.

With regard to differences by sex, and in line with previous studies (Grupo Daphne, 2009; Lou et al., 2012; Varela & Paz, 2010), the use of the internet as a source of sexual information is more prevalent among the male adolescents in the sample, as compared to their female counterparts. Here, in fact, boys obtain more (and more useful) sexual information online than girls do to the extent that they look upon the internet as the second source in terms of providing the most information and the third one as regards the most useful information. This may be because boys use this tool more intensively (Carbonell et al., 2012) or because they especially appreciate the possibility that it offers of anonymously satisfying their curiosity, thus avoiding embarrassing face-to-face questions or a public image of “ignorance” regarding an issue that boys are expected to be knowledgeable about.

Likewise, and also as predicted, the internet seems to be more commonly and intensively used to obtain sexual information by middle adolescent participants than by early adolescent ones, which is congruent with previous evidence indicating that exposure to online pornography is more prevalent among older adolescents (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011). This can probably be explained to some extent by the fact that sexual contacts among Spanish adolescents increase with age (Bermúdez et al., 2011), as does internet use (National Office of Statistics - INE 2013). Another possible influencing factor is that the parents of older adolescents are less likely to use control systems to prevent them from accessing sexual content online.

Also, and similarly to other studies (Lou et al., 2012; Ruiz-Canela et al., 2012), it was observed here that adolescents who obtain more sexual information from the internet are significantly more sexually experienced, irrespective of their sex and developmental stage (early vs. middle adolescence), even after accounting for the overlapping influence of these variables. Based on prior findings concerning adolescents’ exposure to sex in the media (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2008), it is likely that the observed association is bidirectional; that is, obtaining more sexual information online (about sexual practices, sexual anatomy, etc.) encourages sexual experimentation, and likewise, being sexually experienced fosters the search for sexual information on the internet. Remarkably, not only interpersonal sexual behavior (especially non-coital) but also masturbation appears to be related, perhaps because a good deal of online sexual content is sought out by adolescents for sexual self-stimulation or provokes sexual arousal when encountered accidentally.

It should be noted, however, that the above associations are not strong since the amount of sexual information received online accounted for 5.5 %, at the most, of the variance in sexual behavior in this study. Moreover, as in earlier studies addressing adolescents’ exposure to online pornography (Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009; Ybarra et al., 2014), receiving sexual information from the internet has not been associated with condom use nor age at first intercourse among participants (both variables proved to be more closely related to the developmental stage), thus questioning whether concerns about the risks this information poses are sufficiently substantiated.

This study has certain limitations that are worth noting. First, it has used a convenience sampling procedure to select secondary students from the Spanish Autonomous Community of Castilla y Leon, most of them enrolled in public high schools and whose parents consented to their participation. Therefore, the findings may not be representative of all secondary students in Spain, nor of students at private schools, those who were not authorized or willing to participate, or adolescents not in education. Further, this study did not assess internet access or usage parameters (frequency, purposes, etc.), thus hindering the analysis of associations between these variables and reports on the amount of sexual information received online. Finally, the correlational nature of the findings does not allow the direction of influences to be determined (whether the amount of online sexual information received has an impact on sexual behavior, or vice versa), which limits the understanding of the associations encountered between variables. Despite its limitations, this study contributes to the literature addressing the field insofar that, based on a large sample of early and middle adolescents, it is the first that examines the amount of sexual information received online concerning a broad variety of topics, in comparison with that obtained from traditional sources, while at the same time it analyzes associations with sexual behavior and considers the influence of sex and age on the results.

Future research could thus benefit from using longitudinal designs that better test causal effects. Further, qualitative studies are also recommended for gaining an understanding of adolescents’ views and experiences regarding their use of the internet as a source of sexual information (e.g., whether they deliberately or involuntary access sexual information online, what they seek, why and how they seek it, what they find, and why it is useful or of little use). In this regard, some existing instruments developed to assess college students’ perceptions and behavior when searching for sex-related information on the internet (Goodson, McCormick, & Evans, 2000) may serve as a reference, as may the qualitative studies conducted in this area (e.g., Buhi, Daley, Fuhrmann, & Smith, 2009; Daneback, & Löfberg, 2011; Jones & Biddlecom, 2011). Moreover, scholars are advised to consider the role that the latest devices (e.g., smartphones and tablets) and widely used social networks, instant messaging, and video-sharing websites (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp, and YouTube) may play in teenagers’ access to online sexual information.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence to suggest that the internet is a useful and widely used source of sexual information among adolescents in Spain, especially among males and middle adolescents, that has not, at least yet, replaced traditional sources of sexual information (family, school, friends, and the media), but instead has supplemented them. Consequently, from the perspective of social and public policy, the authors recommend that Spanish regional and national ministries for social, educational, and health issues should carry out two essential measures.

The first is to consider the use of online sexual information as a relevant objective and issue in sex education interventions. In other words, adolescents should be taught how to think critically about the sexual information they access on the internet and how to use search strategies to find reliable and comprehensive websites. These skills would help them access high-quality sexual information, while at the same time preventing risks (e.g., harmful materials, sexting, and grooming).

The second measure is to use the internet as a relevant medium to provide adolescents with sexual information. Namely, professionals should be encouraged to incorporate internet-based approaches into their sex education interventions (Allison et al., 2012; Barak & Fisher, 2001), thereby taking advantage of this technology’s services (e.g., social networks, instant messaging, and podcasts), capabilities (e.g., interactivity, portability, privacy, multimedia communication, and data collection), and appeal to teenagers. Some interesting experiences have already been implemented with relative success (e.g., Marsch et al. 2011; Lou, Zhao, Gao, & Shah, 2006). Moreover, the Spanish public administration should foster and supervise the creation of websites and Smart Phone apps on sexuality issues to be used not only by adolescents but also their parents and teachers as well (because of their responsibility in sex education). It is advised that these resources: (a) be developed by health/education/social professionals with the collaboration of technology experts and adolescents; (b) should include relevant, trustworthy, and age/content-appropriate information on a broad variety of sexual topics, aside from sexual health; (c) be widely disseminated among high schools, websites/TV programs relevant to adolescents, parents’ associations, universities, etc.; and (d) should encourage teens to share reliable sexual knowledge with friends (e.g., via social networks and online quizzes) in order to take advantage of the source they use the most. Likewise, it would be advisable to evaluate the impact of internet-based interventions on adolescents’ sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in order to guide improvements (Collins et al. 2011b; Guse et al., 2012).

Hopefully, the above measures would help adolescents to make safe and profitable use of this promising tool for sexual information purposes.

Notes

Overall scores were obtained by calculating the mean amount of information received about the diverse topics. Only responses provided by participants with siblings were considered when examining the amount of information received from that source. Analyses on the usefulness of the information were carried out solely for those participants that reported having received information from a source.

Regression analyses of condom use at first intercourse and age at first intercourse were conducted solely for those participants who reported having had coital experience.

Throughout the “Discussion,” the terms “Spain/Spanish” are used generically to refer to this cohort from the Autonomous Community of Castilla y Leon due to the international nature of the journal. It is not the authors’ intention to overstate the results. Given the sample characteristics and sampling procedure used, the findings could be generalized with caution to secondary students attending public schools in the Autonomous Community of Castilla y Leon. To the authors’ knowledge, however, no evidence nor socio-cultural factor suggests that secondary students attending public schools in other Spanish Autonomous Communities may differ significantly in the variables assessed, e.g., some data indicate that the age of Spanish adolescents at the onset of sexual activity does not differ from one Autonomous Community to another (Teva, Bermúdez, & Buela-Casal, 2009)

References

Allison, S., Bauermeister, J. A., Bull, S., Lightfoot, M., Mustanski, B., Shegog, R., et al. (2012). The intersection of youth, technology, and new media with sexual health: moving the research agenda forward. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(3), 207–212.

Barak, A., & Fisher, W. A. (2001). Toward and internet-driven, theoretically-based, innovative approach to sex education. The Journal of Sex Research, 38(4), 324–332.

Bermúdez, M. P., Buela-Casal, G., & Teva, I. (2011). Type of sexual contact and precoital sexual experience in Spanish adolescents. Universitas Psychologica, 10(2), 411–421.

Bleakley, A., Hennessy, M., Fishbein, J., & Jordan, A. (2008). It works both ways: the relationship between exposure to sexual content in the media and adolescent sexual behavior. Media Psychology, 11(4), 443–461.

Bleakley, A., Hennessy, M., Fishbein, M., & Jordan, A. (2009). How sources of sexual information relate to adolescents’ beliefs about sex. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(1), 37–48.

Borzekowski, D. L., & Rickert, V. I. (2001a). Adolescent cybersurfing for health information: a new resource that crosses barriers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155, 813–817.

Borzekowski, D. L., & Rickert, V. I. (2001b). Adolescents, the internet, and health: issues of access and content. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 22(1), 49–59.

Braun-Courville, D. K., & Rojas, M. (2009). Exposure to sexually explicit web sites and adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 156–162.

Brown, J. D., & L’Engle, K. L. (2009). X-rated: sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with U.S. Early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Communication Research, 36, 129–151.

Brown, J. D., L’Engle, K. L., Pardun, C. J., Guo, G., Kenneavy, K., & Jackson, C. (2006). Sexual media matter: exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts black and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics, 117(4), 1018–1027.

Buhi, E. R., Daley, E. M., Fuhrmann, H. J., & Smith, S. A. (2009). An observational study of how young people search for online sexual health information. Journal of American College Health, 58(2), 101–111.

Carbonell, X., Chamarro, A., Griffiths, M., Oberst, U., Cladellas, R., & Talarn, A. (2012). Problematic Internet and cell phone use in Spanish teenagers and young students. Anales de Psicología, 28, 789–796.

Chas, M. D., Diéguez, J. L., Diz, M. C., & Sueiro, E. (2003). Fuentes de información y conocimientos sexuales de riesgo en adolescentes residentes en el medio rural gallego (1ª Parte). Cuadernos de Medicina Psicosomática y Psiquiatría de Enlace, 65, 41–54.

Collins, R. L., Martino, S. C., Elliot, M. N., & Miu, A. (2011a). Relationships between adolescent sexual outcomes and exposure to sex in media: robustness to propensity-based analysis. Developmental Psychology, 47(2), 585–591.

Collins, R. L., Martino, S. C., & Shaw, R. (2011b). Influence of new media on adolescent sexual health: evidence and opportunities (working paper). Washington, DC: Rand Health.

Daneback, K., & Löfberg, C. (2011). Youth, sexuality and the internet: young people’s use of the internet to learn about sexuality. In E. Dunkels, G. M. Franberg, & C. Hällgren (Eds.), Youth culture and net culture: online social practices (pp. 190–206). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Dixon-Mueller, R. (2008). How young is “too young”? Comparative perspectives on adolescent sexual, marital, and reproductive transitions. Studies in Family Planning, 39(4), 247–262.

Döring, N. M. (2009). The Internet’s impact on sexuality: a critical review of 15 years of research. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1089–1101.

Fundación Huesped y Unicef (2012). Conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas en VIH y salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) y uso de tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) entre adolescentes de Argentina. Argentina: Fundación Huesped y Unicef.

Gascón, J. A., Navarro, B., Gascón, F. J., Pérula, L. A., Jurado, A., & Montes, G. (2003). Sexualidad y fuentes de información en población escolar adolescente. Medicina de Familia, 4(2), 124–129.

González, E., & Orgaz, B. (2013). Minors’ exposure to online pornography in Spain: Prevalence, motivations, contents and effects. Anales de Psicología, 29(2), 319–327.

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2000). Sex and the internet: a survey instrument to assess college students’ behavior and attitudes. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3(2), 129–149.

Gray, N. J., & Klein, J. D. (2006). Adolescents and the internet: health and sexuality information. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 18(5), 519–524.

Grupo Daphne. (2009). 3ª encuesta Bayer Schering Pharma: sexualidad y anticoncepción en la juventud española. Madrid: Bayer Schering Pharma.

Guse, K., Levine, D., Martins, S., Lira, A., Gaarde, J., Westmorland, W., et al. (2012). Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: a systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(6), 535–43.

Internet live stats (2014). Internet users in the world. Retrieved February 15, 2015, from: http://www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users/#trend.

Jones, R. K., & Biddlecom, A. E. (2011). Is the internet filling the sexual health information gap for teens? An exploratory study. Journal of Health Communication, 16(2), 112–123.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2001). Generation RX.com: how young people use the internet for health information: a Kaiser Family Foundation Survey. Menlo Park, CA: The Foundation.

Kanuga, M., & Rosenfeld, W. D. (2004). Adolescent sexuality and the internet: the good, the bad, and the URL. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 17(2), 117–124.

Lara, F., & Heras, D. (2008). Formación sobre sexualidad en la primera etapa de la adolescencia. Datos obtenidos en una muestra de 2° y 3° de ESO en burgos. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 241–248.

Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2009). EU Kids online. Final report. London, UK: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children. Full findings. LSE, London: EU Kids Online.

Lo, W., & Wei, R. (2005). Exposure to internet pornography and Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49(2), 221–237.

Lou, C., Zhao, Q., Gao, E., & Shah, I. (2006). Can the internet be used effectively to provide sex education to young people in China? Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 720–728.

Lou, C., Cheng, Y., Gao, E., Zuo, X., Emerson, M. R., & Zabin, L. S. (2012). Media's contribution to sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors for adolescents and young adults in three Asian cities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(3 Suppl), S26–36.

Luder, M. T., Pittet, I., Berchtold, A., Akré, C., Michaud, P. A., & Surís, J. C. (2011). Associations between online pornography and sexual behavior among adolescents: myth or reality? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 1027–1032.

Marsch, L. A., Grabinski, M. J., Bickel, W. K., Desrosiers, A., Guarino, H., Muehlbach, B., et al. (2011). Computer-assisted HIV prevention for youth with substance use disorders. Substance Use & Misuse, 46, 46–56.

Matziou, V., Perdikaris, P., Petsios, K., Gymnopoulou, E., Galanis, P., & Brokalaki, H. (2009). Greek students’ knowledge and sources of information regarding sex education. International Nursing Review, 56, 354–360.

National Office of Statistics - INE (2013). Encuesta sobre Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2015 from: http://www.ine.es/jaxi/menu.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t25/p450/base_2011/a2013/&file=pcaxis

Owens, E. W., Behun, R. J., Manning, J. C., & Reid, R. C. (2012). The impact of internet pornography on adolescents: a review of the re-search. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19, 99–122.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2011). The influence of sexually explicit Internet material on sexual risk behavior: a comparison of adolescents and adults. Journal of Health Communication, 16(7), 750–767.

Powell, E. (2008). Young people's use of friends and family for sex and relationships information and advice. Sex Education, 8(3), 289–302.

Regional Government of Castilla y Leon (2013). Estadística de la enseñanza no universitaria. Tabla de datos estadísticos, curso 2011–2012 (ESO: Alumnado matriculados por edad y sexo). Retrieved February 15, 2015, from: http://www.educa.jcyl.es/es/informacion/estadistica-ensenanza-universitaria/curso-2011-2012

Robledo, A., López, A., de Jaén, S., Sánchez, R., del Río, L., & Barrera, E. (2007). Conocimientos y comportamientos sexuales de los adolescentes escolarizados de Parla. Sexología Integral, 4(2), 73–79.

Ruiz-Canela, M., López-del Burgo, C., Carlos, S., Calatrava, M., & Osorio, A. (2012). Familia, amigos y otras fuentes de información asociadas al inicio de las relaciones sexuales en adolescentes de El Salvador. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica, 31(1), 54–61.

Scarcelli, C. M. (2014). “One way or another I need to learn this stuff!” Adolescents, sexual information, and the Internet’s role between family, school, and peer groups. Interdisciplinary Journal of family studies, 19(1), 40–59.

Secor-Turner, M., Sieving, R. E., Eisenberg, M. E., & Skay, C. (2011). Associations between sexually experienced adolescents’ sources of information about sex and sexual risk outcomes. Sex Education, 11(4), 489–500.

Simon, L., & Daneback, K. (2013). Adolescents’ use of the internet for sex education: a thematic and critical review of the literature. International Journal of Sexual Health, 25(4), 305–319.

Somers, C. L., & Gleason, J. H. (2001). Does source of sex education predict adolescents’ sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors? Education, 121(4), 674–681.

Somers, C. L., & Surmann, A. T. (2005). Sources and timing of sex education: relations with American adolescent sexual attitudes and behavior. Educational Review, 57(1), 37–54.

Teva, I., Bermúdez, M. P., & Vuela-Casal, G. (2009). Variables sociodemográficas y conductas de riesgo en la infección por el VIH y las enfermedades de transmisión sexual en adolescentes. España, 2007. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 83(3), 309–320.

Varela, M., & Paz, J. (2010). Estudio sobre conocimientos y actitudes sexuales en adolescentes y jóvenes [sexual knowledge and attitudes in adolescents and young adults]. Revista Internacional de Andrología, 8(2), 74–80.

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). Unwanted and wanted exposure to online pornography in a national sample of youth internet users. Pediatrics, 119, 247–257.

Ybarra, M. L., Strasburger, V. C., & Mitchell, K. J. (2014). Sexual media exposure, sexual behavior and sexual violence victimization in adolescence. Clinical Pediatrics, 53(13), 1239–47.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Regional Ministry of Education of Castilla y Leon (Spain) for providing funding for this research work.

Funding

This study was funded by the Regional Ministry of Education of Castilla y Leon, in Spain (grant number SA081A11-1).

Compliance With Ethical Standards

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the General Directorate for Universities and Research of the Regional Ministry of Education of Castilla y Leon (Spain) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González-Ortega, E., Vicario-Molina, I., Martínez, J.L. et al. The Internet as a Source of Sexual Information in a Sample of Spanish Adolescents: Associations with Sexual Behavior. Sex Res Soc Policy 12, 290–300 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0196-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0196-7